Who Will Save the Savior? The Relationship between Therapists’ Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Stress Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care

1.2. Secondary Traumatic Stress

1.3. Secondary Traumatic Stress Efficacy

1.4. The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Attitudes Related to the TIC (ARTIC) Scale [20]

2.2.2. Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) Questionnaire [36]

2.2.3. Secondary Traumatic Self-Efficacy (STSE) Questionnaire [50]

2.2.4. Demographic and Professional Background of Therapists

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlational Analyses

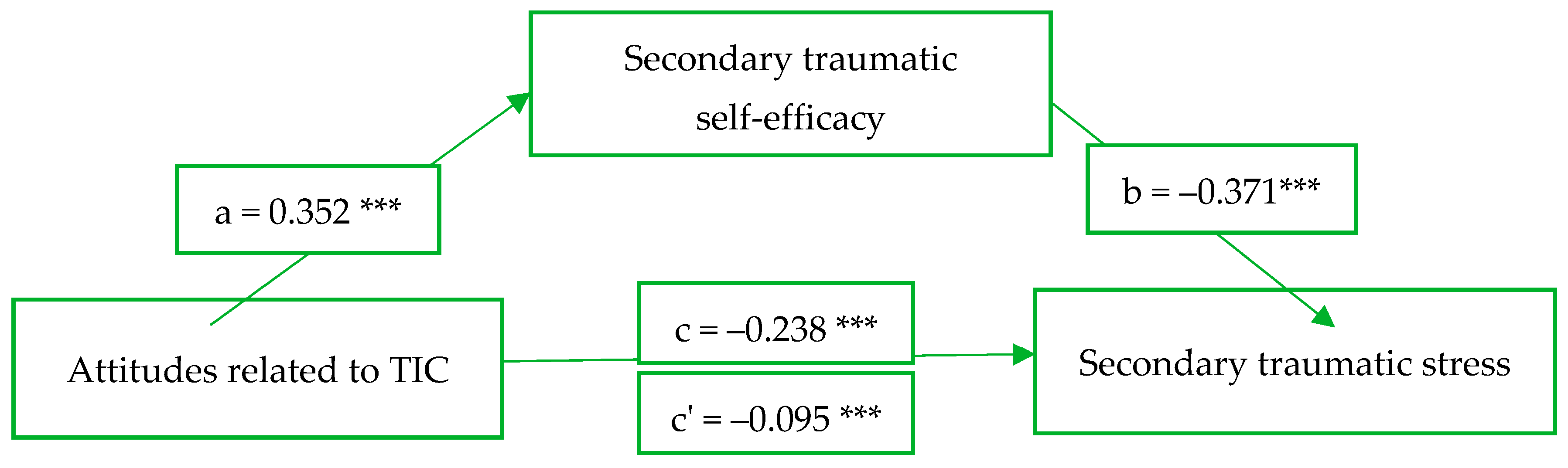

3.2. The Mediational Role of Therapists’ STSE in the Relationship between the Attitude toward TIC and STS (Total Score and Dimensions)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Children’s Bureau. Child maltreatment 2018. In Administration on Children, Youth and Families; Administration for Children and Families; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/cb/cm2018.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Bartlett, J.D. Trauma-informed practices in early childhood education. ZERO TO THREE J. 2021, 41, 24–34. [Google Scholar]

- De Young, A.C.; Kenardy, J.A.; Cobham, V.E. Trauma in early childhood: A neglected population. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2011, 14, 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, A.F. Traumatic stress and quality of attachment: Reality and internalization in disorders of infant mental health. Infant Ment. Health J. 2004, 25, 336–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J.D.; Griffin, J.L.; Spinazzola, J.; Goldman Fraser, J.; Noroña, C.R.; Bodian, R.; Todd, M.; Montagna, C.; Barto, B. The impact of a statewide trauma-informed care initiative in child welfare on the well-being of children and youth with complex trauma. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 84, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, M.; Hopp, D.; Tyano, S. Does Time Heal All? Exploring Mental Health in the First 3 Years; Trans, L.L., Ed.; ZERO TO THREE: Washington, DC, USA, 2017; (Original work published 2013). [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah, C.H.; Humphreys, K.L. Child abuse and neglect. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2018, 57, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ZERO TO THREE. DC:0–5™: Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders of Infancy and Early Childhood; ZERO TO THREE: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, R. Trauma-informed care for infant and early childhood abuse. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 389–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, A.F.; Van Horn, P. Psychotherapy with Infants and Young Children: Repairing the Effects of Stress and Trauma on Early Attachment; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van Horn, P.; Lieberman, A.F. Using dyadic therapies to treat traumatized young children. In Treating Traumatized Children: Risk, Resilience and Recovery; Brom, D., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Ford, J.D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2008; pp. 228–242. [Google Scholar]

- Garwood, M.M.; Beyer, M.R.; Hammel, J.; Schutz, T.; Paradis, H.A. Trauma-informed care intervention for culture and climate change within a child welfare agency. Child Welf. 2020, 98, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, S.; Gonzalez, R.; Tomlinson, P. Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Young People: An Attachment and Trauma-Informed Model for Practice [Kindle Edition]; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sprang, G.; Craig, C.; Clark, J. Secondary traumatic stress and burnout in child welfare staff: A comparative analysis of occupational distress across professional groups. Child Welf. 2011, 90, 149–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, J.D.; Barto, B.; Griffin, J.L.; Goldman Fraser, J.; Hodgdon, H.; Bodian, R. Trauma-informed care in the Massachusetts Child Trauma Project. Child Maltreatment 2016, 21, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, R.F.; Lang, J. A critical look at trauma-informed care among agencies and systems serving maltreated youth and their families. Child Maltreatment 2016, 21, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. (October 2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach (Publication No. SMA14-4884). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Policy, Planning and Innovation. Available online: https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Christian-Brandt, A.S.; Santacrose, D.E.; Barnett, M.L. In the trauma-informed care trenches: Teacher compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and intent to leave education within underserved elementary schools. Child Abus. Negl. 2020, 110, 104437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprang, G.; Garcia, A. An Investigation of Secondary Traumatic Stress and Trauma-informed Care Utilization in School Personnel. J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 2022, 15, 1095–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.N.; Brown, S.M.; Wilcox, P.D.; Overstreet, S.; Arora, P. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Attitudes Related to Trauma-Informed Care (ARTIC) Scale. Sch. Ment. Health 2016, 8, 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargeman, M.; Smith, S.; Wekerle, C. Trauma-informed care as a rights-based “standard of care”: A critical review. Child Abus. Negl. 2021, 119, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, E.; Probst, J.C.; Radcliff, E.; Bennett, K.J.; McKinney, S.H. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among US children. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 92, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarons, G.A. Measuring provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice: Consideration of organizational context and individual differences. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 14, 225–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.M.; Baker, C.N.; Wilcox, P. Risking connection trauma training: A pathway toward trauma-informed care in child congregate care settings. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2012, 4, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fixsen, D.L.; Blase, K.A.; Naoom, S.F.; Wallace, F. Core implementation components. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2009, 19, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotzin, A.; Buth, S.; Sehner, S.; Hiller, P.; Martens, M.-S.; Pawils, S.; Metzner, F.; Read, J.; Härter, M.; Schäfer, I.; et al. “Learning how to ask”: Effectiveness of a training for trauma inquiry and response in substance use disorder healthcare professionals. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2018, 10, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niimura, J.; Nakanishi, M.; Okumura, Y.; Kawano, M.; Nishida, A. Effectiveness of 1-day trauma-informed care training programme on attitudes in psychiatric hospitals: A pre–post study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 980–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossen, E.; Hull, R.V. (Eds.) Supporting and Educating Traumatized Students: A Guide for School-Based Professionals; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss-Dagan, S.; Ben-Porat, A.; Itzhaky, H. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious post-traumatic growth among social workers who have worked with abused children. J. Soc. Work 2022, 22, 170–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figley, C.R. (Ed.) Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized; Routledge: London, UK, 1995; Available online: https://www.emdr.org.il/wp-ntent/uploads/2021/08/Figley1995CompassionFatiguebook.pdfco (accessed on 5 March 2023).

- Melinte, B.M.; Turliuc, M.N.; Măirean, C. Secondary traumatic stress and vicarious posttraumatic growth in healthcare professionals: A meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2023, 30, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Jones, J.L.; Macmaster, S.A. Correlates of secondary traumatic stress in child protective services workers. J. Evid. Based Soc. Work 2007, 4, 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson-Gardell, D.; Harris, D. Childhood abuse history, secondary traumatic stress, and child welfare workers. Child Welf. 2003, 82, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.T.; Otis, M.D. Intrapsychic correlates of professional quality of life: Mindfulness, empathy, and emotional separation. J. Soc. Soc. Work Res. 2010, 1, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bride, B.E.; Robinson, M.M.; Yegidis, B.; Figley, C.R. Development and validation of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 2004, 14, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadors, P.; Lamson, A. Compassion fatigue and secondary traumatization: Provider self-care on intensive care units for children. J. Pediatr. Health Care 2008, 22, 24–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dombo, E.A.; Blome, W.W. Vicarious trauma in child welfare workers: A study of organizational responses. J. Public Child Welf. 2016, 10, 505–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.D.; Sprang, G. Compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout in a national sample of trauma treatment therapists. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodeke-Gregson, E.A.; Holttum, S.; Billings, J. Compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress in UK therapists who work with adult trauma clients. Eur. J. Psychotraumatology 2013, 4, 21869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, P. Teaching professionals about trauma-informed practice for children and their families: A toolkit for practitioners. Int. J. Child Maltreatment Res. Policy Pract. 2022, 5, 311–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeCandia, C.; Guarino, K. Trauma-informed care: An ecological response. J. Child Youth Care Work 2015, 25, 7–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julien-Chinn, F.J.; Lietz, C.A. Building learning cultures in the child welfare workforce. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2019, 99, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fansher, A.K.; Zedaker, S.B.; Brady, P.Q. Burnout among forensic interviewers, how they cope, and what agencies can do to help. Child Maltreatment 2020, 25, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, K.P.; Carlson, M.W.; Hatton-Bowers, H.; Fessinger, M.B.; Cole-Mossman, J.; Bahm, J.; Gilkerson, L. Evaluating the facilitating attuned interactions (FAN) approach: Vicarious trauma, professional burnout, and reflective practice. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 112, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; W. H. Freeman: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Benight, C.C.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of posttraumatic recovery: The role of perceived self-efficacy. Behav. Res. Ther. 2004, 42, 1129–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshi, T.; Abu-kaf, S. Burnout and depressive symptoms among social workers: The contribution of conflict management and social support resources. Soc. Welf. 2021, 43, 419–514. [Google Scholar]

- Bonach, K.; Heckert, A. Predictors of secondary traumatic stress among children’s advocacy center forensic interviewers. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2012, 21, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieslak, R.; Shoji, K.; Douglas, A.; Melville, E.; Luszczynska, A.; Benight, C.C. A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 2014, 11, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning-Jones, S.; de Terte, I.; Stephens, C. Secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, and coping among health professionals; A comparison study. N. Z. J. Psychol. (Online) 2016, 45, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach (Methodology in the Social Sciences), 2nd ed.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, F. Partial, conditional, and moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Commun. Monogr. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C.R. Compassion fatigue: Toward a new understanding of the costs of caring. In Secondary Traumatic Stress: Self-Care Issues for Clinicians, Researchers Educators, 2nd ed.; Stamm, B.H., Ed.; Sidran Press: Derwood, MD, USA, 1999; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- David, P.; Schiff, M. Self-efficacy as a mediator in bottom-up dissemination of a research-supported intervention for young, traumatized children and their families. J. Evid. Inf. Soc. Work 2017, 14, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voss Horrell, S.C.; Holohan, D.R.; Didion, L.M.; Vance, G.T. Treating traumatized OEF/OIF veterans: How does trauma treatment affect the clinician? Prof. Psychol. Res. Pract. 2011, 42, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruv Institute. 2019. Available online: https://haruv.org.il/en/ (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Kalaitzaki, A.; Tamiolaki, A.; Tsouvelas, G. From secondary traumatic stress to vicarious posttraumatic growth amid COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: The role of health care workers’ coping strategies. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2022, 14, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Descriptive Statistics | Pearson Correlation Coefficients | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Questionnaire Scales and Sub-Scales | M | SD | Range | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| ARTIC (1) | 5.63 | 0.54 | 4.04–6.76 | −0.23 *** | −0.16 ** | −0.27 *** | −0.21 ** | 0.40 *** |

| STS—Total (2) | 2.18 | 0.72 | 1.06–4.94 | 0.91 *** | 0.94 *** | 0.93 *** | −0.40 *** | |

| Intrusion (3) | 2.38 | 0.79 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.76 *** | 0.80 *** | −0.25 * | ||

| Avoidance (4) | 2.07 | 0.79 | 1.00–5.00 | 0.82 *** | −0.45 *** | |||

| Arousal (5) | 2.12 | 0.74 | 1.00–4.80 | −0.38 *** | ||||

| STSE (6) | 5.67 | 0.75 | 2.14–7.00 | 1 | ||||

| Steps | Explanatory Variables | B | SE.B | β | R2 | ∆R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique contribution of the ARTIC to STS | ||||||

| 1 | Therapists’ age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.30 ** | 0.089 ** | 0.089 ** |

| Therapists’ age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.29 ** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.90 | 0.34 | −0.25 ** | 0.150 *** | 0.061 ** | |

| Therapists’ age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.53 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.86 | 0.33 | −0.24 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.32 * | 0.195 *** | 0.045 * | |

| Therapists’ age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.54 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.83 | 0.33 | −0.23 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.29 * | |||

| Education | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.19 * | 0.229 *** | 0.034 * | |

| 2 | Therapists’ age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.50 *** | ||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | 0.70 | 0.33 | 0.19 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.24 | |||

| Education | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.21 * | |||

| ARTIC | −0.27 | 0.12 | −0.20 * | 0.268 *** | 0.039 * | |

| Unique contribution of the ARTIC to STSE | ||||||

| 1 | Underwent TIC training 1 | 1.29 | 0.36 | 0.34 *** | 0.115 *** | 0.115 *** |

| Underwent TIC training 1 | 1.28 | 0.36 | 0.34 *** | |||

| Therapy setting 2 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.20 * | 0.154 *** | 0.039 * | |

| 2 | Underwent TIC training 1 | 1.06 | 0.34 | 0.28 ** | ||

| Therapy setting 2 | 0.27 | 0.13 | 0.18 * | |||

| ARTIC | 0.46 | 0.12 | 0.33 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.108 *** | |

| Steps | Explanatory Variables | B | SE.B | β | R2 | ∆R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unique contribution of the STSE to STS | ||||||

| 1 | Therapists’ age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.30 ** | 0.089 ** | 0.089 ** |

| Therapists’ age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.29 ** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.90 | 0.34 | −0.25 ** | 0.150 *** | 0.061 ** | |

| Therapists’ age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.53 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.86 | 0.33 | −0.24 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.32 * | 0.195 *** | 0.045 * | |

| Therapists’ age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.54 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.83 | 0.33 | −0.23 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.29 * | |||

| Education | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.19 * | 0.229 *** | 0.034 * | |

| 2 | Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.46 *** | ||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | 0.39 | 0.32 | 0.11 | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.23 | |||

| Education | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.23 ** | |||

| STSE | −0.34 | 0.09 | −0.36 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.110 *** | |

| Unique contribution of the ARTIC and STSE to STS | ||||||

| 1 | Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.30 ** | 0.089 ** | 0.089 ** |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.29 ** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.90 | 0.34 | −0.25 ** | 0.150 *** | 0.061 ** | |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.53 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.86 | 0.33 | −0.24 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.32 * | 0.195 *** | 0.045 * | |

| Age | −0.04 | 0.01 | −0.54 *** | |||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.83 | 0.33 | −0.23 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.29 * | |||

| Education | 0.35 | 0.17 | 0.19 * | 0.229 *** | 0.034 * | |

| 2 | Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.50 *** | ||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.70 | 0.32 | −0.19 * | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.24 * | |||

| Education | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.21 * | |||

| ARTIC | −0.27 | 0.12 | −0.20 * | 0.268 *** | 0.039 * | |

| 3 | Age | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.45 *** | ||

| Underwent TIC training 1 | −0.37 | 0.32 | −0.10 | |||

| Years of seniority as a therapist | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.22 * | |||

| Education | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.24 ** | |||

| ARTIC | −0.13 | 0.12 | −0.10 | |||

| STSE | −31 | 0.09 | −0.32 *** | 0.346 *** | 0.079 *** | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller Itay, M.R.; Turliuc, M.N. Who Will Save the Savior? The Relationship between Therapists’ Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Stress Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13121012

Miller Itay MR, Turliuc MN. Who Will Save the Savior? The Relationship between Therapists’ Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Stress Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(12):1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13121012

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller Itay, Miriam Rivka, and Maria Nicoleta Turliuc. 2023. "Who Will Save the Savior? The Relationship between Therapists’ Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Stress Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 12: 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13121012

APA StyleMiller Itay, M. R., & Turliuc, M. N. (2023). Who Will Save the Savior? The Relationship between Therapists’ Secondary Traumatic Stress, Secondary Stress Self-Efficacy, and Attitudes toward Trauma-Informed Care. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), 1012. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13121012