Chinese Private Preschool Teachers’ Teaching Readiness and Teacher–Child Relationships: The Chain Mediation Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Teaching Readiness (TR) and the Teacher–Child Relationship (TCR)

1.2. Motivation to Teach (MT) as a Mediator

1.3. Self-Efficacy (SE) as a Mediator

1.4. The Chain Mediation Effect of MT and SE

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Teacher–Child Relationship

2.2.2. Teachers’ Teaching Readiness

2.2.3. Teachers’ Motivation to Teach

2.2.4. The Self-Efficacy of Preschool Teachers

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Common Method Bias

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

3.3. Test of the Mediating Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy

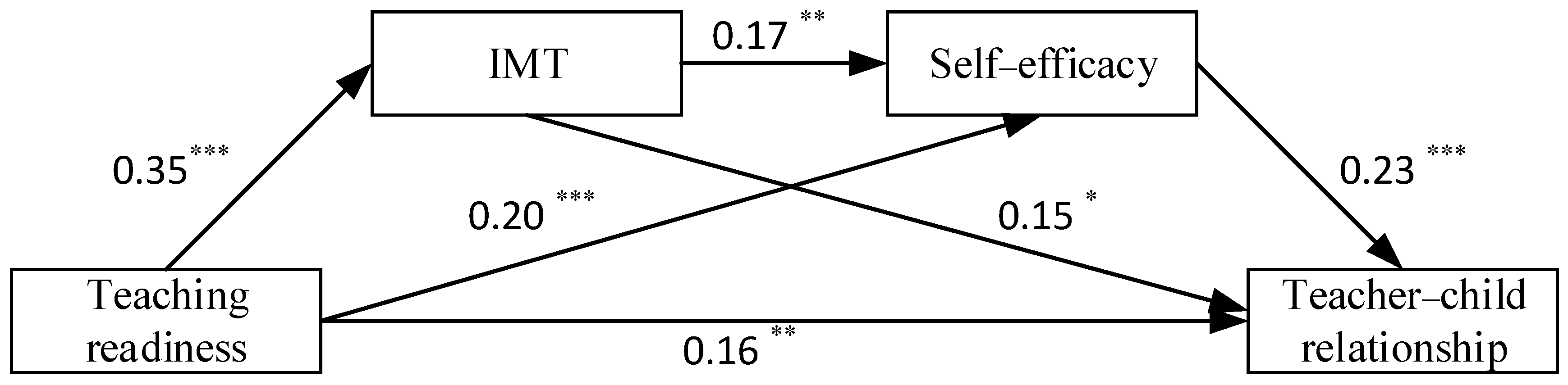

3.3.1. Roles of Teachers’ Internal Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy

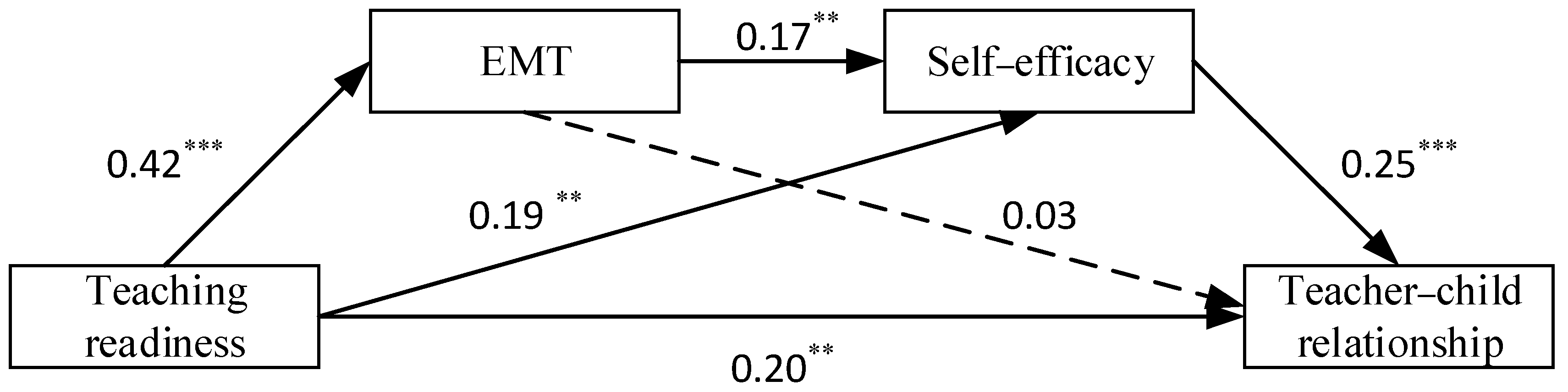

3.3.2. Roles of Teachers’ External Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy

4. Discussion

4.1. The Relationship between TR and Teacher–Child Relationships

4.2. Mediating Role of Teachers’ Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy

4.3. The Chain Mediating Effect of Teachers’ MT and SE

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McNally, S.; Slutsky, R. Teacher–Child Relationships Make All the Difference: Constructing Quality Interactions in Early Childhood Settings. Early Child Dev. Care. 2018, 188, 508–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Association for the Education of Young Children. All Criteria document. Available online: http://www.naeyc.org/files/academy/file/AllCriteriaDocument.pdf (accessed on 16 July 2023).

- Howes, C.; Hamilton, C.E. The changing experience of child care: Changes in teachers and in teacher-child relationships and children’s social competence with peers. Early Child. Res. Q. 1993, 8, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, T.M.; Duncan, R.; Purpura, D.J.; Schmitt, S.A. The relations between teacher-child relationships in preschool and children’s outcomes in kindergarten. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2023, 86, 101534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Fan, X.; Wu, Z.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Yang, N.; Zhang, J. Teacher-child interactions and children’s cognitive and social skills in Chinese preschool classrooms. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 79, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, C.L.; Brown, J.L.; Downer, J.T. Teacher–child relationships, classroom climate, and children’s social-emotional and academic development. J. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 110, 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J. Exploring the impact of teacher emotions on their approaches to teaching: A structural equation modelling approach. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2019, 89, 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K.E. “You choose to care”: Teachers, emotions and professional identity. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2008, 24, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudasill, K.M.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E. Teacher–child relationship quality: The roles of child temperament and teacher–child interactions. Early Child. Res. Q. 2009, 24, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, B.A.; O’Connor, E.E.; Supplee, L.; Shaw, D.S. Behavior problems in elementary school among low-income boys: The role of teacher–child relationships. J. Educ. Res. 2017, 110, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myers, S.S.; Pianta, R.C. Developmental Commentary: Individual and Contextual Influences on Student–Teacher Relationships and Children’s Early Problem Behaviors. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2008, 37, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Pan, B.; Yu, Z.; Song, Z. The relationship between preschool teacher trait mindfulness and teacher-child relationship quality: The chain mediating role of emotional intelligence and empathy. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 17, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moritz Rudasill, K.; Rimm-Kaufman, S.E.; Justice, L.M.; Pence, K. Temperament and Language Skills as Predictors of Teacher-Child Relationship Quality in Preschool. Early Educ. Dev. 2006, 17, 271–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Housego, B.E.J. Student Teachers’ Feelings of Preparedness to Teach. Can. J. Educ. 1990, 15, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwatu, K.O. Preservice teachers’ sense of preparedness and self-efficacy to teach in America’s urban and suburban schools: Does context matter? Teach. Teach. Educ. 2011, 27, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallo, R.; Little, E. Classroom behaviour problems: The relationship between preparedness, classroom experiences, and self-efficacy in graduate and student teachers. Aust. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 2003, 3, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Buyse, E.; Verschueren, K.; Doumen, S. Preschoolers’ Attachment to Mother and Risk for Adjustment Problems in Kindergarten: Can Teachers Make a Difference?: Mother-Child Attachment and Adjustment. Soc. Dev. 2011, 20, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Dobbs-Oates, J. Teacher-Child Relationships: Contribution of Teacher and Child Characteristics. J. Res. Child. Educ. 2016, 30, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degotardi, S. High-quality interactions with infants: Relationships with early-childhood practitioners’ interpretations and qualification levels in play and routine contexts. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2010, 18, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlee, J.; Berthelsen, D.; Irving, K.; Boulton-Lewis, G.; McCrindle, A. Caregivers’ Beliefs about Practice in Infant Child Care Programmes. Int. J. Early Years Educ. 2000, 8, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dörnyei, Z.; Ushioda, E. Teaching and Researching Motivation, 2nd ed.; Longman: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M.; Burden, R.L. Psychology for Language Teachers: A Social Constructivist Approach; Cambrige Univesity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Yin, H. Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Educ. 2016, 3, 1217819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesje, K.; Brandmo, C.; Berger, J.-L. Motivation to Become a Teacher: A Norwegian Validation of the Factors Influencing Teaching Choice Scale. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2018, 62, 813–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. An introduction to teaching motivations in different countries: Comparisons using the FIT-Choice scale. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 40, 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kılınç, A.; Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Factors Influencing Teaching Choice in Turkey. Asia-Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 40, 199–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghtesadi Roudi, A. Why to become a teacher in Iran: A FIT-choice study. Teach. Educ. 2022, 33, 434–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Motivational Factors Influencing Teaching as a Career Choice: Development and Validation of the FIT-Choice Scale. J. Exp. Educ. 2007, 75, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blömeke, S.; Houang, R.T.; Hsieh, F.-J.; Wang, T.-Y. Effects of Job Motives, Teacher Knowledge, and School Context on Beginning Teachers’ Commitment to Stay in the Profession. In International Handbook of Teacher Quality and Policy; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collie, R.J.; Martin, A.J. Adaptive and maladaptive work-related motivation among teachers: A person-centered examination and links with well-being. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 64, 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karabenick, S.; Urdan, T. (Eds.) Applications and Contexts of Motivation and Achievement, 1st ed.; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, H.; Yao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, X. The influence of teachers’ intrinsic motivation on students’ intrinsic motivation: The mediating role of teachers’ motivating style and teacher-student relationships. Psychol. Sch. 2023; advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond-West, T.; Rangel, V.S. Teacher Preparation and Novice Teacher Self-Efficacy in Literacy Instruction. Educ. Urban Soc. 2020, 52, 534–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. The differential antecedents of self-efficacy beliefs of novice and experienced teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2007, 23, 944–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C.J.; Bruder, M.B. Preservice Professional Preparation and Teachers’ Self-Efficacy Appraisals of Natural Environment and Inclusion Practices. Teach. Educ. Spec. Educ. J. Teach. Educ. Div. Counc. Except. Child. 2014, 37, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, L.; Parsad, B.; Carey, N.; Bartfai, N.; Farris, E.; Smerdon, B. Teacher Quality: A Report on the Preparation and Qualifications of Public School Teachers (NCES 1999-080); National Center for Education Statistics, US Department of Education: Washington, DC, USA, 1999.

- Hajovsky, D.B.; Chesnut, S.R.; Jensen, K.M. The role of teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs in the development of teacher-student relationships. J. Sch. Psychol. 2020, 82, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, J.J.; Davis, H.A.; Hoy, A.W. The effects of teachers’ efficacy beliefs on students’ perceptions of teacher relationship quality. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2017, 53, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyano, N.; Perez-Yus, M.C.; Herrera-Mercadal, P.; Navarro-Gil, M.; Valle, S.; Montero-Marin, J. Burned or engaged teachers? The role of mindfulness, self-efficacy, teacher and students’ relationships, and the mediating role of intrapersonal and interpersonal mindfulness. Curr. Psychol. 2023, 42, 11719–11732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W. Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2001, 17, 783–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilim, I. Pre-service Elementary Teachers’ Motivations to Become a Teacher and its Relationship with Teaching Self-efficacy. Procedia–Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 152, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A.G.; Auerswald, S.; Seinsche, A.; Saul, I.; Klocke, H. German student teachers’ decision process of becoming a teacher: The relationship among career exploration and decision-making self-efficacy, teacher motivation and early field experience. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2021, 105, 103350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainley, J.; Carstens, R. Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 Conceptual Framework; OECD Education Working Papers, No. 187; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen-Moran, M.; Hoy, A.W.; Hoy, W.K. Teacher Efficacy: Its Meaning and Measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 1998, 68, 202–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamre, B.K.; Pianta, R.C.; Burchinal, M.; Field, S.; LoCasale-Crouch, J.; Downer, J.T.; Howes, C.; LaParo, K.; Scott-Little, C. A Course on Effective Teacher-Child Interactions: Effects on Teacher Beliefs, Knowledge, and Observed Practice. Am. Educ. Res. J. 2012, 49, 88–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.Y.; Fan, X.; Yang, Y.; Neitzel, J. Chinese preschool teachers’ knowledge and practice of teacher-child interactions: The mediating role of teachers’ beliefs about children. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2017, 63, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, A.C.; King, M.A. Creating a Climate of Self-Awareness in Early Childhood Teacher Preparation Programs. Early Child. Educ. J. 2006, 33, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, K.L.; McWilliam, R.A.; Louise Hemmeter, M.; Ault, M.J.; Schuster, J.W. Predictors of developmentally appropriate classroom practices in kindergarten through third grade. Early Child. Res. Q. 2001, 16, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, S. Quality Evaluation and Quality Enhancement in Preschool: A Model of Competence Development. Early Child Dev. Care 2001, 166, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sang, G.; He, W. Motivation to teach and preparedness for teaching among preservice teachers in China: The effect of conscientiousness and constructivist teaching beliefs. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1116321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Teachers’ motivation for entering the teaching profession and their job satisfaction: A cross-cultural comparison of China and other countries. Learn. Environ. Res. 2014, 17, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarides, R.; Watt, H.M.G.; Richardson, P.W. Does school context moderate longitudinal relations between teacher-reported self-efficacy and value for student engagement and teacher-student relationships from early until midcareer? Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2023, 72, 102136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2020, 61, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, J.; Qin, X.-x. Investigating the Influence of Primary and Secondary Teachers’ Motivation for Teaching on Job Burnout: Testing the Mediating Role of Social-Emotional Competence. Teach. Educ. Res. 2023, 35, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupnisky, R.H.; BrckaLorenz, A.; Yuhas, B.; Guay, F. Faculty members’ motivation for teaching and best practices: Testing a model based on self-determination theory across institution types. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2018, 53, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. The Impact of Teaching Readiness on Teachers’ Professional Development Needs: Self-efficacy and Job Satisfaction as Mediator. Sci. Explor. Educ. 2023, 41, 6–14. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H.; Tam, W.W.Y.; Lau, E. Examining the relationships between teachers’ affective states, self-efficacy, and teacher-child relationships in kindergartens: An integration of social cognitive theory and positive psychology. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2022, 74, 101188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raudenbush, S.W.; Bryk, A.S. Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teaching readiness | 1.00 | ||||

| 2. External motivation to teach | 0.417 ** | 1.00 | |||

| 3. Internal motivation to teach | 0.346 ** | 0.635 ** | 1.00 | ||

| 4. Teacher–child relationship | 0.271 ** | 0.168 ** | 0.257 ** | 1.00 | |

| 5. Self-efficacy | 0.262 ** | 0.247 ** | 0.244 ** | 0.305 ** | 1.00 |

| M | 3.13 | 3.60 | 3.80 | 3.59 | 3.99 |

| SD | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.38 | 0.56 | 0.63 |

| Regression Equation | Overall Fitting Index | Significance of Regression Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome Variables | Predictive Variables | R | R2 | F | β | t |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| IMT | TR | 0.35 | 0.12 | 39.07 *** | 0.35 | 6.25 *** |

| SE | TR | 0.31 | 0.10 | 15.03 *** | 0.20 | 3.36 *** |

| IMT | 0.17 | 2.91 ** | ||||

| TCR | TR | 0.39 | 0.15 | 16.85 *** | 0.16 | 2.72 ** |

| IMT | 0.15 | 2.47 * | ||||

| SE | 0.23 | 3.96 *** | ||||

| Model 2 | ||||||

| EMT | TR | 0.42 | 0.17 | 60.33 *** | 0.42 | 7.77 *** |

| SE | TR | 0.30 | 0.09 | 14.38 *** | 0.19 | 3.10 ** |

| EMT | 0.17 | 2.70 ** | ||||

| TCR | TR | 0.37 | 0.13 | 14.56 *** | 0.20 | 3.17 ** |

| EMT | 0.03 | 0.42 | ||||

| SE | 0.25 | 4.28 *** | ||||

| Pathway | Estimate | Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||

| Model 1 | ||||

| TR—IMT—TCR | 0.051 | 18.82% | 0.014 | 0.090 |

| TR—IMT—SE—TCR | 0.013 | 4.80% | 0.004 | 0.028 |

| TR—SE—TCR | 0.046 | 16.97% | 0.013 | 0.088 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.110 | 40.59% | 0.058 | 0.172 |

| Direct effect | 0.161 | 59.41% | 0.045 | 0.278 |

| Total effect | 0.271 | 100.00% | 0.159 | 0.383 |

| Model 2 | ||||

| TR—EMT—TCR | 0.011 | 4.06% | −0.041 | 0.058 |

| TR—EMT—SE—TCR | 0.017 | 6.274% | 0.006 | 0.034 |

| TR—SE—TCR | 0.047 | 17.34% | 0.013 | 0.094 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.075 | 27.68% | 0.013 | 0.144 |

| Direct effect | 0.196 | 72.32% | 0.074 | 0.317 |

| Total effect | 0.271 | 100.00% | 0.159 | 0.383 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, H.; Chen, W.; He, H.; Luo, W. Chinese Private Preschool Teachers’ Teaching Readiness and Teacher–Child Relationships: The Chain Mediation Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110900

Li H, Chen W, He H, Luo W. Chinese Private Preschool Teachers’ Teaching Readiness and Teacher–Child Relationships: The Chain Mediation Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 13(11):900. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110900

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Hui, Wei Chen, Huihua He, and Wenwei Luo. 2023. "Chinese Private Preschool Teachers’ Teaching Readiness and Teacher–Child Relationships: The Chain Mediation Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy" Behavioral Sciences 13, no. 11: 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110900

APA StyleLi, H., Chen, W., He, H., & Luo, W. (2023). Chinese Private Preschool Teachers’ Teaching Readiness and Teacher–Child Relationships: The Chain Mediation Effects of Motivation to Teach and Self-Efficacy. Behavioral Sciences, 13(11), 900. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13110900