Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Identification of the Research Question

2.3. Identification of Studies

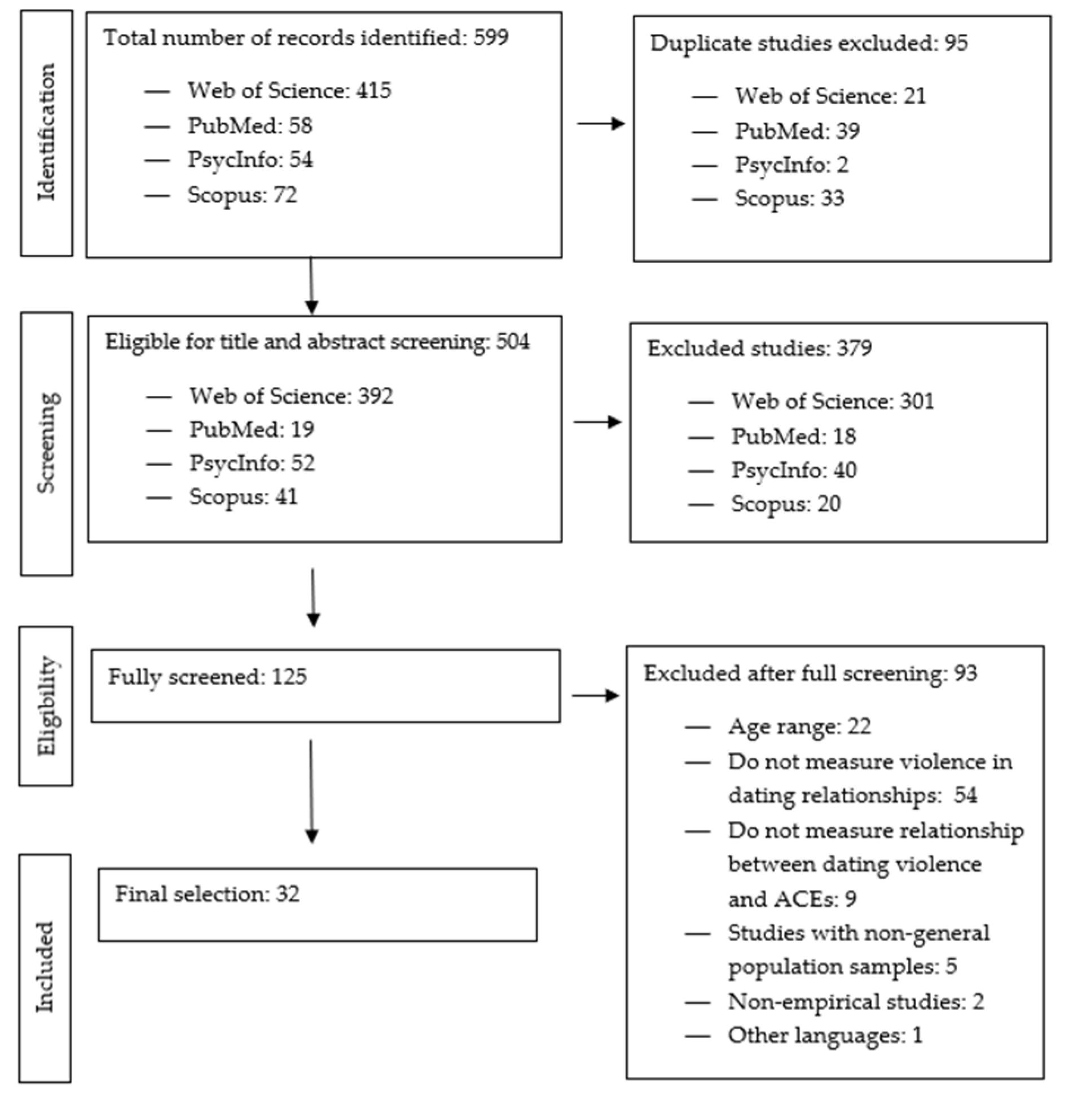

2.4. Study Selection

2.5. Charting and Data Analysis

2.6. Study Rigour

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Methodological Differences

3.3. Study Rigour Scores

3.4. Primary Analyses

3.4.1. Findings on Global Dating Violence and ACEs

3.4.2. Physical Dating Violence and ACEs

Childhood Physical Abuse

Childhood Psychological/Emotional Abuse

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Witnessing Interparental Violence

Parental Neglect

Other Adverse Childhood Experiences

3.4.3. Emotional and Psychological Dating Violence and ACEs

Childhood Physical Abuse

Childhood Psychological/Emotional Abuse

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Witnessing Interparental Violence

Parental Neglect

Other Adverse Childhood Experiences

3.4.4. Sexual Dating Violence and ACEs

Childhood Physical Abuse

Childhood Psychological/Emotional Abuse

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Witnessing Interparental Violence

Neglect

Other Adverse Childhood Experiences

3.4.5. Cyber Dating Abuse and ACEs

Childhood Physical Abuse

Childhood Psychological/Emotional Abuse

Childhood Sexual Abuse

Witnessing Interparental Violence

Parental Neglect

Other Adverse Childhood Experiences

Combined Forms of Dating Violence and ACEs

Other Forms of Dating Violence and ACEs

Sex Differences in the Relationship between Dating Violence and ACEs

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Participants | Aim of the Study | Study Design | Types of Dating Violence Analysed | Roles in Dating Violence Examined | Instrument Use to Measure Dating Violence | Aces Analysed | Instrument Use to Measure Aces | Statistical Analyses included to Test the Association between Aces and Dating Violence | Key Findings about the Relationship between Aces and Dating Violence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | N = 99 men Age range is not specified Mean age reported = 20 years old | Examine the association between witnessing interparental violence as a child, being a victim of parental physical violence, and perpetrating violence in dating relationship. | Cross-sectional | Physical and Sexual violence | Perpetration | The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus & Gelles, 1986). The Sexual Experiences Survey, male version (SES, Koss & Oros, 1982) | Witnessing interparental violence Parental physical violence. | The Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus & Gelles, 1986) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Witnessing interparental violence was related to perpetration of physical dating violence but not sexual violence. Experiencing child abuse by a parental figure was not significantly related to the perpetration of dating violence forms examined |

| [51] | N = 1569 women Age = 18–19 years old | Assess the extent to which experiences of childhood victimisation predicts physical dating victimisation in high school and in college. | Longitudinal | Physical and Sexual violence | Victimization | A modified version of the violence subscale of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS, Straus, 1979) | Sexual and physical abuse Witnessing interparental violence | Several measures | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Women physically or sexually victimised or covictimised across the 4 years of college were those with a history of both childhood victimisation (any type) and physical victimisation in adolescence. However, young women who were abused in childhood but not in adolescence were not at greater risk for physical victimization. |

| [52] | N = 325 men Age = 18–19 years old | Examine the relationship between childhood sexual assault and subsequent perpetration of dating violence in adulthood | Longitudinal | Sexual violence | Perpetration | Sexual Experiences Survey (SES, Koss & Oros, 1982). The Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS, Straus, 1979) | Sexual abuse | Child Sexual Victimization Questionnaire (CSVQ, Finkelhor, 1979) Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS, Straus, 1979) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Retrospective analyses showed a relationship between childhood sexual victimisation and perpetration of sexual aggression in adulthood at baseline. Prospective analyses showed that childhood sexual victimisation was not predictive of perpetration during the follow-up period |

| [53] | N = 100 men and 100 women Age = 18–24 years old | Empirically evaluate the Riggs and O’Leary (1989) model of dating violence | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Perpetration | The Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1979) | Parent–child violence Witnessing interparental violence | The Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS; Straus, 1979) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Women with violent fathers were three time more likely to perpetrate dating violence. The same relationships were not found among male participants. |

| [54] | N = 374 women Age range is not reported Mean age reported = 18.54 (SD = 0.87) | Explore women’s perpetration of dating aggression within the context of childhood and adolescent victimisation experiences | Longitudinal | Verbal and physical violence | Perpetration | The Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS, Straus, 1979) | Childhood sexual, physical and verbal abuse. | Child Sexual Victimization Questionnaire (CSVQ, Finkelhor, 1979; Risin & Koss, 1987). The Conflict Tactic Scales (CTS, Straus, 1979) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Retrospective analyses showed that 1) paternal physical abuse predicted women’s reports of verbal perpetration.2) Childhood sexual abuse predicted women’s reports of physical perpetration. Prospective analyses showed that childhood abuse variables were not predictive of women’s engagement in physical or verbal perpetration over the follow-up period. |

| [39] | N = 327 Women Age = 18–40 years old | Examine whether fearful dating experiences may help explain the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and dating violence | Cross-sectional | Sexual, emotional and physical violence | Victimization | The Conflict Tactics Scale (MCTS, Straus, 1979) | Childhood sexual abuse | Sexual Experiences Survey (SES, Koss & Oros, 1982) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: fearful dating experiences as mediator of the relationship between Childhood Sexual Abuse and dating victimisation. | Women who reported experiences of childhood sexual abuse were more likely to report dating violence victimisation. The relationship was reduced after controlling for fear in dating relationships. |

| [55] | N = 703 men and women Age = 18–30 years old. | Examine whether witnessing interparental violence, childhood physical and emotional abuse were related to reports of physical aggression perpetration and victimisation in dating relationships | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al. 1996) | Witnessing interparental violence Childhood physical and emotional abuse | The Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS2-CA; Straus, 2000) Exposure to Abusive and Supportive Environments Parenting Inventory (EASE-PI, Nicholas & Bieber 1997) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Moderation analyses conducted: Gender was tested as moderator. | Witnessing interparental violence and experiencing childhood abuse was associated with reports of dating violence perpetration and victimisation. Associations differed according to parent and child gender. |

| [56] | N = 1.399 US women and men N = 1.588 SK women and men. Age range is not specified | Examine associations between childhood maltreatment and dating violence among U.S. and South Korean college students | Cross-sectional | Psychological and physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Childhood physical abuse Witnessing interparental violence | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Childhood physical abuse was positively related with psychological dating victimisation and perpetration in both samples. Witnessing interparental violence was not consistently related with involvement in dating violence. |

| [57] | N = 5130 women and men Age range = 21–56 years | Examine the associations of co-occurring childhood adversities with physical violence in dating relationships | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) | 12 childhood adversities: Parental death, parental divorce, other long-term parental separation, parental mental illness, parental substance use disorder, parental criminality, interparental violence, serious illness in childhood, physical and sexual abuse, neglect, family economic adversity | Multiple measures | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Cumulative ACES association with dating violence tested | 10 of the 12 childhood adversities examined were significantly associated with physical dating perpetration and victimisation. Sexual abuse, interparental violence and parent mental illness were the childhood adversities associate in a highest proportion with physical dating violence |

| [58] | N = 900 women and men Age = 18–26 years old. | Examine the effects of poor parenting and child abuse on dating violence perpetration and victimisation | Longitudinal | Emotional, physical, and sexual violence | Victimisation and perpetration | Ad hoc questionnaire | Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, neglect and lack of parental warmth | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) was used to measure childhood abuse. Ad hoc questionnaire was used to measure lack of parental warmth. | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Substance use and delinquency were tested as mediators | Neglect and low parental warmth were directly associated with dating violence perpetration. Physical abuse and low parental warmth were directly associated with dating violence victimisation Delinquency increased the relationship between physical abuse, lack of parental warmth and dating violence victimisation and perpetration |

| [59] | N = 570 women and men Age = 18–28 years old | Examine men and women perpetration of dating violence and its relationship with child maltreatment | Cross-sectional | Physical, sexual, and psychological violence | Perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS–2; Straus et al., 1996) | Physical, psychological, and sexual abuse, and neglect | The Comprehensive Childhood Maltreatment Scale (CCMS; Higgins & McCabe, 2001). | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Childhood experiences of maternal neglect were positively related to men’s physical perpetration. Childhood sexual abuse predicted women’s sexual perpetration and men’s psychological perpetration |

| [60] | N = 1399 women and men Age range is not specified. Mean age reported = 19.92 (SD = 1.12) | Examine whether child physical abuse is a causal factor in adult dating violence victimisation and perpetration | Quasi-experimental | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS–2; Straus et al., 1996) | Physical abuse Witnessing interparental violence | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS–2; Straus et al., 1996) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Propensity score matching approach with 29 covariates as potential confounders including: Witnessing interparental violence, maternal and paternal support, religiosity, substance use, self-control, risky sexual behaviour, and several demographic variables. | Child physical abuse is associated with adult dating violence, However, there is a spurious relationship. The relationship likely exits in tandem with other problems within the family such as witnessing interparental violence. |

| [61] | N = 484 women and men Age range is not specified. Mean age reported = 20.81 (SD = 1.81) | Explain how sibling violence perpetrations and attachment styles mediate the relationship between child maltreatment and dating violence perpetration | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS–2; Straus et al., 1996) | Physical abuse | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS–2; Straus et al., 1996) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Attachment style and sibling violence perpetration were tested as mediators. | Men: Parent-to-child victimisation was directly associated with dating violence perpetration. The hypothesized mediational model was not supported. Women: Parent-to-child victimisation was directly associated with dating violence perpetration. Sibling violence perpetration and attachment styles also served a mediating role between child abuse and dating violence. |

| [62] | N = 4162 women and men Age range is not specified. Mean age reported = 22 years old. | Examine the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and adult dating violence perpetration and victimisation | Quasi-experimental | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) | Sexual abuse | The Personal and Relationships Profile (PRP, Straus, Mouradian, & DeVoe, 1999) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Propensity score matching approach with 18 covariates as potential confounders including: Child physical abuse, Witnessing interparental violence, substance use, self-control, criminal history, and several demographic variables. | Experiencing child sexual abuse influences adult dating violence victimisation and perpetration. This relationship remained significant after the potential confounders were included in the analysis. |

| [63] | N = 3322 women and men Age = 19–22 years old. | Examine whether distinct types of childhood maltreatment differentially are associate with dating violence victimisation controlling for individual and family confounders | Longitudinal | Emotional and physical violence, harassment and severe combined abuse | Victimisation | The Revised Composite Abuse Scale (CAS, Hegarty et al. 2005) | Physical and emotional abuse Physical and emotional neglect | Cases of child maltreatment were identified through state-wide child protection records. | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Relationships measured adjusting for 11 confounders including social deprivation, aggressive behavior, maternal stress, maternal negative life events, family violence | Participants who experienced any form of child maltreatment were more likely to report emotional and/or physical victimisation in dating relationships. |

| [64] | N = 293 women Age range is not reported Mean age reported = 22.8 (SD = 6.9) | Examine the relationship between child abuse and intimate pattern violence victimisation | Cross-sectional | Psychological and physical violence, injury, sex pursuant to insisting, threats, and force | Victimisation | The Revised Conflict Tactic Scale (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) | Neglect, physical and sexual abuse | The Personal and Relationships Profile (PRP; Straus et al., 1999) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Women characterized by a high intimate partner violence victimisation profile were the most likely to have experienced neglect, physical and sexual abuse in childhood |

| [65] | N = 1482 women and men Age range and mean age not reported | To examine the role of child abuse, self-control, entitlement, and risky behaviours on dating violence perpetration among college students from one Southeastern and one Midwestern university in the United States | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Physical abuse | The Parent–child Conflict Tactics Scale (PC-CTS; Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Self-control and General Entitlement and risky behaviours (drinking, drug use and sexual risk behaviour) were tested as mediators. | Students who reported perpetrating dating violence were significantly more likely to have experienced more physical abuse Child physical abuse was also linked to dating violence perpetration through the mediation of lower self-control. and its association with risky behaviours. |

| [67] | N = 3344 women and men Age range: 18–25 years old | Examine the shared and sex-specific background-situational correlates of dating violence typologies among college students | Cross-sectional | Physical assault, sexual coercion, and psychological violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Childhood violent socialization, sexual abuse | The Personal and Relationships Profile (PRP; Straus et al., 2010) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Childhood violent socialization and sexual abuse history were not significantly associated with the different dating violence typologies examined among women and men college students. |

| [66] | N = 807 women and men Age range not reported Mean age reported = 20.89 (SD = 3.54) | Examine the association between childhood family violence and involvement in mutual dating violence | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Interparental violence, Punitive discipline | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) The Dimensions of Discipline Inventory-Adult Recall form (DDI; Straus & Fauchier, 2007) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Violence approval, negative relating to others, negative relation to mother and father, and closeness to mother and father were tested as mediators. | Mother’s punitive discipline affected mutual dating violence through the mediation of violence approval and negative relating to others. Mutual interparental violence had a direct effect on mutual dating violence and an indirect effect via violence approval, negative relating to mother, and less closeness to mother |

| [68] | N = 60 women and men Age range = 18–33 years old | Examine the relation between childhood emotional maltreatment and perpetration of psychological violence | Cross-sectional | Psychological violence | Perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus & Douglas, 2004) | Physical, emotional and sexual abuse, physical and emotional neglect | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein & Fink, 1998) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Moderation analyses conducted: Skilful emotion communication was tested as a moderator | Higher levels of childhood emotional maltreatment were associated with higher levels of self-reported dating psychological violence. Higher skilful emotion communication attenuated associations between childhood emotional maltreatment and dating psychological violence, but only for women |

| [69] | N = 3495 women and men Age range = 18–25 years old | Examine the relationships between violent socialization, family social structure, relationship dynamic factors and dating violence among college students. | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996) | Violent socialization: childhood neglect, harsh corporal punishment, and witnessing interparental violence | Ad hoc questionnaire | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Interaction analyses conducted: Combinations of variables measuring violent socialization, family social structure and relationships dynamics were created to explore the underlying relationships of these variables with dating violence. | Childhood neglect and witnessing interparental violence were significantly related to physical dating violence victimisation and perpetration. Interaction effects: Adverse early socialization variables were associated with higher levels of physical dating violence victimisation and perpetration if they also experience psychological violence in their dating relationships |

| [70] | N = 704 women and men Age range and mean age not reported | Examine both risk and protective factors for dating violence perpetration and victimisation. | Cross-sectional | Physical violence | Victimisation and perpetration. | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2, Straus et al., 1996). | Child physical abuse, Witnessing interparental violence, Inconsistent discipline, Maternal and parental relationship quality | Multiple measures | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Childhood physical abuse was positively associated with dating violence perpetration and victimisation. Maternal relationship quality was associated with a lower risk of perpetrating dating violence. |

| [71] | N = 423 men Age range = 18–29 years old | Examine the indirect effect of witnessing interparental violence on cyber partner abuse through attitudes toward violence, controlling effects of childhood maltreatment and face-to-face partner abuse. | Cross-sectional | Cyber abuse: psychological, stalking, and sexual perpetration Face-to-face abuse: sexual, physical, and psychological abuse | Perpetration | Cyber Aggression in Relationships Scale (CARS; Watkins et al., 2018). Conflict Tactics Scale 2 Short Form (CTS2-SF; Straus & Douglas, 2004) | Witnessing interparental violence Emotional, sexual and physical abuse Emotional and physical neglect. | Computer Assisted Maltreatment Inventory (CAMI, DiLillo et al., 2010) The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Attitudes toward violence was tested as a mediator. | Participants reporting witnessing interparental violence in childhood held attitudes justifying intimate partner violence that were associated with perpetrating the three types of cyber abuse examined. |

| [72] | N = 504 women and men Age range = 18–21 years old | Examine overlapping and distinct correlates of psychological and physical dating violence perpetration in emerging adults. | Cross-sectional | Physical and psychological violence | Perpetration | The Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relation-ships Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2001) | Physical and emotional abuse. Witnessing interparental violence | Exposure to Abusive and Support Environments: Parenting Inventory (EASE-PI; Nicholas & Bieber, 1997) Juvenile Victimisation Questionnaire (JVQ; Hamby, Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2004) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Moderation analyses conducted: Insecure/anxious attachment, anger and hostility were tested as moderators. | Physical child abuse and witnessing interparental violence were physical dating violence perpetration. Moderation effects were not found. |

| [73] | N = 395 women and men Age range = 17–23 years old | Examine the relationship between dating violence, childhood trauma, trait anxiety, depression, and anxious attachment | Cross-sectional | Threatening behaviour Relational, physical, sexual and emotional abuse | Victimisation and perpetration | The Conflict in Adolescent Dating Relationships Inventory (CADRI; Wolfe et al., 2001) | Emotional, physical and sexual abuse Emotional and physical neglect | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Dating violence perpetration and victimisation were significantly related to four forms of childhood trauma: physical and emotional abuse, physical and emotional neglect. |

| [40] | N = 423 men Age range = 18–61 years old | Examine the relationships between childhood physical, emotional and sexual abuse, and interpersonal violence between intimate partners | Cross-sectional | Physical, sexual, and psychological violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflicts Tactics Scale (CTS2; Straus et al. 1996) The Sexual Experiences Short Form Perpetration and Victimisation (SES-SFP; SES-SFV; Koss et al., 2006). | Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ; Bernstein et al., 1994) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence | Childhood physical abuse was related with perpetration (psychological, polyperpetration) and victimisation (sexual, psychological, polyvictimisation). Childhood sexual abuse was related with perpetration (physical, sexual, polyperpetration) and victimisation (physical, sexual). Childhood emotional abuse was related with physical and psychological victimisation. |

| [74] | N = 228 women and men Age range = 18–24 years old | Examine adverse childhood experiences in relation to relationship communication quality and intimate partner violence | Cross-sectional | Physical, emotional, sexual, and cyber abuse | Victimisation and perpetration | The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale-Short (Straus & Douglas, 2004). The Abusive Behavior Inventory (ABI, Shepard & Campbell, 1992). Partner Cyber Abuse Questionnaire (Hamby, 2013) | Physical neglect, emotional abuse, and abuse experienced due to dysfunctional households | Adverse childhood experiences Questionnaire (Felitti et al., 1998). | Bivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Dichotomized ACEs scores were created: Low exposure (≤3 ACEs) and high exposure (≥4 ACEs) | Men and women showed moderate associations between the exposure to adverse childhood experiences and victimisation as well as perpetration of physical, emotional, sexual, and cyber abuse. |

| [75] | N = 134 women and men Age range = 18–30 years old | Examine the relationships between adverse childhood experiences, early maladaptive schemas and cyber dating abuse. | Cross-sectional | Various types of cyber dating abuse: aggression, threats, control, privacy intrusion, identity theft, and pressure for sexual behaviours or for sharing sexual images | Victimisation and perpetration | The Digital dating abuse (DDA, Reed et al., 2017) The Cyber Dating Abuse Questionnaire (Borrajo et al., 2015) | Physical, emotional and sexual abuse Physical and emotional neglect Witnessing Interparental Violence | The Childhood Trauma Questionnaire–Short Form (CTQ-SF; Bernstein et al., 2003). Ad hoc items to measure witnessing interparental violence. | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Mediational path analysis: Early maladaptive schemas (emotional deprivation and abandonment) were tested as mediators. | Emotional abuse and physical neglects were related to women’s and men’s perpetration and victimisation through the mediation of the internationalization of the emotional deprivation schema. Witnessing intimate partner violence by the opposite-sex was related to women’s and men’s tendency to control and monitor their partners online. |

| [24] | N = 3279 women and men Age range = 21–22 years old. | Examine risk factors for dating violence occurring up to age 21 in a large UK population-based birth cohort. | Longitudinal | Emotional, physical and sexual violence | Victimisation and perpetration | The IPV measure was based on a previous National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) questionnaire (Barter et al., 2009). | Sexual, physical and emotional abuse. Emotional neglect Substance abuse by parents Parental mental illness or suicide attempt Witnessing interparental violence Parental crime conviction Parental separation Bullying | The Questionnaire from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC, Houtepen et al. 2018) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Cumulative ACES association with dating violence tested | Risk of victimisation increased if the adverse childhood experiences were reported before age 16 for most types, except emotional neglect for either sex, bullying for men, or witnessing violence between parents for women Risk for perpetration also increased for both men and women exposed to adverse childhood experiences before age 16 for most categories |

| [76] | N = 284 women and men Age range not reported. Mean age reported = 20.05 (SD = 2.5) | Examine the relation between adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence in emerging adulthood | Cross-sectional | Physical and psychological violence, injury | Victimisation and perpetration | The Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) | Emotional, physical and sexual abuse Emotional and physical neglect Witnessing interparental violence, Parental mental illness Substance abusing Household member incarceration | The Adverse Childhood Experiences Survey (Felitti et al., 1998) | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Cumulative ACES association with dating violence tested | Witnessing domestic violence was associated with perpetration and victimisation of physical violence and injury. Household member incarceration and physical abuse were associated with physical violence perpetration No cumulative associations were observed. |

| [77] | N = 359 women an men Age range: 18–27 years old. | Explore the relation between family-of-origin violence history and electronic dating violence perpetration. Examine whether perspective taking, and empathy moderated the association between family-of-origin aggression and electronic dating aggression. | Cross-sectional | Cyber dating abuse | Perpetration | The How Friends Treat Each Other Questionnaire (Bennett et al., 2011) | Parent-to child violence, parent-to-parent violence | The Modified Domestic Conflict Inventory (Margolin, John, & Foo, 1998) The Conflict Tactics Scales–Parent/Child (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) | Multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Moderation analysis conducted: Perspective-taking, and empathy were tested as moderators. | Participants who reported greater family-of-origin aggression also reported greater electronic dating violence perpetration. Higher perspective-taking and empathy separately lowered the association between family violence and dating violence perpetration. |

| [78] | N = 1432 women and men Age range and mean age not reported | Examine the role of poor parenting, child abuse, attachment style and risky sexual and drug use behaviours on dating violence perpetration among university students. | Cross-sectional | Physical and psychological violence | Perpetration | The Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (CTS2; Straus et al., 1996) | Child physical abuse. Witnessing parental violence. Maternal relationship quality. | The Conflict Tactics Scales–Parent/Child (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) Ad hoc questionnaires | Bivariate and multivariate analysis between ACEs and dating violence Moderation analysis conducted: Attachment style and risky behaviours were tested as moderators. | Child physical abuse and poorer maternal relationships quality were directly associated with dating violence perpetration. Witnessing parental violence was associated with perpetration on those participants engaged in more sexual risk behaviours. |

References

- Kaura, S.A.; Lohman, B.J. Dating violence victimization, relationship satisfaction, mental health problems, and acceptability of violence: A comparison of men and women. J. Fam. Violence 2007, 22, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birkley, E.L.; Eckhardt, C.L.; Dykstra, R.E. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms, intimate partner violence, and relationship functioning: A meta-analytic review. J. Trauma Stress 2016, 29, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes, M.E.; Simpson, L.; Sullivan, T.P.; Contractor, A.A.; Weiss, N.H. Intimate partner violence and mental health outcomes among Hispanic women in the United States: A scoping review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rey-Anacona, C.A. Prevalencia, Factores de Riesgo y Problemáticas Asociadas con la Violencia en el Noviazgo: Una Revisión de la Literatura. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2008, 26, 227–241. Available online: https://revistas.urosario.edu.co/index.php/apl/article/view/64 (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Víllora, B.; Navarro, R.; Yubero, S. The Role of Social-Interpersonal and Cognitive-Individual Factors in Cyber Dating Victimization and Perpetration: Comparing the Direct, Control, and Combined Forms of Abuse. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 8559–8584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjödin, A.K.; Wallinius, M.; Billstedt, E.; Hofvander, B.; Nilsson, T. Dating violence compared to other types of violence: Similar offenders but different victims. Eur. J. Psychol. Appl. Leg. Context 2017, 9, 83–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stonard, K.E.; Bowen, E.; Lawrence, T.R.; Price, S.A. The relevance of technology to the nature, prevalence and impact of adolescent dating violence and abuse: A research synthesis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 19, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A. Prevalence of violence against dating partners by male and female university students worldwide. Violence Against Women 2004, 10, 790–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preventing Teen Dating Violence. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/features/dating-violence/index.html (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Barter, C.; Stanley, N. Inter-personal violence and abuse in adolescent intimate relationships: Mental health impact and implications for practice. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2016, 28, 485–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.; Thomas, K.A.; Higdon, J. Intimate partner violence, health, sexuality, and academic performance among a national sample of undergraduates. J. Am. Coll. Health 2018, 66, 683–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquette, S.R.; Monteiro, D.L.M. Causes and consequences of adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. J. Inj. Violence Res. 2019, 11, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S.H. The power of family and community factors in predicting dating violence: A meta-analysis. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2018, 40, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass, N.; Fredland, N.; Campbell, J.; Yonas, M.; Sharps, P.; Kub, J. Adolescent dating violence: Prevalence, risk factors, health outcomes, and implications for clinical practice. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. 2003, 32, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froidevaux, N.M.; Metcalf, S.; Pettit, C.; Penner, F.; Sharp, C.; Borelli, J.L. The link between adversity and dating violence among adolescents hospitalized for psychiatric treatment: Parental emotion validation as a candidate protective factor. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP3492–NP3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.J.; Anda, R.F.; Nordenberg, D.; Williamson, D.F.; Spitz, A.M.; Edwards, V.; Marks, J.S. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am. J. Prev. Med. 1998, 14, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anda, R.F.; Butchart, A.; Felitti, V.J.; Brown, D.W. Building a framework for global surveillance of the public health implications of adverse childhood experiences. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2010, 39, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felitti, V.; Anda, R. The relationship of adverse childhood experiences to adult medical disease, psychiatric disorders and sexual behavior: Implications for healthcare. In The Impact of Early Life Trauma on Health and Disease: The Hidden Epidemic; Lanius, R., Vermetten, E., Pain, C., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2010; pp. 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Probst, J.C.; Radcliff, E.; Bennett, K.J.; McKinney, S.H. Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among US children. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 92, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardner, R.; Feely, A.; Layte, R.; Williams, J.; McGavock, J. Adverse childhood experiences are associated with an increased risk of obesity in early adolescence: A population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatr. Res. 2019, 86, 522–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.A.; Kounali, D.; Cannon, M.; David, A.S.; Fletcher, P.C.; Holmans, P.; Zammit, S. A population-based cohort study examining the incidence and impact of psychotic experiences from childhood to adulthood, and prediction of psychotic disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 2020, 177, 308–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrick, M.T.; Ford, D.C.; Ports, K.A.; Guinn, A.S. Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences from the 2011–2014 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System in 23 States. JAMA Pediatr. 2018, 172, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowker, J.C.; Etkin, R.G. Evaluating the psychological concomitants of othersex crush experiences during early adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 846–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, A.; Heron, J.; Barter, C.; Szilassy, E.; Barnes, M.; Howe, L.D.; Feder, G.; Fraser, A. Risk factors for intimate partner violence and abuse among adolescents and young adults: Findings from a UK population-based cohort. Wellcome Open Res. 2021, 5, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Jiménez, V.; Ortega Rivera, F.J.; Ortega Ruiz, R.; Viejo Almanzor, C. Las relaciones sentimentales en la adolescencia: Satisfacción, conflictos y violencia. Psychol. Writ. 2008, 2, 97–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, S.F.; Fremouw, W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001, 21, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohman, B.J.; Neppl, T.K.; Senia, J.M.; Schofield, T.J. Understanding adolescent and family influences on intimate partner psychological violence during emerging adulthood and adulthood. J. Youth Adolesc. 2013, 42, 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A. Dating violence. In Encyclopedia of School Crime and Violence; Finley, L.L., Ed.; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2011; Volume 1, pp. 128–130. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi, D.M.; Kim, H.K.; Shortt, J.W. Women’s involvement in aggression in young adult romantic relationships: A developmental systems model. In Aggression, Antisocial Behavior, and Violence among Girls: A Developmental Perspective; Putallez, M.M., Bierman, K.L., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004; pp. 223–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shorey, R.C.; Cornelius, T.L.; Bell, K.M. A critical review of theoretical frameworks for dating violence: Comparing the dating and marital fields. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014, 13, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, N.; Oliffe, J.L.; Bungay, V.; Kelly, M.T. Male perpetration of adolescent dating violence: A scoping review. Am. J. Men. Health 2020, 14, 1557988320963600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afrouz, R. The nature, patterns and consequences of technology-facilitated domestic abuse: A scoping review. Trauma Violence Abus. 2021, 28, 15248380211046752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Straus, S.E. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niolon, P.H.; Kearns, M.; Dills, J.; Rambo, K.; Irving, S.; Armstead, T.; Gilbert, L. Preventing Intimate Partner Violence across the Lifespan: A Technical Package of Programs, Policies, and Practices; National Centre for Injury Prevention and Control, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Greenman, S.J.; Matsuda, M. From early dating violence to adult intimate partner violence: Continuity and sources of resilience in adulthood. Crim. Behav. Ment. Health 2016, 26, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmakis, K.A.; Chandler, G.E. Adverse childhood experiences: Towards a clear conceptual meaning. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 1489–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, E.C.; Baerresen, K.; Hokoda, A. Fear as a mediator for the relationship between child sexual abuse and victimization of relationship violence. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2009, 18, 872–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voith, L.A.; Anderson, R.E.; Cahill, S.P. Extending the ACEs framework: Examining the relations between childhood abuse and later victimization and perpetration with college men. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 3487–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrad, J. Health Sciences Literature Review Made Easy. The Matrix Method, 5th ed.; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Burlington, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The conflict tactics (CT) scales. J. Marriage Fam. 1979, 41, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Douglas, E.M. A short form of the Revised Conflict Tactics Scales, and typologies for severity and mutuality. Violence Victims 2004, 19, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Boney-McCoy, S.U.E.; Sugarman, D.B. The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2) development and preliminary psychometric data. J. Fam. Issues 1996, 17, 283–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watkins, L.E.; Maldonado, R.C.; DiLillo, D. The cyber aggression in relationships scale: A new multidimensional measure of technology-based intimate partner aggression. Assessment 2018, 25, 608–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, L.A.; Tolman, R.M.; Ward, L.M. Gender matters: Experiences and consequences of digital dating abuse victimization in adolescent dating relationships. J. Adolesc. 2017, 59, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrajo, E.; Gámez-Guadix, M.; Calvete, E. Cyber dating abuse: Prevalence, context, and relationship with offline dating aggression. Psychol. Rep. 2015, 116, 565–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamby, S. The Partner Cyber Abuse Questionnaire: Preliminary Psychometrics of Technology-Based Intimate Partner Violence; Annual Convention of the Southeastern Psychological Association: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Straus, M.A.; Hamby, S.L.; Finkelhor, D.; Moore, D.W.; Runyan, D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abus. Negl. 1998, 22, 249–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, J.L.; VanDeusen, K.M. The relationship between family of origin violence and dating violence in college men. J. Interpers. Violence 2002, 17, 630–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.H.; White, J.W.; Holland, L.J. A longitudinal perspective on dating violence among adolescent and college-age women. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1104–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.; Gidycz, C.A. A prospective analysis of the relationship between childhood sexual victimization and perpetration of dating violence and sexual assault in adulthood. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 21, 732–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, R.; Gidycz, C.A. Dating violence among college men and women: Evaluation of a theoretical model. J. Interpers. Violence 2006, 21, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, K.M.; Desai, A.D.; Gidycz, C.A.; Vanwynsberghe, A. College women’s aggression in relationships: The role of childhood and adolescent victimization. Psychol. Women Q. 2009, 33, 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milletich, R.J.; Kelley, M.L.; Doane, A.N.; Pearson, M.R. Exposure to interparental violence and childhood physical and emotional abuse as related to physical aggression in undergraduate dating relationships. J. Fam. Violence 2010, 25, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gover, A.R.; Jennings, W.G.; Tomsich, E.A.; Park, M.; Rennison, C.M. The influence of childhood maltreatment and self-control on dating violence: A comparison of college students in the United States and South Korea. Violence Victims 2011, 26, 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Breslau, J.; Chung, W.J.; Green, J.G.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Kessler, R.C. Adverse childhood experiences and risk of physical violence in adolescent dating relationships. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2011, 65, 1006–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, K.A.; Brownridge, D.A.; Melander, L.A. The effect of poor parenting on male and female dating violence perpetration and victimization. Violence Victims 2011, 26, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dardis, C.M.; Edwards, K.M.; Kelley, E.L.; Gidycz, C.A. Dating violence perpetration: The predictive roles of maternally versus paternally perpetrated childhood abuse and subsequent dating violence attitudes and behaviors. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2013, 22, 6–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, W.G.; Park, M.; Richards, T.N.; Tomsich, E.; Gover, A.; Powers, R.A. Exploring the relationship between child physical abuse and adult dating violence using a causal inference approach in an emerging adult population in South Korea. Child Abus. Negl. 2014, 38, 1902–1913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, M.; Reese-Weber, M.; Kahn, J.H. Exposure to family violence and attachment styles as predictors of dating violence perpetration among men and women: A mediational model. J. Interpers. Violence 2014, 29, 20–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, W.G.; Richards, T.N.; Tomsich, E.; Gover, A.R. Investigating the role of child sexual abuse in intimate partner violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood from a propensity score matching approach. J. Child Sex. Abus. 2015, 24, 659–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abajobir, A.A.; Kisely, S.; Williams, G.M.; Clavarino, A.M.; Najman, J.M. Substantiated childhood maltreatment and intimate partner violence victimization in young adulthood: A birth cohort study. J. Youth Adolesc. 2017, 46, 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cale, J.; Tzoumakis, S.; Leclerc, B.; Breckenridge, J. Patterns of Intimate Partner Violence victimization among Australia and New Zealand female university students: An initial examination of child maltreatment and self-reported depressive symptoms across profiles. Aust. J. Criminol. 2017, 50, 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.A.; Schmitz, R.M.; Ray, C.M.; Simons, L.G. The role of entitlement, self-control, and risk behaviors on dating violence perpetration. Violence Victims 2017, 32, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kalaitzaki, A.E. The pathway from family violence to dating violence in college students’ relationships: A multivariate model. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 313–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnakumar, A.; Conroy, N.; Narine, L. Correlates of sex-specific young adult college student dating violence typologies: A latent class analysis approach. Psychol. Violence 2018, 8, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, L.A.; van Dellen, M.; Shaffer, A. Childhood emotional maltreatment and psychological aggression in young adult dating relationships: The moderating role of emotion communication. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 36, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Y.F.; Markham, C. The roles of family factors and relationship dynamics on dating violence victimization and perpetration among college men and women in emerging adulthood. J. Interpers. Violence 2019, 34, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tussey, B.E.; Tyler, K.A. Toward a comprehensive model of physical dating violence perpetration and victimization. Violence Victims 2019, 34, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Gonzalez, I.; Charak, R.; Gilbar, O.; Viñas-Racionero, R.; Strait, M.K. Witnessing parental violence and cyber IPV perpetration in Hispanic emerging adults: The mediating role of attitudes toward IPV. J. Interpers. Violence 2022, 37, NP8115–NP8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascardi, M.; Jouriles, E.N.; Temple, J.R. Distinct and overlapping correlates of psychological and physical partner violence perpetration. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 2375–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, M.M.; Parmenter, M. Childhood trauma, trait anxiety, and anxious attachment as predictors of intimate partner violence in college students. J. Interpers. Violence 2020, 35, 6067–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baller, S.L.; Lewis, K. Adverse Childhood Experiences, Intimate Partner Violence, and Communication Quality in a College-Aged Sample. J. Fam. Issues 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celsi, L.; Paleari, F.G.; Fincham, F.D. Adverse childhood experiences and early maladaptive schemas as predictors of cyber dating abuse: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model approach. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikulina, V.; Gelin, M.; Zwilling, A. Is there a cumulative association between adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence in emerging adulthood? J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP1205–NP1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.C.; Miller, K.F.; Moss, I.K.; Margolin, G. Perspective-taking and empathy mitigate family-of-origin risk for electronic aggression perpetration toward dating partners: A brief report. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, NP1155–NP1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tussey, B.E.; Tyler, K.A.; Simons, L.G. Poor parenting, attachment style, and dating violence perpetration among college students. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 2097–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, C.; Cunradi, C.B.; Todd, M. Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence: Testing psychosocial mediational pathways among couples. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012, 22, 832–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widom, C.S.; Wilson, H.W. Intergenerational Transmission of Violence. In Violence and Mental Health; Lindert, J., Levav, I., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Walters, R.H. Social Learning Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Marek, E.N.; Cafferky, B.; Dharnidharka, P.; Mallory, A.B.; Dominguez, M.; High, J.; Stith, S.M.; Mendez, M. Effects of childhood experiences of family violence on adult partner violence: A meta-analytic review. J. Fam. Theor. Rev. 2015, 7, 498–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haselschwerdt, M.L.; Savasuk-Luxton, R.; Hlavaty, K. A methodological review and critique of the “intergenerational transmission of violence” literature. Trauma Violence Abus. 2019, 20, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonu, S.; Post, S.; Feinglass, J. Adverse childhood experiences and the onset of chronic disease in young adulthood. Prev. Med. 2019, 123, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganson, K.T.; Jackson, D.B.; Testa, A.; Nagata, J.M. Performance-enhancing substance use and intimate partner violence: A prospective cohort study. J. Interpers. Violence 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, P.C.; Copp, J.E.; Manning, W.D.; Longmore, M.A. When worlds collide: Linking involvement with friends and intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Soc. Forces 2020, 98, 1196–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graves, K.N.; Sechrist, S.M.; White, J.W.; Paradise, M.J. Intimate partner violence perpetrated by college women within the context of a history of victimization. Psychol. Women Q. 2005, 29, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Terms |

|---|

| 1. (“adult*” OR “young adult*” OR “emerging adult*” OR “early adult*” OR “18 yrs & older”).ti |

| 2. (“dating violen*” OR “dating abus*” OR “dating aggress*” OR “cyber dating violen*” OR “cyber dating abus*” OR “cyber dating aggress*” OR “digital dating abus* OR “digital dating violen*” OR “digital dating aggress*” OR “electronic dating abus*” OR “electronic dating violen*” OR electronic dating aggress*” OR “intimate partner violen*” OR “intimate partner abus*”).ti |

| 3. (victim* OR perpetrat* OR aggress*).ti |

| 4. (“Adverse Childhood Experienc*” OR “ACEs” OR “advers*” OR “childhood neglect“ OR “childhood psychological abus*” OR “childhood sexual abus*” OR “childhood physical abus*” OR “exposure to substance abus*” OR “substance abus*” OR “exposure to mental illness” OR “parental mental illness” OR “mother treated violen*” OR “parental substance abus*” OR “criminal behavior in household” OR “sibling violen*” OR “family economic adversity” |

| 5. (associat* OR correlat* OR mediat* OR moderat* OR determinant* OR predict*).ti |

| 6. 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and 5 search performed in each database. |

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| Participants aged 18 years or older. | Participants under 18 years of age. |

| Participants in the study had to belong to general populations. | Clinical samples or subgroups. For example, people with mental illness, federal sex offenders. |

| Quantitative empirical research, published in peer-reviewed journals. | Qualitative research, articles describing interventions or prevention and intervention programs, literature reviews, systematic reviews, conference papers, doctoral theses, journal articles. |

| Research investigating experiences of both in-person and online violence in dating relationships. | Research investigating both in-person and online forms of violence occurring outside of dating relationships such as among married or cohabiting couples, etc. |

| Research investigating at least one of the experiences linked to “adverse childhood experiences” within the family context. | Research not investigating at least one of the experiences linked to “adverse childhood experiences” within the family context. |

| Published in English. | Published in languages other than English. |

| Study | Study Aim | Study Design | Study Selection | Selection Bias 1 | Representative Sample | Stat Power | Response Rate | Measure Validity | Stat Sig | Confidence Interval | Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [50] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [51] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [52] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [53] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [54] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [39] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [55] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [56] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [57] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| [58] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 8 |

| [59] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [60] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| [61] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| [62] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| [63] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 7 |

| [64] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| [65] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| [66] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [67] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 7 |

| [68] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [69] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 8 |

| [70] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | 6 |

| [71] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| [72] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [73] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [40] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [74] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [75] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [24] | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 9 |

| [76] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | Yes | 6 |

| [77] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

| [78] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unsure | No | Unsure | Yes | Yes | No | 5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Navarro, R.; Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S.; Víllora, B. Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060162

Navarro R, Larrañaga E, Yubero S, Víllora B. Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(6):162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060162

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavarro, Raúl, Elisa Larrañaga, Santiago Yubero, and Beatriz Víllora. 2022. "Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 6: 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060162

APA StyleNavarro, R., Larrañaga, E., Yubero, S., & Víllora, B. (2022). Associations between Adverse Childhood Experiences within the Family Context and In-Person and Online Dating Violence in Adulthood: A Scoping Review. Behavioral Sciences, 12(6), 162. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12060162