Does Value Lead to Loyalty? Exploring the Important Role of the Tourist–Destination Relationship

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Tourist Loyalty and Perceived Value

2.2. Tourist–Destination Relationship

2.3. Hypothesis Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Measures

3.2. Study Site and Data Collection

4. Data Analysis

4.1. Preliminary Analysis

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Analysis

4.2.1. Measurement Model Assessment

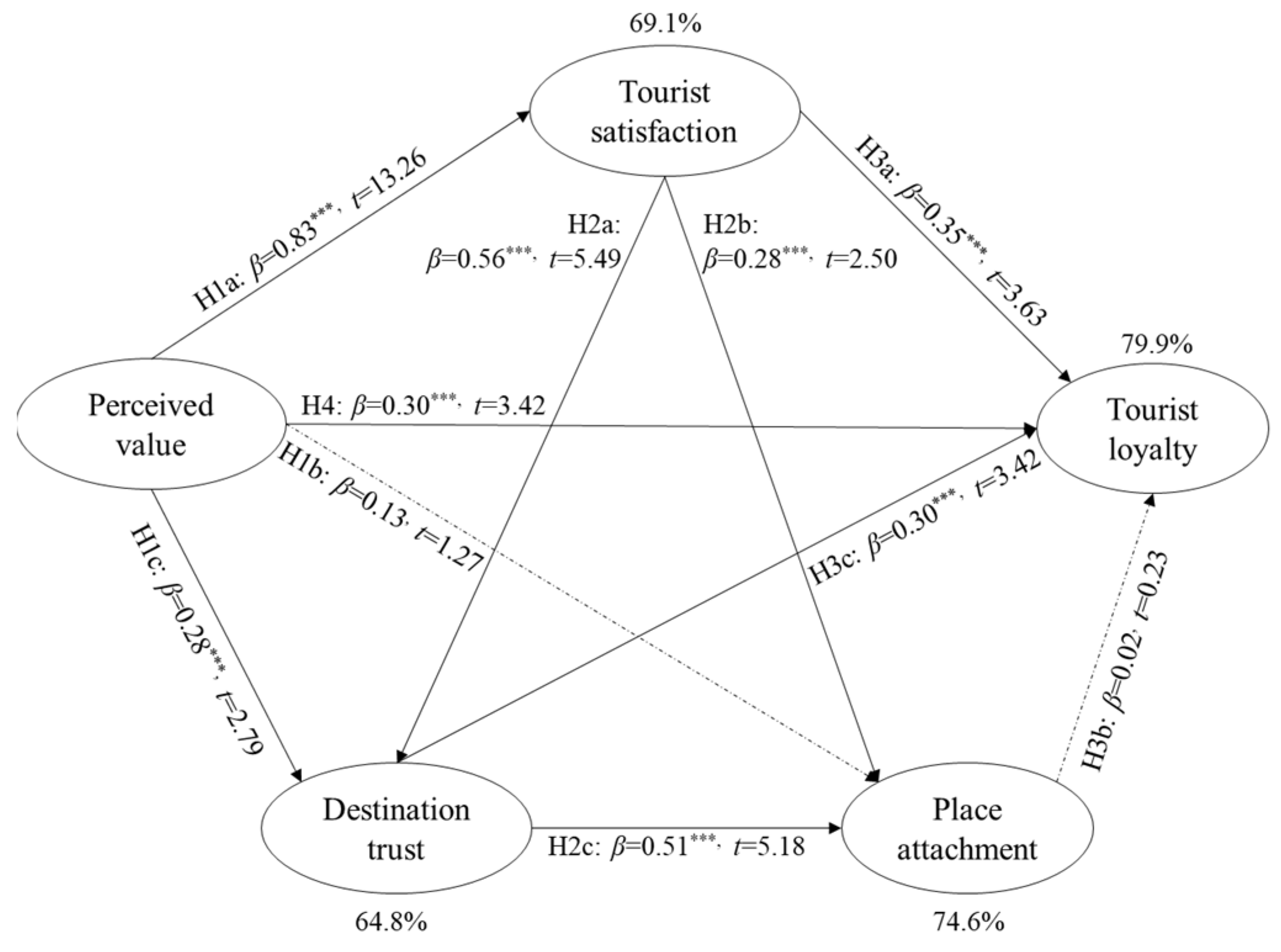

4.2.2. Structural Model Assessment

5. Discussion and Implications

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Implications

6. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roodurmun, J.; Juwaheer, T.D. Influence of trust on destination loyalty—An empirical analysis-the discussion of the research approach. Int. Res. Symp. Serv. Manag. 2010, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson, P.G.; Spreng, R.A. Modelling the relationship between perceived value, satisfaction and repurchase intentions in a business-to-business, services context: An empirical examination. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 414–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J. Revitalizing relationship marketing. J. Serv. Mark. 2017, 31, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, N.; Lee, H.; Lee, S. Event Quality, Perceived Value, Destination Image, and Behavioral Intention of Sports Events: The Case of the IAAF World Championship, Daegu, 2011. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2013, 18, 849–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Phou, S. A closer look at destination: Image, personality, relationship, and loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 269–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Tourism destination loyalty. J. Travel Res. 2000, 39, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Li, T. A review about the loyalty of tourists in tourism destination overseas in the past decade. Tour. Trib. 2010, 25, 86–94. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tasci, A.D.; Uslu, A.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Place-Oriented or People-Oriented Concepts for Destination Loyalty: Destination Image and Place Attachment versus Perceived Distances and Emotional Solidarity. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lv, X.; Scott, M. Understanding the dynamics of destination loyalty: A longitudinal investigation into the drivers of revisit intentions. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cossío-Silva, F.J.; Revilla-Camacho, M.Á.; Vega-Vázquez, M. The tourist loyalty index: A new indicator for measuring tourist destination loyalty? J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, S.J.; Crompton, J.L. The usefulness of selected variables for predicting activity loyalty. Leis. Sci. 1991, 13, 205–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoemaker, S.; Lewis, R.C. Customer loyalty: The future of hospitality marketing. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 1999, 18, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S.T.; Scott, D. Examining the mediating role of experience quality in a model of tourist experiences. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2004, 16, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P.E.; Pritchard, M.; Smith, B. The destination product and its impact on traveler perceptions. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapito, D.; Valle, P.; Mendes, J. The sensory dimension of tourist experiences: Capturing meaningful sensory-informed themes in Southwest Portugal. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, Y. Study on the Impact of Brand Equity and Brand Relationship on Customer Repurchase Behavior in Economic Hotel. Master’s Thesis, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Esch, F.R.; Langner, T.; Schmitt, B.H.; Geus, P. Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2006, 15, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blackston, M. Observations: Building brand equity by managing the brand’s relationships. J. Advert. Res. 1992, 32, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz, A.M.; O’Guinn, T.C. Brand community. J. Consum. Res. 2001, 27, 412–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekinci, Y. From destination image to destination branding: An emerging area of research. e-Rev. Tour. Res. 2003, 1, 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- DeBenedetti, A.; Oppewal, H.; Zeynep, A. Place attachment in commercial settings: A gift economy perspective. Adv. Consum. Res. 2014, 40, 904–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, X. From “people-brand” Relationship to “people-destination” relationship: The effects of self-destination connection. Tour. Trib. 2015, 30, 52–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, V. Examining the role of destination personality and self-congruity in predicting tourist behavior. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2016, 20, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A.; Han, H. Role of halal-friendly destination performances, value, satisfaction, and trust in generating destination image and loyalty. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2019, 13, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hyun, S.S. Customer retention in the medical tourism industry: Impact of quality, satisfaction, trust, and price reasonableness. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, T.; Li, M.Y. A study of behavioral intentions, patient satisfaction, perceived value, patient trust and experiential quality for medical tourists. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2016, 17, 114–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhen, Y. The influence of tourists’ motivation and perceived value on their satisfaction and willingness to act in “foreign caravanserai”. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Sci. Ed.) 2018, 45, 92–102. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.F.; Chen, F.S. Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandža Bajs, I. Tourist perceived value, relationship to satisfaction, and behavioral intentions. J. Travel Res. 2013, 54, 122–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Li, X. Brand emotional attachment and brand trust: Moderating effect based on brand familiarity. Ind. Eng. Manag. 2018, 23, 186–193. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationship. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, A.; Huang, F.; Li, W. Empirical research on the key driving factors of revisiting intention: A comparison of perceived value, perceived attraction, tourist satisfaction and tourist trust. J. Jiangxi Univ. Financ. Econ. 2013, 85, 38–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Lin, D. Research on trust-based word-of-mouth recommendation mechanism of tourism destinations. Tour. Trib. 2018, 33, 63–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Q. Research on the Influence of Tourist Destination Brand Experience on Tourist Loyalty. Master’s Thesis, Hunan Normal University, Changsha, China, 2016. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Delgado-Ballester, E.; Luis Munuera-Alemán, J. Brand trust in the context of consumer loyalty. Eur. J. Market. 2001, 35, 1238–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.C.; González, F.J.M. The importance of quality, satisfaction, trust, and image in relation to rural tourist loyalty. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 117–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Back, B.J. Attendee-based brand equity. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, H.Y.; Perks, H. Effects of consumer perceptions of brand experience on the web: Brand familiarity, satisfaction, and brand trust. J. Consum. Behav. 2005, 4, 438–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Moon, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Yi, M.Y. Antecedents, and consequences of mobile phone usability: Linking simplicity and interactivity to satisfaction, trust, and brand loyalty. Inf. Manag. 2015, 52, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; McInnis, D.; Park, W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachment to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpenny, E. Environmental Behavior, Place Attachment and Park Visitation: A Case Study of Visitors to Point Pelee National Park. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada, 2006. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Zenker, S.; Rütter, N. Is satisfaction the key? The role of citizen satisfaction, place attachment and place brand attitude on positive citizenship behavior. Cities 2014, 38, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Dwyer, L.; Firth, T. Effect of dimensions of place attachment on residents’ word-of-mouth behavior. Tour. Geogr. 2014, 16, 826–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Mavondo, F.T. The satisfaction-place attachment relationship: Potential mediators and moderators. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2593–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Lin, D. Tourists’ service perception, place attachment and loyalty: A case study of Xiamen. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 390–400. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.J.; Wu, C.; Yuan, J. Exploring visitors’ experiences and intention to revisit a heritage destination: The case of Lukang, Taiwan. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2010, 11, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Smith, L.D.G.; Weiler, B. Relationships between place attachment, place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviour in an Australian national park. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 434–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.C. The impacts of brand experiences on brand loyalty: Mediators of brand love and trust. Manag. Decis. 2017, 55, 915–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F.; Bilim, Y. Destination attachment: Effects on customer satisfaction and cognitive, affective, and conative loyalty. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, L.L. Relationship marketing of services-growing interest, emerging perspective. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 1995, 23, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peña, A.I.P.; Jamilena, D.M.F.; Molina, M.Á.R. The perceived value of the rural tourism stay and its effect on rural tourist behavior. J. Sustain. Tour. 2012, 20, 1045–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 1st ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 58–65. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. Structural Equation Modeling with EQS, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 134–138. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 328–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baloglu, S. An empirical investigation of attitude theory for tourist destinations: A comparison of visitors and nonvisitors. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 1998, 22, 211–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S.; Ryan, C. Destination positioning analysis through a comparison of cognitive, affective, and conative perceptions. J. Travel Res. 2004, 42, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, H.; Cao, N.; Li, Z.; He, Y. Research on influencing factors of farmers’ entrepreneurial performance in rural tourism industry. J. Liaoning Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 47, 70–80. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Morar, C.; Tiba, A.; Basarin, B.; Vujičić, M.; Valjarević, A.; Niemets, L.; Gessert, A.; Jovanovic, T.; Drugas, M.; Grama, V.; et al. Predictors of Changes in Travel Behavior during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Role of Tourists’ Personalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Description | Standardized Loading | t-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived value (coded as PV) | |||

| PV1 | Traveling to Hangzhou is worth the price. | 0.85 | - |

| PV2 | Compared to other destinations, traveling to Hangzhou is a good deal. | 0.78 | 13.62 |

| PV3 | Traveling to Hangzhou offers good value for money. | 0.86 | 16.00 |

| PV4 | Traveling to Hangzhou meets my travel needs. | 0.88 | 16.60 |

| Tourist satisfaction (coded as TS) | |||

| TS1 | I am happy about my decision to stay in Hangzhou | 0.90 | - |

| TS2 | I believe I did the right thing when I chose to make my holiday in Hangzhou | 0.94 | 22.81 |

| TS3 | Overall, I am satisfied with the decision to make my holiday in Hangzhou | 0.94 | 22.87 |

| Place attachment (coded as PA) | |||

| PA1 | Hangzhou means a lot to me. | 0.72 | - |

| PA2 | I am very attached to Hangzhou. | 0.78 | 10.80 |

| PA3 | For the activities that I enjoy most, the settings and facilities provided by Hangzhou are the best. | 0.62 | 8.55 |

| PA4 | For what I like to do, I could not imagine anything better than the settings and facilities provided by Hangzhou. | 0.80 | 11.08 |

| Destination trust (coded as DT) | |||

| DT1 | Hangzhou guarantees tourist satisfaction. | 0.85 | - |

| DT2 | Hangzhou is a destination that never disappoints me. | 0.87 | 16.88 |

| DT3 | Hangzhou would compensate me in some ways for the problems with the trip. | 0.80 | 14.68 |

| DT4 | Hangzhou would make any effort to satisfy tourists. | 0.83 | 15.35 |

| DT5 | Hangzhou would be honest and sincere in addressing my concerns. | 0.83 | 15.57 |

| Tourist loyalty (coded as TL) | |||

| TL1 | I am willing to revisit Hangzhou in the near future. | 0.74 | - |

| TL2 | I intend to visit Hangzhou again in the near future. | 0.80 | 12.11 |

| TL3 | I am willing to recommend other people to visit Hangzhou. | 0.92 | 14.07 |

| TL4 | I will say positive things to other people about Hangzhou as a tourist destination. | 0.90 | 13.70 |

| Variable | Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 54 | 24.55 |

| Female | 166 | 75.45 | |

| Age | 18–25 | 96 | 43.64 |

| 26–35 | 92 | 41.82 | |

| 36–45 | 30 | 13.64 | |

| 46–55 | 2 | 0.91 | |

| 55 and above | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Education status | Primary school and below | 0 | 0.00 |

| Junior School | 1 | 0.45 | |

| High School/Technical secondary school | 9 | 4.09 | |

| Junior college/Higher vocational college | 17 | 7.73 | |

| Undergraduate college | 137 | 62.27 | |

| Postgraduate and above | 56 | 25.45 | |

| Monthly income | Under 2000 | 87 | 39.55 |

| (RMB) | 2001–5000 | 54 | 24.55 |

| 5001–8000 | 46 | 20.91 | |

| 8001–10,000 | 19 | 8.64 | |

| 10,001 and above | 14 | 6.36 |

| CR | AVE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PV | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.84 | ||||

| 2. TS | 0.95 | 0.85 | 0.83 | 0.92 | |||

| 3. PA | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.73 | ||

| 4. DT | 0.91 | 0.71 | 0.74 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.84 | |

| 5. TL | 0.92 | 0.70 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.84 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Coefficient | t-Value | p | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: | Perceived value → Tourist satisfaction | 0.83 | 13.26 | 0.00 | Supported |

| H1b: | Perceived value → Place attachment | 0.13 | 1.27 | 0.20 | Not Supported |

| H1c: | Perceived value → Destination trust | 0.28 | 2.79 | 0.01 | Supported |

| H2a: | Tourist satisfaction → Destination trust | 0.56 | 5.49 | 0.00 | Supported |

| H2b: | Tourist satisfaction → Place attachment | 0.28 | 2.50 | 0.01 | Supported |

| H2c: | Destination trust → Place attachment | 0.51 | 5.18 | 0.00 | Supported |

| H3a: | Tourist satisfaction → Tourist loyalty | 0.35 | 3.63 | 0.00 | Supported |

| H3b: | Place attachment → Tourist loyalty | 0.02 | 0.23 | 0.82 | Not Supported |

| H3c: | Destination trust → Tourist loyalty | 0.30 | 3.20 | 0.00 | Supported |

| H4: | Perceived value → Tourist loyalty | 0.30 | 3.42 | 0.00 | Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; He, W. Does Value Lead to Loyalty? Exploring the Important Role of the Tourist–Destination Relationship. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050136

Wang H, Yang Y, He W. Does Value Lead to Loyalty? Exploring the Important Role of the Tourist–Destination Relationship. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(5):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050136

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haihong, Yufan Yang, and Wenjun He. 2022. "Does Value Lead to Loyalty? Exploring the Important Role of the Tourist–Destination Relationship" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 5: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050136

APA StyleWang, H., Yang, Y., & He, W. (2022). Does Value Lead to Loyalty? Exploring the Important Role of the Tourist–Destination Relationship. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050136