English-Learning Motivation among Chinese Mature Learners: A Comparative Study of English and Non-English Majors

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What are the motivation types exhibited by English and non-English majors among mature learners?

- (2)

- What factors motivate English and non-English majors to learn English?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Motivation for English Language Learning

2.2. Motivation of Mature English Learners

2.3. Mature English Learners in China

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instruments

3.3. Data Analysis

3.3.1. Content Analysis

3.3.2. Text Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Motivation Types of English Majors

Participant B: ‘I find learning English a lot of fun. Meanwhile, good language ability to some extent brings me higher salary and is also the requirement of my current job.’

Participant H: ‘I work hard to learn English not only because of interest or job demands but also for a higher salary to accomplish my desire of studying abroad.’

Participant I: ‘I like English and I have been working hard for a job promotion that can provide an opportunity to work abroad. This is a good way for me to experience foreign culture and integrate into local life.’

Participant J: ‘A better understanding of my foreign customers’ culture and good English proficiency are preconditions for improved communication. Additionally, I work hard to secure my expenses for going abroad to experience life in an English-speaking country.’

4.2. Motivation Types of Non-English Majors

Participant A: ‘I am forced to learn English to better communicate with my foreign customers. I also hope to get an opportunity for job promotion by obtaining an English certificate.’

Participant C: ‘Learning English is torture for me, but I have to learn it since my salary is closely related to the amount of goods I sell to those foreign customers.’

Participant D: ‘I work hard to improve my English ability in order to be qualified for the position of the overseas sales manager.’

Participant E: ‘I have to improve my English language ability so as to deal with lots of overseas orders written in English without mistakes.’

Participant F: ‘I’m learning English in preparation for finding a job, because people with good English competency are more likely to get a higher salary.’

Participant G: ‘I am made to learn English since I need to introduce our products in English to customers around the world in each year’s international products fair.’

Participant D: ‘I had no interest in English at first; I found it interesting after frequent contact with my foreign customers, and gradually had an idea of integrating into the community for further communication.’

Participant E: ‘My foreign customers make me find that English learning is not as boring as I thought before. I really enjoy [discussing] the people, culture, and life in their countries.’

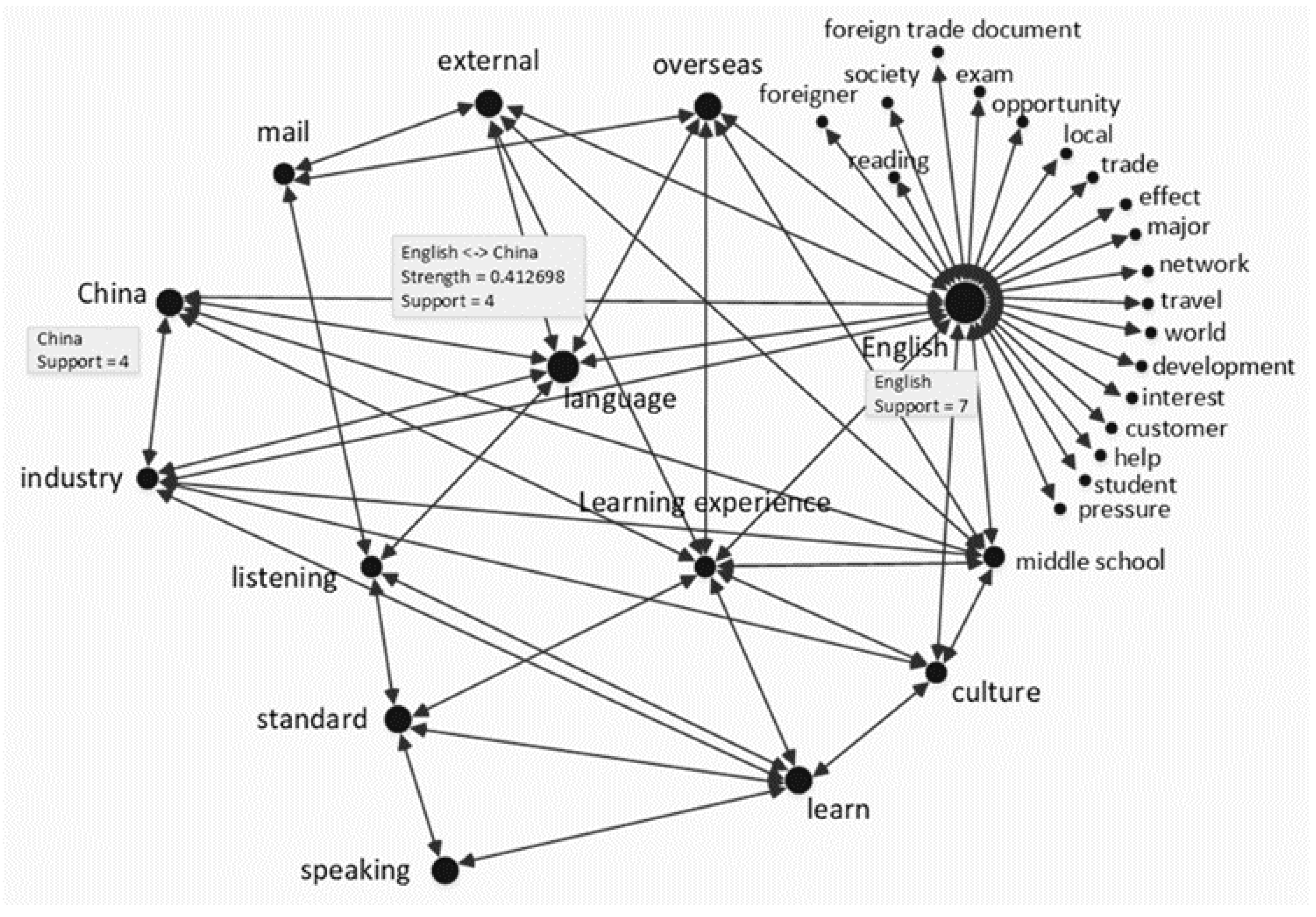

4.3. Social Network Analysis of Factors Influencing English Majors’ Motivation

Participant J: ‘The globalization brings both opportunities and challenges for us. Good English language competence will enhance our competitive power in the workplace. Meanwhile, companies demand greater English proficiency.’

Participant I: ‘My middle school English teacher made me interested in learning English. He would always design a lot of games to [create an] active classroom atmosphere.’

Participant H: ‘The way we express ourselves is quite different from that of Westerners, [because of] our different cultural contexts. I think a good cultural understanding can facilitate our language learning.’

Participant B: ‘My daily work is mainly to communicate with foreign customers through e-mail. At weekends, I watch some English movies, listen to English songs, and do overseas online shopping. Additionally, I travel abroad sometimes... English has penetrated into each aspect of my daily work and life.’

4.4. Social Network Analysis of Factors Influencing Non-English Majors’ Motivation

Participant E: ‘I found learning English was boring since my middle school English teacher just repeated the content of the textbook. Currently … teaching in adult education is also a perfunctory action.’

Participant C: ‘I came here in the hope [of obtaining] more practical knowledge on foreign trade, but [the teaching] has not lived up to my expectations. As far as I know, the teachers here are part-time teachers hired from the universities; they don’t care about our learning achievements.’

Participant A: ‘I accumulate a number of new words by searching for their meanings in the electronic dictionary; and I often use keywords to communicate with customers in my daily work since people can understand the sentence if they know the meaning of the keywords.’

5. Discussion

5.1. Motivation Types of English and Non-English Majors among Mature Learners

5.2. Factors Influencing English and Non-English Majors to Learn English

5.3. Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Direction

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dörnyei, Z. Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Lang. Teach. 1998, 31, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wlodkowskib, R.J. Enhancing Adult Motivation to Learn: A Comprehensive Guide for Teaching all Adults; Raymond, J.W., Ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.F.; Li, Y.W. Analysis of adult foreign language learning motivation and study of training market development. J. Hebei Uni. Eng. 2009, 26, 102–103. [Google Scholar]

- Carré, P. Motivation in adult education: From engagement to performance. In Proceedings of the Adult Education Research, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–7 June 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Pires, A.L.S. Higher education and adult motivation towards lifelong learning: An empirical analysis of university post-gradates perspectives. Euro. J. Voca. Train. 2009, 46, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Rothes, A.; Lemos, M.S.; Gonçalves, T. Motivational profiles of adult learners. Adu. Educ. Quar. 2017, 67, 3–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, H.; Roopchand, N. Intrinsic motivation and self-esteem in traditional and mature students at a post-1992 university in the north-east of England. Educ. Stud. 2003, 29, 243–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuetze, H.G.; Slowey, M. Participation and exclusion: A comparative analysis of non-traditional students and lifelong learners in higher education. High. Educ. 2002, 44, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubackova, S.; Semradova, I. Research study on motivation in adult education. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 159, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Huang, W. An exploration of foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Educ. Res. Int. 2011, 2011, 493167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, X. An investigation of Chinese university students’ foreign language anxiety and English learning motivation. Eng. Ling. Res. 2013, 2, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xu, S.; Yang, X. A Survey and quantitative analysis of Chinese students’ English learning motivation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education, Management, Commerce and Society (EMCS-15), Copenhagen, Denmark, 22–24 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.L.; Zhang, D.B. Reflection on the research on the development of adult education in the recent decade. Adult Educ. 2012, 1, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.C. Social Psychology and Second Language Learning: The Role of Attitude and Motivation; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, T.A. Integrative motivation as a predictor of achievement in the foreign language classroom. Appl. Lang. Learn. 2008, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Y.C.; Ganapathy, M. To investigate ESL students’ instrumental and integrative motivation towards English language learning in a Chinese school in Penang: Case study. Engl. Lang. Teach. 2017, 10, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, R.; Dörnyei, Z.; Noels, K.A. Motivation, self-confidence, and group cohesion in the foreign language classroom. Lang. Learn. 1994, 44, 417–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol. Inq. 2000, 11, 227–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. Self-determination theory: A dialectical Framework for understanding sociocultural influences student motivation. Big Theor. Rev. 2004, 4, 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, W.; Bruinsma, M. A structural model of self-concept, autonomous motivation and academic performance in cross-cultural perspective. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2006, 4, 551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Alivernini, F.; Lucidi, F. Relationship between social context, self-efficacy, motivation, academic achievement, and intention to drop out of high school: A longitudinal study. J. Educ. Res. 2011, 104, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lens, W.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Matos, L. Motivation: Quantity and quality matter. In Closer to Emotions III; Blachnio, A., Przepiorka, A., Eds.; Wydawnictwo KUL: Lublin, Poland, 2009; pp. 111–135. [Google Scholar]

- Hayamizu, T. Achievement motivation located between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation. Jap. Psychol. Rev. 1995, 38, 171–193. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaka-Carreira, J. New framework of intrinsic/extrinsic and integrative/instrumental motivation in second language acquisition. Keiai J. Int. Stud. 2005, 16, 39–64. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Oliemat, A. Motivation and attitudes towards learning English among Saudi female English majors at Dammam University. Int. J. Lang. Lit. 2019, 7, 121–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreira, J.M. Motivation for learning English as a foreign language in Japanese elementary schools. JALT J. 2006, 28, 135–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noels, K.A. Learning Spanish as a second language: Learners’ orientations and perceptions of their teachers’ communication style. Lang. Learn. 2001, 51, 107–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.Q.; Wen, Q.F. The inner structure of learning motivation of non-English majors. For. Lang. Teach. Res. 2002, 34, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Suwannatho, N.; Thepsiri, K. The correlation between low proficiency undergraduate students’ attitudes and motivation. In Proceedings of the 35th Thailand TESOL International Conference “English Language Education in Asia: Reflections and Directions, Bangkok, Thailand, 29–31 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bong, M.; Skaalvik, E.M. Academic self-concept and self-efficacy: How different are they really? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2003, 15, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A. Open university/distance learners’ academic self-concept and academic performance. J. Distance Educ. 2001, 8, 133–146. [Google Scholar]

- Vallerand, R.J.; Pelletier, L.G.; Blais, M.R.; Brière, N.M.; Senecal, C.; Vallières, É.F. On the assessment of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education: Evidence on the concurrent and construct validity of the Academic Motivation Scale. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1993, 53, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Boraie, D.; Kassabgy, O. Foreign language motivation: Internal structure and external connections. In Language Learning Motivation: Pathways to the New Century; Oxford, R.L., Ed.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1996; pp. 14–87. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, S.R. Preferences for instructional activities and motivation: A comparison of student and teacher perspectives. In Motivation and Second Language Acquisition; Dörnyei, Z., Schmidt, R., Eds.; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2001; pp. 185–211. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.K. On the development and innovation of Adult English education. Chi. Adu. Educ. 2015, 2, 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B. Exploring effective management based on the characteristics of adult students. Chi. Adu. Educ. 2005, 9, 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Qaiser, S.; Ali, R. Text mining: Use of TF-IDF to examine the relevance of words to documents. Int. Comp. Appl. 2018, 181, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Motivation Types | Definition |

|---|---|

| Means-autonomy-integrative | Desire for integration into the target language community, with the language only as a means to an end. |

| Means-autonomy-instrumental | Desire for utilitarian gains, with the target language only as a means to an end. |

| Goal-autonomy-integrative | Desire for integration into the target language community and absorption in language learning. |

| Goal-autonomy-instrumental | Desire for utilitarian gains and absorption in language learning. |

| Means-heteronomy-integrative | Target language learning for integrative reasons by external power, with language learning only as a means to an end. |

| Means-heteronomy-instrumental | Target language learning for utilitarian gains by external power, with language learning only as a means to an end. |

| Goal-heteronomy-integrative | Target language learning for integrative reasons by external power with absorption in language learning. |

| Goal-heteronomy-instrumental | Target language learning for utilitarian gains by external power with absorption in language learning. |

| Participants | Gender | Age | Major |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Male | 25 | Logistics Management |

| B | Female | 30 | English |

| C | Male | 29 | Logistics Management |

| D | Male | 26 | Administrative Management |

| E | Female | 27 | Business Management |

| F | Female | 22 | Accounting |

| G | Male | 45 | Art Design |

| H | Female | 38 | English |

| I | Female | 24 | English |

| J | Male | 32 | English |

| Stimuli | Code | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| Personal desire | Individual interest | 4 |

| Studying/Working abroad | 3 | |

| External power | Job requirements | 4 |

| Utilitarian gains | Higher salary | 4 |

| Job promotion | 4 | |

| Integrative reasons | Integrate with target language community | 3 |

| Stimuli | Code | Frequency |

|---|---|---|

| External power | Job requirements | 6 |

| Utilitarian gains | Higher salary | 6 |

| Job promotion | 6 |

| Motivation Types | Participants | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | |

| Means-autonomy-integrative | ||||||||||

| Means-autonomy-instrumental | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Goal-autonomy-integrative | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||||

| Goal-autonomy-instrumental | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Means-heteronomy-integrative | ||||||||||

| Means-heteronomy-instrumental | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Goal-heteronomy-integrative | ||||||||||

| Goal-heteronomy-instrumental | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, Y.; Teo, T.; Wang, T.-H. English-Learning Motivation among Chinese Mature Learners: A Comparative Study of English and Non-English Majors. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050135

Sun Y, Teo T, Wang T-H. English-Learning Motivation among Chinese Mature Learners: A Comparative Study of English and Non-English Majors. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(5):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050135

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Yu, Timothy Teo, and Tzu-Hua Wang. 2022. "English-Learning Motivation among Chinese Mature Learners: A Comparative Study of English and Non-English Majors" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 5: 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050135

APA StyleSun, Y., Teo, T., & Wang, T.-H. (2022). English-Learning Motivation among Chinese Mature Learners: A Comparative Study of English and Non-English Majors. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 135. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050135