Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Framing in Political Contexts

1.2. Moral Foundations Theory

1.2.1. Care/Harm

1.2.2. Fairness/Cheating

1.2.3. Loyalty/Betrayal

1.2.4. Authority/Subversion

1.2.5. Sanctity/Degradation

1.3. Moral Framing to Shape Pro-Refugee Attitudes and Behaviour

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Control Group

2.3. Stimuli

2.4. Measures

2.5. Participants

2.6. Consent

2.7. Sample Size

2.8. Recruitment

2.9. Ethical Considerations

2.10. Procedure

2.11. Exclusion Criteria and Process

2.12. Materials

2.13. Pre-Registration

3. Results

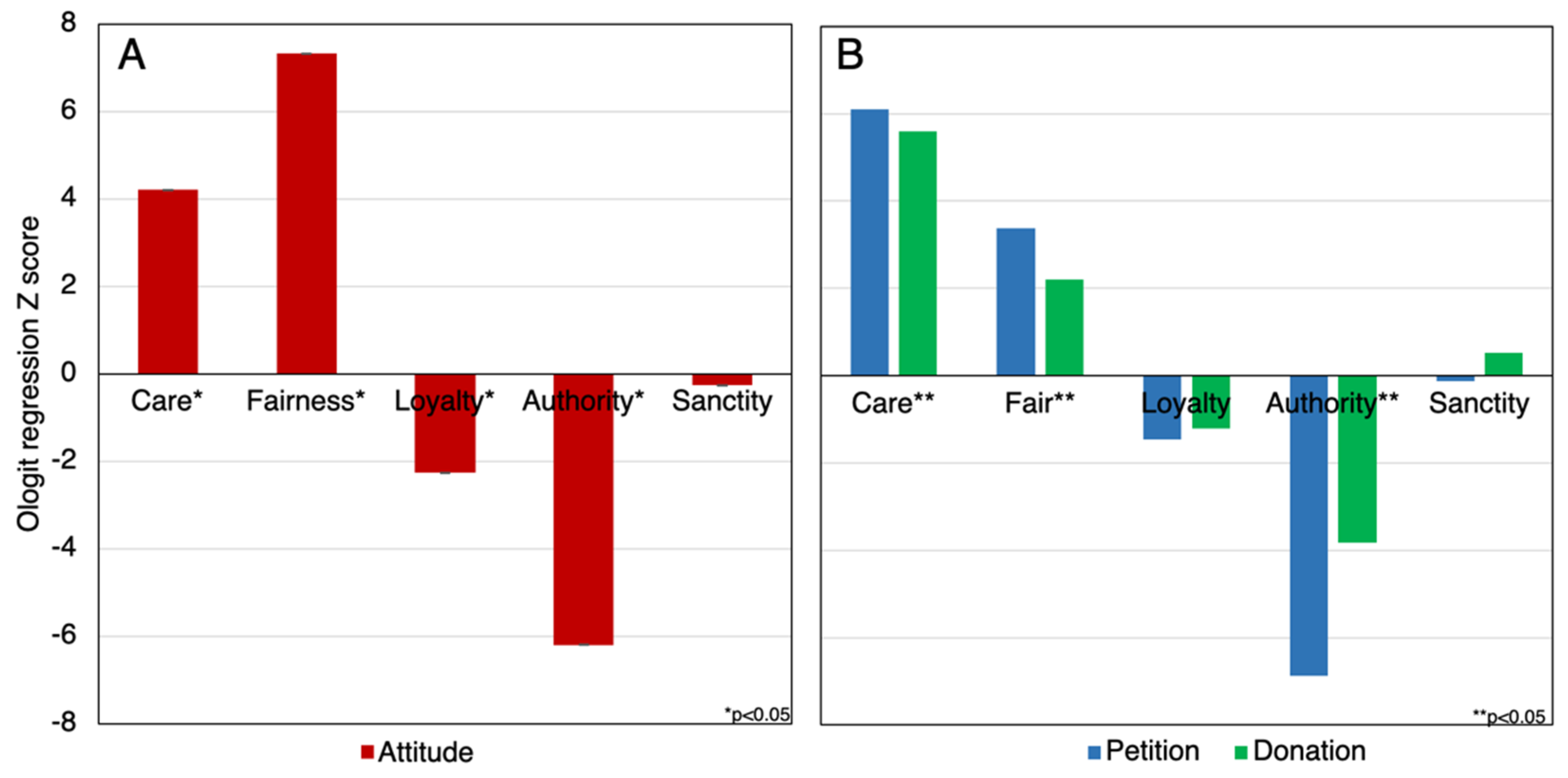

3.1. The Relationship between Moral Foundations and Attitudes towards Refugees

3.2. The Effect of Moral Foundational Framing on Shifting Attitudes

3.3. The Relationship between Moral Foundations on Pro-Refugee Behaviour

3.4. The Effect of Moral Foundational Framing on Pro-Refugee Behaviour

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Framing Words and Terms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Word Count | |||||

| Care | Fairness | Sanctity | Loyalty | Control | |

| Frame 1 | 145 | 142 | 141 | 146 | 181 |

| Frame 2 | 140 | 131 | 130 | 137 | 107 |

| Frame 3 | 20 | 19 | 22 | 19 | 11 |

| Total | 305 | 292 | 293 | 302 | 299 |

| Framing Phrases | |||||

| Frame 1 | welcoming the stranger | justice…for all | rooted in…decency | looking after one another | n/a |

| treating the neglected | equality…for all | rooted in…purity | Loyalty to our nation | n/a | |

| giving shelter | granting equality | (does not) compromisee thnic…integrity | (does not) compromise the loyalty | n/a | |

| compassionate thing to do | just thing to do | (does not) compromise racial…integrity | …for one another | n/a | |

| Phrases | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Total Words | 12 | 10 | 10 | 14 | |

| Moral Words | 7 | 7 | 8 | 10 | |

| Frame 2 | caring for all | fairness for all | promoting purity | loyalty to our great nation | n/a |

| preventing harm | preventing injustice | preventing infringements on sanctity | ensuring we excel at upholding | n/a | |

| letting down a vulnerable group | denying basic principle of justice | sullying the greatness | great name | n/a | |

| putting them in harm’s way | free from injustice | believes in the inviolability | does not compromise this country | n/a | |

| free from danger, | (free from) oppression | ensure the purity of this country | …enhances it | n/a | |

| …violence | (free from) inequality | is upheld | our great people | n/a | |

| not coloured by harm | not coloured by injustice | is uncompromised | leading nations… | n/a | |

| Phrases | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | n/a |

| Total Words | 23 | 23 | 23 | 24 | |

| Moral Words | 12 | 10 | 12 | 12 | |

| Frame 3 | increasing care | increasing fairness | protecting pure values | maintaining country’s greatness | n/a |

| Treatment | Care | Fairness | Sanctity | Loyalty | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

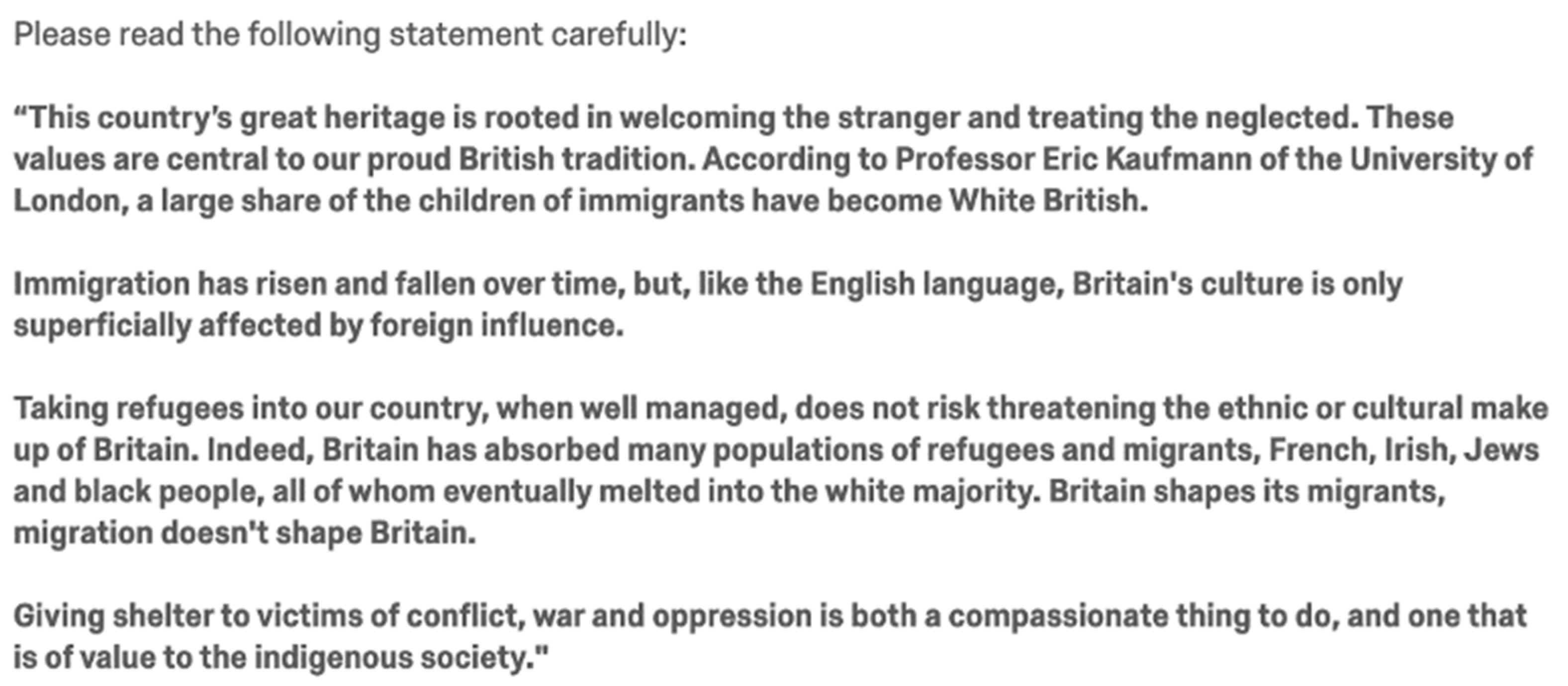

| Vignette | 1. Please read the following statement carefully: | ||||

| “This country’s great heritage is rooted in welcoming the stranger and treating the neglected. These values are central to our proud British tradition. According to Professor Eric Kaufmann of the University of London, a large share of the children of immigrants have become White British. Immigration has risen and fallen over time, but, like the English language, Britain’s culture is only superficially affected by foreign influence. Taking refugees into our country, when well managed, does not risk threatening the ethnic or cultural make up of Britain. Indeed, Britain has absorbed many populations of refugees and migrants, French, Irish, Jews and black people, all of whom eventually melted into the white majority. Britain shapes its migrants, migration doesn’t shape Britain. Giving shelter to victims of conflict, war and oppression is both a compassionate thing to do, and one that is of value to the indigenous society.” | “This country’s great heritage is rooted in justice and equality for all. These values are central to our proud British tradition. According to Professor Eric Kaufmann of the University of London, a large share of the children of immigrants have become White British. Immigration has risen and fallen over time, but, like the English language, Britain’s culture is only superficially affected by foreign influence. Taking refugees into our country, when well managed, does not risk threatening the ethnic or cultural make up of Britain. Indeed, Britain has absorbed many populations of refugees and migrants, French, Irish, Jews and black people, all of whom eventually melted into the white majority. Britain shapes its migrants, migration doesn’t shape Britain. Granting equality to victims of conflict, war and oppression is both a just thing to do, and one is of value to the indigenous society.” | “This country’s great heritage is rooted in decency and purity. These values are central to our proud British tradition. According to Professor Eric Kaufmann of the University of London, a large share of the children of immigrants have become White British. Immigration has risen and fallen over time, but, like the English language, Britain’s culture is only superficially affected by foreign influence. Taking refugees into our country, when well managed, does not risk threatening the ethnic or cultural make up of Britain. Indeed, Britain has absorbed many populations of refugees and migrants, French, Irish, Jews and black people, all of whom eventually melted into the white majority. Britain shapes its migrants, migration doesn’t shape Britain. Taking in victims of conflict, war and oppression is the right thing to do, and does not compromise the ethnic and racial integrity of this country.” | “This country’s great heritage is rooted in looking after one another. Loyalty to our nation is central to our proud British tradition. According to Professor Eric Kaufmann of the University of London, a large share of the children of immigrants have become White British. Immigration has risen and fallen over time, but, like the English language, Britain’s culture is only superficially affected by foreign influence. Taking refugees into our country, when well managed, does not risk threatening the ethnic or cultural make up of Britain. Indeed, Britain has absorbed many populations of refugees and migrants, French, Irish, Jews and black people, all of whom eventually melted into the white majority. Britain shapes its migrants, migration doesn’t shape Britain. Taking in victims of conflict, war and oppression is the right thing to do, and does not compromise the loyalty we have for one another, or our country.” | Policy formation is one of the key aspects to modern government. Policies address key areas of both day-to-day citizen life, as well as the direction of the country as whole. A bad policy can cost a government power, where the electorate respond at the next election. Policies can be both partisan and bipartisan, but typically require a parliamentary majority to be enacted, in countries that utilise a parliamentary democracy. At times, a major policy decision will be decided by way of a referendum. Referenda are an example of direct democracy, wherein the people make a decision directly. Switzerland is often cited as an example of a country that regularly utilises referenda. The role of lobbying groups in influencing government policy is an area of the workings of modern government that is deemed as undermining democracy. Lobbying groups and lobbyists do the work of those who pay them, allowing those with greater access to money, greater ability to hire forces for lobbying. Recent moves have been taken in countries such as the US and the UK to limit the influence of lobbyists. | |

| Speech | 2. Below is an excerpt from the speech of politician, Candidate X, who is running in the upcoming election. This part of the speech relates to his refugee policy. | 2...This part of the speech relates to his views about election reform. | |||

| “My vision for this country is based on the principle of caring for all and preventing harm to those most in need of protection. I think it is regrettable that this great country only accepted 10,000 refugees in 2018—we are letting down a vulnerable group of human beings, and putting them in harm’s way. I believe we are ignoring one of this country’s great values and should strive to rectify this immediately. Every human being is born with the right to live a life that is free from danger and violence Seeing to it that refugees are given this right should be a priority for all of us. Our policies should reflect this goal. Vote for me, and I will fight for the right of every human being to live a life that is not coloured by harm.” | “My vision for this country is based on the principle of fairness for all and preventing injustice to those most in need of protection. I think it is regrettable that this great country only accepted 10,000 refugees in 2018—we are denying the basic principle of justice for all, and ignoring one of this country’s great values and should strive to rectify this immediately. Every human being is born with the right to live a life that is free from injustice, oppression and inequality. Seeing to it that refugees are given this right should be a priority for all of us. Our policies should reflect this goal. Vote for me, and I will fight for the right of every human being to live a life that is not coloured by injustice.” | “My vision for this country is based on the principles of promoting purity and preventing infringements on the sanctity of our society. I think it is regrettable that this great country only accepted 10,000 refugees in 2018—we are sullying this country’s greatness by failing to live up to what we could be and should strive to rectify this immediately. Every human being is born with the right to live a life that allows them to strive towards their potential. Seeing to that that refugees are given their rights should be a priority for anyone who believes in the inviolability of this country. Our policies should reflect this goal. Vote for me, and I will fight to ensure the purity of this country and its vision is upheld and uncompromised.” | “My vision for this country is based on the principle of loyalty to our great nation and ensuring we excel at upholding its great name. I think it is regrettable that this great country only accepted 10,000 refugees in 2018—we are letting down a vulnerable group of human beings, and putting them in harm’s way. I believe we are ignoring one of this country’s great values and should strive to rectify this immediately. Protecting fellow humans from danger, violence and threat, does not compromise this country, in fact, it enhances it. Seeing to it that refugees are given this right should be a priority for all of us. Our policies should reflect this goal. Vote for me, and I will fight to ensure this our great people continue to be among the leading nations on earth.” | “There is a need for a rethinking of the way in which elections in this country are judged. For too long, the First-Past-the-Post system has disadvantaged certain voices while granting too much weight to other voices. While the thinking of using this system might have made sense in the past, the UK is in need of modernising. By switching to a Proportional Representation (PR) system, this country will take a step in the right direction. The PR system is already being used by many other countries around the world, the system allows for a much realer realisation of the fundamental principle underlying democracy, “one person, one vote”. | |

| Policy | In the interest of increasing the care of refugees, Candidate X will increase refugee settlements in this country by 5%. | In the interest of increasing fairness towards refugees, Candidate X will increase refugee settlements in this country by 5%. | In the interest of protecting the pure values of this country, Candidate X will increase refugee settlements in this country by 5%. | In the interest of maintaining our country’s greatness Candidate X will increase refugee settlements in this country by 5%. | Candidate X will increase refugee settlements in this country by 5%. |

References

- UNHCR. Asylum in the UK. 2019. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/asylum-in-the-uk.html (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Podesta, J. The Climate Crisis, Migration, and Refugees. The Brookings Institute. 2019. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Brookings_Blum_2019_climate.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Blinder, S. Imagined Immigration: The Impact of Different Meanings of ‘Immigrants’ in Public Opinion and Policy Debates in Britain. Political Stud. 2013, 63, 80–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getmansky, A.; Sınmazdemir, T.; Zeitzoff, T. Refugees, xenophobia, and domestic conflict. J. Peace Res. 2018, 55, 491–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Facchini, G.; Margalit, Y.; Nakata, H. Countering public opposition to immigration: The impact of information campaigns. Eur. Econ. Rev. 2021, 141, 103959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, L.G.; Abdelaaty, L. Ethnic diversity and attitudes towards refugees. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2018, 45, 1833–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Miano, A.; Stantcheva, S. Immigration and Redistribution; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnert, L.V. Refugee resettlement, redistribution and growth. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2018, 54, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grigorieff, A.; ROTH, C.; Ubfal, D. Does Information Change Attitudes Towards Immigrants? Representative Evidence from Survey Experiments. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangor, C.; Sechrist, G.B.; Jost, J.T. Changing Racial Beliefs by Providing Consensus Information. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbs, M.; Crano, W.D. Outgroup Accountability in the Minimal Group Paradigm: Implications for Aversive Discrimination and Social Identity Theory. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanchard, F.A.; Lilly, T.; Vaughn, L.A. Reducing the Expression of Racial Prejudice. Psychol. Sci. 1991, 2, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluck, E.L. Peer Pressure Against Prejudice: A Field Experimental Test of a National High School Prejudice Reduction Program; Working Paper; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, E. Assimilation and the Immigration Debate: Shifting People’s Attitudes. The London School of Economics and Political Science. 2016. Available online: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/assimilation-and-the-immigration-debate-shifting-peoples-attitudes/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Galinsky, A.D.; Moskowitz, G.B. Perspective-taking: Decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000, 78, 708–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecheler, S.; De Vreese, C.H. How Long Do News Framing Effects Last? A Systematic review of Longitudinal Studies. Ann. Int. Commun. Assoc. 2016, 40, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J.N.; McDermott, R. Emotion and the Framing of Risky Choice. Politics Behav. 2008, 30, 297–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J.N.; Nelson, K.R. Framing and Deliberation: How Citizens’ Conversations Limit Elite Influence. Am. J. Politics Sci. 2003, 47, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, J.G.; Willer, R. Resolving the Progressive Paradox: Conservative Value Framing of Progressive Economic Policies Increases Candidate Support. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3385818 (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Feygina, I.; Jost, J.T.; Goldsmith, R.E. System Justification, the Denial of Global Warming, and the Possibility of “System-Sanctioned Change”. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2009, 36, 326–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Graham, J.; Haidt, J.; Koleva, S.; Motyl, M.; Iyer, R.; Wojcik, S.; Ditto, P. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2013, 47, 55–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, R.; Koleva, S.; Graham, J.; Ditto, P.; Haidt, J. Understanding Libertarian Morality: The Psychological Dispositions of Self-Identified Libertarians. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e42366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fisk, K. Refugee Geography and the Diffusion of Armed Conflict in Africa. Civ. Wars 2014, 16, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherif, M. Experimental Study of Positive and Negative Intergroup Attitudes between Experimentally Produced Groups: Robbers Cave Study; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Yitmen, Ş.; Verkuyten, M. Feelings toward refugees and non-Muslims in Turkey: The roles of national and religious identifications, and multiculturalism. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2017, 48, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haidt, J.; Graham, J.; Joseph, C. Above and Below Left–Right: Ideological Narratives and Moral Foundations. Psychol. Inq. 2009, 20, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornhill, R.; Fincher, C.L. The Parasite-Stress Theory of Values and Sociality: Infectious Disease, History and Human Values Worldwide; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, L.; Pedriana, N.; Gifford, C.; Mcauley, J.W.; Fülöp, M. Examining Moral Foundations Theory through Immigration Attitudes. Athens J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 9, 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Captari, L.E.; Shannonhouse, L.; Hook, J.N.; Aten, J.D.; Davis, E.B.; Davis, D.E.; Van Tongeren, D.; Hook, J.R. Prejudicial and Welcoming Attitudes toward Syrian Refugees: The Roles of Cultural Humility and Moral Foundations. J. Psychol. Theol. 2019, 47, 123–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, C.J.; Tipton, E.; Yeager, D.S. Behavioural science is unlikely to change the world without a heterogeneity revolution. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021, 5, 980–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palan, S.; Schitter, C. Prolific.ac—A subject pool for online experiments. J. Behav. Exp. Finance 2018, 17, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (Version 1.2) [Computer Software]. 2020. Available online: https://www.jamovi.org (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (Version 3.6). 2019. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/ (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ripley, B.; Venables, W.; Bates, D.M.; Hornik, K.; Gebhardt, A.; Firth, D. MASS: Support Functions and Datasets for Venables and Ripley’s MASS. [R package]. 2018. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=MASS (accessed on 10 June 2020).

| Demographic Information | Care (n = 210) | Fair (n = 215) | Loyalty (n = 217) | Sanctity (n = 216) | Control (n = 218) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 83 | 85 | 89 | 82 | 84 |

| Female | 126 | 128 | 125 | 132 | 130 |

| White | 178 | 184 | 189 | 176 | 189 |

| Ethnic Minority | 32 | 31 | 28 | 40 | 29 |

| Bachelor’s Degree and Higher | 105 | 102 | 104 | 109 | 112 |

| Less Than Bachelor’s | 105 | 113 | 113 | 107 | 106 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mobayed, T.; Sanders, J.G. Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050118

Mobayed T, Sanders JG. Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(5):118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050118

Chicago/Turabian StyleMobayed, Tamim, and Jet G. Sanders. 2022. "Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 5: 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050118

APA StyleMobayed, T., & Sanders, J. G. (2022). Moral Foundational Framing and Its Impact on Attitudes and Behaviours. Behavioral Sciences, 12(5), 118. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12050118