Examining the Mediating Effect of Customer Experience on the Emotions–Behavioral Intentions Relationship: Evidence from the Passenger Transport Sector

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Formation

2.1. Customer Experience

2.1.1. Definitions

2.1.2. Historical Evolution

2.1.3. Measurement Instruments

2.2. Emotions

2.3. Behavioral Intentions

2.4. The Role of Customer Experience in the Emotions and Behavioral Intentions Relationship

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurement Instruments

3.3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Testing the Examined Scales (Research Hypotheses 1, 2 and 3)

- Research Hypothesis 1 has been supported, with the onboard customer experience scale composed of four distinct dimensions: entertainment (three items), escapism (three items), education (three items) and aesthetic (three items).

- Research Hypothesis 2 has been supported, and the emotion construct in passenger transportation services is composed of two distinct dimensions. The first one (positive emotions) expresses the positive emotions of the customers (whether they feel contentment, happiness or love), and the second one (negative emotions) expresses the negative emotions of the customers (whether they feel angry, sad, fearful or ashamed).

- Research Hypothesis 3 has been supported, and the customers’ behavioral intentions can be measured through one distinct dimension composed of seven items that reflect their word of mouth, repurchase and revisiting intentions.

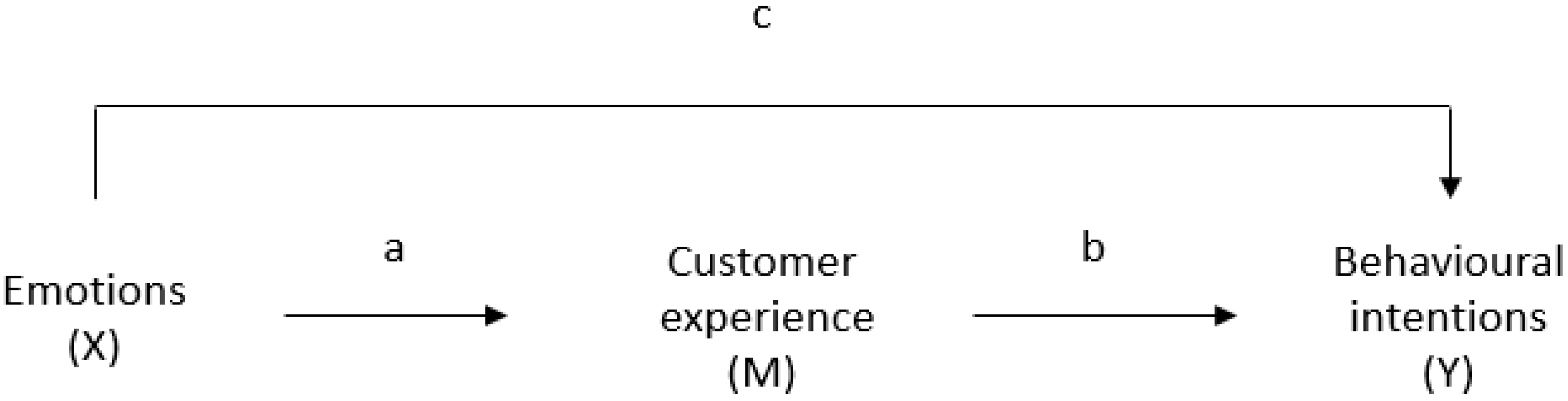

4.2. Testing the Mediating Effect (Research Hypothesis 4)

- Step 1. A simple regression analysis with X (emotions) predicting Y (behavioral intentions) to test for path c [Behavioral Intentions = bo + b1 × Emotions + e].

- Step 2. A simple regression analysis with X (emotions) predicting M (customer experience) to test for path a [Customer Experience = bo + b1 × Emotions + e].

- Step 3. A simple regression analysis with M (customer experience) predicting Y (behavioral intentions) to test the significance of path b [Behavioral Intentions = bo + b1 × Customer Experience + e].

- Step 4. A multiple regression analysis with X and M predicting Y [Behavioral Intentions = bo + b1 × Emotions + b2 × Customer Experience + e].

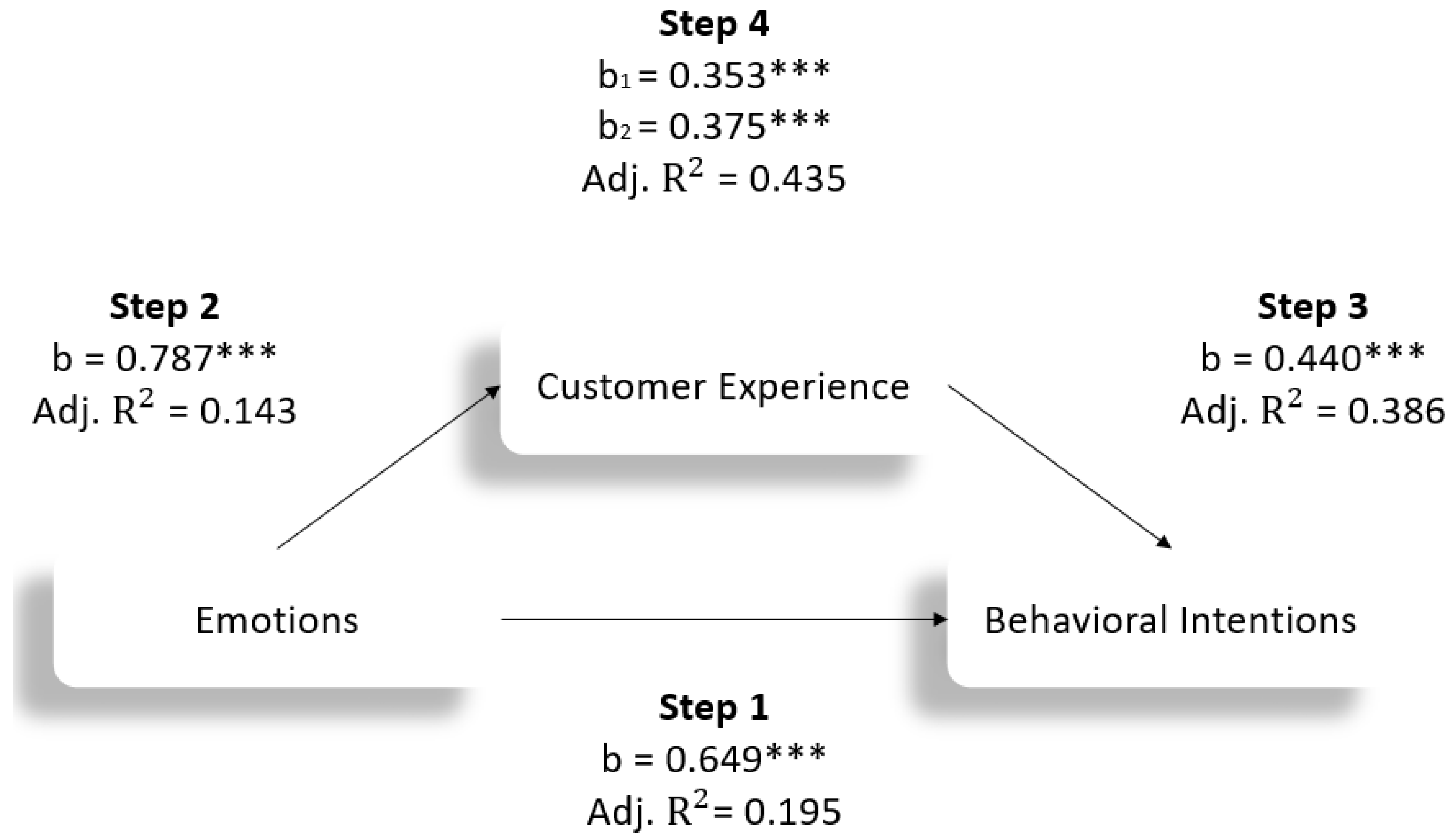

- In the first regression equation (Table 5), the customers’ behavioral intentions were affected by their emotions (Adj. R2 = 0.195) [Behavioral Intentions = 5.516 + 0.649 × Emotions + e].

- In the second regression equation (Table 6), the customers’ emotions had an impact on their customer experience (Adj. R2 = 0.143) [Customer Experience = 13.790 + 0.787 × Emotions + e].

- In the third regression equation (Table 7), the customers’ experience had an impact on their behavioral intentions (Adj. R2 = 0.386) [Behavioral Intentions = 10.706 + 0.440 × Customer Experience + e].

- In the multiple regression equation (Table 8), the customers’ behavioral intentions were affected by the customers’ emotions and customer experience (Adj. R2 = 0.435) [Behavioral Intentions = 0.340 + 0.353 × Emotions + 0.375 × Customer Experience + e].

5. Conclusions and Suggestions for Future Research

5.1. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

5.2. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| CFA | Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

Appendix A. Measurement Instruments

| Customer Experience |

| Entertainment |

| This journey experience was fun |

| This journey was entertaining |

| I really enjoyed this travel experience |

| Education |

| I learned a lot through my travel experience |

| This travel experience stimulated my curiosity to learn new things |

| I completely escaped from reality during this travel experience |

| Escapism |

| This travel experience stimulated my curiosity to learn new things |

| This journey made me feel I was living in a different time or place |

| I completely escaped from reality during this travel experience |

| Aesthetic |

| It was pleasant just being in this ship |

| The setting of the ship provided pleasure to my senses |

| The setting of the ship really showed attention to detail in terms of design |

| Emotions |

| Positive emotions |

| I feel Contentment (Contended, Peaceful, Fulfilled) |

| I feel Happy (Optimistic, Pleased, Thrilled, Enthusiastic) |

| I feel Love (Romantic, Sentimental, Warm-hearted) |

| Negative emotions |

| I feel Angry (Frustrated, Irritated, Unfulfilled) |

| I feel Sad (Depressed, Miserable, Helpless) |

| I feel Fear (Scared, Afraid, Worried, Nervous) |

| I feel Ashamed (Embarrassed, Ashamed, Humiliated) |

| Behavioral intentions |

| I would speak positively about the employees of this shipping company to others |

| I would recommend traveling with this shipping company to friends |

| I would recommend traveling with this shipping company to family members |

| I would mention to others that I traveled with this shipping company |

| I would make sure that others knew that I traveled with this shipping company |

| I intend to continue traveling with this shipping company |

| I plan to travel again with this shipping company in the near future |

References

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witell, L.; Kowalkowski, C.; Perks, H.; Raddats, C.; Schwabe, M.; Benedettini, O.; Burton, J. Characterizing customer experience management in business markets. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 24, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Reinartz, W. Creating enduring customer value. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 36–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rapp, A.; Baker, T.L.; Bachrach, D.G.; Ogilvie, J.; Beitelspacher, L.S. Perceived Customer Showrooming Behavior and the Effect on Retail Salesperson Self-Efficacy and Performance. J. Retail. 2015, 91, 358–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthiou, A.; Hickman, E.; Klaus, P. Beyond good and bad: Challenging the suggested role of emotions in customer experience (CX) research. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durna, U.; Dedeoglu, B.B.; Balikcioglu, S. The role of servicescape and image perceptions of customers on behavioural intentions in the hotel industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 27, 1728–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.; Buoye, A.; Keiningham, T.L.; Aksoy, L. The practitioners’ path to customer loyalty: Memorable experiences or frictionless experiences? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaji, M.S.; Khong, K.W.; Chong, A.Y.L. Determinants of negative word-of-mouth communication using social networking sites. Inf. Manag. 2016, 53, 528–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyrväinen, O.; Karjaluoto, H.; Saarijärvi, H. Personalization and hedonic motivation in creating customer experiences and loyalty in omnichannel retail. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, N.; Vermeir, I.; Slabbinck, H.; Lariviere, B.; Mauri, M.; Russo, V. A neurophysiological exploration of the dynamic nature of emotions during the customer experience. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedenthal, P.; Ric, F. Psychology of Emotion, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9781848725126. [Google Scholar]

- Frijda, N.H. The Emotions; Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme; Cambridge University Press: Paris, France, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleef, G.A. The Interpersonal Dynamics of Emotion: Toward an Integrative Theory of Emotions as Social Information; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Van Kleef, G.A.; Lange, J. How hierarchy shapes our emotional lives: Effects of power and status on emotional experience, expression, and responsiveness. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020, 33, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pantouvakis, A.; Gerou, A. The Theoretical and Practical Evolution of Customer Journey and Its Significance in Services Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P. Marketing Management: Analysis, Planning and Control; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, N.; Yang, Y. The impact of customer experience on consumer purchase intention in cross-border E-commerce—Taking network structural embeddedness as mediator variable. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, R.; Aagja, J.; Bagdare, S. Customer experience—A review and research agenda. J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2017, 27, 642–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, G.; Osei-Frimpong, K. Examining satisfaction with the experience during a live chat service encounter-implications for website providers. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 76, 494–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; So, K.K.F. Two decades of customer experience research in Hospitality and Tourism: A bibliometric analysis and thematic content analysis. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 100, 103082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, M.; Hamzah, Z.L.B.; Salleh, N.A.M. Customer experience: A systematic literature review and consumer culture theory-based conceptualization. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 135–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A.; Valarie, A.Z.; Berry, L. SERVQUAL: A Multiple-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality. J. Retail. 1988, 64, 12–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer Perceptions of Price, Quality, and Value: A Means–End Model and Synthesis of Evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mithas, S.; Krishnan, M.S.; Fornell, C. Why do customer relationship management applications affect customer satisfaction? J. Mark. 2005, 69, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Reinartz, W.J.; Krafft, M. Customer engagement as a new perspective in customer management. J. Serv. Res. 2010, 13, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, E.V.; Weber, T.B.B.; Bomfim, E.L.; Kato, H.T. Measuring customer experience in service: A systematic review. Serv. Ind. J. 2019, 39, 779–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.A.; Jagdish, S. The Theory of Buyer Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Gary, A.S. A Model for Predictive Measurements of Advertising Effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Lehmann, D.R.; Stuart, J.A. Valuing Customers. J. Mark. Res. 2004, 41, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitner, M.J.; Ostrom, A.L.; Morgan, F.N. Service blueprinting: A practical technique for service innovation. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2008, 50, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, F.R.; Schurr, P.H.; Oh, S. Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships. J. Mark. 1987, 51, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Levy, M.; Kumar, V. Customer Experience Management in Retailing: An Organizing Frame-work. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V. Profitable Customer Engagement: Concept, Metrics and Strategies; SAGE Publications: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hollebeek, L.D.; Glynn, M.S.; Brodie, R.J. Consumer Brand Engagement in Social Media: Conceptualization, Scale Development, and Validation. J. Interact. Mark. 2014, 28, 149–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pine, B.J.; Gilmore, J.H. The Experience Economy: Work is Theatre & Every Business a Stage; Harvard Business Press: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. Experiential marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 1999, 15, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plutchik, R. A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In Theories of Emotion; Academic Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 1980; pp. 3–31. ISBN 978-0-12-558701-3. [Google Scholar]

- Clore, G.L.; Ortony, A.; Foss, M.A. The Psychological Foundations of the Affective Lexicon. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 53, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J.B.; Areni, C.S. Affect and Consumer Behavior; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelkader, S.; Bouslama, N. The role of sense of Community in Mediation between positive emotions and attitudes toward brand and message. J. Mark. Res. Case Stud. 2014, 2014, 349677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujur, F.; Singh, S. Emotions as predictor for consumer engagement in YouTube advertisement. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2018, 15, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quelette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Warshaw, P.R.; Davis, F.D. Disentangling behavioral intention and behavioral expectation. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 21, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A.; Berry, L.L.; Parasuraman, A. The behavioral consequences of service quality. J. Mark. 1996, 60, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Barry, T.E.; Dacin, P.A.; Gunst, R.F. Spreading the word: Investigating antecedents of consumers’ positive word-of-mouth intentions and behaviors in a retailing context. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2005, 33, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Petrick, J.F. Examining the antecedents of brand loyalty from an investment model perspective. J. Travel Res. 2008, 47, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D.; Rasoolimanesh, S.M. First-time versus repeat tourism customer engagement, experience, and value co-creation: An empirical investigation. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A.; Russell, J.A. An Approach to Environmental Psychology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Holbrook, M.B.; Batra, R. Assessing the role of emotions as mediators of consumer responses to advertising. J. Consum. Res. 1987, 14, 404–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liljander, V.; Strandvik, T. Emotions in service satisfaction. Int. J. Serv. Ind. Manag. 1997, 8, 148–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnoth, J. Tourism motivation and expectation formation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1997, 24, 283–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeelenberg, M.; Pieters, R. Beyond valence in customer dissatisfaction: A review and new findings on behavioral responses to regret and disappointment in failed services. J. Bus.Res. 2004, 57, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigné, J.E.; Andreu, L.; Gnoth, J. The theme park experience: An analysis of pleasure, arousal and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2005, 26, 833–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faullant, R.; Matzler, K.; Mooradian, T.A. Personality, basic emotions, and satisfaction: Primary emotions in the mountaineering experience. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 1423–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F. Shopping risk perceptions: Effects on tourists’ emotions, satisfaction and expressed loyalty intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.C. Sadder but wiser or happier and smarter? A demonstration of judgment and decision making. J. Psychol. 2007, 141, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Jeong, C. Multi-dimensions of patrons’ emotional experiences in upscale restaurants and their role in loyalty formation: Emotion scale improvement. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2013, 32, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. The effect of consumption emotions on satisfaction and word-of-mouth communications. Psychol. Mark. 2007, 24, 1085–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladhari, R. Service quality, emotional satisfaction, and behavioural intentions: A study in the hotel industry. Manag. Serv. Qual. 2009, 19, 308–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rojas, C.; Camarero, C. Visitors’ experience, mood and satisfaction in a heritage context: Evidence from an interpretation center. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 525–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.R.; San Martin, H. Tourist satisfaction: A cognitive–affective model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosany, S.; Prayag, G. Patterns of tourists’ emotional responses, satisfaction, and intention to recommend. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.S.; Namkung, Y. Perceived quality, emotions, and behavioral intentions: Application of an extended Mehrabian–Russell model to restaurants. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 451–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fast, N.J.; Sivanathan, N.; Mayer, N.D.; Galinsky, A.D. Power and overconfident decision-making. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2012, 117, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppelwieser, V.G.; Klaus, P.; Manthiou, A.; Boujena, O. Consumer responses to planned obsolescence. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Zaki, M.; Lemon, K.N.; Urmetzer, F.; Neely, A. Gaining customer experience insights that matter. J. Serv. Res. 2019, 22, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Keyser, A.; Verleye, K.; Lemon, K.N.; Keiningham, T.L.; Klaus, P. Moving the customer experience field forward: Introducing the touchpoints, context, qualities (TCQ) nomenclature. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakeye, P.C.; Crompton, J.L. Image differences between prospective, first-time, and repeat visitors to the Lower Rio Grande Valley. J. Trav. Res. 1991, 30, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sönmez, S.F.; Graefe, A.R. Determining future travel behavior from past travel experience and perceptions of risk and safety. J. Trav. Res. 1998, 37, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, P.P.; Maklan, S. Towards a better measure of customer experience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Kim, H.S. The impact of servicescape on customer experience quality through employee-to-customer interaction quality and peer-to-peer interaction quality in hedonic service settings. Asian J. Mark. 2015, 17, 73–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.; Fatma, M.; Islam, J.; Rahman, Z. Brand engagement and experience in online services. J. Serv. Mark. 2019, 34, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D. Customers’ service-related engagement, experience, and behavioral intent: Moderating role of age. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Schmitt, B.H.; Zarantonello, L. Brand Experience: What Is It? How Is It Measured? Does It Affect Loyalty? J. Mark. 2009, 73, 52–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgihan, A. Gen Y customer loyalty in online shopping: An integrated model of trust, user experience and branding. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016, 61, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.C.; Verhoef, P.C. The impact of positive and negative emotions on loyalty intentions and their interactions with customer equity drivers. J. Bus. Res. 2017, 80, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed.; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, H.F.; Rice, J. Little Jiffy, Mark IV. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 1974, 34, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Tatoglu, E.; Glaister, A.J.; Demirbag, M. Talent management motives and practices in an emerging market: A comparison between MNEs and local firms. J. World Bus. 2016, 51, 278–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J.H. Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2007, 42, 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D.; Coughlan, J.; Mullen, M.R. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Bus. Res. Methods 2008, 6, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McColl-Kennedy, J.R.; Gustafsson, A.; Jaakkola, E.; Klaus, P.; Radnor, Z.J.; Perks, H.; Friman, M. Fresh perspectives on customer experience. J. Serv. Mark. 2015, 29, 430–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosavi, S.M.; Sangari, M.S.; Keramati, A. An integrative framework for customer switching behavior. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 1067–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 2009, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, L.; Jaakkola, E. Customer experience: Fundamental premises and implications for research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2020, 48, 630–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahrous, A.A.; Hassan, S.S. Achieving superior customer experience: An investigation of multichannel choices in the travel and tourism industry of an emerging market. J. Trav. Res. 2017, 56, 1049–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreini, D.; Pedeliento, G.; Zarantonello, L.; Solerio, C. A renaissance of brand experience: Advancing the concept through a multi-perspective analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 91, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, J.; Jang, S. Perceived values, satisfaction, and behavioral intentions: The role of familiarity in Korean restaurants. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Luo, P.; Wang, H. An influence framework on product word-of-mouth (WoM) measurement. Inf. Manag. 2017, 54, 228–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy | 0.832 | |

| Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity | Approx. Chi-Square | 5926.251 |

| Df | 21 | |

| Sig. | 0.000 | |

| Factor | Initial Eigenvalues | Extraction Sums of Squared Loadings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | Total | % of Variance | Cumulative % | |

| 1 | 4.551 | 65.008 | 65.008 | 4.234 | 60.487 | 60.487 |

| 2 | 0.932 | 13.309 | 78.371 | |||

| 3 | 0.616 | 8.795 | 87.113 | |||

| 4 | 0.394 | 5.631 | 92.744 | |||

| 5 | 0.371 | 5.300 | 98.044 | |||

| 6 | 0.118 | 1.693 | 99.737 | |||

| 7 | 0.018 | 0.263 | 100.000 | |||

| Extraction Method: Principal Axis Factoring | ||||||

| Fit Index | Customer Experience | Emotions | Behavioral Intentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| GFI | 0.972 | 0.982 | 1.000 |

| AGFI | 0.931 | 0.955 | 0.998 |

| NFI | 0.981 | 0.976 | 1.000 |

| NNFI/TLI | 0.969 | 0.963 | 1.003 |

| CFI | 0.985 | 0.981 | 1.000 |

| RMSEA | 0.067 | 0.068 | 0.000 |

| RMR | 0.074 | 0.046 | 0.002 |

| Model Correlations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions | Customer Experience | Behavioral Intentions | |

| Emotions | 1 | 0.380 | 0.442 |

| Customer experience | 0.380 | 1 | 0.622 |

| Behavioral intentions | 0.442 | 0.622 | 1 |

| All correlations are significant at the 0.01 level. | |||

| Dependent Variable: Behavioral Intentions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. R2 = 0.195, F-value = 203.882 p-value < 0.001 | B | t | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 5.516 | 3.213 | 0.001 |

| Emotions | 0.649 | 14.279 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable: Customer Experience | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. R2 = 0.143, F-value = 141.378 p-value < 0.001 | B | t | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 13.790 | 5.514 | 0.000 |

| Emotions | 0.787 | 11.890 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable: Behavioral Intentions | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. R2 = 0.386, F-value = 527.926 p-value < 0.001 | B | t | Sig. |

| (Constant) | 10.706 | 12.392 | 0.000 |

| Customer Experience | 0.440 | 22.977 | 0.000 |

| Dependent Variable: Behavioral Intentions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adj. R2 = 0.435, F-value = 323.744 p-value < 0.001 Durbin–Watson = 1.991 | B | Sig. | Tolerance | VIF |

| (Constant) | 0.340 | - | - | - |

| Emotions | 0.353 (b1) | 0.000 | 0.856 | 1.169 |

| Customer experience | 0.375 (b2) | 0.000 | 0.856 | 1.169 |

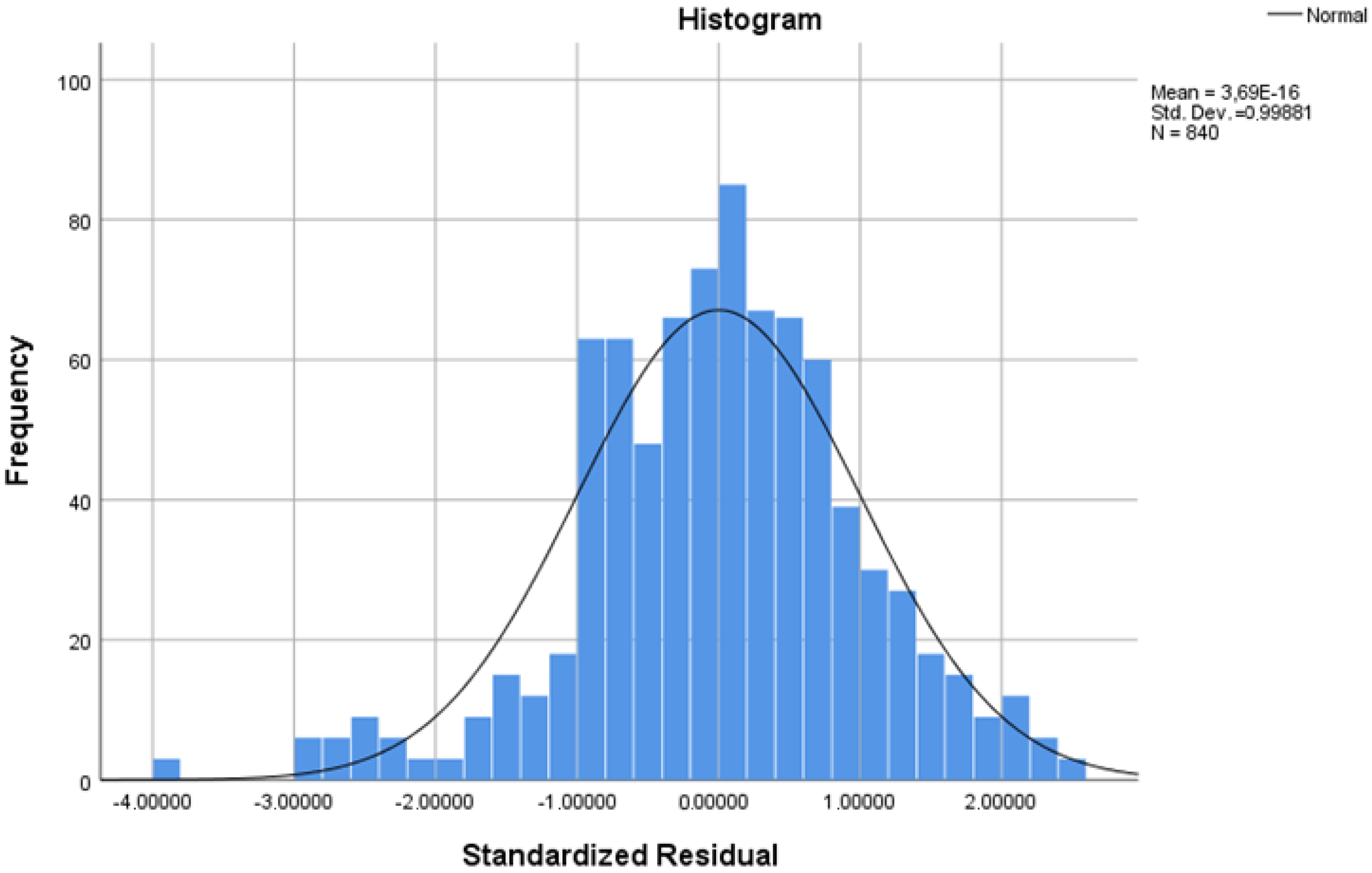

| Test of Normality | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kolmogorov–Smirnov | Shapiro–Wilk | |||||

| Statistic | Df | Sig. | Statistic | Df | Sig. | |

| Unstandardized Residual | 0.052 | 840 | 0.000 | 0.995 | 840 | 0.005 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gerou, A. Examining the Mediating Effect of Customer Experience on the Emotions–Behavioral Intentions Relationship: Evidence from the Passenger Transport Sector. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110419

Gerou A. Examining the Mediating Effect of Customer Experience on the Emotions–Behavioral Intentions Relationship: Evidence from the Passenger Transport Sector. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(11):419. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110419

Chicago/Turabian StyleGerou, Anastasia. 2022. "Examining the Mediating Effect of Customer Experience on the Emotions–Behavioral Intentions Relationship: Evidence from the Passenger Transport Sector" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 11: 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110419

APA StyleGerou, A. (2022). Examining the Mediating Effect of Customer Experience on the Emotions–Behavioral Intentions Relationship: Evidence from the Passenger Transport Sector. Behavioral Sciences, 12(11), 419. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12110419