Motivational Orientation in University Athletes: Predictions Based on Emotional Intelligence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

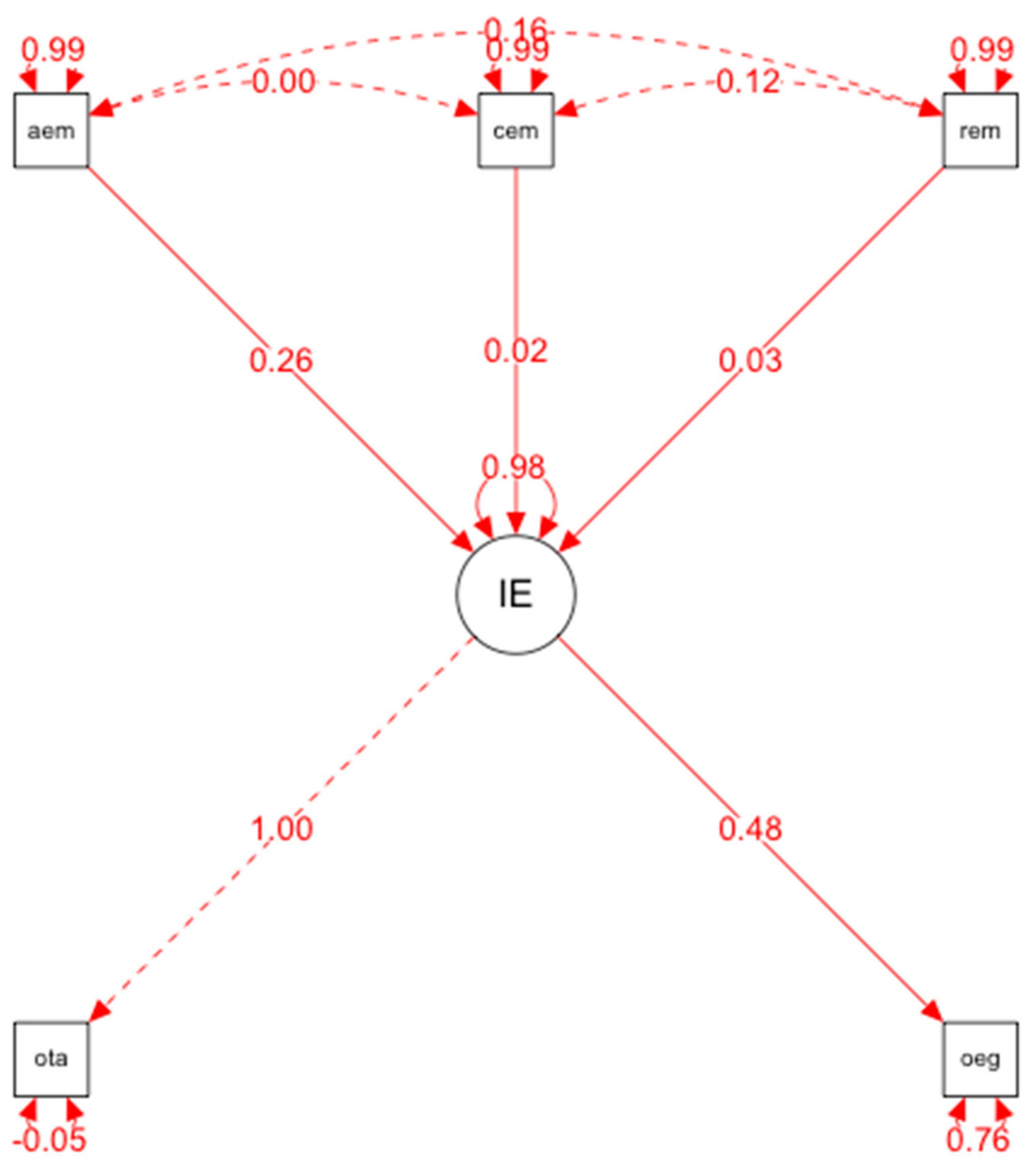

Structural Equation Model

- -

- Overall fit indices (evaluate the model overall) and are adequate: p < 0.001, RMSEA = 0.00, GFI = 0.99.

- -

- Incremental or comparative fit indices (compare the proposed model with the model of independence or absence of relationship between the variables): NNFI= 1.095; TLI = 0.963; CFI = 1; IFI = 1.02.

- -

- Parsimony indices (assessing the quality of the model fit in terms of the number of coefficients estimated to achieve that level of fit): AGFI = 0.97.

- -

- There is a positive and direct relationship between emotional intelligence and ego orientation (= 0.048, p < 0.001). This allows us to affirm that emotional intelligence is a variable that predicts ego motivation.

- -

- There is a relationship that is neither direct nor positive between emotional intelligence and task orientation.

- -

- Therefore, based on these results, we can affirm that emotional intelligence is a predictor of ego-motivation.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- -

- There is a direct and positive relationship between emotional intelligence and motivation towards the ego.

- -

- Such a direct and positive relationship does not occur in the case of the relationship established between emotional intelligence and task orientation

- -

- It is valuable to continue research in this field of study, as well as to determine the possible contextual variables that may be influencing such results.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nicholls, G. The Competitive and Democratic Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E.L.; Ryan, R.M. The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. J. Res. Personal. 1985, 19, 109–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M.; Deci, E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braithwaite, R.; Spray, C.M.; Warburton, V.E. Motivational climate interventions in physical education: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 628–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, T.; Standage, M. Psychological Needs and the Quality of Student Engagement in Physical Education: Teachers as Key Facilitators. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 262–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, W.; Shen, B. Learning in Physical Education: A Self-Determination Theory Perspective. J. Teach. Phys. Educ. 2017, 36, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Berghe, L.; Vansteenkiste, M.; Cardon, G.; Kirk, D.; Haerens, L. Research on self-determination in physical education: Key findings and proposals for future research. Phys. Educ. Sport Pedagog. 2014, 19, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, S.M.; López-Walle, J.M. Climas motivacionales, necesidades psicológicas básicas y motivación en deportistas de una institución privada. Sinéctica 2022, 59, e1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galeano-Terán, A. Estudio documental de la motivación en Educación Física: Análisis de su evolución. Rev. Cognosis 2021, 6, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, D.M. Differences between psychological aspects in Primary Education and Secondary Education. Motivation, Basic Psychological Needs, Responsibility, Classroom Climate, Prosocial and Antisocial behaviors and Violence. Espiral. Cuad. Del Profr. 2021, 14, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda, J.L.; Nicholls, J.G. Dimensions of achievement motivation in schoolwork and sport. J. Educ. Psychol. 1992, 84, 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Mas, A.; Gimeno, F. La Teoría de Orientación de Metas y la enseñanza de la Educación Física: Consideraciones prácticas. Rev. Latinoam. De Psicol. 2008, 40, 511–522. [Google Scholar]

- Datu, J.A.D.; Valdez, J.P.M.; Yang, W. La vida comprometida académicamente de los estudiantes orientados al dominio: Orden causal entre emociones positivas, metas de dominio y compromiso académico. Rev. De Psicodidáctica 2022, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, S.A.; Duda, J.L.; Barrett, T. Optimización de la participación en la actividad física durante el deporte juvenil: Un enfoque de la teoría de la autodeterminación. Rev. De Cienc. Del Deporte 2016, 34, 1874–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massar, K.; Malmberg, R. Una exploración de la transferencia de la autoeficacia: La autoeficacia académica predice la autoeficacia nutritiva y del ejercicio físico. Rev. De Psicol. Soc. 2017, 32, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, K.B.; Smith, J.; Lubans, D.R.; Ng, J.; Lonsdale, C. Self-determined motivation and physical activity in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Prev. Med. 2014, 67, 270–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. Achievement goals, motivational climate, and motivational processes. In Motivation in Sport and Exercise; Roberts, G.C., Ed.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 1992; pp. 161–176. [Google Scholar]

- Cervelló, E.M.; Santos-Rosa, F.J. Motivation in Sport and achievement goal perspective in young spanish recreational athletes. Percept. Mot. Ski. 2001, 92, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.L.; Sandoval, J.C.A.; Medina, O.E.M.; Ceballos, J.J.M. Motivación en la práctica de Educación Física, en adolescentes que cursan el nivel Medio Superior. Rev. Metrop. De Cienc. Apl. 2021, 4, 260–267. [Google Scholar]

- García-Pascual, F.; González-García, R.; Pérez-Campos, C. Análisis sobre la inteligencia emocional en el alumnado de Educación Física en la etapa secundaria. Rev. De Investig. En Psicol. Social 2022, 9, 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P. What is emotional intelligence. In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Implications for Educators; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, J.D.; Salovey, P.; Caruso, D.R. Models of emotional intelligence. In Handbook of Intelligence; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 396–420. [Google Scholar]

- Peña, M.; Rey, L.; Extremera, N. Satisfacción vital y compromiso en educadores de primaria y primaria: Diferencias en inteligencia emocional y género. Rev. De Psicodidáctica 2012, 17, 341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Goleman, D. Inteligencia Emocional; Kairós: Barcelona, Spain, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, C.B.; Buñuel, P.S.L. Emociones en Educación Física: Una revisión bibliográfica (2015–2017). Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2019, 36, 597–603. [Google Scholar]

- Bruña, I.M.; Almagro, B.J.; Paramio-Pérez, G. El desarrollo de la educación emocional a través de la Educación Física escolar. E-Motion Rev. De Educ. Mot. E Investig. 2015, 5, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Madrona, P.; Martínez López, M. Emociones percibidas, por alumnos y maestros, en Educación Física en 6.°curso de primaria. Educ. XX1 Rev. De La Fac. De Educ. 2016, 19, 179–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solé, J.N.; Lavega-Burgués, P.; Buñuel, P.S.L. La educación de las emociones a través de la educación física. EmásF Rev. Digit. De Educ. Física 2021, 12, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Suero, S.F.; Almagro, B.J.; Buñuel, P.S.L. Necesidades psicológicas, motivación e inteligencia emocional en Educación Física. Rev. Electrónica Interuniv. De Form. Del Profr. 2019, 22, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, D.Á.; Hawrylak, M.F. Impacto emocional de la actividad física: Emociones asociadas a la actividad física competitiva y no competitiva en educación primaria. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2022, 45, 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Rochín, D.M.; Berrueto, A.C. Estado de la investigación sobre inteligencia emocional y rendimiento deportivo. Rev. De Cienc. Del Ejerc. FOD 2022, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, V.H.D.; Mancha-Triguero, D.; Godoy, S.J.I.; Buñuel, P.S.L. Motivación, inteligencia emocional y carga de entrenamiento en función del sexo y categoría en baloncesto en edades escolares. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2022, 22, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez González, P.; Cecchini Estrada, J.A.; Méndez Giménez, A.; Sánchez Martínez, B. Motivación intrínseca, inteligencia emocional y autorregulación del aprendizaje: Un análisis multinivel. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Física Y Del Deporte 2021, 21, 235–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barwick, G.S.C.; Poyatos, M.C.; Fernández, J.D.M. Emotional intelligence and satisfaction with life in schoolchildren during times of pandemic. Espiral. Cuad. Del Profr. 2022, 15, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, C.I.; Jiménez, M.D.L.V.M. Rendimiento deportivo en atletas federados y su relación con autoestima, motivación e inteligencia emocional. Rev. De Psicol. Apl. Al Deporte Y Al Ejerc. Físico 2021, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychol. Rep. 2004, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Extremera, N.; Fernández, P. ¿Es la inteligencia emocional un adecuado predictor del rendimiento académico en estudiantes? In Proceedings of the III Jornadas de Innovación Pedagógica: Inteligencia Emocional, Una Brújula Para el Siglo XXI, Granada, Spain; 2011; pp. 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.C.; Balagué, G. The Development and Validation of the Perception of Success Questionnaire. In Proceedings of the European Federation of Sport Psychology Congress, Cologne, Germany; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, G.C.; Treasure, D.C.; Balagué, G. Achievement goals in sport: The development and validation of the Perception of Success Questionnaire. J. Sport Sci. 1998, 16, 337–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervelló Gimeno, E.; Escartí, A.; Balagué Gea, G. Relaciones entre la orientación de meta disposicional y la satisfacción con los resultados deportivos, las creencias sobre las causas de éxito en deporte y la diversión con la práctica. Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 1999, 8, 7–19. [Google Scholar]

- Granero-Gallegos, A.; Baena-Extremera, A.; Gomez-Lopez, M.; Abraldes, J.A. Estudio psicométrico y predicción de la importancia de la Educación Física a partir de las orientaciones de meta (“Perception of Success Questionnaire-POSQ”). Psicol. Reflexão E Crítica 2014, 27, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Papí Monzó, M.; García Martínez, S.; García-Jaén, M.; Ferriz Valero, A. Orientaciones de meta y necesidades psicológicas básicas en el desarrollo de la Expresión Corporal en educación primaria: Un estudio piloto. Retos Nuevas Tend. En Educ. Física Deporte Y Recreación 2021, 42, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, J.; Carcedo, R.J.; García, J.A. Climate, Orientation and Fun in Under-12 Soccer Players. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Física Y El Deporte 2022, 20, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. A general method for analysis of covariance structures. Biometrika 1970, 57, 239–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jöreskog, K.G. Identification and estimation in path analysis with unmeasured variables. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1469–1484. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cáceres-Alvarado, L.; Nieto-Gutiérrez, J. Desarrollo de un cuestionario tridimensional de metas de logro en deportes de conjunto. J. Behav. Health Soc. Issues 2013, 5, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelló Gimeno, E.; Martínez Galindo, C.; Ferriz Morell, R.; Moreno Murcia, J.A.; Moya Ramón, M. El papel del clima motivacional, la relación con los demás, y la orientación de metas en la predicción del” flow” disposicional en Educación Física. Rev. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2011, 20, 0165–0178. [Google Scholar]

- Biddle, S.; Cury, F.; Goudas, M.; Sarrazin, P.; Famose, J.P.; Durand, M. Development of scales to measure perceived physical education class climate: A cross-national project. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 1995, 65, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervelló, E.; Santos-Rosa, R. Un estudio exploratorio de los factores personales y situacionales relacionados con la ansiedad precompetitiva en tenistas de competición. Área de Psicología del Deporte y Control Motor – Rendimiento Deportivo. 2000, pp. 305–313. Available online: https://www.cienciadeporte.com/images/congresos/caceres/Rendimiento_deportivo/psicologia_deporte/1ansiedad.pdf (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- De Mesa, C.G.G.; Estrada, J.A.C.; Fernández, A.L.; González, A.V. Influencia del entorno social y el clima motivacional en el autoconcepto de las futbolistas asturianas. Aula Abierta 2010, 38, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Navas, L.; Soriano, J.; Holgado, F.; López, M. Las orientaciones de meta de los estudiantes y los deportistas: Perfiles motivacionales. Acción Psicológica 2012, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, J.A.; González, C.; López, J.; Brustad, R.J. Relación del clima motivacional percibido con la orientación de meta, la motivación intrínseca y las opiniones y conductas de fair play. Rev. Mex. De Psicol. 2005, 22, 469–479. [Google Scholar]

- De Cabo, S.; Carriedo, A.; González, C. Actitudes de Fair Play durante la práctica de fútbol en alumnado de Educación Primaria. J. Sport Health Res. 2022, 14, 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Cecchini, J.A.; González, C.; Montero, J. Participación en el deporte y fair play. Psicothema 2007, 19, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van de Pol, P.K.; Kavussanu, M. Achievement goals and motivational responses in tennis: Does the context matter? Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2011, 12, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amoroso, J.; Antunes, R.; Valente-dos-Santos, J.; Furtado, G.; Rebelo-Gonçalves, R. Dispositional Orientations in Competitive Ultimate Frisbee Athletes. Cuad. De Psicol. Del Deporte 2022, 22, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Borreguero, R. Perfil Motivacional y de Flow Disposicional de Jugadores Cadetes de Clubes Profesionales de Fútbol de Andalucía. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| 1 OTAREA | 2 O EGO | 3 AE | 4 CE | 5 RE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. O TAREA | 0.129 | 0.160 * | −0.043 | −0.070 | |

| 2. O EGO | −0.004 | −0.069 | 0.020 | ||

| 4. AE | 0.127 | 0.263 ** | |||

| 5. CE | 0.508 ** | ||||

| 6. RE |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mercader-Rubio, I.; Ángel, N.G.; Granero-Gallegos, A.; Ruiz, N.F.O.; Sánchez-López, P. Motivational Orientation in University Athletes: Predictions Based on Emotional Intelligence. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100397

Mercader-Rubio I, Ángel NG, Granero-Gallegos A, Ruiz NFO, Sánchez-López P. Motivational Orientation in University Athletes: Predictions Based on Emotional Intelligence. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):397. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100397

Chicago/Turabian StyleMercader-Rubio, Isabel, Nieves Gutiérrez Ángel, Antonio Granero-Gallegos, Nieves Fátima Oropesa Ruiz, and Pilar Sánchez-López. 2022. "Motivational Orientation in University Athletes: Predictions Based on Emotional Intelligence" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 10: 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100397

APA StyleMercader-Rubio, I., Ángel, N. G., Granero-Gallegos, A., Ruiz, N. F. O., & Sánchez-López, P. (2022). Motivational Orientation in University Athletes: Predictions Based on Emotional Intelligence. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 397. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100397