Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Urban studies do not sufficiently address how exactly culture is related to behavioral studies and more specifically the way men and women behave differently in urban public spaces.

- Gender studies and feminist geography—those negotiating gender roles, equal rights, and access to urban public spaces—are not adequately concerned with cultural influence on the relationships that men and women establish with urban public spaces.

- Cross-cultural models, which study behavioral differences, lack attention to gender differences in behavioral patterns.

2. Theories and Hypotheses

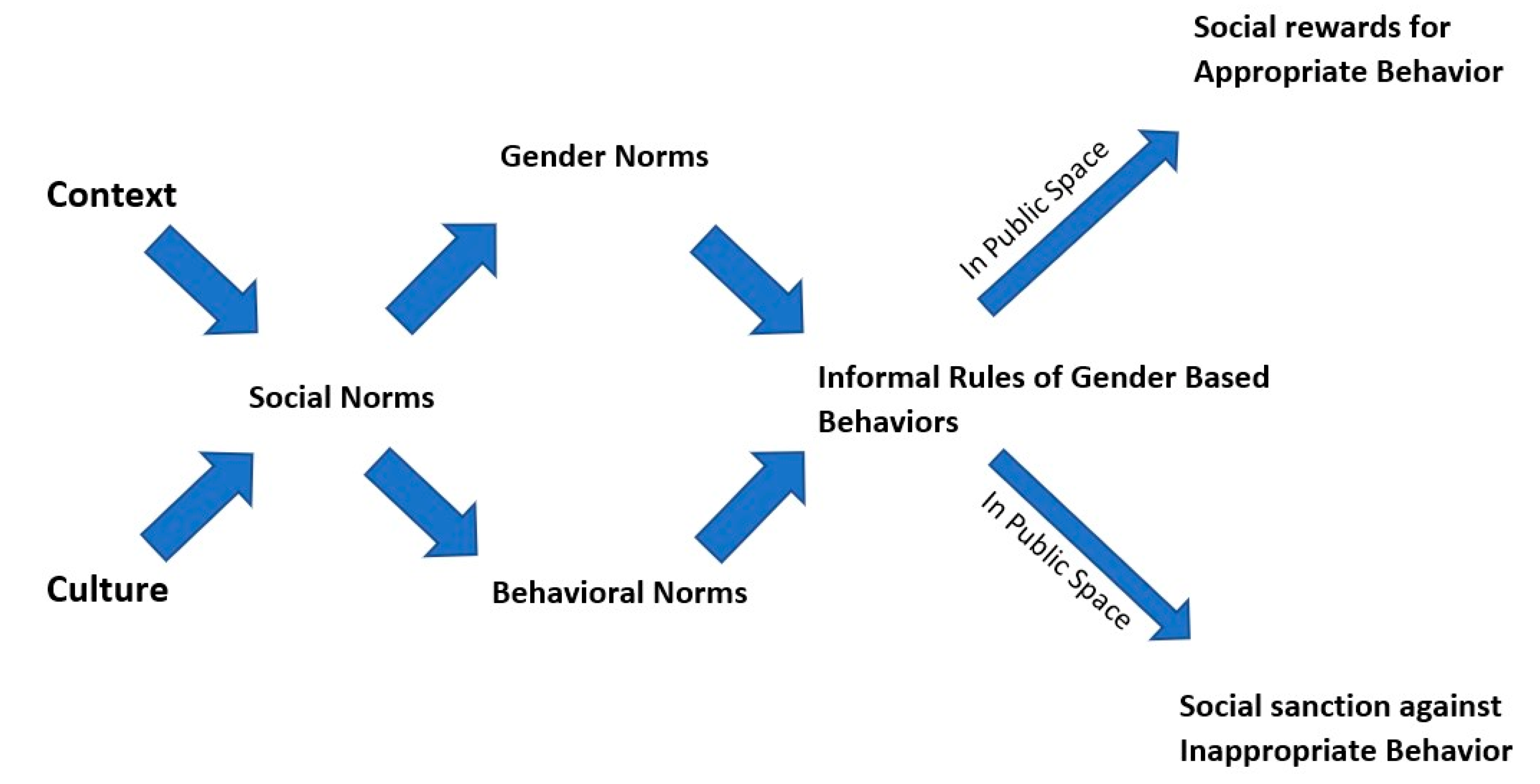

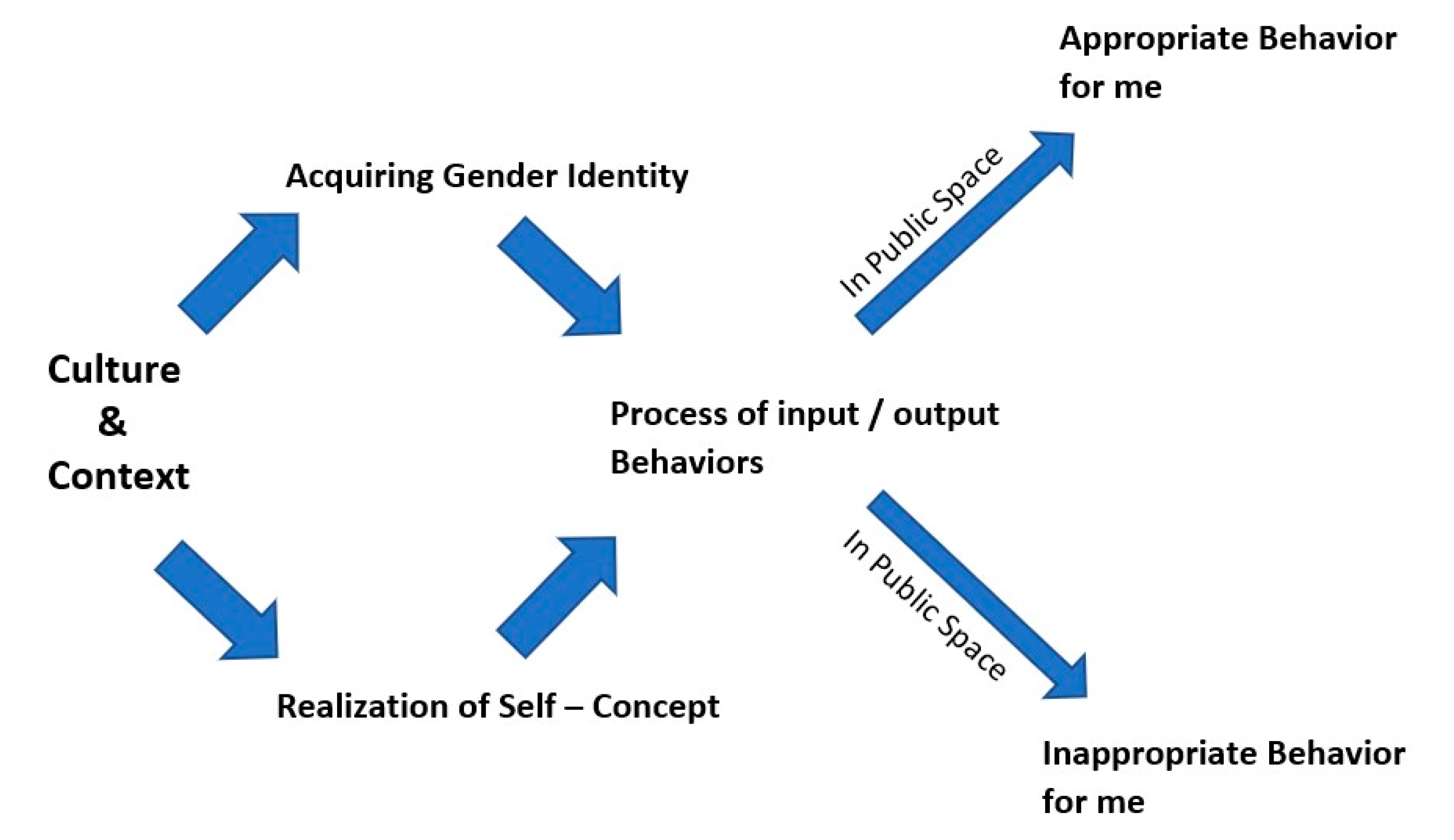

2.1. The Social Construction of Gender and Public Space Behavior

2.2. Social Cognitive Theory and Public Space Behavior

2.3. Culture, Gender, and Public Space Behavior in Traditional-Islamic Context

- Men and women should not look at each other directly.

- Men and women should be clean and honest.

- Women should cover themselves; they should conceal their beauty and makeup in the presence of strangers, lest they attract and seduce them.

2.4. Behavioral Intentions in Urban Public Spaces

3. Materials and Methods

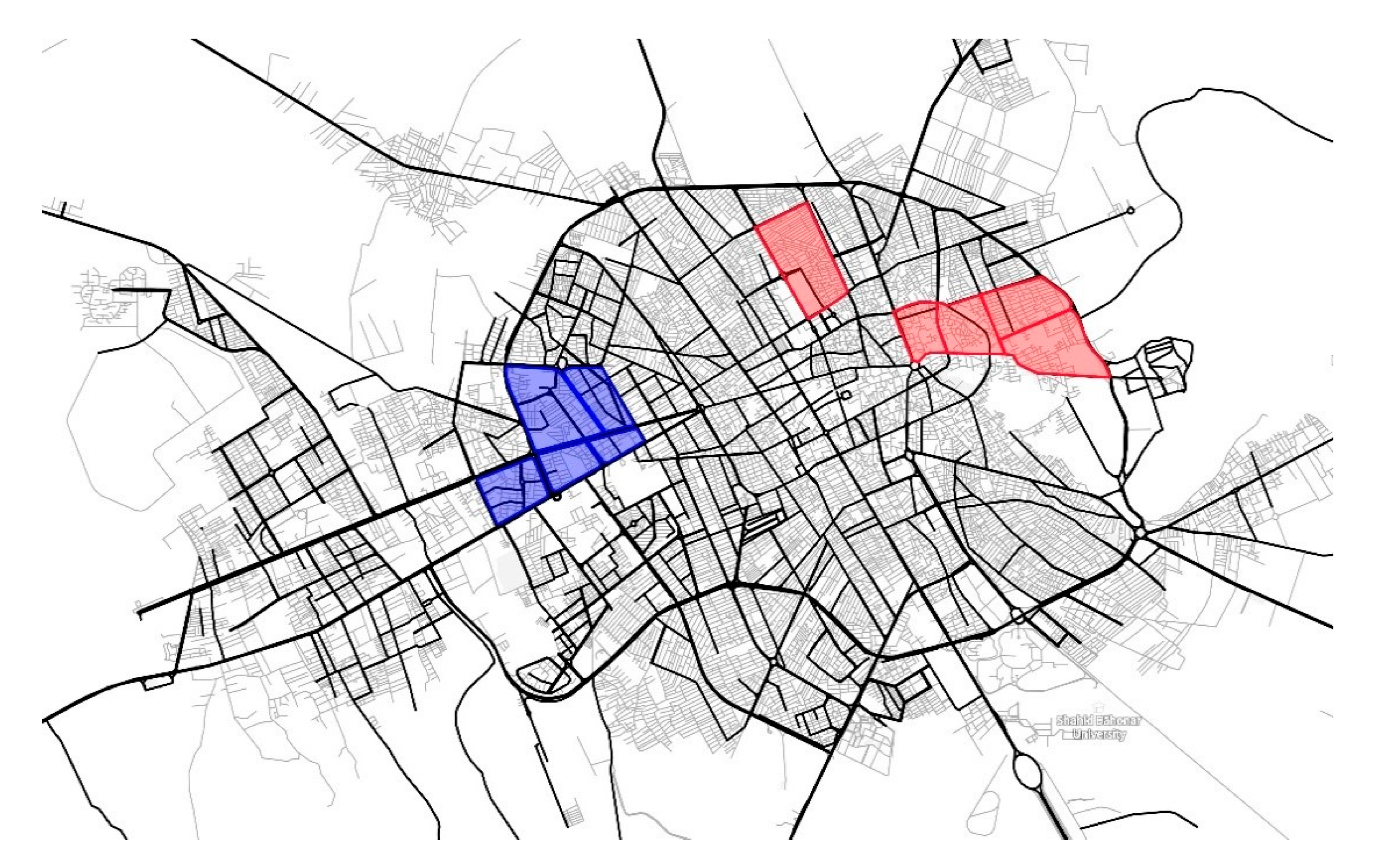

3.1. Case Study

3.2. Sample and Data Collection

3.3. Variables

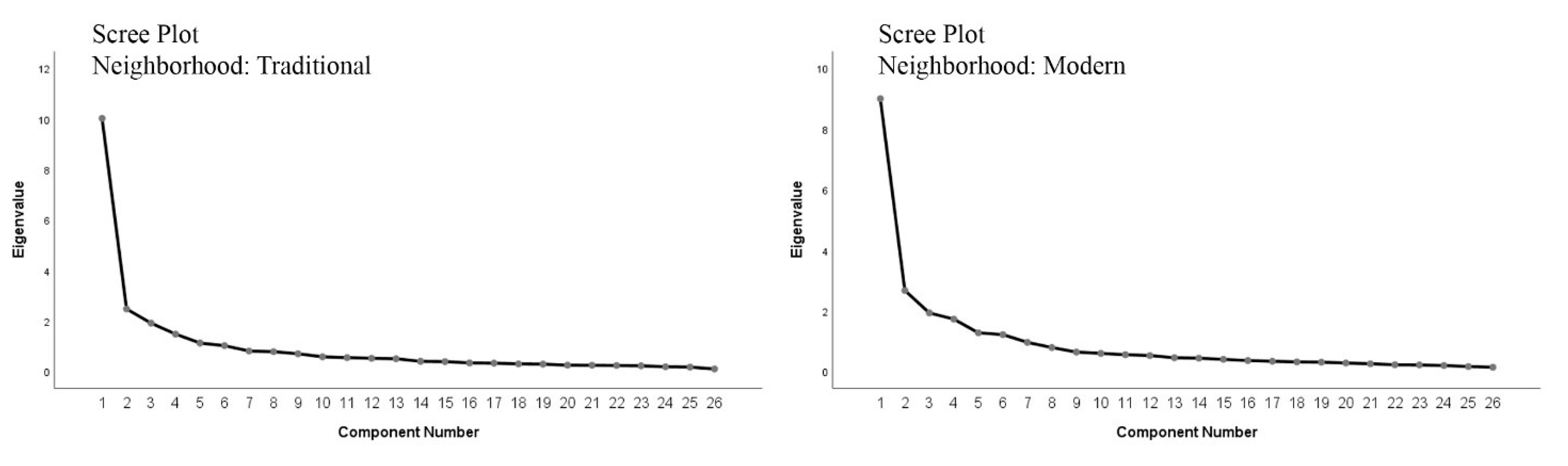

3.4. Data Validation

4. Results

4.1. Evaluating the Relationship between Culture and Behavior in Public Space

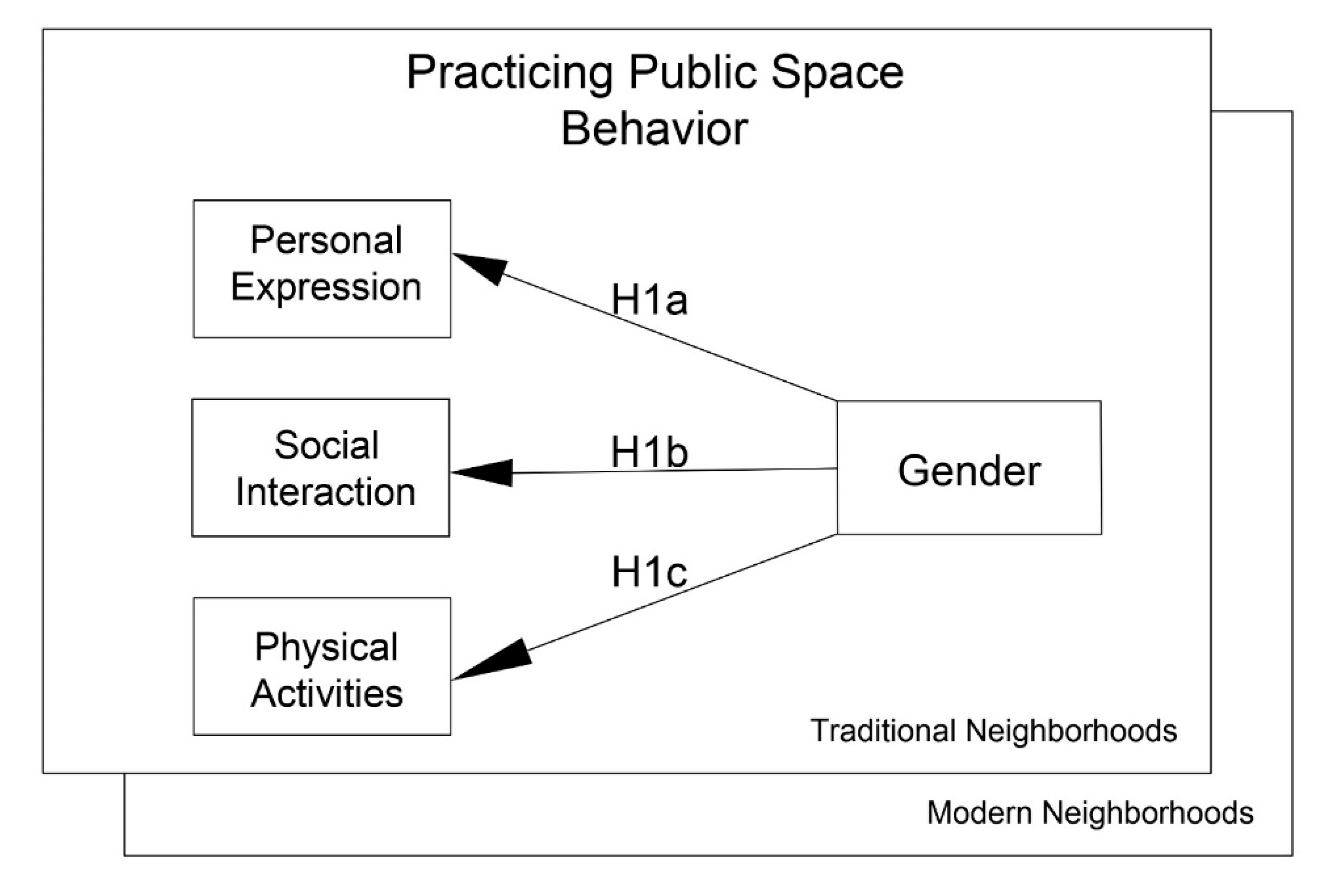

4.2. Gender’s Effect on Practicing Public Space Behaviors (Testing First Three Hypotheses)

4.3. Gender’s Relations with Behavioral Intentions in Urban Public Spaces (Testing Second Three Hypotheses)

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McDowell, L. Towards an Understanding of the Gender Division of Urban Space. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1983, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, D. Gender and urban space. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2014, 40, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondi, L.I.Z.; Rose, D. Constructing gender, constructing the urban: A review of Anglo-American feminist urban geography. Gend. Place Cult. 2003, 10, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bishawi, M.; Ghadban, S.; Jørgensen, K. Women’s behaviour in public spaces and the influence of privacy as a cultural value: The case of Nablus, Palestine. Urban Stud. 2017, 54, 1559–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Vetro, A.; Concha, P. Building safer public spaces: Exploring gender difference in the perception of safety in public space through urban design interventions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbar, J. Crisis in the Built Environment: The Case of the Muslim City; İnsan Yayınları: Istanbul, Turkey, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Beebeejaun, Y. Gender, urban space, and the right to everyday life. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 39, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scraton, S.; Watson, B. Gendered cities: Women and public leisure space in the ‘postmodern city’. Leis. Stud. 1998, 17, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, N. Mapping women in Tehran’s public spaces: A geo-visualization perspective. Gend. Place Cult. 2014, 21, 1285–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifé, A.C. Género, edad y diseño en un espacio público: El Parc dels Colors de Mollet del Vallés. In Espacios Públicos, Género y Diversidad. Geografías para unas Ciudades Inclusivas; García Ramon, M.D., Ortiz Guitart, A., Prats Ferret, M., Eds.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- García Ramon, M.D.; Ortiz Guitart, A.; Prats Ferret, M.E. La Via Júlia de Nou Barris: Un estudio cualitativo y de género de un espacio público en Barcelona. In Espacios públicos, Género y Diversidad. Geografías para unas Ciudades Inclusivas; García Ramon, M.D., Ortiz Guitart, A., Prats Ferret, M., Eds.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- Franck, K.; Paxson, L. Women and Urban Public Space. In Public Places and Spaces; Altman, I., Zube, E.H., Eds.; Plenum Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989; pp. 121–146. [Google Scholar]

- Peimani, N.; Kamalipour, H. Where gender comes to the fore: Mapping gender mix in urban public spaces. Spaces Flows Int. J. Urban ExtraUrban Stud. 2016, 8, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandogan, O.; Ilhan, B. Fear of Crime in Public Spaces: From the View of Women Living in Cities. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 2011–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, N.; Welch, E.W. Addressing fear of crime in public space: Gender differences in reaction to safety measures in train transit. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2491–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, J. Gender in Public Space: Policy Frameworks and the Failure to Prevent Street Harassment; Princeton University Senior Theses. Recuperado en. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.691.9803&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed on 24 April 2022).

- Whitzman, C. Building Inclusive Cities: Women’s Safety and the Right to the City; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Whitzman, C. Stuck at the front door: Gender, fear of crime and the challenge of creating safer space. Environ. Plan. A 2007, 39, 2715–2732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K. Constructing masculinity and women’s fear in public space in Irvine, California. Gend. Place Cult. A J. Fem. Geogr. 2001, 8, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, K. The ethic of care and women’s experiences of public space. J. Environ. Psychol. 2000, 20, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valentine, G. The geography of women’s fear. Area 1989, 21, 385–390. [Google Scholar]

- Pain, R.H. Social geographies of women’s fear of crime. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 1997, 22, 231–244. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela, H.; Pain, R. Revisiting fear and place: Women’s fear of attack and the built environment. Geoforum 2000, 31, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.B. Race, crime and social exclusion: A qualitative study of white women′s fear of crime in Johannesburg. Urban Forum 2002, 13, 53–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, C.G. Street harassment and the informal ghettoization of women. Harv. Law Rev. 1993, 106, 517–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuncer, S. Going public: Women’s narratives of everyday gendered violence in modern Turkey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Knowledge and Politics in Gender and Women’s Studies, Ankara, Turkey; 2015; pp. 904–913. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, A. Politics of presence: Women’s safety and respectability at night in Mumbai, India. Gend. Place Cult. 2018, 25, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce Güney, Y. Gender and urban space: An examination of a small Anatolian city. A| Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2014, 11, 153–172. [Google Scholar]

- Güney, Y.İ.; Kubat, A.S. Gender and urban space: The case of Sharjah, UAE. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12462/8967 (accessed on 11 August 2022).

- Rendell, J.; Penner, B.; Borden, I. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction; Psychology Press: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, N. What qualitative GIS maps tell and don′t tell: Insights from mapping women in Tehran′s public spaces. J. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 31, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir-Ebrahimi, M. Public spaces in enclosure, PAGES 2004, February, pp. 3-10. Available online: https://www.pagesmagazine.net/en/articles/public-spaces-in-enclosure (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Amir-Ebrahimi, M. Conquering enclosed public spaces. Cities 2006, 23, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, N. Modernizing the Public Space: Gender Identities, Multiple Modernities, and Space Politics in Tehran. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Missouri, Kansas, MO, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Fenster, T. Space for gender: Cultural roles of the forbidden and the permitted. Environ. Plan. D Soc. Space 1999, 17, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumcu, S.; Duzenli, T.; Özbilen, A. Social Construction of Gender in an Open Public Space. In Proceedings of the 4th International Congress on Livable Environments and Architecture, Trabzon, Turkey, 9–11 July 2009; pp. 717–728. [Google Scholar]

- Bagheri, N. Tehran’s subway: Gender, mobility, and the adaptation of the ‘proper’Muslim woman. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2019, 20, 304–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackstone, A.M. Gender Roles and Society. In Human Ecology: An Encyclopedia of Children, Families, Communities, and Environments; Miller, J.R., Lerner, R.M., Schiamberg, L.B., Eds.; ABC-CLIO: Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Domosh, M.; Seager, J. Putting Women in Place: Feminist Geographers Make Sense of The World; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Sharistanian, J. Beyond the Public-Domestic Dichotomy: Contempory Perspectives on Women′s Public Lives; Praeger Pub Text: Westport, CT, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- García Ramon, M.D.; Ortiz Guitart, A.; Prats Ferret, M.E. Género, discriminación y subversión en el espacio público: Una aproximación desde el barrio de Ca n’Anglada. In Espacios públicos, género y diversidad. Geografías para unas ciudades inclusivas; García Ramon, M.D., Ortiz Guitart, A., Prats Ferret, M., Eds.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2014; pp. 93–111. [Google Scholar]

- Palacios Vivar, D.C. Uso y acceso diferenciado al espacio público desde la perspectiva de género: El Parque de la Madre del cantón Cuenca. Master’s Thesis, Universidad De Cuenca, Cuenca, Ecuador, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cárcamo, C.B. Mujeres, ocio y apropiación del espacio público. Una aproximación al fenómeno del ocio desde la geografía feminista en la ciudad de Valparaíso. Master’s Thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, G. The creation of patriarchy. Vol. 1. Women and History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1986; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Saegert, S. Masculine Cities and Feminine Suburbs: Polarized Ideas, Contradictory Realities. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 1980, 5, S96–S111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Geel, A. Separate or together? Women-only public spaces and participation of Saudi women in the public domain in Saudi Arabia. Contemp. Islam 2016, 10, 357–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, P. Women outdoors: Destabilizing the public/private dichotomy. Companion Fem. Geogr. 2005, 322–334. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, N. Renegotiating gender and sexuality in public and private spaces. In BodySpace; Routledge: London, UK, 1996; pp. 135–152. [Google Scholar]

- Krenichyn, K. Women and physical activity in an urban park: Enrichment and support through an ethic of care. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domosh, M. Geography and gender: Home, again? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1998, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, D. Gendered spaces and women’s status. Sociol. Theory 1993, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. The right to the gendered city: Different formations of belonging in everyday life. J. Gend. Stud. 2005, 14, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenster, T. Gender and human rights: Implications for planning and development. In Gender, Planning and Human Rights; Routledge: London, UK, 1999; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Ramon, M.D.; Ortiz, A.; Prats, M. Urban planning, gender and the use of public space in a peripherial neighbourhood of Barcelona. Cities 2004, 21, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huning, S. Deconstructing space and gender? Options for «gender planning». Les cahiers du CEDREF. Centre d’enseignement, d’études et de recherches pour les études feminists 2014, 21. Available online: https://journals.openedition.org/cedref/973 (accessed on 3 September 2022). [CrossRef]

- Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. The Fight for Public Space: When Personal Is Political; South Caucasus Regional Office of the Heinrich Boell Foundation: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Read. Psychol. Cult. 2011, 2, 2307-0919.1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G.; Hofstede, G.J.; Minkov, M. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind; Mcgraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G.J. Culture’s causes: The next challenge. Cross Cult. Manag. 2015, 22, 545–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, B. The People Make the Place. Pers. Psychol. 1987, 40, 437–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neville, L.; Schneider, B. Why is it so Hard to Change a Culture? It’s the People. Inspir. Future OD Real. Our Work. 2021, 53, 41–46. [Google Scholar]

- Infante-Vargas, D.; Boyer, K. Gender-based violence against women users of public transport in Saltillo, Coahuila, Mexico. J. Gend. Stud. 2022, 31, 216–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villora, B.; Yubero, S.; Navarro, R. Associations between Feminine Gender Norms and Cyber Dating Abuse in Female Adults. Behav. Sci. 2019, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lata, L.N.; Walters, P.; Roitman, S. The politics of gendered space: Social norms and purdah affecting female informal work in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Gend. Work. Organ. 2021, 28, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Sánchez, G.; Olmo-Sánchez, M.I.; Maeso-González, E. Challenges and Strategies for Post-COVID-19 Gender Equity and Sustainable Mobility. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegarty, B. Governing Nonconformity: Gender Presentation, Public Space, and the City in New Order Indonesia. J. Asian Stud. 2021, 80, 955–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, L.; Messaoudene, M. Gendered and Gender-Neutral Character of Public Places in Algeria. Quaest. Geogr. 2021, 40, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Lieshout, M.; Aarts, N. Youth and Immigrants’ Perspectives on Public Spaces. Space Cult. 2008, 11, 497–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, B.E.; Christensen, R.K. Public Service Motivation: A Test of the Job Attraction–Selection–Attrition Model. Int. Public Manag. J. 2010, 13, 155–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, J.; Gergen, K.J. Toward a New Psychology of Gender; Psychology Press: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- DeLamater, J.D.; Hyde, J.S. Essentialism vs. social constructionism in the study of human sexuality. J. Sex Res. 1998, 35, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Variations on sex and gender: Beauvoir, Wittig, and Foucault. PRAXIS Int. 1998, 5, 505–516. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bohan, J.S. Regarding Gender: Essentialism, Constructionism, and Feminist Psychology. Psychol. Women Q. 1993, 17, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tischler, H.L. Cengage Advantage Books: Introduction to Sociology; Cengage Learning: Mason, OH, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, M.; Brullet, C. Rosa y azul. Las Transmisión de los Géneros en la Escuela Mixta; Instituto de la Mujer: Madrid, España, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Tomé, A. Estrategias para elaborar proyectos coeducativos en las escuelas. Atlánticas-Rev. Int. Estud. Fem. 2017, 2, 89–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lucas-Palacios, L.; García-Luque, A.; Delgado-Algarra, E.J. Gender Equity in Initial Teacher Training: Descriptive and Factorial Study of Students’ Conceptions in a Spanish Educational Context. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Luque, A. La LOMCE bajo una mirada de género/s: Avances o retrocesos en el s. XXI? Rev. Educ. Política Y Soc. 2016, 100–124. [Google Scholar]

- Subirats, M.; Tomé González, A. Pautas de Observación para el Análisis del Sexismo en el Ámbito Educativo; Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, ICE: Barcelona, Spain, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Arnot, M.; Araujo, H.; Deliyanni-Kouimtzi, K.; Rowe, G.; Tome, A. Teachers, Gender and the Discourses of Citizenship. Int. Stud. Sociol. Educ. 1996, 6, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Best, D.L.; Williams, J.E. Gender and Culture. In The Handbook of Culture and Psychology; Matsumoto, D., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2001; pp. 195–219. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, D.G.; Perry, L.C. Observational learning in children: Effects of sex of model and subject’s sex role behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1975, 31, 1083–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leaper, C.; Friedman, C.K. The Socialization of Gender. In Handbook of Socialization: Theory and Research; Grusec, J.E., Hastings, P.D., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 561–587. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, T.L.; Zerbinos, E. Gender roles in animated cartoons: Has the picture changed in 20 years? Sex Roles 1995, 32, 651–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emons, P.; Wester, F.; Scheepers, P. “He Works Outside the Home; She Drinks Coffee and Does the Dishes” Gender Roles in Fiction Programs on Dutch Television. J. Broadcast. Electron. Media 2010, 54, 40–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jin, X.; Whitson, R. Young women and public leisure spaces in contemporary Beijing: Recreating (with) gender, tradition, and place. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2014, 15, 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, R.; Harper, C.; Brodbeck, S.; Page, E. Social norms, gender norms and adolescent girls: A brief guide. In The Knowledge to Action Resources Series; ODI: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchieri, C. Norms in the wild: How to Diagnose, Measure, and Change Social Norms; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Heise, L. Social Norms; GSDRC Professional Development Reading, no. 31; University of Birmingham: Birmingham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer, D.R.; Kipp, K. Developmental Psychology: Childhood and Adolescence, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’brien, M.; Peyton, V.; Mistry, R.; Hruda, L.; Jacobs, A.; Caldera, Y.; Huston, A.; Roy, C. Gender-role cognition in three-year-old boys and girls. Sex Roles 2000, 42, 1007–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Banerjee, R. Gender Identity and the Development of Gender Roles; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- West, A. A brief review of cognitive theories in gender development. Behav. Sci. Undergrad. J. 2015, 2, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K.; Bandura, A. Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychol. Rev. 1999, 106, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, C.L.; Ruble, D.N.; Szkrybalo, J. Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychol. Bull. 2002, 128, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, J.C. Social identity. In Encyclopedia of Psychology; Kazdin, A.E., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; Volume 7, pp. 341–343. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, S.L. Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychol. Rev. 1981, 88, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronk, L. Culture’s Influence on Behavior: Steps Toward a Theory. Evol. Behav. Sci. 2016, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, M.A.S.A. The Qur’an; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Azani, M.; Zal, H. گردشگرى زنان فرصت ها و تنگناها از دیدگاه اسلام (Women as tourist, opportunities and limitations from Islam perspective). فصلنامه علمی-پژوهشی اطلاعات جغرافیایی سپهر 2011, 20, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Motahari, A. مسائل فقهی در آثار استاد مطهری [Ethical issues in words of Motahari]. J. Res. Humanit. 2000, 12, 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- ISNA. The way women spend their free times from past till today [شیوه های گذراندن اوقات فراغت زنان از دیروز تا امروز]. ISNA: Iranian Students’ News Agency, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaiee, M.S. فضاهای فراغتی شهری و زنانگیهای جدید [Urban leisure spaces and new femininity]. فصلنامه علوم اجتماعی 2016, 23, 63–92. [Google Scholar]

- Predelli, L.N. Interpreting gender in Islam: A case study of immigrant Muslim women in Oslo, Norway. Gend. Soc. 2004, 18, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.G.; Wood, W. Self-regulation of gendered behavior in everyday life. Sex Roles 2010, 62, 635–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniehotta, F. An experimental test of the theory of planned behavior. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2009, 1, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albarracin, D.; Johnson, B.T.; Fishbein, M.; Muellerleile, P.A. Theories of reasoned action and planned behavior as models of condom use: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drnovsek, M.; Erikson, T. Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Econ. Bus. Rev. Cent. South-East. Eur. 2005, 7, 55. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E. The role of national cultural values within the theory of planned behaviour. In The Customer is NOT Always Right? Marketing Orientationsin a Dynamic Business World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; p. 813. [Google Scholar]

- Statistical-Center-of-Iran. Population of the Country in Urban and Rural Areas, By Sex and Province 2016. Available online: https://irandataportal.syr.edu/census/census-2016 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- Bartlett, J.E.; Kotrlik, J.W.; Higgins, C.C. Organizational research: Determining appropriate sample size in survey research appropriate sample size in survey research. Inf. Technol. Learn. Perform. J. 2001, 19, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, M. Blurring the boundaries: Public space and private life. In Public Space Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 26–33. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, W.; Malibari, A. Saudi Women and Vision 2030: Bridging the Gap? Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahdavi, P. Passionate uprisings: Young people, sexuality and politics in post-revolutionary Iran. Cult. Health Sex. 2007, 9, 445–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R.S.; Giacomin, O.; Janssen, F. Entrepreneurial Perceptions and Intentions: The Role of Gender and Culture. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 465–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrington, D. Confirmatory Factor Analysis; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Girden, E.R. ANOVA: Repeated Measures; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Experimental Designs Using ANOVA; Thomson/Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, T. Gender, group composition, cooperation, and self-efficacy in computer studies. J. Educ. Comput. Res. 1996, 15, 125–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, D.; Ortegren, M. Gender differences in ethics research: The importance of controlling for the social desirability response bias. J. Bus. Ethics 2011, 103, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namy, L.L.; Nygaard, L.C.; Sauerteig, D. Gender Differences in Vocal Accommodation: The Role of Perception. J. Lang. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 21, 422–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheeran, P. Intention—Behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. Eur. Rev. Soc. Psychol. 2002, 12, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ANOVA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | ||||||||

| Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| Hypothesis 1a: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Personal Expression | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 6.269 | 6.269 | 6.668 | 0.011 | 28.779 | 28.779 | 31.940 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 172.974 | 0.940 | 211.737 | 0.901 | |||||

| Total | 179.2 | 240.5 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 1b: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Social Interaction | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 15.647 | 15.647 | 18.507 | 0.000 | 34.936 | 34.936 | 44.995 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 155.565 | 0.845 | 182.467 | 0.776 | |||||

| Total | 171.2 | 217.4 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 1c: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Physical Activities | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 0.966 | 0.966 | 1.198 | 0.275 | 6.713 | 6.713 | 8.879 | 0.003 |

| Within Groups | 147.646 | 0.807 | 176.911 | 0.756 | |||||

| Total | 148.6 | 183.6 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 2a: Personal Expressions and level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 15.741 | 15.741 | 17.100 | 0.000 | 23.856 | 23.856 | 26.810 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 170.298 | 0.921 | 209.103 | 0.890 | |||||

| Total | 186.0 | 232.9 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 2b: Social Interactions and the level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 26.851 | 26.851 | 24.342 | 0.000 | 33.171 | 33.171 | 30.088 | 0.000 |

| Within Groups | 204.064 | 1.103 | 259.078 | 1.102 | |||||

| Total | 230.9 | 292.2 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 2c: Physical Activities and the level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups Modern–traditional | 2.545 | 2.545 | 5.699 | 0.018 | 4.683 | 4.683 | 8.976 | 0.003 |

| Within Groups | 82.609 | 0.447 | 122.610 | 0.522 | |||||

| Total | 85.1 | 127.2 | |||||||

| ANOVA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Neighborhoods | Modern Neighborhoods | ||||||||

| Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| Hypothesis 1a: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Personal Expression | Between Groups: male–female | 8.498 | 8.498 | 10.058 | 0.002 | 0.333 | 0.333 | 0.339 | 0.561 |

| Within Groups | 163.907 | 0.845 | 220.803 | 0.981 | |||||

| Total | 172.4 | 221.1 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 1b: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Social Interaction | Between Groups: male–female | 8.207 | 8.207 | 11.089 | 0.001 | 2.448 | 2.448 | 2.833 | 0.094 |

| Within Groups | 143.577 | 0.740 | 194.455 | 0.864 | |||||

| Total | 151.7 | 196.9 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 1c: Perceived behavioral restrictions in Physical Activities | Between Groups: male–female | 6.337 | 6.337 | 8.054 | 0.005 | 1.468 | 1.468 | 1.903 | 0.169 |

| Within Groups | 151.074 | 0.787 | 173.483 | 0.771 | |||||

| Total | 157.4 | 174.9 | |||||||

| ANOVA | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Neighborhoods | Modern Neighborhoods | ||||||||

| Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | Sum of Squares | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ||

| Hypothesis 2a: Personal Expressions and level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups: male–female | 0.438 | 0.438 | 0.473 | 0.492 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.066 | 0.798 |

| Within Groups | 179.727 | 0.926 | 199.674 | 0.884 | |||||

| Total | 180.1 | 199.7 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 2b: Social Interactions and the level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups: male–female | 0.932 | 0.932 | 0.824 | 0.365 | 1.049 | 1.049 | 0.973 | 0.325 |

| Within Groups | 219.380 | 1.131 | 243.762 | 1.079 | |||||

| Total | 220.3 | 244.8 | |||||||

| Hypothesis 2c: Physical Activities and the level of behavioral appropriateness | Between Groups: male–female | 0.337 | 0.337 | 0.544 | 0.462 | 0.055 | 0.055 | 0.146 | 0.703 |

| Within Groups | 120.000 | 0.619 | 85.219 | 0.377 | |||||

| Total | 120.3 | 85.2 | |||||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jalalkamali, A.; Doratli, N. Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100388

Jalalkamali A, Doratli N. Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman. Behavioral Sciences. 2022; 12(10):388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100388

Chicago/Turabian StyleJalalkamali, Aida, and Naciye Doratli. 2022. "Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman" Behavioral Sciences 12, no. 10: 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100388

APA StyleJalalkamali, A., & Doratli, N. (2022). Public Space Behaviors and Intentions: The Role of Gender through the Window of Culture, Case of Kerman. Behavioral Sciences, 12(10), 388. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs12100388