The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: The Italian Validation of Two Instruments for Meaning-Focused Assessments of Bereavement

Abstract

1. Background

2. The Research

Aims and Research Questions

- Determine whether the Italian versions of the Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale (ISLES) and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief (ICSG) are reliable and valid, as reflected by their convergence with related measures;

- Evaluate the impact of socio-demographic variables on the ISLES and ICSG;

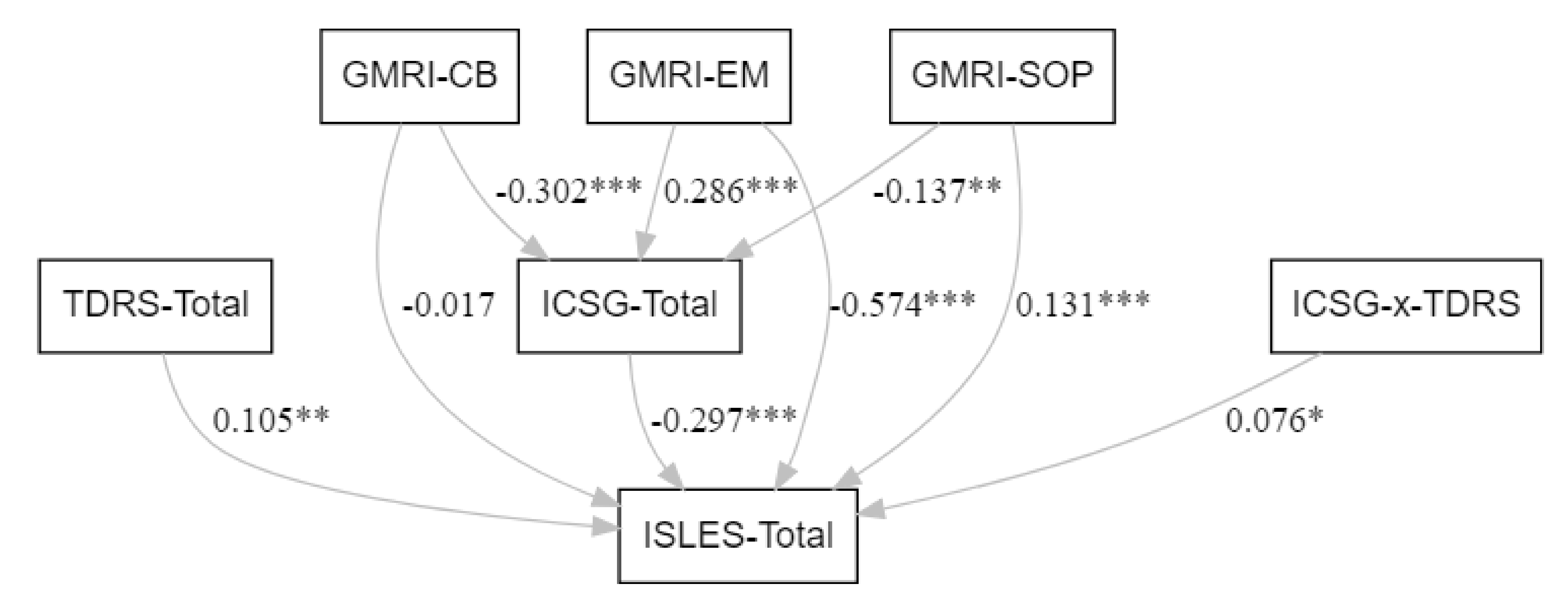

- Test whether the relation between meaning reconstruction after loss and the degree of integration of the loss into the mourner’s meaning system is mediated by spiritual struggle;

- Test whether the representation of death as a form of passage or annihilation moderates the relation between spiritual struggle and the integration of the loss experience.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Procedure

3.3. Ethical Considerations

3.4. Measures

3.5. Data Analyses

3.5.1. Validation of the Instruments

3.5.2. Impact of Socio-Demographic Variables on ICSG and ISLES

3.5.3. Path Model

4. Results

4.1. Validation of the Instruments

4.2. Impact of Socio-Demographic Variables on ICSG and ISLES

4.3. Path Model

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Research Limitations and Future Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Bowlby, J. Attachment and Loss: Separation; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1973; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Stud. 2019, 43, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Burke, L.; Mackay, M.; Stringer, J. Grief therapy and the reconstruction of meaning: From principles to practice. J. Contemp. Psychother. 2010, 40, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Bregoli, J.; Pompele, S.; Maccarini, A. Social Support in Perinatal Grief and Mothers’ Continuing Bonds: A Qualitative Study with Italian Mourners. Affilia 2020, 35, 485–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Franco, C.; Palazzo, L.; Iacona, E.; Zamperini, A.; Wieser, M.A. The endless grief in waiting: A qualitative study of the relationship between ambiguous loss and anticipatory mourning amongst the relatives of missing persons in Italy. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Sansonetto, G.; Ronconi, L.; Rodelli, M.; Baracco, G.; Grassi, L. Meaning of life, repre-sentation of death, and their association with psychological distress. Palliat Support Care 2018, 16, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I. Psicologia del lutto e del morire: Dal lavoro clinico alla death education [The psychology of death and mourning: From clinical work to death education]. Psicoter. Sci. Umane 2016, 50, 229–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, J.; Neimeyer, R.A. Loss, grief, and the search for significance: Toward a model of meaning reconstruction in bereavement. J. Constr. Psychol. 2006, 19, 31–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Constructions of death and loss: Evolution of a research program. PCTP 2004, 1, 8–20. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, D.; Mendes, I.; Gonçalves, M.; Neimeyer, R.A. Innovative moments in grief therapy: Reconstructing meaning following perinatal death. Death Stud. 2012, 36, 795–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Currier, J.M.; Holland, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A. Sense-making, grief, and the experience of violent loss: Toward a mediational model. Death Stud. 2006, 30, 403–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, T.M.; Tofthagen, C.S.; Buck, H.G. Complicated grief: Risk factors, protective factors, and interventions. J. Soc. Work End--Life Palliat. Care 2020, 16, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Currier, J.M. Grief therapy: Evidence of efficacy and emerging directions. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009, 18, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Berman, J.S. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for the bereaved: A comprehensive quantitative review. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.R.; Neimeyer, R.A. Does grief counseling work? Death Stud. 2003, 27, 765–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A. Searching for the meaning of meaning: Grief therapy and the process of reconstruction. Death Stud. 2000, 24, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Young-Eisendrath, P. Assessing a Buddhist treatment for bereavement and loss: The Mustard Seed Project. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Sands, D.C. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement. Grief Bereave. Contemp. Soc. 2021, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawthorne, D.M.; Youngblut, J.M.; Brooten, D. Parent spirituality, grief, and mental health at 1 and 3Months after their infant’s/Child’s death in an intensive care unit. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2016, 31, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganzevoort, R.R.; Falkenburg, H. Stories beyond life and death: Spiritual experiences of continuity and discontinuity among parents who loose a child. J. Empir. Theol. 2012, 25, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, L.A.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Holland, J.M.; Dennard, S.; Oliver, L.; Shear, M.K. Inventory of complicated spiritual grief: Development and validation of a new measure. Death Stud. 2014, 38, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Maciejewski, P.K.; Reynolds, C.F.; Bierhals, A.J.; Newsom, J.T.; Fasiczka, A.; Frank, E.; Doman, J.; Miller, M. Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Res. 1995, 59, 65–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmassi, C.; Shear, M.K.; Massimetti, G.; Wall, M.; Mauro, C.; Gemignani, S.; Conversano, C.; Dell’Osso, L. Validation of the Italian version Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG): A study comparing CG patients versus bipolar disorder, PTSD and healthy controls. Compr. Psychiatry 2014, 55, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Field, N.P.; Filanosky, C. Continuing Bonds, Risk Factors for Complicated Grief, and Ad-justment to Bereavement. Death Stud. 2010, 34, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, M.L.; Grossi, G.M.; Zaccarello Greco, R.; Tineri, M.; Slavic, E.; Altomonte, A.; Palummieri, A. Adaptation and validation of the “Continuing Bond Scale” in an Italian context. An instrument for studying the persistence of the bond with the deceased in normal and abnormal grief. Int. J. Psychoanal. Edu. 2016, 8, 37–52. [Google Scholar]

- Prigerson, H.G.; Horowitz, M.J.; Jacobs, S.C.; Parkes, C.M.; Aslan, M.; Goodkin, K.; Raphael, B.; Marwit, S.J.; Wortman, C.; Neimeyer, R.A.; et al. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, M.L.; Tineri, M.; Zaccarello, G.; Grossi, G.; Altomonte, A.; Slavic, E.; Palummieri, A.; Greco, R. Adattamento e validazione del questionario “PG-13” prolonged grief nel contesto italiano. Riv. Ital. Cure Palliat. 2015, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer, R.A.; Woodward, M.; Pickover, A.; Smigelsky, M. Questioning our questions: A constructivist technique for clinical supervision. J. Constr. Psychol. 2016, 29, 100–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine J. 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambleton, R.K. The next generation of the ITC Test Translation and Adaptation Guidelines. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2001, 17, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, J.M.; Neimeyer, R.A.; Milman, E. The Grief and Meaning Reconstruction Inventory (GMRI): Initial Validation of a New Measure. Death Stud. 2015, 39, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Antonellini, M.; Ronconi, L.; Biancalani, G.; Neimeyer, R.A. Spirituality and Meaning-Making in Bereavement: The Role of Social Validation. J. Loss Trauma 2021, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.M.; Currier, J.M.; Coleman, R.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale (ISLES): Development and initial validation of a new measure. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2010, 17, 325–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Ancona, D.; Ronconi, L. The Ontological Representation of Death: A Scale to Measure the Idea of Annihilation Versus Passage. OMEGA 2015, 71, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psych Bull. 1990, 107, 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.W. MUTMUM PC: User’s Guide; Department of Psychology, Ohio State University: Columbus, OH, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling and more Version 0.5-12 (BETA). J. Stat. Soft. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currier, J.M.; Holland, J.M.; Rozalski, V.; Thompson, K.L.; Rojas-Flores, L.; Herrera, S. Teaching in violent communities: The contribution of meaning made of stress on mental health and burnout. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2013, 20, 254–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthal, W.G.; Burke, L.A.; Neimeyer, R.A. Religious coping and meaning-making following the loss of a loved one. Couns. Spiritual. 2011, 30, 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni, I.; Falletti, S.; Visintin, E.P.; Ronconi, L.; Zamperini, A. Il volontariato nelle cure palliative: Religiosità, rappresentazioni esplicite della morte e implicite di Dio tra deumanizzazione e burnout [Volunteering in palliative care: Religiosity, explicit representations of death and implicit representations of God between dehumanization and burnout]. Psicol. Della Salut. 2016, 2, 27–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Visintin, E.P.; Capozza, D.; Carlucci, M.C.; Shams, M. The implicit Image of God: God as Reality and Psychological Well-Being. J. Sci. Study Relig. 2016, 55, 174–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Corso, L.; De Carlo, A.; Carluccio, F.; Colledani, D.; Falco, A. Employee burnout and positive dimensions of well-being: A latent workplace spirituality profile analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0242267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgeard, M.; Beard, C.; Shayani, D.; Silverman, A.L.; Tsukayama, E.; Björgvinsson, T. Predictors of affect following discharge from partial hospitalization: A two-week ecological momentary assessment study. Psychol. Med. 2021, 51, 1157–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L.; Zamperini, A. Pet Loss and Representations of Death, Attachment, Depression, and Euthanasia. Anthrozoös 2017, 30, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Putnam, R.D. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. Am. Sociol. Rev. 2010, 75, 914–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J. Ontological flooding and continuing bonds. Contin. Bonds Bereave. 2017, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testoni, I.; Di Lucia Sposito, D.; De Cataldo, L.; Ronconi, L. Life at all costs? Italian social representations of end-of-life decisions after president Napolitano’s speech—margin notes on withdrawing artificial nutrition and hydration. Nutr. Ther. Metab. 2015, 32, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomarken, A.; Roth, A.; Holland, J.; Ganz, O.; Schachter, S.; Kose, G.; Ramirez, P.M.; Allen, R.; Nelson, C.J. Examining the role of trauma, personality, and meaning in young prolonged grievers. Psycho-Oncology 2011, 21, 771–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Scale | Model | Chi-Square 1 | df | CFI | TLI | RMSEA | Delta Chi-Square | Delta df | p-Value | Delta CFI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICSG | 1-factor | 1068.762 | 135 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.141 | 338.025 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.008 |

| 2-factors | 730.737 | 134 | 0.986 | 0.984 | 0.113 | |||||

| ISLES | 1-factor | 385.035 | 104 | 0.991 | 0.989 | 0.088 | 84.29 | 1 | <0.001 | −0.003 |

| 2-factors | 300.745 | 103 | 0.994 | 0.992 | 0.074 |

| Variable | M | SD | Range | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.GMRI_CB | 3.85 | 0.62 | 1–5 | - | |||||||

| 2.GMRI_PG | 3.1 | 0.67 | 1–5 | 0.43 * | - | ||||||

| 3.GMRI_SOP | 3.08 | 0.97 | 1–5 | 0.11 | 0.04 | - | |||||

| 4.GMRI_EM | 2.67 | 0.78 | 1–5 | 0.23 * | 0.20 * | −0.31 * | - | ||||

| 5.GMRI_VL | 3.65 | 0.71 | 1–5 | 0.34 * | 0.64 * | 0.06 | 0.13 | - | |||

| 6.TDRS | 18.43 | 6.44 | 6–30 | −0.44 * | −0.12 | −0.09 | 0.02 | −0.12 | - | ||

| 7.ICSG | 22.77 | 18.15 | 0–72 | −0.25 * | −0.08 | −0.26 * | 0.26 * | −0.01 | 0.43 * | - | |

| 8.ISLES | 61.66 | 11.72 | 16–80 | −0.11 | −0.14 | 0.38 * | −0.70 * | −0.11 | −0.03 | −0.42 * | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neimeyer, R.A.; Testoni, I.; Ronconi, L.; Biancalani, G.; Antonellini, M.; Dal Corso, L. The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: The Italian Validation of Two Instruments for Meaning-Focused Assessments of Bereavement. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110149

Neimeyer RA, Testoni I, Ronconi L, Biancalani G, Antonellini M, Dal Corso L. The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: The Italian Validation of Two Instruments for Meaning-Focused Assessments of Bereavement. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(11):149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110149

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeimeyer, Robert A., Ines Testoni, Lucia Ronconi, Gianmarco Biancalani, Marco Antonellini, and Laura Dal Corso. 2021. "The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: The Italian Validation of Two Instruments for Meaning-Focused Assessments of Bereavement" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 11: 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110149

APA StyleNeimeyer, R. A., Testoni, I., Ronconi, L., Biancalani, G., Antonellini, M., & Dal Corso, L. (2021). The Integration of Stressful Life Experiences Scale and the Inventory of Complicated Spiritual Grief: The Italian Validation of Two Instruments for Meaning-Focused Assessments of Bereavement. Behavioral Sciences, 11(11), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110149