A Study on the Causes and Effects of Stressful Situations in Tourism for Japanese People

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1. What are the negative psychological impacts (the negative feelings) of tourism as perceived by local residents?

- RQ2. What are the causes of negative psychological impacts?

- RQ3. What are the strategies that local residents use to cope with negative psychological impacts?

- RQ4. What are the effects or outcomes of the coping strategies used?

2. Literature Review

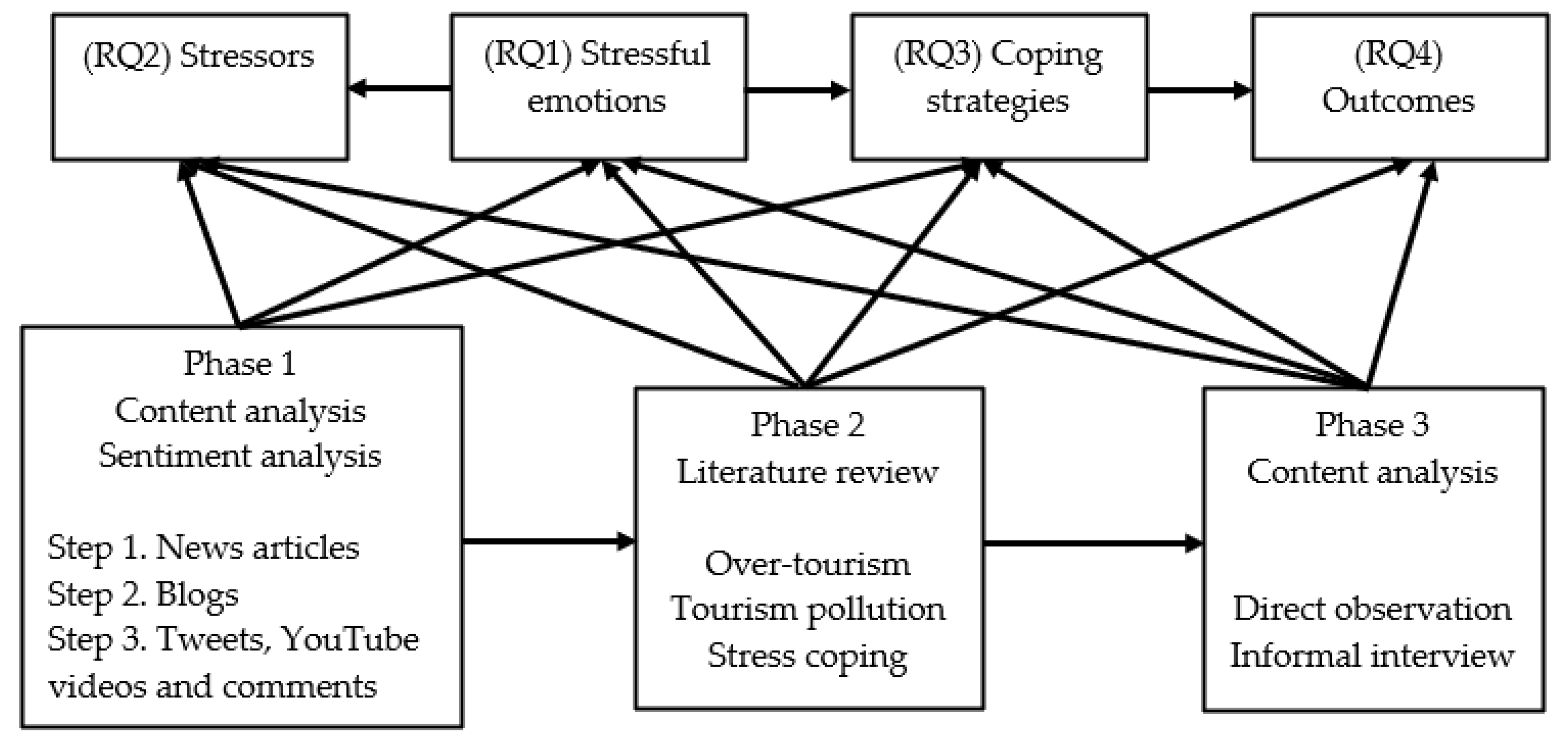

3. Methods

3.1. The First Phase of Data Collection and Analysis

3.1.1. The First Step of Data Collection

3.1.2. The Second Step of Data Collection

3.1.3. The Third Step of Data Collection

3.1.4. The Analysis of the First Phrase’s Data

3.2. The Second and Third Phases of Data Collection and Analysis

3.3. Limitations and Merits of the Methods

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Negative Feelings and Their Causes

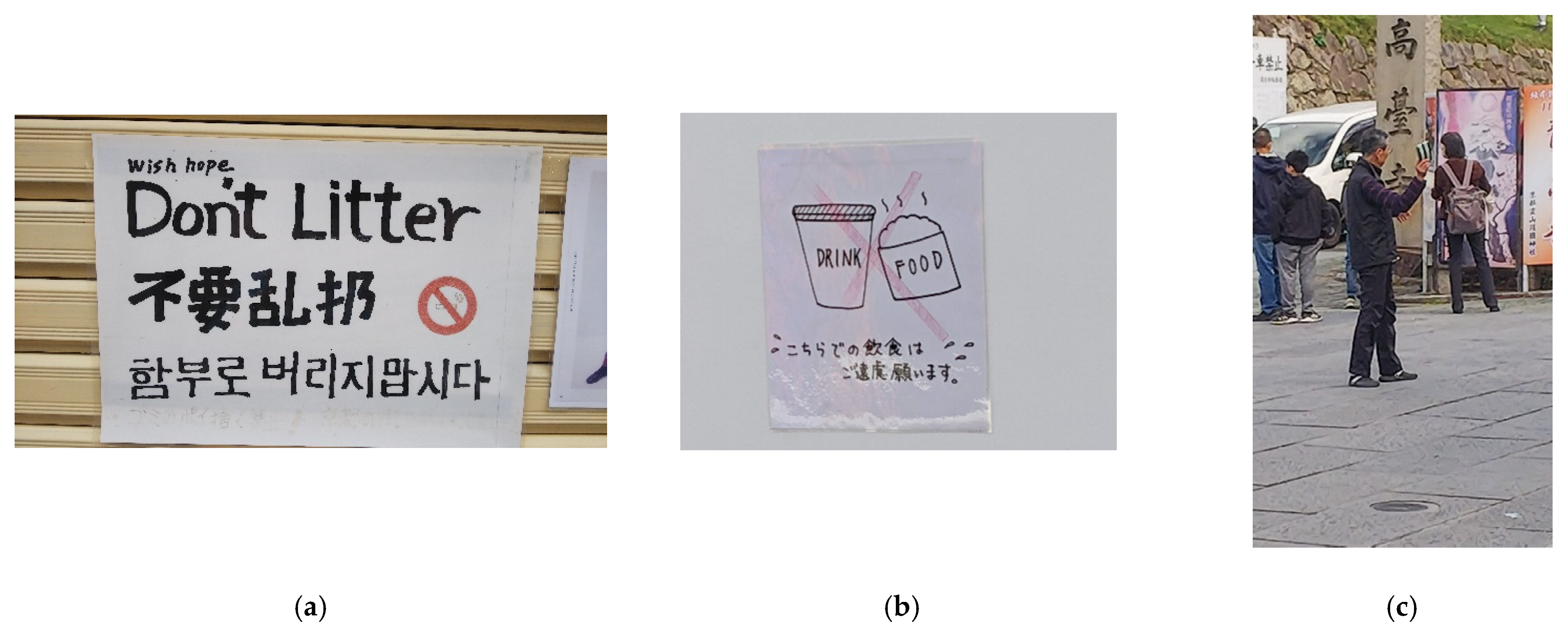

4.2. Coping Strategies and Their Effects

5. Implications of the Results

5.1. Theoretical Implications

5.2. Practical Implications

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tervo-Kankare, K.; Kaján, E.; Saarinen, J. Costs and benefits of environmental change: Tourism industry’s responses in Arctic Finland. Tour. Geogr. 2018, 20, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bramwell, B. Heritage protection and tourism development priorities in Hangzhou, China: A political economy and governance perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.D.; Bressan, A.; O’Shea, M.; Krajsic, V. Perceived Benefits and Challenges to Wine Tourism Involvement: An International Perspective. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2015, 17, 66–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. Residents’ Perceptions of the Impact of Cultural Tourism on Urban Development: The Case of Gwangju, Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 15, 405–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-C.; Petrick, J.F.; Shahvali, M. Tourism Experiences as a Stress Reliever: Ex-amining the effects of tourism recovery experiences on life satisfaction. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, S.; Khalifah, Z.; Mardani, A.; Streimikiene, D.; Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1061–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, C.-K.; Liu, Y.; Kang, S.; Dai, A. The Role of Perceived Smart Tourism Technology Experience for Tourist Satisfaction, Happiness and Revisit Intention. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, A.; Schmücker, D. Understanding and overcoming negative impacts of tourism in city destinations: Conceptual model and strategic framework. J. Tour. Future 2017, 3, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbaiwa, J.E. Poverty or riches: Who benefits from the booming tourism industry in Botswana? J. Contemp. Afr. Stud. 2017, 35, 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Kang, Y. Why do residents in an overtourism destination develop anti-tourist attitudes? An exploration of residents’ experience through the lens of the community-based tourism. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2020, 25, 858–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Moran, C.; Godwyll, J. Does tourism really cause stress? A natural experiment utilizing ArcGIS Survey123. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Lesar, L.; Spencer, D.M. Clarifying the Interrelations of Residents’ Perceived Tourism-Related Stress, Stressors, and Impacts. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau-Vadell, J.B.; Taño, D.G.; Díaz-Armas, R. Economic crisis and residents’ perception of the impacts of tourism in mass tourism destinations. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 7, 68–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godovykh, M.; Ridderstaat, J. Health outcomes of tourism development: A longitudinal study of the impact of tourism arrivals on residents’ health. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 17, 100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vogt, C.A. Residents’ Perceptions of Stress Related to Cruise Tourism Development. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2017, 14, 527–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Spencer, D.M.; Prayag, G. Tourism impacts, emotions and stress. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 75, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.; Jun, H.M.; Walker, M.; Drane, D. Evaluating the perceived social impacts of hosting large-scale sport tourism events: Scale development and validation. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, T.; Adu-Ampong, E.A. Residents with camera: Exploring tourism impacts through participant-generated images. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.-H.; Cheng, C.-W. Job stress, coping strategies, and burnout among hotel industry supervisors in Taiwan. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 21, 1337–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, S.H.; Kerr, J.H. Stress and emotions at work: An adventure tourism guide’s experiences. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tsaur, S.-H.; Tang, Y.-Y. Job stress and well-being of female employees in hospitality: The role of regulatory leisure coping styles. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2012, 31, 1038–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, E.J.; Vogt, C.A.; DeShon, R.P. A stress and coping framework for understanding resident responses to tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2015, 48, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, C. Domestic Tourism in Japan-Statistics & Facts. Statista. 2020. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/6858/domestic-tourism-in-japan/ (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Japan National Tourism Organization [JNTO]. Trends in Visitor Arrivals to Japan. Japan Tourism Statistics. 2020. Available online: https://statistics.jnto.go.jp/en/graph/#graph--inbound--travelers--transition (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Jang, K.; Sakamoto, K.; Funck, C. Dark tourism as educational tourism: The case of ‘hope tourism’ in Fukushima, Japan. J. Heritage Tour. 2021, 16, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapoval, V.; Wang, M.C.; Hara, T.; Shioya, H. Data Mining in Tourism Data Analysis: Inbound Visitors to Japan. J. Travel Res. 2018, 57, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Usui, R.; Wei, X.; Funck, C. The power of social media in regional tourism development: A case study from Ōkunoshima Island in Hiroshima, Japan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 2060–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.-S.; Nozu, K.; Cheung, T.O.L. Tourism and natural disaster management process: Perception of tourism stakeholders in the case of Kumamoto earthquake in Japan. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 1864–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Kelemen, M.; Tresidder, R. Post-disaster tourism: Building resilience through community-led approaches in the aftermath of the 2011 disasters in Japan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1766–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martini, A.; Minca, C. Affective dark tourism encounters: Rikuzentakata after the 2011 Great East Japan Disaster. Soc. Cult. Geogr. 2021, 22, 33–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hinch, T.; Ito, E. Sustainable Sport Tourism in Japan. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2018, 15, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Progano, R.N. Spiritual (walking) tourism as a foundation for sustainable destination development: Kumano-kodo pilgrimage, Wakayama, Japan. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 24, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, L.K.; Lohr, J.M. Stress and Stress Management—Research and Applications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Schönfeld, P.; Brailovskaia, J.; Bieda, A.; Zhang, X.C.; Margraf, J. The effects of daily stress on positive and negative mental health: Mediation through self-efficacy. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2016, 16, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linton, S.J. Does work stress predict insomnia? A prospective study. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2004, 9, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wacogne, C.; Lacoste, J.P.; Guillibert, E.; Hugues, F.C.; Le Jeunne, C. Stress, Anxiety, Depression and Migraine. Cephalalgia 2003, 23, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowden, P.; Matthews, G.; Watson, B.; Biggs, H. The relative impact of work-related stress, life stress and driving environment stress on driving outcomes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1332–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Struthers, C.W.; Perry, R.P.; Menec, V.H. An Examination of the Relationship Among Academic Stress, Coping, Motivation, and Performance in College. Res. High. Educ. 2000, 41, 581–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitetta, L.; Anton, B.; Cortizo, F.; Sali, A. Mind-Body Medicine: Stress and Its Impact on Overall Health and Longevity. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1057, 492–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasoolimanesh, S.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Jaafar, M.; Ramayah, T. Urban vs. rural destinations: Residents’ perceptions, community participation and support for tourism development. Tour. Manag. 2017, 60, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Huang, J. Effects of Destination Social Responsibility and Tourism Impacts on Residents’ Support for Tourism and Perceived Quality of Life. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 42, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diedrich, A.; Aswani, S. Exploring the potential impacts of tourism development on social and ecological change in the Solomon Islands. Ambio 2016, 45, 808–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Iwasaki, Y.; Mackay, K.; Mactavish, J. Gender-Based Analyses of Coping with Stress among Professional Managers: Leisure Coping and Non-Leisure Coping. J. Leis. Res. 2005, 37, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavas, U.; Karatepe, O.M.; Babakus, E. Does hope buffer the impacts of stress and exhaustion on frontline hotel employees’ turnover intentions? Tour. Int. Interdiscip. J. 2013, 61, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David, A.; Huurdeman, H.C. Web Archive Search as Research: Methodological and Theoretical Implications. Alexandria 2014, 25, 93–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulock, H.L. Research Design: Descriptive Research. J. Pediatr. Oncol. Nurs. 1993, 10, 154–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, R.; Jankel-Elliott, N. Using ethnography in strategic consumer research. Qual. Mark. Res. 2003, 6, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kozinets, R.V. The Field behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities. J. Mark. Res. 2002, 39, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, W.; Stepchenkova, S. User-Generated Content as a Research Mode in Tourism and Hospitality Applications: Topics, Methods, and Software. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2015, 24, 119–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B. Sentiment Analysis: Mining Opinions, Sentiments, and Emotions; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Abe, Y. The nuclear power debate after Fukushima: A text-mining analysis of Japanese newspapers. Contemp. Jpn. 2015, 27, 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuhara, T.; Ishikawa, H.; Okada, M.; Kato, M.; Kiuchi, T. Newspaper coverage before and after the HPV vaccination crisis began in Japan: A text mining analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kassarjian, H.H. Content Analysis in Consumer Research. J. Consum. Res. 1977, 4, 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducate, L.C.; Lomicka, L.L. Adventures in the blogosphere: From blog readers to blog writers. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. 2008, 21, 9–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyland, K.; Zou, H. In the frame: Signalling structure in academic articles and blogs. J. Pragmat. 2020, 165, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Yu, C.; Meng, W.; Chowdhury, A. Effective keyword search in relational databases. In Proceedings of the 2006 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 563–574. [Google Scholar]

- Baratta, A. Read Critically; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xun, J.; Reynolds, J. Applying netnography to market research: The case of the online forum. J. Target. Meas. Anal. Mark. 2010, 18, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SimilarWeb. Top Websites Ranking. SimilarWeb. 2020. Available online: https://www.similarweb.com/top-websites/japan/ (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- Amarasekara, I.; Grant, W.J. Exploring the YouTube science communication gender gap: A sentiment analysis. Public Underst. Sci. 2019, 28, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazard, A.J.; Scheinfeld, E.; Bernhardt, J.M.; Wilcox, G.B.; Suran, M. Detecting themes of public concern: A text mining analysis of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Ebola live Twitter chat. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2015, 43, 1109–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, M.M. More than words: Social networks’ text mining for consumer brand sentiments. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 4241–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, N.; Ayvaz, S. Sentiment analysis on Twitter: A text mining approach to the Syrian refugee crisis. Telemat. Inform. 2018, 35, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thelwall, M. Social media analytics for YouTube comments: Potential and limitations. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2018, 21, 303–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppermann, M. Triangulation—A methodological discussion. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2000, 2, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saumure, K.; Given, L.M. Data saturation. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Quali-Tative Research Methods; Given, L.M., Ed.; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 195–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenker, S.; Kock, F. The coronavirus pandemic—A critical discussion of a tourism research agenda. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E.; Wirtz, D.; Tov, W.; Kim-Prieto, C.; Choi, D.-W.; Oishi, S.; Biswas-Diener, R. New Well-being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Soc. Indic. Res. 2010, 97, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodds, R.; Butler, R. The phenomena of overtourism: A review. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2019, 5, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagase, Y.; Uchiyama, M.; Kaneita, Y.; Li, L.; Kaji, T.; Takahashi, S.; Konno, M.; Mishima, K.; Nishikawa, T.; Ohida, T. Coping strategies and their correlates with depression in the Japanese general population. Psychiatry Res. 2009, 168, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, T. Assessing Coping With Interpersonal Stress: Development and Validation of the Interpersonal Stress Coping Scale in Japan. Int. Perspect. Psychol. Res. Pract. Consult. 2013, 2, 100–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, Y.; Kaneita, Y.; Itani, O.; Nakagome, S.; Jike, M.; Ohida, T. Relationship between stress coping and sleep disorders among the general Japanese population: A nationwide representative survey. Sleep Med. 2017, 37, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, J.E. Harmony, Empathy, Loyalty, and Patience in Japanese Children’s Literature. Soc. Stud. 2008, 99, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japantimes. Keep Growing Inbound Tourism. Japantimes. 2019. Available online: https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2019/01/06/editorials/keep-growing-inbound-tourism/ (accessed on 23 September 2020).

- Kyodo News. Abe Declares Coronavirus Emergency over in Japan. Kyodo News. 2020. Available online: https://english.kyodonews.net/news/2020/05/a1f00cf165ae-japan-poised-to-end-state-of-emergency-over-coronavirus-crisis.html (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Belal, H.M.; Shirahada, K.; Kosaka, M. Value Co-creation with Customer through Recursive Approach Based on Japanese Omotenashi Service. Int. J. Bus. Adm. 2013, 4, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milano, C.; Novelli, M.; Cheer, J.M. Overtourism and tourismphobia: A jour-ney through four decades of tourism development, planning and local concerns. Tour. Plan. Dev. 2019, 16, 353–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerva, K.; Palou, S.; Blasco, D.; Donaire, J.A. Tourism-philia versus tourism-phobia: Residents and destination management organization’s publicly expressed tourism perceptions in Barcelona. Tour. Geogr. 2019, 21, 306–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Sheeran, P.; Pilato, M. Over-tourism and the fall of Venice as a destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2018, 9, 374–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.; Zaman, M.; Lorey, T. Limitations of Trexit (tourism exit) as a solution to overtourism. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2019, 11, 566–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCool, S.F.; Lime, D.W. Tourism Carrying Capacity: Tempting Fantasy or Useful Reality? J. Sustain. Tour. 2001, 9, 372–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, K.; Uchida, S. Quality Matters More Than Quantity: Asymmetric Temperature Effects on Crop Yield and Quality Grade. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2016, 98, 1195–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Tourism Agency. We Have Formulated the “Tourism Vision Realization Program 2018” (Action Program for Realization of Tourism Vision 2018)! Japan Tourism Agency. 2018. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/kankocho/en/kouhou/page01_000312.html (accessed on 23 September 2020).

| Types of Data | Number |

|---|---|

| News articles | 26 |

| Blogs | 7 |

| YouTube videos (comments) | 8 (70) |

| Tweets | 121 |

| Original in Japanese | Translation in English |

|---|---|

| 憤りを感じている | Indignant |

| 痛みを感じている | Pain |

| イライラしている | Frustrated |

| 苛立っている | Frustrated |

| うんざりしている | Fed up, tired |

| 怒っている | Angry |

| 悲しい | Sad |

| 苦悩している | Distressed |

| 苦しめられる | Distressed |

| 怖い | Scared, fleftened |

| ストレス | Stressed |

| 心配している | Concerned, worried |

| 疲れている | Tired |

| 辛い | Bitter |

| 懐かしい | Nostalgic |

| 疲弊している | Exhausted |

| 不安 | Anxious, insecure |

| 不平不満 | Discontented |

| 不満 | Dissatisfied, discontented |

| 辟易している | Tired, overwhelmed |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nghiêm-Phú, B.; Shibuya, K. A Study on the Causes and Effects of Stressful Situations in Tourism for Japanese People. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110143

Nghiêm-Phú B, Shibuya K. A Study on the Causes and Effects of Stressful Situations in Tourism for Japanese People. Behavioral Sciences. 2021; 11(11):143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110143

Chicago/Turabian StyleNghiêm-Phú, Bình, and Kazuki Shibuya. 2021. "A Study on the Causes and Effects of Stressful Situations in Tourism for Japanese People" Behavioral Sciences 11, no. 11: 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110143

APA StyleNghiêm-Phú, B., & Shibuya, K. (2021). A Study on the Causes and Effects of Stressful Situations in Tourism for Japanese People. Behavioral Sciences, 11(11), 143. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110143