1. Introduction

Reviewing the literature on trust, Fink, Harms, and Mölleringin [

1] defined trust as the willingness to be vulnerable in a situation of risk; and confident positive expectations among group members based on attributes of a trustee, see also [

2,

3]. Furthermore, trustworthiness is defined as the attributes of a trustee that inspire trust [

4]. Almost all scholars share the view that trust is multidimensional regarding its components or dimensions constituting evidence of trustworthiness, e.g., [

5,

6]. Beyond the agreement on this definition of trust and trustworthiness, literature on this topic has been defined as being poorly integrated, widely confused and not unitary, lacking coherence, and facing a large number of challenging problems, e.g., [

7]. Particularly, a predominant need remains to establish “the multi-dimensionality of trust” more concretely and contextually and solve the problems related to which dimensions of trustworthiness are distinct yet related [

8]. Indeed, a complete comprehension of trust requires a depth of understanding of the components of trustworthiness. This study was intended as a preliminary exploration of the multidimensional nature of trust in the higher educational context.

Authority Trustworthiness: Competence and Benevolence

In the review of McEvily and Tortoriello [

7], authors found that the state of the art of trust measurement is rudimentary, highly fragmented, and characterized by weak evidence in support of construct validity and limited consensus on trustworthiness dimensions. They argued that it remains unclear whether or when a distinction among trustworthiness dimensions can be effectively distinguished statistically and/or meaningfully. Whipple, Griffins, and Daugherty [

8] also revealed a fragmentation in the literature in the way that trustworthiness is theorized and measured. Although a remarkable amount of the relevant trust literature utilized direct and unidimensional measures (e.g., “Do you trust X?”), many researchers identified trustworthiness more specifically, recognizing its components in many different operationalizations. For instance, Lui and Ngo [

9] described competence and goodwill trust as two fundamental dimensions of trustworthiness in organizations. In their study, competence included characteristics like good reputation and resources of capital and labor. Goodwill trust included characteristics like fairness in negotiations and faith. However, other researchers gave different conceptualizations of the trustworthiness components. McAllister [

10] theorized a cognitive form of trustworthiness and an affective form of trustworthiness. Specifically, cognition-based trust was defined as individuals’ beliefs about others’ reliability, integrity, honesty, fairness, dependability, professional credentials, and competences. Affect-based trust reflected a referent’s responsibility, care, and concern for others’ welfare. Furthermore, the conceptualization of trustworthiness could be diversified depending on the context of study and the referent of trust. For instance, the dimensions of trustworthiness may differ if we refer to trust in peers or to trust in authorities. Indeed, Hoy & Tschannen-Moran [

11] indicated that, even if every facet of trustworthiness is relevant, its effective weight could depend on the trustee, the trustor, the nature of their relationship, and the general context.

Overall, despite this variety in theorizing and measuring components of trustworthiness, many researchers, e.g., [

12,

13,

14,

15], shared the assumption that trustworthiness should include at least two dimensions. One dimension would capture the benevolence or the “will-do” component of trustworthiness [

15] also described as character-based trust [

16]. The other dimension captures the competence or the “can-do” aspect of trustworthiness [

15,

16], also described as ability-based trust [

17] and competence-based trust [

12,

13]. Barki and colleagues [

15] tested a Boolean non-linear relationship model between the characteristics of trustworthiness and trusting behaviors. They argued that the “can-do” component describes whether the authority has the skills and abilities needed to act in an appropriate fashion, whereas the “will-do” component captures the extent to which an authority wants to help a person independent of any profit motive. In the “can-do” frame, competence has become one of the most commonly discussed components of trustworthiness; it generally captures the knowledge and skills needed to do a specific job, e.g., [

12,

13,

16,

18,

19]. Sometimes, competence also refers to interpersonal competence (i.e., the skills applied in dealing with and relating to other people) [

16] or to a person’s expertise and capacity to select helpful and accurate information [

13]. In school settings, Chory [

20] defined competence as authority expertise and knowledge in the subjects that he/she is teaching that are related to students’ sense of interactional justice. In the same context, Tschannen-Moran and Hoy [

21] defined competence as the facet of trust that captured the authority skills, knowledge, and expertise needed to enhance students’ learning and well-being. Hoy and Tschannen-Moran [

11] also described competence as the skills needed in situations when a person is dependent on another and that can fulfill an expectation of trust. In the “will-do” frame, benevolence was described among the most important facets of trustworthiness, particularly in the educational field [

21]. Benevolence is defined as the assurance that the other will not exploit someone

’s vulnerability or take excessive advantage of someone, even when the opportunity is available [

22]. Hoy & Tschannen-Moran [

11] also defined benevolence as the confidence that another party has the other’s best interests at heart and will protect them by demonstrating caring, sincerity, discreteness, fairness, goodwill, empathy, a lack of opportunism, equitability, and altruism. Chory [

20] defined caring as students’ perception of authority interest in students’ needs and welfare that is related to the sense of procedural and interactional classroom justice. Thus, pertaining to educational contexts, researchers share the idea that competence and benevolence are two important antecedents of trust perceptions in authorities [

21].

However, PytlikZillig, Hamm, Shockley, Herian, Neal, Kimbrough, Tomkins, and Bornstein [

23] argued that relatively few empirical studies have investigated the trust-dimensionality in institutional contexts, such as university. Furthermore, little empirical work has systematically compared trust-relevant dimensions (e.g., determining the number of components of trust and which are the most similar to each other) or weighed their relations under different conditions and contexts. They found that from a measurement perspective, it may be the case that some of these conceptually-distinct components of trust are statistically or practically indistinguishable. In the university context, authors [

24] manipulated and explored the effects of perceived authority’s benevolence and competence on students’ attitudes. Results showed that students from both Italy and the United States viewed a caring, competent authority as most trustworthy, and an uncaring, incompetent authority as most untrustworthy. In their quantitative study, the manipulation of competence had effects on students’ perceptions of a lecturer’s competence and smaller but significant effects on perception of the same lecturer’s good intentions. The manipulation of benevolence had effects on students’ perceptions of the lecturer’s good intentions but also a smaller effect on perceptions of his competence. This pattern of results suggested that competence and benevolence judgments are interrelated and cognitively integrated in the undergraduate students’ view. However, the quantitative studies presented above have not discussed possible differences in the qualitative content of the students’ perception of competence and benevolence. A qualitative approach could reveal something not observed. In this view, a qualitative approach has been defined as an important approach to fully understand the contents of the experience of university students [

25,

26].

Therefore, in this investigation, we aim to explore in depth the students’ representations of a faculty member’s competence and benevolence, starting from the students’ own original words and priorities. In the literature, the meaning of competence and benevolence is often unclear and overlapping. By directly asking what students had in mind when thinking of competence and benevolence, we aimed to investigate whether the overlapping present in literature could also be spotted in the representation shared by students. Do students have in mind two separate components of trustworthiness, i.e., competence and benevolence? Or do they have in mind one single dimension, with overlapping competence and benevolence characteristics? We expected students to have an overlapping mixed representation of benevolence and competence, often switching words when referring to one or to the other. We expected to find in the students’ words a mono-dimensional nature of authority trustworthiness within the university context. We also aimed to investigate the content of the subcategories of competence and benevolence as they emerged from the voices of the undergraduate students themselves. In the data analysis, we were ready to locate in the data the subcomponents present in the literature, but we were also sensitive to the priorities and dimensions spontaneously emerging from students’ associations. Do students refer to the same subcategories for competence and benevolence? Or do they have in mind specific characteristics for competence and others specific to benevolence? We expected students would confuse competence with benevolence and vice versa, and in this sense, they would use the same characteristics to describe both concepts. In this sense, we aimed to perform an exploratory qualitative study to answer our research questions concerning the overlapping between competence and benevolence.

3. Results

When students evaluate a lecturer in terms of his/her competence, they take into consideration their previous experiences with both competent and incompetent lecturers. For this reason, we decided to analyze together the data corpus produced via the stimulus word “competent lecturer” and via the stimulus word “incompetent lecturer.” This way, we hoped to have a more comprehensive picture of the students’ view of the lecturer’s competence, both in the negative and positive side. The same reasoning applies when judging the lecturer’s benevolence. We analyzed together the dictionaries relating to “benevolent” and “malevolent” lecturer. The analyses were run separately for competent/incompetent lecturer, on the one hand, and for benevolent/malevolent lecturer on the other hand. For clarity, results are presented divided into the representation of the “competent/incompetent lecturer” and the representation of the “benevolent/malevolent lecturer”.

3.1. Representation of the Lecturer: the “Can-Do” and the “Will-Do” Dimensions

Two main categories emerged when categorizing the text units relating both to a competent/incompetent lecturer and the text units relating to a benevolent/malevolent lecturer: “can-do” and “will-do” [

15]. The “can-do” described a lecturer as characterized by (1) “hard competencies” relating to the knowledge of the subject he/she was teaching; the lecturer was described as competent in terms of expertise and knowledge, the ability to explain the main topics of his/her course, of being clear, well-prepared, intelligent, and acculturated; (2) the management of classroom environment; the lecturer was described in terms of interpersonal skills relating to the involvement of students during lessons. The “will-do” grouped three aspects relating to the lecturer’s good intentions, care and concern, and personal motivation. Specifically, the “will-do” dimension consisted of: (3) benevolence; the lecturer was someone with a positive attitude, available, able to be empathetic and sociable with students, and someone with strong social skills; (4) morality; the lecturer was represented in terms of professional integrity, that is equity, reliability, and loyalty; (5) motivation; the lecturer was described as being passionate in teaching, motivated at work, and able to transmit his/her enthusiasm to students.

Whereas the same five categories emerged in the two dictionaries, that is competent/incompetent lecturer and benevolent/malevolent lecturer, the number of text units grouped into each category varied across dictionaries.

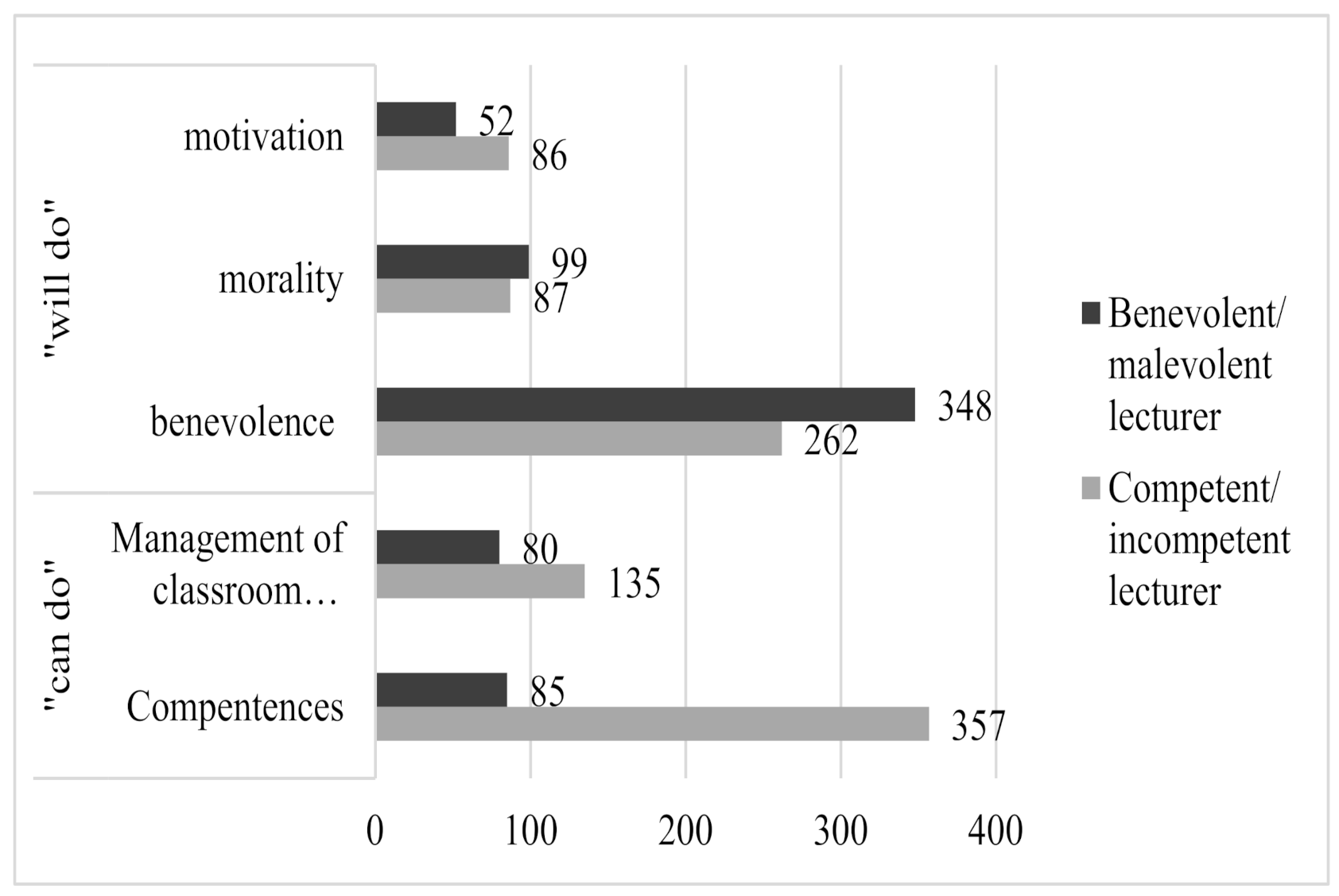

Figure 1 provides a graphic representation of the main themes pertaining to the competent/incompetent lecturer and to the benevolent/malevolent lecturer, as well as the number of text units grouped into each category and subcategory. On one hand, when asked about the competent/incompetent lecturer, participants focused mainly on the “can-do” dimensions, which are competences and management of the classroom environment. As for the competent/incompetent lecturer, the most frequent categories were competence (no. of text units = 357), belonging to the “can-do” dimension, followed by the benevolence category (no. of text units = 262), belonging to the “will-do” dimension. For instance, when asked about a competent lecturer, participant

#120 reported: “(he/she) is available for further eventual clarifications and discussion”, later coded as “benevolence”. When asked about an incompetent lecturer, participant

#123 reported that: “(he/she) is apparently a layabout”, later coded as “personal motivation.”

On the other hand, when asked about benevolent/malevolent lecturer, participants focused more on the “will-do” dimension”, that is benevolence, morality, and motivation. As for the benevolent/malevolent lecturer, the most frequent category was benevolence (no. of text units = 348), followed by morality (n. of text units = 99), both pertaining to the “will-do” dimension. Remarkable was the number of text units elicited by the benevolent/malevolent prompt word and then grouped into the “can-do” dimensions: competence (n. of text units = 85) and management of classroom environment (n. of text units = 80). For instance, when asked about a benevolent lecturer, participant #5 reported: “to have a great study material”, later coded as “competence” and “to share his/her material”, later coded as “competence”. When asked about a malevolent lecturer, participant #44 reported: “unclear (in explaining lectures)”, later coded as “competence.”

In sum, the students’ view of competent/incompetent behaviors of their hypothetical university authority was confused, with students producing words/sentences belonging both to the “can-do” dimension and to the “will-do” dimension for the same stimulus word. The same applies to the representation of the benevolent/malevolent authority. Students did not differentiate between competence and benevolence when describing their university authorities.

In the next section, we describe in depth the content of the representation of the “competent/incompetent lecturer” and then the content of the representation of the “benevolent/malevolent lecturer”.

3.2. The Competent/Incompetent Lecturer

3.2.1. The “Can-Do” Dimension

A lecturer’s competence was discussed in terms of expertise and knowledge, ability to explain the main topics of his/her course, and being clear, prepared, intelligent, and up to date. A competent lecturer had teaching experience and was pragmatic. On the contrary, an incompetent lecturer was unprepared and superficial in classes, not updated. He/she was unable to explain the subjects during lectures and did not parallel the textbooks and other lecture materials in class. As expected, this theme relating to teaching skills contained the majority of associations produced by participants when asked to describe a competent/incompetent lecturer. Examples of words/sentences for each theme and subtheme were presented in

Table 2.

However, a competent lecturer was also surprisingly described as someone who had leadership skills to manage the classroom environment. He/she was charismatic, authoritative, a go-getter, brilliant, fascinating, and charming. Participants described competence in terms of interpersonal skills relating to the involvement of students during lessons. On the contrary, students complained about an incompetent lecturer who was described as boring, distracted, rigid, insecure, and passive. Students criticized the implementation of direct lectures, with the lecturer describing the content of the slides in class and not involving the audience in any form of interaction.

3.2.2. The “Will-Do” Dimension

A lecturer’s competence was also surprisingly represented in terms of good intentions, concern, sociability, and personal motivation. Specifically, the “will-do” dimension consisted of (1) benevolence, (2) morality, and (3) personal motivation. As for benevolence, a competent lecturer was someone with a positive attitude, able to be empathetic and sociable with students. This dimension related to the social skills of faculty members. He/she was kind, respectful, and approachable. An incompetent lecturer was described as unlikable, cruel, with bad intentions and motives, and unsociable. He/she was cold, superficial, not available, and hateful. As for morality, a competent lecturer was represented in terms of professional integrity, that is, equity, reliability, and loyalty. He/she was respectful of others’ points of view, fair, objective, and not discriminatory. An incompetent lecturer was described as being impolite, unfair, and inconsistent. He/she was often late for lessons, was not doing his/her job properly, and had pet students. As for personal motivation, a competent lecturer was described as being passionate at teaching, motivated at work, and able to transmit his/her enthusiasm to students. He/she loved his/her job, loved teaching, and was fond of his/her subject. An incompetent lecturer was described as not motivated at work or not passionate at teaching. He/she was lazy, dissatisfied, lethargic, not passionate, and uninterested in what he/she was doing.

3.3. The Benevolent/Malevolent Lecturer

3.3.1. The “Will-Do” Dimension

A benevolent lecturer was described as someone with a positive attitude, able to be empathetic and sociable with students. This dimension was related to the social skills of faculty members. He/she was approachable, altruistic, empathetic, nice, indulgent, and calm. On the contrary, a malevolent lecturer was not nice, bad, unfriendly, and aggressive. He/she was not listening to students’ requests, considered the students as inferior persons, and was putting students in difficulty on purpose.

Table 3 provides some examples of words/sentences for each theme and subtheme. As for morality, the lecturer was respectful, punctual, fair, polite, and neutral. On the contrary, a malevolent lecturer was someone who was unjust and inconsistent. He/she was unfair, had preferences and was biased, not professional, vindictive, and unkind. As for personal motivations, the lecturer was described as being passionate in teaching, motivated at work, and able to transmit his/her enthusiasm to students. He/she loved his/her job, was trying to do his/her best, and was keen. On the contrary, a malevolent lecturer had no motivation at work, he/she was bored and lethargic, and had no passion for what he/she was doing.

3.3.2. The “Can-Do” Dimension

As for competence in terms of expertise and knowledge, the benevolent lecturer was also surprisingly described as being clear, prepared, intelligent, and up to date. He/she provided good examples during classes, was experienced and pragmatic. He/she gave clear indications about examinations and theses and was well-organized. On the contrary, a malevolent lecturer was someone who did not follow the teaching material, was unprepared, and was unable to explain the lesson. He/she was hasty, rude, pushover, not updated, inaccurate, and unclear. As for management of classroom environment, a benevolent lecturer was someone with good interpersonal skills and enticing. He/she was curious, captivating, resolute, and purposeful. He/she was able to involve students in the lessons and delivered light and entertaining lessons. On the contrary, a malevolent lecturer was described as cold, authoritative, boring, heavy, rigid, not creative, and inflexible (see

Table 3). The content of this category for the benevolent/malevolent prompt word was similar to the content of the same category for the competent/incompetent prompt word.

4. Discussion

In this qualitative investigation, we have explored the Italian students’ representation of two frequently described facets of trustworthiness in education contexts, namely competence and benevolence, and their possible overlap. Relatively few empirical studies have explored the trust-dimensionality in institutional contexts, such as university [

23], and few empirical investigations, e.g., [

24], have suggested the extent to which competence and benevolence judgments are interrelated and integrated. We collected qualitative data about what authorities’ competence and benevolence mean in the students’ words. As far as we know, no empirical studies have applied such a “bottom-up” approach based on qualitative data from naïve participants to study authority trustworthiness. The qualitative content analysis of Italian students’ descriptions of faculty behavior confirmed the extent to which trust components were interrelated: students listed theoretically-defined competence/incompetence characteristics as indications of both benevolence/malevolence and competence/incompetence, and theoretically-defined benevolence/malevolence characteristics as indications of both competence/incompetence and benevolence/malevolence. In line with research that has found limited consensus on trustworthiness dimensions and uncertainty related to which dimensions of trustworthiness are distinct yet related, e.g., [

7,

8], we found that the two dimensions of trustworthiness indeed overlapped in the students’ words. Furthermore, some aspects of trustworthiness emerged that were not strictly related to definitions of competence and benevolence. For instance, a category describing whether or not a lecturer had or did not have the leadership skills to manage the classroom environment also emerged. In this case, a competent/incompetent lecturer was described as being charismatic, authoritative, a go-getter, brilliant, fascinating, and charming vs. boring, distracted, rigid, insecure, and passive, whereas a benevolent/malevolent lecturer was described as someone with good interpersonal skills, enticing, and able to involve students in the lessons vs. someone who is cold, authoritative, boring, heavy, rigid, not creative, and inflexible. This aspect related to the management skills can be theoretically located in the “can-do” dimension of trustworthiness [

15]. These descriptions mirror Gabarro’s definition [

16] of interpersonal competence that described people’s abilities and skills at building social relationships that help interaction and transactions. Sometimes students also referred to the “morality” or “integrity” of a lecturer’s behavior, defined as the desire to be consistent with a set of ethics or rules. In this case, a competent/incompetent lecturer was described as being respectful of others’ points of view and professional vs. impolite, absent, or unfair, whereas a benevolent/malevolent lecturer was described as someone who is respectful, polite, and fair vs. someone who has preferences and is biased. In the literature, the concept of morality or integrity is frequently described as one important dimension of human perception, [

35,

36] and it is sometimes described as one aspect of the “will-do” component of trustworthiness [

3,

4,

15]. Some scholars proposed that benevolence is strictly distinct from integrity, but other evidence suggests these two aspects of trustworthiness are highly related especially for the relatively short-term authority relationships typical of the university context [

23]. Finally, a category describing a lecturer’s motivation to work hard and to transmit his/her enthusiasm to students was found. In this case, a competent/incompetent lecturer was described as someone who loves his/her job and teaching vs. someone who is apathetic and dissatisfied, whereas a benevolent/malevolent lecturer was described someone who is passionate vs. someone who is lethargic and bored. Other researchers found that one’s degree of passion for and attachment to his/her expertise facilitates knowledge acquisition and transfer [

37].

All these aspects were categorized into two dimensions of lecturer trustworthiness, namely “can-do” and “will-do” [

15]. In the literature, Barki and colleagues [

15] referred to these two key motivational determinants of trust as the “can-do” component of trustworthiness, whether the trustee has the skills and abilities needed to act appropriately and the ‘‘will-do’’ component, whether the trustee will choose to use those skills and abilities to act in the best interests of the trust giver. This is also in line with the two dimensions of organizational trust of Whipple and Frankel [

38]—based on Gabarro’s [

16] intra-organizational work—namely: (1) competence-based trust (i.e., specific competence and interpersonal competence) trust; (2) character-based trust (i.e., integrity, identification of motivations, consistency of behavior, and openness). In our results, these two main categories emerged when categorizing the text units related both to a competent/incompetent lecturer and the text units related to a benevolent/malevolent lecturer. In both of them, it was possible to identify competence/incompetence issues relating to the knowledge of the subject he/she was teaching and benevolence/malevolence issues.

In sum, the students’ representations of competent/incompetent behaviors of their hypothetical university authority were mixed, with students producing words/sentences belonging to the “can-do” dimension and to the “will-do” dimension for the same stimulus word. The same applied to the representation of the benevolent/malevolent authority. Students did not differentiate well between competence and benevolence when describing their university authorities. However, they gave an articulated and comprehensive representation of their university authorities, adding some aspects such as their motivation to teach and capacity to arouse the students’ curiosity. University students considered that a trustworthy university authority should be characterized by both the knowledge of subject he/she was teaching and by the lecturer’s good intentions; they appreciated aspects of good class management, morality, and motivation to teach. In line with PytlikZillig and colleagues [

23], who suggested that it may be the case that the conceptually-distinct facets of trust are statistically or practically indistinguishable, we found that competence and benevolence overlap in the students’ words. We confirm the literature’s assumptions that confusion endures about the meaning of trust and the independence of its facets [

7].

The overlap between trust-relevant concepts likely depends on the specific contexts examined. For instance, Schoorman, Mayer, and Davis [

39] noted that, whereas judgments of competence could form relatively quickly in the course of a relationship, benevolence judgments needed longer to develop. They argue that, in samples where the parties had longer-lasting relationships, multiple components of trustworthiness were more likely to be separable factors. In the Italian university context, student–lecturer relationships are short-lived, formal, and limited to a few areas of class time, exams, and student tutorials. Furthermore, our results suggest that, in an educational context, both dimensions are relevant for student–lecturer relationships. In other words, for many students, a lecturer who behaves benevolently might be, by definition, competent; and the opposite.

Overall, in educational contexts, both dimensions of competence and benevolence contribute to students’ assessment of the educational authorities’ trustworthiness [

24] and are vital for number of positive outcomes, e.g., [

11,

21,

40]. Trustworthiness is fundamental in regard to the processes required for the healthy functioning of schools and academies, and it predicts students’ engagement [

21,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41]. For instance, Mitchell and colleagues [

42] argued that if students believe that they can trust their teachers, they are more actively engaged with instructional goals and more likely to cooperate for cultivating safe schools. Analyzing qualitative data collected at a Finnish university, Kosonen and Ikonen [

43] demonstrated that, by showing trustworthiness, leaders promoted the followers’ organizational engagement. However, students’ perception about lecturers as legitimate figures of authority have been challenged in the last years [

44]. Our study results could make clearer what students mean by a trustworthy authority in order to know how to manage educational context and encourage students as to the legitimate use of authority rather than the arbitrary use of power.

One novelty of the study lies in the discovery of the importance of faculty members’ social skills when judging trustworthiness. Being able to manage a university class, involve students during a lecture, and transmit passion for the subject calls for a deep reflection on the faculty members’ educational approach to classes. It also calls for paying more attention to candidates’ social skills when recruiting and evaluating lecturers in the Italian university system.

As for the research strategy, this is a qualitative study by nature, but the data analysis strategy somehow falls in between the qualitative and quantitative approach, as the data were qualitatively content-analyzed by coding each text units into categories according to meaning. We then counted down the number of text units coded into each category, in view of the fact that the categories named most often are somehow more relevant for the participants. By linking qualitative and quantitative results, we consider that we have enriched our understanding of the issue under investigation [

45]. We have studied both the meaning of competence and benevolence in the sampled population and have also observed the distribution of the different subcategories for the benevolence and competence individually. This way, we were also able to compare the relative distribution of the text units for each subcategory across the two data corpora: the one emerging from the prompt-word “competence” and the one from the prompt-word “benevolence.” This data analysis strategy linking both qualitative and quantitative results is quite common in social psychology research [

46,

47,

48].

The study had some important limitations that ought to be kept in mind when interpreting the results. One limit is the sample composition, made up mainly of female students from central and southern Italy, and in the convenient nature of the sample, leading to low representativeness of the sample. Future research should explore the same topic in a more representative sample of students. It is necessary to emphasize that this is a preliminary study that should be extended to a larger population. However, this study adds evidencs and offers a new approach to observing the meaning of trust. Furthermore, we did not counterbalance the presentation of the stimulus words in the free-association task. Invariably, all the participants were given “competent lecturer” as the stimulus word first of all, and “benevolent (well-meaning) lecturer” afterwards. Future research should investigate the possible order effects that are of special concern in within-subject designs. Finally, future studies should take into account the role of the lecturer’s gender in the perception of trust. In Italian, nouns (such as lecturer) have gender, for instance: “il professore” for a male teacher, “la professoressa” for a female teacher. The instrument was correctly administered asking for a “competent/incompetent” or “benevolent/malevolent”—male or female—lecturer. However, in order to obtain a more homogeneous dictionary, we decided not to consider the masculine and feminine gender of nouns in the analysis. Following some notions from the stereotype content model SCM [

49], future studies could explore the perception of trust in the case of male and female lecturers.