Influence of Mothers’ Habits on Reading Skills and Emotional Intelligence of University Students: Relationships in the Social and Educational Context

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Objectives

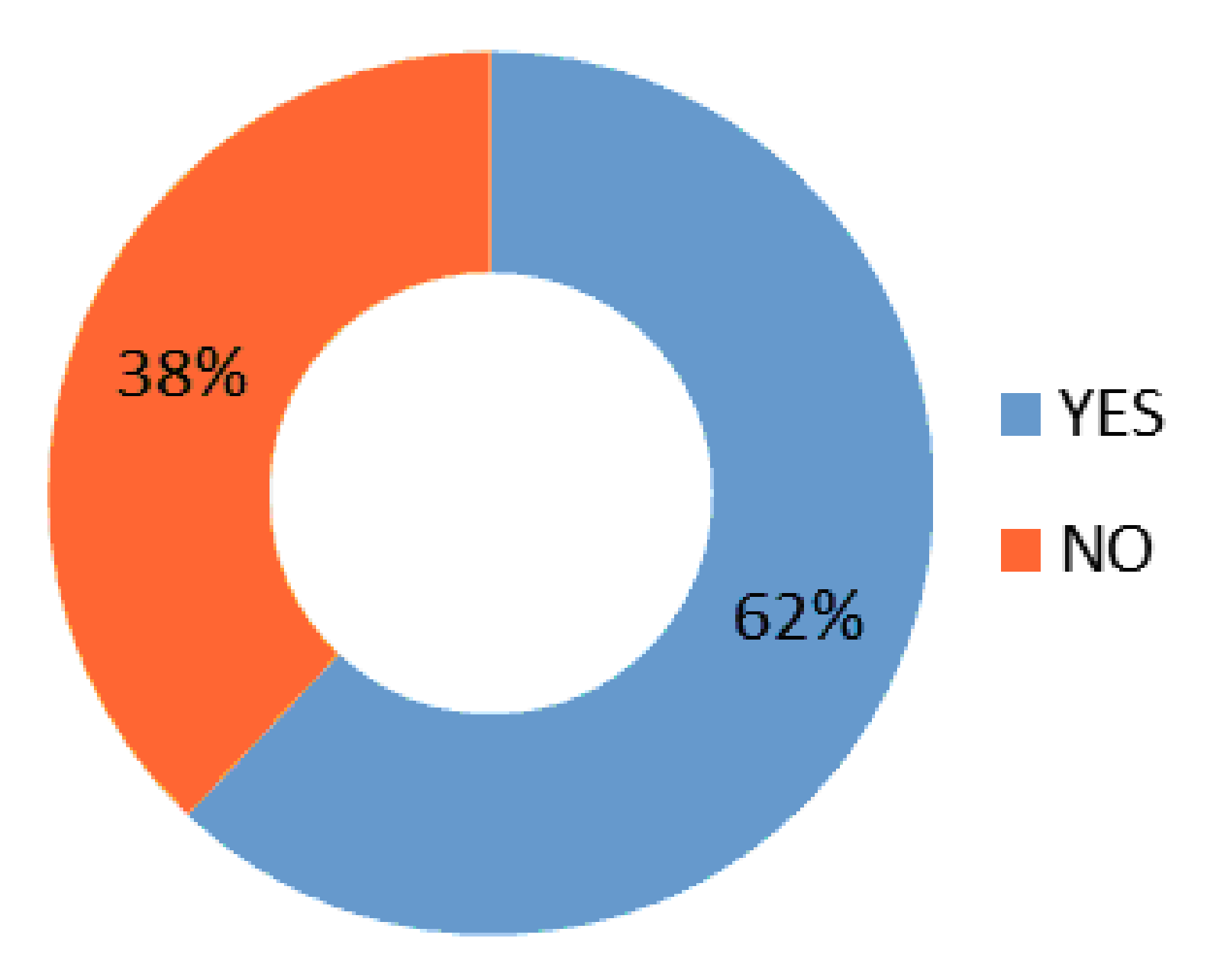

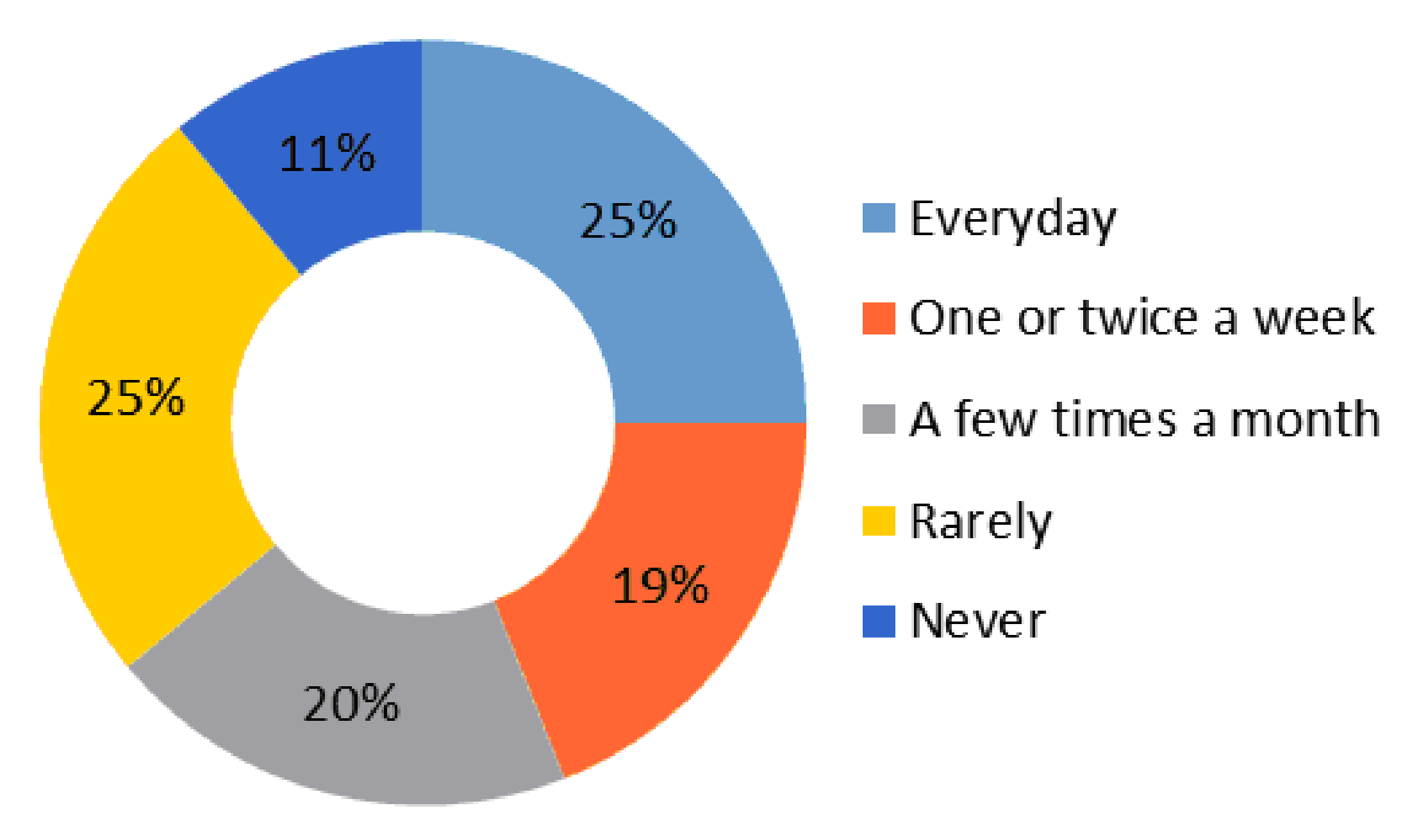

3.2. Participants and Sample

3.3. Instruments and Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Data Analysis

4.2. Moderation Analysis

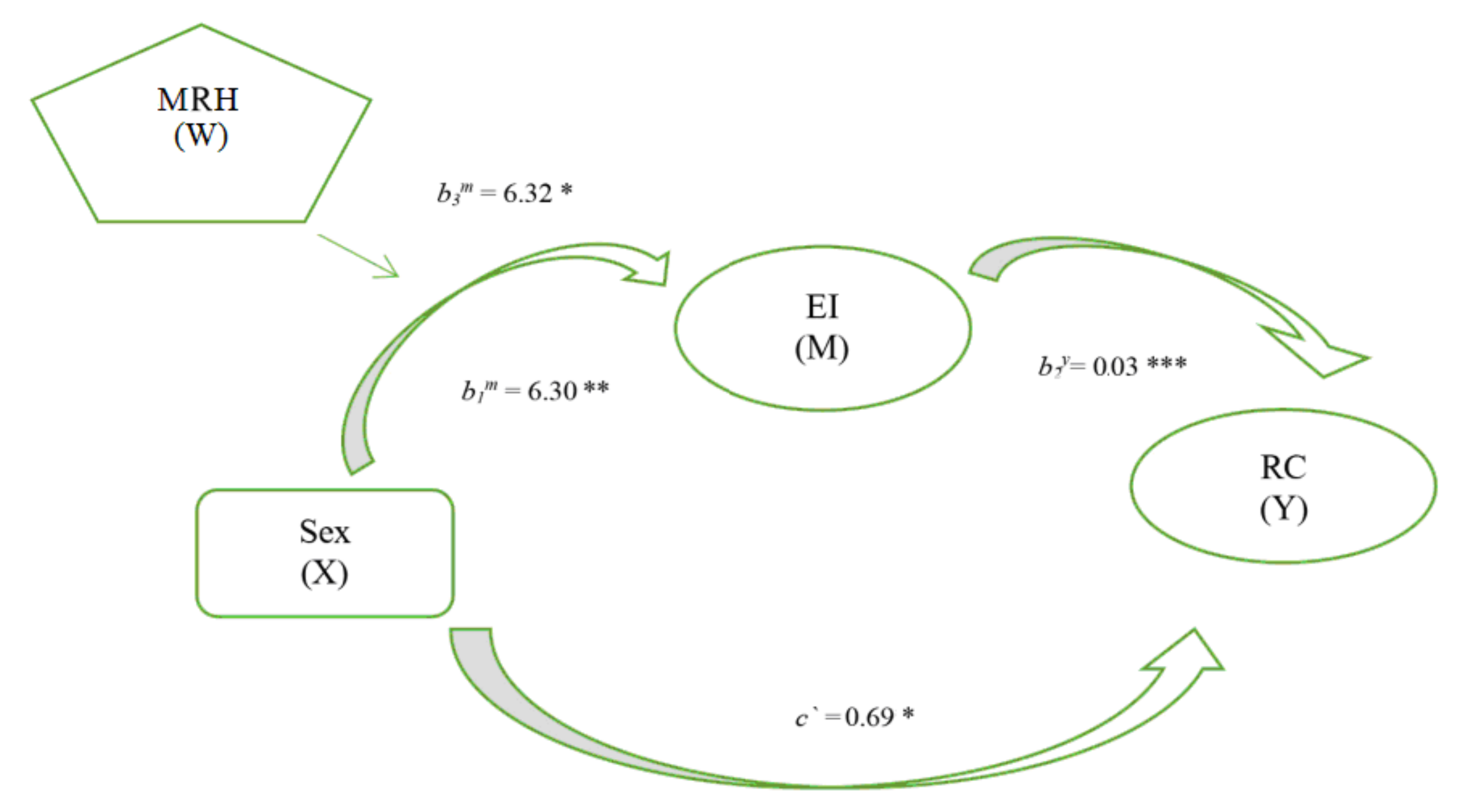

4.3. Moderated Mediation Analysis

4.4. Comparative Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rieckmann, M. Education for Sustainable Development Goals: Learning Objectives; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). PISA 2018 Reading Literacy Framework; OECD: Paris, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte. Encuesta Sobre Hábitos Lectores de la Población Escolar Entre 15 y 16 Años; Dirección General de Educación, Formación Profesional e Innovación/Educativa: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Dewitz, P.; Jones, J.; Leahy, S. Comprehension strategy instruction in core reading programs. Read. Res. Q. 2009, 44, 102–126. [Google Scholar]

- Schiefele, U.; Schaffner, E.; Moller, J.; Wigfield, A. Dimensions of Reading motivation and their relation to reading behavior and competence. Read. Res. Q. 2012, 47, 427–463. [Google Scholar]

- Grajales, G. Impacto de las TICs en los hábitos lectores de estudiantes de nivel superior. Congr. Mesoam. Educ. 2015, 2, 246–250. [Google Scholar]

- González, K.; Arango, L.; Blasco, N.; Quintana, K. Comprensión lectora, variables cognitivas y prácticas de lectura en escolares cubanos. Rev. Wimblu 2016, 11, 39–57. [Google Scholar]

- Córdoba, E.M.; Quijano, M.C.; Cadavid, N. Hábitos de lectura en padres y madres de niños con y sin retraso lector de la ciudad de Cali, Colombia. Rev. CES Psicol. 2013, 6, 53–65. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.L.; Lee, J.; Fox, J.D.; Madigan, T.P. Bringing Together Reading and Writing: An Experimental Study of Writing Intensive Reading Comprehension in Low-Performing Urban Elementary Schools. Read. Res. Quarter. 2017, 52, 311–332. [Google Scholar]

- Puc, L.; Ojeda, M.M. Promoviendo la Lectura en ámbitos ex-traescolares: Un círculo para adolescentes en Coscomatepec. Álabe 2018, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- López-Peñalver, A. Plan de Mejora: Animación a la Lectura en Familia. Master′s Thesis, Universidad de La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, D.; Berdeal, I.; Mora, E. La preparación de la familia para la atención a la promoción lectora de alumnos de segundo grado. Rev. Conrado 2018, 14, 116–124. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, D.C.; Beltrán, S.B.; Chávez, M.A. Hábitos de lectura en universitarios. Caso licenciatura de Administración de la Unidad Académica Profesional Tejupilco. Investig. Sobre Lectura 2018, 9, 73–104. [Google Scholar]

- Cordón-García, J.A. Combates por el libro: Inconclusa dialéctica del modelo digital. Prof. Inf. 2018, 27, 467–481. [Google Scholar]

- Gallego, G.; Vidal, S. La amistad, elemento clave de la comunicación y de la relación. Rev. Comun. Seeci 2017, 44, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gallego, G.; Vidal, S. El valor o la virtud en la educación. Vivat Acad. Rev. Común. 2018, 145, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldevilla, D. El papel de la prensa escrita socializador. Rev. Adcomunica 2013, 6, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Núñez, C.; Hernández, V.; Jerez, D.; Rivera, D.; Núñez, M. Las habilidades sociales en el rendimiento académico en adolescentes. Rev. Comun. Seeci 2018, 47, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, M.R. Influencias de las Metodologías, la Edad Temprana y la Participación de la Familia en el Aprendizaje Lector de los Niños y Niñas Malagueños. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Málaga, Málaga, Spain, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Parra, M.E. Análisis de las tareas para casa en educación primaria en contextos de diversidad cultural y alto índice de fracaso escolar. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lara, S.M. El valor de la lectura en el hogar. Master′s Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Zuriñe-Mengual, E. Metacomprensión e inteligencia emocional. Relación e influencia en la comprensión lectora en el alumnado de 5º y 6º de educación primaria. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gagne, F. Debating giftedness: Pronat vs. Antinat. In International Handbook on Giftedness; Shavinina, L., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 155–198. [Google Scholar]

- Sastre-Riba, S. Intervención psicoeducativa en la alta capacidad: Funcionamiento intelectual y enriquecimiento extracurricular. Rev. Neurol. 2014, 58, 59–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E. Una visión didáctica sobre la realidad de Miguel Hernández en Internet. Islas 2010, 165, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunds, K.M.; Bauserman, K.L. What teachers can learn about reading motivation through conversations with childrens. Read. Teach. 2006, 59, 414–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dueñas, J.D.; Tabernero, R.; Calvo, V. La lectura literaria ante nuevos retos: Canon y mediación en la trayectoria lectores de futuros profesores. Ocnos 2013, 11, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, M.L. Influencia de la comprensión verbal y la memoria de trabajo en la asignatura de lengua castellana en Educación Infantil. Master′s Thesis, International University of La Rioja, Logroño, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Márquez, A. Sobre lectura, hábito lector y sistema educativo. Perf. Educ. 2017, 39, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braslavsky, B. Enseñar a Entender lo Que Se Lee: La Alfabetización en la Familia y la Escuela; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Mexico City, Mexico, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E. Lectura y educación en España: Análisis longitudinal de las leyes educativas generales. Investig. Sobre Lect. 2017, 8, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakiwara-Grández, L.G. Las habilidades socioemocionales en los jóvenes: Una propuesta de desarrollo humano integral. Rev. Cienc. Comun. Inf. 2016, 21, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, V. Investigación y reflexión sobre los condicionantes del fracaso escolar. Rev. Latinoam. Estud. Educ. 2009, 39, 11–38. [Google Scholar]

- Garzón, R.; Rojas, M.; Del Riesgo, L.; Pinzón, M.; Salamanca, A. Factores que pueden influir en el rendimiento académico de estudiantes de Bioquímica que ingresan en el programa de Medicina. Rev. Educ. En Med. 2010, 13, 85–96. [Google Scholar]

- Meseguer, J. En qué se parecen los países con mejor rendimiento escolar. Rev. Antig. Alumnos Ieem 2011, 14, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E. Comprensión lectora VS Competencia lectora: Qué son y qué relación existe entre ellas. Investig. Sobre Lect. 2014, 1, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamón, M.M.; Reyes, R.L. Caracterización de la capacidad intelectual, factores sociodemográficos y académicos de estudiantes con alto y bajo desempeño en los exámenes. Av. Psicol. Latinoam. 2014, 32, 459–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, J.; Galán, A.; López-Jurado, M. Efectos de la implicación familiar en estudiantes con riesgo de dificultad lectora. Rev. Ocnos 2016, 15, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Topping, K.; Thurston, A. Peer tutoring in reading: The efects of role and organization on two dimensions of self-esteem. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 2010, 80, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F.; García-Jiménez, E. Los hábitos lectoescritores en los alumnos universitarios. Rev. Electr. Interuniv. Form. Profr. 2014, 17, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Salvador, J.A.; Agustín, M.C. Hábitos de lectura y consumo de información en estudiantes de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Zaragoza. An. Doc. 2015, 18, 2–15. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E.; Gutiérrez-Fresneda, R.; Díaz, A. Diversidad Lectora: Tipología De Textos Digitales. In Respuestas e Intervenciones Educativas en una Sociedad Diversa; Mohammed, H., Ruíz, I., Báez, D.E., Eds.; Editorial Comares: Granada, Spain, 2017; pp. 171–180. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, C. Comprensión Lectora en Español Como Segunda Lengua Para Fines Específicos. In Educación Lectora; Jiménez-Pérez, E., Ed.; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2017; pp. 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Lluch, G. Jóvenes y adolescentes hablan de lectura en la red. Ocnos Rev. Estud. Sobre Lect. 2014, 11, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Roca, A. Los fanfictions como escritura en colaboración: Modelos de lectores beta. Prof. Inf. 2019, 28, e280404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labín, A.; Taborda, A.; Brenlla, M. La relación entre el nivel educativo de la madre y el rendimiento cognitivo infanto-juvenil a partir del WISC-IV. Psicogente 2015, 18, 293–302. [Google Scholar]

- Price, J.; Kalil, A. The effect of mother–child reading time on children’s reading skills: Evidence from natural within—Family variation. Child Dev. 2019, 90, e688–e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, T.E.; Camia, C.; Facompré, C.R.; Fivush, R. A meta-analytic examination of maternal reminiscing style: Elaboration, gender, and children’s cognitive development. Psychol. Bull. 2019, 145, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, L. Mother’s education and child development: Evidence from the compulsory school reform in China. J. Comp. Econ. 2019, 47, 669–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, K.; Spilt, J.L. Understanding the origins of child-teacher dependency: Mother-child attachment security and temperamental inhibition as antecedents. Attach. Hum. Dev. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, J.S.; Córdoba, C. Rendimiento en Lectura y Género: Una Pequeña Diferencia Motivada por Factores Sociales. In Estudio Internacional de Progreso en Comprensión Lectora, Matemáticas y Ciencias Volumen II: Informe español. PIRLS-TIMSS 2011. Análisis Secundario; Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte, Instituto Nacional de Evaluación Educativa: Madrid, Spain, 2012; pp. 143–179. [Google Scholar]

- Vicente-Yagüe, M.I. Función de la Literatura Infantil y Juvenil para la Regulación de las Emociones. In Investigación e Innovación en Educación Literaria; Vicente-Yagüe, M.I., Jiménez, P.E., Eds.; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2018; pp. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Cobarro, P.H. Organizaciones emocionalmente inteligentes. Rev. Cienc. Comun. Inf. 2016, 21, 19–33. [Google Scholar]

- Blázquez, J.V.; Fernández-Andrés, M.I.; Sanz, P.; Tijeras, A.; Vélez, X.; Pastor, G. Comprensión lectora y oral: Relaciones con CI, sexo y rendimiento académico de estudiantes en educación primaria. Int. J. Dev. Educ. Psychol. Infad. Rev. Psicol. 2015, 1, 307–314. [Google Scholar]

- Páez, M.L.; Castaño, M.S. Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Psicol. Desde Caribe 2015, 32, 269–285. [Google Scholar]

- Ghabanchi, Z.; Rastegar, R. The correlation of IQ and Emotional Intelligence with the Reading Comprehension. Reading Matrix 2014, 14, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E.; Alarcón, R.; De Vicente, M.I. Intervención lectora: Correlación entre la inteligencia emocional y la competencia lectora en el alumnado en bachillerato. Rev. Psicodid. 2019, 24, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, B.; García-Hernández, M. Estudios de caso de la inteligencia emocional en los estudiantes e grado de educación. Rev. Cienc. Comun. Inf. 2018, 23, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, L. Inteligencia Emocional y Rendimiento Académico: Análisis de Variables Mediadoras. Master′s Thesis, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Vilches, I. Inteligencia emocional en la asignatura de Lenguaje y Comunicación. Contextos. Estud. Humanid. Cienc. Soc. 2004, 12, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Santamaría, A.M.; Ordoñez, E.; Gómez-Galán, J. Multiple Intelligences and ICT. In Innovation and ICTs in Education: The Diversity of the 21st-Century Classroom; Gómez-Galán, J., Ed.; River Publishers: Aalborg, Denmark, 2020; pp. 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, M.E. Reading motivation and Reading comprehension. Master′s Thesis, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J.A.; Dymnicki, A.B.; Taylor, R.D.; Weissberg, R.P.; Schellinger, K.B. The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Develop. 2011, 82, 405–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pennington, S.E. Motivation, needs support, and language arts classroom practices: Creation and validation of a measure of young adolescents’ perceptions. Rmle Online 2017, 40, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eva-Wood, A.L. Does feeling come first? How poetry can help readers broaden their understanding of metacognition. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2008, 51, 564–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, A.; Brown, M. Social Inequalities in Cognitive Scores at Age 16: The Role of Reading; Centre for Longitudinal Studies: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barrios, H.; Peña Rodríguez, L.J. Fundamental theoretical lines for an emotional education. Educ. Educ. 2019, 22, 487–509. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, P.C.; Romani, P.F. The social-emotional education and its implications on school context: A literature review. Psicol. Educ. 2019, 49, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loinaz, E.S. Teachers’ perceptions and practice of social and emotional education in Greece, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2019, 11, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Góralska, R. Emotional education discourses: Between developing competences and deepening emotional (co-) understanding. Qual. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 16, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, X. Research on the emotional education of contemporary college students. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Management, Education Technology and Economics (ICMETE 2019), Fuzhou, China, 25–26 May 2019; Atlantis Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pramanik, A.; Dhir, S. Student’s Emotion: The Power of EmotionEducation in School. In Emotion and Information Processing; Mohanty, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.S.; Hemphill, L.; Troyer, M.; Thomson, J.M.; Jones, S.M.; LaRusso, M.D.; Donovan, S. Engaging Struggling Adolescent Readers to Improve Reading Skills. Read. Res. Q. 2016, 52, 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larrañaga, E.; Yubero, S. El valor de la lectura en relación con el comportamiento lector. Un estudio sobre los hábitos lectores y el estilo de vida en niños. Rev. Ocnos 2010, 6, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, B.; Reyes, M.; Véliz, M. Memoria operativa, comprensión lectora y rendimiento académico. Lit. Lingvstica 2017, 35, 379–404. [Google Scholar]

- Bisquerra, R.; Pérez, N. Las competencias emocionales. Educ. Xxi 2007, 10, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P.; Mayer, J. What Is Emotional Intelligence. In Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence: Educational Implications; Salovey, P., Sluyter, D.J., Eds.; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1997; pp. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos-Báez, A.; Barquero-Cabrero, M.; Rodríguez-Terceño, J. La educación emocional como contenido transversal para una nueva política educativa: El caso del grado de turismo. Rev. Utopa Prax. Latinoam. 2019, 24, 147–165. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, B.G.; Bramwell, W. Promoting emergent literacy and social-emotional learning through dialogic reading. Read. Teach. 2006, 59, 554–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, A.; García-Lago, V. La lectura como factor determinante del desarrollo de la competencia emocional: Un estudio hecho con población universitaria. Rev. Investig. Educ. 2010, 28, 345–359. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, P.C. What Literature Teaches Us About Emotion; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, D.R. Transportation into a story increases empathy, prosocial behavior, and perceptual bias toward fearful expressions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2012, 52, 150–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivey, G.; Johnston, P.H. Engagement with young adult literature: Outcomes and processes. Read. Res. Q. 2013, 48, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McTigue, E.; Douglass, A.; Wright, K.L.; Hodges, T.S.; Franks, A.D. Beyond the story map: Inferential comprehension via character perspective. Read. Teach. 2015, 69, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Nero, J.R. Embracing the Other in Gothic Texts: Cultivating Understanding in the Reading Classroom. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2017, 61, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, S.; Recchia, H. Reading and the Development of Social Understanding: Implications for the Literacy Classroom. Read. Teach. 2018, 72, 569–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aram, D.; Aviram, S. Mothers’ storybook reading and kindergartners’ socioemotional and literacy development. Read. Psychol. 2009, 30, 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrián, J.E.; Clemente, R.A.; Villanueva, L.; Rieffe, C. Parent-child picture-book reading, mothers’ mental state language and children’s theory of mind. J. Child Lang. 2005, 32, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrián, J.E.; Clemente, R.A.; Villanueva, L. Mothers’ use of cognitive state verbs in picture-book reading and the development of children’s understanding of mind: A longitudinal study. Child Dev. 2007, 78, 1052–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casado, M.A.; Garmendia, M.; Garitaonandia, C. Internet y la infancia española con problemas de aprendizaje, de comportamiento y otras discapacidades. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 653–667. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Mojica, N.; Barradas, M.E. Entre risas y llanto se aprende a vivir. Vivat Acad. Rev. Comun. 2018, 145, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monzalvo, A.; Rojas, D.; Torres, N.Y. Validación de la escala de percepción de inclusión docente de la niñez migrante (PID). Rev. Comun. Salud 2018, 8, 61–70. [Google Scholar]

- Sena, W.R.; Casillas, S.; Barrientos-Báez, A.; Cabezas, M. La educomunicación en el contexto de alfabetización de personas jóvenes y adultas en América Latina: Estado de la cuestión a partir de una revisión bibliográfica sistemática. Rev. Lat. Comun. Soc. 2019, 74, 133–171. [Google Scholar]

- Llorens, A.C.; Gil, L.; Vidal, E.; Martínez, T.; Mañá, A.; Gilabert, R. Evaluación de la Competencia Lectora: La Prueba de Competencia Lectora para Educación Secundaria (CompLEC). Psicothema 2011, 23, 809–818. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.S.; Law, K.S. The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: An exploratory study. Leadersh. Q. 2002, 13, 243–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Pérez, J.C.; Repetto, E.; Extremera, N. Una comparación empírica entre cinco medidas breves de inteligencia emocional percibida. In Proceedings of the VII European Conference on Psychological Assessment, Málaga, Spain, 1 November 2004; European Association of Psychological Assessment: Málaga, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- MECD. Encuesta de Hábitos y Prácticas Culturales 2018–2019; Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Al Nima, A.; Rosenberg, P.; Archer, T.; García, D. Anxiety, Affect, Self-Esteem, and Stress: Mediation and Moderation Effects on Depression. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e73265. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, E. La inteligencia emocional como predictor del hábito lector y la competencia lectora en universitarios. Investig. Sobre Lect. 2018, 10, 30–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Salovey, P.; Vera, A.; Extremera, N.; Ramos, N. Cultural influences on the relation between perceived emotional intelligence and depression. Rips/Irsp 2005, 18, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Lizeretti, N.P.; Rodríguez, A. La inteligencia emocional en salud mental: Una revisión. Ansiedad Estras 2011, 17, 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- GeMS. The Hapiness of Reading; Universitá Roma Tre: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lamme, L.; Olmsted, P. Family Reading Habits and Children’s Progress in Reading; University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Greaney, V. Parental influences on reading. Read. Teach. 1986, 39, 813–818. [Google Scholar]

- O’Rourke, W.J. Are parents and influence on adolescent reading habits? J. Read. 1979, 22, 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini, A.D.; Brody, G.H.; Sigel, I.E. Parents’ book-reading habits with their children. J. Educ. Psychol. 1985, 77, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, S.; Tan, V. Understanding the reading habits of children in Singapore. J. Educ. Media Libr. Sci. 2007, 45, 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Yusof, N.M. Influence of family factors on reading habits and interest among level 2 pupils in national primary schools in Malaysia. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010, 5, 1160–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wollscheid, S. Parents’ cultural resources, gender and young people’s reading habits--findings from a secondary analysis with time-survey data in two-parent families. Int. J. About Parents Educ. 2013, 7, 69–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mansor, A.N.; Rasul, M.S.; Abd Rauf, R.A.; Koh, B.L. Developing and sustaining reading habit among teenagers. Asia-Pac. Educ. Res. 2013, 22, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, J.; Jabeen, Z.; Qutoshi, S.B. Perceptions of teachers about the role of parents in developing reading habits of children to improve their academic performance in schools. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 2018, 5, 42–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, Z. Parent’s role in promoting reading habits among children: An empirical examination. Libr. Philos. Pract. Electron. J. Univ. Neb. 2020, 3958. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/3958/ (accessed on 5 September 2020).

- Mancini, A.L.; Monfardini, C.; Pasqua, S. Is a good example the best sermon? Children’s imitation of parental reading. Rev. Econ. Househ. 2017, 15, 965–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, A.G.; Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Mother-child interactions, attachment, and emergent literacy: A cross-sectional study. Child Dev. 1988, 59, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bus, A.G.; Belsky, J.; van Ijzendoom, M.H.; Crnic, K. Attachment and bookreading patterns: A study of mothers, fathers, and their toddlers. Early Child. Res. Q. 1997, 12, 81–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigel, D.J.; Martin, S.S.; Bennett, K.K. Mothers’ literacy beliefs: Connections with the home literacy environment and pre-school children’s literacy development. J. Early Child. Lit. 2006, 6, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Galán, J. Internet y la Palabra: Un Nuevo Paradigma Comunicativo en la Cultura y la Educación Del Siglo XXI. In El Patrimonio Cultural: Tradiciones, Educación y Turismo; Martos, E., Martos, A., Eds.; Instituto Cultural El Brocense: Cáceres, Spain, 2009; pp. 171–183. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, S. The impact of e-books on young children’s reading habits. Publ. Res. Quart. 2010, 26, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucirkova, N.; Littleton, K. The Digital Reading Habits of Children. A National Survey of Parents’ Perceptions of and Practices in Relation to Children’s Reading for Pleasure with Print and Digital Books; The Open University and Book Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunrombi, S.A.; Adio, G. Factors affecting the reading habits of secondary school students. Libr. Rev. 1995, 44, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKool, S.S. Factors that influence the decision to read: An investigation of fifth grade students’ out-of-school reading habits. Read. Improv. 2007, 44, 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes-Hassell, S.; Rodge, P. The leisure reading habits of urban adolescents. J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2007, 51, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoester, M. Inquiry into urban adolescent independent reading habits: Can Gee’s theory of Discourses provide insight? J. Adolesc. Adult Lit. 2009, 52, 676–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, B. A Study on the Factors Affecting Reading and Reading Habits of Preschool Children. Int. J. Engl. Linguist. 2020, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granado, C. Teachers as readers: A study of the reading habits of future teachers. Cult. Educ. 2014, 26, 44–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salguero, J.; Fernández-Berrocal, P.; Ruíz, D.; Castillo, R.; Palomera, R. Inteligencia Emocional y ajuste psicosocial en la adolescencia: El papel de la percepción emocional. Eur. J. Educ. Psychol. 2011, 4, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Vilar, M.; Serrano-Pastor, L.; Sala, F.G. Emotional, cultural and cognitive variables of prosocial behaviour. Curr. Psychol. 2019, 38, 912–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiana, A. Nuevos desafíos para la educación y la formación en España y en la Unión Europea. Cee Particip. Educ. 2009, 10, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Luzón, A.; Sevilla, D.; Torres, M. El proceso de Bolonia: Significado, objetivos y controversias. Av. Supervison Educ. 2009, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Sayans, P.; Vázquez-Cano, E.; Bernal, C. Influencia de la riqueza familiar en el rendimiento lector del alumnado en PISA Influence of family wealth on student reading performance in PISA. Rev. Educ. 2018, 380, 129–155. [Google Scholar]

- Jerrim, J.; Moss, G. The link between fiction and teenagers’ reading skills: International evidence from the OECD PISA study. Br. Educ. Res. J. 2019, 45, 181–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Cano, E.; Gómez-Galán, J.; Infante, A.; López-Meneses, E. Incidence of a non-sustainability use of technology on students’ reading performance in Pisa. Sustainability 2020, 12, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E.; Alarcón, R.; De Vicente-Yagüe, M.I. Correlation study of emotional intelligence and reading competence in high school. Rev. Psicodid. 2019, 24, 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Pérez, E.; Martínez-León, N.; Cuadros-Muñoz, R. La influencia materna en la inteligencia emocional y la competencia lectora de sus hijos. Ocnos 2020, 20, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabia, B. Gender and emotional intelligence as predictors of tourism faculty students’ career adaptability. Adv. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2018, 6, 188–204. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiménez-Pérez, E.; Barrientos-Báez, A.; Caldevilla-Domínguez, D.; Gómez-Galán, J. Influence of Mothers’ Habits on Reading Skills and Emotional Intelligence of University Students: Relationships in the Social and Educational Context. Behav. Sci. 2020, 10, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120187

Jiménez-Pérez E, Barrientos-Báez A, Caldevilla-Domínguez D, Gómez-Galán J. Influence of Mothers’ Habits on Reading Skills and Emotional Intelligence of University Students: Relationships in the Social and Educational Context. Behavioral Sciences. 2020; 10(12):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120187

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiménez-Pérez, Elena, Almudena Barrientos-Báez, David Caldevilla-Domínguez, and José Gómez-Galán. 2020. "Influence of Mothers’ Habits on Reading Skills and Emotional Intelligence of University Students: Relationships in the Social and Educational Context" Behavioral Sciences 10, no. 12: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120187

APA StyleJiménez-Pérez, E., Barrientos-Báez, A., Caldevilla-Domínguez, D., & Gómez-Galán, J. (2020). Influence of Mothers’ Habits on Reading Skills and Emotional Intelligence of University Students: Relationships in the Social and Educational Context. Behavioral Sciences, 10(12), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs10120187