Abstract

The double burden of malnutrition (DBM) and anaemia is a growing concern in developing countries. Using the cross-sectional Bangladesh Demographic Health Survey, 2011, 5763 mother–child pairs were examined. In households where the mother was overweight, 24.5% of children were stunted, 19.8% underweight, 9.3% wasted, and 51.7% anaemic. Significant regional differences were found in DBM and anaemia as well as drinking water source, while DBM alone was more common in more well-off households (based on wealth index) and where the father was employed in skilled or service occupations. More policy and awareness programmes are needed to address the coexistence of child undernutrition and maternal overweight/obesity and anaemia in the same household.

1. Introduction

The number of undernourished people in the world increased from 777 million to an estimated 815 million in 2016. At the same time, adult obesity continues to rise in all regions. Multiple forms of malnutrition therefore co-exist, with countries experiencing simultaneously high rates of child undernutrition and adult obesity [1]. Maternal and child double burden (MCDB) can be defined as an overweight mother paired with an undernourished child. Nutrition disparities are more evident in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with higher prevalence of undernutrition, overweight or obesity (overnutrition), or both [2,3]. The social determinants of health (SDoH) have been consistently associated with both undernutrition in children and overweight in mothers [4,5,6]. The overall anaemia prevalence among children less than 5 years old is 54.2% in 52 low, lower-middle, and upper-middle countries according to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, collected between 2005 and 2016 [7].

In Bangladesh (Figure 1), the prevalence of child undernutrition decreased from 51% to 36% between 2004 and 2007 due to economic growth. On the other hand, maternal overweight increased from 9% to 24% over the same time period [8]. The association between socio-demographic factors and the double burden of malnutrition (DBM) has been examined in several studies [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19] around the world. In Guatemala, stunted child and overweight mother (SCOM) was more prevalent among poor and middle socioeconomic status groups as compared to the rich households [9]. In Latin America, Mexico, Brazil, Columbia, and Africa, poor maternal education and low socioeconomic status were associated with DBM [10,11,12,13]. On the other hand, studies in China, Indonesia, Vietnam, India, and Bangladesh showed that DBM is more prevalent among high-income households compared to low-income households [14,15,16,17,18]. Jehn et al. used Demographic and Health Survey datasets from 18 lower- and middle-income countries and found that lower level of maternal education, number of siblings, and relative household poverty were associated with DBM [19]. In Bangladesh, only a few small-scale community-based studies have been undertaken with regard to DBM, and no nationwide studies have been undertaken [20].

Figure 1.

A map of Bangladesh showing seven administrative divisions [21].

The present study uses a nationally representative sample from Bangladesh to examine the coexistence of overweight mothers with undernourished (stunted, underweight, and wasted) and anaemic children living in the same household. The study also examines the differences in DBM and anaemia in relation to a number of socio-economic variables. This study provides important information on the reality of the health of the mother and the child in a developing country such as Bangladesh.

2. Materials and Methods

The data source for this research was the Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey (BDHS), 2011. The DHS programmes are nationally representative, cross-sectional household surveys. They provide a wide range of information mainly related to population, health, and nutrition. The sample design used in DHS surveys is mainly based on a two-stage cluster format. In the first stage, enumeration areas (EAs) are generally drawn up from census information. Secondly, a sample household is drawn from each selected EA. Demographic and Health Survey data are representative at the national level, residence level, and regional level [9].

BDHS 2011 obtained informed consent from the participants before the survey. The contents of the household and individual questionnaires were based on the Monitoring and Evaluation to Assess and Use Results (MEASURE) DHS model questionnaires. Ethical permission was obtained by the Macro International Inc. Institutional Review Board on 22 February 2011 when the DHS were carried out, with ICF Macro Project Number: 631561.0.000.00.091.01. All data in the present study were anonymous and no additional ethical permission was required. BDHS used five types of questionnaires: a Household Questionnaire, a Woman’s Questionnaire, a Man’s Questionnaire, a Community Questionnaire, and two Verbal Autopsy Questionnaires to collect data on causes of death among children under age 5. These model questionnaires were adapted for the use in Bangladesh during a series of meetings with a Technical Working Group (TWG) that consisted of representatives from National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT); Mitra and Associates; International Centre for Diarrheal Diseases and Control, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B); United States Agency for International Development (USAID)/Bangladesh; and MEASURE DHS. Draft questionnaires were then circulated to other interested groups and were reviewed by the 2011 BDHS Technical Review Committee [9]. Fieldwork for the 2011 BDHS was carried out by 16 interviewing teams, each consisting of one supervisor, one field editor, five female interviewers, two male interviewers, and one logistics staff member. Data collection was implemented in five phases, starting on 8 July 2011 and ending on 27 December 2011. In addition, during 2–19 January 2012 there were re-visits to collect blood samples from respondents interviewed during Ramadan who had agreed to participate in blood testing but declined to be tested during Ramadan. Fieldwork was also monitored through visits by representatives from USAID, Inner City Fund (ICF) International, and NIPORT [9].

A total of 18,222 ever-married women aged 12–49 were identified in these households, and 17,842 were interviewed, yielding a response rate of 98 percent. In one-third of the households, ever-married men over age 15 were eligible for interview. Because there were only 90 ever-married women aged 12–14 (less than one percent), these women were excluded. Children aged from 0 to 59 months were selected. Only the first child of each family was selected. Only children and their mothers having anthropometric information (height and weight) and all the socio-economic variables were included. Finally, 5783 mother–child pairs were selected based on the abovementioned criteria. The principal reason for nonresponse among women and men was their absence from home despite repeated visits to the household. The response rates do not vary notably by urban–rural residence.

Following WHO recommendations, any children with height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) and weight-for-age Z-score (WAZ) either above +6 or below −6 and Weight for Height Z-score WHZ above +5 or below −5 were excluded. For women, anthropometric measurements above and below 4 standard deviation (SD) were considered outliers and were excluded from the data [22]. Children and women lacking information for any of the socio-economic variables of the study were also excluded. In total, 5763 mother–child pairs with complete information were analysed. The total number of mother–child pairs having haemoglobin data was 1661. The smaller sample size for haemoglobin concentration data was because BDHS chose to only take a sample of blood from every third household. No significant differences were found between mother–child pairs with complete or incomplete information.

The nutritional status was assessed using anthropometry (body mass index (BMI) in mothers and stunting, underweight, and wasting in children) and anaemia status of mother–child pairs. Height and weight were measured using standard procedures by trained staff. Children younger than 2 years were measured lying down (recumbent length) on an anthropometric board, while standing height was measured for older children and mothers. For weighing of children and mothers, a weighing scale was used which allows for weighing of very young children through an automated mother–child adjustment that eliminated the mother’s weight while she was standing on the scale with her baby. Haemoglobin concentration was determined using a Hemocue (Radiometer Medical ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark), a portable photometer which uses the absorption of light from a single drop of blood to measure haemoglobin concentration. Maternal BMI was categorised into three categories of underweight (BMI < 18.5), normal (18.5 to 24.9), and overweight (≥25.0) and stunting, underweight, and wasting by z-scores of <−2.00 of height-for-age, weight-for-age, and weight-for-height, respectively, following the WHO guidelines [22]. All mother–child combinations, e.g., of BMI and stunted and not stunted children, were included in the analyses, but only data on overweight mothers with undernourished children are presented in the results.

χ2 testing and sequential multinomial regression analysis was performed to examine the association between maternal and child nutritional status and the socio-economic variables. Initially the analyses removed the linear and quadratic effects of age and sex before testing for the significance of a socio-economic variable. Later, after removing the linear and quadratic effects of age and sex, all the socio-economic variables were entered into the model except for the variable of interest. In χ2 test, Cramer’s V was used to observe the effect size. In the analyses, one category with a socio-economic variable has to be the reference value, and Region Sylhet was chosen (arbitrarily). IBM SPSS 21 (IBM, New York, USA) software was used in data analysis, and the cut-off for significance was p < 0.05.

3. Results

The occurrence of maternal overnutrition and child undernutrition in the same household was observed in the current study. Of the total sample of overweight mothers, 24.5% had stunted children, 19.8% underweight children, 9.3% wasted children, and 51.7% anaemic children. However, there was significant heterogeneity in the occurrence of the DBM, as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1.

Prevalence of overweight mother and stunted child pairs through the socio-demographic variables.

3.1. Overweight Mothers and Stunted Children

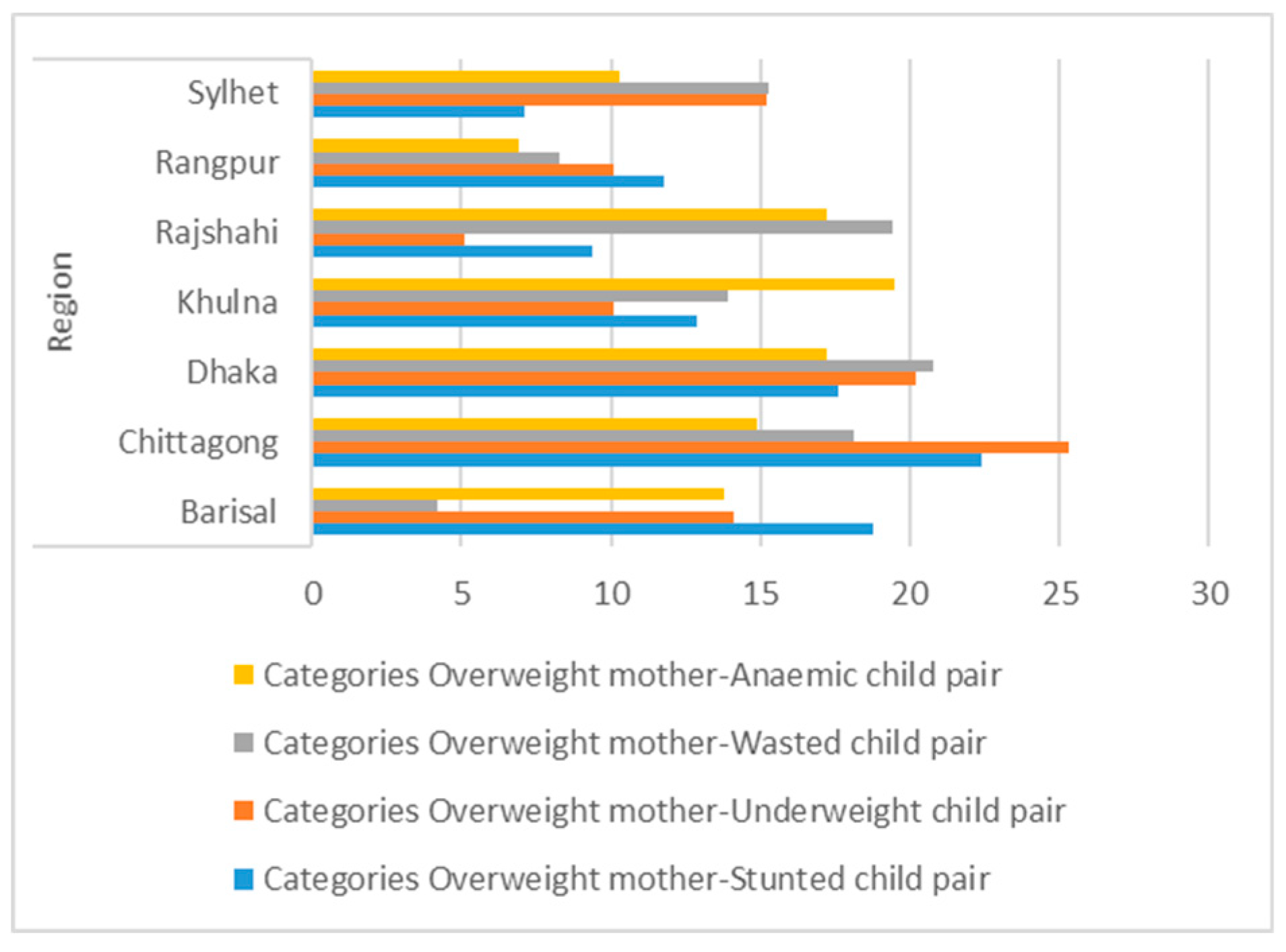

For overweight and stunting there was marked regional variation (Figure 2) with the highest prevalence in Chittagong (22.4%) and the lowest in Sylhet (7.1%). Rural areas had a higher prevalence (58.8%) while fathers/husbands working in service had a much higher prevalence (44.7%) than other occupations. There was an association with education, and fathers/mothers with primary and secondary education levels had the highest prevalence (>30%).

Figure 2.

Regional distribution of double burden of malnutrition (DBM).

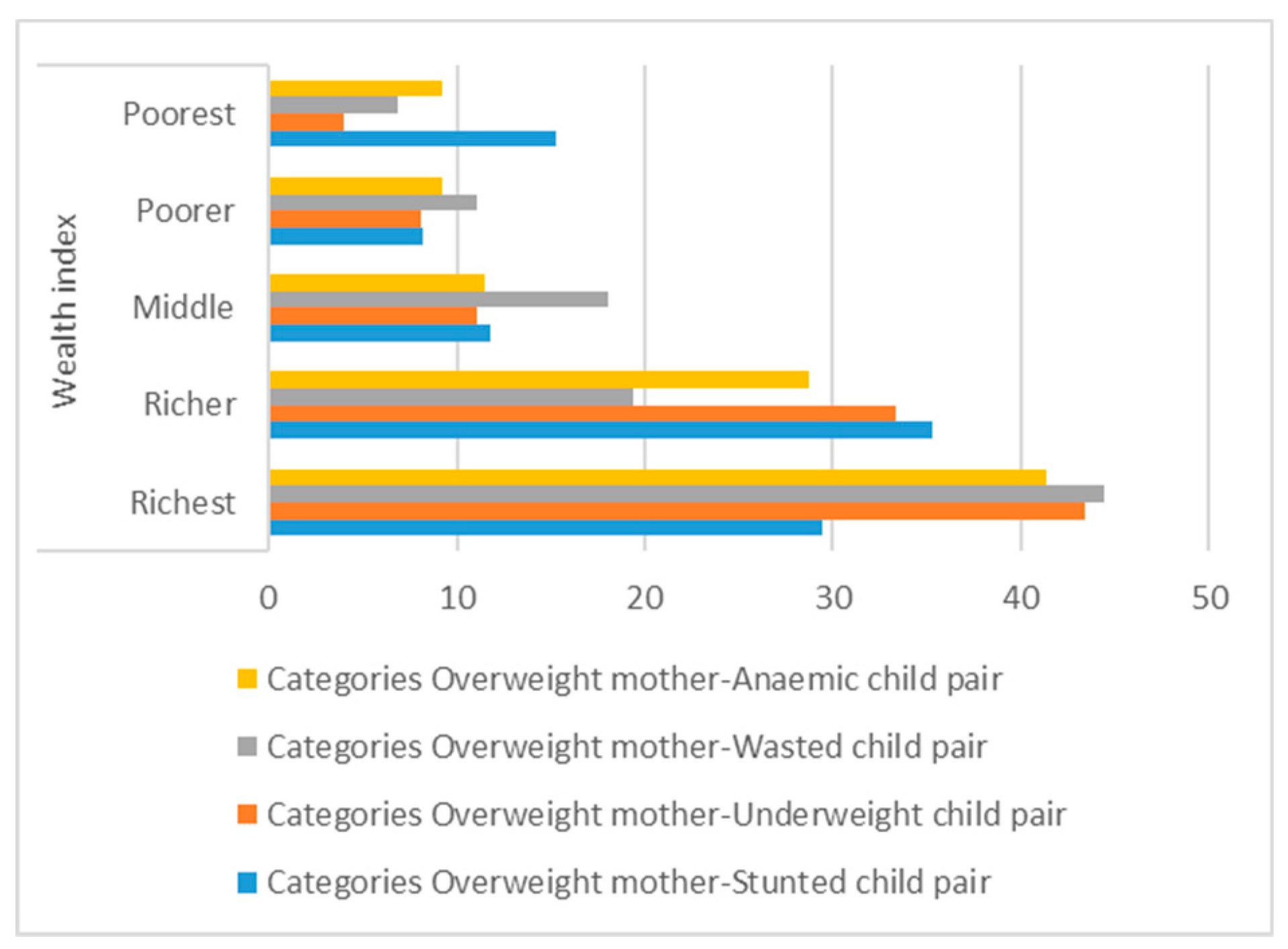

Households with three possession scores had the highest prevalence (32.9%) as did “richer” households on the wealth index (35.3%) (Figure 3). Households using flush toilets, tube-well water, coal/wood as cooking fuel, and with more than five family members all had higher prevalence.

Figure 3.

Distribution of DBM across the wealth index.

After sequential multinomial logistic regression, only region, father’s occupation, and wealth index remained significant (p < 0.05) Barisal was the region with the highest prevalence after taking into account the other socio-economic variables, while children from richer families on the wealth index had the highest prevalence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of overweight mother and stunted child pairs by socio-demographic variables.

3.2. Overweight Mothers and Underweight Children

Chittagong had 25% overweight mothers with underweight children. More than half of the overweight mothers with underweight children were found in urban areas. Parental occupation followed a similar trend to the overweight mothers with stunted children. The occurrence of overweight mothers with underweight children increased with improvement of the father’s/husband’s educational status. Overweight mothers with underweight children were more often observed in parents having secondary-level education. The percentages of overweight mothers with underweight children were high in richer families with improved toilet facilities (Table 3). After sequential multinomial logistic regression, only region, father’s occupation, and wealth index remained significant (p < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Prevalence of overweight mothers and underweight children through socio-demographic variables.

Table 4.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of overweight mother and underweight child pairs by socio-demographic variables.

3.3. Overweight Mothers and Wasted Children

Dhaka had more overweight mothers with wasted children among the seven regions. Urban areas had more overweight mothers with wasted children than rural areas. Parental occupation and type of housing showed a similar trend as those for overweight mothers with stunted/underweight children. The number of overweight mothers with wasted children increased with improvements in parental education, wealth index, possession score, and toilet facilities (Table 5). After sequential multinomial logistic regression, only region and father’s occupation remained significant (p < 0.05) (Table 6). The results showed a similar pattern when using the Asian cut-off for BMI to define maternal overweight. In a multinomial regression analysis, father’s/husband’s occupation and wealth index were significantly associated with double burden of malnutrition in mother–child pairs (Appendix A Table A1).

Table 5.

Prevalence of overweight mother and wasted child pairs through the socio-demographic variables.

Table 6.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of overweight mother and wasted child pairs by socio-demographic variables.

3.4. Overweight Mothers and Anaemic Children

Khulna had almost 20% overweight mothers with anaemic children, which was highest among the seven regions. Rural households had a high number of overweight mothers with anaemic children. Fathers working in services had a high number of overweight mothers with anaemic children. More than 80% of the unemployed mothers were overweight with anaemic children.

The number of overweight mothers with anaemic children increased with improvements in father’s education, wealth index, and toilet facilities, and vice versa (Table 7). The results showed a similar pattern when using the Asian cut-off for BMI to define maternal overweight (Appendix A Table A1). In a multinomial regression analysis, region and drinking water were significantly associated with double burden of malnutrition in mother–child pairs. Households having a piped drinking water source were 70% less likely to have underweight mothers with anaemic children (Table 8).

Table 7.

Prevalence of overweight mother and anaemic child pairs by socio-demographic variables.

Table 8.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of overweight mother and anaemic child pairs by socio-demographic variables.

4. Discussion

The present paper observed the existence of a double burden of malnutrition in the same household. Overweight mothers with undernourished (stunted/underweight/wasted) children were found under the same roof. When the effects of all other variables were removed, the double burden of malnutrition was significantly associated with region, wealth index, and father’s/husband’s occupation. Overweight mothers and undernourished children were more evident in the richest households (Figure 3). The prevalence of malnourished mother and anaemic children improved with an improvement of drinking water quality. Overweight mothers with anaemic children were 27% more likely to use piped water as the source of their drinking water.

Oddo et al. [18] observed the existence of stunted children and overweight mothers within the same household in Bangladesh. They used data from the Bangladesh Nutritional Surveillance Project (BNSP) (2003–2006) and reported that double-burden households were more likely to be among the wealthier quintiles, which is consistent with the current study result. Other researchers also found similar results [13,23,24]. Although research is limited, an increased prevalence of MCDB has been observed in countries that are in the midst of their nutrition transition [25,26].

In a regional context, Shukla et al. [27] have confirmed the co-existence of under-and overnutrition in South Asian countries. Demographic and socioeconomic transitions have been occurring for the last few decades in this region [28]. Using data collected by Helen Keller International (HKI), Shafique et al. [29] observed an increasing trend of overweight mothers among urban poor women, but it was not widely evident in rural poor women. In the present study, 54% urban and 46.2% rural women were overweight. There are extensive differentials hidden behind these simple urban/rural comparisons. Different socioeconomic groups living in slums within the same urban areas are also exposed to the greatest health risks. The stunting rates among poor urban children are as high as those among poor rural children.

In the present paper, three major big cities (Dhaka, Chittagong, and Khulna) had the highest percentages of overweight mothers with undernourished children (Figure 2). More than 20% of mothers who were overweight had children suffering from either stunting, underweight, or wasting. More than half of the urban households had stunted children with overweight mothers (SCOWT). SCOWT is not entirely an urban phenomenon because the prevalence of SCOWT is affected by both the rates of childhood stunting (high in rural areas) and maternal overweight (high in urban areas) [11].

With increased female employment and related time constraints, urban dwellers also increase their consumption of street foods or processed, ready-to-eat foods. Street foods often contain unhealthy levels of energy, saturated fats, salt, and refined sugars. They are also a good source of microbes responsible for food-borne illnesses due to poor hygiene status [30,31,32]. As a consequence, urban mother–child pairs are prone to both overweight and underweight.

There is a general perception that women living in urban areas are more likely to engage in income-generating activities outside the home than rural women. Previous analysis of the Demographic and Health Surveys in developing countries showed that the main difference between urban and rural areas was not the rate of women’s employment (which was roughly 50% in both areas) but rather the fact that urban mothers were much less likely to take their child to their place of work than rural women [33]. This is likely due to the types of work women engage in: agriculture in rural areas and factory, market, or street work in urban areas, which may be either unsafe or unsuitable for bringing the child along. Given these circumstances, the net impact of urban women’s engagement in paid work on child well-being will depend on the quality of the substitute child care they are able to secure. Little information is available on the type and quality of childcare used by working women and this issue thus remains poorly understood. Evidence suggests, however, that women’s employment and child care decisions are highly influenced by the age of their youngest child [34].

Mothers educated up to primary-level education from poor households with unimproved toilet facility were underweight with anaemic children. Lower rates of extra-household employment and reduced economic power within the household [35,36], higher rates of infection related to poor sanitation or high rates of reproductive tract infections, gynaecological morbidity, or sexually transmitted diseases [37,38] could be the possible causes of mother–child undernutrition. Overweight mothers with anaemic children tended to be from households having at least a possession score of 3 with improved toilet facilities (Table 1). In the South Asian cultural context, the dimensions of autonomy such as freedom of movement, decision-making power, and control over finances can also influence service use and service choice. This may lead to inappropriate treatment of illnesses.

Nutrition transition is caused by globalisation, rapid urbanisation, and economic development. A major shift in food consumption and physical activity patterns is evident in nutrition transition [39]. Urban populations are gradually shifting towards diets containing excessive amounts of energy, saturated fats, refined sugars, and salt, replacing a staple cereal-based diet [39]. Besides that, a sedentary lifestyle in the urban population is increasing the risk of obesity and chronic non-communicable diseases such as coronary heart diseases, diabetes, and cancer.

In recent years, adult overnutrition has come to exist simultaneously with child undernutrition in Bangladesh, which is well known as the double burden of malnutrition. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) have confirmed the double burden of malnutrition, i.e., the co-existence of under- and overnutrition, in South Asia. For the last few decades, this region has been undergoing demographic and socioeconomic transitions [40]. These transitions include a shift in nutrition and morbidity patterns, and Bangladesh is gradually paving its way to the double burden of malnutrition. Hence, along with measuring the prevalence of undernutrition, it is obviously important to determine the national prevalence of overweight as well as its determining factors [41].

According to the foetal origin of disease, early (intrauterine or early post-natal) undernutrition causes an irreversible differentiation of metabolic systems. For example, a foetus of an undernourished mother will respond to a reduced energy supply by switching on genes that optimise energy conservation. This survival strategy causes a permanent differentiation of regulatory systems that result in an excess accumulation of energy (and, consequently, of body fat) when the adult is exposed to an unrestricted dietary energy supply. Consequently, an undernourished child grows into an obese adult given the proper environment. Based on our current findings and the limited evidence available to date, it is likely that maternal obesity plays an important role in child anaemia. Kelven et al. observed that the larger size of foetuses of obese mothers may negatively influence cord blood iron markers [42]. Even after adjusting for infant size at birth, maternal obesity and excessive gestational weight gain were negatively associated with neonatal iron status. However, the mechanisms underlying this association are still unclear [43,44,45].

Increasing economic status and gross domestic product (GDP) decrease undernutrition but the relationship between GDP and nutrition is complex. Being poor in a middle-income country increases the risk of obesity compared with being rich in the same country [37]. In urbanised developing countries, the availability of cheap, energy-dense foods could be the hidden cause of obesity. Besides that, undernutrition in children (aged under five years) tends to increase in urban areas of countries in socio-economic transition [39]. Caballero [44] defined this phenomenon as the “underweight–overweight paradox”. Effectively, the underweight–overweight paradox poses a challenge to public health programs, since most programmes are designed to reduce undernutrition. Large-scale nutrition-sensitive programmes which address the key underlying determinants of nutrition are necessary to enhance the coverage and effectiveness of nutrition-specific interventions [45].

5. Conclusions

The increasing number of overweight mothers is becoming a new health concern for Bangladesh. The results of this recent study clearly show that double burden exists in Bangladesh and in the same household. Apart from that, the co-existence of overweight mother and undernourished children in the same household portrays the complex dynamics of possible causes. Future longitudinal studies are needed to understand the factors linked to DBM risk. The interaction between maternal overweight/obesity and early childhood undernutrition can be identified and addressed by effective large-scale population studies to reduce the long-term risk of obesity in the offspring.

6. Limitations

The Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey is based on a cross-sectional study design. Although the data collection and study design were of high quality, the data did not allow us to draw causal relationships between variables in the current study. The data lacked information on maternal energy intake, physical activity level, and micronutrient intake, which are important for a proper assessment of nutritional status. Only one in every three households was selected for haemoglobin concentration assessment, which may not give a clear idea about the anaemia status of the whole population. It was not possible to examine the relationship between child feeding practise and infection and nutritional status due to a large amount of missing information on complementary feeding, immunisation, and infectious disease. Incomplete information and inconsistent information on some selected variables complicated the analysis process considerably.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; methodology, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; software, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; validation, C.G.N.M.-T.; formal analysis, S.M.; investigation, S.M.; resources, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; data curation, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M.; writing—review and editing, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; visualization, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; supervision, C.G.N.M.-T.; project administration, S.M. and C.G.N.M.-T.; funding acquisition, S.M.

Funding

This research was supported through the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (CSC), UK.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the support I have received for my research through the provision of The National Institute of Population Research and Training NIPORT, Bangladesh and MEASURE DHS for allowing us to use BDHSs 2011 data for our analysis. The funder had no role in the design, analysis or writing of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of DBM in mother–child pairs by socio-demographic variables for the Asian cut-off point (maternal BMI).

Table A1.

Sequential multinomial logistic regression analysis of DBM in mother–child pairs by socio-demographic variables for the Asian cut-off point (maternal BMI).

| DBM | Variables | Categories | OR | CI | χ2 | p-Value | R2 | Effect Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overweight mother with stunted child | Region | Barisal | 1.6 | 1.25–1.95 | 54.5 | 0.004 | 0.3 | Small |

| Chittagong | 1.15 | 1.05–1.25 | ||||||

| Dhaka | 1.19 | 1.06–1.31 | ||||||

| Khulna | 0.87 | 0.77–0.97 | ||||||

| Rajshahi | 0.68 | 0.40–0.97 | ||||||

| Rangpur | 1.39 | 1.15–1.63 | ||||||

| Sylhet | 1 | - | ||||||

| Father’s occupation | Service | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 41.1 | 0.004 | 0.3 | Small | |

| Skilled manual | 0.7 | 0.57–0.83 | ||||||

| Unskilled labour | 0.61 | 0.24–0.97 | ||||||

| Agricultural work | 0.7 | 0.44–0.96 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1 | - | ||||||

| Wealth index | Richest | 0.67 | 0.46–0.88 | 54.1 | <0.001 | 0.3 | Small | |

| Richer | 1.13 | 1.11–1.19 | ||||||

| Middle | 0.64 | 0.41–0.87 | ||||||

| Poorer | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | ||||||

| Poorest | 1 | - | ||||||

| Overweight mother with underweight child | Region | Barisal | 0.92 | 0.88–0.96 | 64.2 | <0.001 | 0.3 | Small |

| Chittagong | 0.87 | 0.86–0.88 | ||||||

| Dhaka | 0.73 | 0.56–0.90 | ||||||

| Khulna | 0.45 | 0.03–0.87 | ||||||

| Rajshahi | 0.61 | 0.35–0.87 | ||||||

| Rangpur | 0.56 | 0.25–0.86 | ||||||

| Sylhet | 1 | - | ||||||

| Father’s occupation | Service | 1.33 | 1.14–1.52 | 42.8 | 0.002 | 0.3 | Small | |

| Skilled manual | 0.86 | 0.76–0.86 | ||||||

| Unskilled labour | 1.04 | 1.01–1.17 | ||||||

| Agricultural work | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1 | - | ||||||

| Wealth index | Richest | 1.04 | 1.02–1.06 | 60.2 | <0.001 | 0.3 | Small | |

| Richer | 0.93 | 0.89–0.97 | ||||||

| Middle | 0.82 | 0.72–0.92 | ||||||

| Poorer | 1.18 | 1.09–1.27 | ||||||

| Poorest | 1 | - | ||||||

| Overweight mother with wasted child | Father’s occupation | Service | 1.06 | 1.02–1.10 | 42.7 | 0.002 | 0.3 | Small |

| Skilled manual | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | ||||||

| Unskilled labour | 1.28 | 1.11–1.45 | ||||||

| Agricultural work | 1.43 | 1.19–1.67 | ||||||

| Unemployed | 1 | - | ||||||

| Wealth index | Richest | 0.57 | 0.28–0.86 | 53.1 | <0.001 | 0.3 | Small | |

| Richer | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | ||||||

| Middle | 1.68 | 0.75–1.95 | ||||||

| Poorer | 1.54 | 1.31–1.77 | ||||||

| Poorest | 1 | - | ||||||

| Overweight mother with anaemic child | Region | Barisal | 3.13 | 2.32–3.94 | 55.1 | 0.003 | 0.4 | Small |

| Chittagong | 0.92 | 0.86–0.98 | ||||||

| Dhaka | 1.29 | 1.11–1.47 | ||||||

| Khulna | 2.89 | 2.11–3.63 | ||||||

| Rajshahi | 2.68 | 1.97–3.39 | ||||||

| Rangpur | 1.26 | 1.09–1.43 | ||||||

| Sylhet | 1 | - | ||||||

| Drinking water | Pipe | 0.73 | 0.50–0.96 | 26.9 | 0.003 | 0.4 | Small | |

| Tube well | 0.65 | 0.34–0.95 | ||||||

| Rest | 1 | - |

References

- The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2017. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-I7695e.pdf&p=DevEx,5065.1 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- World Health Organization (WHO). The Double Burden of Malnutrition. Policy Brief. World Health Organization, 2017. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255413/WHO-NMH-NHD-17.3-eng.pdf;jsessionid=4209D4A56DC35E637DEBFF29354CEC5F?sequence=1 (accessed on 17 August 2018).

- Black, R.E.; Victora, C.G.; Walker, S.P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Christian, P.; de Onis, M.; Ezzati, M.; Grantham-McGregor, S.; Katz, J.; Martorell, R.; et al. Maternal and child undernutrition and overweight in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2013, 382, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubert, M.B.; Spaniol, A.M.; Segall-Corrêa, A.M.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Understanding the double burden of malnutrition in food insecure households in Brazil. Matern. Child Nutr. 2017, 13, e12347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamah-Levy, T.; Mundo-Rosas, V.; Morales-Ruan, C.; Cuevas-Nasu, L.; Méndez-Gómez-Humarán, I.; Pérez-Escamilla, R. Food insecurity and maternal-child nutritional status in Mexico: Cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Survey 2012. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, P.; Thow, A.M.; Abimbola, S.; Faruqui, N.; Negin, J. How food insecurity could lead to obesity in LMICs: When not enough is too much: A realist review of how food insecurity could lead to obesity in low- and middle-income countries. Health Promot. Int. 2017, 33, 812–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demographic and Health Survey. Wealth Index Construction. Available online: www.dhsprogram.com/topics/wealth-index/Wealth-Index-Construction.cfm (accessed on 15 July 2018).

- NIPORT Mitra and Associates, Macro International. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2011; National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, and Macro International: Dhaka, Bangladesh; Calverton, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Houser, R.F.; Must, A.; de Fulladolsa, P.P.; Bermudez, O.I. Socioeconomic disparities and the familial coexistence of child stunting and maternal overweight in Guatemala. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2012, 10, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barquera, S.; Peterson, K.E.; Must, A.; Rogers, B.L.; Flores, M.; Houser, R.; Monterrubio, E.; Rivera-Dommarco, J.A. Coexistence of maternal central adiposity and childstunting in Mexico. Int. J. Obes. 2007, 31, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrett, J.L.; Ruel, M.T. Stunted child-overweight mother pairs: Prevalence and association with economic development and urbanization. Food Nutr. Bull. 2005, 26, 209–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmiento, O.L.; Parra, D.C.; González, S.A.; González-Casanova, I.; Forero, A.Y.; Garcia, J. The dual burden of malnutrition in Colombia. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1628S–1635S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doak, C.M.; Adair, L.S.; Bentley, M.; Monteiro, C.; Popkin, B.M. The dual burden household and the nutrition transition paradox. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassett, M.N.; Romaguera, D.; Giménez, M.A. Prevalence and determinants of the dual burden of malnutrition at the household level in Puna and Quebrada of Humahuaca, Jujuy, Argentina. Nutr. Hosp. 2014, 29, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jef, L.L.; Jean-Pierre, H.; Teresa, G.; Ruel, M.T. Maternal education mitigates the negative effects of higher income on the double burden of child stunting and maternal overweight in rural Mexico. J. Nutr. 2014, 144, 765–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geok, L.; Zalilah, M.S. Dual forms of malnutrition in the same households in Malaysia-a case study among Malay rural households. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2003, 12, 427–438. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, S.V.; Ichiro, K.; George, D. Income inequality and the double burden of under- and over nutrition in India. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2007, 61, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddo, V.M.; Rah, J.H.; Semba, R.D.; Sun, K.; Akhter, N.; Sari, M.; De Pee, S.; Moench-Pfanner, R.; Bloem, M.; Kraemer, K. Predictors of maternal and child double burden of malnutrition in rural Indonesia and Bangladesh. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jehn, M.; Brewis, A. Paradoxical malnutrition in mother-child pairs: Untangling the phenomenon of over- and under-nutrition in underdeveloped economies. Econ. Hum. Biol. 2009, 7, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.M. Income Inequality in Bangladesh. In Proceedings of the 19th Biennial Conference “Rethinking Political Economy of Development” of the Bangladesh Economic Association Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh, Dhaka, 25–27 November 2014; Available online: http://bea-bd.org/site/images/pdf/063.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2018).

- Maps of the World. Available online: http://www.maps-of-the-world.net/maps-of-asia/maps-of-bangladesh/ (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- WHO Child Growth Standards. Available online: https://www.who.int/childgrowth/standards/Technical_report.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2018).

- Saibul, N.; Shariff, Z.M.; Lin, K.G.; Kandiah, M.; Ghani, N.A.; Rahman, H.A. Food variety score is associated with dual burden of malnutrition in Orang Asli (Malaysian indigenous peoples) households: Implications for health promotion. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 18, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Popkin, B.M. The nutrition transition and obesity in the developing world. J. Nutr. 2001, 131, 871S–873S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruel, M.T.; Haddad, L.; Garrett, J.L. Rapid urbanization and the challenges of obtaining food and nutrition security. In Nutrition and Health in Developing Countries; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 465–482. ISBN 978-1-59259-225-8. [Google Scholar]

- Quisumbing, A.R. Investments, Bequests, and Public Policy: Intergenerational Transfers and the Escape from Poverty. Chronic Poverty Research Centre Working Paper. 2007. Available online: http://www.chronicpoverty.org/uploads/publication_files/WP98_Quisumbing.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Shukla, H.C.; Gupta, P.C.; Mehta, H.C.; Hébert, J.R. Descriptive epidemiology of body mass index of an urban adult population in western India. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2002, 56, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). 2012. Available online: http://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/mdg/the-millennium-development-goals-report-2012.html (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Shafique, S.; Akhter, N.; Stallkamp, G.; de Pee, S.; Panagides, D.; Bloem, M.W. Trends of under-and overweight among rural and urban poor women indicate the double burden of malnutrition in Bangladesh. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2007, 36, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street Food, FAO. 1997. Available online: http://www.fao.org/fcit/food-processing/street-foods/enhtml (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Samapundo, S.; Climat, R.; Xhaferi, R.; Devlieghere, F. Food safety knowledge, attitudes and practices of street food vendors and consumers in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Food Control 2015, 50, 457–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Azim, H. Hygiene practices and food safety knowledge among street food vendors in Kashmir. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2015, 4, 723–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, A. Economic reforms, employment and poverty: Trends and options. Econ. Polit. Wkly. 1996, 31, 2459–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, B.; Bucci, G.A. On-the-job search in a developing country: An analysis based on Indian data on migrants. Econ. Dev. Cult. Chang. 1995, 43, 565–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, J.C.; Cleland, J. Self-reported symptoms of gynecological morbidity and their treatment in south India. Stud. Fam. Plann. 1995, 26, 203–216. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/2137846.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2018). [CrossRef]

- Brabin, B.J.; Romagosa, C.; Abdelgalil, S.; Menendez, C.; Verhoeff, F.H.; McGready, R.; Fischer, P.R. The sick placenta—The role of malaria. Placenta 2004, 25, 359–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M. Global nutrition dynamics: The world is shifting rapidly toward a diet linked with noncommunicable diseases. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Report. Controlling the Global Obesity Epidemic, 2003. Available online: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/obesity/en/ (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Monteiro, C.A.; Conde, W.L.; Lu, B.; Popkin, B.M. Obesity and inequities in health in the developing world. Int. J. Obes. 2004, 28, 1181–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A.; Roy, S.; Lundberg, R.; Guilbert, T.; Auger, A.; Blohowiak, S.; Coe, C.L.; Kling, P.J. Neonatal iron status is impaired by maternal obesity and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. J. Perinatol. 2014, 34, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroker-Lobos, M.F.; Pedroza-Tobías, A.; Pedraza, L.S.; Rivera, J.A. The double burden of undernutrition and excess body weight in Mexico. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1652S–1658S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleven, K.J.; Blohowiak, S.E.; Kling, P.J. Zinc protoporphyrin/heme in large-for-gestation newborns. Neonatology 2007, 92, 91–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.D.; Zhao, G.; Jiang, Y.P.; Zhou, M.; Xu, G.; Kaciroti, N.; Zhang, Z.; Lozoff, B. Maternal obesity during pregnancy is negatively associated with maternal and neonatal iron status. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 70, 918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero, B. A Nutrition Paradox—Underweight and Obesity in Developing Countries, 2005. Available online: http://www.pacifichealthsummit.org/downloads/Nutrition/A%20Nutrition%20Paradox.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2018).

- Ruel, M.T.; Alderman, H.; Maternal and Child Nutrition Study Group. Nutrition-sensitive interventions and programmes: How can they help to accelerate progress in improving maternal and child nutrition? Lancet 2013, 382, 536–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).