Repurposing Itraconazole in Combination with Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Cancer

Abstract

1. Introduction

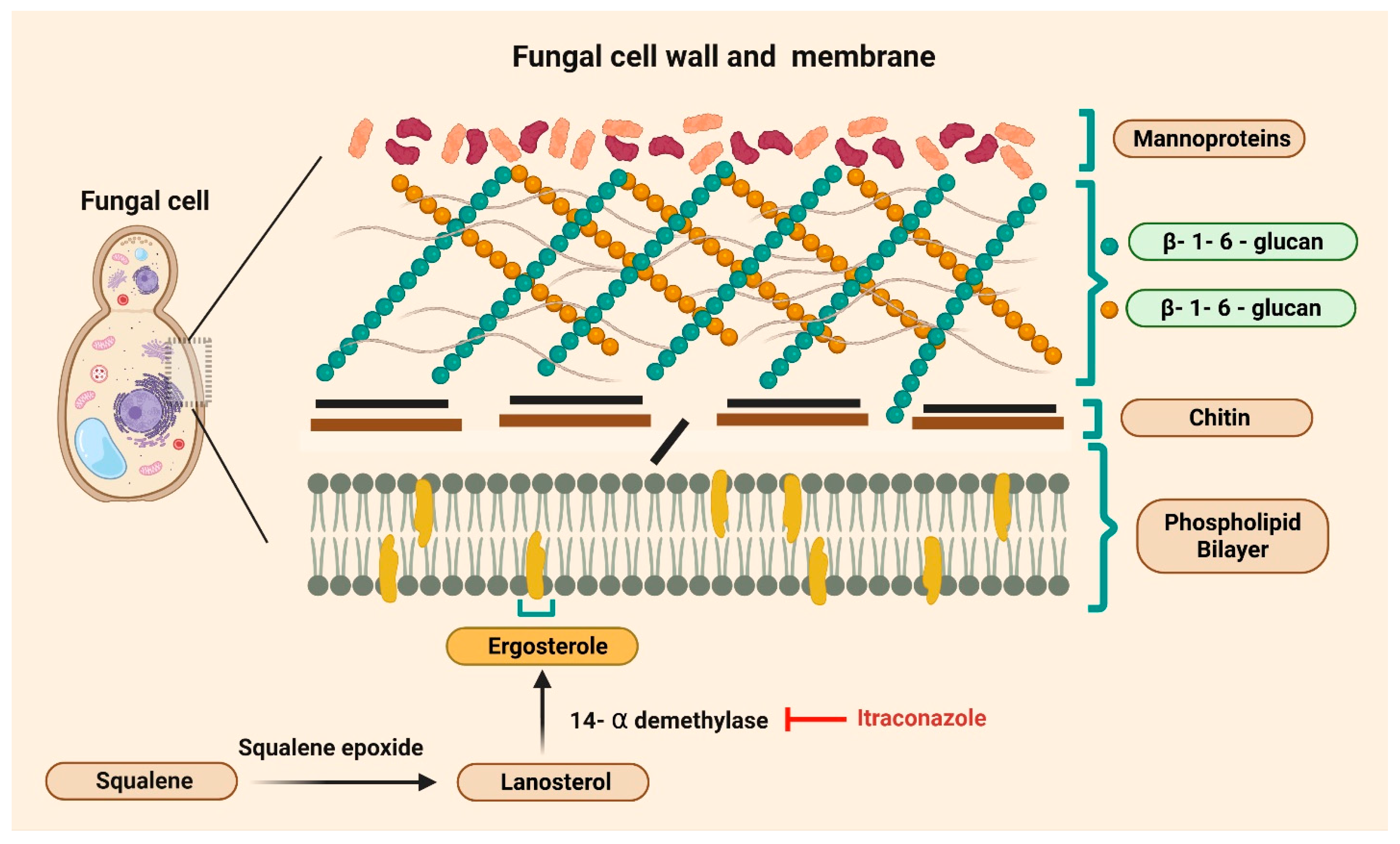

2. Drug Repurposing in Cancer Therapy

3. Repurposed Antifungals: Clinical Use and Mechanisms of Action

4. Experimental and Clinical Studies

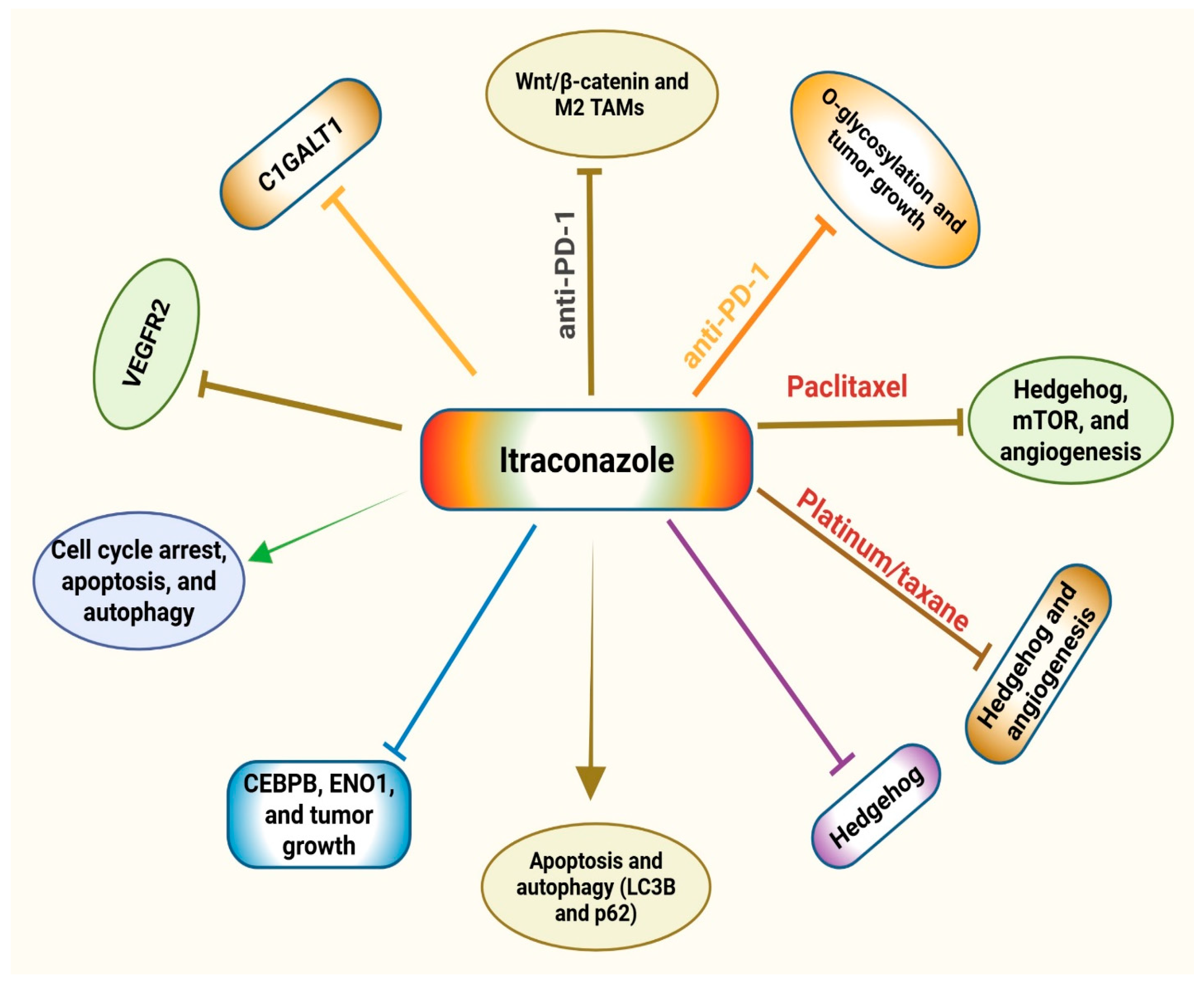

4.1. Experimental Studies

4.2. Clinical Studies

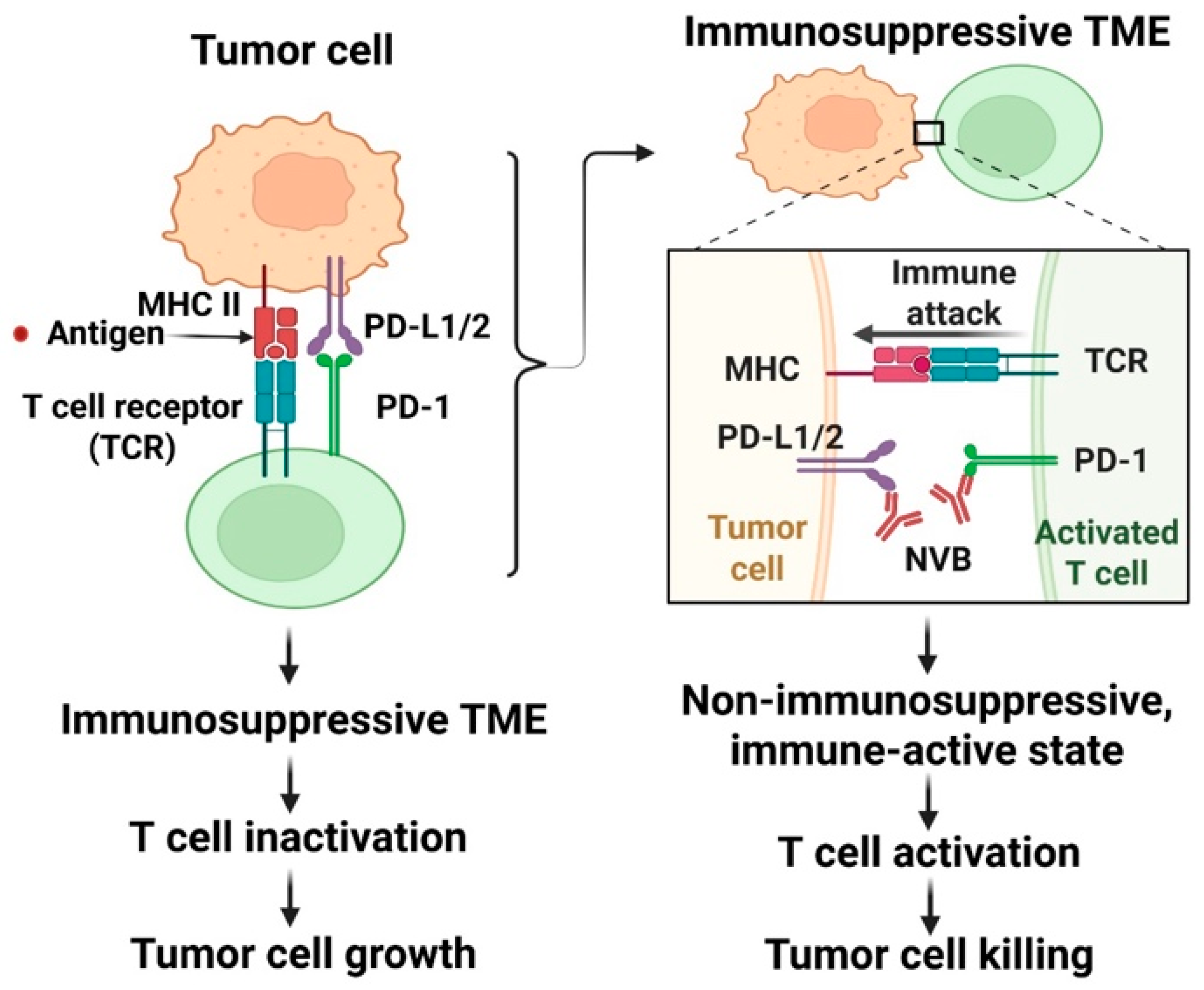

5. Immunotherapy and Anti-PD-1 Drugs

6. Combination Therapy

6.1. Experimental Studies Supporting Itraconazole’s Use in Combination Therapy

6.2. Clinical Studies Supporting Itraconazole’s Use in Combination Therapy

7. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ICs | Immune checkpoints |

| PD-1 | Programmed cell death protein 1 |

| PD-L1/2 | Programmed cell death ligand 1/2 |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| mTOR | Mammalian target of rapamycin |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung cancer |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CEBPB | CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Beta |

| ENO1 | Enolase 1 |

| Hh | Hedgehog |

| Smo | Smoothened |

| VEGFR2 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 |

| C1GALT1 | Core 1 β1,3-galactosyltransferase |

| HNC | Head and neck cancer |

| CTL | Cytotoxic T lymphocyte |

| IL-6 | Interleukin 6 |

| PSA | Prostate-specific antigen |

| PFS | Progression-free survival |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| LAG-3 | Lymphocyte-activation gene-3 |

| TIM-3 | T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain-containing protein 3 |

| PBMCs | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

References

- Schwartz, S.M. Epidemiology of Cancer. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancer. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer#:~:text=Key%20facts,and%20rectum%20and%20prostate%20cancers (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2024; American Cancer Society: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zafar, A.; Khatoon, S.; Khan, M.J.; Abu, J.; Naeem, A. Advancements and Limitations in Traditional Anti-Cancer Therapies: A Comprehensive Review of Surgery, Chemotherapy, Radiation Therapy, and Hormonal Therapy. Discov. Oncol. 2025, 16, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Sun, M.; Huang, H.; Jin, W.-L. Drug Repurposing for Cancer Therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pounds, R.; Leonard, S.; Dawson, C.; Kehoe, S. Repurposing Itraconazole for the Treatment of Cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E.S.; Heath, E.I.; Smith, D.C.; Rathkopf, D.; Blackford, A.L.; Danila, D.C.; King, S.; Frost, A.; Ajiboye, A.S.; Zhao, M.; et al. Repurposing Itraconazole as a Treatment for Advanced Prostate Cancer: A Noncomparative Randomized Phase II Trial in Men with Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Oncologist 2013, 18, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed, A.W.; Elbassiouny, M.; Elkhodary, D.A.; Shawki, M.A.; Saad, A.S. The Effect of Itraconazole on the Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Receiving Platinum-Based Chemotherapy: A Randomized Controlled Study. Med. Oncol. 2021, 38, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfab, C.; Schnobrich, L.; Eldnasoury, S.; Gessner, A.; El-Najjar, N. Repurposing of Antimicrobial Agents for Cancer Therapy: What Do We Know? Cancers 2021, 13, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Zou, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, K.; Lei, Y.; Yuan, K.; Li, Y.; Lan, J.; et al. Itraconazole Suppresses the Growth of Glioblastoma Through Induction of Autophagy: Involvement of Abnormal Cholesterol Trafficking. Autophagy 2014, 10, 1241–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftab, B.T.; Dobromilskaya, I.; Liu, J.O.; Rudin, C.M. Itraconazole Inhibits Angiogenesis and Tumor Growth in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 6764–6772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morad, G.; Helmink, B.A.; Sharma, P.; Wargo, J.A. Hallmarks of Response, Resistance, and Toxicity to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cell 2021, 184, 5309–5337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y.; Han, W. Lessons Learned from the Blockade of Immune Checkpoints in Cancer Immunotherapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2018, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, H.; Hagerling, C.; Werb, Z. Roles of the Immune System in Cancer: From Tumor Initiation to Metastatic Progression. Genes Dev. 2018, 32, 1267–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvez, A.; Choudhary, F.; Mudgal, P.; Khan, R.; Qureshi, K.A.; Farooqi, H.; Aspatwar, A. PD-1 and PD-L1: Architects of Immune Symphony and Immunotherapy Breakthroughs in Cancer Treatment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1296341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, A.; Sid Idris, F.; Anis Shaikh, H.; Vahora, I.; Moparthi, K.P.; Al Rushaidi, M.T.; Muddam, M.R.; Obajeun, O.A.; Jaramillo, A.P.; Khan, S. Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 (PD-1) and Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1 (PD-L1) Immunotherapy: A Promising Breakthrough in Cancer Therapeutics. Cureus 2023, 15, e44582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaafeen, B.H.; Ali, B.R.; Elkord, E. Resistance Mechanisms to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Updated Insights. Mol. Cancer 2025, 24, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Ye, Y.; Wang, C.; Pang, G.; Liu, W.; Liu, A.; Zhao, C.; Hao, X. Strategies to Enhance the Therapeutic Efficacy of Anti-PD-1 Antibody, Anti-PD-L1 Antibody and Anti-CTLA-4 Antibody in Cancer Therapy. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 22, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.B.; Smith, E.R.; Koutouratsas, V.; Chen, Z.-S.; Xu, X.-X. The Persistent Power of the Taxane/Platin Chemotherapy. Cancers 2025, 17, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sertkaya, A.; Beleche, T.; Jessup, A.; Sommers, B.D. Costs of Drug Development and Research and Development Intensity in the US, 2000–2018. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2415445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.; Vayer, P.; Tanwar, S.; Poyet, J.-L.; Tsaioun, K.; Villoutreix, B.O. Drug Discovery and Development: Introduction to the General Public and Patient Groups. Front. Drug Discov. 2023, 3, 1201419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Gao, W.; Hu, H.; Zhou, S. Why 90% of Clinical Drug Development Fails and How to Improve It? Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 3049–3062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Li, J.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y. Review of Drug Repositioning Approaches and Resources. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 1232–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashburn, T.T.; Thor, K.B. Drug Repositioning: Identifying and Developing New Uses for Existing Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schein, C.H. Repurposing Approved Drugs for Cancer Therapy. Br. Med. Bull. 2021, 137, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weth, F.R.; Hoggarth, G.B.; Weth, A.F.; Paterson, E.; White, M.P.J.; Tan, S.T.; Peng, L.; Gray, C. Unlocking Hidden Potential: Advancements, Approaches, and Obstacles in Repurposing Drugs for Cancer Therapy. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 130, 703–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huff, C.A.; Matsui, W.; Smith, B.D.; Jones, R.J. The Paradox of Response and Survival in Cancer Therapeutics. Blood 2006, 107, 431–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, N.; Grimshaw, A.A.; Axson, S.A.; Choe, S.H.; Miller, J.E. Drug Repurposing: A Systematic Review on Root Causes, Barriers and Facilitators. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantziarka, P.; Vandeborne, L.; Bouche, G. A Database of Drug Repurposing Clinical Trials in Oncology. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 790952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohi-ud-din, R.; Chawla, A.; Sharma, P.; Mir, P.A.; Potoo, F.H.; Reiner, Ž.; Reiner, I.; Ateşşahin, D.A.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Mir, R.H.; et al. Repurposing Approved Non-Oncology Drugs for Cancer Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanisms, Efficacy, and Clinical Prospects. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2023, 28, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, A.A.; Kasi, A. Genetics, Cancer Cell Cycle Phases. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Tufail, M.; Jiang, C.-H.; Li, N. Altered Metabolism in Cancer: Insights into Energy Pathways and Therapeutic Targets. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Drug Resistance and Combating Drug Resistance in Cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Fang, Y.; Qu, L.; Lin, A.; Luo, P.; Jiang, A.; et al. Drug Resistance in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Emerging Treatment Strategies. Mol. Biomed. 2025, 6, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srirangam, A.; Milani, M.; Mitra, R.; Guo, Z.; Rodriguez, M.; Kathuria, H.; Fukuda, S.; Rizzardi, A.; Schmechel, S.; Skalnik, D.G.; et al. The Human Immunodeficiency Virus Protease Inhibitor Ritonavir Inhibits Lung Cancer Cells, in Part, by Inhibition of Survivin. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011, 6, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saraei, P.; Asadi, I.; Kakar, M.A.; Moradi-Kor, N. The Beneficial Effects of Metformin on Cancer Prevention and Therapy: A Comprehensive Review of Recent Advances. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, 11, 3295–3313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, K.; Ren, Z.; Yin, D.; Zhou, Y. Metformin as Anticancer Agent and Adjuvant in Cancer Combination Therapy: Current Progress and Future Prospect. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 44, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrick, E.J.; Patel, P.; Hashmi, M.F. Antifungal Ergosterol Synthesis Inhibitor. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kurn, H.; Wadhwa, R. Itraconazole. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Maertens, J.A. History of the Development of Azole Derivatives. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantziarka, P. Repurposing Drugs in Oncology (ReDO)—Itraconazole as an Anti-Cancer Agent. Ecancermedicalscience 2015, 9, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Tang, J.Y.; Gong, R.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.J.; Clemons, K.V.; Chong, C.R.; Chang, K.S.; Fereshteh, M.; Gardner, D.; et al. Itraconazole, a Commonly Used Antifungal That Inhibits Hedgehog Pathway Activity and Cancer Growth. Cancer Cell 2010, 17, 388–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Liu, X.; Cai, L.; Yan, J.; Li, L.; Dong, H.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X. Itraconazole Promotes Melanoma Cells Apoptosis via Inhibiting Hedgehog Signaling Pathway-Mediated Autophagy. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1545243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, G.K.; Kwon, G.P.; Bailey-Healy, I.; Mirza, A.; Sarin, K.; Oro, A.; Tang, J.Y. Topical Itraconazole for the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma in Patients with Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome or High-Frequency Basal Cell Carcinomas. JAMA Dermatol 2019, 155, 1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, C.H.; Ryu, J.-Y.; Cho, Y.-J.; Jeon, H.-K.; Choi, J.-J.; Ylaya, K.; Lee, Y.-Y.; Kim, T.-J.; Chung, J.-Y.; Hewitt, S.M.; et al. The Anti-Cancer Effects of Itraconazole in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marastoni, S.; Madariaga, A.; Pesic, A.; Nair, S.N.; Li, Z.J.; Shalev, Z.; Ketela, T.; Colombo, I.; Mandilaras, V.; Cabanero, M.; et al. Repurposing Itraconazole and Hydroxychloroquine to Target Lysosomal Homeostasis in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer. Cancer Res. Commun. 2022, 2, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, L.; Chu, F.; Wu, H.; Xiao, X.; Ye, J.; Li, K. Itraconazole Inhibits Tumor Growth via CEBPB-mediated Glycolysis in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Sci. 2024, 115, 1154–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Chuang, Y.; Wu, H.; Hsu, C.; Lin, N.; Huang, M.; Lou, P. Targeting Tumor O-glycosylation Modulates Cancer–Immune-cell Crosstalk and Enhances Anti-PD-1 Immunotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer. Mol. Oncol. 2024, 18, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.-W.; Chou, Y.-M.; Li, C.-L.; Liao, E.-C.; Huang, H.-S.; Yin, C.-H.; Chen, C.-L.; Yu, S.-J. Itraconazole Improves Survival Outcomes in Patients with Colon Cancer by Inducing Autophagic Cell Death and Inhibiting Transketolase Expression. Oncol. Lett. 2021, 22, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nacev, B.A.; Grassi, P.; Dell, A.; Haslam, S.M.; Liu, J.O. The Antifungal Drug Itraconazole Inhibits Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR2) Glycosylation, Trafficking, and Signaling in Endothelial Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 44045–44056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, G.; Liu, M.; Wang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Mei, H.; Li, D.; Liu, W. Itraconazole Exerts Its Anti-Melanoma Effect by Suppressing Hedgehog, Wnt, and PI3K/MTOR Signaling Pathways. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 28510–28525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.-C.; Chien, P.-H.; Wu, H.-Y.; Chen, S.-T.; Juan, H.-F.; Lou, P.-J.; Huang, M.-C. C1GALT1 Predicts Poor Prognosis and Is a Potential Therapeutic Target in Head and Neck Cancer. Oncogene 2018, 37, 5780–5793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, G.B.; Honorato, J.R.; de Lopes, G.P.F.; Spohr, T.C.L.d.S.E. A Highlight on Sonic Hedgehog Pathway. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Kim, J.; Spaunhurst, K.; Montoya, J.; Khodosh, R.; Chandra, K.; Fu, T.; Gilliam, A.; Molgo, M.; Beachy, P.A.; et al. Open-Label, Exploratory Phase II Trial of Oral Itraconazole for the Treatment of Basal Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 745–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Hong, H.; Kim, W.; Friedlander, T.W.; Fong, L.; Lin, A.M.; Small, E.J.; Dhawan, M.S.; Wei, X.X.; Rodvelt, T.J.; et al. A Phase II Study of Itraconazole in Biochemically Recurrent Prostate Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, D.E.; Putnam, W.C.; Fattah, F.J.; Kernstine, K.H.; Brekken, R.A.; Pedrosa, I.; Skelton, R.; Saltarski, J.M.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Leff, R.D.; et al. Concentration-Dependent Early Antivascular and Antitumor Effects of Itraconazole in Non–Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 6017–6027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. The History and Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy: Understanding the Characteristics of Tumor-Infiltrating Immune Cells and Their Therapeutic Implications. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swann, J.B.; Smyth, M.J. Immune Surveillance of Tumors. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Lanier, L.L. Natural Killer Cells and Cancer. Adv. Cancer Res. 2003, 90, 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Lostao, L.; Anel, A.; Pardo, J. How Do Cytotoxic Lymphocytes Kill Cancer Cells? Clin. Cancer Res. 2015, 21, 5047–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGranahan, N.; Swanton, C. Clonal Heterogeneity and Tumor Evolution: Past, Present, and the Future. Cell 2017, 168, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, S.A.; Patel, V.P.; Bhosle, K.P.; Nagare, S.D.; Thombare, K.C. The Tumor Microenvironment: Shaping Cancer Progression and Treatment Response. J. Chemother. 2025, 37, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, S.P.; Ming, L.C.; Dhaliwal, J.S.; Gupta, M.; Ardianto, C.; Goh, K.W.; Hussain, Z.; Shafqat, N. Role of Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancers 2022, 14, 5205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munari, E.; Mariotti, F.R.; Quatrini, L.; Bertoglio, P.; Tumino, N.; Vacca, P.; Eccher, A.; Ciompi, F.; Brunelli, M.; Martignoni, G.; et al. PD-1/PD-L1 in Cancer: Pathophysiological, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaab, H.O.; Sau, S.; Alzhrani, R.; Tatiparti, K.; Bhise, K.; Kashaw, S.K.; Iyer, A.K. PD-1 and PD-L1 Checkpoint Signaling Inhibition for Cancer Immunotherapy: Mechanism, Combinations, and Clinical Outcome. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, J. Adverse Effects of Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 Therapy in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 554313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Kaestner, V. Nivolumab and Pembrolizumab: Monoclonal Antibodies against Programmed Cell Death-1 (PD-1) That Are Interchangeable. Semin. Oncol. 2017, 44, 132–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Chen, M.; Nie, H.; Yuan, Y. PD-1 and PD-L1 in Cancer Immunotherapy: Clinical Implications and Future Considerations. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2019, 15, 1111–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat Mokhtari, R.; Homayouni, T.S.; Baluch, N.; Morgatskaya, E.; Kumar, S.; Das, B.; Yeger, H. Combination Therapy in Combating Cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 38022–38043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, T.A.; Omlin, A.; de Bono, J.S. Development of Therapeutic Combinations Targeting Major Cancer Signaling Pathways. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1592–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, S.S.; Ibrahim, W.N. Cancer Resistance to Immunotherapy: Comprehensive Insights with Future Perspectives. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pascual, J.; Ayuso-Sacido, A.; Belda-Iniesta, C. Drug Resistance in Cancer Immunotherapy: New Strategies to Improve Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapies. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 980–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfarouk, K.O.; Stock, C.-M.; Taylor, S.; Walsh, M.; Muddathir, A.K.; Verduzco, D.; Bashir, A.H.H.; Mohammed, O.Y.; Elhassan, G.O.; Harguindey, S.; et al. Resistance to Cancer Chemotherapy: Failure in Drug Response from ADME to P-Gp. Cancer Cell Int. 2015, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; Han, L. Itraconazole Inhibits the Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway to Induce Tumor-Associated Macrophages Polarization to Enhance the Efficacy of Immunotherapy in Endometrial Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2025, 15, 1590095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porazinski, S.; Man, J.; Chacon-Fajardo, D.; Yim, H.; El-Omar, E.; Joshua, A.; Pajic, M. Abstract C017: The Anti-Fungal Itraconazole Improves Immunotherapy Efficacy in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma by Reversing the Immune-Suppressive Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2024, 84, C017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C.M.; Brahmer, J.R.; Juergens, R.A.; Hann, C.L.; Ettinger, D.S.; Sebree, R.; Smith, R.; Aftab, B.T.; Huang, P.; Liu, J.O. Phase 2 Study of Pemetrexed and Itraconazole as Second-Line Therapy for Metastatic Nonsquamous Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2013, 8, 619–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubamoto, H.; Sonoda, T.; Yamasaki, M.; Inoue, K. Impact of Combination Chemotherapy with Itraconazole on Survival of Patients with Refractory Ovarian Cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 2481–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, K.; Tsubamoto, H.; Isono-Nakata, R.; Sakata, K.; Nakagomi, N. Itraconazole Treatment of Primary Malignant Melanoma of the Vagina Evaluated Using Positron Emission Tomography and Tissue CDNA Microarray: A Case Report. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Poll, T.; van de Veerdonk, F.L.; Scicluna, B.P.; Netea, M.G. The Immunopathology of Sepsis and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017, 17, 407–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patricio, P.; Paiva, J.A.; Borrego, L.M. Immune Response in Bacterial and Candida Sepsis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2019, 9, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spec, A.; Shindo, Y.; Burnham, C.-A.D.; Wilson, S.; Ablordeppey, E.A.; Beiter, E.R.; Chang, K.; Drewry, A.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S. T Cells from Patients with Candida Sepsis Display a Suppressive Immunophenotype. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinghoff, S.C.; Thelen, M.; Bruns, C.; Garcia-Marquez, M.; Hartmann, P.; Lammertz, T.; Lehmann, J.; Nowag, A.; Stemler, J.; Wennhold, K.; et al. T-Cells of Invasive Candidiasis Patients Show Patterns of T-Cell-Exhaustion Suggesting Checkpoint Blockade as Treatment Option. J. Infect. 2022, 84, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shindo, Y.; McDonough, J.S.; Chang, K.C.; Ramachandra, M.; Sasikumar, P.G.; Hotchkiss, R.S. Anti-PD-L1 Peptide Improves Survival in Sepsis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 208, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.C.; Burnham, C.-A.; Compton, S.M.; Rasche, D.P.; Mazuski, R.; SMcDonough, J.; Unsinger, J.; Korman, A.J.; Green, J.M.; Hotchkiss, R.S. Blockade Ofthe Negative Co-Stimulatory Molecules PD-1 and CTLA-4 Improves Survival in Primary and Secondary Fungal Sepsis. Crit. Care 2013, 17, R85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, A.; Noel Alexander F, H.; Muzumder, S.; Srikantia, N.; Udayashankar, A.H. Sepsis Surveillance in Patients with Head-and-Neck Cancer Undergoing Chemo-Radiation. Support. Care Cancer 2024, 32, 724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, R.; Casella, T. Healthcare-Associated Infections in Patients Who Are Immunosuppressed Due to Chemotherapy Treatment: A Narrative Review. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2022, 16, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupp, J.; Culakova, E.; Poniewierski, M.S.; Dale, D.C.; Lyman, G.H.; Crawford, J. Analysis of Factors Associated with In-Hospital Mortality in Lung Cancer Chemotherapy Patients with Neutropenia. Clin. Lung Cancer 2018, 19, e163–e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, C.; Dingemanse, J.; Meyer Zu Schwabedissen, H.E.; Fonseca, M.; Sidharta, P.N. The Effect of Itraconazole, a Strong CYP3A4 Inhibitor, on the Pharmacokinetics of the First-in-Class ACKR3/CXCR7 Antagonist, ACT-1004-1239. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e13883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergagnini-Kolev, M.; Kane, K.; Templeton, I.E.; Curran, A.K. Evaluation of the Potential for Drug-Drug Interactions with Inhaled Itraconazole Using Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling, Based on Phase 1 Clinical Data. AAPS J. 2023, 25, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hau, C.S.; Tada, Y.; Kanda, N.; Watanabe, S. Immunoresponses in Dermatomycoses. J. Dermatol. 2015, 42, 236–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Lei, J.; Suo, C. Fungi and Cancer: Unveiling the Complex Role of Fungal Infections in Tumor Biology and Therapeutic Resistance. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1596688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurster, S.; Watowich, S.S.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Checkpoint Inhibitors as Immunotherapy for Fungal Infections: Promises, Challenges, and Unanswered Questions. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1018202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cancer Type | Study Type | Study Design and Patient Demographics | Key Results | Proposed Mechanism/Pathway | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Xenograft models | NSCLC xenograft models derived from treatment-naïve patient tumors; itraconazole-treated cells compared with untreated controls | Itraconazole inhibited angiogenesis and slowed tumor growth | Suppression of endothelial cell function and reduced tumor vascularization | [11] |

| Advanced colorectal cancer | Itraconazole intraperitoneal injections | Xenograft models of CRC-bearing mice | Itraconazole significantly reduced tumor volume and weight | Itraconazole disrupts tumor energy metabolism by remodeling gene expression and cellular composition; it decreases expression of CEDPB and suppresses ENO1 | [48] |

| Colon cancer | Clinical data and in vitro studies | Retrospective cohort of colon cancer patients treated or not treated with itraconazole; complementary in vitro assays on colon cancer cell lines | Itraconazole improved five-year survival and reduced cell viability and colony formation | Induction of cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, and autophagy | [50] |

| Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | Mouse xenograft models and HNSCC cells | Using HNSCC cells and mouse xenograft models that overexpressed C1GALT1 | Itraconazole significantly inhibited tumor growth and C1GALT1 expression | Itraconazole inhibits C1GALT1, a molecule that predicts poor prognosis in HNSCC | [53] |

| Cancer Type | Study Type | Study Design and Patient Demographics | Key Results | Proposed Mechanism/Pathway | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | Phase II clinical trial | Noncomparative randomized phase II trial in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer | High-dose itraconazole significantly delayed disease progression | Inhibition of the Hedgehog signaling pathway | [7] |

| Basal cell carcinoma | Open-label, proof-of-concept phase II trial | Patients with ≥1 basal cell carcinoma tumor > 4 mm in diameter received oral itraconazole 200 mg/day for 1 month or 100 mg twice daily for about 2 months | Itraconazole reduced tumor size, proliferation, and Hedgehog pathway activity | Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling | [55] |

| Biochemically recurrent prostate cancer | Phase II trial | Itraconazole 300 mg orally twice daily until PSA progression, toxicity, or patient withdrawal | 47% of patients had a PSA decline by week 12; 5% had > 50% PSA reduction. Common adverse effects included edema, fatigue, hypertension, and hypokalemia | Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling | [56] |

| NSCLC patients scheduled for surgical resection | Phase 0, window-of-opportunity trial | Itraconazole 300 mg orally twice daily for 10–14 days before surgery | Decreased tumor perfusion and microvessel density; higher itraconazole levels correlated with greater tumor volume reduction and anti-angiogenic effects. Adverse effects were low-grade, reversible, and manageable, including fatigue, nausea, and elevated transaminase levels | Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling, alteration of tumor metabolism, inhibition of angiogenesis | [57] |

| Cancer Type | Intervention | Cell/Animal Model | Key Results | Proposed Mechanism/Pathway | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head and neck cancer | Itraconazole combined with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy | Syngeneic mouse models of HNC | Combination therapy effectively suppressed tumor growth | Itraconazole inhibits O-glycosylation, enhancing immunosuppressive effects and augmenting the activity of anti-PD-1 therapy | [49] |

| Epithelial ovarian cancer | Itraconazole combined with paclitaxel | Ovarian cancer cell lines, mouse xenografts, and patient-derived xenograft models | Combination therapy reduced tumor weight, microvessel density, and angiogenesis more than paclitaxel alone | Inhibition of Hedgehog and mTOR signaling, anti-angiogenic effects | [46] |

| Colon adenocarcinoma | Itraconazole treatment; extends prior retrospective evidence that itraconazole improves 5-year survival in patients with late-stage colon cancer receiving chemotherapy | Human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines (COLO 205) | Itraconazole induced apoptosis and autophagy and promoted cell cycle arrest | Itraconazole increases cleaved caspase-3 and Bax expression and activates autophagy through LC3B activation and p62 involvement | [50] |

| Endometrial cancer | Itraconazole combined with anti-PD-1 immunotherapy | Syngeneic mouse model of EC | Combination therapy effectively suppressed tumor growth | Itraconazole and anti-PD-1 synergistically inhibited Wnt/β-catenin signaling and promoted the polarization of the M2 phenotype of TAMs to the M1 phenotype | [75] |

| Patient Population | Design | Intervention | Outcomes | Limitations/Toxicities | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced NSCLC patients receiving platinum-based chemotherapy | Randomized controlled study | Addition of itraconazole to standard platinum-based chemotherapy vs. chemotherapy alone | 1-year progression-free survival and 1-year overall survival were significantly improved in the itraconazole group | Itraconazole was well tolerated; one patient developed cardiotoxicity; the benefits were modest | [8] |

| Progressive non-squamous NSCLC after prior cytotoxic therapy | Phase II study | Pemetrexed IV with or without 200 mg oral itraconazole daily for 21 days | 67% of patients were progression-free in the combination group vs. 29% with pemetrexed alone; both overall survival and median progression-free survival were longer with itraconazole | No significant differences in toxicities between groups | [77] |

| Refractory ovarian cancer | Retrospective study | Patients with refractory ovarian cancer receiving platinum/taxane chemotherapy with or without itraconazole | Itraconazole combination improved survival compared with chemotherapy alone | Synergistic effect with chemotherapy; potential Hedgehog and angiogenesis pathway inhibition | [78] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zonfa, C.E.; Thyagarajan, A.; Sahu, R.P. Repurposing Itraconazole in Combination with Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Cancer. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010055

Zonfa CE, Thyagarajan A, Sahu RP. Repurposing Itraconazole in Combination with Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Cancer. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010055

Chicago/Turabian StyleZonfa, Camille E., Anita Thyagarajan, and Ravi P. Sahu. 2026. "Repurposing Itraconazole in Combination with Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Cancer" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010055

APA StyleZonfa, C. E., Thyagarajan, A., & Sahu, R. P. (2026). Repurposing Itraconazole in Combination with Chemotherapy and Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor for Cancer. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010055