Development, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of Urdu Pain Neuroscience Education Materials for Low Back Pain in Pakistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

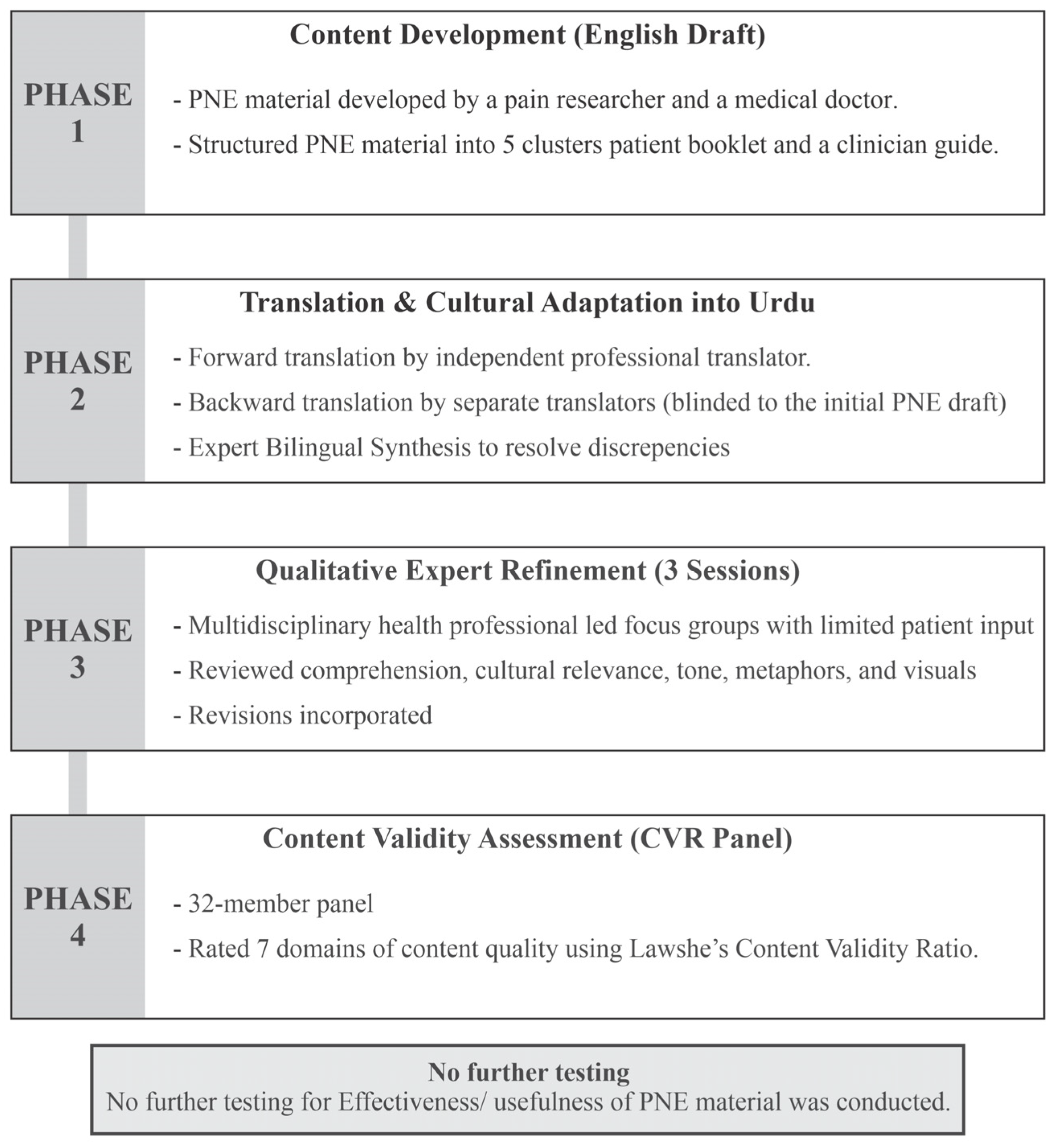

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LBP | Low back pain |

| PNE | Pain neuroscience education |

| CVR | Content validity ratio |

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Lopez, A.D. Measuring the global burden of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 369, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, C.G.; Williams, C.; Lin, C.; Latimer, J. Managing low back pain in primary care. Aust. Prescr. 2011, 34, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, G.L.; Butler, D.S. Fifteen years of explaining pain: The past, present, and future. J. Pain 2015, 16, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegner, H.; Frederiksen, P.; Esbensen, B.A.; Juhl, C. Neurophysiological Pain education for patients with chronic low back pain. Clin. J. Pain 2018, 34, 778–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, E.K.-Y.; Chen, L.; Simic, M.; Ashton-James, C.E.; Comachio, J.; Wang, D.X.M.; Hayden, J.A.; Ferreira, M.L.; Ferreira, P.H. Psychological interventions for chronic, non-specific low back pain: Systematic review with network meta-analysis. BMJ 2022, 376, e067718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Puentedura, E.J.; Zimney, K.; Schmidt, S. Know Pain, Know gain? A Perspective on Pain Neuroscience Education in Physical therapy. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2016, 46, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orhan, C.; Van Looveren, E.; Cagnie, B.; Mukhtar, N.B.; Lenoir, D.; Meeus, M. Are pain beliefs, cognitions, and behaviors influenced by race, ethnicity, and culture in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain: A Systematic review. Pain Physician 2018, 21, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira-Valente, M.A.; Ribeiro, J.L.P.; Jensen, M.P.; Almeida, R. Coping with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Portugal and in the United States: A Cross-Cultural Study. Pain Med. 2011, 12, 1470–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brod, M.; Tesler, L.E.; Christensen, T.L. Qualitative research and content validity: Developing best practices based on science and experience. Qual. Life Res. 2009, 18, 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orhan, C.; Cagnie, B.; Favoreel, A.; Van Looveren, E.; Akel, U.; Mukhtar, N.B.; De Meulemeester, K.; Pas, R.; Lenoir, D.; Meeus, M. Development of culturally sensitive Pain Neuroscience Education for first-generation Turkish patients with chronic pain: A modified Delphi study. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2018, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, N.B.; Meeus, M.; Gursen, C.; Mohammed, J.; Dewitte, V.; Cagnie, B. Development of culturally sensitive pain neuroscience education materials for Hausa-speaking patients with chronic spinal pain: A modified Delphi study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Jensen, M.P.; Moseley, G.L.; Abbott, J.H. Results of a feasibility randomised clinical trial on pain education for low back pain in Nepal: The Pain Education in Nepal-Low Back Pain (PEN-LBP) feasibility trial. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e026874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaton, D.E.; Bombardier, C.; Guillemin, F.; Ferraz, M.B. Guidelines for the process of Cross-Cultural adaptation of Self-Report measures. Spine 2000, 25, 3186–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terwee, C.B.; Mokkink, L.B.; Knol, D.L.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Bouter, L.M.; De Vet, H.C.W. Rating the methodological quality in systematic reviews of studies on measurement properties: A scoring system for the COSMIN checklist. Qual. Life Res. 2011, 21, 651–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawshe, C.H. A Quantitative Approach to Content Validity1. Pers. Psychol. 1975, 28, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayre, C.; Scally, A.J. Critical Values for Lawshe’s Content Validity Ratio. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2013, 47, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, G.L.; Leake, H.B.; Beetsma, A.J.; Watson, J.A.; Butler, D.S.; Van Der Mee, A.; Stinson, J.N.; Harvie, D.; Palermo, T.M.; Meeus, M.; et al. Teaching Patients About Pain: The Emergence of Pain Science Education, its Learning Frameworks and Delivery Strategies. J. Pain 2023, 25, 104425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, H.B.; Mardon, A.; Stanton, T.R.; Harvie, D.S.; Butler, D.S.; Karran, E.L.; Wilson, D.; Booth, J.; Barker, T.; Wood, P.; et al. Key Learning Statements for Persistent Pain Education: An iterative analysis of consumer, clinician and researcher perspectives and development of public messaging. J. Pain 2022, 23, 1989–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.M.D.; Bernal, G. Frameworks, models, and guidelines for cultural adaptation. In American Psychological Association eBooks; The American Psychological Association (APA): Washington, DC, USA, 2012; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darlow, B.; Perry, M.; Mathieson, F.; Stanley, J.; Melloh, M.; Marsh, R.; Baxter, G.D.; Dowell, A. The development and exploratory analysis of the Back Pain Attitudes Questionnaire (Back-PAQ). BMJ Open 2014, 4, e005251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, K.; Johnston, M. Validation of the Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire, its sensitivity as a measure of change following treatment and its relationship with other aspects of the chronic pain experience. Physiother. Theory Pract. 1997, 13, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waddell, G.; Newton, M.; Henderson, I.; Somerville, D.; Main, C.J. A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 1993, 52, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, M.J.L.; Bishop, S.R.; Pivik, J. The Pain Catastrophizing Scale: Development and validation. Psychol. Assess. 1995, 7, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, J.; Spencer, L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Analyzing Qualitative Data; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiger, B.; Rathleff, M.S.; Ickmans, K.; Rheel, E.; Straszek, C.L. Keeping It Simple—Pain Science Education for Patients with Chronic Pain Referred to Community-Based Rehabilitation: Translation, Adaptation, and Clinical Feasibility Testing of PNE4Adults. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J. Intricacies of good communication in the context of pain. Pain 2015, 156, 199–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, S.; Patel, S. Cultural influences on pain. Rev. Pain 2008, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Triandis, H.C. Individualism and Collectivism; Westview Press: Boulder, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, P.; Ai, A.L.; Aydin, N.; Frey, D.; Haslam, S.A. The Relationship between Religious Identity and Preferred Coping Strategies: An Examination of the Relative Importance of Interpersonal and Intrapersonal Coping in Muslim and Christian Faiths. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2010, 14, 365–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, A.E.; Hissey, L.; Milgate, S. Exploring thoughts about pain and pain management: Interviews with South Asian community members in the UK. Musculoskelet. Care 2019, 17, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Zimney, K.; O’Hotto, C.; Hilton, S. The clinical application of teaching people about pain. Physiother. Theory Pract. 2016, 32, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.U.; Malhotra, A.; Cameron, M. Beliefs, Treatment Use, Preferences, and Provider Choice for Low Back Pain Among Adults of Pakistani Origin: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2025; submitted under review. [Google Scholar]

- Meherali, S.; Punjani, N.S.; Mevawala, A. Health literacy Interventions to improve health outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income countries. HLRP Health Lit. Res. Pract. 2020, 4, e251–e266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louw, A.; Diener, I.; Landers, M.R.; Zimney, K.; Puentedura, E.J. Three-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial comparing preoperative neuroscience education for patients undergoing surgery for lumbar radiculopathy. J. Spine Surg. 2016, 2, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.N.U.; Malhotra, A.; Cameron, M. Attitudes, Beliefs, and Clinical Decision-Making Towards Low Back Pain: A Cross-Sectional Study of Pakistani Medical Practitioners, Physiotherapists, and Exercise Professionals. Musculoskelet. Care, 2025; submitted under review. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.N.U.; Malhotra, A.; Cameron, M. Low back pain in Pakistan: A scoping review of epidemiology and treatment approaches. J. Asian Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 898–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroncini, A.; Maffulli, N.; Manocchio, N.; Bossa, M.; Foti, C.; Schäfer, L.; Klimuch, A.; Migliorini, F. Active and passive physical therapy in patients with chronic low-back pain: A level I Bayesian network meta-analysis. J. Orthop. Traumatol. 2025, 26, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlong, B.; Frey, M.; Davidson, S.; Ferreira, G.; Etchegary, H.; Aubrey-Bassler, K.; Hall, A. Assessing patient education materials about low back pain for understandability, actionability, quality, readability, accuracy, comprehensiveness, and coverage of information about patients’ needs. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2025, 80, 103430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellegrini, G.; Lovati, C. Stakeholders’ engagement for improved health outcomes: A research brief to design a tool for better communication and participation. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1536753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Street, R.L.; Makoul, G.; Arora, N.K.; Epstein, R.M. How does communication heal? Pathways linking clinician–patient communication to health outcomes. Patient Educ. Couns. 2009, 74, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, R.; Mahboob, U.; Khan, R.A.; Anjum, A. Impact of language barriers in doctor—Patient relationship: A Qualitative study. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 39, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, Y.Z.; Chou, L.; Au, R.T.; Seneviwickrama, K.M.D.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Briggs, A.M.; Sullivan, K.; Urquhart, D.M.; Wluka, A.E. People with low back pain want clear, consistent and personalised information on prognosis, treatment options and self-management strategies: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2019, 65, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comachio, J.; Eyles, J.; Ferreira, P.H.; Ho, E.K.-Y.; Beckenkamp, P.R. Digital storytelling for low back pain: A strategy to communicate problems and influence policy. J. Public Health 2025, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Category | n (%) or Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder group | Total | 32 (100) |

| Physiotherapists | 8 (25.0) | |

| Medical practitioners | 6 (18.8) | |

| Exercise professionals | 8 (25.0) | |

| Individuals with LBP | 10 (31.2) | |

| Clinical experience (years) | HCPs managing back pain (n = 22) | 9.4 ± 5.8 years |

| Age (years) | Overall panel | 41.2 ± 10.6 |

| Healthcare professionals | 39.8 ± 9.7 | |

| Individuals with LBP | 44.1 ± 11.9 | |

| Back pain duration (years) | Individuals with LBP (n = 10) | 6.3 ± 4.1 |

| Validation Domain | Cluster 1 | Cluster 2 | Cluster 3 | Cluster 4 | Cluster 5 | Mean CVR (±SD) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content accuracy and clinical relevance | 0.75 | 0.875 | 0.875 | 0.9375 | 0.875 | 0.86 ± 0.07 | High agreement |

| Clarity and readability | 0.625 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.6875 | 0.71 ± 0.05 | Strong |

| Cultural appropriateness and metaphors | 0.6875 | 0.9375 | 0.875 | 1.00 | 0.875 | 0.88 ± 0.11 | Very high agreement |

| Illustration and layout quality | 0.5625 | 0.625 | 0.625 | 0.625 | 0.50 | 0.59 ± 0.05 | Acceptable |

| Flow and organisation | 0.50 | 0.5625 | 0.5625 | 0.5625 | 0.5625 | 0.55 ± 0.02 | Acceptable |

| Engagement and tone | 0.4375 | 0.6875 | 0.6875 | 0.6875 | 0.6875 | 0.64 ± 0.10 | Strong |

| Perceived feasibility and utility | 0.375 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.5625 | 0.5625 | 0.50 ± 0.07 | Acceptable perceived feasibility |

| Module | Key Concept | Urdu Metaphor |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Understanding Pain—Pain is protection, not damage | گھر بارش میں (House in Rain) |

| 2 | Mind–Body Connection—Fear and thoughts influence pain | چوکیدار زیادہ محتاط (Over-Protective Guard) |

| 3 | Motion Is Medicine—Gentle movement teaches safety | زنگ لگا دروازہ (Rusting Door) |

| 4 | Healthy Habits—Sleep, diet, and stress affect pain | توازن کی ترازو (Balance Scale) |

| 5 | Recovery and Hope—Brains can re-learn safety | روشنی کا سفر (Journey of Light) |

| 6 | Self-care—Supported by personal values/faith | ایمان اور عمل (Faith and Action) |

| 7 | Communication—Words as medicine in healing | الفاظ کا مرہم (Words as Medicine) |

| 8 | Family Support—Encouragement reduces fear | گھر کی طاقت (Strength of Family) |

| 9 | Movement Confidence—Gradual exposure builds trust | پگڈنڈی راستہ (Path to Confidence) |

| 10 | Relapse and Resilience—Flare-ups are learning, not failure | سفر جاری ہے (Journey Continues) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Khan, M.N.U.; Malhotra, A.; Cameron, M. Development, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of Urdu Pain Neuroscience Education Materials for Low Back Pain in Pakistan. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010054

Khan MNU, Malhotra A, Cameron M. Development, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of Urdu Pain Neuroscience Education Materials for Low Back Pain in Pakistan. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhan, Muhammad Naseeb Ullah, Aastha Malhotra, and Melainie Cameron. 2026. "Development, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of Urdu Pain Neuroscience Education Materials for Low Back Pain in Pakistan" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010054

APA StyleKhan, M. N. U., Malhotra, A., & Cameron, M. (2026). Development, Cultural Adaptation, and Content Validation of Urdu Pain Neuroscience Education Materials for Low Back Pain in Pakistan. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010054