Malformation Pattern and Molecular Findings in the FGFR1-Related Hartsfield Syndrome Phenotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

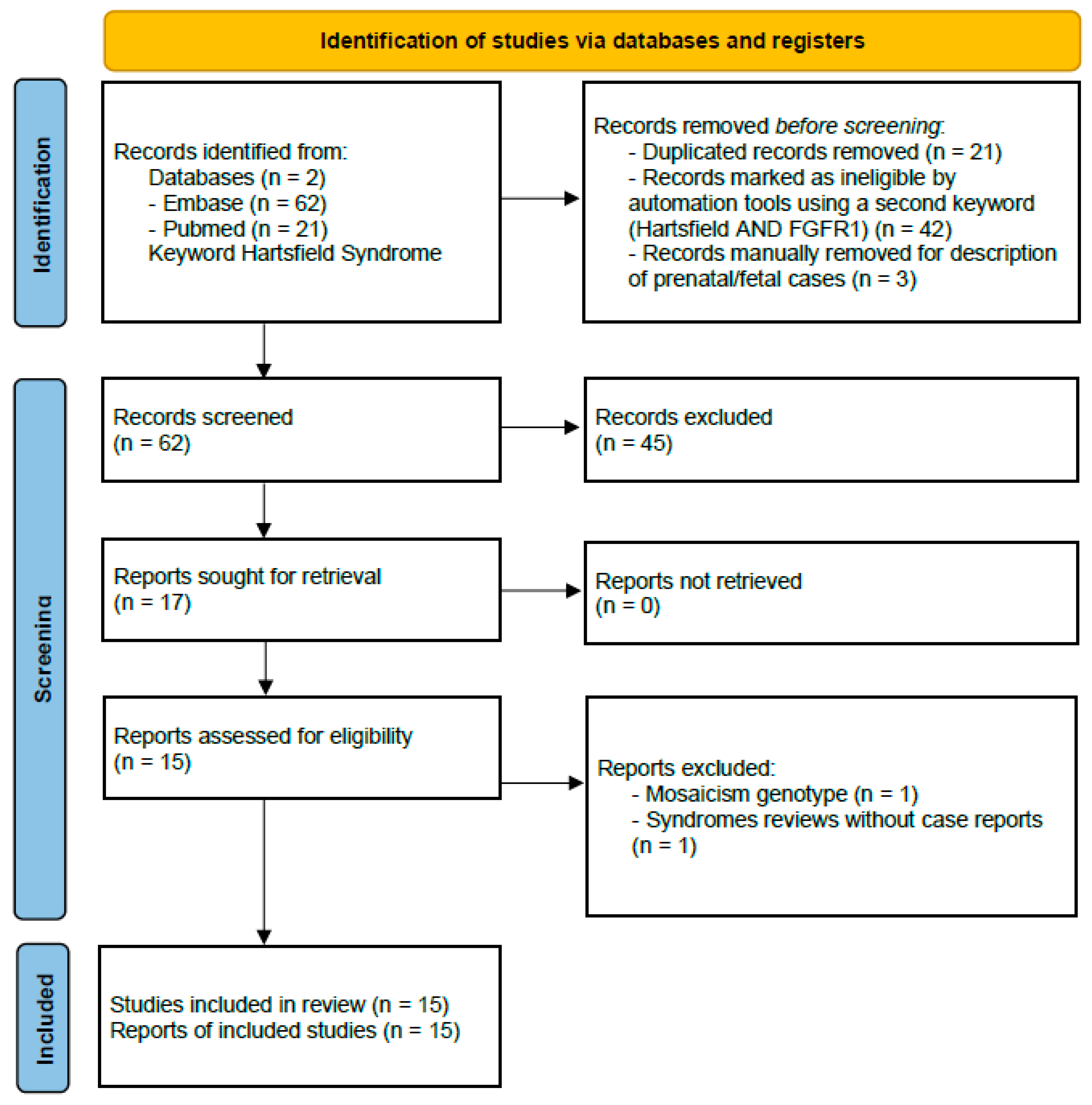

2. Relevant Sections

2.1. Frequent Anomalies: The Split-Hand/Foot Malformation (SHFM) Phenotype

2.2. Other Associated Congenital Disorders

- Craniofacial anomalies were present in all patients (100%) and included cleft lip/palate, auricular malformations (outer ear anomalies, low set, microtia/small/cupped, dysplastic and skin tag), microcephaly, hyper/hypotelorism, nose anomalies (depressed nasal bridge, nasal tip clefting), midface and malar hypoplasia, retrognathia, abnormal oral cavity and telecanthus. One patient showed unilateral aural atresia and auricular pit, and other two individuals showed, respectively, (1) oligodontia of the permanent dentition, retention of multiple primary teeth, amelogenesis imperfecta and single central incisor with multiple hypodontia and (2) deformities of teeth 8 and 9, class II malocclusion, class II molar occlusion and palatal fistula, and anterior and inferior premaxilla were identifiable in an additional subject. Other singularly reported anomalies were high forehead, abnormal cranial sutures (prominent metopic and coronal sutures, wide patent sagittal and lambdoid sutures and anterior and posterior fontanelles), macrocephaly, colpocephaly, missing columella and glioma.

- Some of the main craniofacial features of HRTFDS are shown in Figure 2.

- Holoprosencephaly (lobar or semilobar) was identified in 90%, while corpus callosum (CC) anomalies, mainly consisting of partial or anterior portions or complete agenesis, were identified in 88%.

- Anomalies of the genitourinary tract, comprising cryptorchidism, hypoplastic testes and micropenis/microphallus were diagnosed in 88%.

- Cardiovascular malformations were recognizable in 80% and comprised aortic coarctation and isthmus stenosis. A single patient displayed lumbosacral spine vascular malformation associated with coarctation of the aorta.

- Skeletal anomalies and radiological findings were identified 100%. These principally included metacarpal or metatarsal fusions, rays’ absence, bones hypoplasia, dysplasia and syndactyly. Peculiar congenital malformations comprised thumbs bifurcation, metatarsal inverted Y synostosis and hand bifid distal phalanges; hip dysplasia was also reported.

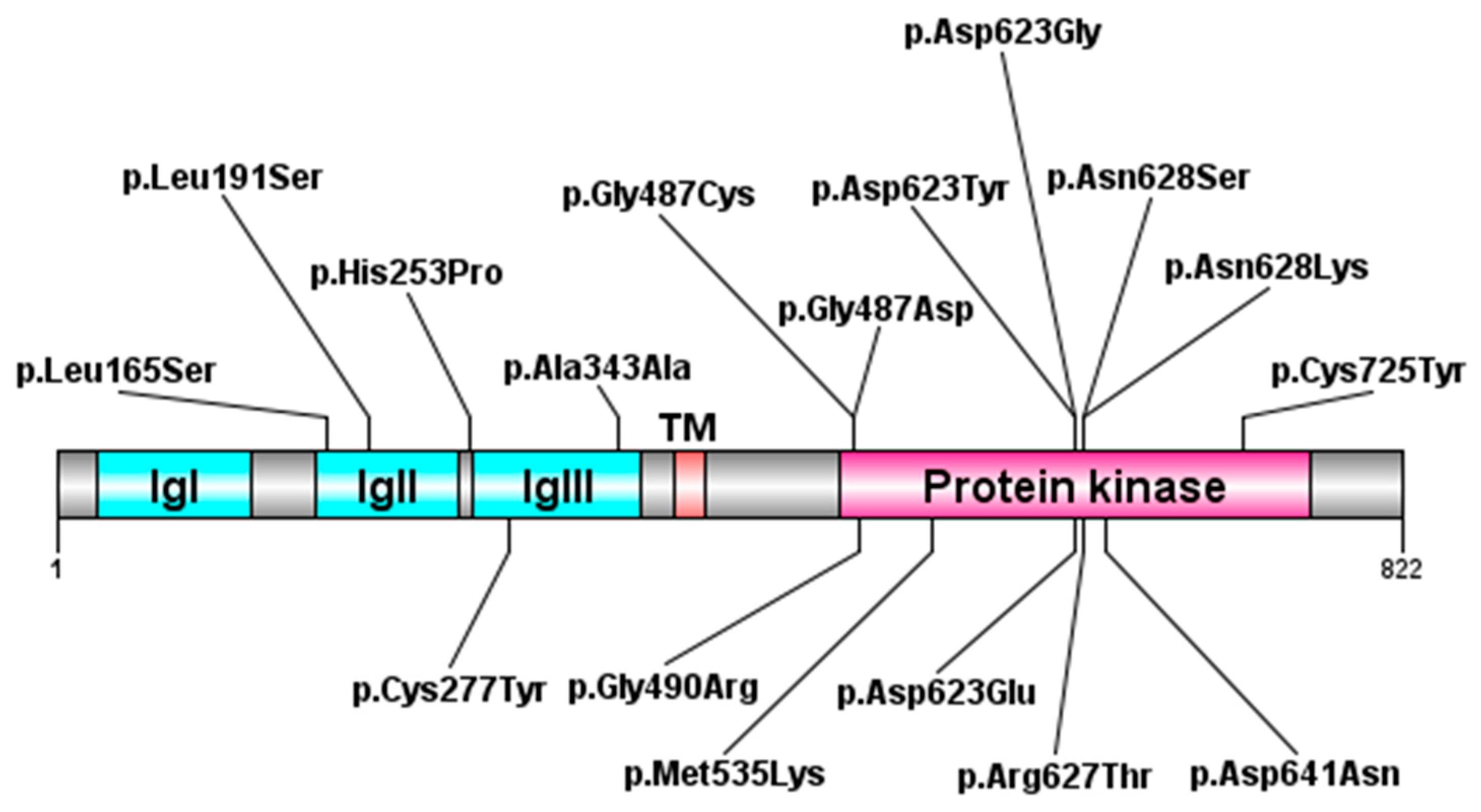

2.3. Molecular Aspects

2.4. Other Medical Issues and Global Clinical Management

- Genetics, for clinical and molecular diagnosis, family and proband reproductive risks, coordination of the other medical specialists and cooperation with them.

- Neuropsychiatric, ID/DD, spasticity, seizures, temperature dysregulation, sleep–wake cycles disturbance, psychiatric conditions (anxiety, aggressive or self-injurious behavior) and feeding problems. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to investigate HPE and other CNS anomalies as well as electroencephalography (EEG) is suggested in case of seizures.

- Endocrine, for the central endocrine disorders, which are associated with midline brain defects, impairing the pituitary. These include growth hormone deficiency, central diabetes insipidus and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

- Craniofacial, for cleft lip/palate and related feeding problems.

- Musculoskeletal, for SHFM and motor impairment.

- Cardiovascular, for congenital heart and vascular diseases. Echocardiogram exam should be considered among diagnostic investigations.

2.5. Malformation Phenotypes in Differential Diagnosis

- TP63-related disorders. This represents a wide group of genetic syndromes, which manifests with ectodermal dysplasia (hypohidrosis, nail dysplasia, sparse hair, tooth abnormalities), cleft lip/palate, SHFM/syndactyly. Other characteristics comprise lacrimal duct obstruction, hypopigmentation, hypoplastic breasts and/or nipples and hypospadias. The associated phenotypes are the Ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, cleft lip/palate syndrome 3 (EEC3; MIM#) [27], Acro-dermo-ungual-lacrimal-tooth (ADULT) syndrome (MIM#103285) [28], Limb-mammary syndrome (LMS, MIM#603543) [29] and Split-hand/foot malformation type 4 (SHFM4, MIM#605289) [30] and orofacial cleft 8 (OFC8, MIM#618149) [31]. The association of ankyloblepharon (tissue strands that completely or partially fuse the upper and lower eyelids), skin erosions especially on the scalp with areas of scarring, alopecia, trismus and excessive freckling describe the Ankyloblepharon-Ectodermal defects-Cleft lip/palate (AEC) syndrome or Hay–Wells syndrome (MIM#106260), comprising Rapp–Hodgkin syndrome (RHS, MIM#129400) [32].

- Genoa syndrome (MIM#601370), which is defined by semilobar holoprosencephaly, craniosynostosis and some skeletal anomalies such as small vertebral bodies, coxa valga and hypoplastic terminal phalanges of fingers [33]. Molecular bases are yet unknown.

- Duplication of the ANOS1 gene (ANOSMIN 1, MIM*300836), associated with the X-linked Kallmann 1 syndrome (KAL1, MIM#308700), which can cause a phenotype reminiscent HRTFDS and consisting of hyperosmia, ectrodactyly, genital anomalies and mild ID [34].

2.6. Genetic Counseling and Inheritance

- Autosomal dominant transmission.The condition is generally transmitted in an autosomal dominant fashion, and novel cases originate from a de novo mutational event, which can be confirmed by parental genetic testing. In the presence of a biologically confirmed paternal and maternal identity, the recurrence risk in these families is presumed to be low, and the chance to generate another individual with the condition depends on the presence of germinal (or somatic and germline) parental mosaicism, an event which has been previously described (Supplementary Table S1) [15,19,35].

- Autosomal recessive transmission.This model of inheritance has been observed (Supplementary Table S1) [6]. The reproductive risk will be 25% for two ascertained heterozygous carriers. If the pathogenic variant is identified in only one parent (and parental identity testing has confirmed biological maternity and paternity) and inherited by the son, the possible biological mechanisms leading to an affected individual could be (i) a de novo variant occurred in the wild-type allele in the index-case or (ii) a postzygotic de novo event in a mosaic parent [36]; (iii) uniparental isodisomy for the parental chromosome with the pathogenic variant could also be hypothesized.

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Present Review

- Small sample size effects on generalizability.

- Potential ascertainment bias in published case reports.

- Heterogeneity in clinical reporting across different centers.

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEC | Ankyloblepharon-Ectodermal Defects-Cleft lip/palate |

| ADULT | Acro-dermo-ungual-lacrimal-tooth |

| ANOS1 | Anosmin 1 |

| CC | Corpus callosum |

| CNS | Central Nervous System |

| CL/P | Cleft lip/palate |

| DD | Developmental delay |

| EEC3 | Ectrodactyly, ectodermal dysplasia, cleft lip/palate syndrome 3 |

| FGF | Fibroblast Growth Factor |

| FGFR1 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 |

| FGFRs | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptors |

| F2G | Face2Gene |

| HPE | Holoprosencephaly |

| HRTFDS | Hartsfield syndrome |

| H/F | Hands/feet |

| ID | Intellectual disability |

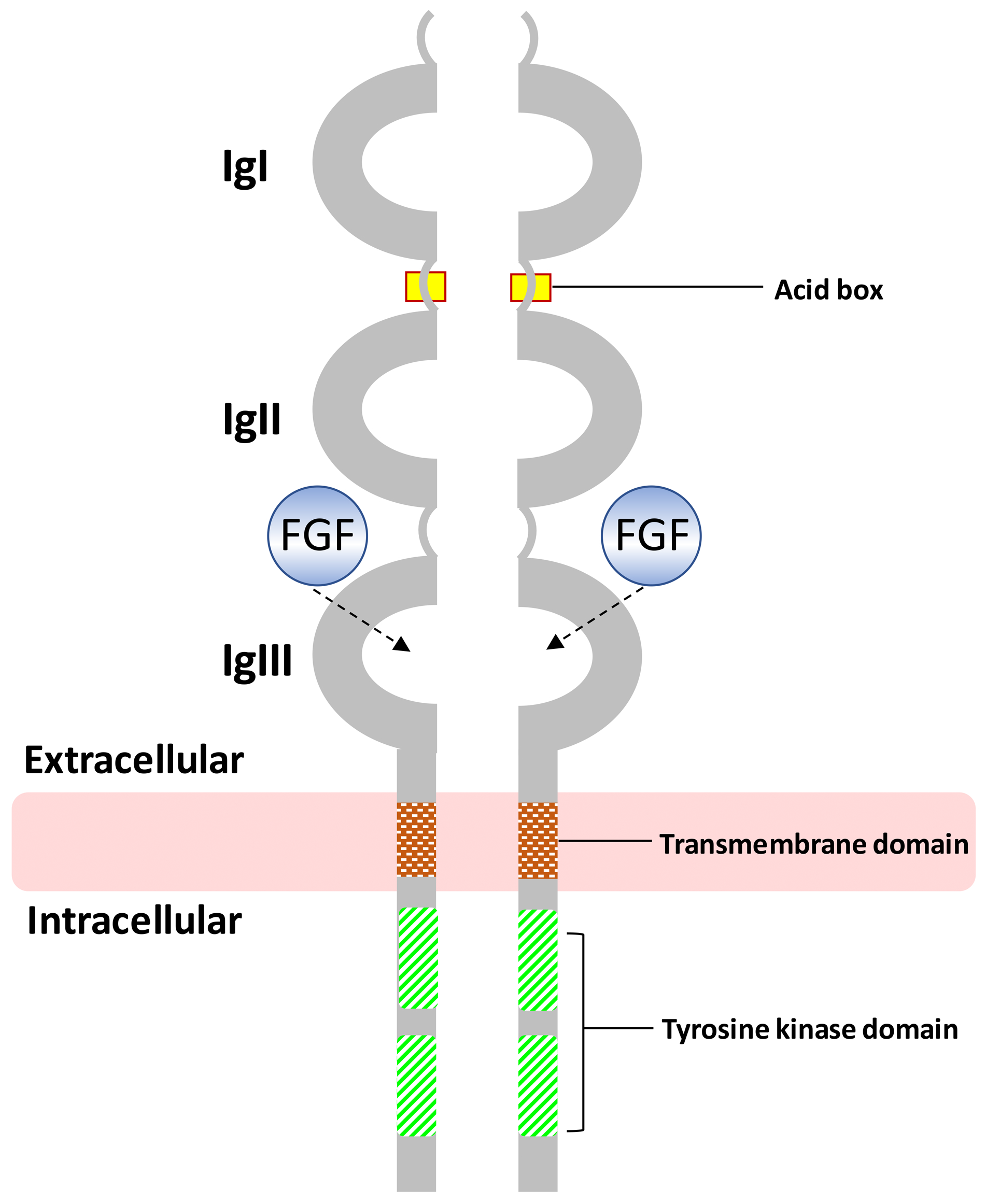

| IgI | Immunoglobulin-like I |

| IgII | Immunoglobulin-like II |

| IgIII | Immunoglobulin-like III |

| JWS | Jackson-Weiss syndrome |

| KAL1 | X-linked Kallmann 1 syndrome |

| KAL2 | Kalmann syndrome 2 |

| LMS | Limb-mammary syndrome |

| TRIGNO1 | Trigonocephaly 1 |

| OGD | Osteoglophonic dysplasia |

| OFC8 | Orofacial cleft 8 |

| RHS | Rapp-Hodgkin syndrome |

| SHFM | Split-hand/foot malformation |

| SHFM4 | Split-hand/foot malformation type 4 |

| TP63 | Tumor protein p63 |

| TK | Tyrosine kinase |

| TM | Transmembrane |

References

- Dodé, C.; Levilliers, J.; Dupont, J.M.; De Paepe, A.; Le Dû, N.; Soussi-Yanicostas, N.; Coimbra, R.S.; Delmaghani, S.; Compain-Nouaille, S.; Baverel, F.; et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat. Genet. 2003, 33, 463–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, W.; Petersen, B.; Collmann, H.; Grimm, T. An unusual FGFR1 mutation (fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 mutation) in a girl with non-syndromic trigonocephaly. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 2000, 91, 138–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, K.E.; Cabral, J.M.; Davis, S.I.; Fishburn, T.; Evans, W.E.; Ichikawa, S.; Fields, J.; Yu, X.; Shaw, N.J.; McLellan, N.J.; et al. Mutations that cause osteoglophonic dysplasia define novel roles for FGFR1 in bone elongation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005, 76, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muenke, M.; Schell, U.; Hehr, A.; Robin, N.H.; Losken, H.W.; Schinzel, A.; Pulleyn, L.J.; Rutland, P.; Reardon, W.; Malcolm, S.; et al. A common mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene in Pfeiffer syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabs, E.W.; Li, X.; Scott, A.F.; Meyers, G.; Chen, W.; Eccles, M.; Mao, J.I.; Charnas, L.R.; Jackson, C.E.; Jaye, M. Jackson-Weiss and Crouzon syndromes are allelic with mutations in fibroblast growth factor receptor 2. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 275–279, Erratum in Nat. Genet. 1995, 9, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonis, N.; Migeotte, I.; Lambert, N.; Perazzolo, C.; de Silva, D.C.; Dimitrov, B.; Heinrichs, C.; Janssens, S.; Kerr, B.; Mortier, G.; et al. FGFR1 mutations cause Hartsfield syndrome, the unique association of holoprosencephaly and ectrodactyly. J. Med. Genet. 2013, 50, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilain, C.; Mortier, G.; Van Vliet, G.; Dubourg, C.; Heinrichs, C.; de Silva, D.; Verloes, A.; Baumann, C. Hartsfield holoprosencephaly-ectrodactyly syndrome in five male patients: Further delineation and review. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 149A, 1476–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maldergem, L.; Gillerot, Y.; Vamos, E.; Toppet, M.; Watillon, P.; Van Vliet, G. Vasopressin and gonadotrophin deficiency in a boy with the ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-clefting syndrome. Acta Paediatr. 1992, 81, 365–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keaton, A.A.; Solomon, B.D.; van Essen, A.J.; Pfleghaar, K.M.; Slama, M.A.; Martin, J.A.; Muenke, M. Holoprosencephaly and ectrodactyly: Report of three new patients and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2010, 154C, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwalley Kalil, K.A.; Fargalley, H.S. Holoprosencephaly in an Egyptian baby with ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft syndrome: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2012, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takenouchi, T.; Okuno, H.; Kosaki, R.; Ariyasu, D.; Torii, C.; Momoshima, S.; Harada, N.; Yoshihashi, H.; Takahashi, T.; Awazu, M.; et al. Microduplication of Xq24 and Hartsfield syndrome with holoprosencephaly, ectrodactyly, and clefting. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2012, 158A, 2537–2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, R.; Brewer, C.; Burren, C.P. Hartsfield syndrome associated with a novel heterozygous missense mutation in FGFR1 and incorporating tumoral calcinosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 170A, 2222–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, M.; Miyoshi, T.; Nagashima, Y.; Shibata, N.; Yagi, H.; Fukuzawa, R.; Hasegawa, T. Novel heterozygous mutation in the extracellular domain of FGFR1 associated with Hartsfield syndrome. Hum. Genome Var. 2016, 3, 16034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansdon, L.A.; Bernabe, H.V.; Nidey, N.; Standley, J.; Schnieders, M.J.; Murray, J.C. The Use of Variant Maps to Explore Domain-Specific Mutations of FGFR1. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 1339–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhamija, R.; Kirmani, S.; Wang, X.; Ferber, M.J.; Wieben, E.D.; Lazaridis, K.N.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D. Novel de novo heterozygous FGFR1 mutation in two siblings with Hartsfield syndrome: A case of gonadal mosaicism. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2014, 164A, 2356–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, J.D.; Menapace, D.C.; Cofer, S.A. Otorhinolaryngologic manifestations of Hartsfield syndrome: Case series and review of literature. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2017, 98, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Hu, P.; Marino, J.; Hufnagel, S.B.; Hopkin, R.J.; Toromanović, A.; Richieri-Costa, A.; Ribeiro-Bicudo, L.A.; Kruszka, P.; Roessler, E.; et al. Dominant-negative kinase domain mutations in FGFR1 can explain the clinical severity of Hartsfield syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2016, 25, 1912–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palumbo, P.; Petracca, A.; Maggi, R.; Biagini, T.; Nardella, G.; Sacco, M.C.; Di Schiavi, E.; Carella, M.; Micale, L.; Castori, M. A novel dominant-negative FGFR1 variant causes Hartsfield syndrome by deregulating RAS/ERK1/2 pathway. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2019, 27, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courage, C.; Jackson, C.B.; Owczarek-Lipska, M.; Jamsheer, A.; Sowińska-Seidler, A.; Piotrowicz, M.; Jakubowski, L.; Dallèves, F.; Riesch, E.; Neidhardt, J.; et al. Novel synonymous and missense variants in FGFR1 causing Hartsfield syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2019, 179, 2447–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.; Tanigawa, J.; Kondo, H.; Nabatame, S.; Maruoka, A.; Sho, H.; Tanikawa, K.; Inui, R.; Otsuki, M.; Shimomura, I.; et al. Endocrinological Features of Hartsfield Syndrome in an Adult Patient with a Novel Mutation of FGFR1. J. Endocr. Soc. 2020, 4, bvaa041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szoszkiewicz, A.; Sowinska-Seidler, A.; Gruca-Stryjak, K.; Jamsheer, A. Intrafamilial Phenotypic Variability of the FGFR1 p.Cys277Tyr Variant: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. Genes 2025, 16, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tole, S.; Gutin, G.; Bhatnagar, L.; Remedios, R.; Hébert, J.M. Development of midline cell types and commissural axon tracts requires Fgfr1 in the cerebrum. Dev. Biol. 2006, 289, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mason, I. Initiation to end point: The multiple roles of fibroblast growth factors in neural development. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, C.; Bastos, M.; Pignatelli, D.; Borges, T.; Aragüés, J.M.; Fonseca, F. Novel FGFR1 mutations in Kallmann syndrome and normosmic idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: Evidence for the involvement of an alternatively spliced isoform. Fertil. Steril. 2015, 104, 1261–1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groth, C.; Lardelli, M. The structure and function of vertebrate fibroblast growth factor receptor 1. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2002, 46, 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, J.F.; Soriano, P. Diverse Fgfr1 signaling pathways and endocytic trafficking regulate mesoderm development. Genes. Dev. 2024, 38, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celli, J.; Duijf, P.; Hamel, B.C.J.; Bamshad, M.; Kramer, B.; Smits, A.P.T.; Newbury-Ecob, R.; Hennekam, R.C.; Van Buggenhout, G.; van Haeringen, A.; et al. Heterozygous germline mutations in the p53 homolog p63 are the cause of EEC syndrome. Cell 1999, 99, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiel, J.; Bougeard, G.; Francannet, C.; Raclin, V.; Munnich, A.; Lyonnet, S.; Frebourg, T. TP63 gene mutation in ADULT syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 9, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Bokhoven, H.; Hamel, B.C.; Bamshad, M.; Sangiorgi, E.; Gurrieri, F.; Duijf, P.H.; Vanmolkot, K.R.; van Beusekom, E.; van Beersum, S.E.; Celli, J.; et al. p63 gene mutations in EEC syndrome, limb-mammary syndrome, and isolated split hand-foot malformation suggest a genotype-phenotype correlation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001, 69, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianakiev, P.; Kilpatrick, M.W.; Toudjarska, I.; Basel, D.; Beighton, P.; Tsipouras, P. Split-hand/split-foot malformation is caused by mutations in the p63 gene on 3q27. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000, 67, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leoyklang, P.; Siriwan, P.; Shotelersuk, V. A mutation of the p63 gene in non-syndromic cleft lip. J. Med. Genet. 2006, 43, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.A.; Duijf, P.H.G.; Doetsch, V.; Irvine, A.D.; de Waal, R.; Vanmolkot, K.R.J. Hay-Wells syndrome is caused by heterozygous missense mutations in the SAM domain of p63. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2001, 10, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camera, G.; Lituania, M.; Cohen, M.M., Jr. Holoprosencephaly and primary craniosynostosis: The Genoa syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1993, 47, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sowińska-Seidler, A.; Piwecka, M.; Olech, E.; Socha, M.; Latos-Bieleńska, A.; Jamsheer, A. Hyperosmia, ectrodactyly, mild intellectual disability, and other defects in a male patient with an X-linked partial microduplication and overexpression of the KAL1 gene. J. Appl. Genet. 2015, 56, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Dhamija, R.; Wren, C.; Wang, X.; Babovic-Vuksanovic, D.; Spector, E. Detection of gonadal mosaicism in Hartsfield syndrome by next generation sequencing. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2016, 170, 3359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jónsson, H.; Sulem, P.; Kehr, B.; Kristmundsdottir, S.; Zink, F.; Hjartarson, E.; Hardarson, M.T.; Hjorleifsson, K.E.; Eggertsson, H.P.; Gudjonsson, S.A.; et al. Parental influence on human germline de novo mutations in 1548 trios from Iceland. Nature 2017, 549, 519–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Schweitzer, R.; Sun, D.; Kaghad, M.; Walker, N.; Bronson, R.T.; Tabin, C.; Sharpe, A.; Caput, D.; Crum, C.; et al. p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 1999, 398, 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| System/Concern | Features | Frequencies (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Craniofacial | Abnormal outer ear | 87% |

| Oral cleft | 76% | |

| Limb | Radiologically identified skeletal defects | 100% |

| Split-hand/foot malformation | 92% | |

| Genitourinary | Penis/testes anomalies | 100% |

| Central Nervous System (CNS) | Holoprosencephaly | 90% |

| Cardiovascular | Aortic malformation | 80% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gaudioso, F.; Pascolini, G. Malformation Pattern and Molecular Findings in the FGFR1-Related Hartsfield Syndrome Phenotype. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010004

Gaudioso F, Pascolini G. Malformation Pattern and Molecular Findings in the FGFR1-Related Hartsfield Syndrome Phenotype. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleGaudioso, Federica, and Giulia Pascolini. 2026. "Malformation Pattern and Molecular Findings in the FGFR1-Related Hartsfield Syndrome Phenotype" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010004

APA StyleGaudioso, F., & Pascolini, G. (2026). Malformation Pattern and Molecular Findings in the FGFR1-Related Hartsfield Syndrome Phenotype. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010004