Adverse Drug Reaction to Linezolid in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

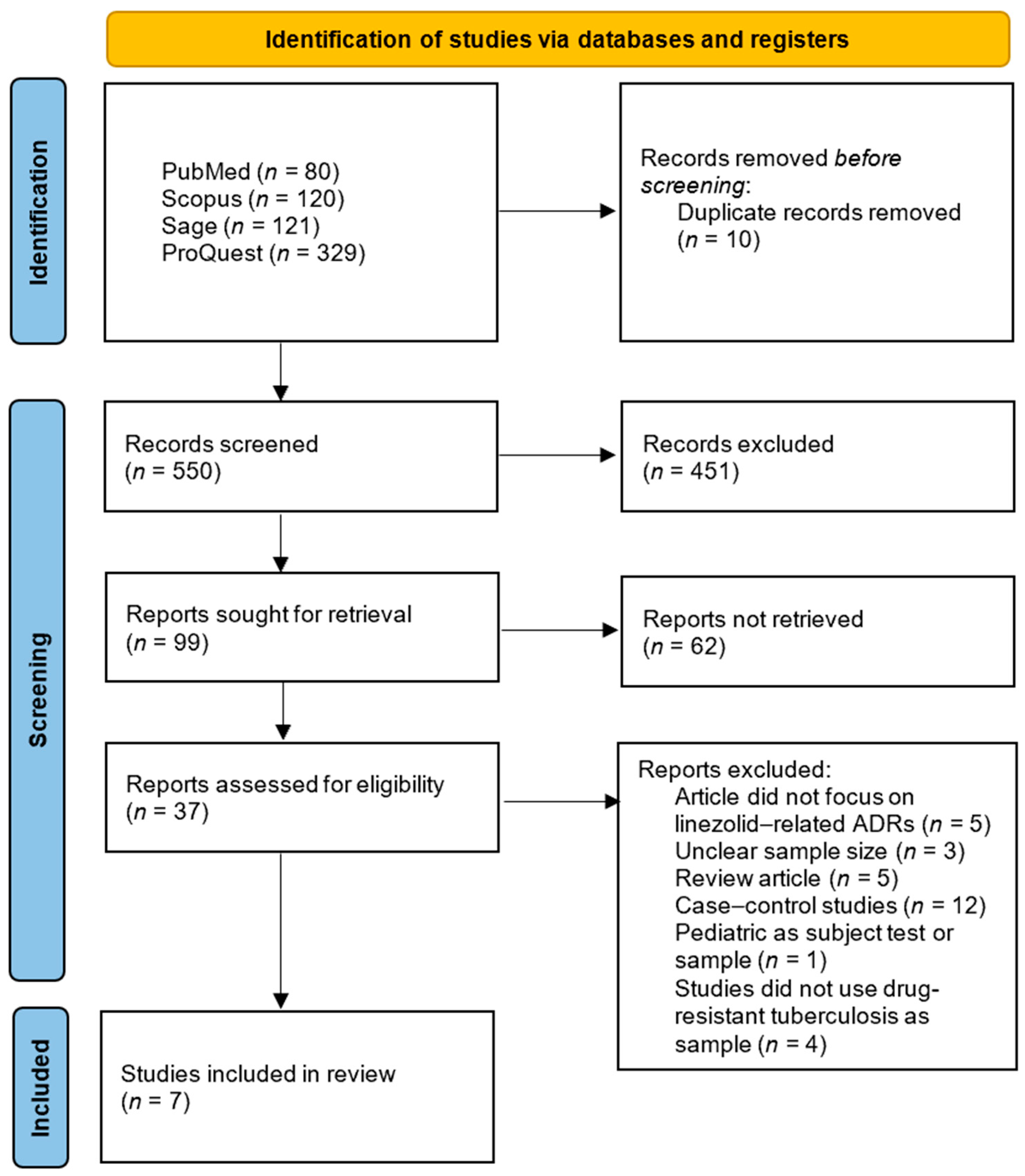

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Literature Source

2.3. Eligibility Criteria and Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

3.2. Study Characteristics

| JBI Appraisal Questions and the Value | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | Appraisal Result |

| Park et al., 2006 [22] | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | Included |

| Xu et al., 2012 [20] | - | - | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | - | √ | Included |

| Migliori et al., 2009 [23] | √ | √ | √ | - | - | √ | √ | - | × | √ | √ | Included |

| Koh et al., 2009 [24] | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | × | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | Included |

| Wasserman et al., 2022 [12] | - | - | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Included |

| Imperial et al., 2022 [25] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Included |

| Padmapriyadarsini et al., 2023 [18] | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | × | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | Included |

| Author, Year | Study Location/Study Design | Sample Size | Dose of Linezolid in Study | Previous History TB (Yes/No/N/A) | Hematologic Toxicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Time of Occurrence | Linezolid Adjustment | Linezolid Discontinuation | Symptomatic Therapy | |||||

| Park et al., 2006 [22] | South Korea/Prospective cohort | Total: 8 patients all MDR-TB | 2 patients: 600 mg once daily 5 patients: 600 mg twice daily for 2 weeks 1 patient: 600 mg twice daily for 7 weeks | NA | Total: 1 incident Anemia (Hb 9.6 mg/dL): 1 patient (600 mg twice daily) | After 7 weeks | 600 mg once daily | - | - |

| Xu et al., 2012 [20] | China/Retrospective cohort | Total 18 patients. 15 patients with XDR-TB and 3 patients with MDR-TB | 1. 1200 mg once daily IV drip infusion at treatment initiation for all patients. 2. 3 patients adjusted for body weight for 900 mg once daily | Yes: All patients | Total: 13 incidents Anemia: 2 incidents (900 mg once daily), 10 incidents (1200 mg once daily) Mild to moderate thrombocytopenia (Platelet 50–109 × 109/L): 3 incidents (1200 mg once daily) Leucopenia (<4.0 × 109/L): 7 incidents (1200 mg once daily) | Anemia: 2 incidents (900 mg once daily) occurred after 19 days 10 incidents (1200 mg once daily) occurred after 80.1 days Mild to moderate thrombocytopenia (Platelet 50–109 × 109/L): 3 incidents (1200 mg once daily) Leucopenia (<4.0 × 109/L): 7 incidents (1200 mg once daily) | Anemia: 2 incidents (900 mg once daily) adjusted to 600 mg once daily 10 incidents (1200 mg once daily): 8 incidents adjusted to 600 mg once daily, 3 incidents adjusted to 900 mg once daily, and 1 incident adjusted to 300 mg once daily Leucopenia: 5 incidents (1200 mg once daily) adjusted to 600 mg once daily 2 incidents adjusted to 900 mg once daily Thrombocytopenia: 2 incidents (1200 mg once daily) adjusted to 600 mg once daily 1 incident adjusted to 900 mg once daily | 7 incidents managed by combination of erythropoietin, blood transfusion, folic acid, and iron supplementation. | |

| Migliori et al., 2009 [23] | Germany/Retrospective cohort | Total 195 MDR/XDR-TB. 85 treated with linezolid 110 without linezolid. From 85 with linezolid, 75 patients MDR-TB and 10 patients with XDR-TB. | 1. 28 patients: 600 mg once daily 2. 57 patients: 600 mg twice daily | N/A | Total: 30 incidents Anemia: 3 incidents (600 mg once daily), 20 incidents (600 mg twice daily) Thrombocytopenia: 7 incidents (600 mg twice daily) | 69 days | Yes | Yes | Yes (5 requiring blood transfusion) |

| Koh et al., 2009 [24] | South Korea/Retrospective cohort | Total 24 patients all MDR-TB | 300 mg once daily: 17 patients 600 mg once daily: 7 patients | N/A | Total: 1 incident Leucopenia: 1 incident (600 mg once daily) | 104 days (600 mg once daily) | Adjusted to 300 mg once daily after temporarily discontinuation | ||

| Wasserman et al., 2022 [12] | South Africa/Prospective cohort | Total 151 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg once daily: 148 patients 300 mg once daily: 3 patients | Yes: 111 patients from 151 patients | Total: 74 incidents Anemia: 58 incidents Grade 1: 24 Grade 2: 14 Grade 3: 13 Grade 4: 6 Thrombocytopenia: 10 incidents Grade 1: 8 Grade 2: 2 Leukopenia: 6 incidents Grade 1: 5 Grade 3: 1 | Anemia: 77 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Imperial et al., 2022 [25] | South Africa/Retrospective cohort | Total 109 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg twice daily or 1200 mg once daily | N/A | Total: 44 incidents Anemia: 38 incidents Thrombocytopenia: 6 incidents | 56 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Padmapriyadarsini et al., 2023 [18] | India/Prospective cohort | Total 165 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg once daily | N/A | Anemia: 78 incidents | 56 days | Yes, 600 mg to 300 mg once daily | - | Yes, with hematinic support. One patient received blood transfusion. |

| Author, Year | Study Location/Study Design | Sample Size | Dose of Linezolid in Study | Previous History TB (Yes/No/N/A) | Polyneuropathy Toxicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amount | Time of Occurrence | Linezolid Adjustment | Linezolid Discontinuation | Symptomatic Therapy | |||||

| Park et al., 2006 [22] | South Korea/Prospective cohort | Total: 8 patients all MDR-TB | 1. 2 patients: 600 mg once daily 2. 5 patients: 600 mg twice daily for 2 weeks 3. 1 patient: 600 mg twice daily for 7 weeks | N/A | Peripheral neuropathy: Total: 4 incidents (600 mg twice daily) Optic neuropathy: 2 incidents (600 mg twice daily) | Peripheral neuropathy: 120–330 days Optic neuropathy: 240–270 days | Peripheral neuropathy: 600 mg once daily then symptomatic therapy (Amitriptyline, gabapentin, vitamin B6) | Optic neuropathy: Linezolid discontinued | Amitriptyline, gabapentin, vitamin B6 |

| Xu et al., 2012 [20] | China/Retrospective cohort | Total 18 patients. 15 patients with XDR-TB and 3 patients with MDR-TB | 1. 1200 mg once daily IV drip infusion at treatment initiation for all patients. 2. 3 patients adjusted for body weight for 900 mg once daily | Yes: All patients | Peripheral neuropathy: Total: 11 incidents 9 incidents (1200 mg once daily) 1 incident (900 mg once daily) Optic neuropathy: Total: 3 incidents 1 incident (900 mg once daily) 2 incidents (1200 mg once daily) | Peripheral neuropathy: 9 incidents (1200 mg once daily) occurred after 90.8 days 1 incident (900 mg once daily) occurred after 7 days Optic neuropathy: 1 incident (900 mg once daily) occurred after 7 days 2 incidents (1200 mg once daily) occurred after 47.5 days | Peripheral neuropathy: 7 incidents adjusted to 600 mg once daily 1 incident adjusted to 900 mg once daily 1 incident adjusted to 300 mg once daily Symptomatic therapy: Vitamin B6, and B12 Optic neuropathy: 600 mg once daily. 1 incident stop cause of worsening. Symptomatic therapy: Vitamin B12 | Optic neuropathy: After linezolid adjusted to 600 mg once daily and symptomatic therapy, 1 incident discontinued of linezolid cause of worsening. | |

| Migliori et al., 2009 [23] | Germany/Retrospective cohort | Total 195 MDR/XDR-TB. 85 treated with linezolid 110 without linezolid. From 85 with linezolid, 75 patients MDR-TB and 10 patients with XDR-TB. | 1. 28 patients: 600 mg once daily 2. 57 patients: 600 mg twice daily | N/A | Total: 3 incidents Polyneuropathy: 1 incident (600 mg once daily), 2 incidents (600 mg twice daily) | 69 days | N/A | Discontinued on some cases | |

| Koh et al., 2009 [24] | South Korea/Retrospective cohort | Total 24 patients all MDR-TB | 300 mg once daily: 17 patients 600 mg once daily: 7 patients | N/A | Total: 8 incidents Peripheral neuropathy: 4 incidents (300 mg once daily) 4 incidents (600 mg once daily) | 289 days (300 mg once daily) 104 days (600 mg once daily) | 4 incidents (600 mg once daily) adjusted to 300 mg once daily | 1 incident (300 mg once daily) discontinued | |

| Wasserman et al., 2022 [12] | South Africa/Prospective cohort | Total 151 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg once daily: 148 patients 300 mg once daily: 3 patients | Yes: 111 patients from 151 patients | Total: 54 incidents Peripheral neuropathy: 37 incidents Grade 1: 32 incidents Grade 2: 4 incidents Grade 3: 0 Grade 4: 1 incident Optic neuropathy: 17 incidents | Peripheral neuropathy: 70 days Optic neuropathy: 70 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Imperial et al., 2022 [25] | South Africa/Retrospective cohort | Total 109 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg twice daily or 1200 mg once daily | N/A | Peripheral neuropathy: 80 incidents | 98 days | Yes | Yes | |

| Padmapriyadarsini et al., 2023 [18] | India/Prospective cohort | Total 165 patients all MDR-TB | 600 mg once daily | N/A | Total: 71 incidents Peripheral neuropathy: 69 incidents Optic Neuropathy: 2 incidents | Peripheral neuropathy: 112 days Optic Neuropathy: 60 days | - | - | Yes |

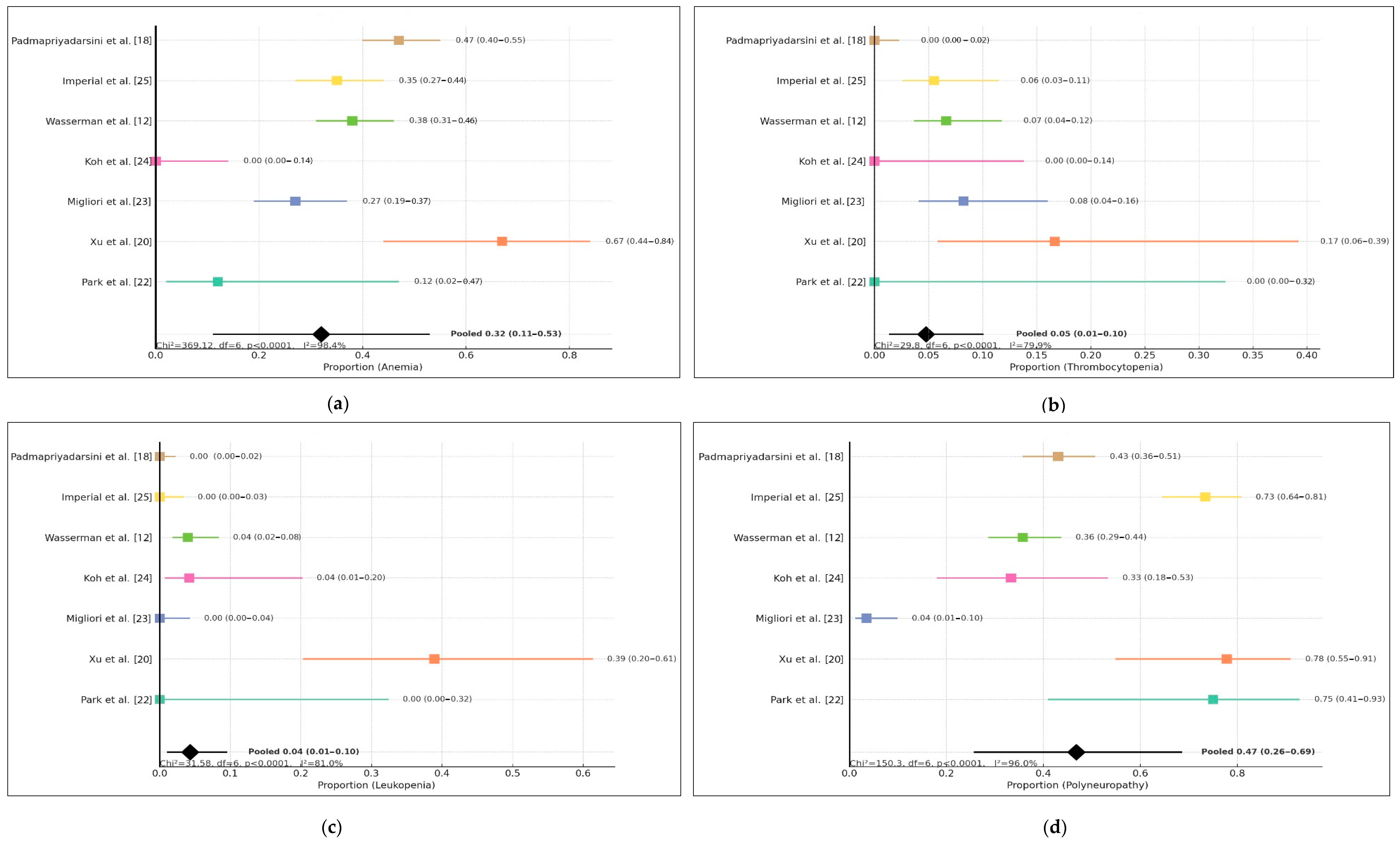

3.3. Profile of Linezolid-Related Adverse Events

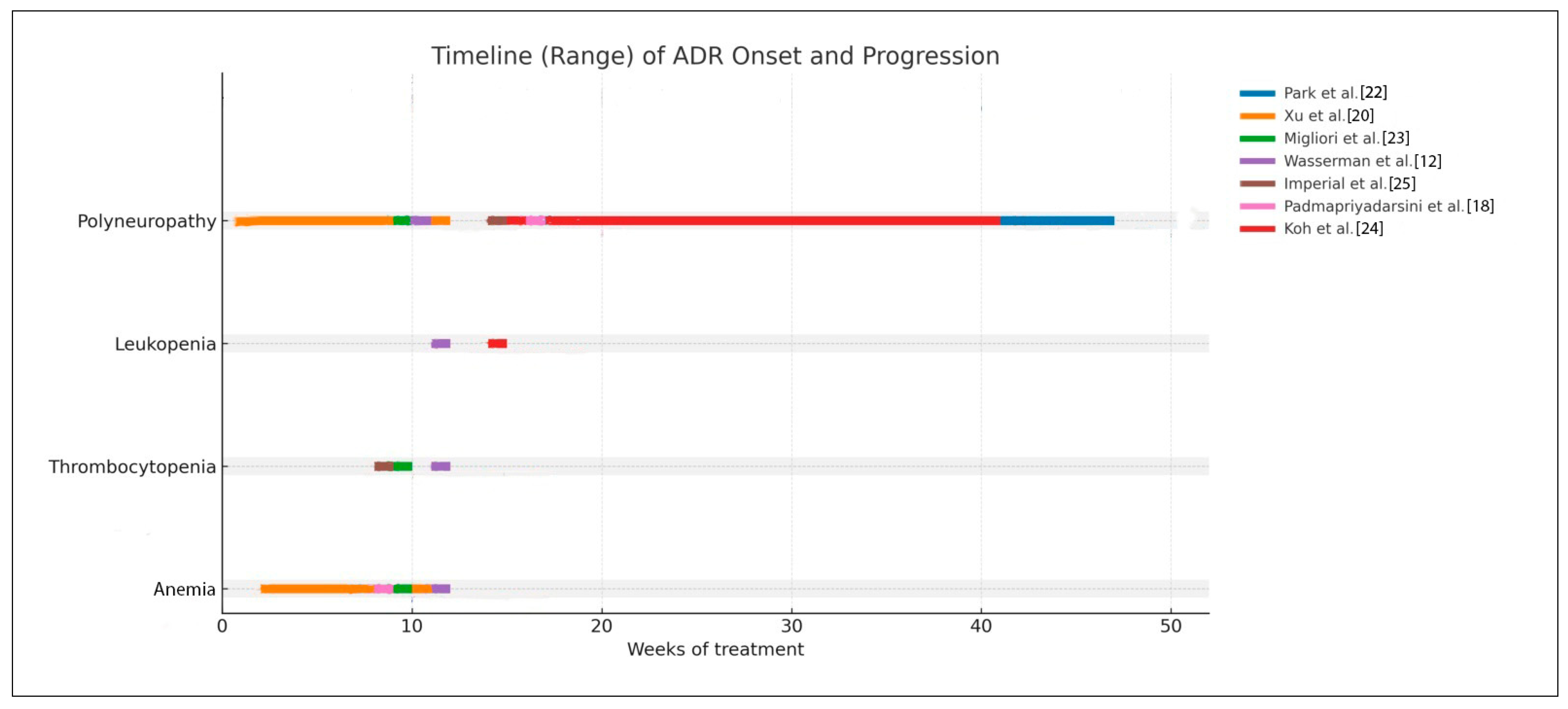

3.4. Time-Dependent Hematologic and Polyneuropathy Events of Linezolid

4. Discussion

4.1. Hematologic Toxicity

4.2. Peripheral Neuropathy

4.3. Optic Neuropathy

4.4. Another Type of Linezolid-Related ADRs

4.5. Clinical Implication, Practical ADR Management, and Monitoring Risk

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NR | Not reported |

| N/A | Not applicable |

| MDR-TB | Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis |

| XDR-TB | Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis |

| ADRs | Adverse drug reactions |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| RCT | Randomized controlled trials |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

References

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Health, Indonesia. Dashboard of Tuberculosis in Indonesia; Jakarta, Indonesia. 2025. Available online: https://www.tbindonesia.or.id/pustaka-tbc/data-kondisi-tbc/ (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- World Health Organization. WHO Operational Handbook on Tuberculosis: Module 4: Treatment and Care; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dayyab, F.; Iliyasu, G.; Ahmad, B.; Habib, A. Early safety and efficacy of linezolid-based combination therapy among patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis in North-western Nigeria. Int. J. Mycobacteriology 2021, 10, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Yao, L.; Hao, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Liu, X.; Wu, M.; Zen, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of linezolid for the treatment of XDR-TB: A study in China. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diacon, A.H.; Jager, V.R.D.; Dawson, R.; Narunsky, K.; Vanker, N.; Burger, D.A.; Everitt, D.; Pappas, F.; Nedelman, J.; Mendel, C.M. Fourteen-Day Bactericidal Activity, Safety, and Pharmacokinetics of Linezolid in Adults with Drug-Sensitive Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e02012-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, L.-P.; Zhang, Q.; Lou, H.; Shen, X.-N.; Qu, Q.-R.; Cao, J.; Wei, W.; Sha, W.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, L.-P.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of regimens containing linezolid for treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary Disease. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2023, 22, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.U.; Khan, A.; Khan, F.U.; Hayat, K.; Rehman, A.u.; Chang, J.; Khalid, W.; Noor, S.; Khan, A.; Fang, Y. Assessment of Adverse Drug Events, Their Risk Factors, and Management Among Patients Treated for Multidrug-Resistant TB: A Prospective Cohort Study From Pakistan. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 876955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Xiao, K.; Yan, P.; Fang, X.; Xie, L. Nomogram prediction model called “ADPLCP” for predicting linezolid-associated thrombocytopenia in elderly individuals. J. Intensive Med. 2023, 3, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, A.; Dong, M.; Cheng, J.; Liao, X.; Dong, W.; Liu, C.; Hu, C.; Yang, J.; Kang, Y. Clinical efficacy and safety of linezolid in intensive care unit patients. J. Intensive Med. 2023, 3, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehadian, A.; Santoso, P.; Menzies, D.; Ruslami, R. Anemia with elevation of growth differentiation factor-15 level in linezolid treated multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: Case series of three patients. IDCases 2022, 29, e01591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasserman, S.; Brust, J.C.M.M.; Abdelwahab, M.T.; Little, F.; Denti, P.; Wiesner, L.; Gandhi, N.R.; Meintjes, G.; Maartens, G. Linezolid toxicity in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: A prospective cohort study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 1146–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaspard, M.; Butel, N.; Helali, N.E.; Marigot-Outtandy, D.; Guillot, H.; Peytavin, G.; Veziris, N.; Bodaghi, B.; Flandre, P.; Petitjean, G.; et al. Linezolid-Associated Neurologic Adverse Events in Patients with Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis, France. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 1792–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letswee, G.; Kamau, H.; Gaida, R.; Truter, I. Haematological adverse effects associated with linezolid in patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis: An exploratory study. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 27, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, Q.; Xu, Y.; Lin, L.; Lang, Y.; Guo, S.; Zhang, R.; Cai, X. Mechanism underlying linezolid-induced peripheral neuropathy in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 946058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bano, S.; Nawaz, A.; Numan, A.; Hassan, M.A.; Shafique, M.B.A. A Case Report and Literature Review of the Outcome of Linezolid-Induced Optic and Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients with Multidrug-Resistant Pulmonary TB. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 908584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, A.; Shah, S.; Mistry, Y.; Chaturvedi, N.; Jariwala, D. Ocular side effects in tuberculosis patients receiving direct observed therapy containing ethambutol. Natl. J. Physiol. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 127–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padmapriyadarsini, C.; Solanki, R.; Jeyakumar, S.M.; Bhatnagar, A.; Muthuvijaylaksmi, M.; Jeyadeepa, B.; Reddy, D.; Shah, P.; Sridhar, R.; Vohra, V.; et al. Linezolid Pharmacokinetics and Its Association with Adverse Drug Reactions in Patients with Drug-Resistant Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.B.; Jiang, R.H.; Li, L.; Xiao, H.P. Linezolid in the treatment of MDR-TB: A retrospective clinical study. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2012, 16, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padmapriyadarsini, C.; Vohra, V.; Bhatnagar, A.; Solanki, R.; Sridhar, R.; Anande, L.; Muthuvijaylakshmi, M.; Bhatia, M.; Jeyadeepa, B.; Taneja, G.; et al. Bedaquiline, Delamanid, Linezolid and Clofazimine for Treatment of Pre-extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 76, 938–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, I.-N.; Hong, S.-B.; Oh, Y.-M.; Kim, M.-N.; Lim, C.-M.; Lee, S.D.; Koh, Y.; Kim, W.S.; Kim, D.S.; Kim, W.D.; et al. Efficacy and tolerability of daily-half dose linezolid in patients with intractable multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006, 58, 701–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliori, G.B.; Eker, B.; Richardson, M.D.; Sotgiu, G.; Zellweger, J.-P.; Skrahina, A.; Ortmann, J.; Girardi, E.; Hoffmann, H.; Besozzi, G.; et al. A retrospective TBNET assessment of linezolid safety, tolerability and efficacy in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Eur. Respir. J. 2009, 34, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, W.-J.; Kwon, O.J.; Gwak, H.; Chung, J.W.; Cho, S.-N.; Kim, W.S.; Shim, T.S. Daily 300 mg dose of linezolid for the treatment of intractable multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2009, 64, 388–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imperial, M.Z.; Nedelman, J.R.; Conradie, F.; Savic, R.M. Proposed Linezolid Dosing Strategies to Minimize Adverse Events for Treatment of Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 74, 1736–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.H.; Wu, V.C.; Tsai, I.J.; Ho, Y.L.; Hwang, J.J.; Tsau, Y.K.; Wu, C.Y.; Wu, K.D.; Hsueh, P.R. High frequency of linezolid-associated thrombocytopenia among patients with renal insufficiency. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2006, 28, 345–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, K.; Takeshita, A.; Ikawa, K.; Shigemi, A.; Yaji, K.; Shimodozono, Y.; Morikawa, N.; Takeda, Y.; Yamada, K. Higher linezolid exposure and higher frequency of thrombocytopenia in patients with renal dysfunction. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2010, 36, 179–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millard, J.; Pertinez, H.; Bonnett, L.; Hodel, E.M.; Dartois, V.; Johnson, J.L.; Caws, M.; Tiberi, S.; Bolhuis, M.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; et al. Linezolid pharmacokinetics in MDR-TB: A systematic review, meta-analysis and Monte Carlo simulation. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1755–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.N.; Wu, C.C.; Kuo, C.H.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, J.T.; Lin, Y.T.; Jhang, R.S.; Lin, S.W. Impact of high plasma concentrations of linezolid in Taiwanese adult patients—Therapeutic drug monitoring in improving adverse drug reactions. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2021, 120, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attassi, K.; Hershberger, E.; Alam, R.; Zervos, M.J. Thrombocytopenia Associated with Linezolid Therapy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2002, 34, 695–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeman, A.A.; Ofori-Asenso, R.; Agyeman, A.A.; Ofori-Asenso, R. Efficacy and safety profile of linezolid in the treatment of multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2016, 15, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Jiang, S.; Chen, X.; Han, L.; Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; Zhang, X. Analysis of the risk factors of linezolid-related haematological toxicity in Chinese patients. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2021, 46, 807–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerson, S.L.; Kaplan, S.L.; Bruss, J.B.; Le, V.; Arellano, F.M.; Hafkin, B.; Kuter, D.J. Hematologic Effects of Linezolid: Summary of Clinical Experience. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2723–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-S.; Lee, E.; Cho, Y.-J.; Lee, Y.J.; Rhie, S.J. Linezolid-induced thrombocytopenia increases mortality risk in intensive care unit patients, a 10 year retrospective study. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2019, 44, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Orlando, G.; Cozzi, V.; Cordier, L.; Baldelli, S.; Merli, S.; Fucile, S.; Gulisano, C.; Rizzardini, G.; Clementi, E. Linezolid plasma concentrations and occurrence of drug-related haematological toxicity in patients with gram-positive infections. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 586–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishijo, N.; Tsuji, Y.; Matsunaga, K.; Kutsukake, M.; Okazaki, F.; Fukumori, S.; Kasai, H.; Hiraki, Y.; Sakamaki, I.; Yamamoto, Y.; et al. Mechanism Underlying Linezolid-induced Thrombocytopenia in a Chronic Kidney Failure Mouse Model. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2017, 8, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Xu, N.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Cao, C.; Chen, L. Linezolid-induced pure red cell aplasia: A case report and literature review. J. Int. Med. Res. 2018, 46, 4837–4844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guglielmetti, L.; Le Dû, D.; Jachym, M.; Henry, B.; Martin, D.; Caumes, E.; Veziris, N.; Métivier, N.; Robert, J. MDR-TB Management Group of the French National Reference Center for Mycobacteria and the Physicians of the French MDR-TB Cohort. Compassionate Use of Bedaquiline for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Interim Analysis of a French Cohort. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajima, M.; Kato, Y.; Matsumoto, J.; Hirosawa, I.; Suzuki, M.; Takashio, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Nishi, Y.; Yamada, H. Linezolid-Induced Thrombocytopenia Is Caused by Suppression of Platelet Production via Phosphorylation of Myosin Light Chain 2. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016, 39, 1846–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, W.B.; Trotta, R.F.; Rector, J.T.; Tjaden, J.A.; Barile, A.J. Mechanisms for Linezolid-Induced Anemia and Thrombocytopenia. Ann. Pharmacother. 2003, 37, 517–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.S.; Jang, J.G.; Lee, J.; Choi, K.J.; Park, J.E. Risk factors for peripheral neuropathy in patients on linezolid-containing regimens for drug-resistant TB. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2023, 27, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, D.; Hu, X.; Shi, L.; Wang, D.; Chen, G. Linezolid-related adverse effects in the treatment of rifampicin resistant tuberculosis: A retrospective study. J. Chemother. 2023, 35, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressler, A.M.; Zimmer, S.M.; Gilmore, J.L.; Somani, J. Peripheral neuropathy associated with prolonged use of linezolid. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004, 4, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnu, V.Y.; Modi, M.; Goyal, M.K.; Lal, V. Linezolid Induced Reversible Peripheral Neuropathy. Am. J. Ther. 2016, 23, 1839–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotgiu, G.; Centis, R.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Alffenaar, J.-W.C.; Anger, H.A.; Caminero, J.A.; Castiglia, P.; Lorenzo, S.D.; Ferrara, G.; Koh, W.-J.; et al. Efficacy, safety and tolerability of linezolid containing regimens in treating MDR-TB and XDR-TB: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2012, 40, 1430–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, W.; Liu, M.; Zhan, S.; Zhang, H.; Deng, G.; Chen, X. Linezolid-Associated Neuropathy in Patients with MDR/XDR Tuberculosis in Shenzhen, China. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 2617–2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkyi, O.; Achar, J.; Gurbanova, E.; Hovhannesyah, A.; Lomtadze, N.; Ciobanu, A.; Skrahina, A.; Dravniece, G.; Kuksa, L.; Rich, M.L.; et al. Effectiveness and safety of modified fully oral 9-month treatment regimens for rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis: A prospective cohort study-PubMed. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1151–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kang, B.H.; Ryu, W.Y.; Um, S.J.; Roh, M.S.; Son, C. Is Severe and Long-lasting Linezolid-induced Optic Neuropathy Reversible? Intern Med. 2018, 57, 3611–3613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agashe, P.; Doshi, A. Linezolid induced optic neuropathy in a child treated for extensively drug resistant tuberculosis: A case report and review of literature. Saudi J. Ophthalmol. 2019, 33, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, S.; Das, M.; Laxmeshwar, C.; Jonckheere, S.; Thi, S.S.; Isaakidis, P. Linezolid-Associated Optic Neuropathy in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis Patients in Mumbai, India. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Y.S.; Lee, C.K. Optic Neuropathy after Taking Linezolid. J. Korean Ophthalmol. Soc. 2019, 60, 1363–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallabhaneni, S.; Mendonca, T.M.; Nayak, R.R.; Kamath, G.; Kamath, A. Linezolid induced toxic optic neuropathy in drug resistant tuberculosis-A case series. Indian J. Tuberc. 2024, 71, 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandariz-Nunez, D.; Hernandez-Corredoira, V.; Guarc-Prades, E.; Garcia-Navarro, B. Optic neuropathy associated with linezolid: Systematic review of cases. Farm. Hosp. 2019, 43, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Zhang, F.; Chen, Z.; Huang, R.; Xia, J.; Liu, J. Successful treatment of linezolid-induced severe lactic acidosis with continuous venovenous hemodiafiltration: A case report. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oehadian, A.; Santoso, P.; Menzies, D.; Ruslami, R. Concise Clinical Review of Hematologic Toxicity of Linezolid in Multidrug-Resistant and Extensively Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: Role of Mitochondria. Tuberc. Respir. Dis. 2022, 85, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Takane, H.; Ogawa, K.; Isagawa, S.; Hirota, T.; Higuchi, S.; Horii, T.; Otsubo, K.; Ieiri, I. Population pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of linezolid and a hematologic side effect, thrombocytopenia, in Japanese patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 1867–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, B.; Dietze, R.; Hadad, D.J.; Molino, L.P.; Maciel, E.L.; Boom, W.H.; Palaci, M.; Johnson, J.L.; Peloquin, C.A. Population pharmacokinetics of linezolid in adults with pulmonary tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3981–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Hu, Y.; Xu, P.; Xu, T.; Chen, C.; He, L.; Zhou, M.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Yu, X.; et al. Expert consensus statement on therapeutic drug monitoring and individualization of linezolid. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 967311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onita, T.; Ishihara, N.; Ikebuchi, A.; Yano, T.; Nishimura, N.; Tamaki, H.; Ikawa, K.; Morikawa, N.; Naora, K. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic simulation for the quantitative risk assessment of linezolid-associated thrombocytopenia. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2022, 47, 2041–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galar, A.; Valerio, M.; Muñoz, P.; Alcalá, L.; García-González, X.; Burillo, A.; Sanjurjo, M.; Grau, S.; Bouza, E. Systematic therapeutic drug monitoring for linezolid: Variability and clinical impact. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00687-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, D.; Marriott, D.J.; Gervasoni, C. Hematological toxicities associated with linezolid therapy in adults: Key findings and clinical considerations. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 16, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Elsen, S.H.J.; Akkerman, O.W.; Jongedijk, E.M.; Wessels, M.; Ghimire, S.; Van Der Werf, T.S.; Touw, D.J.; Bolhuis, M.S.; Alffenaar, J.W.C. Therapeutic drug monitoring using saliva as matrix: An opportunity for linezolid, but challenge for moxifloxacin. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, 55, 1901903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alffenaar, J.W.C.; Kosterink, J.G.W.; Van Altena, R.; Van Der Werf, T.S.; Uges, D.R.A.; Proost, J.H. Limited sampling strategies for therapeutic drug monitoring of linezolid in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Ther. Drug Monit. 2010, 32, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xavier, R.M.; Sharumathi, S.M.; Kanniyappan Parthasarathy, A.; Mani, D.; Mohanasundaram, T. Limited sampling strategies for therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tuberculosis medications: A systematic review of their feasibility and clinical utility. Tuberculosis 2023, 141, 102367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Query | Hits |

|---|---|---|

| PubMed | (((tbc OR tuberculosis OR tuberculosis OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infection” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infections”) AND (“Multidrug-Resistant” OR “Multidrug Resistant” OR MDR OR “Multi-Drug Resistant” OR “Multi Drug Resistant” OR “Drug-Resistant” OR “Drug Resistant”)) AND (Linezolid OR Linezolide OR Zyvox OR Oxazolidinones)) AND (“Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions” OR “Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Side Effects” OR “Drug Side Effect” OR “effects drug side” OR “Side effect drug” OR “Side effects drug” OR “Adverse Drug Reaction” OR “Adverse Drug Reactions” OR “Drug reaction adverse” OR “Drug reactions adverse” OR “Reactions adverse drug” OR “Adverse drug event” OR “adverse drug events” OR “Drug event adverse” OR “drug events adverse” OR “side effects of drugs” OR “Drug toxicity” OR “toxicity drug” OR “Drug toxicities” OR “toxicities drug”) | 80 |

| Scopus | (TITLE-ABS-KEY (tbc OR tuberculosis OR tuberculoses OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infection” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infections”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“multidrug-resistant” OR “multidrug resistant” OR mdr OR “multi-drug resistant” OR “multi drug resistant” OR “drug-resistant” OR “drug resistant”) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (linezolid OR linezolide OR zyvox OR oxazolidinones) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY (“drug related side effects and adverse reactions” OR “drug-related side effects and adverse reaction” OR “drug related side effects and adverse reaction” OR “drug side effects” OR “drug side effect” OR “effects drug side” OR “side effect drug” OR “side effects drug” OR “adverse drug reaction” OR “adverse drug reactions” OR “drug reaction adverse” OR “drug reactions adverse” OR “reactions adverse drug” OR “adverse drug event” OR “adverse drug events” OR “drug event adverse” OR “drug events adverse” OR “side effects of drugs” OR “drug toxicity” OR “toxicity drug” OR “drug toxicities” OR “toxicities drug”)) | 120 |

| Sage | ‘tbc OR tuberculosis OR tuberculoses OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infection” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infections” AND “Multidrug-Resistant” OR “Multidrug Resistant” OR MDR OR “Multi-Drug Resistant” OR “Multi Drug Resistant” OR “Drug-Resistant” OR “Drug Resistant” AND Linezolid OR Linezolide OR Zyvox OR Oxazolidinones AND “Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions” OR “Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Side Effects” OR “Drug Side Effect” OR “effects drug side” OR “Side effect drug” OR “Side effects drug” OR “Adverse Drug Reaction” OR “Adverse Drug Reactions” OR “Drug reaction adverse” OR “Drug reactions adverse” OR “Reactions adverse drug” OR “Adverse drug event” OR “adverse drug events” OR “Drug event adverse” OR “drug events adverse” OR “side effects of drugs” OR “Drug toxicity” OR “toxicity drug” OR “Drug toxicities” OR “toxicities drug”’ | 121 |

| ProQuest | (tbc OR tuberculosis OR tuberculosis OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infection” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis” OR “mycobacterium tuberculosis infections”) AND (“Multidrug-Resistant” OR “Multidrug Resistant” OR MDR OR “Multi-Drug Resistant” OR “Multi Drug Resistant” OR “Drug-Resistant” OR “Drug Resistant”) AND (Linezolid OR Linezolide OR Zyvox OR Oxazolidinones) AND (“Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reactions” OR “Drug-Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Related Side Effects and Adverse Reaction” OR “Drug Side Effects” OR “Drug Side Effect” OR “effects drug side” OR “Side effect drug” OR “Side effects drug” OR “Adverse Drug Reaction” OR “Adverse Drug Reactions” OR “Drug reaction adverse” OR “Drug reactions adverse” OR “Reactions adverse drug” OR “Adverse drug event” OR “adverse drug events” OR “Drug event adverse” OR “drug events adverse” OR “side effects of drugs” OR “Drug toxicity” OR “toxicity drug” OR “Drug toxicities” OR “toxicities drug”) | 329 |

| Domain | Parameters | Frequency | Recommended Actions | Prevention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hematologic | Complete Blood Count (CBC): hemoglobin, platelets, leukocytes. | Weekly CBC for the first 8 weeks, then every 2 weeks until month 6, then monthly. Monitoring points: baseline, week 2, end of treatment, and follow-up at 6 and 12 months post-treatment. | 1. If Hb 10–13 g/dL or platelets 50,000–109,000/µL: provide supportive care or hematinic therapy (e.g., folic acid). 2. If Hb < 10 g/dL or platelets < 100,000/µL: reduce dose to 300 mg once daily. 3. If Hb < 8 g/dL or symptomatic anemia: give blood transfusion and consider immediate discontinuation of linezolid. 4. If linezolid must be discontinued due to adverse reactions, it can be stopped after 9 weeks of therapy. Avoid discontinuation before week 9 unless clinically necessary. | 1. Avoid dosing 1200 mg once daily or 600 mg twice daily. 2. For high-risk patients (renal impairment, baseline cytopenia, age > 60 years), consider a lower regimen of 600 mg once daily or 300 mg once daily. 3. Consider therapeutic TDM. Maintain trough concentration < 2 mg/L. |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Individual assessment using Modified Brief Peripheral Neuropathy Scale (BPNS), Toronto Clinical Neuropathy Score, and symptom screening (paresthesia, numbness, vibration sense, reflexes). | At treatment initiation and monthly during therapy. Monitoring points: baseline, week 2, end of treatment, and follow-up at 6 and 12 months post-treatment. | 1. Mild symptoms: continue linezolid and add symptomatic therapy (e.g., vitamin B6, gabapentin). 2. Moderate to severe symptoms: consult a clinician and consider dose adjustment to 300 mg once daily or discontinuation if symptoms progress. | 1. Avoid 1200 mg once daily. 2. Early vitamin B6 supplementation may reduce neuropathy progression. 3. Consider TDM. Maintain trough concentration < 2 mg/L. |

| Optic neuropathy | Snellen chart and Ishihara test. | At treatment initiation and monthly during therapy. Monitoring points: baseline, week 2, end of treatment, and follow-up at 6 and 12 months post-treatment. | 1. If symptoms occur (decreased vision, reduced visual acuity, color vision loss): discontinue linezolid immediately. 2. Consider clinician consultation. | 1. Consider prednisone 1 mg/kg/day during therapy. 2. Consider TDM. Maintain trough concentration < 2 mg/L. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oktaviani, E.; Anggadiredja, K.; Amalia, L. Adverse Drug Reaction to Linezolid in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review. Med. Sci. 2026, 14, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010003

Oktaviani E, Anggadiredja K, Amalia L. Adverse Drug Reaction to Linezolid in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review. Medical Sciences. 2026; 14(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleOktaviani, Emy, Kusnandar Anggadiredja, and Lia Amalia. 2026. "Adverse Drug Reaction to Linezolid in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review" Medical Sciences 14, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010003

APA StyleOktaviani, E., Anggadiredja, K., & Amalia, L. (2026). Adverse Drug Reaction to Linezolid in Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis: A Systematic Review. Medical Sciences, 14(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci14010003