Nuclear Medicine Imaging Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

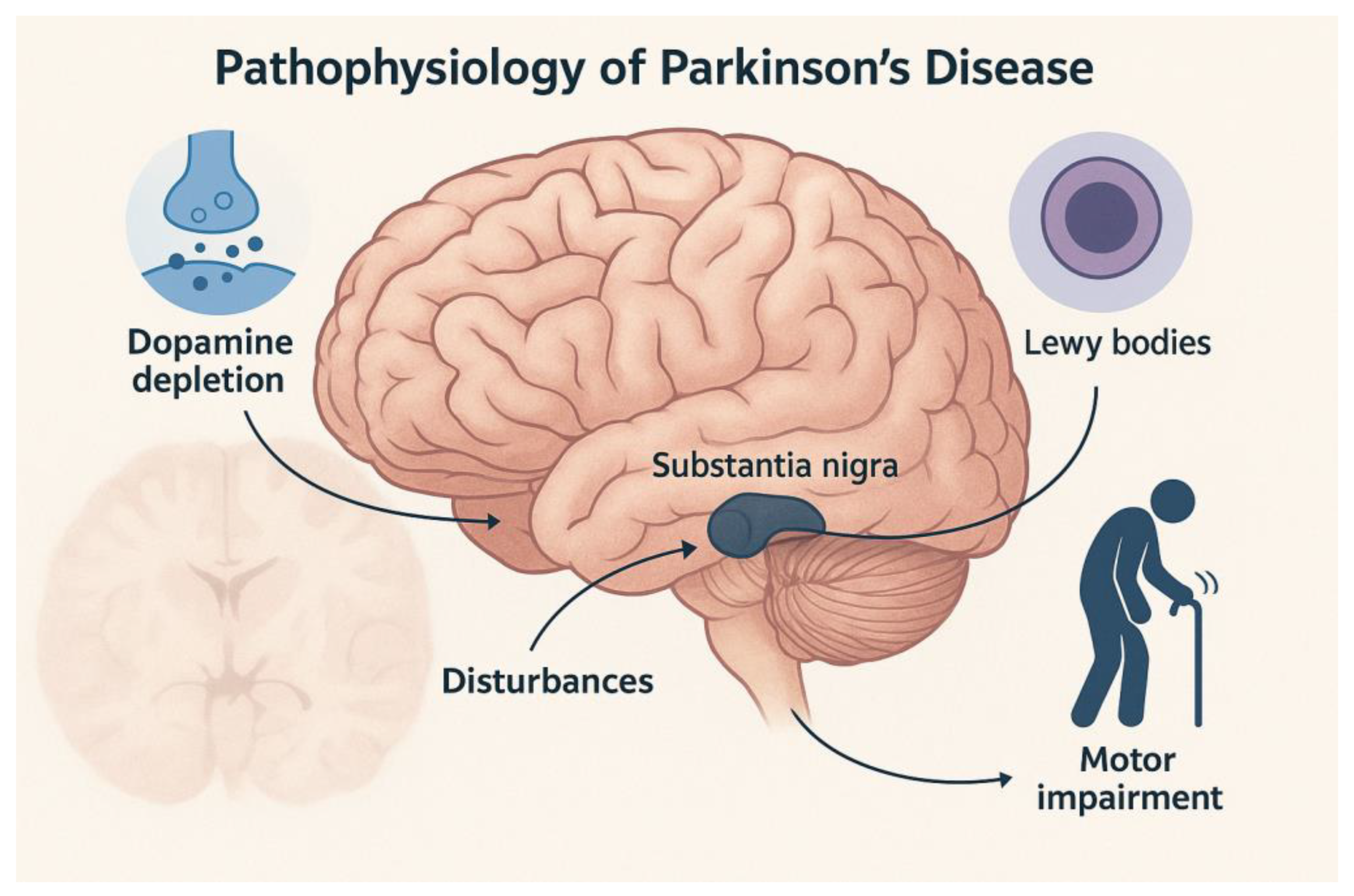

2. Clinical History of Parkinson’s Disease

Preclinical, Prodromal, and Clinical Stages of PD

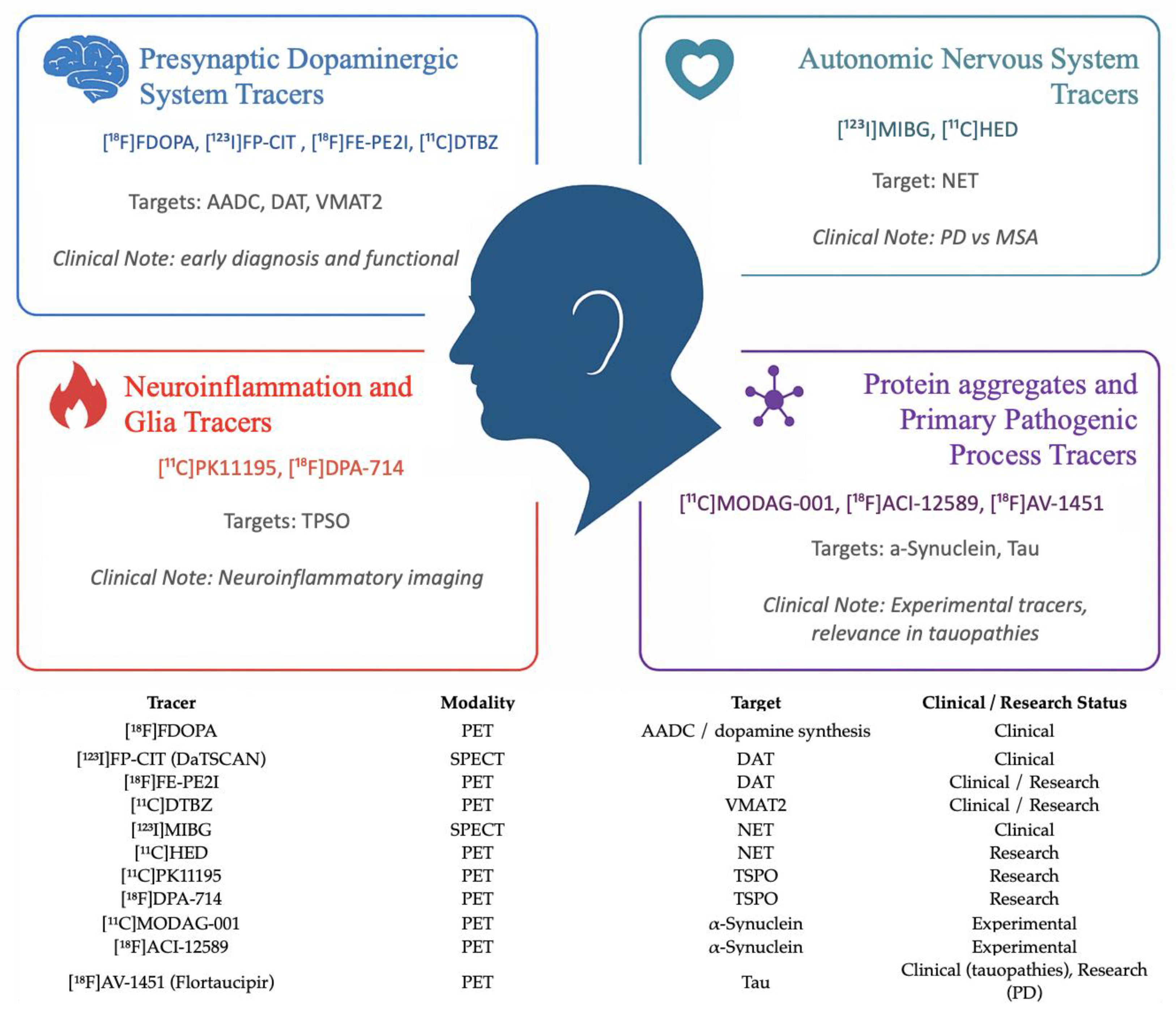

3. Radiotracers in Parkinson’s Disease

- -

- [^18F]FDOPA: approved for PET imaging to evaluate presynaptic dopaminergic function and assess nigrostriatal integrity [30];

- -

- [^123I]FP-CIT (DaTSCAN): approved for SPECT imaging of the presynaptic dopaminergic system, assessing dopamine transporter (DAT) availability in the striatum [31];

- -

- [^123I]MIBG: used in SPECT imaging to assess cardiac sympathetic innervation, useful in differentiating PD from multiple system atrophy (MSA) and progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) [32]. These tracers represent the current standard of care in clinical molecular imaging of PD, aiding in diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and disease staging (Table 1).

4. The Dopaminergic System

4.1. Dopamine Synthesis and Metabolism

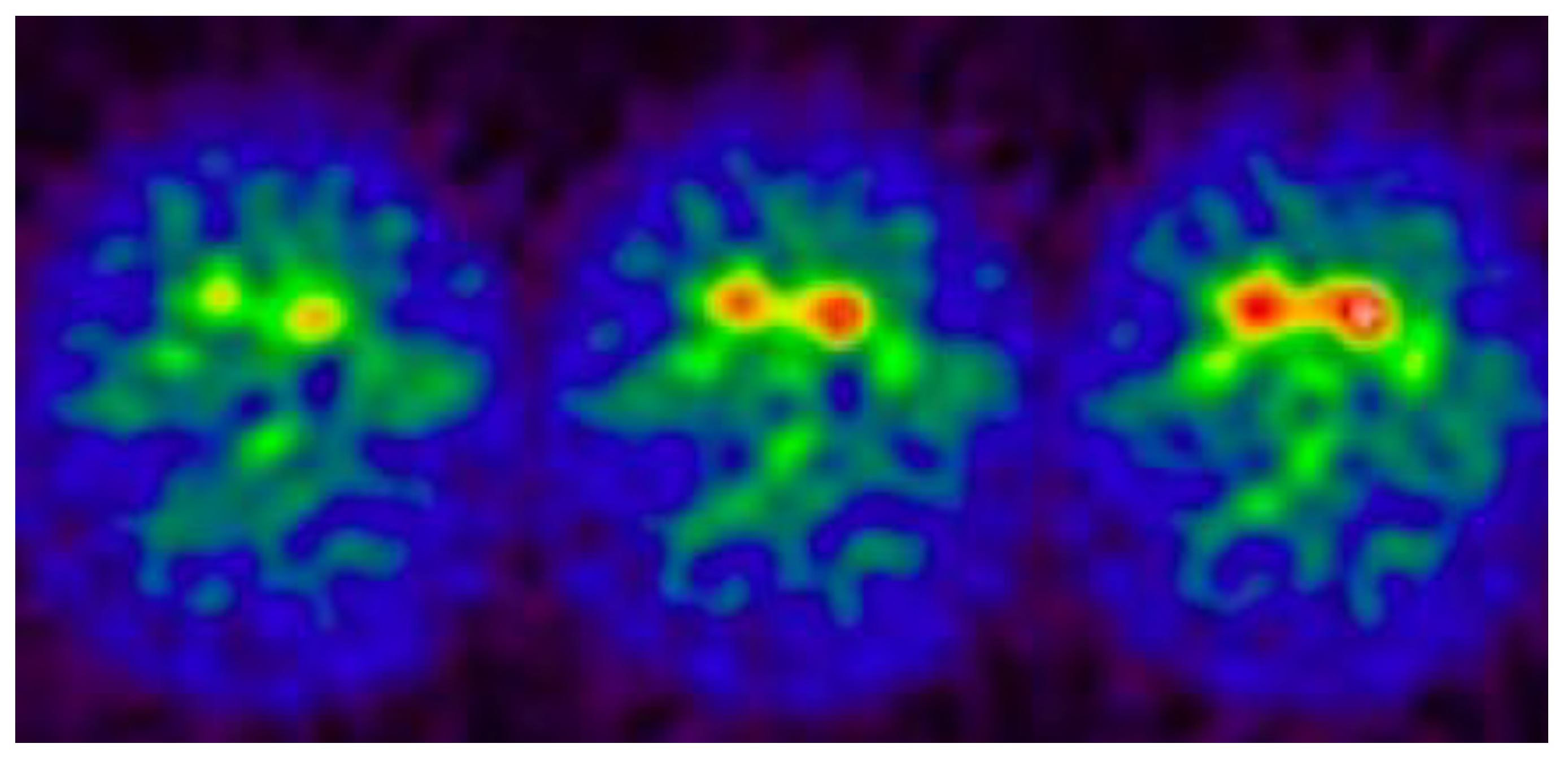

4.2. Dopamine Transporter (DAT) Activity

4.3. Vesicular Monoamine Transporter Type 2 (VMAT2)

4.4. Dopamine Receptors

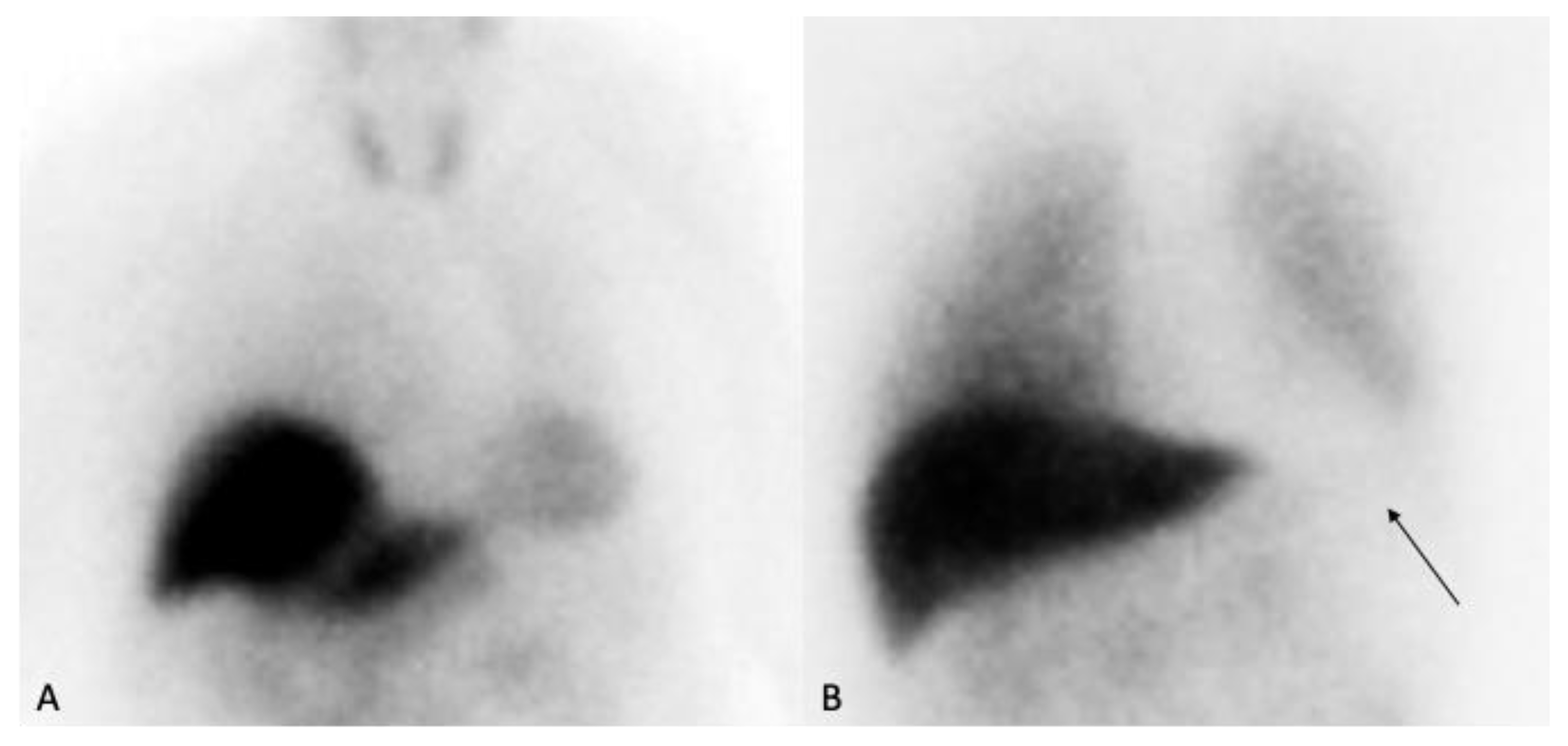

5. [^123I]MIBG SPECT Imaging

6. Neural Connectivity, Cerebral Blood Flow, and Metabolism

[^18F] FDG PET Imaging

7. Tau and Beta-Amyloid Imaging

8. PET/MRI Systems in PD and Parkinsonism

9. New Targets in PD Imaging

9.1. Alpha-Synuclein

9.2. Microglia

10. What’s New Since 2020: Multicenter Imaging, and SV2A/Synaptic Density

11. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tolosa, E.; Garrido, A.; Scholz, S.W.; Poewe, W. Challenges in the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS clinical diagnostic criteria for Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booij, J.; Knol, R.J.J. SPECT imaging of the dopaminergic system in (premotor) Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2007, 13 (Suppl. 3), S425–S428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, P.; Borghammer, P. Molecular imaging and the neuropathologies of Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2012, 11, 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshuis, S.A.; Jager, P.L.; Maguire, R.P.; Jonkman, S.; Dierckx, R.A.; Leenders, K.L. Direct comparison of FP-CIT SPECT and F-DOPA PET in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2009, 36, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marek, K.; Jennings, D. Can we image premotor Parkinson disease? Neurology 2009, 72 (Suppl. 7), S21–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edison, P.; Ahmed, I.; Fan, Z.; Hinz, R.; Gelosa, G.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.; Walker, Z.; Turkheimer, F.E.; Brooks, D.J. Microglia, amyloid, and glucose metabolism in Parkinson’s disease with and without dementia. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 938–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.K.; Mecca, A.P.; Naganawa, M.; Finnema, S.J.; Toyonaga, T.; Lin, S.F.; Najafzadeh, S.; Ropchan, J.; Lu, Y.; McDonald, J.W.; et al. Assessing synaptic density in Alzheimer disease with SV2A PET imaging. J. Nucl. Med. 2018, 59, 603–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, M.T.; Oertel, W.H.; Surmeier, D.J.; Geibl, F.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease—A key disease hallmark with therapeutic potential. Mol. Neurodegener. 2023, 18, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdurand, M.; Levigoureux, E.; Zeinyeh, W.; Berthier, L.; Mendjel-Herda, M.; Cadarossanesaib, F.; Bouillot, C.; Iecker, T.; Terreux, R.; Lancelot, S.; et al. In silico, in vitro, and in vivo evaluation of new candidates for α-synuclein PET imaging. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 5083–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simuni, T.; Uribe, L.; Cho, H.J.; Caspell-Garcia, C.; Coffey, C.; Siderowf, A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Shaw, L.M.; Seibyl, J.; Singleton, A.; et al. Clinical and dopamine transporter imaging characteristics of non-manifest LRRK2 and GBA mutation carriers in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative (PPMI): A cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol. 2020, 19, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jellinger, K.A. The pathomechanisms underlying Parkinson’s disease. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2014, 14, 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beach, T.G.; Sue, L.I.; Adler, C.H.; Lue, J.E.; Walker, L.M.; Shill, B.J.; Akiyama, H.; Caviness, J.N.; Shill, H.A.; Sabbagh, M.N.; et al. Multi-organ distribution of phosphorylated alpha-synuclein histopathology in subjects with Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 689–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelpi, E.; Compta, J.; Gaig, C.; Rey, M.J.; Martí, A.; Ribalta, J.; Martí, M.J.; Hernández, I.; Valldeoriola, F.; Reñé, R.; et al. Multiple organ involvement by alpha-synuclein pathology in Lewy body disorders. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1010–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilton, D.; Stephens, M.; Kirk, L.; Edwards, P.; Potter, R.; Zajicek, J.; Broughton, E.; Hagan, H.; Carroll, C. Accumulation of alpha-synuclein in the bowel of patients in the pre-clinical phase of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2014, 127, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, K.M.; Keshavarzian, A.; Dodiya, H.B.; Jakate, S.; Kordower, J.H. Is alpha-synuclein in the colon a biomarker for premotor Parkinson’s disease? Evidence from 3 cases. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokholm, M.G.; Danielsen, E.H.; Hamilton-Dutoit, S.J.; Borghammer, P. Pathological alpha-synuclein in gastrointestinal tissues from prodromal Parkinson disease patients. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, R.D.; Petrovitch, K.H.; White, D.M.; Ross, J.D.; Masaki, C.F.; Tanner, L.H.; Grandinetti, A.; Blanchette, P.L.; Popper, J.S.; Ross, G.W. Frequency of bowel movements and the future risk of Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 2001, 57, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams-Carr, K.L.; Bestwick, A.; Shribman, M.; Lees, L.; Schrag, A.J.; Noyce, A.J. Constipation preceding Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 87, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noyce, A.J.; Lees, A.J.; Schrag, A.E. The prediagnostic phase of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2016, 87, 871–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchihara, T.; Giasson, B.I. Propagation of alpha-synuclein pathology: Hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2016, 131, 49–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berg, D.; Adler, C.H.; Bloem, B.R.; Chan, P.; Gasser, T.; Goetz, C.G.; Halliday, G.; Lang, A.E.; Lewis, S.; Li, Y.; et al. Movement disorder society criteria for clinically established early Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2018, 33, 1643–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kordower, J.H.; Olanow, C.W.; Dodiya, H.B.; Chu, Y.; Beach, T.G.; Adler, C.H.; Halliday, G.M.; Bartus, R.T. Disease duration and the integrity of the nigrostriatal system in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2013, 136, 2419–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilker, R.; Schweitzer, K.; Coburger, S.; Ghaemi, M.; Weisenbach, S.; Jacobs, A.H.; Rudolf, J.; Herholz, K.; Heiss, W.D. Nonlinear progression of Parkinson disease as determined by serial positron emission tomographic imaging of striatal fluorodopa F 18 activity. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stern, M.B.; Lang, A.E.; Poewe, W. Toward a redefinition of Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2012, 27, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, S.; Berg, D.; Gasser, T.; Chen, H.; Yao, C.; Postuma, R.B.; MDS Task Force on the Definition of Parkinson’s Disease. Update of the MDS research criteria for prodromal Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1464–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Gagnon, J.F.; Vendette, M.; Fantini, M.L.; Massicotte-Marquez, J.; Montplaisir, J. Quantifying the risk of neurodegenerative disease in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2009, 72, 1296–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranzo, A.; Fernandez-Arcos, A.; Tolosa, E.; Serradell, M.; Molinuevo, J.L.; Valldeoriola, F.; Gelpi, E.; Vilaseca, I.; Sánchez-Valle, R.; Lladó, A.; et al. Neurodegenerative disorder risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: Study in 174 patients. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e89741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.H.; Boeve, B.F.; Mahowald, M.W. Delayed emergence of a parkinsonian disorder or dementia in 81% of older men initially diagnosed with idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: A 16-year update on a previously reported series. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 744–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnett, E.S.; Firnau, G.; Nahmias, C. Dopamine visualized in the basal ganglia of living man. Nature 1983, 305, 137–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerstens, V.S.; Varrone, A. Dopamine transporter imaging in neurodegenerative movement disorders: PET vs. SPECT. Clin. Transl. Imaging 2020, 8, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshita, M.; Hayashi, M.; Hirai, S. Decreased myocardial accumulation of 123I-meta-iodobenzyl guanidine in Parkinson’s disease. Nucl. Med. Commun. 1998, 19, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, B.; Olafsson, V.; Calabro, F.; Laymon, C.; Tervo-Clemmens, B.; Campbell, E.; Minhas, D.; Montez, D.; Price, J.; Luna, B. Maturation of the human striatal dopamine system revealed by PET and quantitative MRI. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toch, S.R.; Poussier, S.; Micard, E.; Bertaux, M.; Van Der Gucht, A.; Chevalier, E.; Marie, P.Y.; Guedj, E.; Verger, A. Physiological whole-brain distribution of [18F]FDOPA uptake index in relation to age and gender: Results from a voxel-based semi-quantitative analysis. Mol. Imaging Biol. 2019, 21, 549–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, R.; Stoessl, A.J. Imaging the nigrostriatal system to monitor disease progression and treatment-induced complications. Recent Adv. Park. Dis. 2010, 184, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, N.; Kusmirek, J.; Struck, A.F.; Floberg, J.M.; Perlman, S.B.; Gallagher, C.; Hall, L.T. The sensitivity and specificity of F-DOPA PET in a movement disorder clinic. Am. J. Nucl Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 6, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Niethammer, M.; Feigin, A.; Eidelberg, D. Functional neuroimaging in Parkinson’s disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2012, 2, a009274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broussolle, E.; Dentresangle, C.; Landais, P.; Garcia-Larrea, L.; Pollak, P.; Croisile, B.; Hibert, O.; Bonnefoi, F.; Galy, G.; Froment, J.C.; et al. The relation of putamen and caudate nucleus 18F-Dopa uptake to motor and cognitive performances in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Sci. 1999, 166, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politis, M.; Wu, K.; Loane, C.; Quinn, N.P.; Brooks, D.J.; Oertel, W.H.; Lindvall, O.; Piccini, P. Serotonin neuron loss and nonmotor symptoms continue in Parkinson’s patients treated with dopamine grafts. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 128ra41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrish, P.K.; Rakshi, J.S.; Bailey, D.L.; Sawle, G.V.; Brooks, D.J. Measuring the rate of progression and estimating the preclinical period of Parkinson’s disease with [18F]dopa PET. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1998, 64, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chevalme, Y.M.; Montravers, F.; Vuillez, J.P.; Zanca, M.; Fallais, C.; Oustrin, J.; Talbot, J.N. FDOPA-(18F): A PET radiopharmaceutical recently registered for diagnostic use in countries of the European Union. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2007, 50, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Li, C.T.; Palotti, M.; Holden, J.E.; Oh, J.; Okonkwo, O.; Christian, B.T.; Bendlin, B.B.; Buyan-Dent, L.; Harding, S.J.; Stone, C.K. A dual-tracer study of extrastriatal 6-[18F]fluoro-m-tyrosine and 6-[18F]-fluoro-l-dopa uptake in Parkinson’s disease. Synapse 2014, 68, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, C.L.; Christian, B.T.; Holden, J.E.; Dejesus, O.T.; Nickles, R.J.; Buyan-Dent, L.; Bendlin, B.B.; Harding, S.J.; Stone, C.K.; Mueller, B.; et al. A within-subject comparison of 6-[18F]fluoro-m-tyrosine and 6-[18F]fluoro-L-dopa in Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2011, 26, 2032–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nirenberg, M.J.; Vaughan, R.A.; Uhl, G.R.; Kuhar, M.J.; Pickel, V.M. The dopamine transporter is localized to dendritic and axonal plasma membranes of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 436–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciliax, B.J.; Heilman, C.; Demchyshyn, L.L.; Pristupa, Z.B.; Ince, E.; Hersch, S.M.; Niznik, H.B.; Levey, A.I. The dopamine transporter: Immunochemical characterization and localization in brain. J. Neurosci. 1995, 15 Pt 1, 1714–1723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kish, S.J.; Shannak, K.; Hornykiewicz, O. Uneven pattern of dopamine loss in the striatum of patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: Pathophysiologic and clinical implications. N. Engl. J. Med. 1988, 318, 876–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batchelor, M.; Schenk, J.O. Protein kinase A activity may kinetically upregulate the striatal transporter for dopamine. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18, 10304–10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.; Reith, M.E. Structure and function of the dopamine transporter. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2000, 405, 329–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melikian, H.E.; Buckley, K.M. Membrane trafficking regulates the activity of the human dopamine transporter. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 7699–7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressan, R.A.; Crippa, J.A. The role of dopamine in reward and pleasure behavior—Review of data from preclinical research. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 2005, 427, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, J.S.; Volkow, N.D.; Wolf, A.P.; Dewey, S.L.; Schlyer, D.J.; Macgregor, R.R.; Hitzemann, R.; Logan, J.; Bendriem, B.; Gatley, S.J.; et al. Mapping cocaine binding sites in human and baboon brain in vivo. Synapse 1989, 4, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkow, N.D.; Ding, Y.S.; Fowler, J.S.; Wang, G.J.; Logan, J.; Gatley, S.J.; Schlyer, D.J.; Pappas, N. A new PET ligand for the dopamine transporter: Studies in the human brain. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, 36, 2162–2168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.Y.; Ciliax, B.J.; Stebbins, G.; Jaffar, S.; Joyce, J.N.; Cochran, E.J.; Kordower, J.H.; Mash, D.C.; Levey, A.I.; Mufson, E.J. Dopamine transporter-immunoreactive neurons decrease with age in the human substantia nigra. J. Comp. Neurol. 1999, 409, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherman, D.; Desnos, C.; Darchen, F.; Pollak, P.; Javoy-Agid, F.; Agid, Y. Striatal dopamine deficiency in Parkinson’s disease: Role of aging. Ann. Neurol. 1989, 26, 551–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Seibyl, J.P.; Malison, R.T.; Laruelle, M.; Wallace, E.; Zoghbi, S.S.; Zea-Ponce, Y.; Baldwin, R.M.; Charney, D.S.; Hoffer, P.B. Age-related decline in striatal dopamine transporter binding with iodine-123-beta-CIT SPECT. J. Nucl. Med. 1995, 36, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Uhl, G.R. Neurotransmitter transporters (plus): A promising new gene family. Trends Neurosci. 1992, 15, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seibyl, J.P.; Marek, K.L.; Quinlan, D.; Sheff, K.; Zoghbi, S.; Zea-Ponce, Y.; Baldwin, R.M.; Fussell, B.; Smith, E.O.; Charney, D.S.; et al. Decreased single-photon emission computed tomographic [123I] beta-CIT striatal uptake correlates with symptom severity in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1995, 38, 589–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson Study Group. A multicenter assessment of dopamine transporter imaging with DOPASCAN/SPECT in parkinsonism. Neurology 2000, 55, 1540–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strafella, A.P.; Bohnen, N.I.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Eidelberg, D.; Pavese, N.; Van Eimeren, T.; Piccini, P.; Politis, M.; Thobois, S.; Ceravolo, R.; et al. Molecular imaging to track Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonisms: New imaging frontiers. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.; Ranjan, R.; Verma, R.; Belho, E.S.; Malik, D.; Mahajan, H. Correlation of 99mTc-TRODAT-1 SPECT imaging findings and clinical staging of Parkinson disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2019, 44, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinaz, S.; Chow, C.; Kuo, P.H.; Krupinski, E.A.; Blumenfeld, H.; Louis, E.D.; Zubal, G. Semiquantitative analysis of dopamine transporter scans in patients with Parkinson disease. Clin. Nucl. Med. 2018, 43, e1–e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinkle, J.T.; Perepezko, K.; Mills, K.A.; Mari, Z.; Butala, A.; Dawson, T.M.; Pantelyat, A.; Rosenthal, L.S.; Pontone, G.M. Dopamine transporter availability reflects gastrointestinal dysautonomia in early Parkinson disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 55, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ceravolo, R.; Frosini, D.; Poletti, M.; Kiferle, L.; Pagni, C.; Mazzucchi, S.; Volterrani, D.; Bonuccelli, U. Mild affective symptoms in de novo Parkinson’s disease patients: Relationship with dopaminergic dysfunction. Eur. J. Neurol. 2013, 20, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frosini, D.; Unti, E.; Guidoccio, F.; Del Gamba, C.; Puccini, G.; Volterrani, D.; Bonuccelli, U.; Ceravolo, R. Mesolimbic dopaminergic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease depression: Evidence from a 123I-FP-CIT SPECT investigation. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 1143–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giuda, D.; Camardese, G.; Bentivoglio, A.R.; Cocciolillo, F.; Guidubaldi, A.; Pucci, L.; Bruno, I.; Janiri, L.; Giordano, A.; Fasano, A. Dopaminergic dysfunction and psychiatric symptoms in movement disorders: A 123I-FP-CIT SPECT study. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2012, 39, 1937–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.W.; Oh, Y.S.; Hwang, E.J.; Ryu, D.W.; Lee, K.S.; Lyoo, C.H.; Kim, J.S. “Depressed” caudate and ventral striatum dopamine transporter availability in de novo depressed Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2019, 132, 104563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepel, F.J.; Brønnick, K.S.; Booij, J.; Ravina, B.M.; Lebedev, A.V.; Pereira, J.B.; Grüner, R.; Aarsland, D. Cognitive executive impairment and dopaminergic deficits in de novo Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2014, 29, 1802–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobili, F.; Campus, C.; Arnaldi, D.; De Carli, F.; Cabassi, G.; Brugnolo, A.; Dessi, B.; Morbelli, S.; Sambuceti, G.; Abbruzzese, G. Cognitive-nigrostriatal relationships in de novo, drug-naïve Parkinson’s disease patients: A [123I]FP-CIT SPECT study. Mov. Disord. 2010, 25, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y.S.; Kim, J.S.; Hwang, E.J.; Lyoo, C.H. Striatal dopamine uptake and olfactory dysfunction in patients with early Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2018, 56, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, K.; Kim, K.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, J.M.; Kim, B.S.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, I.J. Correlation between the availability of dopamine transporter and olfactory function in healthy subjects. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 1756–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Lohman, C.; Kerik, N.E.; Díaz-Meneses, I.E.; Cervantes-Arriaga, A.; Rodríguez-Violante, M. Diagnostic utility of [11C]DTBZ positron emission tomography in clinically uncertain parkinsonism: Experience of a single tertiary center. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2018, 70, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, L.H.; Weng, Y.H.; Wen, M.C.; Hsiao, I.T.; Lin, K.J. Quantitative study of 18F-(+)-DTBZ image: Comparison of PET template-based and MRI-based image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Samii, A.; Sossi, V.; Ruth, T.J.; Schulzer, M.; Holden, J.E.; Wudel, J.; Pal, P.K.; de la Fuente-Fernandez, R.; Calne, D.B.; et al. In vivo positron emission tomographic evidence for compensatory changes in presynaptic dopaminergic nerve terminals in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Baek, S.M.; Ho, D.H.; Suk, J.E.; Cho, E.D.; Lee, S.J. Dopamine promotes formation and secretion of non-fibrillar alpha-synuclein oligomers. Exp. Mol. Med. 2011, 43, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilbourn, M.R.; Frey, K.A.; Vander Borght, T.; Sherman, P.S. Effects of dopaminergic drug treatments on in vivo radioligand binding to brain vesicular monoamine transporters. Nucl. Med. Biol. 1996, 23, 467–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fuente-Fernández, R.; Schulzer, M.; Kuramoto, L.; Cragg, J.; Ramachandiran, N.; Au, W.L.; Mak, E.; McKenzie, J.; McCormick, S.; Sossi, V.; et al. Age-specific progression of nigrostriatal dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2011, 69, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, L.C.; Dore, V.; Villemagne, V.L.; Xu, S.; Finkelstein, D.; Barnham, K.J.; Rowe, C. Using 18F-AV-133 VMAT2 PET Imaging to Monitor Progressive Nigrostriatal Degeneration in Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2023, 101, e2314–e2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsinga, P.H.; Hatano, K.; Ishiwata, K. PET tracers for imaging of the dopaminergic system. Curr. Med. Chem. 2006, 13, 2139–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, J.; Christian, B.T.; Dunigan, K.A.; Shi, B.; Narayanan, T.K.; Satter, M.; Mantil, J. Brain imaging of 18F-fallypride in normal volunteers: Blood analysis, distribution, test-retest studies, and preliminary assessment of sensitivity to aging effects on dopamine D2/D3 receptors. Synapse 2002, 46, 170–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasinen, V.; Vahlberg, T.; Stoessl, A.J.; Strafella, A.P.; Antonini, A. Dopamine Receptors in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis of Imaging Studies. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1781–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laruelle, M. Imaging synaptic neurotransmission with in vivo binding competition techniques: A critical review. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2000, 20, 423–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shotbolt, P.; Tziortzi, A.C.; Searle, G.E.; Colasanti, A.; van der Aart, J.; Abanades, S.; Plisson, C.; Miller, S.R.; Huiban, M.; Beaver, J.D.; et al. Within-subject comparison of [11C]-(+)-PHNO and [11C]raclopride sensitivity to acute amphetamine challenge in healthy humans. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cropley, V.L.; Fujita, M.; Bara-Jimenez, W.; Brown, A.K.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sangare, J.; Herscovitch, P.; Pike, V.W.; Hallett, M.; Nathan, P.J.; et al. Pre- and post-synaptic dopamine imaging and its relation with frontostriatal cognitive function in Parkinson disease: PET studies with [11C]NNC112 and [18F]FDOPA. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 2008, 163, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinne, J.O.; Laihinen, A.; Någren, K.; Bergman, J.; Solin, O.; Haaparanta, M.; Ruotsalainen, U.; Rinne, U.K. PET demonstrates different behaviour of striatal dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res 1990, 27, 494–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasinen, V.; Aalto, S.; Någren, K.; Hietala, J.; Sonninen, P.; Rinne, J.O. Extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptors in Parkinson’s disease: A longitudinal study. J. Neural Transm. 2003, 110, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, A.; Leenders, K.L.; Vontobel, P.; Maguire, R.P.; Missimer, J.; Psylla, M. Complementary PET studies of striatal neuronal function in the differential diagnosis between multiple system atrophy and Parkinson’s disease. Brain 1997, 120, 2187–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlaar, A.M.M.; Nijs, T.; de Kessels, A.G.H.; Vreeling, F.W.; Winogrodzka, A.; Mess, W.H.; Tromp, S.C.; van Kroonenburgh, M.J.; Weber, W.E. Diagnostic value of 123I-ioflupane and 123I-iodobenzamide SPECT scans in 248 patients with parkinsonian syndromes. Eur. Neurol. 2008, 59, 258–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Fougère, C.; Pöpperl, G.; Levin, J.; Wängler, B.; Böning, G.; Uebleis, C.; Cumming, P.; Bartenstein, P.; Bötzel, K.; Tatsch, K. The value of the dopamine D2/3 receptor ligand 18F-desmethoxyfallypride for the differentiation of idiopathic and non-idiopathic parkinsonian syndromes. J. Nucl. Med. 2010, 51, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deutschländer, A.; la Fougère, C.; Boetzel, K.; Albert, N.L.; Gildehaus, F.J.; Bartenstein, P.; Xiong, G.; Cumming, P. Occupancy of pramipexole (Sifrol) at cerebral dopamine D2/3 receptors in Parkinson’s disease patients. Neuroimage Clin. 2016, 12, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyce, J.N.; Millan, M.J. Dopamine D3 receptor agonists for protection and repair in Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2007, 7, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boileau, I.; Guttman, M.; Rusjan, P.; Adams, J.R.; Houle, S.; Tong, J.; Hornykiewicz, O.; Furukawa, Y.; Wilson, A.A.; Kapur, S.; et al. Decreased binding of the D3 dopamine receptor-preferring ligand [11C]-(+)-PHNO in drug-naive Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2009, 132 Pt 5, 1366–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, C.P.; Mansouri, E.; Tong, J.; Wilson, A.A.; Houle, S.; Boileau, I.; Duvauchelle, T.; Robert, P.; Schwartz, J.C.; Le Foll, B. Occupancy of dopamine D2 and D3 receptors by a novel D3 partial agonist BP1.4979: A [11C]-(+)-PHNO PET study in humans. Neuropsychopharmacology 2019, 44, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, R.H.; Luedtke, R.R. Challenges in the development of dopamine D2- and D3-selective radiotracers for PET imaging studies. J. Label. Compd. Radiopharm. 2018, 61, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, S.; Amino, T.; Itoh, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Kojo, T.; Uchihara, T.; Tsuchiya, K.; Mori, F.; Wakabayashi, K.; Takahashi, H. Cardiac sympathetic denervation precedes neuronal loss in the sympathetic ganglia in Lewy body disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2005, 109, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashihara, K.; Ohno, M.; Kawada, S.; Okumura, Y. Reduced cardiac uptake and enhanced washout of 123I-MIBG in pure autonomic failure occurs conjointly with Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Nucl. Med. 2006, 47, 1099–1101. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.H.; Yoon, J.K.; Yoon, J.H.; Lee, S.J.; Jo, K.S.; Lee, D.H.; An, Y.-S. The utility of segmental analysis in cardiac I-123 MIBG SPECT in Parkinson’s disease. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2015, 49, 298–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Oh, J.K.; Choi, E.K.; Song, I.U.; Kim, J.S.; Chung, Y.A. Comparison of I-123 MIBG planar imaging and SPECT for the detection of decreased heart uptake in Parkinson disease. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 1421–1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orimo, S.; Suzuki, M.; Inaba, A.; Mizusawa, H. 123I-MIBG myocardial scintigraphy for differentiating Parkinson’s disease from other neurodegenerative parkinsonism: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 494–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaets, S.; Van Acker, F.; Versijpt, J.; Hauth, L.; Goeman, J.; Martin, J.J.; De Deyn, P.P.; Engelborghs, S. Diagnostic value of MIBG cardiac scintigraphy for differential dementia diagnosis. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 30, 864–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, S.; Sakakibara, R.; Kishi, M.; Ogawa, E.; Terada, H.; Ogata, T.; Haruta, H. Sensitivity and specificity of metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial accumulation in the diagnosis of Lewy body diseases in a movement disorder clinic. Park. Relat. Disord. 2011, 17, 395–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treglia, G.; Cason, E.; Stefanelli, A.; Cocciolillo, F.; Di Giuda, D.; Fagioli, G.; Giordano, A. MIBG scintigraphy in differential diagnosis of Parkinsonism: A meta-analysis. Clin. Auton. Res. 2012, 22, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Miyamoto, M.; Inoue, Y.; Usui, Y.; Suzuki, K.; Hirata, K. Reduced cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2006, 67, 2236–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashihara, K.; Imamura, T.; Shinya, T. Cardiac 123I-MIBG uptake is reduced more markedly in patients with REM sleep behavior disorder than in those with early stage Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2010, 16, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, S.; Hirao, K.; Kanetaka, H.; Namioka, N.; Hatanaka, H.; Hirose, D.; Fukasawa, R.; Umahara, T.; Sakurai, H.; Hanyu, H. Utility of the combination of DAT SPECT and MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in differentiating dementia with Lewy bodies. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2016, 43, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saiki, S.; Hirose, G.; Sakai, K.; Kataoka, S.; Hori, A.; Saiki, M.; Kaito, M.; Higashi, K.; Taki, S.; Kakeshita, K. Cardiac 123I-MIBG scintigraphy can assess the disease severity and phenotype of PD. J. Neurol. Sci. 2004, 220, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fereshtehnejad, S.M.; Lokk, J. Orthostatic hypotension in patients with Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonism. Park. Dis. 2014, 2014, 475854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braune, S.; Reinhardt, M.; Schnitzer, R.; Riedel, A.; Lucking, C.H. Cardiac uptake of [123I]MIBG separates Parkinson’s disease from multiple system atrophy. Neurology 1999, 53, 1020–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, M.J.; Jungling, F.D.; Krause, T.M.; Braune, S. Scintigraphic differentiation between two forms of primary dysautonomia early after onset of autonomic dysfunction: Value of cardiac and pulmonary iodine-123 MIBG uptake. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. 2000, 27, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berganzo, K.; Tijero, B.; Somme, J.H.; Llorens, V.; Sanchez-Manso, J.C.; Low, D.; Iodice, V.; Vichayanrat, E.; Mathias, C.J.; Lezcano, E. SCOPA-AUT scale in different parkinsonisms and its correlation with (123)I-MIBG cardiac scintigraphy. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meles, S.K.; Teune, L.K.; Jong, B.M.; de Dierckx, R.A.; Leenders, K.L. Metabolic imaging in Parkinson disease. J. Nucl. Med. 2017, 58, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watabe, T.; Hatazawa, J. Evaluation of functional connectivity in the brain using positron emission tomography: A mini-review. Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyatigorskaya, N.; Gallea, C.; Garcia-Lorenzo, D.; Vidailhet, M.; Lehericy, S. A review of the use of magnetic resonance imaging in Parkinson’s disease. Ther. Adv. Neurol. Disord. 2014, 7, 206–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, D.M.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Løkkegaard, A.; Siebner, H.R. Functional neuroimaging of motor control in Parkinson’s disease: A meta-analysis. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2014, 35, 3227–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingarten, C.P.; Sundman, M.H.; Hickey, P.; Chen, N. Neuroimaging of Parkinson’s disease: Expanding views. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 59, 16–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reivich, M.; Kuhl, D.; Wolf, A.; Greenberg, J.; Phelps, M.A.; Ido, T.; Casella, V.; Fowler, J.; Hoffman, E.; Alavi, A.; et al. The [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization in man. Circ. Res. 1979, 44, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Eidelberg, D.; Ma, Y. Brain network markers of abnormal cerebral glucose metabolism and blood flow in Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2014, 30, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Wang, B.; Liang, W.; Cheng, S.; Wang, B.; Cui, M.; Shou, J. Accuracy of 18F-FDG PET Imaging in Differentiating Parkinson’s Disease from Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Acad. Radiol. 2024, 31, 4575–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujishiro, H.; Iseki, E.; Murayama, N.; Yamamoto, R.; Higashi, S.; Kasanuki, K.; Suzuki, M.; Arai, H.; Sato, K. Diffuse occipital hypometabolism on [18F]-FDG PET scans in patients with idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder: Prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies? Psychogeriatrics 2010, 10, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishiro, H.; Iseki, E.; Kasanuki, K.; Chiba, Y.; Ota, K.; Murayama, N.; Sato, K. A follow-up study of non-demented patients with primary visual cortical hypometabolism: Prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. J. Neurol. Sci. 2013, 334, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carli, G.; Caminiti, S.P.; Galbiati, A.; Marelli, S.; Casoni, F.; Padovani, A.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Perani, D. In-vivo signatures of neurodegeneration in isolated rapid eye movement sleep behaviour disorder. Eur. J. Neurol. 2020, 27, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, G.; Meles, S.K.; Reesink, F.E.; de Jong, B.M.; Pilotto, A.; Padovani, A.; Galbiati, A.; Ferini-Strambi, L.; Leenders, K.L.; Perani, D. Comparison of univariate and multivariate analyses for brain [18F]FDG PET data in α-synucleinopathies. Neuroimage Clin. 2023, 39, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liguori, C.; Ruffini, R.; Olivola, E.; Chiaravalloti, A.; Izzi, F.; Stefani, A.; Pierantozzi, M.; Mercuri, N.B.; Modugno, N.; Centonze, D.; et al. Cerebral glucose metabolism in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder is different from tau-related and α-synuclein-related neurodegenerative disorders: A brain [18F]FDG PET study. Park. Relat. Disord. 2019, 64, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, H.; Yoon, E.J.; Shin, J.H.; Yoo, D.; Nam, H.; Jeon, B. Longitudinal changes in isolated rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder-related metabolic pattern expression. Mov. Disord. 2021, 36, 1889–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang-Vu, T.T.; Gagnon, J.F.; Vendette, M.; Soucy, J.P.; Postuma, R.B.; Montplaisir, J. Hippocampal perfusion predicts impending neurodegeneration in REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology 2012, 79, 2302–2306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, P.; Ayton, S.; Finkelstein, D.I.; Adlard, P.A.; Masters, C.L.; Bush, A.I. Tau protein: Relevance to Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2010, 42, 1775–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.W.; Aarsland, D.; Ffytche, D.; Taddei, R.N.; van Wamelen, D.J.; Wan, Y.M.; Tan, E.K.; Ray Chaudhuri, K.R.; Kings Parcog Group; MDS Nonmotor Study Group. Amyloid-β and Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. 2019, 266, 2605–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzuegbunam, B.C.; Librizzi, D.; Hooshyar, Y.B. PET radiopharmaceuticals for Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease diagnosis, the current and future landscape. Molecules 2020, 25, 977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, H.; Politis, M.; Rabiner, E.A.; Middleton, L.T. Novel PET biomarkers to disentangle molecular pathways across age-related neurodegenerative diseases. Cells 2020, 9, 2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winer, J.R.; Maass, A.; Pressman, P.; Stiver, J.; Schonhaut, D.R.; Baker, S.L.; Baker, S.L.; Kramer, J.; Rabinovici, G.D.; Jagust, W.J. Associations between tau, β-amyloid, and cognition in Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol. 2018, 75, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihaescu, A.S.; Valli, M.; Uribe, C.; Diez-Cirarda, M.; Masellis, M.; Graff-Guerrero, A.; Strafella, A.P. Beta amyloid deposition and cognitive decline in Parkinson’s disease: A study of the PPMI cohort. Mol. Brain 2022, 15, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovalekic, A.; Koglin, N.; Mueller, A.; Stephens, A.W. New protein deposition tracers in the pipeline. EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2017, 1, 11, Erratum in EJNMMI Radiopharm. Chem. 2018, 3, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41181-018-0049-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaghy, P.; Thomas, A.J.; O’Brien, J.T. Amyloid PET Imaging in Lewy body disorders. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2015, 23, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, U.; Lang, A.E.; Masellis, M. Neuroimaging advances in Parkinson’s disease and atypical parkinsonian syndromes. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 572976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edison, P.; Rowe, C.C.; Rinne, J.O.; Ng, S.; Ahmed, I.; Kemppainen, N.; Villemagne, V.L.; O’Keefe, G.; Någren, K.; Chaudhury, K.R.; et al. Amyloid load in Parkinson’s disease dementia and Lewy body dementia measured with [11C]PIB positron emission tomography. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2008, 79, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jie, C.V.M.L.; Treyer, V.; Schibli, R.; Mu, L. Tauvid™: The First FDA-Approved PET Tracer for Imaging Tau Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schonhaut, D.R.; McMillan, C.T.; Spina, S.; Dickerson, B.C.; Siderowf, A.; Devous, M.D.; Tsai, R.; Winer, J.; Russell, D.S.; Litvan, I. 18 F-flortaucipir tau positron emission tomography distinguishes established progressive supranuclear palsy from controls and Parkinson disease: A multicenter study. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 622–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepe, V.; Bordelon, Y.; Boxer, A.; Huang, S.C.; Liu, J.; Thiede, F.C.; Mazziotta, J.C.; Mendez, M.F.; Donoghue, N.; Small, G.W.; et al. PET imaging of neuropathology in tauopathies: Progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2013, 36, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, P.; Gagliardo, C.; La Tona, G.; Bruno, E.; D’angelo, C.; Marrale, M.; Del Poggio, A.; Malaguti, M.C.; Geraci, L.; Baschi, R.; et al. Imaging of Substantia Nigra in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchida, Y.; Kan, H.; Sakurai, K.; Arai, N.; Kato, D.; Kawashima, S.; Ueki, Y.; Matsukawa, N. Voxel-based quantitative susceptibility mapping in Parkinson’s disease with mild cognitive impairment. Mov. Disord. 2019, 34, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmich, R.C.; Vaillancourt, D.E.; Brooks, D.J. The future of brain imaging in Parkinson’s disease. J. Park. Dis. 2018, 8 (Suppl. 1), S47–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberling, J.L.; Dave, K.D.; Frasier, M.A. α-synuclein imaging: A critical need for Parkinson’s disease research. J. Park. Dis. 2013, 3, 565–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzbauer, P.T.; Tu, Z.; Mach, R.H. Current status of the development of PET radiotracers for imaging alpha synuclein aggregates in Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites. Clin. Transl. Imaging 2017, 5, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.L.; Hsieh, C.J.; Guarino, D.S.; Graham, T.J.A.; Lengyel-Zhand, Z.; Schmitz, A.; Chia, W.K.; Young, A.J.; Crosby, J.G.; Plakas, K.; et al. The development of a PET radiotracer for imaging alpha synuclein aggregates in Parkinson’s disease. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 2743–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xiang, J.; Ye, K.; Zhang, Z. Development of Positron Emission Tomography Radiotracers for Imaging α-Synuclein Aggregates. Cells 2025, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capotosti, F. α-synuclein PET Imaging: From Clinical Utility in Multiple System Atrophy to the Possible Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Cells 2025, 14, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathis, C.A.; Lopresti, B.J.; Ikonomovic, M.D.; Klunk, W.E. Small-molecule PET Tracers for Imaging Proteinopathies. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2017, 47, 553–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.; Seibyl, J.; Cartier, A.; Bhatt, R.; Catafau, A.M. Molecular Imaging Insights into Neurodegeneration: Focus on α-Synuclein Radiotracers. J. Nucl. Med. 2014, 55, 1397–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serpell, L.C.; Berriman, J.; Jakes, R.; Goedert, M.; Crowther, R.A. Fiber diffraction of synthetic α-synuclein filaments shows amyloid-like cross-β conformation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 4897–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.P.; Walker, D.E.; Goldstein, J.M.; de Laat, R.; Banducci, K.; Caccavello, R.J.; Barbour, R.; Huang, J.; Kling, K.; Lee, M.; et al. Phosphorylation of Ser-129 is the dominant pathological modification of α-synuclein in familial and sporadic Lewy body disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 29739–29752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalgunov, V.; Xiong, M.; L’Estrade, E.T.; Raval, N.R.; Andersen, I.V.; Edgar, F.G.; Speth, N.R.; Baerentzen, S.L.; Hansen, H.D.; Donovan, L.L.; et al. Blocking of efflux transporters in rats improves translational validation of brain radioligands. EJNMMI Res. 2020, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saturnino Guarino, D.; Miranda Azpiazu, P.; Sunnemark, D.; Elmore, C.S.; Bergare, J.; Artelsmair, M.; Nordvall, G.; Forsberg Morén, A.; Jia, Z.; Cortes-Gonzalez, M.; et al. Identification and In Vitro and In Vivo Characterization of KAC-50.1 as a Potential α-Synuclein PET Radioligand. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2024, 15, 4210–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korat, Š.; Bidesi, N.S.R.; Bonanno, F.; Di Nanni, A.; Hoàng, A.N.N.; Herfert, K.; Maurer, A.; Battisti, U.M.; Bowden, G.D.; Thonon, D.; et al. Alpha-synuclein PET tracer development—An overview about current efforts. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.J.; Ferrie, J.J.; Xu, K.; Lee, I.; Graham, T.J.A.; Tu, Z.; Yu, J.; Dhavale, D.; Kotzbauer, P.; Petersson, E.J.; et al. Alpha-synuclein fibrils contain multiple binding sites for small molecules. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2018, 9, 2521–2527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, D.P.; Yu, L.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Xu, J.; Mach, R.H.; Tu, Z.; Kotzbauer, P.T. Binding of the radioligand SIL23 to α-synuclein fibrils in Parkinson disease brain tissue establishes feasibility and screening approaches for developing a Parkinson disease imaging agent. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.; Zhou, D.; Gaba, V.; Liu, J.; Li, S.; Peng, X.; Xu, J.; Dhavale, D.; Bagchi, D.P.; d’Avignon, A.; et al. Design, synthesis, and characterization of 3-(benzylidene)indolin-2-one derivatives as ligands for α-synuclein fibrils. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 6002–6017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ono, M.; Doi, Y.; Watanabe, H.; Ihara, M.; Ozaki, A.; Saji, H. Structure–activity relationships of radioiodinated diphenyl derivatives with different conjugated double bonds as ligands for α-synuclein aggregates. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 44305–44312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuebler, L.; Buss, S.; Leonov, A.; Ryazanov, S.; Schmidt, F.; Maurer, A.; Weckbecker, D.; Landau, A.M.; Lillethorup, T.P.; Bleher, D.; et al. [11C]MODAG-001—Towards a PET tracer targeting α-synuclein aggregates. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 1759–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arima, K.; Uéda, K.; Sunohara, N.; Hirai, S.; Izumiyama, Y.; Tonozuka-Uehara, H.; Kawai, M. Immunoelectron-microscopic demonstration of NACP/α-synuclein-epitopes on the filamentous component of Lewy bodies in Parkinson’s disease and in dementia with Lewy bodies. Brain Res. 1998, 808, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakabayashi, K.; Yoshimoto, M.; Tsuji, S.; Takahashi, H. Alpha-synuclein immunoreactivity in glial cytoplasmic inclusions in multiple system atrophy. Neurosci. Lett. 1998, 249, 180–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweighauser, M.; Shi, Y.; Tarutani, A.; Kametani, F.; Murzin, A.G.; Ghetti, B.; Matsubara, T.; Tomita, T.; Ando, T.; Hasegawa, K.; et al. Structures of α-synuclein filaments from multiple system atrophy. Nature 2020, 585, 464–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Schweighauser, M.; Zhang, X.; Kotecha, A.; Murzin, A.G.; Garringer, H.J.; Cullinane, P.W.; Saito, Y.; Foroud, T.; et al. Structures of α-synuclein filaments from human brains with Lewy pathology. Nature 2022, 610, 791–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachiller, S.; Jiménez-Ferrer, I.; Paulus, A.; Yang, Y.; Swanberg, M.; Deierborg, T.; Boza-Serrano, A. Microglia in neurological diseases: A road map to brain-disease-dependent inflammatory response. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilarte, T.R. TSPO in diverse CNS pathologies and psychiatric disease: A critical review and a way forward. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 194, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova-Shumkovska, J.; Krstanoski, L.; Veenman, L. Diagnostic and therapeutic potential of TSPO studies regarding neurodegenerative diseases, psychiatric disorders, alcohol use disorders, traumatic brain injury, and stroke: An update. Cells 2020, 9, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhard, A.; Pavese, N.; Hotton, G.; Turkheimer, F.; Es, M.; Hammers, A.; Eggert, K.; Oertel, W.; Banati, R.B.; Brooks, D.J. In vivo imaging of microglial activation with 11C-PK11195 PET in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 2006, 21, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouchi, Y.; Yoshikawa, E.; Sekine, Y.; Futatsubashi, M.; Kanno, T.; Ogusu, T.; Torizuka, T. Microglial activation and dopamine terminal loss in early Parkinson’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2005, 57, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varnäs, K.; Cselényi, Z.; Jucaite, A.; Halldin, C.; Svenningsson, P.; Farde, L.; Varrone, A. PET imaging of [11C]PBR28 in Parkinson’s disease patients does not indicate increased binding to TSPO despite reduced dopamine transporter binding. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2019, 46, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghadery, C.; Koshimori, Y.; Coakeley, S.; Harris, M.; Rusjan, P.; Kim, J.; Houle, S.; Strafella, A.P. Microglial activation in Parkinson’s disease using [18F]FEPPA. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.R.; Yeo, A.J.; Gunn, R.N.; Song, K.; Wadsworth, G.; Lewis, A.; Rhodes, C.; Pulford, D.J.; Bennacef, I.; Parker, C.A.; et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2012, 32, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzamko, N. Cytokine activity in Parkinson’s disease. Neuronal Signal. 2023, 7, NS20220063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilarte, T.R.; Rodichkin, A.N.; McGlothan, J.L.; Acanda De La Rocha, A.M.; Azzam, D.J. Imaging neuroinflammation with TSPO: A new perspective on the cellular sources and subcellular localization. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 234, 108048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endo, H.; Ono, M.; Takado, Y.; Matsuoka, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tagai, K.; Kataoka, Y.; Hirata, K.; Takahata, K.; Seki, C.; et al. Imaging α-synuclein pathologies in animal models and patients with Parkinson’s and related diseases. Neuron 2024, 112, 2540–2557.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, K.; Ono, M.; Takado, Y.; Hirata, K.; Endo, H.; Ohfusa, T.; Kojima, T.; Yamamoto, T.; Onishi, T.; Orihara, A.; et al. High-contrast imaging of alpha-synuclein pathologies in living patients with multiple system atrophy. Mov. Disord. 2022, 37, 2159–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiang, J.; Tao, Y.; Xia, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Q.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Sun, Y.; Xia, W.; Zhang, M.; et al. Development of an α-synuclein positron emission tomography tracer for imaging synucleinopathies. Cell 2023, 186, 3350–3367.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capotosti, F.; Vokali, E.; Molette, J.; Ravache, M.; Delgado, C.; Kocher, J.; Pittet, L.; Vallet, C.; Serra, A.M.; Piorkowska, K.; et al. Discovery of [18F]ACI-12589, a Novel and Promising PET-Tracer for Alpha-Synuclein. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2022, 18, e064680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Capotosti, F.; Schain, M.; Ohlsson, T.; Vokali, E.; Molette, J.; Touilloux, T.; Hliva, V.; Dimitrakopoulos, I.K.; Puschmann, A.; et al. The alpha-synuclein PET tracer [18F] ACI-12589 distinguishes multiple system atrophy from other neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Chia, W.K.; Hsieh, C.J.; Saturnino Guarino, D.; Graham, T.J.A.; Lengyel-Zhand, Z.; Schneider, M.; Tomita, C.; Lougee, M.G.; Kim, H.J.; et al. A Novel Brain PET Radiotracer for Imaging Alpha Synuclein Fibrils in Multiple System Atrophy. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 12185–12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, B.H.; Uzuegbunam, B.; Bagheri, S.; Li, J.; Paslawski, W.; Svenningsson, P.; Agren, H.; Arzberger, T.; Luster, M.; Weber, W.; et al. Novel α-Synuclein Fibrils PET tracers in PFF Mouse Model of Parkinson’s Diease. Nuklearmedizin 2024, 63, 117–118. [Google Scholar]

- Frigerio, I.; Bouwman, M.M.A.; Noordermeer, R.T.G.M.M.; Podobnik, E.; Popovic, M.; Timmermans, E.; Rozemuller, A.J.M.; van de Berg, W.D.J.; Jonkman, L.E. Regional differences in synaptic degeneration are linked to alpha-synuclein burden and axonal damage in Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2024, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Worhunsky, P.; Liu, Q.; Guo, X.; Chen, X.; Sun, H.; Zhang, J.; Toyonaga, T.; Mecca, A.P.; O’Dell, R.S.; et al. Generating synthetic brain PET images of synaptic density based on MR T1 images using deep learning. EJNMMI Phys. 2025, 12, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snellman, A.; Tuisku, J.; Koivumäki, M.; Wahlroos, S.; Aarnio, R.; Rajander, J.; Karrasch, M.; Ekblad, L.L.; Rinne, J.O. SV2A PET shows hippocampal synaptic loss in cognitively unimpaired APOE ε4/ε4 homozygotes. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 20, 8802–8813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Imaging Modality | Idiopathic Parkinson’s Disease (PD) | Multiple System Atrophy (MSA) | Progressive Supranuclear Palsy (PSP) | Corticobasal Degeneration (CBD) | Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DAT SPECT/PET | Asymmetric posterolateral putaminal reduction; | Marked, symmetric putaminal loss; | Marked caudate + putamen loss; less asymmetry; | Asymmetric contralateral reduction; | Reduced uptake similar to PD more symmetric; |

| [^18F]FDOPA PET | Decreased putaminal uptake; | Severe, symmetric putaminal + caudate reduction; | Widespread striatal loss; | Asymmetric reductions; | Reduced, but less specific for DLB; |

| Cardiac MIBG Scintigraphy | Markedly reduced H/M ratio; | Typically normal or mildly reduced; | Normal; | Normal; | Markedly reduced, similar to PD; |

| FDG PET | Hypermetabolism in pallidothalamic + cerebellar networks, | Cerebello-pontine/putaminal hypometabolism; | Frontal + midbrain hypometabolism; | Asymmetric frontoparietal hypometabolism; | Occipital hypometabolism characteristic; |

| Target | Imaging Modality | Radiotracer | Clinical Role | Stage | Developmental Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VMAT2 | PET | [^11C]DTBZ [^18F]AV-133; | Presynaptic density | C/R | FDA/EMA-approved tracers in use; others in clinical validation; |

| Post-synaptic D2/3 receptors | PET/SPECT | [^11C]raclopride [^123I]IBZM [^18F]fallypride; | Differentiation PD vs. Atypical Parkinsonism, | C/R | Mostly established tracers; high-affinity D3-selective agents under development; |

| Tau protein | PET | [^18F]AV1451, [^18F]FDDNP | Differentiation of PSP, CBD, DLB | R | Second-generation tau tracers in early clinical testing; |

| TSPO | PET | [^11C]PK11195, [^11C]PBR28 [^18F]FEPPA | Assessment of microglial activation | R | Several second-generation TSPO ligands in clinical research; no approved clinical use; |

| α-Syn | PET | [^11C]MODAG-001, [^11C]anle253, IDP-4; | Imaging of α-Syn aggregates | Pre-C | All α-Syn tracers remain preclinical; first-in-human studies ongoing or planned; |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martini, A.L.; Sestini, S.; Guarino, D.S.; Feraco, P. Nuclear Medicine Imaging Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future Directions. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040308

Martini AL, Sestini S, Guarino DS, Feraco P. Nuclear Medicine Imaging Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future Directions. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):308. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040308

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartini, Anna Lisa, Stelvio Sestini, Dinahlee Saturnino Guarino, and Paola Feraco. 2025. "Nuclear Medicine Imaging Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future Directions" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040308

APA StyleMartini, A. L., Sestini, S., Guarino, D. S., & Feraco, P. (2025). Nuclear Medicine Imaging Biomarkers in Parkinson’s Disease: Past, Present, and Future Directions. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 308. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040308