Cytokine Profiles and Inflammatory Implications in Chagas Disease: Associations with Ventricular Function and Conduction Disorders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Perez-Molina, J.A.; Molina, I. Chagas disease. Lancet 2018, 391, 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Chagas Disease (Also Known as American Trypanosomiasis). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chagas-disease-(american-trypanosomiasis) (accessed on 6 November 2023).

- Moncayo, A. Chagas disease: Current epidemiological trends after the interruption of vectorial and transfusional transmission in the Southern Cone countries. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kölliker-Frers, R.A.; Otero-Losada, M.; Razzitte, G.; Calvo, M.; Carbajales, J.; Capani, F. Chagas Cardiomyopathy: Role of Sustained Host-Parasite Interaction in Systemic Inflammatory Burden. In Chagas Disease: Basic Investigations and Challenges; Books on Demand: Norderstedt, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury, I.H.; Koo, S.-J.; Gupta, S.; Liang, L.Y.; Bahar, B.; Silla, L.; Nuñez-Burgos, J.; Barrientos, N.; Zago, M.P.; Garg, N.J. Gene Expression Profiling and Functional Characterization of Macrophages in Response to Circulatory Microparticles Produced during Trypanosoma cruzi Infection and Chagas Disease. J. Innate Immun. 2017, 9, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronemberger-Andrade, A.; Xander, P.; Soares, R.P.; Pessoa, N.L.; Campos, M.A.; Ellis, C.C.; Grajeda, B.; Ofir-Birin, Y.; Almeida, I.C.; Regev-Rudzki, N.; et al. Trypanosoma cruzi-Infected Human Macrophages Shed Proinflammatory Extracellular Vesicles That Enhance Host-Cell Invasion via Toll-Like Receptor 2. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.B.R.; dos Reis, M.A.; Romano, A.; Pereira, S.A.d.L.; Teixeira, V.d.P.A.; Junior, S.T.; Rodrigues, V. In situ expression of regulatory cytokines by heart inflammatory cells in chagas’ disease patients with heart failure. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2020, 2012, 361730. [Google Scholar]

- Paolucci, A.G.; Krishnan, D.; Principato, M.B.; Von-Wulffen, M.A.; Carbajales, J.; Baranchuk, A. Lack of correlation for anti-β1 auto-antibodies and cardioelectric disorders in chagas cardiomyopathy. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2023, 93, 260–262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carbajales, J.; Krishnan, D.; Principato, M.; Tomatti, A.; Paolucci, A.; Yoo, H.S.; von Wulffen, A.; Ciampi, N.; Tepper, R.; Carradori, J.; et al. Prevalence of Cardiac Arrhythmias and Distal Conduction Disorders in Patients with Chronic Chagas’ Disease and Elevated Autoantibodies Against M2 Muscarinic Acetylcholine Receptors. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2021, 46, 100820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Takahashi, T. Interleukin-6 and Cardiovascular Diseases. Jpn. Heart J. 2004, 45, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, Y.; Takatsu, Y.; Kataoka, K.; Yamada, T.; Taniguchi, R.; Sasayama, S.; Matsumori, A. Serial circulating concentrations of c-reactive protein, interleukin (IL)-4, and IL-6 in patients with acute left heart decompensation. Clin. Cardiol. 1999, 22, 811–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petretta, M.; Condorelli, G.L.; Spinelli, L.; Scopacasa, F.; de Caterina, M.; Leosco, D.; Vicario, M.L.; Bonaduce, D. Circulating levels of cytokines and their site of production in patients with mild to severe chronic heart failure. Am. Heart J. 2000, 140, 12A–18A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguy, A.; Le Bouter, S.; Comtois, P.; Chartier, D.; Villeneuve, L.; Wakili, R.; Nishida, K.; Nattel, S. Ion channel subunit expression changes in cardiac Purkinje fibers: A potential role in conduction abnormalities associated with congestive heart failure. Circ. Res. 2009, 104, 1113–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roman-Campos, D.; Marin-Neto, J.A.; Santos-Miranda, A.; Kong, N.; D’Avila, A.; Rassi, A., Jr. Arrhythmogenic Manifestations of Chagas Disease: Perspectives from the Bench to Bedside. Circ. Res. 2024, 134, 1379–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.C.; Masuda, M.O.; Tanowitz, H.B.; Wittner, M.; Goldenberg, R.C.; Spray, D.C. Conduction defects and arrhythmias in Chagas’ disease: Possible role of gap junctions and humoral mechanisms. J. Cardiovasc. Electrophysiol. 1994, 5, 686–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, G.R.; Gomes, J.A.S.; Fares, R.C.G.; Damásio, M.P.d.S.; Chaves, A.T.; Ferreira, K.S.; Nunes, M.C.P.; Medeiros, N.I.; Valente, V.A.A.; Corrêa-Oliveira, R.; et al. Plasma Cytokine Expression Is Associated with Cardiac Morbidity in Chagas Disease. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e87082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Principato, M.B.; Paolucci, A.; Miranda, S.; Lombardi, M.G.; Sosa, G.; Von Wulffen, M.A.; Villafernández, R.O.C.Í.O.; Tomatti, A.; Di Girolamo, G.; Carbajales, J. Asociación entre interleuquinas inflamatorias y la presencia de trastornos intra-ventriculares de la conducción en pacientes con serología positiva para enfermedad de Chagas y función ventricular conservada. Rev. Argent. Cardiol. 2021, 89, 130–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.A.S.; Bahia-Oliveira, L.M.G.; Rocha, M.O.C.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Gazzinelli, G.; Correa-Oliveira, R. Evidence that development of severe cardiomyopathy in human Chagas’ disease is due to a Th1-specific immune response. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 1185–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, W.O.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Cançado, J.R.; Pinto-Dias, J.C.; Brener, Z.; Freeman Júnior, G.L.; Colley, D.G.; Gazzinelli, G.; Parra, J.C. Activated T and B lymphocytes in peripheral blood of patients with Chagas’ disease. Int. Immunol. 1994, 6, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morillo, C.A.; Marin-Neto, J.A.; Avezum, A.; Sosa-Estani, S.; Rassi, A., Jr.; Rosas, F.; Villena, E.; Quiroz, R.; Bonilla, R.; Britto, C.; et al. Randomized Trial of Benznidazole for Chronic Chagas’ Cardiomyopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.D.; Jones, E.M.; Tostes, S.; Lopes, E.R.; Chapadeiro, E.; Gazzinelli, G.; Colley, D.G.; McCurley, T.L. Expression of major histocompatibility complex antigens and adhesion molecules in hearts of patients with chronic Chagas’ disease. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1993, 49, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.; Arai, K.; Giménez, E.; Jiménez, M.; Pascuzo, C.; Rodríguez-Bonfante, C.; Bonfante-Cabarcas, R. C-Reactive Protein and Interleukin-6 Serum Levels Increase as Chagas Disease Progresses Towards Cardiac Failure. Rev. Española Cardiol. 2006, 59, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedacko, J.; Singh, R.B.; Gupta, A.; Hristova, K.; Toda, E.; Kumar, A.; Saxena, M.; Baby, A.; Singh, R.; Toru, T.; et al. Inflammatory mediators in chronic heart failure in North India. Acta Cardiol. 2014, 69, 391–398. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, L.C.; Rizzo, L.V.; Ianni, B.; Albuquerque, F.; Bacal, F.; Carrara, D.; Bocchi, E.A.; Teixeira, H.C.; Mady, C.; Kalil, J.; et al. Chronic Chagas’ disease cardiomyopathy patients display an increased IFN-γ response to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Autoimmun. 2001, 17, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, J.P.S.; Andrieux, P.; Brochet, P.; Almeida, R.R.; Kitano, E.; Honda, A.K.; Iwai, L.K.; Andrade-Silva, D.; Goudenège, D.; Silva, K.D.A.; et al. Co-Exposure of Cardiomyocytes to IFN-γ and TNF-α Induces Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Nitro-Oxidative Stress: Implications for the Pathogenesis of Chronic Chagas Disease Cardiomyopathy. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 755862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorena, V.M.B.; Lorena, I.M.B.; Braz, S.C.M.; Melo, A.S.; Melo, M.F.A.D.; Melo, M.G.A.C.; Silva, E.D.; Ferreira, A.G.P.; Morais, C.N.L.; Costa, V.M.A.; et al. Cytokine levels in serious cardiopathy of chagas disease after in vitro stimulation with recombinant antigens from Trypanosoma cruzi. Scand. J. Immunol. 2010, 72, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laucella, S.A.; Postan, M.; Martin, D.; Fralish, B.H.; Albareda, M.C.; Alvarez, M.G.; Lococo, B.; Barbieri, G.; Viotti, R.J.; Tarleton, R.L. Frequency of interferon-γ-producing T cells specific for Trypanosoma cruzi inversely correlates with disease severity in chronic human Chagas disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2004, 189, 909–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Melo, A.S.; de Lorena, V.M.B.; de Moura Braz, S.C.; Docena, C.; de Miranda Gomes, Y. IL-10 and IFN-γ gene expression in chronic Chagas disease patients after in vitro stimulation with recombinant antigens of Trypanosoma cruzi. Cytokine 2012, 58, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tucholski, T.; Cai, W.; Gregorich, Z.R.; Bayne, E.F.; Mitchell, S.D.; McIlwain, S.J.; de Lange, W.J.; Wrobbel, M.; Karp, H.; Hite, Z.; et al. Distinct hypertrophic cardiomyopathy genotypes result in convergent sarcomeric proteoform profiles revealed by top-down proteomics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24691–24700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grison, M.; Merkel, U.; Kostan, J.; Djinović-Carugo, K.; Rief, M. α-Actinin/titin interaction: A dynamic and mechanically stable cluster of bonds in the muscle Z-disk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 1015–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvani, A.; Ribeiro, C.S.; Aliberti, J.C.; Michailowsky, V.; Santos, P.V.; Murta, S.M.; Romanha, A.J.; Almeida, I.C.; Farber, J.; Lannes-Vieira, J.; et al. Kinetics of cytokine gene expression in experimental chagasic cardiomyopathy: Tissue parasitism and endogenous IFN-γ as important determinants of chemokine mRNA expression during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Microbes Infect. 2000, 2, 851–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petray, P.; Corral, R.; Meckert, P.C.; Laguens, R. Role of macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) in macrophage homing in the spleen and heart pathology during experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Acta Trop. 2002, 83, 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, R.C.; Ianni, B.M.; Abel, L.C.; Buck, P.; Mady, C.; Kalil, J.; Cunha-Neto, E. Increased Plasma Levels of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α in Asymptomatic/“Indeterminate” and Chagas Disease Cardiomyopathy Patients. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2003, 98, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talvani, A.; Rocha, M.O.C.; Barcelos, L.S.; Gomes, Y.M.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Teixeira, M.M. Elevated concentrations of CCL2 and tumor necrosis factor-α in chagasic cardiomyopathy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trinchieri, G. Interleukin-12 and the regulation of innate resistance and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2003, 3, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, F.S.; Martins, G.A.; Aliberti, J.C.; Mestriner, F.L.; Cunha, F.Q.; Silva, J.S. Trypanosoma cruzi-infected cardiomyocytes produce chemokines and cytokines that trigger potent nitric oxide-dependent trypanocidal activity. Circulation 2000, 102, 3003–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarleton, R.L. CD8+ T cells in Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Semin. Immunopathol. 2015, 37, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, S.G.; Reis, M.M.; Coelho, V.; Nogueira, L.G.; Monteiro, S.M.; Mairena, E.C.; Bacal, F.; Bocchi, E.; Guilherme, L.; Zheng, X.X.; et al. Locally produced survival cytokines IL-15 and IL-7 may be associated to the predominance of CD8+ T cells at heart lesions of human chronic Chagas disease cardiomyopathy. Scand. J. Immunol. 2007, 66, 362–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta, C.J.; Cuellar, A.; Lasso, P.; Mateus, J.; Gonzalez, J.M. Trypanosoma cruzi-specific CD8+ T cells and other immunological hallmarks in chronic Chagas cardiomyopathy: Two decades of research. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 12, 1075717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffê, E.; Oliveira, F.; Souza, A.L.; Pinho, V.; Souza, D.G.; Souza, P.R.; Russo, R.C.; Santiago, H.C.; Romanha, Á.J.; Tanowitz, H.B.; et al. Role of CCL3/MIP-1alpha and CCL5/RANTES during acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection in rats. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 669–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Gibaldi, D.; Vilar-Pereira, G.; Pereira, I.R.; Silva, A.A.; Barrios, L.C.; Ramos, I.P.; Mata Dos Santos, H.A.; Gazzinelli, R.; Lannes-Vieira, J. CCL3/Macrophage Inflammatory Protein-1alpha Is Dually Involved in Parasite Persistence and Induction of a TNF- and IFNgamma-Enriched Inflammatory Milieu in Trypanosoma cruzi-Induced Chronic Cardiomyopathy. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roffê, E.; Rothfuchs, A.G.; Santiago, H.C.; Marino, A.P.; Ribeiro-Gomes, F.L.; Eckhaus, M.; Antonelli, L.R.; Murphy, P.M. IL-10 limits parasite burden and protects against fatal myocarditis in a mouse model of Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J. Immunol. 2012, 188, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, F.F.; Vitelli-Avelar, D.M.; Teixeira-Carvalho, A.; Antas, P.R.Z.; Gomes, J.A.S.; Sathler-Avelar, R.; Rocha, M.O.C.; Elói-Santos, S.M.; Pinho, R.T.; Correa-Oliveira, R.; et al. Regulatory T cells phenotype in different clinical forms of Chagas’ disease. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| LVEF < 35% (n = 22) | LVEF > 50% (n = 22) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 63.4 (±10.8) | 55.6 (±11.4) |

| Male (n, %) | 15 (68.2%) | 11 (50.0%) |

| Hypertension (n, %) | 18.2 | 3 (13.6%) |

| Type 2 diabetes (n, %) | 1 (4.5%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Dyslipidemia (n, %) | 1 (4.5%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| Atrial fibrillation (n, %) | 3 (13.6%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Stroke (%) | 3 (13.6%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| Blocks, pacemakers and ICD (n, %) | 21 (95.5%) | 12 (55.5%) |

| Pacemaker (n, %) | 2 (9.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| ICD (n, %) | 6 (27.3%) | 1 (4.5%) |

| Arrhythmia (n, %) | 11 (50.0%) | 4 (18.2%) |

| Use of beta blockers (n, %) | 16 (77.3%) | 3 (13.6%) |

| LVEF (mean % ± SD) | 28.8 (±4.4) | 60.9 (±6.7) |

| Cytokine Plasma Level as Median (25th–75th Percentile), in pg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Cytokine | LVEF < 35% n = 22 | LVEF > 50% n = 22 | p |

| TNF-α | 16.479 (12.921–26.561) | 23.886 (17.556–25.942) | 0.189 |

| IL 6 | 1.085 (0.316–3.359) | 3.692 (0.256–6.244) | 0.145 |

| MCP-1 | 186.942 (144.672–249.276) | 186.646 (142.071–207.473) | 0.481 |

| IL-10 | 19.42 (6.602–25.988) | 17.792 (3.292–24.775) | 0.607 |

| MIP1α | 6.921 (2.091–9.201) | 8.236 (0.603–11.135) | 0.864 |

| IL-12 p70 | 9.84 (7.19–13.204) | 9.785 (5.422–11.712) | 0.642 |

| IL2 | 2.394 (2.041–2.897) | 2.795 (1.763–3.453) | 0.481 |

| IL-1β | 2.04 (1.324–2.688) | 2.034 (1.148–2.62) | 0.821 |

| IL-15 | 4.018 (2.546–7.256) | 4.636 (2.684–5.595) | 0.724 |

| IL-17A | 4.022 (2.961–5.252) | 3.681 (1.978–5.024) | 0.725 |

| INF-γ | 8.726 (6.396–10.74) | 7.995 (4.311–9.779) | 0.372 |

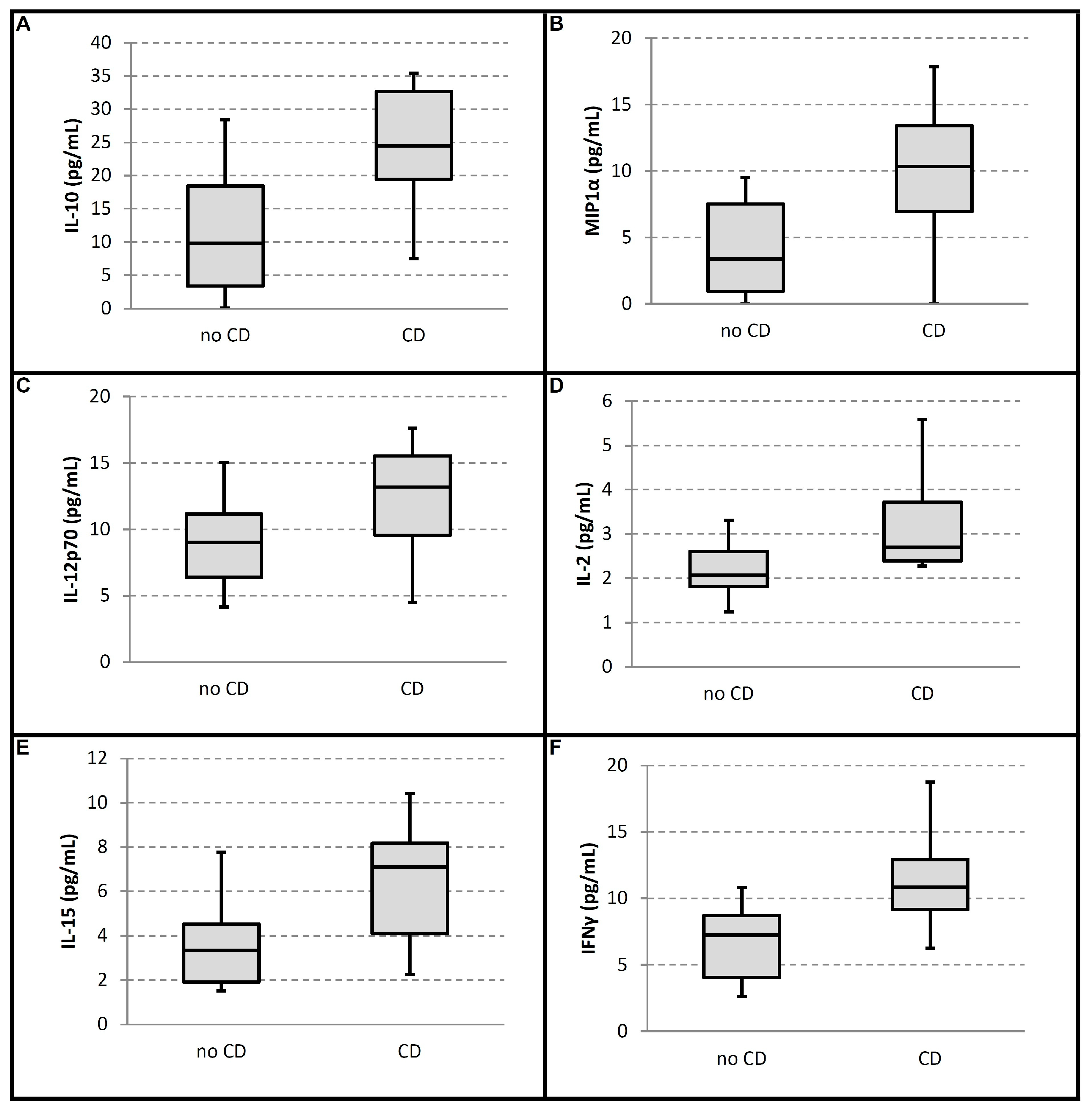

| With CD (Group 1) (n = 10) | Without CD (Group 2) (n = 12) | Hodges–Lehmann Differences (CI 95%) | p | n | q | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients | 10 | 12 | ||||

| AGE (mean %, ±SD, YEARS) | 61.30 ± 13.36 | 50.92 ± 7.10 | 0.107 | |||

| Male (n, %) | 6 (60) | 5 (41.7) | 0.392 | |||

| LVEF (mean %, ±SD) | 59.60 ± 6.28 | 62.00 ± 7.07 | 0.539 | |||

| Cytokine plasma levels (pg/mL) | ||||||

| TNF-α (mean, range) | 7.25 (4.09–8.70) | 10.83 (9.15–12.92) | −3.94 (−8.42 to −1.74) | 0.006 | 1 # | 0.005 |

| IL 6 (mean, range) | 9.83 (3.40–18.44) | 24.49 (19.45–32.64) | −15.90 (−30.45 to −4.03) | 0.008 | 2 # | 0.009 |

| MCP-1 (mean, range) | 3.35 (0.94–7.51) | 10.33 (6.94–13.42) | −6.27 (−11.07 to −0.30) | 0.015 | 3 # | 0.014 |

| IL-10 (mean, range) | 3.36 (1.92–4.51) | 7.09 (4.07–8.18) | −3.12 (−5.30 to −0.28) | 0.02 | 4 # | 0.018 |

| MIP1α (mean, range) | 2.07 (1.81–2.61) | 2.70 (2.39–3.73) | −0.92 (−1.98 to −0.17) | 0.023 | 5 # | 0.023 |

| IL-12 p70 (mean, range) | 9.02 (6.43–11.17) | 13.20 (9.57–15.53) | −4.41 (−8.10 to −0.36) | 0.033 | 6 # | 0.027 |

| IL2 (mean, range) | 0.79 (0.21–1.38) | 3.31 (1.11–5.45) | −2.19 (−4.81 to 0.00) | 0.054 | 7 | 0.032 |

| IL-1β (mean, range) | 14.53 (12.52–19.49) | 22.13 (16.21–28.21) | −4.67 (−13.92 to 1.29) | 0.086 | 8 | 0.036 |

| IL-15 (mean, range) | 3.69 (2.21–4.56) | 4.95 (3.40–6.05) | −1.45 (−2.95 to 0.55) | 0.106 | 9 | 0.041 |

| IL-17A (mean, range) | 1.87 (1.43–2.23) | 2.62 (1.19–3.63) | −0.75 (−1.76 to 0.64) | 0.271 | 10 | 0.045 |

| INF-γ (mean, range) | 186.94 (172.68–226.13) | 194.78 (123.08–330.28) | 2.84 (−150.81 to 76.25) | 1 | 11 | 0.05 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Principato, M.; Carvelli, M.V.; Paolucci, A.G.; Miranda, S.; Keller, G.A.; Lago, M.; Di Girolamo, G.; Carbajales, J. Cytokine Profiles and Inflammatory Implications in Chagas Disease: Associations with Ventricular Function and Conduction Disorders. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040309

Principato M, Carvelli MV, Paolucci AG, Miranda S, Keller GA, Lago M, Di Girolamo G, Carbajales J. Cytokine Profiles and Inflammatory Implications in Chagas Disease: Associations with Ventricular Function and Conduction Disorders. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):309. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040309

Chicago/Turabian StylePrincipato, Mario, Maria Victoria Carvelli, Analia Gladys Paolucci, Silvia Miranda, Guillermo Alberto Keller, Manuel Lago, Guillermo Di Girolamo, and Justo Carbajales. 2025. "Cytokine Profiles and Inflammatory Implications in Chagas Disease: Associations with Ventricular Function and Conduction Disorders" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040309

APA StylePrincipato, M., Carvelli, M. V., Paolucci, A. G., Miranda, S., Keller, G. A., Lago, M., Di Girolamo, G., & Carbajales, J. (2025). Cytokine Profiles and Inflammatory Implications in Chagas Disease: Associations with Ventricular Function and Conduction Disorders. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 309. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040309