Microbiome and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Gut Health and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Heart Failure Progression

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Gut dysbiosis contributes to HF via systemic inflammation and endotoxemia.

- Microbial metabolites, like SCFAs and TMAO, affect cardiac remodeling and function.

- Comorbidities, like obesity and diabetes, exacerbate gut dysbiosis in HF.

- Dietary and probiotic interventions hold potential for microbiome-targeted HF therapies.

2. Methodology

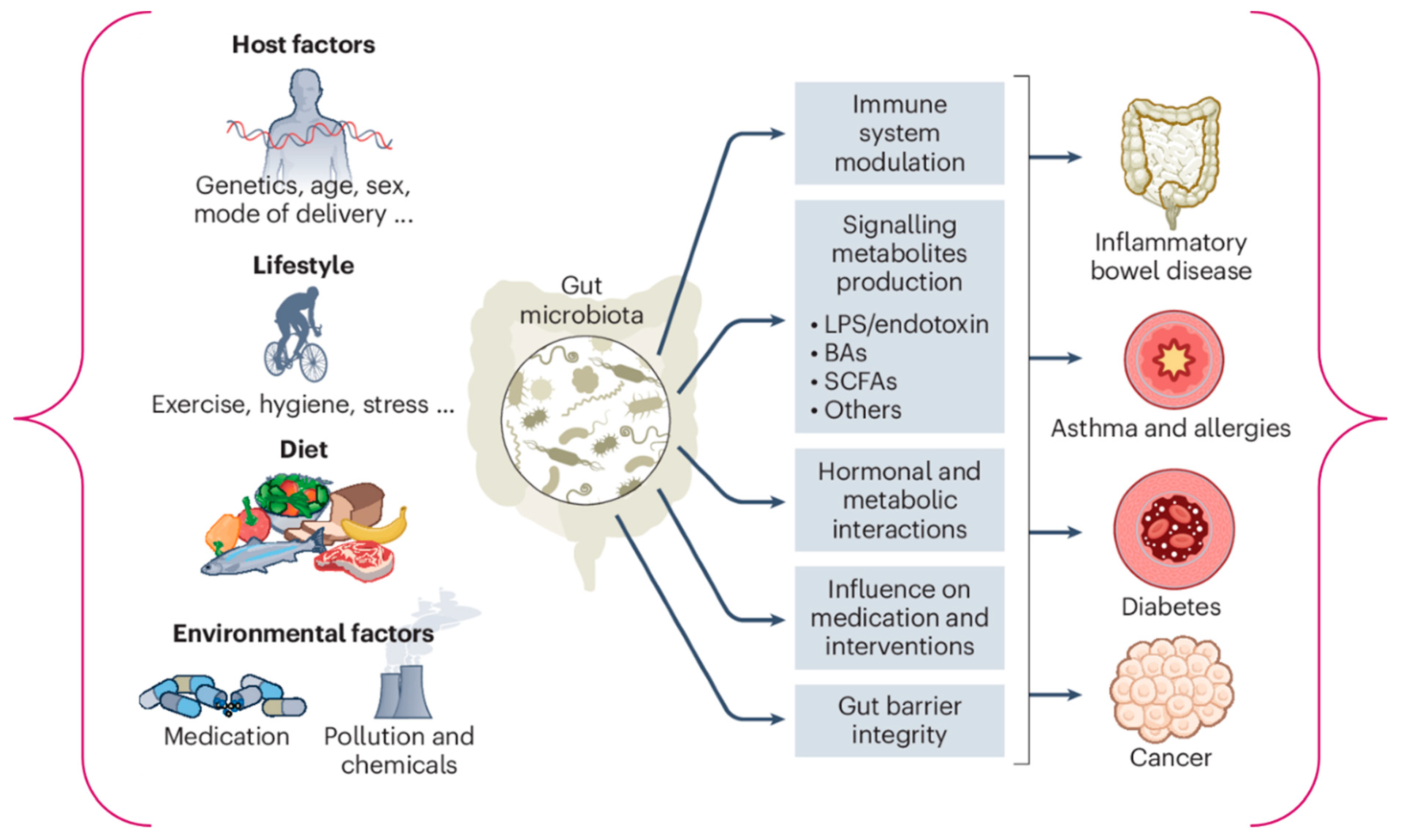

3. Science of the Gut Microbiome: Present Knowledge

3.1. Gut Microbiome: A Tool for Optimizing Heart Failure Therapy

3.2. The Gut Microbiota’s Role in Pathology and Physiology

4. Gut Metabolites Associated with HF

4.1. Short-Chain Fatty Acids: Protective Roles and Mechanisms in HF

4.2. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO): Pro-Inflammatory and Pro-Atherogenic Effects

4.3. Bile Acid

4.4. Phenylacetylglutamine

5. Clinical Evidence Linking the Microbiome to HF

6. Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

6.1. Therapeutic Target

6.2. Dietary Interventions

6.3. Renal Denervation

6.4. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT)

6.5. Areas for Future Research

Longitudinal Studies and Clinical Trials

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HF | Heart Failure |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| TMAO | Trimethylamine-N-oxide |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharides |

| BAs | Bile Acids |

| HIF | Hypoxia-Inducible Factor |

| FMT | Fecal Microbiota Transplantation |

| GPR | G-Protein-Coupled Receptors |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor Kappa B |

| NO | Nitric Oxide |

| NHANES | National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney Disease |

| CVDs | cardiovascular diseases |

| ICIs | Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| HRQL | Health-related quality of life |

| FXR | Farnesoid X Receptor |

| TGR5 | Takeda G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 5 |

| GPCRs | G-Protein-Coupled Receptors |

| ADRs | Adrenergic Receptors |

| PERK | Protein Kinase RNA-Like Endoplasmic Reticulum Kinase |

| QALYs | Quality-Adjusted Life Years |

References

- Guha, S.; Harikrishnan, S.; Ray, S.; Sethi, R.; Ramakrishnan, S.; Banerjee, S.; Bahl, V.; Goswami, K.; Banerjee, A.K.; Shanmugasundaram, S.; et al. CSI position statement on management of heart failure in India. Indian Heart J. 2018, 70, S1–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraen, A.; Duvva, D.; Rao, A. Heart Failure and Cardiac Device Therapy: A Review of Current National Institute of Health and Care Excellence and European Society of Cardiology Guidelines. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol. Rev. 2023, 12, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhammar, A.; Bodegard, J.; Vanderheyden, M.; Tangri, N.; Karasik, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Sveen, K.A.; Taveira-Gomes, T.; Botana, M.; Hunziker, L.; et al. Prevalence, outcomes and costs of a contemporary, multinational population with heart failure. Heart 2023, 109, 548–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groenewegen, A.; Rutten, F.H.; Mosterd, A.; Hoes, A.W. Epidemiology of heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 1342–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragazzi, N.L.; Zhong, W.; Shu, J.; Abu Much, A.; Lotan, D.; Grupper, A.; Younis, A.; Dai, H. Burden of heart failure and underlying causes in 195 countries and territories from 1990 to 2017. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2021, 28, 1682–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seferović, P.M.; Vardas, P.; Jankowska, E.A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Timmis, A.; Milinković, I.; Polovina, M.; Gale, C.P.; Lund, L.H.; Lopatin, Y.; et al. The Heart Failure Association Atlas: Heart Failure Epidemiology and Management Statistics 2019. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2021, 23, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Anderson, C.A.; Arora, P.; Avery, C.L.; Baker-Smith, C.M.; Beaton, A.Z.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2023 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2023, 147, E93–E621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C.W.; Aday, A.W.; Almarzooq, Z.I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A.Z.; Bittencourt, M.S.; Boehme, A.K.; Buxton, A.E.; Carson, A.P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145, E153–E639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, I.; Joseph, P.; Balasubramanian, K.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Lund, L.H.; Ezekowitz, J.A.; Kamath, D.; Alhabib, K.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Budaj, A.; et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Mortality in Heart Failure: The Global Congestive Heart Failure Study of 23 000 Patients From 40 Countries. Circulation 2021, 143, 2129–2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warraich, H.J.; Kitzman, D.W.; Whellan, D.J.; Duncan, P.W.; Mentz, R.J.; Pastva, A.M.; Nelson, M.B.; Upadhya, B.; Reeves, G.R. Physical Function, Frailty, Cognition, Depression, and Quality of Life in Hospitalized Adults ≥60 Years with Acute Decompensated Heart Failure with Preserved Versus Reduced Ejection Fraction. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e005254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Lubetkin, E.I.; Barile, J.P.; Horner-Johnson, W.; DeMichele, K.; Stark, D.S.M.; Zack, M.M.; Thompson, W.W. Quality-adjusted Life Years (QALY) for 15 Chronic Conditions and Combinations of Conditions Among US Adults Aged 65 and Older. Med. Care 2018, 56, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; Al Snih, S.; Markides, K.; Hall, O.; Peterson, M. The burden of health conditions for middle-aged and older adults in the United States: Disability-adjusted life years. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adane, E.; Atnafu, A.; Aschalew, A.Y. The Cost of Illness of Hypertension and Associated Factors at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital Northwest Ethiopia, 2018. Clin. Outcomes Res. 2020, 12, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademi, Z.; Ackerman, I.N.; Zomer, E.; Liew, D. Productivity-Adjusted Life-Years: A New Metric for Quantifying Disease Burden. PharmacoEconomics 2021, 39, 271–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adak, A.; Khan, M.R. An insight into gut microbiota and its functionalities. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2019, 76, 473–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ke, B.; Du, J. TMAO: How gut microbiota contributes to heart failure. Transl. Res. 2021, 228, 109–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhang, H.; Ren, S.; Ding, Y.; Remex, N.S.; Bhuiyan, S.; Qu, J.; Tang, X. Gut microbiota and microbiota-derived metabolites in cardiovascular diseases. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 2269–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, B.; Zhang, K.; Li, Y.; Sun, K. Update on gut microbiota in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 1059349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, D.; Feng, W.; Peng, C. Functions of Gut Microbiota Metabolites, Current Status and Future Perspectives. Aging Dis. 2022, 13, 1106–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duttaroy, A.K. Role of Gut Microbiota and Their Metabolites on Atherosclerosis, Hypertension and Human Blood Platelet Function: A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franzosa, E.A.; Huang, K.; Meadow, J.F.; Gevers, D.; Lemon, K.P.; Bohannan, B.J.M.; Huttenhower, C. Identifying personal microbiomes using metagenomic codes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, E2930–E2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, L.; Goemans, C.V.; Wirbel, J.; Kuhn, M.; Eberl, C.; Pruteanu, M.; Müller, P.; Garcia-Santamarina, S.; Cacace, E.; Zhang, B.; et al. Unravelling the collateral damage of antibiotics on gut bacteria. Nature 2021, 599, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobels, A.; van Marcke, C.; Jordan, B.F.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. The gut microbiome and cancer: From tumorigenesis to therapy. Nat. Metab. 2025, 7, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cluzel, G.L.; Ryan, P.M.; Herisson, F.M.; Caplice, N.M. High-fidelity porcine models of metabolic syndrome: A contemporary synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Metab. 2022, 322, E366–E381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maier, L.; Pruteanu, M.; Kuhn, M.; Zeller, G.; Telzerow, A.; Anderson, E.E.; Brochado, A.R.; Fernandez, K.C.; Dose, H.; Mori, H.; et al. Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 2018, 555, 623–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, M.; Zimmermann-Kogadeeva, M.; Wegmann, R.; Goodman, A.L. Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature 2019, 570, 462–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haiser, H.J.; Gootenberg, D.B.; Chatman, K.; Sirasani, G.; Balskus, E.P.; Turnbaugh, P.J. Predicting and Manipulating Cardiac Drug Inactivation by the Human Gut Bacterium Eggerthella lenta. Science 2013, 341, 295–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routy, B.; Le Chatelier, E.; Derosa, L.; Duong, C.P.M.; Alou, M.T.; Daillère, R.; Fluckiger, A.; Messaoudene, M.; Rauber, C.; Roberti, M.P.; et al. Gut microbiome influences efficacy of PD-1–based immunotherapy against epithelial tumors. Science 2018, 359, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derosa, L.; Routy, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Iebba, V.; Zalcman, G.; Friard, S.; Mazieres, J.; Audigier-Valette, C.; Moro-Sibilot, D.; Goldwasser, F.; et al. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awoyemi, A.; Mayerhofer, C.; Felix, A.S.; Hov, J.R.; Moscavitch, S.D.; Lappegård, K.T.; Hovland, A.; Halvorsen, S.; Halvorsen, B.; Gregersen, I.; et al. Rifaximin or Saccharomyces boulardii in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: Results from the randomized GutHeart trial. EBioMedicine 2021, 70, 103511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Li, R.; Raes, J.; Arumugam, M.; Burgdorf, K.S.; Manichanh, C.; Nielsen, T.; Pons, N.; Levenez, F.; Yamada, T.; et al. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 2010, 464, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, A.; Mitchell, A.L.; Boland, M.; Forster, S.C.; Gloor, G.B.; Tarkowska, A.; Lawley, T.D.; Finn, R.D. A new genomic blueprint of the human gut microbiota. Nature 2019, 568, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Deng, C.; Wang, H.; Tang, X. Acylations in cardiovascular diseases: Advances and perspectives. Chin. Med. J. 2022, 135, 1525–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Chan, A.T.; Sun, J. Influence of the Gut Microbiome, Diet, and Environment on Risk of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.; Weeks, T.L.; Hazen, S.L. Gut Microbiota and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ. Res. 2020, 127, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdes, A.M.; Walter, J.; Segal, E.; Spector, T.D. Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ 2018, 361, k2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Z.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, Z.; Sang, L.; Zhu, J.; Luo, S.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, K.; et al. Intermediate role of gut microbiota in vitamin B nutrition and its influences on human health. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1031502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Branchereau, M.; Burcelin, R.; Heymes, C. The gut microbiome and heart failure: A better gut for a better heart. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2019, 20, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lupu, V.V.; Adam Raileanu, A.; Mihai, C.M.; Morariu, I.D.; Lupu, A.; Starcea, I.M.; Frasinariu, O.E.; Mocanu, A.; Dragan, F.; Fotea, S. The Implication of the Gut Microbiome in Heart Failure. Cells 2023, 12, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trøseid, M.; Andersen, G.Ø.; Broch, K.; Hov, J.R. The gut microbiome in coronary artery disease and heart failure: Current knowledge and future directions. EBioMedicine 2020, 52, 102649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, H.-Y.; Hu, X.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.-Y. Current understanding of gut microbiota alterations and related therapeutic intervention strategies in heart failure. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1843–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q.; Li, H.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, A.; Xie, Y.; Li, Y.; Lv, S.; Zhang, J. Role and Effective Therapeutic Target of Gut Microbiota in Heart Failure. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2019, 2019, 5164298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wen, S.; Long-kun, D.; Man, Y.; Chang, S.; Min, Z.; Shuang-yu, L.; Xin, Q.; Jie, M.; Liang, W. Three important short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) attenuate the inflammatory response induced by 5-FU and maintain the integrity of intestinal mucosal tight junction. BMC Immunol. 2022, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, D.; Jang, C.; Neinast, M.; Edwards, J.J.; Cowan, A.; Hyman, M.C.; Rabinowitz, J.D.; Frankel, D.S.; Arany, Z. Comprehensive quantification of fuel use by the failing and nonfailing human heart. Science 2020, 370, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MYukino-Iwashita, M.; Nagatomo, Y.; Kawai, A.; Taruoka, A.; Yumita, Y.; Kagami, K.; Yasuda, R.; Toya, T.; Ikegami, Y.; Masaki, N.; et al. Short-Chain Fatty Acids in Gut–Heart Axis: Their Role in the Pathology of Heart Failure. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, V.B.M.; Arulkumaran, N.; Melis, M.J.; Gaupp, C.; Roger, T.; Shankar-Hari, M.; Singer, M. Butyrate Supplementation Exacerbates Myocardial and Immune Cell Mitochondrial Dysfunction in a Rat Model of Faecal Peritonitis. Life 2022, 12, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, J.; Jiang, H.; Jia, D.; Ou, T.; Qi, Z.; Zou, Y.; Qian, J.; Sun, A.; et al. Gut microbe-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide accelerates fibroblast-myofibroblast differentiation and induces cardiac fibrosis. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2019, 134, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organ, C.L.; Li, Z.; Sharp, T.E.; Polhemus, D.J.; Gupta, N.; Goodchild, T.T.; Tang, W.H.W.; Hazen, S.L.; Lefer, D.J. Nonlethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine N-oxide Production Improves Cardiac Function and Remodeling in a Murine Model of Heart Failure. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e016223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panagia, M.; He, H.; Baka, T.; Pimentel, D.R.; Croteau, D.; Bachschmid, M.M.; Balschi, J.A.; Colucci, W.S.; Luptak, I. Increasing mitochondrial ATP synthesis with butyrate normalizes ADP and contractile function in metabolic heart disease. NMR Biomed. 2020, 33, e4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, I.; Inoue, D.; Maeda, T.; Hara, T.; Ichimura, A.; Miyauchi, S.; Kobayashi, M.; Hirasawa, A.; Tsujimoto, G. Short-chain fatty acids and ketones directly regulate sympathetic nervous system via G protein-coupled receptor 41 (GPR41). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 8030–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinolo, M.A.R.; Rodrigues, H.G.; Hatanaka, E.; Sato, F.T.; Sampaio, S.C.; Curi, R. Suppressive effect of short-chain fatty acids on production of proinflammatory mediators by neutrophils. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2011, 22, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutengo, K.H.; Masenga, S.K.; Mweemba, A.; Mutale, W.; Kirabo, A. Gut microbiota dependant trimethylamine N-oxide and hypertension. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1075641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Qian, Z.; Yin, J.; Xu, W.; Zhou, X. The role of intestinal microbiota in cardiovascular disease. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2019, 23, 2343–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.-H.; Xin, F.-Z.; Zhou, D.; Xue, Y.-Q.; Liu, X.-L.; Yang, R.-X.; Pan, Q.; Fan, J.-G. Trimethylamine N-oxide attenuates high-fat high-cholesterol diet-induced steatohepatitis by reducing hepatic cholesterol overload in rats. World J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 25, 2450–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, M.; Mondal, P.; Ghosh, D.; Mukhopadhyay, S.K. The foul play of two dietary metabolites trimethylamine (TMA) and trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) on human health and the role of microbes in mitigating their effects. Nutrire 2023, 48, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boini, K.M.; Hussain, T.; Li, P.-L.; Koka, S.S. Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Instigates NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation and Endothelial Dysfunction. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 44, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Gregory, J.C.; Org, E.; Buffa, J.A.; Gupta, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Fu, X.; Wu, Y.; Mehrabian, M.; et al. Gut Microbial Metabolite TMAO Enhances Platelet Hyperreactivity and Thrombosis Risk. Cell 2016, 165, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montezano, A.C.; Touyz, R.M. Molecular Mechanisms of Hypertension—Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidants: A Basic Science Update for the Clinician. Can. J. Cardiol. 2012, 28, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tu, R.; Xia, J. Stroke and Vascular Cognitive Impairment: The Role of Intestinal Microbiota Metabolite TMAO. CNS Neurol. Disord.-Drug Targets 2024, 23, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, B.; Banerjee, A.; Pathak, R.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Pathak, S. Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) and cancer risk: Insights into a possible link. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2025, 192, 118592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhou, J.; Wu, W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, X. The Role of Bile Acids in Cardiovascular Diseases: From Mechanisms to Clinical Implications. Aging Dis. 2022, 14, 261–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, J.Y.L.; Ferrell, J.M. Bile Acid Metabolism in Liver Pathobiology. Gene Expr. 2018, 18, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamic, P.; Chaikijurajai, T.; Tang, W.H.W. Gut microbiome—A potential mediator of pathogenesis in heart failure and its comorbidities: State-of-the-art review. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2021, 152, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callender, C.; Attaye, I.; Nieuwdorp, M. The Interaction between the Gut Microbiome and Bile Acids in Cardiometabolic Diseases. Metabolites 2022, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grüner, N.; Mattner, J. Bile Acids and Microbiota: Multifaceted and Versatile Regulators of the Liver–Gut Axis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eblimit, Z.; Thevananther, S.; Karpen, S.J.; Taegtmeyer, H.; Moore, D.D.; Adorini, L.; Penny, D.J.; Desai, M.S. TGR5 activation induces cytoprotective changes in the heart and improves myocardial adaptability to physiologic, inotropic, and pressure-induced stress in mice. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2018, 36, e12462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, N.H.; Tang, G.; Yu, C.; Mercurio, F.; DiDonato, J.A.; Lin, A. Activation of NF-κB is required for hypertrophic growth of primary rat neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 6668–6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesel, B.; Schmid, J.A. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oeckinghaus, A.; Ghosh, S. The NF- B Family of Transcription Factors and Its Regulation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2009, 1, a000034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhai, X.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Qin, Y.; Han, J.; Meng, Y. Research progress on the relationship between bile acid metabolism and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2023, 15, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Nemet, I.; Li, X.S.; Wu, Y.; Haghikia, A.; Witkowski, M.; Koeth, R.A.; Demuth, I.; König, M.; Steinhagen-Thiessen, E.; et al. Prognostic value of gut microbe-generated metabolite phenylacetylglutamine in patients with heart failure. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2024, 26, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romano, K.A.; Nemet, I.; Prasad Saha, P.; Haghikia, A.; Li, X.S.; Mohan, M.L.; Lovano, B.; Castel, L.; Witkowski, M.; Buffa, J.A.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Generated Phenylacetylglutamine and Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2023, 16, e009972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Kong, B.; Zhu, J.; Huang, H.; Shuai, W. Phenylacetylglutamine increases the susceptibility of ventricular arrhythmias in heart failure mice by exacerbated activation of the TLR4/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2023, 116, 109795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cai, B.; Sun, Y.; Deng, H.; Wang, H.; Qiao, Z. Alteration of the gut microbiota and metabolite phenylacetylglutamine in patients with severe chronic heart failure. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 9, 1076806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, M.; Lim, J.J.; Cui, J.Y. Pregnane X Receptor and the Gut-Liver Axis: A Recent Update. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2022, 50, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, S.-M.; Oh, K.K.; Gupta, H.; Ganesan, R.; Sharma, S.P.; Jeong, J.-J.; Yoon, S.J.; Jeong, M.K.; Min, B.H.; Hyun, J.Y.; et al. The Link between Gut Microbiota and Hepatic Encephalopathy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zong, X.; Fan, Q.; Yang, Q.; Pan, R.; Zhuang, L.; Tao, R. Phenylacetylglutamine as a risk factor and prognostic indicator of heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2022, 9, 2645–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.; Zuo, K.; Fu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Xu, L.; Yang, X. Dysbiosis of Gut Microbiota and Metabolite Phenylacetylglutamine in Coronary Artery Disease Patients with Stent Stenosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 832092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Fang, C.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y.; Xu, L.; Chen, M.; Zuo, K.; Wang, L. Prognostic value of plasma phenylalanine and gut microbiota-derived metabolite phenylacetylglutamine in coronary in-stent restenosis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 944155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Li, X.; Feng, X.; Wei, M.; Luo, Y.; Zhao, T.; Xiao, B.; Xia, J. Phenylacetylglutamine, a Novel Biomarker in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 798765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Feng, X.; Li, X.; Luo, Y.; Wei, M.; Zhao, T.; Xia, J. Gut-Derived Metabolite Phenylacetylglutamine and White Matter Hyperintensities in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 675158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhao, Z.; Song, X.; Qu, H.; Liu, H. Phenylacetylglutamine is associated with the degree of coronary atherosclerotic severity assessed by coronary computed tomographic angiography in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 2021, 333, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichard, C.A.; Naelitz, B.D.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Li, J.; Stampfer, M.J.; Klein, E.A.; Hazen, S.L.; Sharifi, N. Gut Microbiome–Dependent Metabolic Pathways and Risk of Lethal Prostate Cancer: Prospective Analysis of a PLCO Cancer Screening Trial Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2022, 31, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottosson, F.; Brunkwall, L.; Smith, E.; Orho-Melander, M.; Nilsson, P.M.; Fernandez, C.; Melander, O. The gut microbiota-related metabolite phenylacetylglutamine associates with increased risk of incident coronary artery disease. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 2427–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummen, M.; Mayerhofer, C.C.K.; Vestad, B.; Broch, K.; Awoyemi, A.; Storm-Larsen, C.; Ueland, T.; Yndestad, A.; Hov, J.R.; Trøseid, M. Gut Microbiota Signature in Heart Failure Defined From Profiling of 2 Independent Cohorts. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1184–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, L.; Wirth, U.; Koch, D.; Schirren, M.; Drefs, M.; Koliogiannis, D.; Nieß, H.; Andrassy, J.; Guba, M.; Bazhin, A.V.; et al. The Role of Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides and the Intestinal Barrier in Fatty Liver Diseases. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2022, 26, 671–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, W.H.W.; Bäckhed, F.; Landmesser, U.; Hazen, S.L. Intestinal Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 2089–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacDonald, B.J.; Virani, S.A.; Zieroth, S.; Turgeon, R. Heart Failure Management in 2023: A Pharmacotherapy- and Lifestyle-Focused Comparison of Current International Guidelines. CJC Open 2023, 5, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamo, T.; Akazawa, H.; Suda, W.; Saga-Kamo, A.; Shimizu, Y.; Yagi, H.; Liu, Q.; Nomura, S.; Naito, A.T.; Takeda, N.; et al. Dysbiosis and compositional alterations with aging in the gut microbiota of patients with heart failure. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandek, A.; Bauditz, J.; Swidsinski, A.; Buhner, S.; Weber-Eibel, J.; von Haehling, S.; Schroedl, W.; Karhausen, T.; Doehner, W.; Rauchhaus, M.; et al. Altered Intestinal Function in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2007, 50, 1561–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasini, E.; Aquilani, R.; Testa, C.; Baiardi, P.; Angioletti, S.; Boschi, F.; Verri, M.; Dioguardi, F. Pathogenic Gut Flora in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. JACC Heart Fail. 2016, 4, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Du, D.; Fu, T.; Han, Y.; Li, P.; Ju, H. Alterations of the Gut Microbiota in Patients with Severe Chronic Heart Failure. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 813289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luedde, M.; Winkler, T.; Heinsen, F.; Rühlemann, M.C.; Spehlmann, M.E.; Bajrovic, A.; Lieb, W.; Franke, A.; Ott, S.J.; Frey, N. Heart failure is associated with depletion of core intestinal microbiota. ESC Heart Fail. 2017, 4, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Ye, L.; Li, J.; Jin, L.; Wang, W.; Li, S.; Bao, M.; Wu, S.; Li, L.; Geng, B.; et al. Metagenomic and metabolomic analyses unveil dysbiosis of gut microbiota in chronic heart failure patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, A.L.; O’Donnell, J.A.; Nakai, M.E.; Nanayakkara, S.; Vizi, D.; Carter, K.; Dean, E.; Ribeiro, R.V.; Yiallourou, S.; Carrington, M.J.; et al. The Gut Microbiome of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Cai, Z.; Ferrari, M.W.; Liu, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, T.; Lyu, G. The Correlation between Gut Microbiota and Serum Metabolomic in Elderly Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 5587428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsimichas, T.; Ohtani, T.; Motooka, D.; Tsukamoto, Y.; Kioka, H.; Nakamoto, K.; Konishi, S.; Chimura, M.; Sengoku, K.; Miyawaki, H.; et al. Non-ischemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with altered intestinal microbiota. Circ. J. 2018, 82, 1640–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashi, T.; Yamashita, T.; Watanabe, H.; Kami, K.; Yoshida, N.; Tabata, T.; Emoto, T.; Sasaki, N.; Mizoguchi, T.; Irino, Y.; et al. Gut microbiome and plasma microbiome-related metabolites in patients with decompensated and compensated heart failure. Circ. J. 2019, 83, 182–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidenreich, P.A.; Bozkurt, B.; Aguilar, D.; Allen, L.A.; Byun, J.J.; Colvin, M.M.; Deswal, A.; Drazner, M.H.; Dunlay, S.M.; Evers, L.R.; et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2022, 145, E895–E1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tandon, D.; Haque, M.M.; Gote, M.; Jain, M.; Bhaduri, A.; Dubey, A.K.; Mande, S.S. A prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response relationship study to investigate efficacy of fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS) on human gut microflora. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, A.C.; Moscavitch, S.D.; Faria Neto, H.C.C.; Mesquita, E.T. Probiotic therapy with Saccharomyces boulardii for heart failure patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Int. J. Cardiol. 2015, 179, 348–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, T.; Yazaki, Y.; Voors, A.A.; Jones, D.J.L.; Chan, D.C.S.; Anker, S.D.; Cleland, J.G.; Dickstein, K.; Filippatos, G.; Hillege, H.L.; et al. Association with outcomes and response to treatment of trimethylamine N-oxide in heart failure: Results from BIOSTAT-CHF. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2019, 21, 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espinoza, C.; Alkhateeb, H.; Siddiqui, T. Updates in pharmacotherapy of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.-L.; Chen, M.; Fu, X.-D.; Yang, M.; Hrmova, M.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Mou, H.-J. Potassium Alginate Oligosaccharides Alter Gut Microbiota, and Have Potential to Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moludi, J.; Saiedi, S.; Ebrahimi, B.; Alizadeh, M.; Khajebishak, Y.; Ghadimi, S.S. Probiotics Supplementation on Cardiac Remodeling Following Myocardial Infarction: A Single-Center Double-Blind Clinical Study. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res. 2021, 14, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, M.; Kitada, Y.; Shimomura, Y.; Naito, Y. Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis LKM512 reduces levels of intestinal trimethylamine produced by intestinal microbiota in healthy volunteers: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 36, 94–101, Corrigendum in J. Funct. Foods 2018, 42, 387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jff.2017.08.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Bergeron, N.; Levison, B.S.; Li, X.S.; Chiu, S.; Jia, X.; Koeth, R.A.; Li, L.; Wu, Y.; Tang, W.H.W.; et al. Impact of chronic dietary red meat, white meat, or non-meat protein on trimethylamine N-oxide metabolism and renal excretion in healthy men and women. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.Z.; Nelson, E.; Chu, P.-Y.; Horlock, D.; Fiedler, A.; Ziemann, M.; Tan, J.K.; Kuruppu, S.; Rajapakse, N.W.; El-Osta, A.; et al. High-Fiber Diet and Acetate Supplementation Change the Gut Microbiota and Prevent the Development of Hypertension and Heart Failure in Hypertensive Mice. Circulation 2017, 135, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Wang, X.; Feng, W.; Liu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Q.; Cai, L. The gut microbiota and its interactions with cardiovascular disease. Microb. Biotechnol. 2020, 13, 637–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khannous-Lleiffe, O.; Willis, J.R.; Saus, E.; Cabrera-Aguilera, I.; Almendros, I.; Farré, R.; Gozal, D.; Farré, N.; Gabaldón, T. A Mouse Model Suggests That Heart Failure and Its Common Comorbidity Sleep Fragmentation Have No Synergistic Impacts on the Gut Microbiome. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fudim, M.; Sobotka, P.A.; Piccini, J.P.; Patel, M.R. Renal Denervation for Patients with Heart Failure. Circ. Heart Fail. 2021, 14, E008301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böhm, M.; Kario, K.; Kandzari, D.E.; Mahfoud, F.; Weber, M.A.; Schmieder, R.E.; Tsioufis, K.; Pocock, S.; Konstantinidis, D.; Choi, J.W.; et al. Efficacy of catheter-based renal denervation in the absence of antihypertensive medications (SPYRAL HTN-OFF MED Pivotal): A multicentre, randomised, sham-controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 395, 1444–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, S.; Liu, C.; Li, S.; Chen, P. Renal Denervation Mitigated Fecal Microbiota Aberrations in Rats with Chronic Heart Failure. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2021, 2021, 1697004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamic, P.; Snyder, M.; Tang, W.H.W. Gut Microbiome-Based Management of Patients with Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 81, 1729–1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Jin, W.; Liu, S.; Jiao, Z.; Li, X. Probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics in health and disease. MedComm 2023, 4, e420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, S.; Mande, S.S. Host-microbiome interactions: Gut-Liver axis and its connection with other organs. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2022, 8, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, W.E.; Greiling, T.M.; Kriegel, M.A. Host–microbiota interactions in immune-mediated diseases. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 521–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Method | Principle | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culturomics | Traditional approach where live microorganisms are cultivated on selective media under controlled conditions. | - Cost-effective - Widely accessible - Allows detailed phenotypic analysis (e.g., pathogenicity, antibiotic resistance, metabolic functions) - Suitable for aerotolerant organisms and rare bacteria poorly represented in databases. | - Labor-intensive - Limited to cultivable microbes - Results influenced by media and conditions - Challenges in studying strict anaerobes or capturing microbe interactions in mixed communities. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) | Sequencing-based method targeting specific microbial genes for detection and quantification (e.g., qPCR, RT-PCR). | - Rapid and widely available - Cost-effective - Provides absolute abundance of target taxa - High dynamic range. | - Targets limited number of genes/microbes - Unable to detect unknown taxa - Susceptible to PCR biases - Results depend on primer and probe specificity. |

| 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing | Amplification and sequencing of hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene, followed by matching reads to reference databases. | - Commonly used for taxonomic profiling - Identifies cultured and uncultured microbes at the genus level - Relatively rapid and cost-efficient - Well-developed bioinformatic pipelines. | - Provides relative abundance only - Low resolution at species/strain level - Limited to bacteria and archaea; fungi require specialized primers - Cannot distinguish live versus dead microbes - Lacks functional insights. |

| Shotgun Metagenomics | High-throughput sequencing of all DNA fragments in a sample, followed by computational assembly and taxonomic/functional annotation. | - Identifies bacteria, archaea, viruses, and fungi - Provides species and strain-level resolution - Offers functional potential characterization - Requires minimal DNA input (<1 ng). | - Computationally intensive - Costly (though decreasing) - Requires advanced bioinformatics - Sequencing host DNA may confound results - Reproducibility remains uncertain. |

| Meta-transcriptomics | Sequencing of RNA transcripts to analyze microbiome gene expression. | - Enables real-time profiling of microbial activity - Quantitative and high resolution - Integrates functional insights with metagenomics for comprehensive analysis. | - Technically complex and costly - RNA instability poses challenges - Requires paired metagenomic data for optimal interpretation - Limited correlation with meta-proteomic outputs. |

| Meta-proteomics | Mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantification of microbiome-derived proteins and peptides. | - Provides functional insights into microbial protein expression. - Can reveal host-microbe protein interactions. | - Technically challenging - Requires high-quality reference libraries - Limited sensitivity for low-abundance proteins. |

| Metabolomics | Identification and quantification of microbial metabolites using chromatography and MS. | - Rapid and versatile - Suitable for various sample types (e.g., feces, urine, plasma) - Facilitates discovery of both known and novel metabolites - Low sample requirement. | - Targeted metabolomics identifies known compounds but misses unknowns - Untargeted methods are less quantitative and challenging for metabolite annotation - Limited ability to link metabolites to specific microbial taxa. |

| Multiomics | Integration of multiple data types (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) from the same or concurrent samples. | - Offers a comprehensive systems-level view of microbiome-host interactions - Generates novel hypotheses. | - Costly and computationally demanding - Analytic methods and pipelines are still being standardized. |

| Reference | Patient Type | Age (Years) | Sample Size | Method | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [89] | Acute HF or exacerbation of chronic HF | 47.4 ± 2.8 (younger HF) 73.8 ± 2.8 (older HF) | HF < 60: n = 12 HF > 60: n = 10 Controls: n = 12 | 16S rRNA | ↓ Eubacterium rectale, Dorea longicatena Depletion of Faecalibacterium in older patients |

| [90] | Chronic HF | 67 ± 2 | Chronic HF: n = 22 Controls: n = 22 | Fluorescence in situ hybridization | ↑ Eubacterium rectale, Faecalibacterium |

| [91] | Chronic HF | 65 ± 1.2 | HF: n= 60 Controls: n = 20 | Traditional culture techniques | ↑ Campylobacter, Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia enterolytica, Candida |

| [92] | Chronic HF | 60.69 | HF: n = 29 Controls: n = 30 | 16S rRNA | ↓ Ruminococcaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Dialister ↑ Enterococcus, Enterococcaceae |

| [92] | Chronic HF (NYHA III-IV) | 65–86 | NYHA III HF: n = 29 NYHA IV HF: n = 29 Controls: n = 22 | 16S rRNA | NYHA III: ↑ Escherichia, Bifidobacterium NYHA IV: ↑ Klebsiella, Lactobacillus |

| [93] | Chronic HF (70% exacerbation, 30% stable) | 65 ± 3.2 | HF: n = 20 Controls: n = 20 | 16S rRNA | ↓ Coriobacteriaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae, Ruminococcaceae (family level) ↓ Blautia (genus level) |

| [85] | Chronic HF | NA | Discovery: n = 40 Validation: n = 44 Controls: n = 266 | 16S rRNA | ↓ Lachnospiraceae family |

| [94] | Stable chronic HF (ischemic/dilated cardiomyopathy) | 58.1 ± 13.3 | HF: n = 53 Controls: n = 41 | 16S rRNA | ↑ Ruminococcus gnavus ↓ Faecalibacterium prausnitzii |

| [95] | HF with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) | 40–70 | HFpEF: n = 26 Controls: n = 67 | 16S rRNA | ↓ Ruminococcus spp. |

| [96] | Chronic HF | 65 ± 3.17 | HF: n = 26 Controls: n = 26 | 16S rRNA | ↑ Escherichia, Shigella, Ruminococcaceae, Lactobacillus, Atopobium, Romboutsia, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Klebsiella |

| [97] | Non-ischemic HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) | 18–70 | HFrEF: n = 28 Controls: n = 19 | 16S rRNA | ↑ Streptococcus spp., Veillonella spp. ↓ SMB53 |

| [98] | Acute decompensated HF/acute worsening of chronic HF | 72 ± 18 | HF: n = 22 Controls: n = 11 | 16S rRNA | ↑ Actinomycetota (phylum), Bifidobacterium (genus) ↓ Megamonas (genus) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Orjichukwu, C.K.; Orjichukwu, R.O.; Akpunonu, P.K.; Ugwu, P.C.; Nnabuife, S.G. Microbiome and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Gut Health and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Heart Failure Progression. Med. Sci. 2025, 13, 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040302

Orjichukwu CK, Orjichukwu RO, Akpunonu PK, Ugwu PC, Nnabuife SG. Microbiome and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Gut Health and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Heart Failure Progression. Medical Sciences. 2025; 13(4):302. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040302

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrjichukwu, Chukwudi Kingsley, Rita Ogochukwu Orjichukwu, Peter Kanayochukwu Akpunonu, Paul Chikwado Ugwu, and Somtochukwu Godfrey Nnabuife. 2025. "Microbiome and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Gut Health and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Heart Failure Progression" Medical Sciences 13, no. 4: 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040302

APA StyleOrjichukwu, C. K., Orjichukwu, R. O., Akpunonu, P. K., Ugwu, P. C., & Nnabuife, S. G. (2025). Microbiome and Heart Failure: A Comprehensive Review of Gut Health and Microbiota-Derived Metabolites in Heart Failure Progression. Medical Sciences, 13(4), 302. https://doi.org/10.3390/medsci13040302