Spatial and Temporal Variability of Throughfall among Oak and Co-Occurring Non-Oak Tree Species in an Upland Hardwood Forest

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Site Description

2.2. Field Methods

3. Results

3.1. General Throughfall Trends

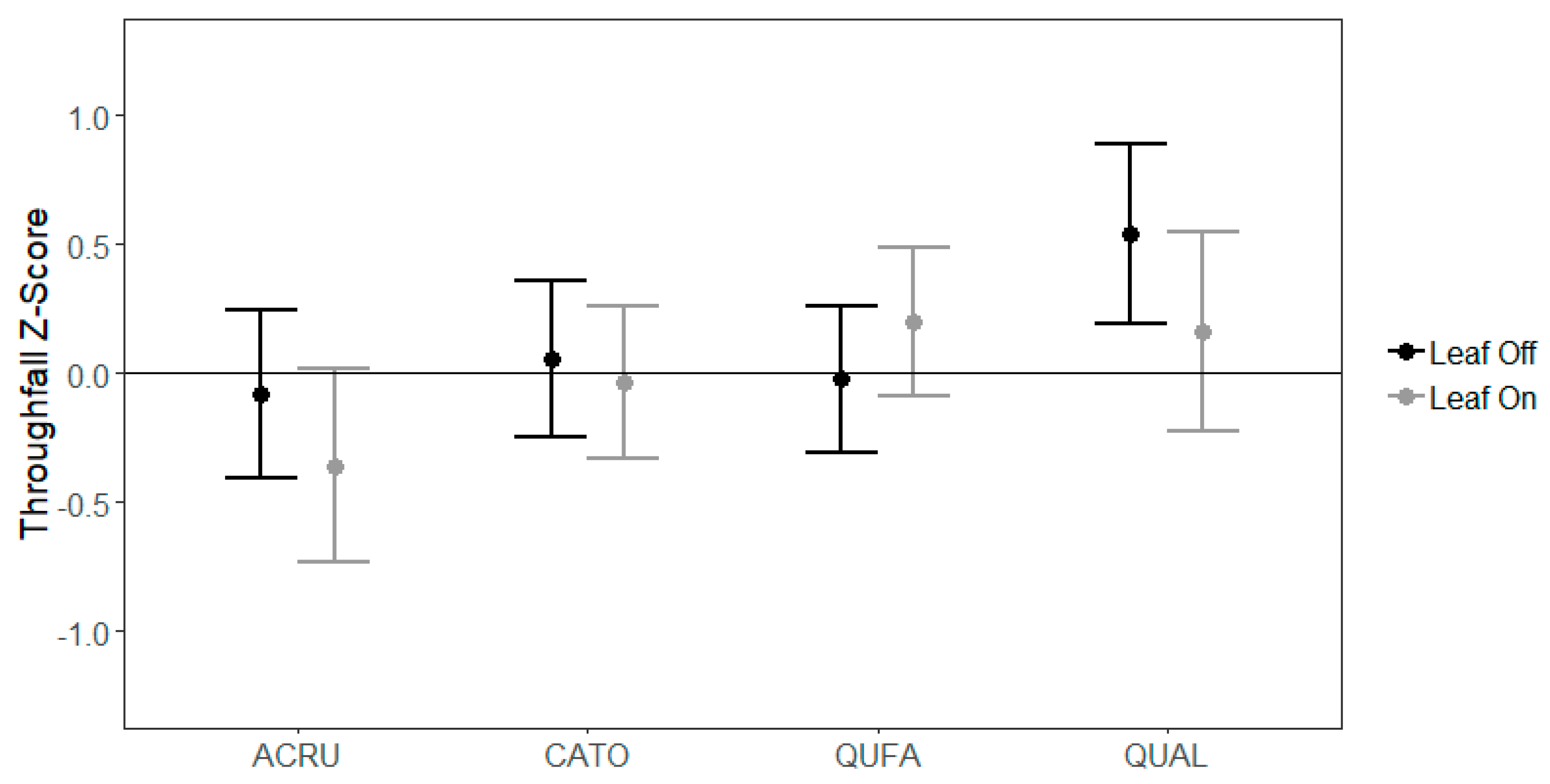

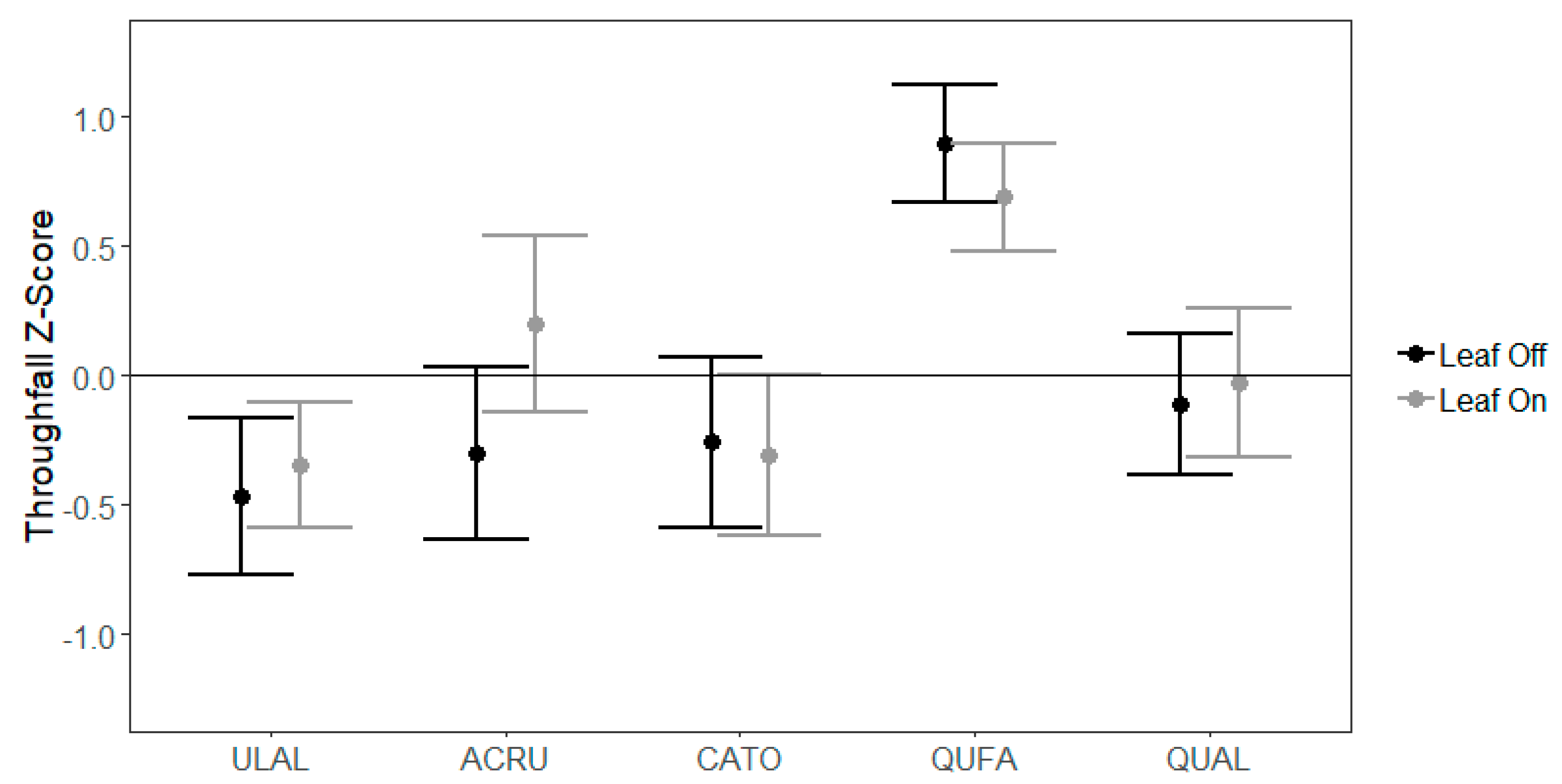

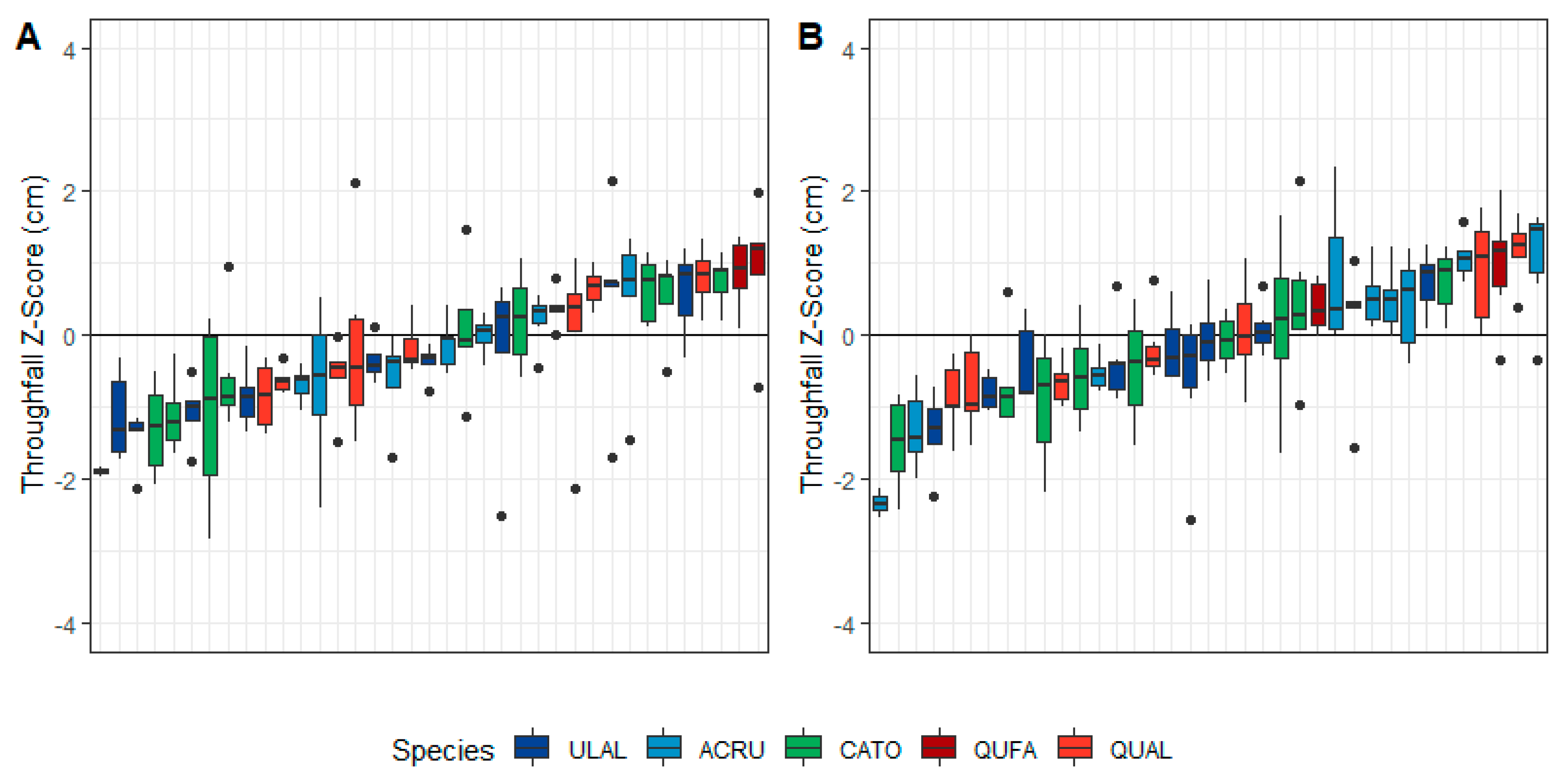

3.2. Species-Level Variability

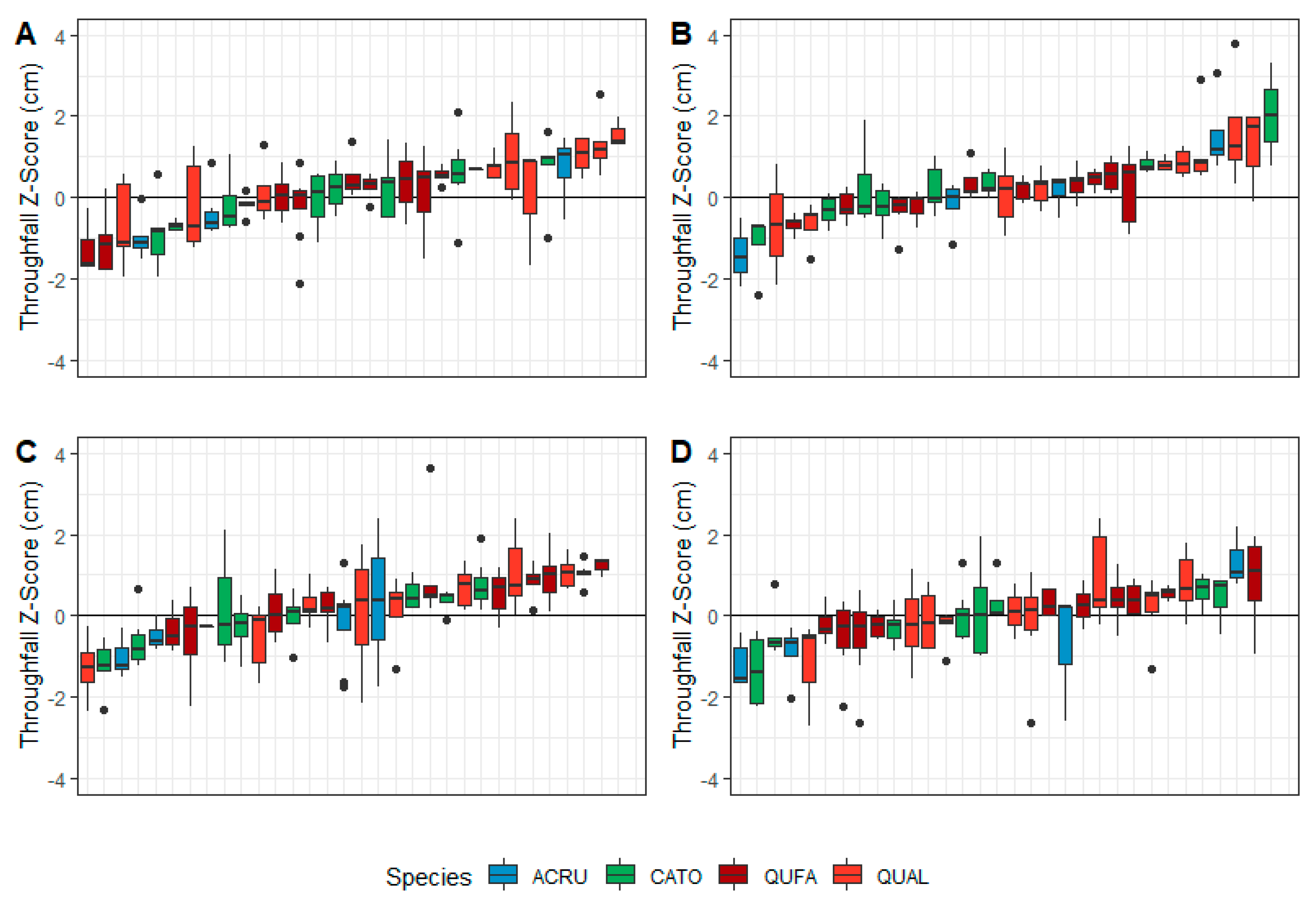

3.3. Gauge-Level Variability

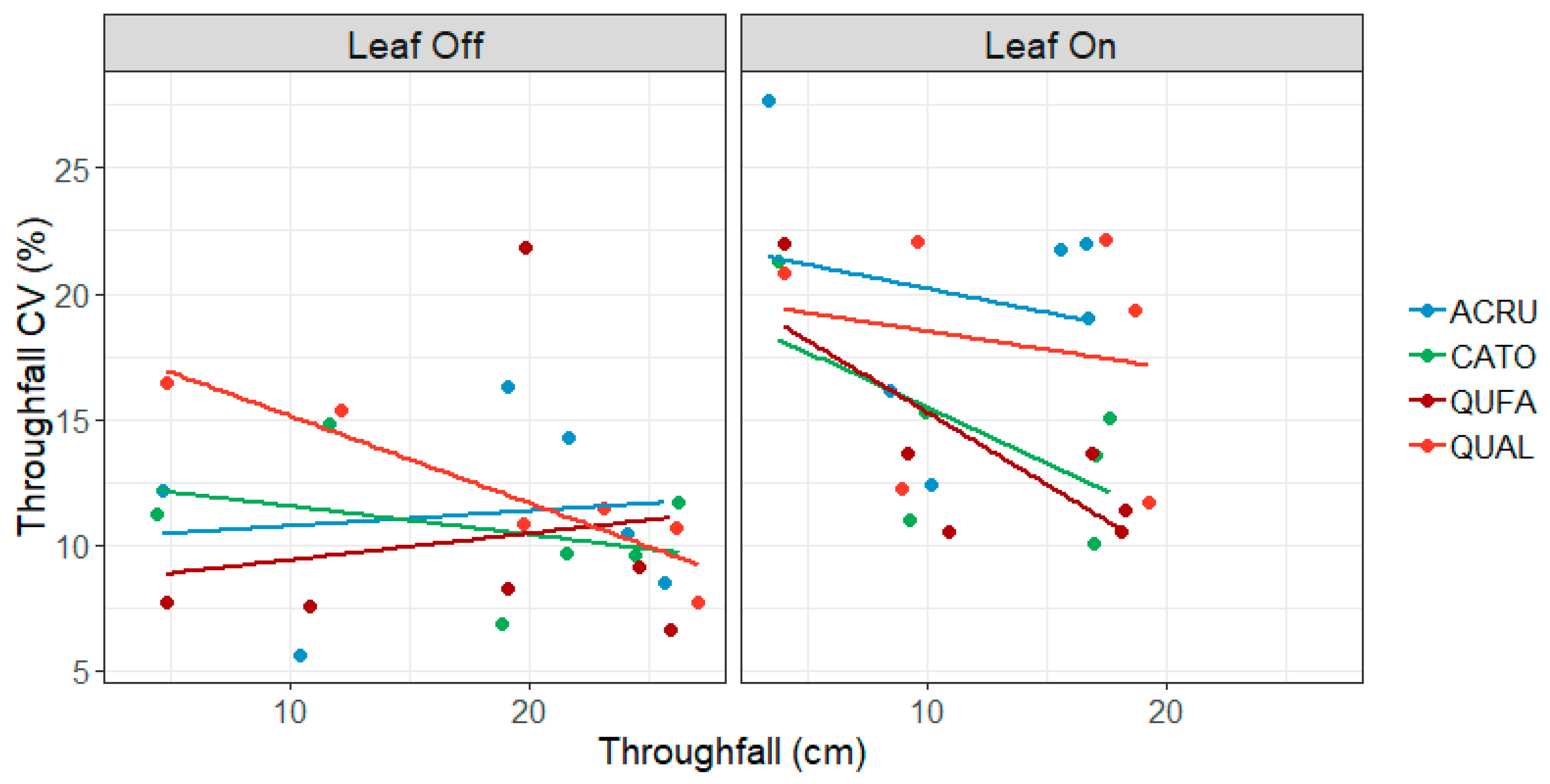

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Knott, J.A.; Desprez, J.M.; Oswalt, C.M.; Fei, S. Shifts in forest composition in the eastern United States. For. Ecol. Manag. 2019, 433, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, M.D. Where has all the white oak gone? Bioscience 2003, 53, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, S.; Steiner, K.C. Evidence for increasing red maple abundance in the eastern United States. For. Sci. 2007, 53, 473–477. [Google Scholar]

- Nowacki, G.J.; Abrams, M.D. The demise of fire and “mesophication” of forests in the eastern United States. Bioscience 2008, 58, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, P.V.; Miniat, C.F.; Elliott, K.J.; Swank, W.T.; Brantley, S.T.; Laseter, S.H. Declining water yield from forested mountain watersheds in response to climate change and forest mesophication. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2016, 22, 2997–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, J.H.; Barker, A.C. An analysis of throughfall and stemflow in mixed oak stands. Water Resour. Res. 1970, 6, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, J. The influence of physical and physiological characteristics of vegetation on their hydrological response. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 2885–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levia, D.F.; Germer, S. A review of stemflow generation dynamics and stemflow-environment interactions in forests and shrublands. Rev. Geophys. 2015, 53, 673–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanko, K.; Hudson, S.A.; Levia, D.F. Differences in throughfall drop size distributions in the presence and absence of foliage. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 620–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.D. Leaf water repellency of species in Guatemala and Colorado (USA) and its significance to forest hydrology studies. J. Hydrol. 2007, 336, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papierowska, E.; Szporak-Wasilewska, S.; Szewińska, J.; Szatyłowicz, J.; Debaene, G.; Utratna, M. Contact angle measurements and water drop behavior on leaf surface for several deciduous shrub and tree species from a temperate zone. Trees 2018, 32, 1253–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crockford, R.H.; Richardson, D.P. Partitioning of rainfall into throughfall, stemflow and interception: Effect of forest type, ground cover and climate. Hydrol. Process. 2000, 14, 2903–2920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Cameron, J.L. The influence of canopy traits on throughfall and stemflow in five tropical trees growing in a Panamanian plantation. For. Ecol. Manag. 2008, 255, 1915–1925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Zimmermann, B. Requirements for throughfall monitoring: The roles of temporal scale and canopy complexity. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 189, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, A.; Wilcke, W.; Elsenbeer, H. Spatial and temporal patterns of throughfall quantity and quality in a tropical montane forest in Ecuador. J. Hydrol. 2007, 343, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holwerda, F.; Scatena, F.N.; Bruijnzeel, L.A. Throughfall in a Puerto Rican lower montane rain forest: A comparison of sampling strategies. J. Hydrol. 2006, 327, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staelens, J.; De Schrijver, A.; Verheyen, K.; Verhoest, N.E.C. Spatial variability and temporal stability of throughfall water under a dominant beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) tree in relationship to canopy cover. J. Hydrol. 2006, 330, 651–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nanko, K.; Onda, Y.; Ito, A.; Moriwaki, H. Spatial variability of throughfall under a single tree: Experimental study of rainfall amount, raindrops, and kinetic energy. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2011, 151, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, C.M.; Levia, D.F.; Hudson, S.A.; Dowtin, A.L.; Zhang, F.; Mitchell, M.J. Small-scale topographic variability influences tree species distribution and canopy throughfall partitioning in a temperate deciduous forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 359, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, H.D.; Arthur, M.A. Implications of a predicted shift from upland oaks to red maple on forest hydrology and nutrient availability. Can. J. For. Res. 2010, 726, 716–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, C.M.; Limpert, K.E.; Drotar, N.; Siegle-Gaither, M.; Burton, M.; Lowery, J.; Alexander, H.D. Effects of canopy structure on water cycling: Implications for changing forest composition. In Proceedings of the 20th Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research Conference, Shreveport, LA, USA, 12–14 March 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Van Stan, J.T.; Lewis, E.S.; Hildebrandt, A.; Rebmann, C.; Friesen, J. Impact of interacting bark structure and rainfall conditions on stemflow variability in a temperate beech-oak forest, central Germany. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2016, 61, 2071–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, G.G.; Cardon, M.E.; Kiernan, D.H. Variation in Acer saccharum Marshall (Sugar Maple) Bark and Stemflow Characteristics: Implications for Epiphytic Bryophyte Communities. Northeast. Nat. 2019, 26, 214–235. [Google Scholar]

- Arguez, A.; Durre, I.; Applequist, S.; Squires, M.; Vose, R.; Yin, X.; Bilotta, R. NOAA’s U.S. Climate Normals (1981–2020). NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, doi:10.7289/V5PN93JP. Available online: https://data.nodc.noaa.gov/cgi-bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ncdc:C00824# (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Soil Survey Staff, Natural Resources Conservation Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Web Soil Survey. Available online: https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/ (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Granger, J.J.; Buckley, D.S.; Sharik, T.L.; Zobel, J.M.; DeBord, W.W.; Hartman, J.P.; Henning, J.G.; Keyser, T.L.; Marshall, J.M. Northern red oak regeneration: 25-year results of cutting and prescribed fire in Michigan oak and pine stands. For. Ecol. Manag. 2018, 429, 467–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyser, T.L.; Arthur, M.; Loftis, D.L. Repeated burning alters the structure and composition of hardwood regeneration in oak-dominated forests of eastern Kentucky, USA. For. Ecol. Manag. 2017, 393, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, D.; Dick, C.W.; Strayer, E.; Perfecto, I.; Vandermeer, J. Scale and strength of oak-mesophyte interactions in a transitional oak-hickory forest. Can. J. For. Res. 2018, 48, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, H.D.; Arthur, M.A. Increasing red maple leaf litter alters decomposition rates and nitrogen cycling in historically oak-dominated forests of the eastern U.S. Ecosystems 2014, 17, 1371–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.; Maechler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Package Lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using Eigen and S4. R Package version 1.1-21. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/lme4/index.html (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Lenth, R.; Singmann, H.; Love, J.; Buerkner, P.; Herve, M. Package emmeans: Estimated Marginal Means, aka Least-Squares Means. R package version 1.4.1. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/emmeans/index.htm.l (accessed on 30 July 2019).

- Yang, X.D.; Yan, E.R.; Chang, S.X.; Da, L.J.; Wang, X.H. Tree architecture varies with forest succession in evergreen broad-leaved forests in Eastern China. Trees 2015, 29, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobe, R.K.; Pacala, S.W.; Silander, J.A.; Canham, C.D. Juvenile tree survivorship as a component of shade tolerance. Ecol. Appl. 1995, 5, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinemets, Ü. Growth of young trees of Acer platanoides and Quercus robur along a gap-understory continuum: interrelationships between allometry, biomass partitioning, nitrogen, and shade tolerance. Int. J. Plant Sci. 1998, 159, 318–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiba, S.I.; Kohyama, T. Crown architecture and life-history traits of 14 tree species in a warm-temperate rain forest: Significance of spatial heterogeneity. J. Ecol. 1997, 85, 611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staelens, J.; De Schrijver, A.; Verheyen, K.; Verhoest, N.E.C. Spatial variability and temporal stability of throughfall deposition under beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in relationship to canopy structure. Environ. Pollut. 2006, 142, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritter, A.; Regalado, C.M. Investigating the random relocation of gauges below the canopy by means of numerical experiments. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2010, 150, 1102–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, R.F.; Skaugset, A.E.; Weiler, M. Temporal persistence of spatial patterns in throughfall. J. Hydrol. 2005, 314, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holder, C.D.; Gibbes, C. Influence of leaf and canopy characteristics on rainfall interception and urban hydrology. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2017, 62, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusk, C.H. Leaf area and growth of juvenile temperate evergreens in low light: Species of contrasting shade tolerance change rank during ontogeny. Funct. Ecol. 2004, 18, 820–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegert, C.M.; Levia, D.F.; Leathers, D.J.; Van Stan, J.T.; Mitchell, M.J. Do storm synoptic patterns affect biogeochemical fluxes from temperate deciduous forest canopies? Biogeochemistry 2017, 132, 273–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keim, R.F.; Link, T.E. Linked spatial variability of throughfall amount and intensity during rainfall in a coniferous forest. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 248, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staelens, J.; De Schrijver, A.; Verheyen, K.; Verhoest, N.E.C. Rainfall partitioning into throughfall, stemflow, and interception within a single beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) canopy: Influence of foliation, rain event characteristics, and meteorology. Hydrol. Process. 2008, 22, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, B.A.; Matt, D.R. The distribution of solar radiation within a deciduous forest. Ecol. Monogr. 1977, 47, 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, I.J.; Reich, P.B.; Westoby, M.; Ackerly, D.D.; Baruch, Z.; Bongers, F.; Cavender-Bares, J.; Chapin, T.; Cornelissen, J.H.C.; Diemer, M.; et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature 2004, 428, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augspurger, C.K.; Bartlett, E.A. Differences in leaf phenology between juvenile and adult trees in a temperate deciduous forest. Tree Physiol. 2003, 23, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klamerus-Iwan, A.; Witek, W. Variability in the wettability and water storage capacity of common oak leaves (Quercus robur L.). Water 2018, 10, 695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, T.W.; Untersteiner, H.; Toplitzer, M.; Neubauer, C. Nutrient fluxes in pure and mixed stands of spruce (Picea abies) and beech (Fagus sylvatica). Plant Soil 2009, 322, 317–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staelens, J.; De Schrijver, A.; Verheyen, K. Seasonal variation in throughfall and stemflow chemistry beneath a European beech (Fagus sylvatica) tree in relation to canopy phenology. Can. J. For. Res. 2007, 37, 1359–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legout, A.; van der Heijden, G.; Jaffrain, J.; Boudot, J.P.; Ranger, J. Tree species effects on solution chemistry and major element fluxes: A case study in the Morvan (Breuil, France). For. Ecol. Manag. 2016, 378, 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisci, S.; Rogora, M.; Marchetto, A.; Dichiaro, F. The role of forest type in the variability of DOC in atmospheric deposition at forest plots in Italy. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 3415–3425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiklomanov, A.N.; Levia, D.F. Stemflow acid neutralization capacity in a broadleaved deciduous forest: The role of edge effects. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 193C, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.C.; Rodriguez, H.G. Interception loss, throughfall and stemflow chemistry in pine and oak forests in northeastern Mexico. Tree Physiol. 2001, 21, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, L.D.; Van Stan, J.T.; Gay, T.E.; Rosier, C.; Wu, T. Alteration of soil chitinolytic bacterial and ammonia oxidizing archaeal community diversity by rainwater redistribution in an epiphyte-laden Quercus virginiana canopy. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2016, 100, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosier, C.L.; Levia, D.F.; Van Stan, J.T.; Aufdenkampe, A.; Kan, J. Seasonal dynamics of the soil microbial community structure within the proximal area of tree boles: Possible influence of stemflow. Eur. J. Soil Biol. 2016, 73, 108–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachey, M.E.; Pound, P.; Ottesen, E.A.; Van Stan, J.T. Bacterial Community Composition of Throughfall and Stemflow. Front. For. Glob. Chang. 2018, 1, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribbons, R.R.; Kepfer-Rojas, S.; Kosawang, C.; Hansen, O.K.; Ambus, P.; McDonald, M.; Grayston, S.J.; Prescott, C.E.; Vesterdal, L. Context-dependent tree species effects on soil nitrogen transformations and related microbial functional genes. Biogeochemistry 2018, 140, 145–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | N | Density (ha−1) | DBH (cm) | BA (cm2) | CA (m2) | CA:BA (m2 m−2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overstory | ||||||

| Mockernut hickory (CATO) | 9 | 20 | 31.9 ± 4.0 | 900 ± 223 | 22.2 ± 13.1 | 247 |

| Red maple (ACRU) | 4 | 2 | 17.4 ± 0.6 | 238 ± 15 | 43.5 ± 9.3 | 1829 |

| Southern red oak (QUFA) | 9 | 38 | 35.1 ± 3.1 | 1037 ± 177 | 7.7 ± 1.2 | 74 |

| White oak (QUAL) | 9 | 36 | 28.5 ± 5.8 | 852 ± 290 | 60.1 ± 28.6 | 706 |

| Midstory | ||||||

| Mockernut hickory (CATO) | 9 | 225 | 6.4 ± 1.8 | 53 ± 36 | 24.2 ± 4.2 | 4588 |

| Red maple (ACRU) | 9 | 163 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | 12 ± 5 | 29.0 ± 6.5 | 23,837 |

| Winged elm (ULAL) | 2 | 657 | 6.7 ± 0.4 | 35 ± 5 | 32.7 ± 2.2 | 9380 |

| Southern red oak (QUFA) | 9 | 12 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 20 ± 7 | 39.4 ± 9.2 | 19,434 |

| White oak (QUAL) | 8 | 36 | 6.4 ± 2.5 | 67 ± 52 | 14.1 ± 2.9 | 2113 |

| Deployment Date 1 | Collection Date 1 | Leaf Phase | Rainfall (cm) | Midstory TF (cm) (%) | Overstory TF (cm) (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 November 2017 | 9 December 2017 | Off | 4.9 | 4.3 | 87.8 | 4.7 | 95.9 |

| 9 December 2017 | 21 January 2018 | Off | 23.3 | 18.8 | 80.7 | 19.2 | 82.4 |

| 21 January 2018 | 15 February 2018 | Off | 23.1 | 21.2 | 91.8 | 21.4 | 92.6 |

| 15 February 2018 | 8 March 2018 | Off | 29.6 | 23.8 | 80.4 | 24.8 | 83.8 |

| 8 March 2018 | 7 April 2018 | On | 19.2 | 16.8 | 87.5 | 17.2 | 90.0 |

| 7 April 2018 | 2 May 2018 | On | 8.8 | 8.5 | 96.6 | 9.1 | 103.4 |

| 2 May 2018 | 6 June 2018 | On | 11.1 | 10.0 | 90.1 | 10.2 | 91.9 |

| 3 August 2018 | 2 September 2018 | On | 4.7 | 4.0 | 85.1 | 3.7 | 78.7 |

| 2 September 2018 | 11 October 2018 | On | 14.9 | 17.7 | 118.7 | 17.8 | 119.5 |

| 11 October 2018 | 16 November 2018 | On | 22.6 | 17.8 | 78.8 | 18.0 | 79.6 |

| 16 November 18 | 13 December 18 | Off | 12.4 | 10.7 | 86.3 | 11.3 | 91.1 |

| 13 December 2018 | 2 February 2019 | Off | 28.7 | 25.1 | 87.5 | 26.2 | 91.3 |

| Total | 203.3 | 179.3 | 88.2 | 183.6 | 90.3 | ||

| Overstory | Midstory | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Χ2 | D.F. | p-Value | Χ2 | D.F. | p-Value | |

| Species | 9.433 | 3 | 0.024 | 5.578 | 4 | 0.233 |

| Leaf Phase | 0.180 | 1 | 0.672 | 3.125 | 1 | 0.077 |

| Gauge Location | 2.642 | 1 | 0.104 | |||

| Species:Leaf Phase | 12.518 | 3 | 0.006 | 9.384 | 4 | 0.052 |

| Species:Gauge Location | 0.915 | 3 | 0.822 | |||

| Leaf Phase:Gauge Location | 2.191 | 1 | 0.139 | |||

| Species:Leaf Phase:Gauge Location | 2.615 | 3 | 0.455 | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Siegert, C.M.; Drotar, N.A.; Alexander, H.D. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Throughfall among Oak and Co-Occurring Non-Oak Tree Species in an Upland Hardwood Forest. Geosciences 2019, 9, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9100405

Siegert CM, Drotar NA, Alexander HD. Spatial and Temporal Variability of Throughfall among Oak and Co-Occurring Non-Oak Tree Species in an Upland Hardwood Forest. Geosciences. 2019; 9(10):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9100405

Chicago/Turabian StyleSiegert, Courtney M., Natasha A. Drotar, and Heather D. Alexander. 2019. "Spatial and Temporal Variability of Throughfall among Oak and Co-Occurring Non-Oak Tree Species in an Upland Hardwood Forest" Geosciences 9, no. 10: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9100405

APA StyleSiegert, C. M., Drotar, N. A., & Alexander, H. D. (2019). Spatial and Temporal Variability of Throughfall among Oak and Co-Occurring Non-Oak Tree Species in an Upland Hardwood Forest. Geosciences, 9(10), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences9100405