Abstract

Accurate evaluation of unsaturated shear strength remains a significant challenge in geotechnical engineering because of the nonlinear interaction between matric suction and shear strength. Existing models often assume a linear contribution of suction and are generally restricted to low suction ranges, limiting their predictive capability under highly unsaturated conditions. This study investigated the nonlinear response of unsaturated shear strength through single-stage direct shear tests conducted under constant water content. Two soil types: a high-plasticity clay and a low-plasticity silty clay were examined across a wide suction range extending beyond the air-entry value (AEV). The results revealed a nonlinear behavior expressed as a distinct bi-linear trend, with shear strength increasing with suction up to the optimal moisture condition and then exhibiting a clearly altered rate of increase at higher suction levels. To capture this nonlinear behavior of unsaturated shear strength with suction, an exponential shear strength equation was proposed and validated using eight additional published datasets encompassing different soil classifications and suction magnitudes. The proposed formulation demonstrates that accounting for non-linearity is essential for accurately estimating the unsaturated shear strength of the soil. Moreover, the proposed exponential model outperforms both the well-established linear model of Fredlund and the nonlinear power law model of Abramento and Carvalho, thereby providing a unified framework for capturing the nonlinear interaction of matric suction on unsaturated shear strength.

1. Introduction

Most natural soils in arid and semi-arid regions exist in a partially saturated state [1,2,3], where both air and water coexist within the pore spaces, significantly influencing their mechanical and hydraulic behavior. The presence of negative pore-water pressure, or matric suction, within the unsaturated zone contributes to an apparent cohesion that enhances the overall shear strength of the soil. Consequently, the magnitude of suction and its variation with moisture content play a pivotal role in defining the stability and deformation characteristics of geotechnical systems involving slopes, embankments, and pavements in these regions. Understanding and quantifying this relationship is therefore essential for reliable geotechnical analysis and design under fluctuating moisture conditions [2,3].

The mechanical behavior of unsaturated soils is commonly described in terms of two independent stress state variables: the net normal stress () and the matric suction () [2]. Traditional shear strength formulations, originally developed for saturated conditions, were later extended to incorporate the additional effects introduced by partial saturation. Early classical criteria such as the Mohr–Coulomb [4], Tresca [5], and von Mises [6] frameworks provided a foundation for describing shear failure but did not consider the influence of multiple pore fluid phases. With the establishment of appropriate stress state variables, these classical models were generalized to capture the behavior of unsaturated soils. Fredlund et al. [7] advanced this concept by extending the Mohr–Coulomb criterion to include both the net normal stress and matric suction as independent components of the stress state. The resulting relationship, widely known as the extended Mohr–Coulomb failure envelope, defines the shear strength of an unsaturated soil as:

where is the shear stress on the failure plane at failure, is the effective apparent cohesion, is the net normal stress on the failure plane at failure, is the angle of internal friction, is the matric suction on the failure plane at failure, and is the angle indicating the rate of increase in shear strength with respect to a change in matric suction.

Over the past several decades, numerous researchers have proposed a variety of theoretical frameworks and empirical formulations to predict or estimate the shear strength of unsaturated soils [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. These models differ primarily in how they account for suction, stress state variables, and soil–water interaction mechanisms. A concise summary of representative shear strength models developed from these approaches is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of representative predictive models for estimating the shear strength of unsaturated soils.

Extensive efforts have been made to formulate empirical and semi-empirical expressions for predicting the shear strength of unsaturated soils; however, most existing models remain inadequate in representing the nonlinear behavior manifested at high suction levels [2,3,14]. Experimental and theoretical investigations consistently demonstrate that once the matric suction exceeds the air-entry value (AEV), the shear strength response deviates from linearity, attributed to progressive changes in capillary stress distribution, suction-induced apparent cohesion, and microstructural evolution within the soil matrix [2,15,23,24,25]. Nonetheless, the development of constitutive relationships capable of accurately reproducing this behavior over an extended suction range remains limited [26,27,28,29]. To advance current understanding, this study presents a generalized nonlinear unsaturated shear strength formulation that captures the normal stress and suction–strength interactions across a wide suction spectrum. The proposed model is calibrated using controlled experimental data and validated against published datasets encompassing a range of soil types and mineralogical compositions, thereby addressing a critical gap in existing predictive frameworks for unsaturated soil shear strength.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

In this study, two soils were investigated: a frost-susceptible soil provided from the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and an expansive soil obtained from the Texas Department of Transportation (TxDOT). To complement these laboratory-tested materials, datasets from published literature were incorporated to validate the proposed model across a broader range of soil types and to demonstrate their wider applicability.

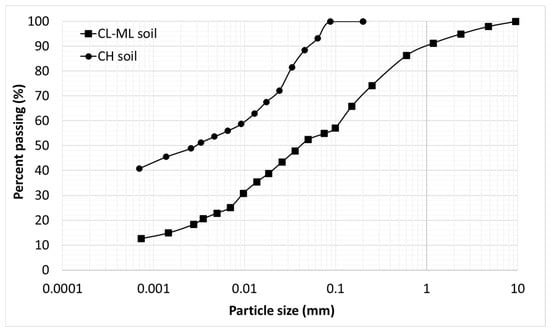

The material characterization results are presented to establish the basis for subsequent analyses. The index properties of the laboratory-tested soils are summarized in Table 2, and those compiled from published datasets are provided in Table 3. The particle size distribution curves for the laboratory-tested soils are illustrated in Figure 1. According to the Unified Soil Classification System (USCS), the frost-susceptible soil was classified as a low-plasticity silty clay (CL–ML), whereas the expansive soil was identified as a high-plasticity clay (CH).

Table 2.

Summary of basic soil properties.

Table 3.

Summary of soil properties obtained from literature.

Figure 1.

Particle size distribution of CL-ML and CH soils.

2.2. Testing Methods

In this study, the experimental program included conventional direct shear testing to characterize shear strength behavior and the determination of the Soil–Water Characteristic Curve (SWCC) using an oedometer-type cell in combination with the contact filter paper method.

2.2.1. Conventional Direct Shear Test

The shear strength characterization of the tested soil was undertaken following the procedures outlined in ASTM D3080-23 [34]. Both total stress parameters (cohesion, c, and friction angle, ϕ) and effective stress parameters (c′, ϕ′) for saturated conditions were quantified. All experiments were performed under controlled room temperature and constant water content to eliminate external hydraulic boundary effects. After consolidation equilibrium was achieved under the designated net normal stresses, the specimens were sheared at a constant displacement rate of 1 mm/min. This rate was selected to allow dissipation of pore-air pressures while limiting pore-water drainage, thereby promoting a partially drained response in the air phase and an undrained response in the water phase. In addition, the termination criterion for the conventional direct shear test was defined as the point at which the shear stress stabilized after reaching its peak value. Owing to the very low saturated hydraulic conductivity () of the soil and the rapid rate of loading, the shear stage was interpreted within a constant water content framework.

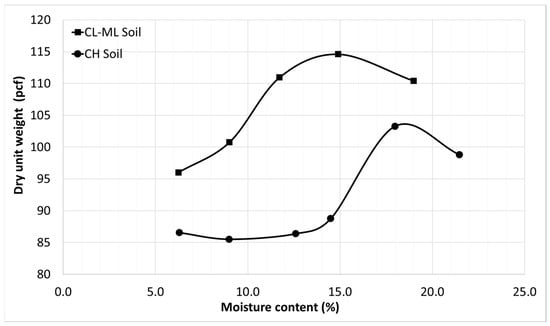

The experimental program included five moisture states for the CH soil and six moisture contents for the CL–ML soils. These conditions were selected to capture the effect of moisture variation on shear strength behavior. All specimens were compacted at the optimum moisture content (OMC: CL-ML soil = 14.4%, and CH soil = 18.5%) to 95% of the maximum dry density ( (Figure 2). Specimens on the dry side of OMC were prepared through controlled air-drying, while wet-of-OMC and saturated states were achieved by gradually adding water to the compacted samples, and letting them reach equilibrium condition. The corresponding gravimetric water content, degree of saturation, and matric suction values for each condition are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 2.

Compaction curves for CL-ML and CH soils.

Table 4.

Summary of moisture conditions adopted in the direct shear testing.

Normal stresses of 20, 40, and 80 kPa were applied during testing. For the driest specimens, an additional stress level of 60 kPa was included to further evaluate the shear response and to examine the linearity and reliability of the shear strength envelope. The selected stress levels were chosen to represent in-situ stress conditions under pavements and light construction buildings anticipated in the field.

2.2.2. Characterization of Unsaturated Hydraulic Behavior

The soil–water retention behavior was evaluated within a suction range of 0–1500 kPa using an oedometer-type cell under zero net normal stress [35]. Test specimens were reconstituted in stainless-steel rings measuring 63.2 mm in diameter and 25 mm in height and compacted to 95% of the maximum dry unit weight at OMC. Following compaction, the specimens were saturated for a period of 7–21 days. Drying was subsequently imposed by stepwise increments of pore-air pressure to 25, 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000, and 1400 kPa. At each increment, equilibrium was verified prior to recording matric suction and vertical deformation.

For suction levels beyond 1500 kPa, measurements were conducted in accordance with ASTM D5298-16 [36]. Whatman No. 42 filter paper was employed, with the contact method used for matric suction determination.

3. Results

3.1. Saturated Shear Strength Response

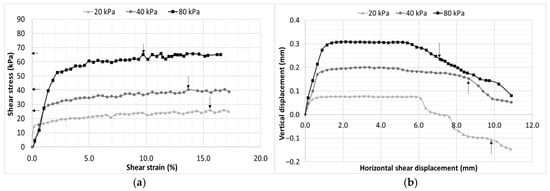

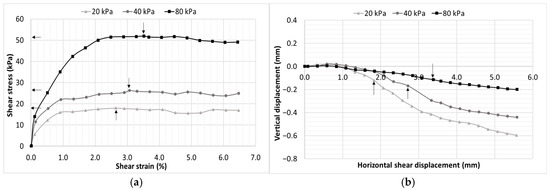

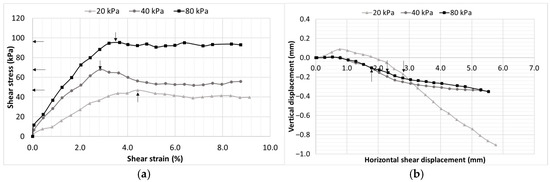

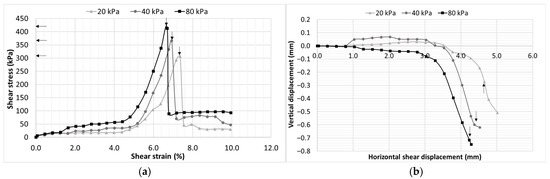

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present the results of single-stage direct shear tests conducted on the CL-ML soil and CH soil, respectively. The peak shear stresses and the corresponding strains at maximum shear stress for each net normal stress are indicated on the stress–strain curves using small arrowheads.

3.1.1. CL-ML Soil

The shear stress–strain relationships (Figure 3a) demonstrate a clear dependence of shear resistance on applied net normal stress, with peak shear stresses of 26 kPa, 41 kPa, 66 kPa for respective 20 kPa, 40 kPa, and 80 kPa net normal stresses. All specimens exhibit an initial linear stress–strain response, associated with elastic deformation and interparticle contact arrangement, followed by a nonlinear strain-hardening phase. For all specimens the peak strength was mobilized at higher shear strain of 10–16%.

The vertical–horizontal shear displacement response (Figure 3b) of the saturated CL-ML soil exhibits a pronounced dilative trend, indicative of a friction-dominated deformation mechanism for dense materials. An initial upward displacement is observed before the shearing, reflecting vertical expansion driven by particle rearrangement and interlocking within the shear zone. The magnitude of dilation increases with the net normal stress. At larger displacements, a gradual reduction in vertical movement is evident, likely associated with particle realignment and the progressive development of a localized shear band. Under low confinement, the response transitions from dilation to contraction during the shearing process. This behavior is usually observed on dense materials, and that might be the reason for the variability in the results. This has been observed by the various researchers [27,37].

Figure 3.

Shear response of saturated CL-ML soil: (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

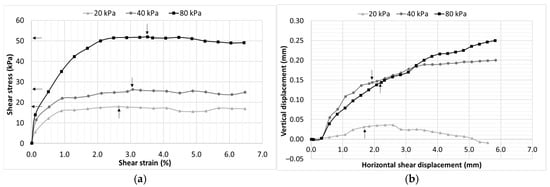

Figure 4.

Shear response of saturated CH soil: (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

3.1.2. CH Soil

Figure 4a presents the shear stress–strain response of the saturated CH soil under different net normal stresses. The curves show a continuous increase in shear stress with strain without a distinct peak for all confinement levels, indicating a ductile deformation response and gradual mobilization of shear resistance. For the specimen subjected to 80 kPa, as shearing progresses, the response transitions into a strain-softening phase, during which shear stress decreases slightly before stabilizing at a nearly constant residual value. The peak shear strength increases with the net normal stress, reaching approximately 18 kPa, 27 kPa, and 52 kPa under 20 kPa, 40 kPa, and 80 kPa confinement, respectively.

The vertical displacement–horizontal shear displacement response of the saturated CH soil (Figure 4b) exhibits a characteristic volumetric pattern influenced by confining stress and shear-induced structural changes. During the shearing, all three specimens show a slight contraction. Following this initial contraction, the specimens under 40 kPa and 80 kPa confinement transition into a dilative phase, with vertical displacement increasing progressively. In contrast, the specimen subjected to 20 kPa confinement shows initial dilation, however transitions back to contraction at larger displacements.

3.2. Unsaturated Shear Strength Response

Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 illustrate the results of single-stage direct shear tests performed on the CL-ML soil across five distinct moisture conditions, while Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 present the corresponding shear strength variations for the CH soil under four different moisture states. The moisture conditions representing the dry side of the OMC were achieved through a controlled air-drying process, whereas those on the wet side were prepared by gradual wetting to the target moisture levels. This systematic approach ensured consistent density across samples while enabling an independent assessment of the influence of moisture (suction stress) variation on the shear strength behavior of both soil types.

3.2.1. CL-ML Soil

The influence of moisture variation on the shear strength behavior of the CL-ML soil investigated corresponds to gravimetric moisture contents of 16%, 14.4% (OMC), 12%, 8%, and 6%, as shown in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, respectively. This range reflects the transition from near saturated to highly unsaturated conditions and provides insight into how matric suction influences the shear strength mobilization.

Figure 5.

CL-ML soil at 16% moisture content (78% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 6.

CL-ML soil at 14.4% moisture content (optimum moisture condition = 69% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 7.

CL-ML soil at 12% moisture content (57% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

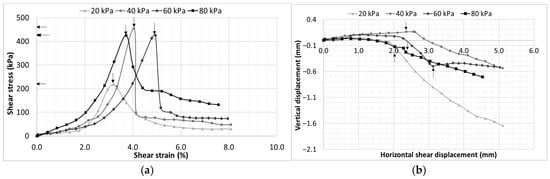

Figure 8.

CL-ML soil at 8% moisture content (39% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 9.

CL-ML soil at 6% moisture content (28% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

The shear stress–strain response exhibits a clear evolution with decreasing moisture content, reflecting the progressive influence of matric suction on shear strength development. At higher moisture contents (16% and 14.4%), the soil displays a strain-hardening behavior without a distinctly defined peak stress, indicating that shear strength mobilization is primarily governed by frictional resistance and particle interlocking with minimal suction contribution. As the soil begins to desaturate (12%), a significant shift occurs, with the development of a well-defined peak followed by strain softening. This behavior results from increased matric suction, which strengthens interparticle bonding prior to structural breakdown. A notable observation emerges at 12% moisture content, where the specimen subjected to a lower confinement stress of 20 kPa develops comparatively higher shear strength than the specimen under higher normal stress of 40 kPa. This can be attributed due to the dominant contribution of matric suction relative to mechanical confinement in this intermediate moisture range. The elevated suction enhances interparticle attraction, allowing the soil to mobilize greater shear resistance even under low overburden stress. At further reduced moisture contents (8% and 6%), where suction is substantially higher, the influence of net normal stress becomes less significant, and peak shear strengths for 40, 60, and 80 kPa converge to somewhat similar values. This convergence reflects a suction-controlled failure mechanism in which the contribution of the net normal stress to shear strength is minimized.

The vertical deformation response of the CL-ML soil shows a clear transition with decreasing moisture content. At moisture contents higher than optimum (16% and 14.4%), slight initial dilation occurs due to particle rearrangement, followed by contraction at larger shear displacements. At lower moisture contents (8% and 6%), the volumetric response changes notably, with a dilation phase observed before the shearing and after the shearing it was transitioned to contractive behavior.

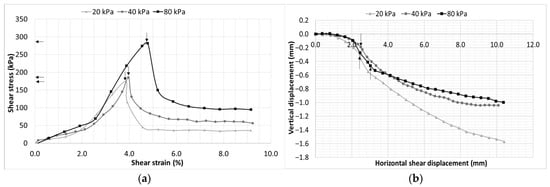

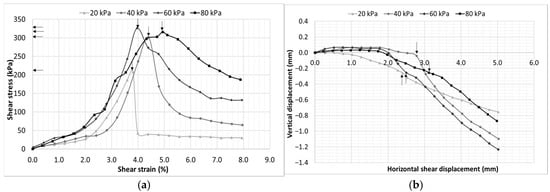

3.2.2. CH Clay

The influence of moisture variation on the unsaturated shear strength behavior of CH clay was examined by selecting four representative gravimetric moisture conditions of 5%, 10%, 18.5% (OMC), and 20%, ranging from highly unsaturated to near-saturated states.

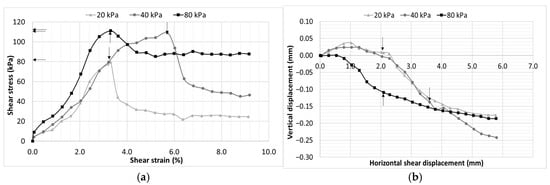

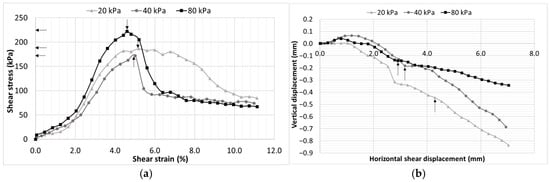

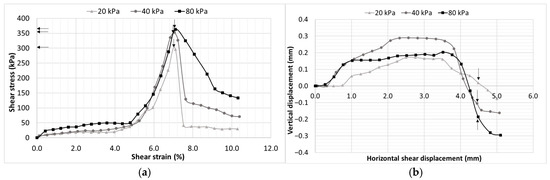

The shear stress–strain response exhibits a clear transition from strain-hardening behavior near saturation to a distinct peak-type response under unsaturated conditions. At 20% moisture content (Figure 10a), specimens subjected to 40 kPa and 80 kPa normal stresses mobilize similar shear strengths, indicating that suction effects are relatively minor and shear resistance is primarily governed by the confinment induced by the net normal stress. At the OMC (18.5%, Figure 11a), shear stress–strain behavior shows an characteristic response, the specimen under 20 kPa confinement develops higher shear strength compared with 40 kPa. As the moisture content decreases further (Figure 11a and Figure 12a), distinct peak behavior becomes evident across all normal stresses.

At near-saturated conditions (moisture content of 20%; Figure 10b), a slight dilative response was observed under low confining stresses (20 kPa and 40 kPa), whereas a contractive response developed under higher confinement during shearing. At a moisture content of 10%, the soil exhibited predominantly dilative behavior during shearing. However, as the soil transitioned to drier states (moisture content of 5%), the behavior shifted to a distinctly contractive response.

Figure 10.

CH soil at 20% moisture content (74% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 11.

CH soil at 18.5% moisture content (optimum moisture content = 40% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 12.

CH soil at 10% moisture content (23% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

Figure 13.

CH soil at 5% moisture content (12% degree of saturation), (a) shear stress–strain characteristics and (b) vertical deformation behavior.

The variability observed in the shear stress–net normal stress relationships for the mid-moisture ranges (Figure 6a, Figure 8a and Figure 10a) is likely attributed to inherent specimen-to-specimen differences. Statistical evaluation confirmed that these variations were not significant; therefore, all data obtained from the testing program are included for completeness. It is also noteworthy that the low-plasticity silty clay exhibits minimal shear resistance up to approximately 2–3% strain, while the highly plastic soil shows similarly limited resistance until about 5% strain. This initial behavior is consistent with the samples having been dried in place, a process that likely promoted the formation of shrinkage cracks around the specimens. During the early stages of shearing, the failure surface propagates through these pre-existing cracks, resulting in low measured resistance. Once the shear zone progresses beyond the cracked regions and engages the intact soil matrix, a marked increase in shear resistance becomes evident.

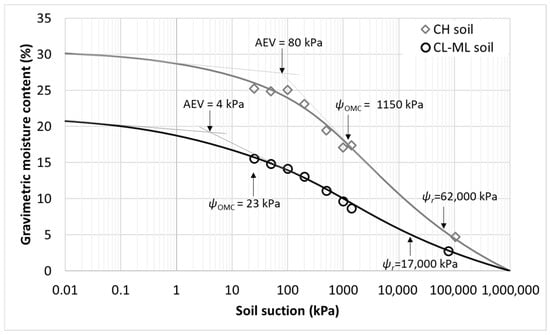

3.3. Soil–Water Characteristic Curve

The soil–water characteristic curves (SWCCs) of the CL-ML and CH soils were determined under controlled drying conditions to characterize their moisture retention behavior and suction-dependent hydraulic responses. Gravimatric water content was plotted against matric suction to capture the pore–water retention characteristics.

For both soils, the experimental data points were obtained using an oedometer-type pressure cell for low to intermediate suctions (0–1500 kPa) and the filter paper technique for higher suctions (>1500 kPa). Best-fit SWCCs were derived using the Fredlund and Xing (1994) [38] model (Equation (17)), and the corresponding curve-fitting parameters are summarized in Table 5.

where = volumetric water content at any suction; = saturated volumetric water content; e = natural number; = matric suction; a, n, m, and curve fitting parameters; and = correction factor.

Table 5.

Curve fitting parameters for investigated soils.

To ensure consistency across all datasets, the volumetric water content measurements were converted to gravimetric water content. This conversion, shown in Equation (19), allows for direct comparison with the gravimetric-based characterization used in the remaining analyses.

where = gravimetric water content; = density of water; = volumetric water content

The CL-ML soil exhibits a relatively low saturated gravimetric water content (≈21%) with a low AEV ≈ 4 kPa, and a residual suction of 17,000 kPa. In contrast, the CH soil displays a significantly higher saturated gravimetric water content (≈30%), a greater AEV (≈80 kPa), and considerably higher residual suction (~62,000 kPa) reflecting a finer pore structure and enhanced suction storage potential (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Soil–water characteristic curves for CL-ML and CH soils.

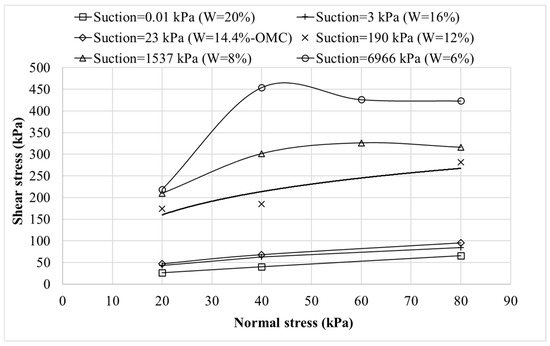

3.4. Influence of Soil Suction on Mohr-Coulomb Shear Strength Response

Figure 15 and Figure 16 present the Mohr–Coulomb failure shear strength envelopes derived from conventional direct shear tests performed on the CL-ML and CH soils, under saturated and unsatruated conditions. These envelopes were established using peak shear stress values obtained at net normal stress of 20 kPa, 40 kPa, 60 kPa (only for high suction values), and 80 kPa.

3.4.1. CL-ML Soil

Under saturated conditions (suction ≈ 0.01 kPa), the soil exhibits a linear shear strength response characterized by an effective cohesion of 13 kPa and an internal friction angle ( of 33° which approximately equals to the , consistent with classical Mohr–Coulomb behavior. As matric suction increases, however, the nature of the shear strength envelope becomes more nonlinear.

At relatively low suction levels (≤3 kPa), the envelope remains approximately linear, with a modest upward shift indicative of additional shear resistance provided by suction induced apparent cohesion. This behavior aligns with the soil–water retention characteristics of the material, as the air-entry value (AEV) is approximately 4 kPa. Once matric suction exceeds the AEV, the suction contributes significantly to shear strength nonlinearly, and the peak shear resistance becomes increasingly dependent on suction rather than solely on net normal stress. This transition is particularly evident at higher suction levels (e.g., 1537 kPa and 6966 kPa), where the shear strength envelope exhibits pronounced curvature. However, at higher suction levels combined with increased net normal stress, the measured shear stress tends to diminish or stay the same.

Figure 15.

Mohr–Coulomb envelope for CL-ML soil.

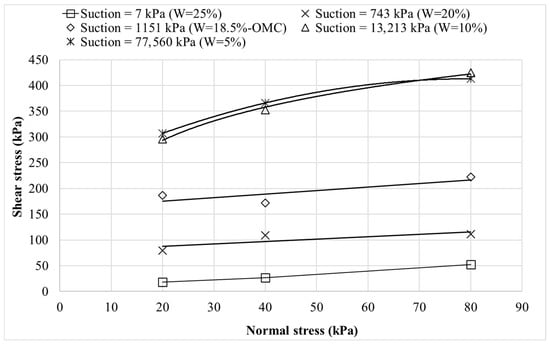

3.4.2. CH Soil

The evolution of the Mohr–Coulomb shear strength envelope for the CH soil (Figure 16) reveals a pronounced dependence on matric suction, with notable deviations from linearity as suction increases. Under saturated conditions (suction ≈ 7 kPa), the shear strength envelope exhibits a near-linear response characterized by an effective cohesion of 5 kPa and an internal friction angle of 30°. This linearity persists up to the measured AEV of 80 kPa, beyond which the envelope deviates from the classical Mohr–Coulomb form, reflecting the increasing contribution of the suction component to the shear strength.

At suction levels above the AEV (e.g., 743 kPa and 1151 kPa), the envelopes begin to exhibit curvature, though the degree of nonlinearity is less pronounced than that observed for the CL-ML soil within comparable suction ranges. This more gradual transition is likely associated with the higher clay fraction and greater suction retention capacity of the high plastic clayey soil. A distinct nonlinear response becomes evident at higher suction levels (e.g., 13,213 kPa and 77,560 kPa). At these suctions, the failure envelopes deviate from linearity, and the shear strength gain is increasingly governed by the suction stress and interparticle bonding rather than external confinement. Interestingly, the envelopes corresponding to the two highest suction levels display nearly identical trends across most of the stress range.

Figure 16.

Mohr–Coulomb envelope for CH soil.

3.5. Evaluation of Unsaturated Shear Strength with Suction

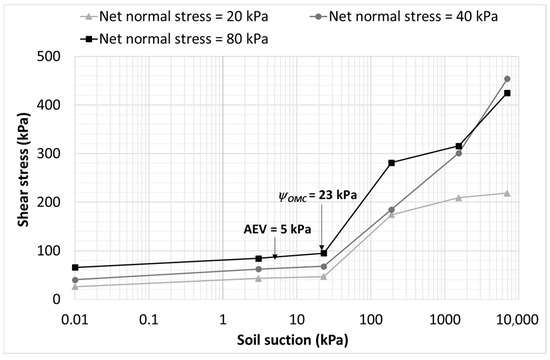

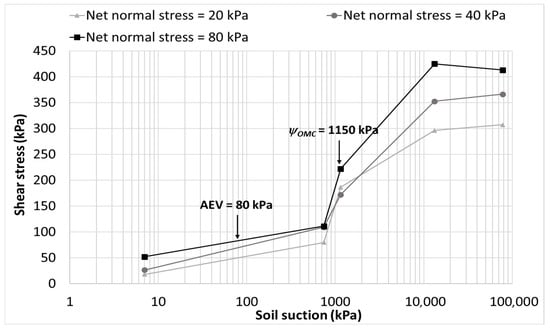

Figure 17 and Figure 18 present the variation in shear strength with soil suction for CL-ML and CH soils under various net normal stresses. Shear stress (kPa) is plotted against soil suction () (kPa) on a logarithmic scale to capture the progressive changes in shear strength from very low suction to high suction ranges.

3.5.1. CL-ML Soil

As shown in Figure 17, the CL-ML soil exhibits a distinct transition in shear strength behavior once matric suction exceeds its AEV of 4 kPa, shifting from a linear to a nonlinear trend as capillary effects become increasingly dominant. The suction corresponding to the OMC (ψOMC ≈ 23 kPa) marks the point where strength begins to rise more sharply as suction increases. All specimens were compacted at OMC and subsequently conditioned by air drying or rewetting to achieve dry- and wet-side moisture states, leading to notable differences in soil fabric and suction response. The air-dried specimens with high suction, representing the dry-of-optimum condition, developed an aggregated or flocculated structure with edge-to-face particle contacts and relatively large inter-aggregate pores. This open fabric facilitated continuous capillary menisci and stronger suction transfer across the shear plane, resulting in higher apparent cohesion and a steeper shear strength increase, particularly under greater confining stresses. In contrast, the wet of optimum specimens exhibited a more dispersed, face-to-face arrangement with smaller pore spaces and higher degrees of saturation, which reduced capillary continuity and limited the mobilization of suction-induced strength. Consequently, at net normal stresses of 40 kPa and 80 kPa, the soil displays a bi-linear trend with increases in shear strength with suction, except for a minor deviation near 200 kPa suction. At higher suction levels, both 40 kPa and 80 kPa specimens continue to gain strength, while the 20 kPa condition shows a slight reduction at extreme suctions, likely due to microcrack formation and partial fabric collapse induced by excessive desiccation.

Figure 17.

Variation in shear strength with soil suction for CL-ML soil.

3.5.2. CH Soil

Figure 18 presents the variation in shear strength with soil suction for the CH soil. Similarly to the CL-ML soil, the CH soil exhibits a distinct deviation from linearity once suction exceeds its AEV. The suction corresponding to the optimum moisture content (ψOMC ≈ 1150 kPa) represents a transitional state in which the soil structure contributes effectively to shear resistance. Beyond approximately 13,000 kPa, the rate of increase in shear strength with suction decreases slightly, this seems to be due to the breakdown of capillary bridges, microcrack development, and elastoplastic behavior of the soil [2,3].

Figure 18.

Variation in shear strength with soil suction for CH soil.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect of Net Normal Stress Variation on the Shear Strength of Unsaturated Soils

The shear strength of both CL–ML and CH soils increases consistently with net normal stress under all suction conditions, confirming that net normal stress (σ − ua) is the dominant variable governing shear resistance in unsaturated soils. This trend agrees with the classical framework proposed by Fredlund et al. [7] and experimentally verified by Escario and Sáez [24] and Gan et al. [25], which demonstrated a nearly linear relationship between shear strength and net normal stress. The increase in shear strength is more pronounced when the soil suction is below or near the AEV, where capillary forces interact effectively with the applied stress to enhance interparticle frictional resistance.

At the OMC corresponding to suctions of approximately 23 kPa for the CL–ML soil and 1150 kPa for the CH soil, the soil exhibits a transitional response. Within this range, both matric suction and net normal stress contribute substantially to shear strength development, reflecting a balanced interaction between capillary and frictional mechanisms. At higher suction levels, the effect of net normal stress becomes progressively less significant due to the reduction in capillary water and the corresponding decline in suction-induced cohesion. This nonlinear reduction in the rate of shear strength increase with suction is consistent with the findings of Vanapalli et al. [15], Lu and Likos [39], and Rahardjo et al. [40], who attributed this behavior to the diminished capillary contribution and transition toward adsorptive suction regimes.

4.2. Influence of Soil Suction Variation on Unsaturated Shear Strength Behavior over a Broad Suction Range

At lower suction ranges, that is, below the AEV, the contribution of matric suction to the shear strength is relatively minor compared with that of the net normal stress. Within this range, the angle ϕᵇ is approximately equal to the effective friction angle ϕ′ [2,3,14,25]. This behavior can be attributed to the near saturation of soil pores, where water menisci form between adjacent particles, resulting in a limited contribution of suction to the overall shear strength. As the suction exceeds the AEV, marking the onset of the transition zone, a substantial reduction in water content occurs, and the influence of suction becomes increasingly significant. Both soils investigated in this study exhibited a distinct deviation from linearity within this transition range, a trend consistent with the findings reported by several researchers [15,25,39,40,41].

Upon entering the residual suction range, the CL–ML soil exhibited a more pronounced increase in shear strength with increasing suction, particularly under higher net normal stresses. In contrast, the CH soil displayed an opposite response, likely attributable to the presence of adsorbed water and the physicochemical interactions characteristic of highly plastic clays [42].

Furthermore, when matric suction decreases and moisture content increases simultaneously, the shear strength attains its peak near the optimal moisture content ratio. This trend confirms that suction contributes most effectively when sufficient water is present to sustain capillary continuity without inducing full saturation. Beyond this optimal state, excessive suction or desaturation disrupts the water-film network and weakens interparticle bonding, leading to a gradual reduction in strength. The magnitude of the optimum water content, which is highly dependent on the proportion and mineralogy of fine particles, plays a critical role in controlling the linear to non-linear response of unsaturated soils to suction variation [42].

4.3. Development and Calibraton of a Nonlinear Equation for Predicting Unsaturated Shear Strength over Extended Suction Range

The experimental results indicate that the shear strength of unsaturated soils exhibits a distinctly nonlinear relationship with net normal stress, a behavior that becomes increasingly evident at higher suction levels. A comparable nonlinearity is also observed in the contribution of matric suction to the overall shear resistance. To capture this complex interaction between stress state and suction, a series of nonlinear regression analyses were performed using Excel on the experimental data, leading to the development of an empirical model capable of accurately reproducing the observed shear strength behavior over the entire suction range considered in this study. The proposed exponential model (Equation (20)) provided an excellent fit to the measured data, yielding a coefficient of determination (R2) of 0.93. The formulation of the exponential model is expressed as follows:

where is the effective cohesion under saturation condition, represents the net normal stress acting on the shear plane, and is the soil suction. The parameters of are general curve fitting parameters derived from the nonlinear regression of extensive experimental datasets encompassing soil with varying plasticity and fine content.

In this formulation, the first two terms, , describe the linear stress-dependent contribution to shear strength, reflecting the classical Mohr–Coulomb framework. The third term, , introduces an exponential suction-dependent component that captures the nonlinear influence of matric suction on shear strength. Here, represents the maximum suction-induced contribution to shear resistance, and is a fitting coefficient governing the rate of strength mobilization with increasing suction. The exponential form ensures that the model reproduces the fast initial increase in shear strength observed at low suctions (below the AEV) and the gradual attenuation of strength gain as suction continues to rise and desaturation progresses.

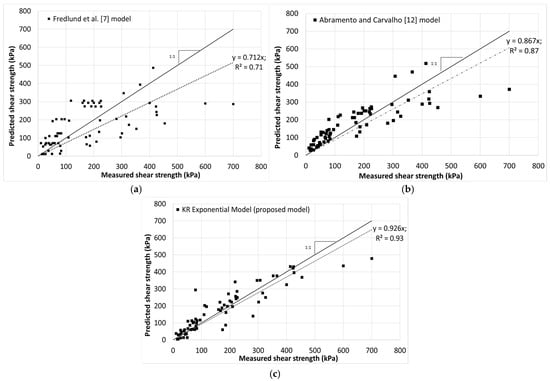

4.4. Validation of Proposed Nonlinear Shear Strength Model with Independet Data from the Literature

The data obtained in this study, together with the data obtained from the sources referenced in Table 3, was used to validate the model. Figure 19 shows a comparison between the measured and predicted shear strengths obtained using three different models: the linear model proposed by Fredlund et al. [8], the nonlinear Abramento and Carvalho [12] power-law model, and the proposed KR exponential model. The Fredlund et al. [8] model, which assumes a linear relationship between shear strength and matric suction, underestimates the experimental data at higher suction levels, yielding an R2 = 0.71. This linear formulation fails to capture the nonlinear strength gain that occurs as suction increases beyond the AEV. In contrast, the Abramento and Carvalho [12] power-law model (Equation (6) in Table 1) improves the fit with an R2 = 0.87, indicating that the nonlinear form more effectively represents the curvature observed in experimental results.

Finally, the proposed KR exponential model demonstrates the strongest correlation with the measured data (R2 = 0.93) and the least some of the squared errors, capturing both the initial rapid increase and the subsequent attenuation in shear strength over the full suction range. The improved agreement with experimental observations of the KR model arises from its exponential suction-dependent term, which allows for a gradual transition from net normal stress-controlled to suction-controlled behavior. This continuity ensures accuracy across a broad range of soil types and suction levels, overcoming the limitations of previous linear and power-law formulations. Consequently, the KR exponential model provides a more robust and physically consistent representation of the unsaturated shear strength envelope, particularly at elevated suction values where other models deviate from experimental observations.

Figure 19.

Comparison between measured and predicted shear strength for various models (a) Fredlund et al. [7] linear model, (b) Abramento and Carvalho [12] nonlinear model, (c) KR Exponential Model (proposed model).

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the combined effects of net normal stress and matric suction on the shear strength and vertical displacement with horizontal displacement behavior of unsaturated soils with different plasticity indices. A new nonlinear exponential equation was developed to predict unsaturated shear strength across an extended suction range. The experimental program, supported by regression analysis and model comparison, revealed the governing mechanisms of stress–suction interaction and the model’s enhanced predictive capability performance relative to existing formulations. The major conclusions drawn from this research are summarized below:

- 1.

- Nonlinearity of Unsaturated Shear Strength: The experimental results confirm that the shear strength of unsaturated soils varies nonlinearly with matric suction. Under high-suction conditions, the CL-ML soil exhibited an increasing rate of shear strength gain, whereas the CH soil showed a decreasing rate of strength enhancement. This contrasting response highlights the governing influence of soil plasticity and microstructural fabric on suction-dependent shear strength behavior. These findings reinforce the importance of incorporating suction-driven nonlinearity when evaluating the shear strength of unsaturated soils across a broad range of suction conditions.

- 2.

- Influence of Net Normal Stress on Unsaturated Shear Strength: Increasing net normal stress enhances shear resistance and stiffness while progressively suppressing dilation. However, at high suction levels and elevated confining pressures, the influence of net normal stress on shear strength becomes negligible. This reduction is likely associated with particle crushing and reorientation of soil fabric, leading to a decrease in the effective friction angle (ϕ), as reported by Mitchell and Soga [43]. Further, under higher net normal stress, the predicted shear strength was found to be underestimated relative to the lower net normal stress, consistent with the findings of Vanapalli et al. [15].

- 3.

- Influence of Matric Suction on Unsaturated Shear Strength: In the low-suction range where the soil remains nearly saturated, the suction strength parameter (ϕᵇ) approximates the effective friction angle (ϕ′), indicating a strong coupling between suction and effective stress. This behavior has been widely reported in the literature [2,3,14,25]. As matric suction exceeds the OMC, the contribution of suction to shear strength increases. For the low-plastic clay, the contribution increases, but for the plastic soil, the contribution reduces at high suction values. This variability reflects the complex interplay between soil plasticity, fine content, and microstructural rearrangement under changing suction conditions.

- 4.

- Validation of the Proposed Nonlinear Equation:The developed exponential model successfully integrates stress and suction-dependent mechanisms within a continuous, physically consistent framework. Regression-derived parameters, with an independent database collected from literature review, yielded an excellent fit (R2 = 0.93), demonstrating enhanced predictive capability across diverse soil types. The model accurately reproduces the nonlinear strength evolution and outperforms existing linear and power-law formulations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.E.Z.; methodology, K.R. and C.E.Z.; validation, K.R.; formal analysis, K.R. and C.E.Z.; investigation, K.R.; data curation, K.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.R.; writing—review and editing, C.E.Z.; supervision, C.E.Z.; project administration, C.E.Z.; funding acquisition, C.E.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Center for Infrastructure Transformation, U.S. Department of Transportation, USA, grant number 69A3552344813, sub-award number M2303851.

Data Availability Statement

All the data collected are presented in this manuscript. Validation studies data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain Escario, V. and Juca, J. [13], Vanapalli. S. K. et al. [15], Gan and Fredlund [33], and Zapata [32].

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Minnesota Department of Transportation and the Texas Department of Transportation for providing the soils tested in this research project. They also express their gratitude to Sravan Kumar Thandrangi, a graduate student worker, for his contribution in data collection during this study. During the preparation of this manuscript/study, the author(s) used Grammarly (EDU), and ChatGPT-5 for the purposes of check the spelling and grammar of the English language. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MnDOT | Minnesota Department of Transportation |

| TxDOT | Texas Department of Transportation |

| USCS | Unified Soil Classification System |

| AEV | Air Entry Value |

| OMC | Optimum Moisture Content |

| SWCC | Soil–Water Characteristic Curve |

| KR | Kalani Rajamanthri |

References

- Gulhati, S.K. Shear Strength of Partially Saturated Soils. Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund, D.G. Unsaturated soil mechanics in engineering practice. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 286–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Likos, W.J. Unsaturated Soil Mechanics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr, O. Abhandlungen aus dem Gebiete der Technischen Mechanic, 3rd ed.; Welhelm Ernst and Sohn: Berlin, Germany, 1914. [Google Scholar]

- Tresca, H.E. Memoire sur L’ecoulement des corps solids, Dans Memoires Present’ee par Divers Savants; Comptes Rendus Academy of Science: Paris, France, 1868; Volume 18, pp. 733–799. [Google Scholar]

- Mises, R.V. Mechanik der festen Körper im plastisch-deformablen Zustand. In Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen; Mathematisch Physikalische Klasse; Weidmannsche Buchh: Hildesheim, Germany, 1913; pp. 582–592. [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Morgenstern, N.R.; Widger, R.A. The shear strength of unsaturated soils. Can. Geotech. J. 1978, 15, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, A.W.; Alpan, I.; Blight, G.E.; Donald, I.B. Factors Controlling the Strength of Partly Saturated Cohesive Soils. In Proceedings of ASCE Research Conference on Shear Strength of Cohesive Soils, Boulder, CO, USA, 13–17 June 1960; pp. 503–532. [Google Scholar]

- Sridharan, A. Some Studies on the Strength of Partly Saturated Clays. Ph.D. Thesis, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Lamborn, M.J. A Micromechanical Approach to Modelling Partly Saturated Soils. Master’s Thesis, Texas A & M University, College Station, TX, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, R.W. Interpretation of triaxial compression test results on partially saturated soils. In Advanced Triaxial Testing of Soil and Rock; ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1988; pp. 512–538. [Google Scholar]

- Abramento, M.; Carvalho, C.S. Geotechnical Parameters for the Study of Natural Slope Instabilization at Serra do Mar-Brazilian Southeast. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 13–18 August 1989; Volume 3, pp. 1599–1602. [Google Scholar]

- Escario, V.; Juca, J. Strength and deformation of partly saturated soils. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 13–18 August 1989; Volume 1, pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Vanapalli, S.K.; Fredlund, D.G.; Pufahl, D.E.; Clifton, A.W. Model for the prediction of shear strength with respect to soil suction. Can. Geotech. J. 1996, 33, 379–392392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanapalli, S.K.; Fredlund, D.G.; Pufahl, D.E. The relationship between the soil-water characteristic curve and the unsaturated shear strength of a compacted glacial till. Geotech. Test. J. 1996, 19, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, L.; Liu, S.; Lai, Y. Research of soil–water characteristics and shear strength features of Nanyang expansive soil. Eng. Geol. 2002, 65, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsushi, Y.; Matsukura, Y. Cohesion of unsaturated residual soils as a function of volumetric water content. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2006, 65, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayadelen, C.; Sivrikaya, O.S.M.A.N.; Taşkıran, T.; Güneyli, H. Critical-state parameters of an unsaturated residual clayey soil from Turkey. Eng. Geol. 2007, 94, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, G.S.; Rahardjo, H.; Choon, L.E. Shear strength equations for unsaturated soil under drying and wetting. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2010, 136, 594–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyanaga, A.; Rahardjo, H. Unsaturated shear strength of soil with bimodal soil-water characteristic curve. Géotechnique 2019, 69, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Sun, D.A.; Zhou, A.; Li, J. Predicting shear strength of unsaturated soils over wide suction range. Int. J. Geomech. 2020, 20, 04019175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghadeh, R.A.; Toker, N.B. Exponential equation for predicting shear strength envelope of unsaturated soils. Int. J. Geomech. 2019, 19, 04019061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, O.M. A simplified procedure to estimate the shear strength envelope of unsaturated soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2006, 43, 1088–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escario, V.; Saez, J. The strength of partly saturated soils. Geotechnique 1986, 36, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, K.J.; Fredlund, D.G. Multistage direct shear testing of unsaturated soils. Geotech. Test. J. 1988, 11, 132–138138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, N.; Khabbaz, M.H. A unique relationship for the determination of the shear strength of unsaturated soils. Géotechnique 1998, 48, 681–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallipoli, D.; Gens, A.; Sharma, R.; Vaunat, J. An elasto-plastic model for unsaturated soils including the effect of suction hysteresis. Géotechnique 2003, 53, 123–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, E.E.; Gens, A.; Josa, A. A constitutive model for partially saturated soils. Géotechnique 1990, 40, 405–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, A.; Mongiovì, L.; Bosco, G. An experimental investigation on the shear strength of unsaturated soils. Can. Geotech. J. 2000, 37, 584–598. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D7928-21e1; Standard Test Method for Particle-Size Distribution (Gradation) of Fine-Grained Soils Using the Sedimentation (Hydrometer) Analysis. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4318-17e1; Standard Test Methods for Liquid Limit, Plastic Limit, and Plasticity Index of Soils. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- Zapata, C.E. Uncertainty in Soil-Water-Characteristic Curve and Impacts on Unsaturated Shear Strength Predictions. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, J.K.M.; Fredlund, D.G. Shear strength behavior of two saprolitic soils. In Unsaturated Soils, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Arid Solids, Paris, France, 6–8 September 1995; Alonso, E., Delage, P., Eds.; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 1995; pp. 71–76. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D3080/D3080M-23; Standard Test Method For Direct Shear Test of Soils Under Consolidated Drained Conditions. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.astm.org/d3080_d3080m-23.html (accessed on 21 September 2023).

- Padilla, J.M.; Perera, Y.Y.; Houston, W.N.; Fredlund, D.G.; Tarantino, A.; Romero, E.; Cui, Y.J. A new soil-water characteristic curve device. In Proceedings of the Advanced Experimental Unsaturated Soil Mechanics, EXPERUS, Trento, Italy, 27–29 June 2005; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D5298-16; Standard Test Method for Measurement of Soil Potential (Suction) Using Filter Paper. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2016.

- Holtz, R.D.; Kovacs, W.D.; Sheahan, T.C. An Introduction to Geotechnical Engineering; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1981; Volume 733. [Google Scholar]

- Fredlund, D.G.; Xing, A.; Huang, S. Predicting the permeability function for unsaturated soils using the soil-water characteristic curve. Can. Geotech. J. 1994, 31, 533–546546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, N.; Likos, W.J. Suction stress characteristic curve for unsaturated soil. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2006, 132, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahardjo, H.; Heng, O.B.; Leong, E.C. Shear strength of a compacted residual soil from consolidated drained and constant water content triaxial tests. Can. Geotech. J. 2004, 41, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheahan, T.C.; Ladd, C.C.; Germaine, J.T. Rate-dependent undrained shear behavior of saturated clay. J. Geotech. Eng. 1996, 122, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, T.A.; Sutman, M.; Medero, G.M. Validation, reliability, and performance of shear strength models for unsaturated soils. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2023, 41, 4271–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.K.; Soga, K.; O’Sullivan, C. Fundamentals of Soil Behavior; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.