The Geotourism Product—What It Is and What It Is Not

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Is there a difference between theoretical approaches and understandings of geoproducts and geotourism products, or can these terms be considered synonyms, referring to the same category?

- What are the key elements and features of a geotourism product?

2. Methods

3. Results: Geotourism, Geotourism Products, and Geoproducts

4. Discussion

4.1. What Is Not a Geotourism Product?

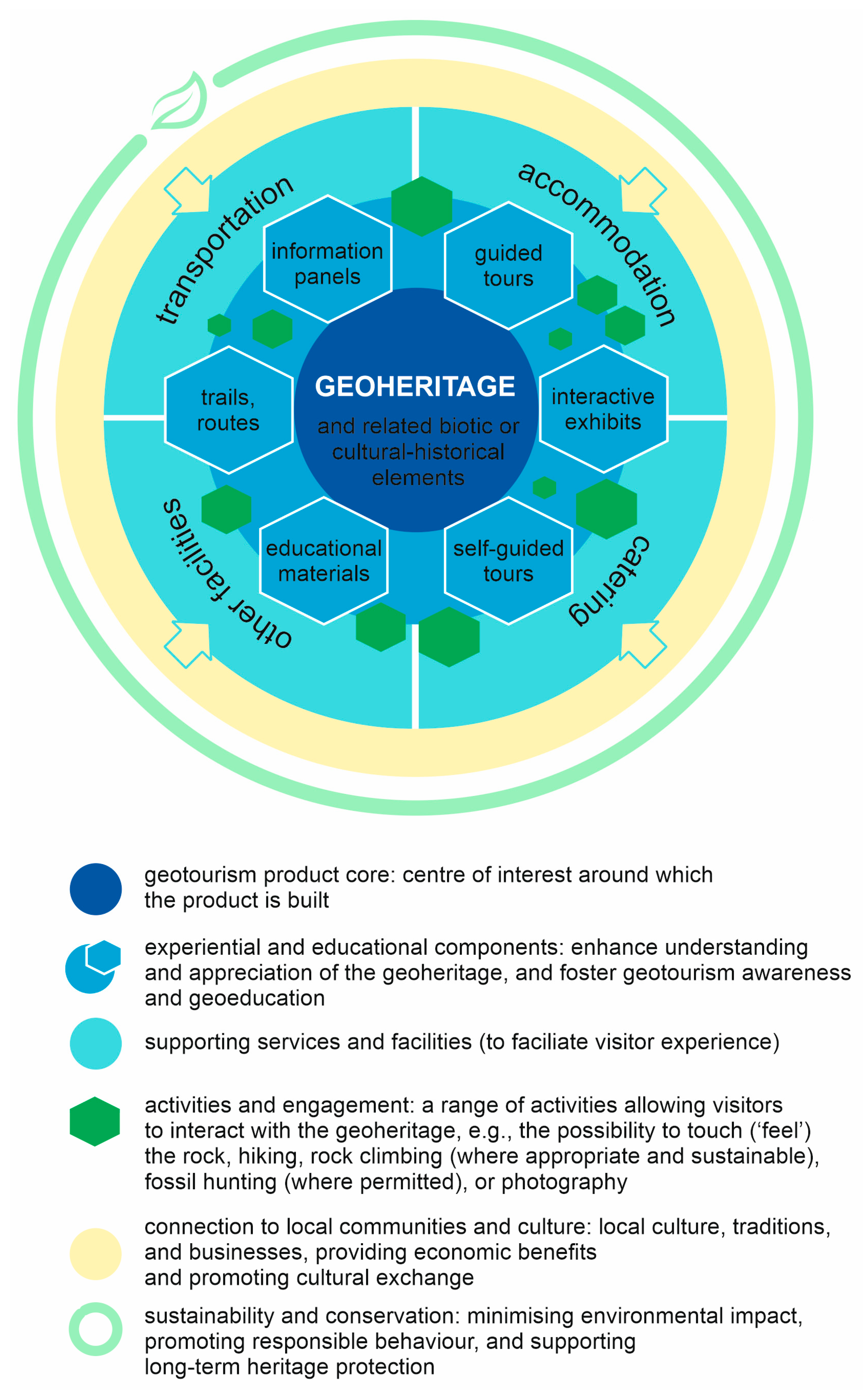

4.2. What Is a Geotourism Product?

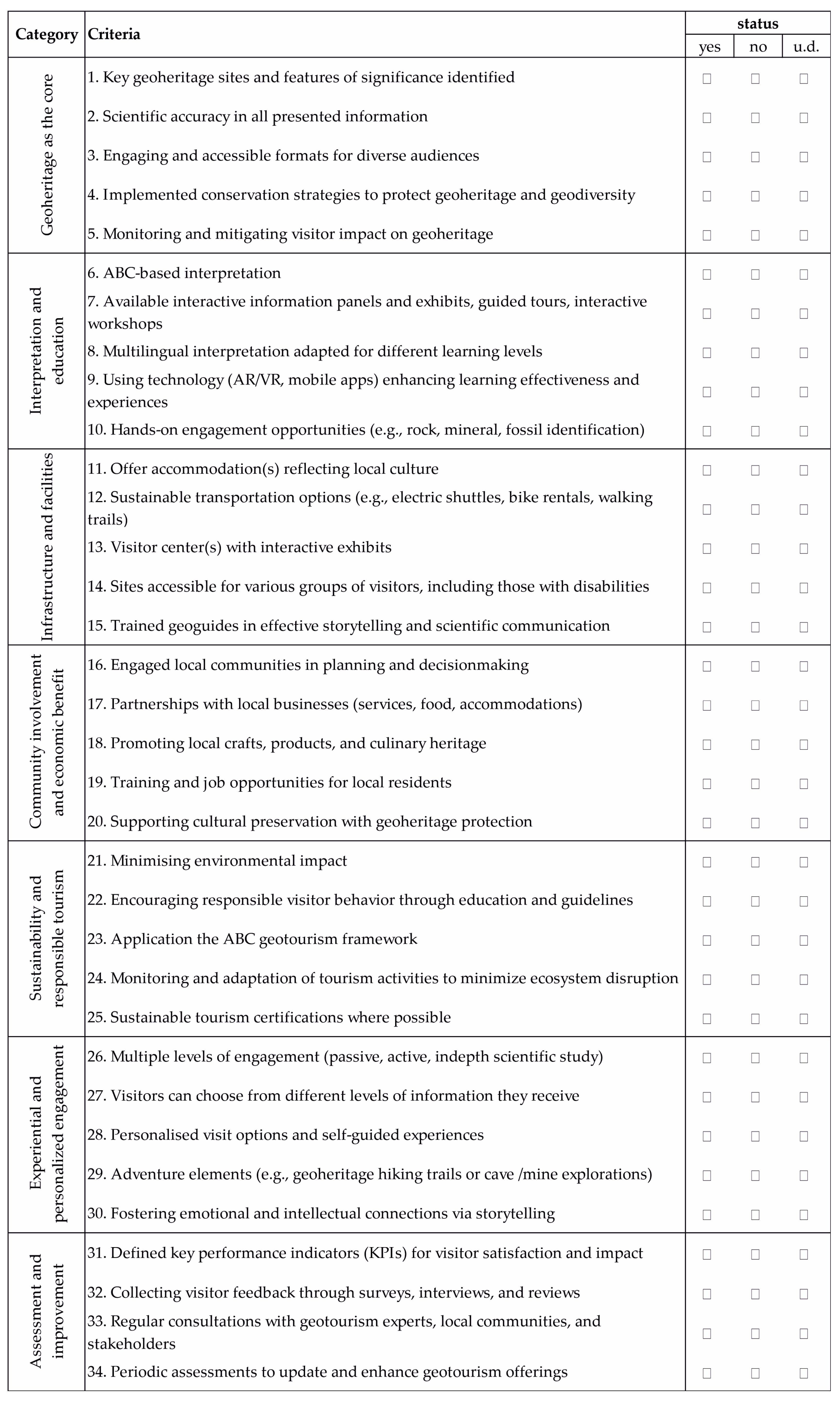

5. Geotourism Product Features

5.1. Core Elements of Geotourism and Its Development

5.2. Sustainability- and Community-Oriented Approaches

5.3. Implementation and Continuous Improvement

6. Conclusions

- Firstly, there is a significant deficiency in dedicated research articles explicitly addressing the precise definition and components of a geotourism product. The limited number of scholars who have engaged with this complex subject often fail to adequately consider both the unique and inherent characteristics of geotourism—an interplay of geological heritage and tourism—and the essential elements that comprehensively define a holistic tourism product. This notable gap in current academic discourse highlights the urgent need for more focused and interdisciplinary research to strengthen the theoretical foundations of geotourism product development.

- Secondly, it is essential to clearly distinguish between a singular object, service, facility, or event, often inaccurately labelled as “geoproducts.” This term frequently includes items such as handicrafts, decorative products, souvenirs, and even individual interpretive panels. While these items hold significant value and are typically inspired by geodiversity, they do not, on their own, constitute a comprehensive geotourism product. Instead, they serve as vital components or integral elements contributing to a larger, more intricate, and cohesive geotourism experience. Acknowledging this essential distinction is crucial for both theoretical rigour and the effective development and promotion of genuinely holistic geotourism products that provide a complete visitor experience.

- Ultimately, a crucial clarification emerges regarding the interaction between geotourism products and the broader implications of geotourism development activities, including the establishment of geoparks and geotourism visitor centres. These larger entities should not be viewed as geotourism products. More accurately, they should be understood as geographic areas or destinations where a variety of geotourism products and services can be created, offered, and consumed. Failing to properly define this distinction can lead to significant misconceptions. For instance, geoparks function as essential ecosystems that provide the context and resources necessary for geotourism products, rather than representing the products themselves. This intricate and clear understanding is essential for avoiding conceptual confusion and for establishing a strong foundation for future research, strategic planning, and effective development efforts within geotourism.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hose, T.A. Selling the story of Britain’s stone. Environ. Interpret. 1995, 10, 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Dowling, R.K. Geotourism’s Global Growth. Geoheritage 2011, 3, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hose, T.A. 3G’s for Modern Geotourism. Geoheritage 2012, 4, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K.; Newsome, D. Geotourism: Definition, characteristics and international perspectives. In Handbook of Geotourism; Dowling, R.K., Newsome, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham: UK, 2018; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ólafsdóttir, R.; Tverijonaite, E. Geotourism: A Systematic Literature Review. Geosciences 2018, 8, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadry, B.N. (Ed.) The Geotourism Industry in the 21st Century: The Origin, Principles, and Futuristic Approach, 1st ed.; Apple Academic Press: Burlington, ON, Canada, 2021; ISBN 9781771888264. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Global Geoparks. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/en/iggp/geoparks/about (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Smith, S.L. The tourism product. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 582–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.; Neto De Carvalho, C.; Ramos, M.; Ramos, R.; Vinagre, A.; Vinagre, H. Geoproducts—Innovative development strategies in UNESCO Geoparks: Concept, implementation methodology, and case studies from Naturtejo Global Geopark, Portugal. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2021, 9, 108–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, D.; Dowling, K.R. Setting an agenda for geotourism. In Geotourism: The Tourism of Geology and Landscape; Newsome, D., Dowling, R.K., Eds.; Goodfellow Publishers Limited: Oxford, UK, 2010; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNWTO Tourism Definitions. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284420858 (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Xu, J.B. Perceptions of tourism products. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 607–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto de Carvalho, C.; Rodrigues, J.C.; Canilho, S.; Amado, S. Geopark Naturtejo, bajo los auspicios de la UNESCO: La construcción participativa de un destino geoturístico en Portugal. Tierra Tecnol. 2011, 40, 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Douček, J.; Zelenka, J. New trends in geoproducts development: Železné Hory National Geopark Case Study. Czech J. Tour. 2018, 7, 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornecká, E.; Molokáč, M.; Gregorová, B.; Čech, V.; Hronček, P.; Javorská, M. Structure of Sustainable Management of Geoparks through Multi-Criteria Methods. Sustainability 2024, 16, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Geotourism Product as an Indicator for Sustainable Development in Poland. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molokáč, M.; Kornecká, E.; Tometzová, D. Proposal for Effective Management of Geoparks as a Tool for Sustainable Tourism in the Conditions of the Slovak Republic. Land 2024, 13, 1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komoo, I.; Azman, N.; Ahmad, N.; Ali, C.A.; Bukhari, A.M.M. An integrated geoproduct development for geotourism in Langkawi UNESCO Global Geopark: A case study of the Kubang Badak Biogeotrail. Geoheritage 2022, 14, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauknerova, E.; Sidlichovsky, P.; Urbanas, S.; Med, M. The European location framework—From national to European. In Proceedings of the International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Online, 12–19 July 2016; Volume XLI-B4, pp. 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, J.-E.F.M.; Shushkov, D.A.; Kurovics, E.; Tihtih, M.; Kotova, O.B.; Pala, P.; Gömze, L.A. Effect of composition and sintering temperature on thermal properties of zeolite-alumina composite materials. Építőanyag J. Silic. Based Compos. Mater. 2020, 72, 131–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, J.P. Geotextiles: The road ahead. In Civil Engineering, Supplement on Geotextiles and Geomembranes; 1986; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Allan, M.; Shavanddasht, M. Rural geotourists segmentation by motivation in weekends and weekdays. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2017, 19, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrikazemi, A.; Mehrpooya, A. Geotourism resources of Iran. In Geoheritage and Geotourism: A Global Perspective; Dowling, R.K., Newsome, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Basi Arjana, I.W.; Ernawati, M.; Astawa, I.K. Journal of Environmental Management & Tourism. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. 2019, 10, 1399–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Basi Arjana, I.W.; Ernawati, N.M.; Astawa, I.K. Journal of Physics: Conference Series. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 953, 012106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzezińska-Wójcik, T. Relationship between the Geotourism Potential and Function in the Polish Part of the Roztocze Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. Geosciences 2021, 11, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y. The importance of interpretation in promoting geotourism to the Daigu Landform. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csiki-Sava, Z.; Andrășanu, A. Meeting Island Dwarfs and Giants of the Cretaceous—The Hațeg Country UNESCO Global Geopark, Romania. Geoconservation Res. 2021, 4, 471–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dóniz-Páez, J.; Pérez, N.M.; Becerra-Ramírez, R.; Hernández-Ramos, W. Geotourism on an active volcanic island (La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain). Misc. Geogr. 2024, 28, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dryglas, D.; Miśkiewicz, K. Construction of the geotourism product structure on the example of Poland. In Proceedings of the 14th International Multidisciplinary Scientific Geoconference, Albena, Bulgaria, 17–26 June 2014; pp. 155–162. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca Filho, R.E.; Castro, P.d.T.A.; Varajão, A.F.D.C.; Figueiredo, M.d.A. Percepção dos visitantes do Parque Nacional da Serra do Cipó (MG) para o geoturismo. Anu. Inst. Geociênc. 2018, 41, 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, M.-L.; Schmitz, P.; Weber, J. Messel Pit UNESCO World Heritage fossil site in the UGGp Bergstraße-Odenwald, Germany– challenges of geoscience popularization in a complex geoheritage context. Geoconservation Res. 2021, 4, 524–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Zabielska, M. New Geoeducational Facilities in Central Mazovia (Poland) Disseminate Knowledge about Local Geoheritage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halim, M.H.A.; Said, M.Z.; Ali, M.A.; Masnan, S.S.K.; Talib, N.K.; Saidin, M. The impressive of geological evidence of Kuala Muda district: A proposal for geotourism products in Kedah, Malaysia. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2024, 56, 1637–1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, W.; Dóniz-Páez, J.; Pérez, N.M. Urban Geotourism in La Palma, Canary Islands, Spain. Land 2022, 11, 1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutagalung, P.M.; Nasution, Z.; Rujiman; Ginting, N. The role of geological relationship and brand of geoproduct on regional development in Samosir Island of Geopark Caldera Toba with mediating method. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2024, 52, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chingombe, W.; Taru, P. Rural geotourism as an option for development in Phuthaditjhaba: Golden Gate National Park area, South Africa. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2018, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Chybiorz, R.; Kowalska, M. Inwentaryzacja i ocena atrakcyjności geostanowisk województwa śląskiego. Przegląd Geol. 2017, 65, 365–374. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, P.; Wibowo, D.A.; Raharjo, P.D.; Lestiana, H.; Puswanto, E. The great Sumatran fault depression at West Lampung district, Sumatra, Indonesia as geomorphosite for geohazard tourism. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2023, 47, 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kneć, A.; Zgłobicki, W. Mobile Applications as a Tool for Tourism Management in Geoparks (Case Study: Potential Geopark Małopolski Przełom Wisły, E Poland). Land 2025, 14, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compľová, M. The identification of geoproducts in the village of Jakubany as a basis for geotourism development. Acta Geoturistica 2010, 1, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Miśkiewicz, K. Produkt geoturystyczny jako narzędzie geoedukacyjne i metoda promocji dziedzictwa geologicznego Polski. Przegląd Geol. 2023, 71, 314–320. [Google Scholar]

- Modrej, D.; Fajmut Štrucl, S.; Hartmann, G. Results of the geointerpretation research in the frame of the Danube GeoTour project. Geologija 2018, 61, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munajat, M.; Avenzora, R.; Darusman, D.; Basuni, S. Optimization of edu—Tourism through geotourism development strategy in Mount Slamet and Serayu mountainous areas, Central Java Province. In AIP Conference Proceedings, Proceedings of The Third International Conference on Innovation in Education (ICoIE 3): Digital Transformation in Education, Padang, Indonesia, 20–21 November 2021; American Institute of Physics: College Park, MD, USA, 2023; Volume 2805, p. 040017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakonechnykh, V.; Zhuravleva, M.; Sivkova, A.; Volokhova, S. The impact of the territorial marketing on highlighting the brand “Baikal” in the Baikal region. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2019, 27, 1271–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norrish, L.; Sanders, D.; Dowling, R. Geotourism product development and stakeholder perceptions: A case study of a proposed geotrail in Perth, Western Australia. J. Ecotourism 2014, 13, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pásková, M.; Zelenka, J.; Ogasawara, T.; Zavala, B.; Astete, I. The ABC Concept—Value Added to the Earth Heritage Interpretation. Geoheritage 2021, 13, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.K. Global geotourism—An emerging form of sustainable tourism. Czech J. Tour. 2013, 2, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poros, M.; Sobczyk, W. Rewitalizacja terenu pogórniczego po kopalni surowców skalnych na przykładzie kamieniołomu Wietrznia w Kielcach. Rocz. Ochr. Sr. 2013, 15, 2369–2380. [Google Scholar]

- Reynard, E.; Kaiser, C.; Martin, S.; Regolini, G. An application for geosciences communication by smartphones and tablets. In Engineering Geology for Society and Territory—Volume 8; Lollino, G., Giordan, D., Marunteanu, C., Christaras, B., Yoshinori, I., Margottini, C., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 259–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Regolini-Bissig, G.; Perret, A.; Kozlik, L. Élaboration et évaluation de produits géotouristiques. Téoros 2010, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Buckingham, T.; Martin, S.; Regolini, G. Geoheritage, geoconservation and geotourism in Switzerland. In Landscapes and Landforms of Switzerland. World Geomorphological Landscapes; Reynard, E., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 571–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoffelen, A. Where is the community in geoparks? A systematic literature review and call for attention to the societal embedding of geoparks. Area 2020, 52, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šambronská, K.; Matušíková, D.; Šenková, A.; Kormaníková, E. Geotourism and its sustainable products in destination management. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2023, 46, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. Some Comments to Geosite Assessment, Visitors, and Geotourism Sustainability. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, G.A.; van der Borg, J.; Van Rompaey, A.; Van Passel, S.; Adgo, E.; Minale, A.S.; Asrese, K.; Frankl, A.; Poesen, J. Benefit Segmentation of Tourists to Geosites and Its Implications for Sustainable Development of Geotourism in the Southern Lake Tana Region, Ethiopia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutin, T. Error tracking in Ikonos geometric processing using a 3D parametric model. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2003, 69, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashalova, N.N.; Ermolaev, V.A.; Ruban, D.A. The Hosta’s Labyrinth on the Black Sea Shore: A Case Study of “Selling” Geosites to the Lay Public. Heritage 2023, 6, 7083–7099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliawati, A.K.; Rofaida, R.; Gautama, B.P.; Aryanti, A.N. Coffee as geo-product of a small island geopark increasing livelihood in a local community-A study in Belitung Island. Afr. J. Hosp. Tour. Leis. 2019, 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Yuliawati, A.K.; Rofaida, R.; Gautama, B.P.; Hadian, M.S.D. Geoproduct development as part of geotourism at Geopark Belitong. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018); Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 110–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuliawati, A.K.; Rofaida, R.; Gautama, B.P.; Millah, R.S.; Aryanti, A.N.; Hadian, M.S.D. Strategies for business sustainability through digital marketing and innovation in aspiring geopark. Geo J. Tour. Geosites 2025, 58, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, H.T.P.; Hai, H.Q.; Nam, N.T.Q. Proposing Geo-Products for Ly Son Geopark, Vietnam. Proceedings 2018, 2, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geotourism for UNESCO Global Geoparks: A Toolkit for Developing and Managing Tourism. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000391228.locale=en (accessed on 12 January 2025).

- Interreg Danube Transnational Programme. Danube GeoTour. Available online: https://dtp.interreg-danube.eu/uploads/media/approved_project_output/0001/31/5b9ae43fb7274d1c44e1aff7f5c3425983e9e8d9.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Miśkiewicz, K. Promoting geoheritage in geoparks as an element of educational tourism. In Geotourism: Organization of the Tourism and Education in the Geoparks in the Middle-Europe Mountains; Szponar, A., Toczek-Werner, S., Eds.; University of Business in Wrocław: Wroclaw, Poland, 2016; pp. 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kubalíková, L. Assessing Geotourism Resources on a Local Level: A Case Study from Southern Moravia (Czech Republic). Resources 2019, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmi, L.; Coratza, P.; Gauci, R.; Soldati, M. Geoheritage as a Tool for Environmental Management: A Case Study in Northern Malta (Central Mediterranean Sea). Resources 2019, 8, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgłobicki, W.; Kukiełka, S.; Baran-Zgłobicka, B. Regional Geotourist Resources—Assessment and Management (A Case Study in SE Poland). Resources 2020, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antić, A.; Mihalović, D.; Radović, P.; Tomić, N.; Marjanovivić, M.; Radaković, M.; Marković, S.B. Assessing speleoarcheological geoheritage: Linking new Paleolithic discoveries and potential cave tourism destinations in Serbia. Int. J. Geoheritage Parks 2022, 10, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A.; Mikhailenko, A.V.; Yashalova, N.N. Valuable geoheritage resources: Potential versus exploitation. Resour. Policy 2022, 77, 102665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Vravcová, A.; Podoláková, M.; Varcholová, L.; Kršák, B. Linking Geoheritage or Geosite Assessment Results with Geotourism Potential and Development: A Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, A.R.; Dar, F.A.; Ahmad, M.Z. Characteristics of Geosites for Promotion and Development of Geotourism in Ladakh, India. Geoheritage 2023, 15, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tešić, D.; Tomić, T.; Tomić, N.; Marković, S.B.; Tadić, E.; Marković, R.; Bačević, N.; Davidović Manojlović, M. Using LiDAR Technology for Geoheritage Inventory and Modelling: Case Study of Đavolja Varoš Geosite (Serbia). Geoheritage 2024, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashalova, N.N.; Ruban, D.A. Geoheritage Value of Three Localities from Kislovodsk in the Southern Central Ciscaucasus: A Resource of Large Resort Area. Geosciences 2024, 14, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubalíková, L.; Vandelli, V.; Pál, M. New horizons in geodiversity and geoheritage research: Bridging science, conservation, and development. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2025, 33, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louz, E.; Rais, J.; Barakat, A.; El Baghdadi, M. Identification of Potential Areas for the Development of Geotourism in the Northern Part of the M’goun Geopark (Morocco) Using Multi-Criteria Analysis and Sig. Geoheritage 2025, 17, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brocx, M.; Semeniuk, V. The 8Gs—A blueprint for Geoheritage, Geoconservation, Geo-education and Geoutourism. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 66, 803–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiropoulos, G.; Drinia, H.; Antonarakou, A.; Zouros, N. From Geoheritage to Geoeducation, Geoethics and Geotourism: A Critical Evaluation of the Greek Region. Geosciences 2021, 11, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palgutová, S.; Štrba, Ľ. Geoheritage of the Precious Opal Bearing Zone in Libanka Mining District (Slovakia) and Its Geotourism and Geoeducation Potential. Land 2022, 11, 2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štrba, Ľ.; Palgutová, S. Geoheritage Interpretation Panels in UNESCO Global Geoparks: Recommendations and Assessment. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppoloni, S.; Di Capua, G. The Meaning of Geoethics. In Ethical Challenges and Case Studies in Earth Sciences; Wyss, M., Peppoloni, S., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Koupatsiaris, A.A.; Drinia, H. Expanding Geoethics: Interrelations with Geoenvironmental Education and Sense of Place. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macadam, J. Geoheritage: Getting the message across. What message and to whom? In Geoheritage—Assessment, Protection, and Management; Brilha, J., Reynard, E., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migoń, P. Geo-interpretation: How and for whom? In Handbook of Geotourism; Dowling, R.K., Newsome, D., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2018; pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crofts, R. Improving Visitors’ Geoheritage Experience: Some Practical Pointers for Managers. Geoheritage 2024, 16, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdowsi, S.; Tavana, M.; Heydari, R.; Štrba, Ľ. Geoeducation: The key to geoheritage conservation in tourism destinations. Int. Geol. Rev. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European UNESCO Geoparks Travel Guide. Available online: https://www.globalgeoparksnetwork.org/sites/default/files/2025-03/BookletGeoparks_0.pdf (accessed on 1 April 2025).

| Author(s) | WOS | Scopus | Reference to Geotourism Product/Geoproduct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allan and Shavanddasht [22] | no | yes | Geotourism is considered a tourism product, and rural tourism a geotourism product. |

| Amrikazemi and Mehtpooya [23] | no | yes | Authors only refer to an Alisdar Cave visit to be a geotourism product. |

| Basi Arjana et al. [24] | no | yes | The research is focused on geotourism attractions as specific aspects of tourism products with no broader reference to (geo)tourism product theory. |

| Basi Arjana et al. [25] | no | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Brzezińska-Wójcik [26] | yes | yes | The authors characterise various products, referring to the conception of Rodrigues et al. [9] |

| Cai et al. [27] | yes | yes | The article mentions “geotourism product” in its acknowledgements only. |

| Csiki-Sava and Andrășanu [28] | yes | yes | The authors mention the development of several unique geoproducts, including, e.g., House of Rocks, the House of Science and Art, or dinostops, without mentioning any specific theoretical framework. |

| Dóniz-Páez et al. [29] | no | yes | Geotourism products are mentioned, however, without any theoretical background, referring to visiting volcanic areas. |

| Dryglas and Miśkiewicz [30] | yes | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Fonseca Filho et al. [31] | no | yes | The authors mention “geotourism product” in terms of geotourism development; the paper focuses on geopark visitor profiles. |

| Frey et al. [32] | no | yes | The article mentions geotourism products in its abstract but does not discuss them in the main text. |

| Giroud [21] | no | yes | An article dealing with geotechnical engineering, not related to geotourism. |

| Górska-Zabielska [33] | yes | yes | Geological resources, either naturally unveiled or anthropogenically altered for visibility, are considered geotourism products (such as erratic boulders and lapidaries with geotourism infrastructure). |

| Halim et al. [34] | no | yes | With no theoretical basis, the article discusses tourism packages and some (potential) (geo)tourism products in the form of specific locations. |

| Hernández et al. [35] | yes | yes | The authors refer to geotourism products via proposed urban geo-itineraries without providing a theoretical background in geotourism products or geoproducts. |

| Hutagalung et al. [36] | no | yes | The authors discuss specific geoproducts in Samosir Island (Toba Caldera Geopark) according to the theory of Basi Arjana [25] and Rodrigues et al. [9] |

| Chingombe and Taru [37] | no | yes | The authors consider rural geotourism as a geotourism product. In this case, it is more appropriate to use the term “subset” rather than “product”. |

| Chybiorz and Kowalska [38] | no | yes | Not related to the topic of geotourism products or geoproducts; only in the abstract do the authors state that “the most valuable geosites of the Silesian Voivodeship should be protected and/or open to the public as geotourism products”. |

| Ibrahim et al. [20] | yes | no | An article dealing with zeolite properties, not related to geotourism. |

| Iqbal et al. [39] | no | yes | The article mentions geotourism products only in its introduction as a result of a specific approach to understanding geotourism, without specifying them in any detail. |

| Kneć and Zgłobicki [40] | yes | yes | An article introducing a mobile application as a geotourism product according to Rodrigues et al. [9] and Miśkiewicz [16]. |

| Komoo et al. [18] | yes | yes | The article characterises geoproducts in Langkawi UGGp, adopting the theoretical approach of Rodrigues et al. [9] and Compľová [41]. |

| Kornecká et al. [15] | no | no | Geoparks are defined as geotourism products (or products of geotourism). |

| Miśkiewicz [16] | no | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Miśkiewicz [42] | yes | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Modrej et al. [43] | no | yes | The authors mention the geotourism product in the abstract and conclusion; however, the paper deals with geointerpretation. |

| Molokáč et al. [17] | no | yes | Geoparks are defined as geotourism products. |

| Munajat et al. [44] | no | yes | Geotourism products are mentioned in relation to geotourism development. |

| Nakonechnykh et al. [45] | no | yes | Not related to geotourism or geotourism products. |

| Norrish et al. [46] | no | yes | The authors consider geotrails to be a geotourism product. |

| Pásková et al. [47] | yes | yes | The authors state that a geotourism product, according to Dowling (2013) [48], embeds geoconservation, communicates and promotes geological heritage, and helps build sustainable communities through appropriate economic benefits. Geotourism products and geoproducts are considered to be the same. |

| Pauknerova et al. [19] | yes | yes | An article dealing with GIS, not related to geotourism. |

| Poros and Sobczyk [49] | yes | yes | The authors name Checiny–Kielce and The Holy Cross Arecho Geological Trail as geotourism products. |

| Reynard et al. [50] | no | yes | A practical application of the framework proposed by Martin et al. 2010 [51]. |

| Reynard et al. [52] | no | yes | The article mentions geotourist interpretation products only. |

| Rodrigues et al. [9] | no | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Stoffelen [53] | no | yes | Discusses the role and position of geoparks and highlights the need to move beyond the realm of the geosciences to create new and meaningful insights into their societal role. |

| Šambronská et al. [54] | no | yes | The authors discuss/characterise geotourism products as introduced by Basi Arjana et al. |

| Štrba et al. [55] | no | yes | The authors mention geotourism products in terms of effective geotourism development based on the selected geosite assessment method. |

| Tessema et al. [56] | yes | yes | The term “geotourism products” is mentioned only in terms of tourist segmentation. |

| Toutin [57] | no | yes | An article dealing with GIS, not related to geotourism. |

| Yashalova et al. [58] | yes | yes | Characterisation of a specific geosite linked to various aspects, including mentioning some geoproducts, e.g., geofood. |

| Yuliawati et al. [59] | no | yes | Key article to consider. |

| Yuliawati et al. [60] | yes | no | Key article to consider. |

| Yuliawati et al. [61] | no | yes | The paper presents survey results on how digital marketing can contribute to the innovation of geoproducts. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Štrba, Ľ.; Palgutová, S.B.; Derco, J.; Kršák, B.; Sidor, C. The Geotourism Product—What It Is and What It Is Not. Geosciences 2025, 15, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15070270

Štrba Ľ, Palgutová SB, Derco J, Kršák B, Sidor C. The Geotourism Product—What It Is and What It Is Not. Geosciences. 2025; 15(7):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15070270

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠtrba, Ľubomír, Silvia Bodzáš Palgutová, Ján Derco, Branislav Kršák, and Csaba Sidor. 2025. "The Geotourism Product—What It Is and What It Is Not" Geosciences 15, no. 7: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15070270

APA StyleŠtrba, Ľ., Palgutová, S. B., Derco, J., Kršák, B., & Sidor, C. (2025). The Geotourism Product—What It Is and What It Is Not. Geosciences, 15(7), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15070270