Rapid Evaluation of Coastal Sinking and Management Issues in Sayung, Central Java, Indonesia

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Develop and demonstrate a rapid, open access, remote-sensing-based method to identify the drivers of coastal sinking in Sayung Sub-district, Central Java;

- (2)

- Quantitatively validate these findings using ground-based measurements and uncertainty analysis;

- (3)

- Assess the extent to which evidence-based recommendations for coastal management can be derived from such analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Data

- Level-2 Landsat 5 data acquired on 14 July 1997 and Level-2 Landsat 9 data acquired on 16 July 2024. All satellite data were obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) through the Earth Explorer data platform (https://earthexplorer.usgs.gov accessed on 25 September 2024). Each selected image underwent a standard preprocessing workflow before the analysis, such as radiometric and atmospheric corrections. The projection of the data was WGS 84/UTM Zone 49 S. The year 1997 marked the onset of land conversion for aquaculture, driven by the demand of the global market.

- Additional data include tidal gauge record data based on the K1 tidal projection model up to 2024 provided by the Geospatial Information Agency of Indonesia (Badan Informasi Geospasial—BIG) (https://srgi.big.go.id accessed on 10 October 2023). The K1 tidal constituents are closely related to the dynamics of shoreline changes. Diurnal variations are caused by the gravitational pull of the moon and the sun. Tidal data play a crucial role in projecting the extent of tidal flooding in coastal areas.

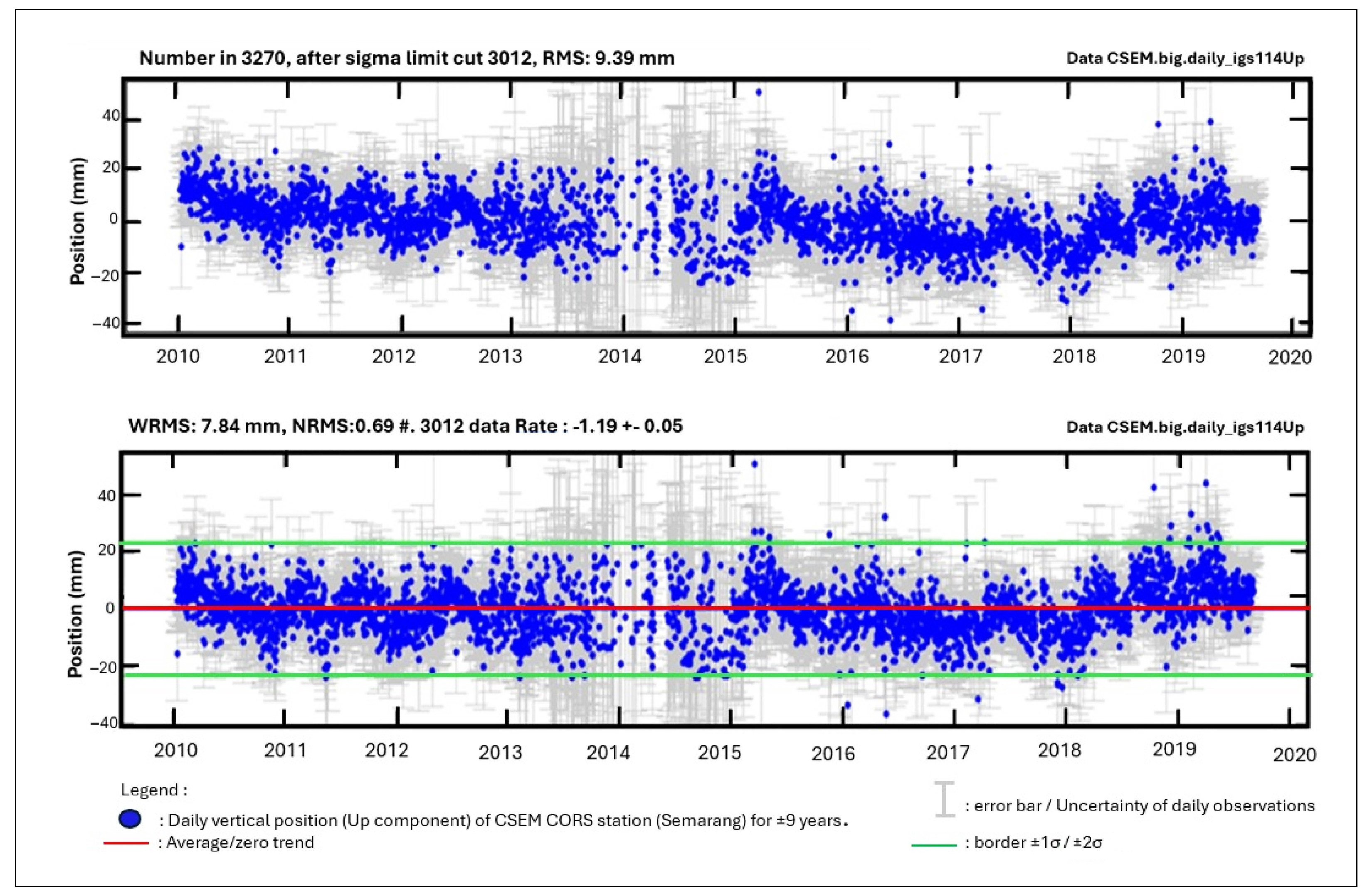

- Furthermore, Global Positioning System (GPS) data from the Continuously Operating Reference Station (CORS) network, specifically covering the Sayung region and its vicinity, were obtained from BIG (2024), also from the same platform of tidal data (https://srgi.big.go.id accessed on 12 Agust 2024). GPS data play a crucial role by enabling precise monitoring of land subsidence; mapping shoreline changes caused by erosion, sedimentation, or inundation; and supporting accurate modeling of tidal height when integrated with gauge data.

2.2.2. Data Processing

- A.

- Coastal change analysis

- The WMNDWI is selected as it is considered the most effective method for monitoring shoreline changes and land subsidence due to its enhanced accuracy in distinguishing water from non-water features. By incorporating the SWIR band, MNDWI provides higher sensitivity to water bodies compared to the NIR used in the standard NDWI, making it particularly suitable for complex coastal and urban environments. SWIR effectively reduces reflectance from built-up areas and vegetation, minimizing misclassification and ensuring clearer detection of inundated areas. Additionally, MNDWI excels in identifying small-scale changes in water extent and shoreline dynamics, enabling detailed monitoring of erosion, accretion, and gradual submersion due to sea-level rise or land subsidence. However, in this case, we use the WMNDWI to access more accurate information about the water changes.

- LSWI helps to detect persistent surface moisture, waterlogged soil conditions, and hydrological stress associated with land subsidence in low-lying regions. The calculation uses NIR and SWIR bands.

- NDVI helps to monitor changes in vegetation cover, which could indicate shifts in the environment due to coastal environmental change or flooding. The calculation is made using Visible red and NIR bands.

- Land surface change analysis using index differencing method

- B.

- Training data and ground truth

- C.

- Machine learning classification analysis

- (1)

- Using an MCDA framework, the indices were combined with specific weights, depending on the significance of each index in the analysis. Since the sinking cities phenomenon heavily considers changes in water bodies, WMNDWI was assigned greater importance compared to NDBI and NDVI, as represented in the formula below:

- (2)

- Unsupervised machine learning approach: The core of the classification process involved implementing a supervised machine learning model to distinguish between land change dynamics associated with coastal sinking. However, this method applied an unsupervised approach to explore patterns of spectral change in the absence of labeled training data in order to obtain faster results and in the absence of training data. The unsupervised method was applied to the multi-band composite raster constructed from four spectral indices using K-means clustering due to its computational efficiency. The number of clusters (k) was observed at k = 4, then each resulting cluster was spatially interpreted and assigned a semantic meaning based on its spectral signature, such as the following:

- Increase in WMNDWI and LSWI: change to water;

- Increase in NDBI and decline in NDVI: change to built-up area;

- Increase in LSWI and decline in NDVI: potential change to water;

- Increase in NDVI and decline in WMNDWI and LSWI: possible change to vegetation or stable land.

- D.

- Evaluation metric

- E.

- The analysis of the root causes of sinking coasts

- F.

- Review of adaptation and mitigation

3. Results

- Recently inundated or water-encroached zones;

- Vegetation-to-built-up transitions (urban sprawl);

- Stable land cover;

- Drying or reclaimed areas.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- Multi-temporal Landsat analysis (1997–2024), validated by tidal gauge and GPS data, reveals marked vegetation loss, persistent inundation, and urban expansion.

- Land subsidence averages 6.0 ± 0.8 cm/year, with model accuracy of 91%—confirming the robustness of the rapid evaluation approach.

- Combined spectral indices and machine learning provide strong evidence of hydrological encroachment, with built-up areas transitioning to waterlogged or submerged states.

- Rigorous groundwater extraction controls;

- Land-use zoning to limit development in high-risk areas;

- Systematic mangrove restoration and hybrid protection infrastructure;

- Ongoing geospatial monitoring to enable adaptive governance and early warning.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMA | Associated Mangrove Aquaculture |

| BIG | Badan Informasi Geospasial |

| CORS | Continuously Operating Reference Station |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| LSWI | Land Surface Water Index |

| MCDA | Multiple-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| MSS | Multi-Spectral Scanner |

| NDBI | Normalized Difference Built-up Index |

| NDVI | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index |

| NIR | Near Infra Red |

| OLI | Operational Land Imager |

| RTKLib | Real-Time Kinematics Library |

| RTRW | Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah/Regional Spatial Planning Document/Spatial Plan |

| SWIR | Short-Wave Infrared |

| TM | Thematic Mapper |

| USGS | United States Geological Survey |

| WMNDWI | Weighted Modified Normalized Difference Water Index |

References

- Jaligot, R.; Chenal, J. Stakeholders’ Perspectives to Support the Integration of Ecosystem Services in Spatial Planning in Switzerland. Environments 2019, 6, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.; Gunasiri, C. Impact of Coastal Land Use Change on Shoreline Dynamics in Yunlin County, Taiwan. Environments 2014, 1, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicin-Sain, B.; Belfiore, S. Linking marine protected areas to Integrated Coastal and Ocean Management: A Review of Theory and Practice. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2005, 48, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, K.; Barbee, M.; Thompson, P.; Fletcher, C. Coastal land subsidence accelerates timelines for future flood exposure in Hawai’i. Commun. Earth Environ. 2025, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, L.; Giarola, A.; Korff, M.; Lambert, J.; Meisina, C. Comprehensive database of land subsidence in 143 major coastal cities around the world: Overview of issues, causes, and future challenges. Front. Earth Sci. 2024, 12, 1351581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilo, S.; Salman, R.; Hermawan, W.; Widyaningrum, R.; Wibowo, S.T.; Lumban-Gaol, Y.A.; Meilano, I.; Yun, S.H. GNSS land subsidence observations along the northern coastline of Java, Indonesia. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, H.; Xu, Z.; Lin, G.; Lin, Y.; Liang, X.; Ling, J.; Wee, A.K.S.; Lin, H.; Zhou, Y.; et al. Coastal urbanization may indirectly positively impact the growth of mangrove forests. Commun. Earth Environ. 2024, 5, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ideki, O.; Ajoku, O. Scenario Analysis of Shorelines, Coastal Erosion, and Land Use/Land Cover Changes and Their Implication for Climate Migration in East and West Africa. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solihuddin, T.; Husrin, S.; Salim, H.L.; Kepel, T.L.; Mustikasari, E.; Heriati, A.; Ati, R.N.A.; Purbani, D.; Mbay, L.O.N.; Indriasari, V.Y.; et al. Coastal erosion on the north coast of Java: Adaptation strategies and coastal management. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 777, 012035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustan, A.; Ito, T.; Purwana, R.; Ardiyanto, R.; Santosa, B.H.; Sadmono, H. Time Series InSAR for Ground Deformation Observation in the Semarang Area, Central Java. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th Asia-Pacific Conference on Synthetic Aperture Radar (APSAR), Bali, Indonesia, 23–27 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaussard, E.; Amelung, F.; Abidin, H.; Hong, S.H. Sinking cities in Indonesia: ALOS PALSAR detects rapid subsidence due to groundwater and gas extraction. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 128, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwiakram, N.; Amarrohman, F.J.; Prasetyo, Y. Studi Penurunan Muka Tanah Menggunakan Dinsar Tahun 2017–2020 (Studi Kasus: Pesisir Kecamatan Sayung, Demak). J. Geod. Undip 2021, 10, 269–276. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, B.; Wicaksono, N.A.B.; Karmila, M.; Ridlo, M.A. Analysis of community adaptation to sinking coastal settlements in the Sriwulan, Demak Regency, Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1116, 012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutrisno, D.; Rahadiati, A.; Bin Hashim, M.; Shih, P.T.; Qin, R.; Helmi, M.; Yusmur, A.; Zhang, L. Spatial Planning-based ecosystem adaptation (SPBEA) as a Method to Mitigate the Impact of Climate Change: The Effectiveness of Hybrid Training and participatory workshops during a Pandemic in Indonesia. APN Sci. Bull. 2022, 12, 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solecki, W.; Friedman, E. At the Water’s Edge: Coastal Settlement, Transformative Adaptation, and Well-Being in an Era of Dynamic Climate Risk. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2021, 42, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkens, G.; Bucx, T.; Dam, R.; De Lange, G.; Lambert, J. Sinking Coastal Cities. Proc. IAHS 2015, 372, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, H.; Esteban, M.; Mikami, T.; Pratama, M.B.; Valenzuela, V.P.B.; Avelino, J.E. People’s perception of Land Subsidence, Floods, and Their Connection: A Note Based on Recent Surveys in a sinking coastal community in Jakarta. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2021, 211, 105753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Church, J.A.; White, N.J. Sea-Level Rise from the Late 19th to the Early 21st Century. Surv. Geophys. 2011, 32, 585–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelle, B.; Guillot, B.; Marieu, V.; Chaumillon, E.; Hanquiez, V.; Bujan, S.; Poppeschi, C. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of Shoreline Change of a 280-km High-energy disrupted sandy coast from 1950 to 2014: SW France. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2018, 200, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonneijck, F.; Van der Goot, F.; Pearce, F. Building with Nature in Indonesia: Restoring an Eroding Coastline and Inspiring Action at Scale; Wetlands International and Ecoshape Foundation: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Buffardi, C.; Ruberti, D. The Issue of Land Subsidence in Coastal and Alluvial Plains: A Bibliometric Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, L.T.M.; Su, J.; Wang, Q.; Stringer, L.C.; Switzer, A.D.; Gasparatos, A. Meta-analysis indicates better climate adaptation and mitigation performance of hybrid engineering-natural coastal defense measures. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 2870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Usha, S.; Alabdulkreem, E.; Alruwais, N.; Almukadi, W.S. Monitoring land subsidence using Sentinel-1A, persistent scatterer InSAR, and machine learning techniques. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 2025, 155, 105433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzner, J.; Strunz, G.; Martinis, S.; Plank, S. Analyzing coastal dynamics by means of multi-sensor satellite imagery at the East Frisian Island of Langeoog, Germany. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roukounis, C.N.; Tsoukala, V.K.; Tsihrintzis, V.A. An Index-Based Method to Assess the Resilience of Urban Areas to Coastal Flooding: The Case of Attica, Greece. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetri, T.K. NDVI, NDBI, and NDWI calculation using LANDSAT 7 and 8. GeoWorld Geomat. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 2, 32–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rudiarto, I.; Handayani, W.; Wijaya, H.B.; Insani, T.D. Land resource availability and climate change disasters in the rural coastal areas of Central Java—Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 202, 012029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemilang, W.A.; Wisha, U.J.; Solihuddin, T.; Arman, A.; Ondara, K. Sediment Accumulation Rate in Sayung Coast, Demak, Central Java Using Unsupported 210Pb Isotope. Atom Indonesia 2020, 46, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiyah, S.; Rindarjono, M.G.; Muryani, C. Analisis Perubahan Permukiman dan Karakteristik Permukiman Kumuh Akibat Abrasi dan Inundasi di Pesisir Kecamatan Sayung Kabupaten Demak Tahun 2003–2013. J. GeoEco 2015, 1, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Pramudito, W.A.; Suprijanto, J.; Soenardjo, N. Perubahan Luasan Vegetasi Mangrove di Desa Bedono Kecamatan Sayung Kabupaten Demak Tahun 2009 dan 2019 Menggunakan Citra Satelit Landsat. J. Mar. Res. 2020, 9, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irsadi, A.; Martuti, N.K.T.; Abdullah, M.; Hadiyanti, L.N. Abrasion and Accretion Analysis in Demak, Indonesia Coastal for Mitigation and Environmental Adaptation. Nat. Environ. Poll. Technol. 2022, 21, 633–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosma, R.H.; Debrot, A.O.; Tonneijck, F.H.; Rejeki, S. Technical Guidance: Associated Mangrove Aquaculture Farms; Building with Nature to Restore Eroding Tropical Muddy Coasts; Ecoshape: Amersfoort, The Netherlands, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mahroini, Z. Local Government Managament and Local Communty Mitigation of Tidal Flooding in Sayung Sub-District Demak Regency, Central Java Province, Indonesia. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/352978073_Local_Government_Managament_and_Local_Communty_Mitigation_ff_Tidal_Flooding_in_Sayung_Sub-District_Demak_Regency_Central_Java_Province_Indonesia (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Marfai, M.A.; Rahayu, E.; Triyanti, A. The Role of Local Wisdom and Social Capital in Disaster Risk Reduction and Development of Coastal Area; Gadjah Mada University Press: Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sutrisno, D.; Darmawan, M.; Rahadiati, A.; Helmi, M.; Yusmur, A.; Hashim, M.; Shih, P.T.Y.; Qin, R.; Zhang, L. Spatial-Planning-Based Ecosystem Adaptation (SPBEA): A Concept and Modeling of Prone Shoreline Retreat Areas. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chughtai, A.H.; Abbasi, H.; Karas, I.R. A review on change detection method and accuracy assessment for land use land cover. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 22, 100482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Xue, Q.; Xing, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, F. Remote Sensing Image Interpretation for Coastal Zones: A Review. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 4701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidayat, T.A.; Helmi, M.; Widada, S.; Satriadi, A.; Setiyono, H.; Ismanto, A.; Yusuf, M. Pengolahan Data Satelit Sentinel-1 dan Pasut untuk Mengkaji Area Genangan Akibat Banjir Pasang di Kecamatan Sayung, Kabupaten Demak. Indones. J. Oceanogr. 2020, 2, 306–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashok, A.; Rani, H.P.; Jayakumar, K.V. Monitoring of dynamic wetland changes using NDVI and NDWI based landsat imagery. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2021, 23, 100547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillesand, T.M.; Kiefer, R.W.; Chipman, J.W. Remote Sensing and Image Interpretation; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, G.; Chen, S.; Liu, K.; Wang, W.; Hou, H.; Gao, L.; Zhang, F.; Su, H. Spatiotemporal Variation in Sensitivity of urban vegetation growth and Greenness to vegetation water content: Evidence from Chinese Megacities. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 905, 167090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Wang, Z.F.; Cheng, W.C. A Review on land subsidence caused by Groundwater Withdrawal in Xi’an, China. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 2851–2863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H. Modification of normalised difference water index (NDWI) to enhance open water features in remotely sensed imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2006, 27, 3025–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Cheng, Q.; Peng, H.; Altan, O.; Li, Y.; Ara, I.; Huq, E.; Ali, Y.; Saleem, N. Review of Spectral Indices for Urban Remote Sensing. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2021, 87, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z. Empirical Examinations of Whether Rural Population Decline Improves the Rural Eco-Environmental Quality in a Chinese Context. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. NDWI—A normalized difference water index for Remote Sensing of vegetation liquid water from Space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, H.; Wang, D.; Sun, Y.; Qin, Y.; Wang, K.; Han, Y.; Tang, J.; Qiao, W. Spatiotemporal dynamics of the normalized difference vegetation index and its multidimensional drivers in a rapidly urbanizing coastal city: A case study of Lianyungang, China (2000−2023). Ecol. Inform. 2025, 91, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, K.; Srikanth, P.; Chakraborty, A.; Choudhary, K.; Ramana, K.V. Response of crop water indices to soil wetness and vegetation water content. Adv. Space Res. 2024, 73, 1316–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumban-Gaol, J.; Sumantyo, J.T.S.; Tambunan, E.; Situmorang, D.; Antara, I.M.O.G.; Sinurat, M.E.; Suhita, N.P.A.R.; Osawa, T.; Arhatin, R.E. Sea Level Rise, Land Subsidence, and Flood Disaster Vulnerability Assessment: A Case Study in Medan City, Indonesia. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triana, K.; Wahyudi, A.J. Sea Level Rise in Indonesia: The Drivers and the Combined Impacts from Land Subsidence. ASEAN J. Sci. Technol. Dev. 2020, 37, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Y.; Gao, J.; Ni, S. Use of normalized difference built-up index in automatically mapping urban areas from TM imagery. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, N.N.; Angiuli, E.; Gamba, P.; Gaughan, A.; Lisini, G.; Stevens, F.R.; Tatem, A.J.; Trianni, G. Multitemporal settlement and population mapping from Landsat using Google Earth Engine. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2015, 35, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, H.Z.; Andreas, H.; Gumilar, I.; Sidiq, T.P.; Fukuda, Y. Land subsidence in coastal city of Semarang (Indonesia): Characteristics, impacts, and causes. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2013, 4, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taftazani, R.; Kazama, S.; Takizawa, S. Spatial Analysis of Groundwater Abstraction and Land Subsidence for Planning the Piped Water Supply in Jakarta, Indonesia. Water 2022, 14, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, B.D. Land subsidence and earth fissures in south-central and southern Arizona, USA. Hydrogeol. J. 2016, 24, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiana, R.; Pigawati, B. Suitability of Location and Reach of Industrial Pollution in Sayung District, Demak Regency. Tek. PWK (Perenc. Wil. Kota) 2018, 7, 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- Murdohardono, D.; Tobing, T.M.H.L.; Sayekti, A. Overpumping of Groundwater as One of the Causes of Seawater Inundation in Semarang City. In Proceedings of the International Symposium and Workshop on Current Problems in Groundwater Management and Related Water Resources Issues, Bali, Indonesia, 3–8 December 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muskananfola, M.R.; Febrianto, S. Spatio-temporal analysis of shoreline change along the coast of Sayung Demak, Indonesia using Digital Shoreline Analysis System. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 34, 101060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Vidal, M.; Muñoz-Perez, J.J.; Contreras, A.; Contreras, F.; Lopez-Garcia, P.; Jigena, B. Increase in the Erosion Rate Due to the Impact of Climate Change on Sea Level Rise: Victoria Beach, a Case Study. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfai, M.A.; King, L. Potential vulnerability implications of coastal inundation due to sea level rise for the coastal zone of Semarang city, Indonesia. Environ. Geol. 2008, 54, 1235–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekar, K.; Sesha Sai, M.V.R.; Roy, P.S.; Dwevedi, R.S. Land Surface Water Index (LSWI) response to rainfall and NDVI using the MODIS Vegetation Index product. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 3987–4005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasin, M.Y.; Abdullah, J.; Noor, N.M.; Yusoff, M.M.; Noor, N.M. Landsat observation of urban growth and land use change using NDVI and NDBI analysis. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1067, 012037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Change Category | Area (km2) |

|---|---|

| To water | 71,233 |

| To built-up | 8467 |

| Potentially to water | 9970 |

| To vegetated | 5979 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sutrisno, D.; Dimyati, R.D.; Shofiyati, R.; Prihanto, Y.; Hidayat, J.T.; Darmawan, M.; Agus, S.B.; Helmi, M.; Sadmono, H.; Anggraini, N. Rapid Evaluation of Coastal Sinking and Management Issues in Sayung, Central Java, Indonesia. Geosciences 2025, 15, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120455

Sutrisno D, Dimyati RD, Shofiyati R, Prihanto Y, Hidayat JT, Darmawan M, Agus SB, Helmi M, Sadmono H, Anggraini N. Rapid Evaluation of Coastal Sinking and Management Issues in Sayung, Central Java, Indonesia. Geosciences. 2025; 15(12):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120455

Chicago/Turabian StyleSutrisno, Dewayany, Ratih Dewanti Dimyati, Rizatus Shofiyati, Yosef Prihanto, Janthy Trilusianthy Hidayat, Mulyanto Darmawan, Syamsul Bahri Agus, Muhammad Helmi, Heri Sadmono, and Nanin Anggraini. 2025. "Rapid Evaluation of Coastal Sinking and Management Issues in Sayung, Central Java, Indonesia" Geosciences 15, no. 12: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120455

APA StyleSutrisno, D., Dimyati, R. D., Shofiyati, R., Prihanto, Y., Hidayat, J. T., Darmawan, M., Agus, S. B., Helmi, M., Sadmono, H., & Anggraini, N. (2025). Rapid Evaluation of Coastal Sinking and Management Issues in Sayung, Central Java, Indonesia. Geosciences, 15(12), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/geosciences15120455