Abstract

Nature-based tourism is stimulated by the aesthetic properties of landscapes, and particular elements of the latter determine the overall scenic beauty. Big stones on forested mountain slopes are among such elements. The Partisan Glade geosite-based tourist destination ofthe Western Caucasus in southwestern Russia is distinguished by the occurrence of such stones. Their field investigation (measurements of physical parameters and interpretation of the common criteria of tourist-meaningful beauty) shows that these are essentially blocks (clasts with the size of 1–10 m) of all grades (fine, medium, and coarse blocks) and colluvial origin. The blocks influence on such parameters of scenic beauty as scale, condition, balance, diversity, shape, and uniqueness, and, therefore, these blocks are of aesthetic value. The most important is color and size. Apparently, the presence of these big stones stimulates tourists’ positive emotions. It is recommended to avoid block removal or breaking in the course of road maintenance.

1. Introduction

Landscape beauty (scenic beauty) is a significant attractor of tourists [1,2,3]. As a result, the aesthetic properties of landscapes and their particular elements (landforms, rocks, rivers, trees, etc.) have to be examined whenthe tourism potential of a given area is assessed. Such studies are also necessary for an understanding of the perspectives of individual tourism directions like geotourism [4]. It should be stressed that beauty perception is strongly related to tourists’ preferences and physical characteristics of landscapes [5,6]. If so, both should become subjects of investigation. In regard to the above-said, the ongoing rise of geotourism, the global geopark movement, and geodiversity concepts [4,7,8,9,10,11] have made urgent consideration of spectacular geological features with their specific aesthetic properties among key natural tourist attractions. This is especially the case of natural landscapes dominated by unique geological features. In other words, geological features are landscape elements and their presence diversifies landscape view and influences on its beauty. However, the aesthetic value of such features is far from being fullyunderstood, and this issue is studied rarely. Filling the noted gap is of practical importance because the relevant knowledge leads to an understanding of tourist satisfaction and effective destination promotion and management.

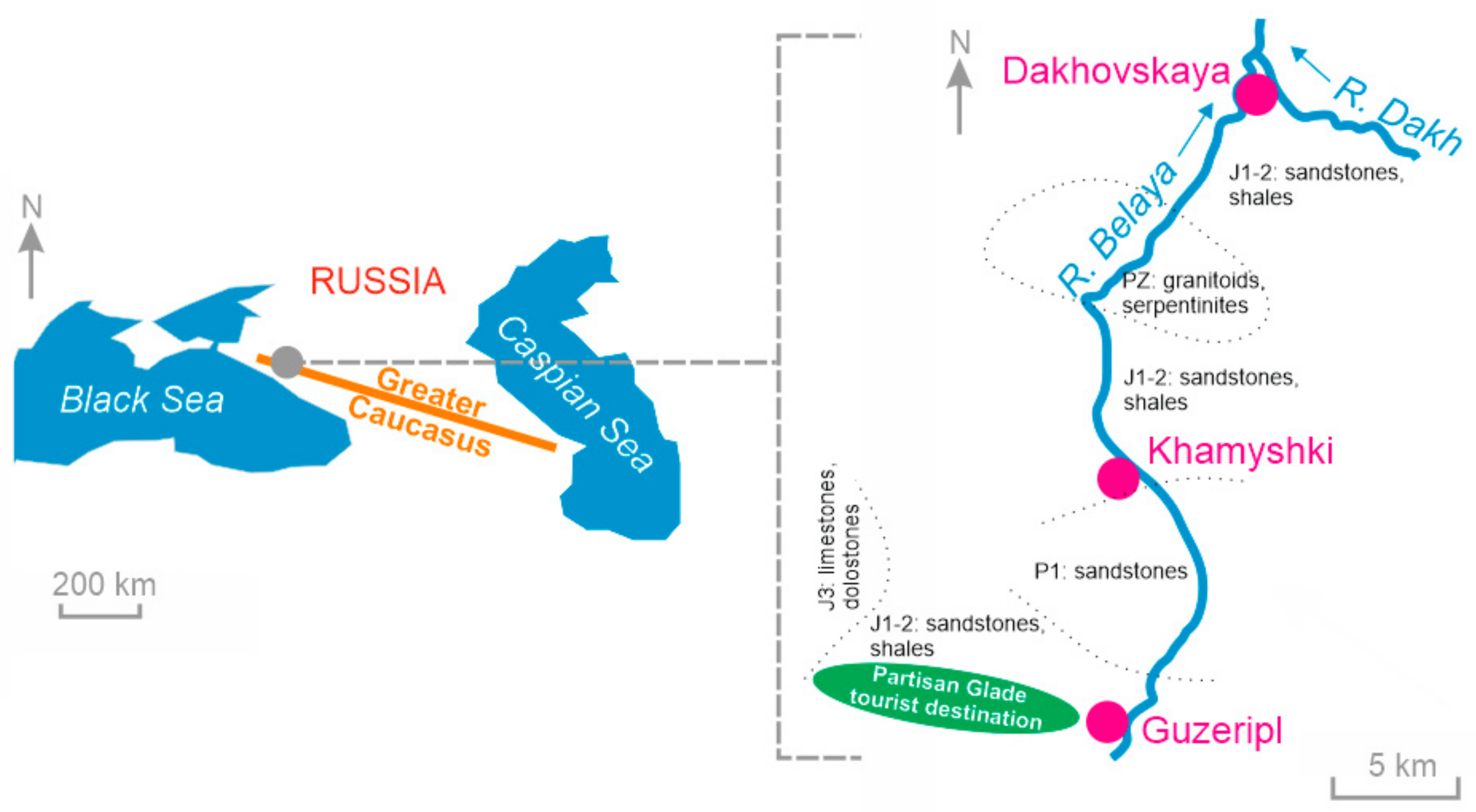

The Western Caucasus in the southwestern part of Russia hosts several nationally- and regionally-important tourist destinations boasting both scenic beauty and natural heritage. One of them is the Partisan Glade located in the mountainous part of Adygeya (Figure 1). This destination is ideal for the development of geotourism activities because of a spectrum of unique geological and geomorphological phenomena represented there (Lower–Middle Jurassic black shales, Upper Jurassic carbonate platform deposits, cuesta-type landforms, well-visible fault surfaces, strong rock folding, numerous springs and waterfalls, etc.). Generally, the study area possesses significant geological and geomorphological heritage (unique phenomena are listed above), and it can be attributed to a big geosite, the exact delineation and description of which is beyond the purposes of the present study. However, the Partisan Glade tourist destination seems to be geosite-based. Big stones occur there either individually or in groups on mountain slopes covered by dense forest. These sedimentary clasts are very typical for the entire mountainous part of Adygeya [12] and result from slope collapse and cliff retreat, i.e., these clasts are colluvial in origin [13]. The objective of the present paper is to provide the first report of the aesthetic properties of colluvial blocks occurring in the Partisan Glade tourist destination. It is based on new field investigations and does not repeat the previous findings [12,13]. Aesthetic properties of the studiedbig stones are ‘projected’ on the local scenic beauty.

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the study area. Boundaries (dotted grey lines) delineating the main rock packages are shown very approximately.

2. Geographical and Geological Setting

The Partisan Glade tourist destination (44°05'N, 40°10'E) is located to the west of the small town of Guzeripl in the Western Caucasus (Figure 1). The landscape is dominated by mountain ranges (Figure 2) and valleys of small rivers and streams; the elevation ranges between 600 m and 2000 m. The ranges are either symmetrical, with more or less smoothed slopes (e.g., the Inzhenernyy Range and the Skazhennyy Range), or they are asymmetrical, cuesta-type ranges, with one very gentle slope and the other a steep, cliffed slope (e.g., the Kamennoe More Range) [13]. The main rivers are the Zhelobnaya River and its right tributary, namely the Armyanka River. The climate is temperate. Summers are hot with temperaturesup to +30 °C and significant rainfall, winters are cold with temperatures as low as −10° and significant snowfall. The mountain slopes are covered by coniferous and mixed (coniferous–deciduous) forests. The human activities include local wood production, road maintenance, and tourism, but the visible human impact is minimal.

Figure 2.

A typical landscape view of the study area.

Geologically, this tourist destination is fully dominated by the folded and faulted Lower–Middle Jurassic black shales with rare and thin sandstone and siltstone interbeds [13,14,15]. Their lengthy outcrops stretch for many kilometers along the road. The Upper Jurassic reefal limestones and dolostones are exposed in the uppermost parts of the slopes [13,14,15]. These rocks were formed in a back-arc basin that persisted from the mid-Mesozoic to the mid-Cenozoic [16], and the modern mountains are the direct outcome of the Late Cenozoic (Alpine) orogeny [17,18,19] that have resulted from a plate collision [20].

The central element of the Partisan Glade tourist destination is the ~20 km-long road from Guzeripl to the toe of the Lagonaki Highland. The destination includes two major attractions, namely the Maple Glade with trails for hiking and skiing infrastructure and the Partisan Glade with infrastructure for nature-based recreation, including lodges and an artificial lake. Additionally, numerous points for long-distance panoramic views make this destination impressive. These points are located along the above-mentioned road. The tourist flow to the entire Adygeyaincreases by 2–5% annually, and it reached 465,000 tourists in 2019 [21]. A significant number of these tourists visit the mountainous part of this region, where the study area is located. The destination itself attracts crowds of tourists (up to one to two hundred per day) annually offering opportunities for nature-based recreation, hiking, and skiing, as well as for eco- and geotourism (peaks of tourist arrivals occur in July–August, the New Year holidays, and the early May holidays). Geotourism still occurs on an occasional basis (first of all due to the limited demand, although academic geotourists visit this destination). The natural wilderness remains almost undisturbed by the humans, and the outstanding scenic beauty of the entire destination contributes significantly to its attractiveness;as a result, photo making from the road is among the main tourist activities.

3. Methodology

Fieldworks organized in 2018 and 2019 have permitted to undertake an inventory of big stones that occur near the road stretching across the Partisan Glade tourist destination. The space along the entire road was visually checked in order to find big stones. A total of eight representative examples have been chosen for the purposes of this study. The apparently small number of these examples does not matter in this case because of two reasons. First, this study aims at the examination of the aesthetic properties of landscapes with big stones, not big stones themselves (i.e., if these stones are not numerous, this reflects the given landscape). Second, all principal occurrences of big stones are covered by this study. Each of the registered stones was measured. The maximum size, elongation and orientation, and general shape were documented, as well as their lithological composition. The stones are termed according to the size classification by Bruno andRuban [22] (Table 1). Some recommendations on descriptions of clast shape given by BlottandPye [23] are taken into account. The colluvial (related to slope destruction) nature of all studied objects was confirmed in the course of their field examination.

Table 1.

Size classification of colluvial blocks (after [22]).

The scenic beauty is often evaluated via its perception by the people [24,25] or by a researcher's scoring [26]. However, another objective and relatively simple approach has become possible thanks to the accumulated knowledge of tourist preferences [5]. The aesthetic value of the studied colluvial blocks is established qualitatively as follows. Kirillova et al. [5] outlined several main criteria of tourist judgments of beauty (scale, time, condition, sound, balance, diversity, novelty, shape, and uniqueness). These criteria refer to objective characteristics of tourist attractions, and, thus, these can be used as scenic beauty parameters (similarly, sub-criteria can be used as sub-parameters). Landscapes can be examined by these parameters. Undoubtedly, only some of them matter in each given case because a given landscape can possess only some characteristics from those relevant to beauty judgments. The physical properties of the analyzed landscape permit to establish its meaningful parameters. This permits to understand how this landscape “appeals” to the common tourist perception of beauty. However, whether this perception will be positive, negative, or neutral depends on interpretation schemes used by society, groups, and individuals. Taking into account the physical properties of the colluvial blocks studied in the Partisan Glade tourist destination, it is possible to establish which beauty parameters of the local landscape these blocks influence on and how.

4. Results

The studied large clasts range in size from 1.1 m to 5.5 m (Table 2), and, therefore, these are true blocks, according to the classification of Bruno and Ruban [22] (Table 1). These colluvial blocks differ in size, and, thus, represent all three grades of the block class (Table 2). It should be noted that the very possibility to find these grades proves the validity of the proposed classification [22]. The shape of the blocks is chiefly irregular, although patterns of sphericity are seen in some cases; the angularity is strong, but pre-detachment, karst-related surface smoothing and angle rounding are evident in many cases (Figure 3). The blocks are more or less elongated, but these differ by orientation (Table 2, Figure 3). Most probably, this difference results from the approaches of how these blocks 1) moved (fell) downslope immediately after detachment from the cliff of cuesta-type ranges (in the case of blocks of the Upper Jurassic carbonates) and the exposures of the Lower Jurassic sandstones and 2) slid later by gentle slopes where “soft” Jurassic shales are exposed.

Table 2.

Geological parameters of the studied colluvial blocks.

Figure 3.

Blocks of the Partisan Glade tourist destination considered in the present study (the numbers correspond to block IDs in Table 2).

Four blocks are composed ofthe Upper Jurassic carbonates, and one block has a strikingly different composition, i.e., the Lower Jurassic sandstone (Table 2). This means that the general process of valley growth and slope retreat on the study area is more important for block formation than the type of hard rocks eroded in the upper part of mountain slopes. Importantly, the sandstone block demonstrates better sphericity and surface smoothing, and lesser angularity (ID 5 – Figure 3). Most probably, this reflects the different hardness of sandstones and carbonates.

Considering the aesthetic parameters of the local landscape in points where the studied blocks occur, it appears that scale, condition, balance, diversity, shape, and uniqueness of the landscape can be related to these blocks; notably, only some sub-parameters matter (Table 3). Two lines of evidence should be taken into account. First, the presence of colluvial blocks affects the local landscape, especially via increasing its colour contrast and adding big-sized elements (Table 3). Second, individual blocks and their groups are distributed within the entire destination, which means multiple influences on the landscape aesthetic properties. Therefore, the importance of the studied colluvial blocks to the scenic beauty is significant, as well as their aesthetic value.

Table 3.

Determinants of the aesthetic value of the studied colluvial blocks.

5. Discussion and Conclusion

A positive, neutral, or negative perception of the natural landscape of the Partisan Glade destination by tourists, i.e., their satisfaction, depends on their own preferences. Each scenic beauty parameter has a different meaning for tourists [5]. It is possible to hypothesize that the block influence on such local landscape parameters of beauty as scale, diversity, and uniqueness will be perceived positively because tourists intend to ‘feel’ the impressive wilderness of nature. In contrast, the influence on the condition parameter will result in negative emotions because of evident safety concerns. Finally, the influence on balance and shape can be insignificant to the satisfaction of tourists because many of the latter are unexperienced to pay attention to landscape details. These hypotheses require further testing with psychological experiments—an important addition would besensible. The studied blocks are small-scale landscape elements, especially because long-distance panoramic views to the mountains of the Western Caucasus dominate the route across the Partisan Glade destination. However, their colour and size make them well-visible. As the opportunity to concentrate attention on such minor, but well-distinguished features increases positive landscape perception [6], the physical characteristics of the blocks make them local attractors to the scenic beauty.

Two conceptual ideas are relevant to the aesthetic evaluation of the colluvial blocks, namely 1) ecosystem services and 2) ecosystem intrinsic value. The idea of ecosystem services has been developed for two decades, and it relates to the functions of natural systems (i.e., landscapes) to society needs [27,28,29]. Four categories of ecosystem services are distinguished, namely supporting, provisioning, regulating, and cultural; the latter includes aesthetic and recreation services [29]. If so, the colluvialmegaclasts of the Partisan Glade tourist destination generate some economic benefits in a complex way. These contribute to the aesthetic properties of the local landscape, and such a contribution is vital for tourism, i.e., recreational service. In their “fresh” review, Costanza et al. [28] showed that ecosystem services are closely related to natural capital; particularly, cultural services permit to use this capital via experience. The colluvial blocks are minor components of the local natural system, and, thus, the local natural capital. Their influence on landscape aesthetics seems to be the only approach to how these are involved in natural capital use. The idea of ecosystem intrinsic value opposes the former idea of ecosystem services somewhat. This value is restricted to nature, i.e., without consideration of society’s needs [30,31]. It can be established via measurements of energy, matter, and information in ecosystems. As the colluvial blocks contribute to the landscape aesthetics, these possess some information. It is known that calculations of the “cost” of ecosystems and their elements bring different results, and services value is much lower thanintrinsic value [27,28,29,30,31]. An important task for future studies is an economic evaluation of the local landscapes of the destination and, particularly, colluvial blocks. The outcome of the present analysis is clear evidence of the ultimate importance of aesthetic reasons for the economic importance of the blocks.

A comparative analysis of the aesthetic value of landscapes with blocks seems to be a promising topic for further investigations. For instance, some representative examples of natural landscapes with big stones can be found in the desert areas of Egypt and, particularly, in the Bahariya and Faiyum oases [32,33,34,35]. Megaclasts there are more numerous (dominating the local landscape), lying on a flat, non-vegetated surface, and spherical and well-rounded. These leave an impression of “melon fields”, and such an “unnatural” occurrence determines their aesthetic value that differs essentially from what is reported from the Partisan Glade tourist destination.

Conclusively, the present study implies colluvial blocks occurring along the road stretching through the Partisan Glade tourist destination are of aesthetic value because of their influence on the local scenic beauty. This finding is of double practical importance. First, it permits to understand better the natural attractors of the destination. Second, it means that the colluvial blocks contribute tothe local landscape peculiarity and identity. This is an argument against block removal or breaking in the course of road maintenance and other infrastructural developments.

Author Contributions

Methodology, D.A.R., E.S.S., and N.N.Y.; investigation, D.A.R., V.A.E., and N.N.Y.; writing, D.A.R. and E.S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully thank the journal editors and the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions, as well as N.V. Ruban (Russia) for field assistance and L.P. Zhang (China) for discussion of ecosystem values.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bruwer, J.; Rueger-Muck, E. Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view. Tour. Hosp. Res. 2019, 19, 488–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooser, A.; Anfuso, G.; Mestanza, C.; Williams, A.T. Management implications for the most attractive scenic sites along the Andalusia coast (SW Spain). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirpke, U.; Tappeiner, G.; Tasser, E.; Tappeiner, U. Using conjoint analysis to gain deeper insights into aesthetic landscape preferences. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 96, 202–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowling, R.; Newsome, D. (Eds.) Handbook of Geotourism; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kirillova, K.; Fu, X.; Lehto, X.; Cai, L. What makes a destination beautiful? Dimensions of tourist aesthetic judgment. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 282–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. Consensus in factors affecting landscape preference: A case study based on a cross-cultural comparison. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 252, 109622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, J.E. Geoheritage, geotourism and the cultural landscape: Enhancing the visitor experience and promoting geoconservation. Geosciences 2018, 8, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, M. Geodiversity. Valuing and Conserving Abiotic Nature; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Henriques, M.H.; Brilha, J. UNESCO Global Geoparks: A strategy towards global understanding and sustainability. Episodes 2017, 40, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olafsdottir, R. Geotourism. Geosciences 2019, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynard, E.; Brilha, J. (Eds.) Geoheritage: Assessment, Protection, and Management; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lubova, K.A.; Zayats, P.P.; Ruban, D.A.; Tiess, G. Megaclasts in geoconservation: Sedimentological questions, anthropogenic influence, and geotourism potential. Geologos 2013, 19, 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruban, D.A. Unusual Isolated Large Clasts from the Periphery of the Lagonaki Highland, Western Caucasus: New Evidence of Classification and Origin. Geosciences 2018, 8, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovoj, S.P. Lagonakskoe Nagor’e; Krasnodarskoe Knizhnoe Izdatel’stvo: Krasnodar, Russia, 1984. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtsev, K.O.; Agaev, V.B.; Azarian, N.R.; Babaev, R.G.; Beznosov, N.V.; Hassanov, N.A.; Zesashvili, V.I.; Lomize, M.G.; Paitschadze, T.A.; Panov, D.I.; et al. Yura Kavkaza; Nauka: St. Petersburg, Russia, 1992. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Adamia, S.; Alania, V.; Chabukiani, A.; Kutelia, Z.; Sadradze, N. Great Caucasus (Cavcasioni): A Long-lived North-Tethyan Back-Arc Basin. Turk. J. Earth Sci. 2011, 20, 611–628. [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov, V.G. Collision and mountain building. Geotectonics 2016, 50, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trikhunkov, Y.I.; Bachmanov, D.M.; Gaidalenok, O.V.; Marinin, A.V.; Sokolov, S.A. Recent Mountain Building at the Junction Zone of the Northwestern Caucasus and Intermediate Kerch–Taman Region, Russia. Geotectonics 2019, 53, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, A. Cenozoic tectonic evolution of Asia: A preliminary synthesis. Tectonophysics 2010, 488, 293–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, Y. Caucasus collisional history: Review of data from East Anatolia to West Iran. Gondwana Res. 2017, 49, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuga.ru [News Portal]. Available online: https://www.yuga.ru/news/447925/ (accessed on 27 January 2020).

- Bruno, D.E.; Ruban, D.A. Something more than boulders: A geological comment on the nomenclature of megaclasts on extraterrestrial bodies. Planet. Space Sci. 2017, 135, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blott, S.J.; Pye, K. Particle shape: A review and new methods of characterization and classification. Sedimentology 2008, 55, 31–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.-H.; Han, K.-T. Assessment of aesthetic quality on soil and water conservation engineering using the scenic beauty estimation method. Water 2018, 10, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Garcia, C.; Burriel, M.; Alcazar, J. Social valuation of scenic beauty in Catalonian beech forests. Investig. Agrar. Sist. Y Recur. For. 2011, 20, 195–208. [Google Scholar]

- Warowna, J.; Zglobicki, W.; Kolodynska-Gawrysiak, R.; Gajek, G.; Gawrysiak, L.; Telecka, M. Geotourist values of loess geoheritage within the planned Geopark Malopolska Vistula River Gap, E Poland. Quat. Int. 2016, 399, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; d’Arge, R.; de Groot, R.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M.; Hannon, B.; Limburg, K.; Naeem, S.; Oneill, R.V.; Paruelo, J.; et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 1997, 387, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; de Groot, R.; Braat, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Fioramonti, L.; Sutton, P.; Farber, S.; Grasso, M. Twenty years of ecosystem services: How far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 2017, 28, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.P.; Xu, H.N.; Sheng, H.X.; Chen, W.Q.; Fang, Q.H. Concept and Evaluation of Ecosystem Intrinsic Value. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. B 2015, 5, 401–409. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, H.-X.; Xu, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, W. Ecosystem intrinsic value and its application in decision-making for sustainable development. J. Nat. Conserv. 2019, 49, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhwadi, Z.; Sallem, E.S. Spheroidal “Cannonballs” calcite-cemented concretions from the Faiyum and Bahariya depressions, Egypt: Evidence of differential erosion by sand storms. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 108, 2291–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plyusnina, E.E.; Sallam, E.S.; Ruban, D.A. Geological heritage of the Bahariya and Farafra oases, the central Western Desert, Egypt. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2016, 116, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, E.S.; Ruban, D.A. Ancient tufa and semi-detached megaclasts from Egypt: Evidence for sedimentary rock classification development. Int. J. Earth Sci. 2019, 108, 1615–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, E.S.; Fathy, E.E.; Ruban, D.A.; Ponedelnik, A.A.; Yashalova, N.N. Geological heritage diversity in the Faiyum Oasis (Egypt): A comprehensive assessment. J. Afr. Earth Sci. 2018, 140, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).