A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

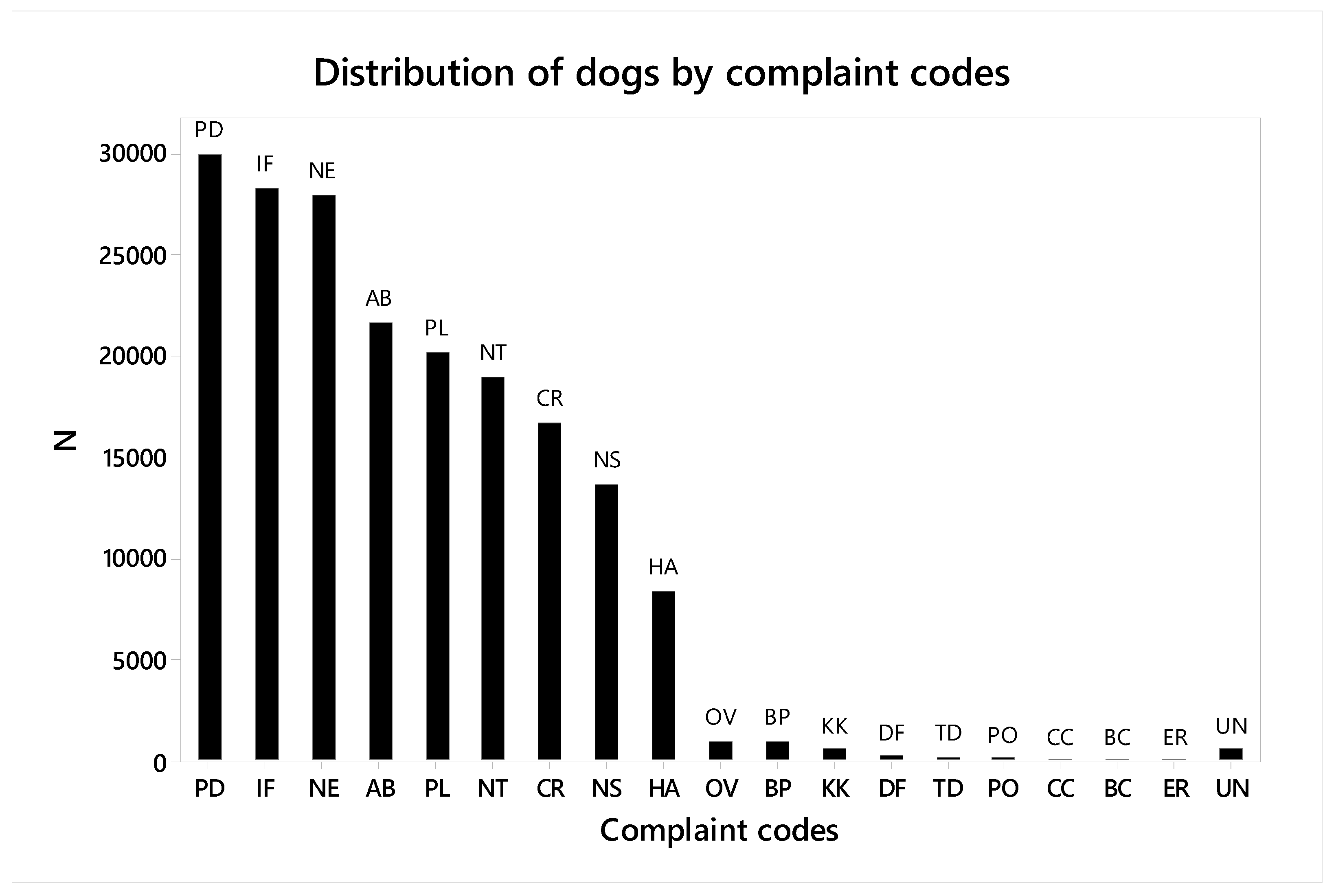

3.1. Complaint Codes and Dogs’ Ages

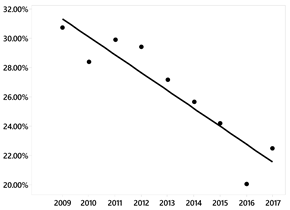

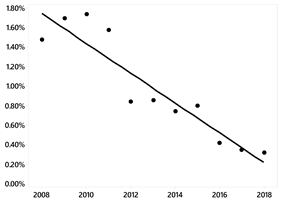

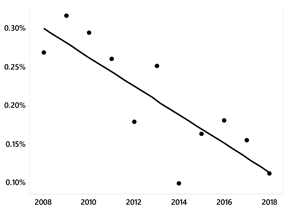

3.2. Trends of Complaint Types

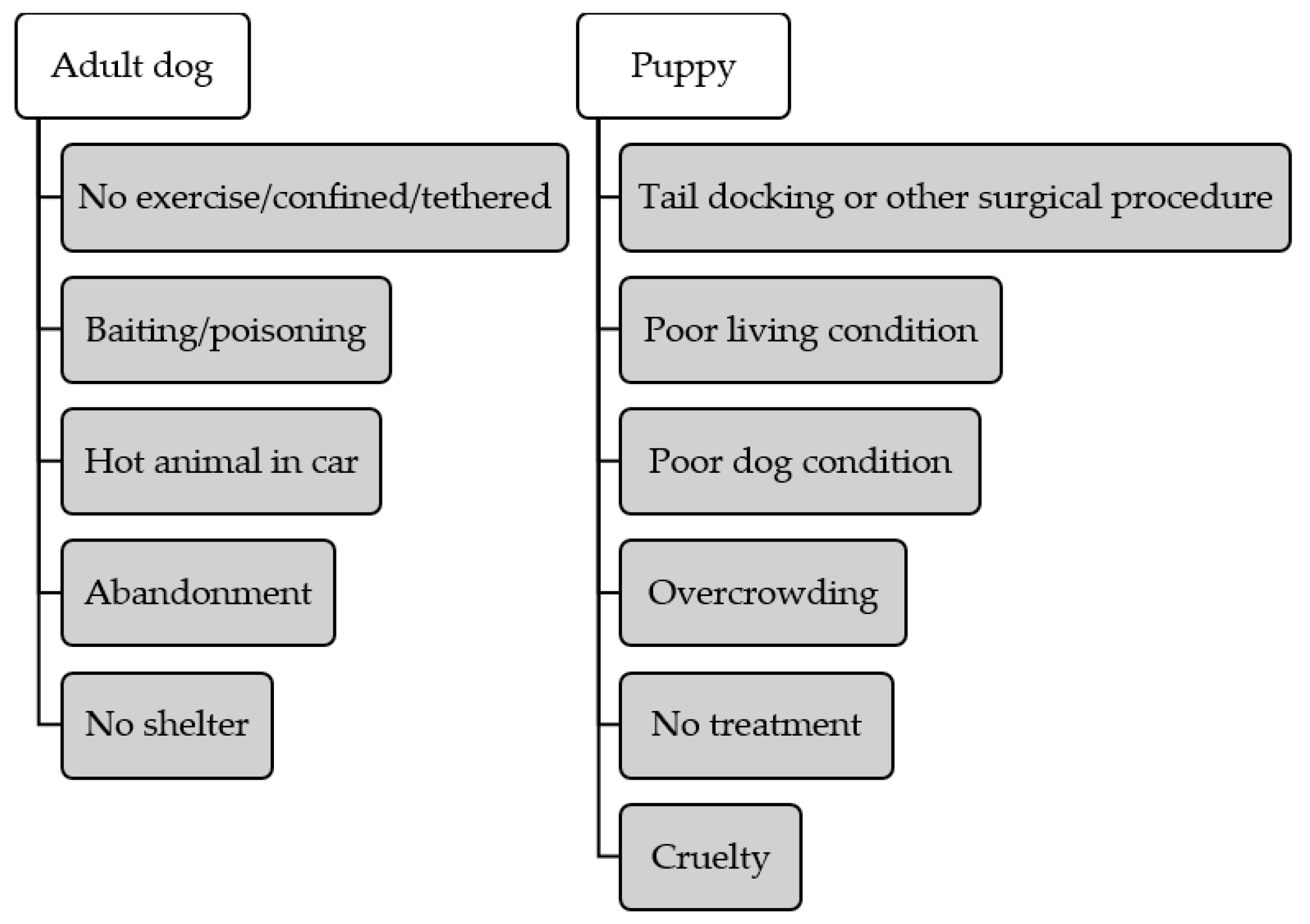

3.3. Risk Factors for Different Complaint Codes

4. Discussion

4.1. Complaint Codes

4.2. Trends Over Time

4.3. Adult Dogs and Puppies

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Complaint Code | Description |

|---|---|

| Abandonment | An animal was abandoned/left by the owner either at their abode or somewhere else such as in the bush. |

| Baiting/Poisoning | An animal was poisoned or planned to be poisoned. |

| Causing captive animal to be injured/killed by dog | A person let a captive animal be injured/killed by a dog. |

| Cruelty | A person was reported to have abused an animal. |

| Dog fighting or other prohibited offence | A person was reported for allowing dogs to fight or conducting other specifically prohibited acts. |

| Emergency relief | Emergency relief is required for an animal left unattended because its owner experienced an emergency (e.g., flood or being hit by a car). |

| Hot animal in car | An animal was left unattended in a car during hot weather. |

| Insufficient food and/or water | An animal has insufficient food and/or water. |

| Keeping or using animal for blooding/coursing a dog | A person used a live bait for blooding/coursing a dog. |

| Knowingly allowing an animal to kill/injure another | A person allowed one animal to kill/injuring another one, and did nothing to stop them. |

| No exercise/confined/tethered | An animal is confined or tethered and not given a suitable amount of exercise. |

| No shelter | An animal is not provided with suitable shelter provisions. |

| No treatment | An animal did not receive appropriate medical treatment when needed. |

| Overcrowding | The number of animals is too high for the living space provided. |

| Poor dog condition | The general condition of an animal is poor. (e.g., messy/matted coat, pussy eyes, etc.) |

| Poor living condition | The living environment of the animal is poor. |

| Prohibition order breached | An owner violated a prohibition order (a). |

| Tail docking or other surgical procedure | Tail docking or other surgical procedure (e.g., declaw removal, etc.) was conducted on an animal. |

| Unknown | Unknown |

| Complaint Code | Prevalence % (N) January–June, 2009 | Prevalence % (N) July–December, 2009 | p-Value | Prevalence % (N) January–June, 2017 | Prevalence % (N) July–December, 2017 | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Treatment | 13.2% (500/3787) | 13.9% (576/4134) | 0.343 | 18.9% (1203/6369) | 17.1% (1135/6632) | 0.008 |

| Abandonment | 13.8% (523/3787) | 14.5% (601/4134) | 0.354 | 20.4% (1298/6369) | 19.4% (1288/6632) | 0.171 |

| Cruelty | 15.2% (575/3787) | 16.7% (692/4134) | 0.059 | 14.6% (933/6369) | 14.6% (970/6632) | 0.970 |

| Insufficient food and/or water | 26.9% (1017/3787) | 25.9% (1073/4134) | 0.364 | 24.4% (1551/6369) | 24.1% (1599/6632) | 0.748 |

| No shelter | 11.3% (428/3787) | 12.4% (513/4134) | 0.128 | 13.2% (843/6369) | 14.3% (948/6632) | 0.080 |

| No exercise/confined/tethered | 31.8% (1206/3787) | 29.7% (1226/4134) | 0.035 | 21.4% (1366/6369) | 23.4% (1554/6632) | 0.007 |

| Hot Animal in Car | 4.7% (177/3787) | 6.2% (256/4134) | 0.003 | 8.3% (530/6369) | 9.5% (630/6632) | 0.018 |

| Poor living conditions | 13.8% (523/3787) | 15.5% (640/4134) | 0.036 | 23.0% (1462/6369) | 22.5% (1490/6632) | 0.507 |

| Baiting/poisoning | 0.7% (27/3787) | 1.2% (51/4134) | 0.018 | 0.8% (52/6369) | 1.1% (73/6632) | 0.097 |

| Poor dog condition | 24.1% (914/3787) | 23.1% (956/4134) | 0.291 | 31.9% (2033/6369) | 29.4% (1948/6632) | 0.002 |

| Overcrowding | 1.6% (61/3787) | 1.8% (73/4134) | 0.593 | 0.4% (25/6369) | 0.3% (20/6632) | 0.377 |

| Knowingly allowing an animal to kill/injure another | 0.5% (20/3787) | 0.6% (23/4134) | 0.864 | 0.3% (20/6369) | 0.2% (14/6632) | 0.250 |

| Tail docking or other surgical procedure | 0.3% (13/3787) | 0.3% (12/4134) | 0.675 | 0.1% (9/6369) | 0.2% (11/6632) | 0.721 |

| Dog fighting or other prohibited offence | 0.2% (6/3787) | 0.2% (7/4134) | 0.905 | 0.2% (10/6369) | 0.3% (19/6632) | 0.118 |

| Prohibition order breached | 0% (0/3787) | 0% (0/4134) | -- | 0.2% (15/6369) | 0.2% (10/6632) | 0.270 |

References

- Queensland Government--Department of Agriculture and Fisheries. Animal Care and Protection Act 2001. Available online: https://www.legislation.qld.gov.au/view/pdf/inforce/current/act-2001-064 (accessed on 22 April 2019).

- Mogbo, T.C.; Oduah, F.N.; Okeke, J.J.; Ufele, A.N.; Nwankwo, O.D. Animal cruelty: A review. J. Nat. Sci. Res. 2013, 3, 94–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ascione, F.R. Children who are cruel to animals: A review of research and implications for developmental psychopathology. Anthrozoös 1993, 6, 226–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, R.; Arkow, P. Animal abuse and interpersonal violence: The cruelty connection and its implications for veterinary pathology. Vet. Pathol. 2016, 53, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Queensland (RSPCA Qld). Annual Report 2011/2012. Available online: https://www.rspcaqld.org.au/who-we-are/annual-report (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- The Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Queensland (RSPCA Qld). Annual Report 2017–2018. Available online: https://www.rspcaqld.org.au/who-we-are/annual-report (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Tallichet, S.E.; Hensley, C. Rural and urban differences in the commission of animal cruelty. Int. J. Offender Ther. 2005, 49, 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weng, H.Y.; Kass, P.H.; Hart, L.A.; Chomel, B.B. Risk factors for unsuccessful dog ownership: An epidemiologic study in Taiwan. Prev. Vet. Med. 2006, 77, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- New, J.C.J.; Salman, M.D.; King, M.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H.; Hutchison, J.M. Characteristics of shelter-relinquished animals and their owners compared with animals and their owners in U.S. pet-owning households. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2000, 3, 179–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westgarth, C.; Christian, H.E.; Christley, R.M. Factors associated with daily walking of dogs. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.M.; Kim, S.A.; Lee, S.M.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, B.J.; Shin, N.S. Canine behavioral problems and their effect on relinquishment of the Jindo dog. J. Vet. Sci. 2010, 11, 345–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, J.Y.; Bain, M.J. Owner attachment and problem behaviors related to relinquishment and training techniques of dogs. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2013, 16, 168–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickup, E.; German, A.J.; Blackwell, E.; Evans, M.; Westgarth, C. Variation in activity levels amongst dogs of different breeds: Results of a large online survey of dog owners from the UK. J. Nutr. Sci. 2017, 6, e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, C.; Rhodes, R.E. Sizing up physical activity: The relationships between dog characteristics, dog owners’ motivations, and dog walking. Psychol. Sp. Exerc. 2016, 24, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newberry, M. Associations between different motivations for animal cruelty, methods of animal cruelty and facets of impulsivity. Psychol. Crime Law 2018, 24, 500–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, L.A.; Weng, H.Y. Impact of the economic recession on companion animal relinquishment, adoption, and euthanasia: A Chicago animal shelter’s experience. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2012, 15, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, E.D.; Scotto, J.; Slater, M.; Weiss, E. Risk factors for dog relinquishment to a Los Angeles municipal animal shelter. Animals 2015, 5, 1311–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperbauer, T.J. Animals and the expanding moral circle. In Subhuman: The Moral Psychology of Human Attitudes to Animals; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 152–158. ISBN 978-019-069-581-1. [Google Scholar]

- Haidt, J.; Koller, S.H.; Dias, M.G. Affect, culture, and morality, or is it wrong to eat your dog? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 65, 613–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwan, A.; Skandakumar, K. The welfare of greyhounds in Australian racing: Has the industry run its course? Aust. Anim. Prot. Law J. 2011, 6, 52–74. [Google Scholar]

- Kalof, L.; Taylor, C. The discourse of dog fighting. Humanit. Soc. 2007, 31, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burley, S. My dog’s the champ: An analysis of young people in urban settings and fighting dog breeds. Anthropol. Matter. J. 2008, 10, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, F.; French, L. Making the links: Child abuse, animal cruelty and domestic violence. Child Abuse Rev. 2004, 13, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laflamme, D.P.; Abood, S.K.; Fascetti, A.J.; Fleeman, L.M.; Freeman, L.M.; Michel, K.E.; Bauer, C.; Kemp, B.L.E.; Doren, J.R.V.; Willoughby, K.N. Pet feeding practices of dog and cat owners in the United States and Australia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2008, 232, 687–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frantz, N.Z.; Yamka, R.M.; Friesen, K.G. The effect of dietary protein on body composition and renal function in geriatric dogs. Intern. J. Appl. Res. Vet. Med. 2007, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, D.A. Nutritional management of chronic renal disease in dogs and cats. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. Pract. 2006, 36, 1377–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cutt, H.; Corti, B.G.; Knuiman, M.; Burke, V. Dog ownership, health and physical activity: A critical review of the literature. Health Place 2007, 13, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, C.; Burton, L.; McCormack, G.R. An investigation of the association between socio-demographic factors, dog-exercise requirements, and the amount of walking dogs receive. Can. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 76, 235–240. [Google Scholar]

- The Kennel Club. Breed Information Centre. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/services/public/breed/Default.aspx (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Robertson, I.D.; Irwin, P.J.; Lymbery, A.J.; Thompson, R.C.A. The role of companion animals in the emergence of parasitic zoonoses. Int. J. Parasitiol. 2000, 30, 1369–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C.S.; Traub, R.J.; Robertson, I.D.; Devlin, G.; Rees, R.; Thompson, R.C.A. Determining the zoonotic significance of Giardia and cryptosporidium in Australian dogs and cats. Vet. Parasitol. 2008, 154, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drouot, S.; Mignon, B.; Fratti, M.; Roosje, P.; Monod, M. Pets as the main source of two zoonotic species of the Trichophyton mentagrophytes complex in Switzerland, Arthroderma vanbreuseghemii and Arthroderma benhamiae. Vet. Dermatol. 2009, 20, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henn, J.B.; Gabriel, M.W.; Kasten, R.W.; Brown, R.N.; Theis, J.H.; Foley, J.E.; Chomel, B.B. Gray foxes (Urocyon cinereoargenteus) as a potential reservoir of a Bartonella clarridgeiae-like bacterium and domestic dogs as part of a sentinel system for surveillance of zoonotic arthropod-borne pathogens in Northern California. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 2411–2418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Government Statistician’s Office. Population Growth Highlights and Trends, Queensland, 2018 Edition. Available online: http://www.qgso.qld.gov.au/products/reports/pop-growth-highlights-trends-qld/pop-growth-highlights-trends-qld-2018-edn.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2018).

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2008–2009. Available online: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/3218.0~2008-09~Main+Features~Queensland (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Animal Medicines Australia. Pet Ownership in Australia|2016. Available online: http://animalmedicinesaustralia.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/AMA_Pet-Ownership-in-Australia-2016-Report_sml.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2018).

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Community demographics and the propensity to report animal cruelty. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2006, 9, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, N.; Signal, T.D. Willingness to pay: Australian consumers and “on the farm” welfare. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2009, 12, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, K. The biopolitics of animal being and welfare: Dog control and care in the UK and India. Trans. Inst. Brit. Geogr. 2013, 38, 106–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, S.L. Animal welfare volunteers: Who are they and why do they do what they do? Anthrozoös 2010, 23, 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, J.R.; Loftus, M.M.; Pasek, J. Young and older caregivers at homeless animal and human shelters: Selfish and selfless motives in helping others. J. Soc. Distress Homel. 1999, 8, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, D.C.J. Evolution of animal-welfare education for veterinary students. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2010, 37, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenebaum, J. “I’m not an activist!”: Animal rights vs. animal welfare in the purebred dog rescue movement. Soc. Anim. 2009, 17, 289–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, C.M.; Walsh, D.-A.B.; Phillips, C.J.C. Public response to media coverage of animal cruelty. J. Agri. Environ. Ethic 2013, 26, 869–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGreevy, P.D.; Starling, M.; Branson, N.J.; Cobbc, M.L.; Calnon, D. An overview of the dog–human dyad and ethograms within it. J. Vet. Behav. 2012, 7, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiplady, C.M.; Walsh, D.B.; Phillips, C.J.C. Intimate partner violence and companion animal welfare. Aust. Vet. J. 2012, 90, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeling, C.; Kerridge, I.; Rock, M. What to think of canine obesity? Emerging challenges to our understanding of human–animal health relationships. Soc. Epistemol. 2013, 27, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Having our dogs and eating them too: Why animals are a social issue. J. Soc. Issues 2009, 65, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.A.; Bauer, J.E.; Kersey, J.H.; Buff, P.R. Awareness and evaluation of natural pet food products in the United States. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2014, 245, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.J.; Cracknell, N.; Hardiman, J.; Wright, H.; Mills, D. The welfare consequences and efficacy of training pet dogs with remote electronic training collars in comparison to reward based training. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e102722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notari, L.; Gallicchio, B. Owners’ perceptions of behavior problems and behavior therapists in Italy: A preliminary study. J. Vet. Behav. 2008, 3, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zupan, M.; Buskas, J.; Altimiras, J.; Keeling, L.J. Assessing positive emotional states in dogs using heart rate and heart rate variability. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 155, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Weiss, E.; Patronek, G.; Slater, M.; Garrison, L.; Medicus, K. Community partnering as a tool for improving live release rate in animal shelters in the United States. J. Appl. Ani. Welf. Sci. 2013, 16, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dotson, M.J.; Hyatt, E.M.; Clark, J.D. Traveling with the family dog: Targeting an emerging segment. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2011, 20, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology. Climate Outlooks—Monthly and Seasonal. Available online: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/outlooks/#/temperature/maximum/median/seasonal/0 (accessed on 7 March 2019).

- Yilmaz, O. Dog fighting in some European countries. Int. J. Livest. Res. 2016, 6, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarver, E.C. The dangerous individual(‘s) dog: Race, criminality and the ‘Pit bull’. Cult. Theory Crit. 2014, 55, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, J.; Monton, S. Preferences for infant facial features in pet dogs and cats. Ethology 2010, 117, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golle, J.; Lisibach, S.; Mast, F.W.; Lobmaier, J.S. Sweet puppies and cute babies: Perceptual adaptation to babyfacedness transfers across species. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e58248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, P.C.; Perini, E. Tail docking in dogs: A review of the issues. Aust. Vet. J. 2003, 81, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noonan, G.J.; Rand, J.S.; Blackshaw, J.K.; Priest, J. Behavioural observations of puppies undergoing tail docking. Appl. Ani. Behav. Sci. 1996, 49, 335–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murno, H.M.C.; Thrusfield, M.V. “Battered pets”: Non-accidental physical injuries found in dogs and cats. J. Small Ani. Pract. 2001, 42, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, R. Cruelty toward cats: Changing perspectives. In The State of the Animals III: 2005, 1st ed.; Salem, D.J., Rowan, A.N., Eds.; Humane Society Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; pp. 15–26. ISBN 978-097-484-005-5. [Google Scholar]

- The Kennel Club. Puppy Farming. Available online: https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/our-resources/kennel-club-campaigns/puppy-farming/ (accessed on 27 February 2019).

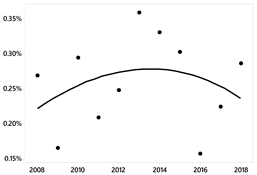

| Complaint Code | Figure | Pattern | p Value/R-Sq | ||||

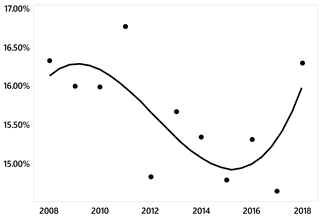

| No exercise/confined/tethered |  Y = 24.85 − 0.01221 X | Negative linear | <0.001/84.4% | ||||

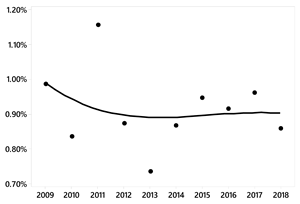

| Overcrowding |  Y = 3.081 − 0.001526 X | Negative linear | <0.001/86.5% | ||||

| Tail docking or other surgical procedure |  Y = 0.3768 − 0.000186 X | Negative linear | 0.002/69.2% | ||||

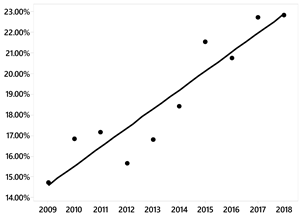

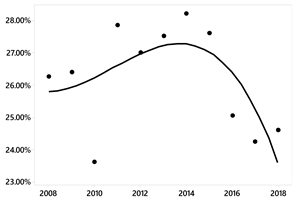

| Poor living condition |  Y = −18.34 + 0.009202 X | Positive linear | <0.001/86.7% | ||||

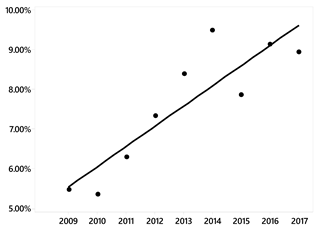

| Hot animal in car |  Y = −10.17 + 0.005089 X | Positive linear | 0.001/78.5% | ||||

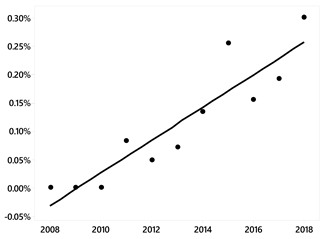

| Prohibition order breached |  Y = −0.5797 + 0.000289 X | Positive linear | <0.001/83.8% | ||||

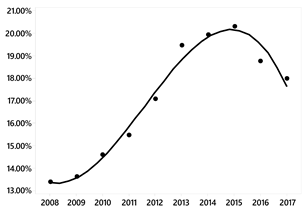

| No treatment |  Y = 3889846 − 5801 X + 2.884 X2 − 0.000478 X3 | Concave | <0.001/97.7% | ||||

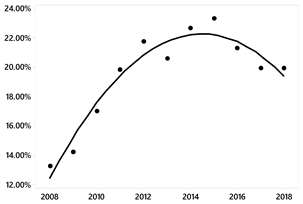

| Abandonment |  Y = −9487 + 9.419 X − 0.002338 X2 | Concave | <0.001/93.4% | ||||

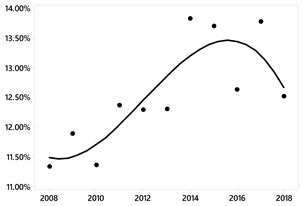

| No shelter |  Y = 886771 − 1322 X + 0.6571 X2 − 0.000109 X3 | Concave | 0.023/72.2% | ||||

| Knowingly allowing an animal to kill/injure another |  Y = −304963 + 454.2 X − 0.2255 X2 + 0.000037 X3 | Concave | 0.005/82.9% | ||||

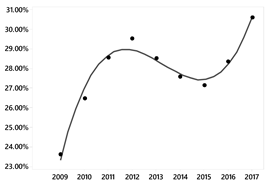

| Poor dog condition |  Y = −8311541 + 12385 X − 6.152 X2 + 0.001018 X3 | Monotonic | <0.001/97.2% | ||||

| Cruelty |  Y = −960945 + 1433 X − 0.7120 X2 + 0.000118 X3 | Irregular | 0.132/53.0% | ||||

| Insufficient food and/or water |  Y = 1258720 − 1878 X + 0.934 X2 − 0.000155 X3 | Irregular | 0.217/44.9% | ||||

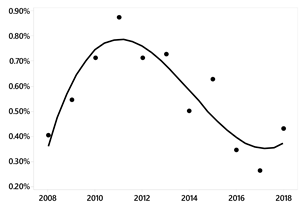

| Baiting/poisoning |  Y = 40993 − 61.0 X + 0.0303 X2 − 0.000005 X3 | Irregular | 0.917/7.6% | ||||

| Dog fighting or other prohibited offense |  Y = 1981 − 3.0 X + 0.00151 X2 − 0.000000 X3 | Irregular | 0.883/8.4% |

| Complaint Code | Puppy/Dog OR (CI) (a) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Tail docking or other surgical procedure | 9.87 (7.30, 13.34) | <0.001 |

| Overcrowding | 4.44 (3.70, 5.32) | <0.001 |

| Poor living condition | 1.45 (1.35, 1.55) | <0.001 |

| No treatment | 1.33 (1.24, 1.42) | <0.001 |

| Cruelty | 1.27 (1.18, 1.37) | 0.001 |

| Poor dog condition | 1.23 (1.16, 1.30) | <0.001 |

| No shelter | 0.91 (0.84, 1.00) | 0.037 |

| No exercise/confined/tethered | 0.64 (0.60, 0.69) | <0.001 |

| Abandonment | 0.53 (0.49, 0.58) | <0.001 |

| Baiting/poisoning | 0.42 (0.27, 0.66) | <0.001 |

| Hot animal in car | 0.41 (0.35, 0.47) | <0.001 |

| Causing captive animal to be injured/killed by dog | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Dog fighting or other prohibited offence | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Emergency relief | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Insufficient food and/or water | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Keeping or using animal for blooding/coursing a dog | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Knowingly allowing an animal to kill/injure another | -- [b] | -- [b] |

| Prohibition order breached | -- [b] | -- [b] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shih, H.Y.; Paterson, M.B.A.; Phillips, C.J.C. A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare. Animals 2019, 9, 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050282

Shih HY, Paterson MBA, Phillips CJC. A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare. Animals. 2019; 9(5):282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050282

Chicago/Turabian StyleShih, Hao Yu, Mandy B. A. Paterson, and Clive J. C. Phillips. 2019. "A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare" Animals 9, no. 5: 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050282

APA StyleShih, H. Y., Paterson, M. B. A., & Phillips, C. J. C. (2019). A Retrospective Analysis of Complaints to RSPCA Queensland, Australia, about Dog Welfare. Animals, 9(5), 282. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050282