The Emperor’s New Clothes—An Epistemological Critique of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Acupuncture

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

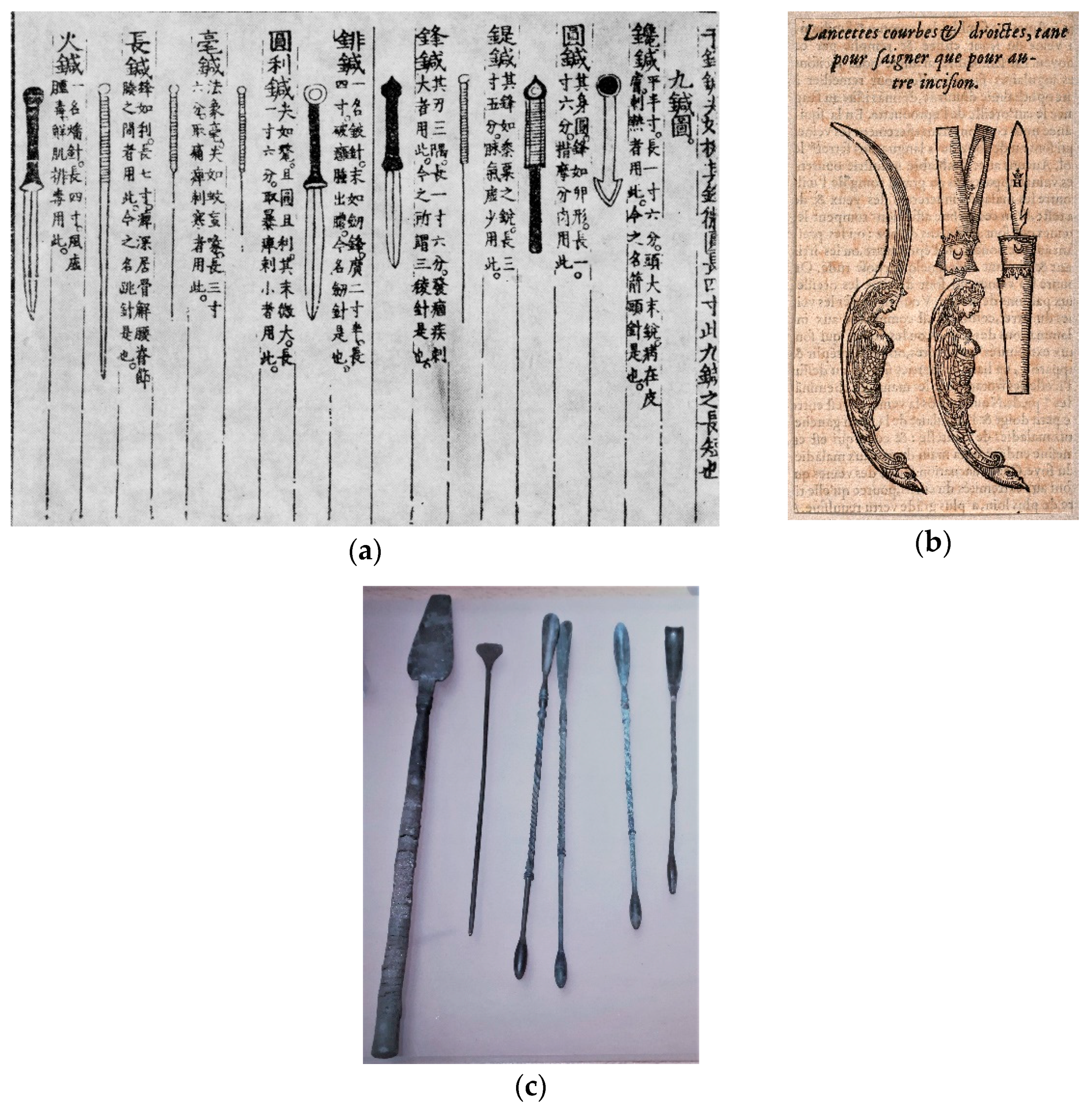

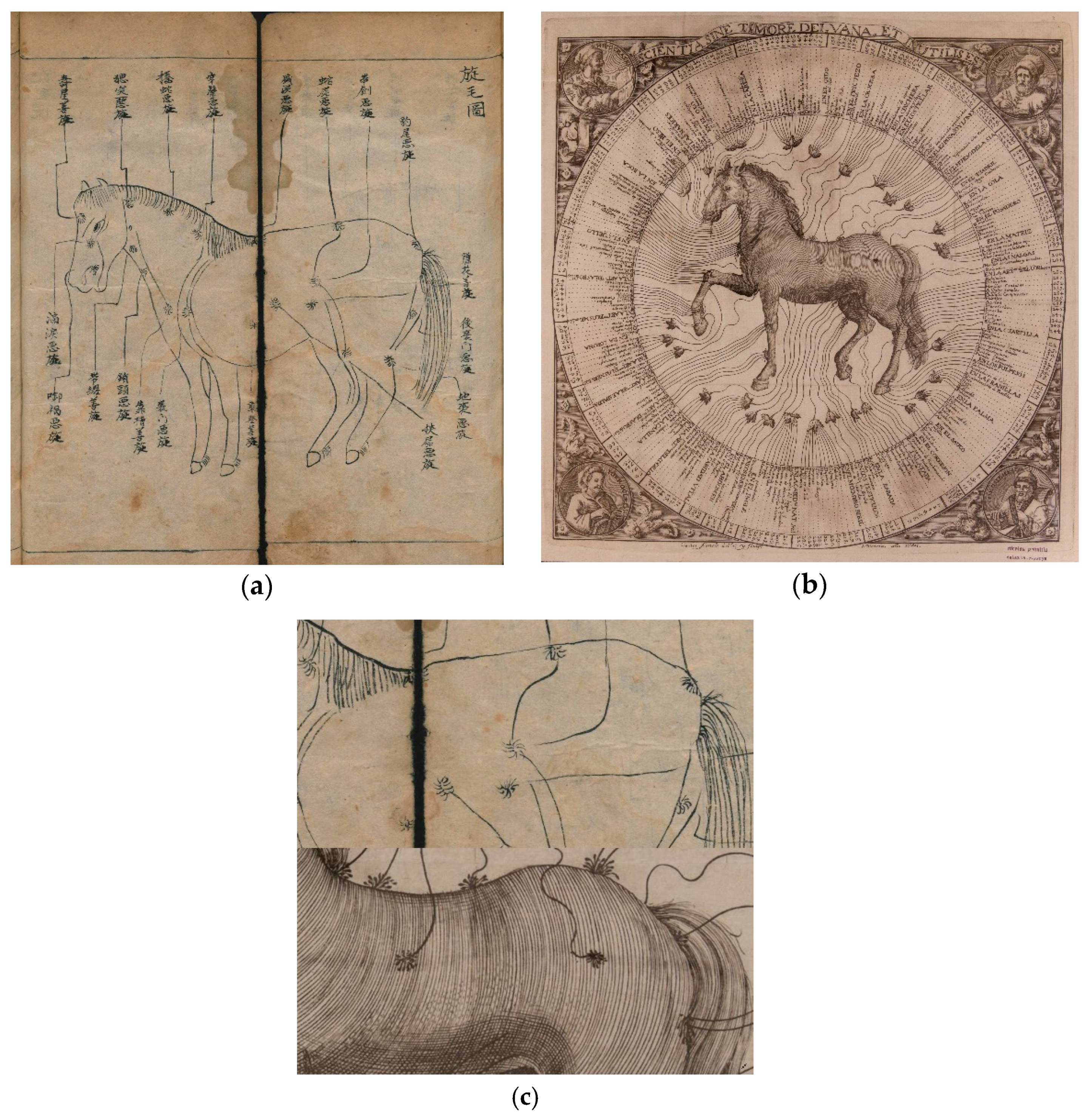

2. Conceptual and Historical Critique

AP [acupuncture]’s theory of action is grounded on TCM, on the concepts of Yin and Yang, that represent the balance, of Qi, that represents the vital energy, and on how these energies move, how they flow and distribute throughout the body through meridians that connect the various organs and regions of the body. The AP points are located in the skin and mostly in the path of the meridians and through their stimulation it is possible to alter the energy flow and interfere with the functioning of the organs. These Eastern concepts, which were developed from the observation of nature, from biological phenomena and from responses produced by organisms to environmental stimuli, support the TCM theory and are validated by the functioning of AP.”(p. 36, translation and emphasis mine) [11]

In all inflammatory disorders bleeding is of the first importance, and cannot be performed too early. (…) One copious bleeding, that is, until the pulse sinks, will frequently crush the disorder at once; (…) From one to two galleons of blood may generally be taken from a heifer or steer, or even from a milch cow.(p. 304) [12]

Bloodletting’s theory of action is grounded on humoral doctrine, on the concepts of cold/wet and hot/dry, that represent the balance, of Pneuma, that represents the vital spirit, and on how these spirits move, how they flow, and distribute throughout the body through vessels that connect the various organs and regions of the body. The bloodletting points are located in the skin and mostly in the path of the vessels and through their stimulation it is possible to alter the spirit flow and interfere with the functioning of the organs. These Western concepts, which were developed from the observation of nature, from biological phenomena and from responses produced by organisms to environmental stimuli, support the humoral doctrine theory and are validated by the functioning of bloodletting.

(A disease of) the minor-yang (vessel) causes the abdominal region to be painful as if the skin was being pricked by a pin. Initially (the patient) is not able to bend down, nor then to look up, and then he cannot twist around. Needle the minor-yang (vessel) at the end of the Ch’eng bone so that blood flows out. (…)(p. 351) [18]

Tested by them [early veterinary acupuncturists] almost immediately, it produced quite disparate results: some favorable, others null. Failures were the most numerous; what can be attributed, in part, to the inadequate application made, from the very beginning, of this means.(p. 2, translation mine) [30]

this medicine [TCVM] uses a metaphoric language to describe the pathophysiology of disease and patterns of treatment. The traditional concept surrounds qi (pronounced chee), which is usually translated as energy or life force. The qi circulates through all parts of the body via pathways called meridians. Up to 350 points along and around these meridians have increased bioactivity and are called acupuncture points.(p. 53) [31]

“once it has achieved the status of paradigm, a scientific theory is declared invalid only if an alternate candidate is available to take its place. (…) The decision to reject one paradigm is always simultaneously the decision to accept another, and the judgment leading to that decision involves the comparison of both paradigms with nature and with each other. (…) to reject one paradigm without simultaneously substituting another is to reject science itself.”(pp. 77–79) [38]

3. Scientific Critique

Needles and needle-induced changes are believed to activate the built-in survival mechanisms that normalize homeostasis and promote self-healing. In this context, acupuncture can be defined as a physiologic therapy coordinated by the brain that responds to the stimulation of manual and electrical needling of peripheral sensory nerves, in which acupuncture does not treat any particular pathologic system, but normalizes physiologic homeostasis and promotes self-healing(p. 249, emphasis mine) [66]

Placebo and placebo-induced changes are believed to activate the built-in survival mechanisms that normalize homeostasis and promote self-healing. In this context, placebo can be defined as a physiologic therapy coordinated by the brain that responds to the stimulation of [ ] sensory nerves, in which placebo does not treat any particular pathologic system, but normalizes physiologic homeostasis and promotes self-healing.

4. Final Recommendations

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gough, A.; Taylor, N. No Way to Treat a Friend: Lifting the Lid on Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine, 1st ed.; 5m Publishing: Portland, OR, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey, D.M.; Rollin, B.E. Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine Considered; Iowa State Press: Ames, IA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- The SkeptVet | A Vet Takes a Skeptical & Science-Based Look at Veterinary Medicine. Available online: http://skeptvet.com/Blog/ (accessed on 20 February 2019).

- Dunbar, K. How Scientists Think in the Real World: Implications for Science Education. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2000, 21, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartha, P. Analogy and Analogical Reasoning. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edward, N.Z., Ed.; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/reasoning-analogy/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Veith, I. The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Le Blanc, C.A. Re-Examination of the Myth of Huang-Ti. J. Chin. Relig. 1985, 13, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magner, L.N. A History of Medicine, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Unschuld, P.U. Medicine in China: A History of Ideas; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klide, A.M.; Kung, S.H. Veterinary Acupuncture, 2nd ed.; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Umarji, S. A Acupunctura e a Terapia Celular ao serviço da neurologia-o passado atual e o futuro presente. Vet. Atual. 2018, 113, 36–37. [Google Scholar]

- White, J. A Compendium of Cattle Medicine; or, Practical Observations on the Disorders of Cattle and the Other Domestic Animals, Except the Horse, 6th ed.; Longman: Brown, Green; London, UK, 1842. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, W.J. Modern Practical Farriery, a Complete System of the Veterinary Art; William Mackenzie: London, UK, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, E.N., Jr. Why Is Humoral Medicine So Popular? Soc. Sci. Med. 1987, 25, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavoussi, B. The Untold Story of Acupuncture. Focus Altern. Complement. Ther. 2009, 14, 276–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, N.H. Animal Experiments in Biomedical Research: A Historical Perspective. Animals 2013, 3, 238–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cyranoski, D. Why Chinese Medicine Is Heading for Clinics around the World. Available online: http://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06782-7 (accessed on 9 October 2018).

- Epler, D.C., Jr. Bloodletting in Early Chinese Medicine and Its Relation to the Origin of Acupuncture. Bull. Hist. Med. 1980, 54, 337–367. [Google Scholar]

- Kavoussi, B. The Acupuncture and Fasciae Fallacy. Available online: https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/acupuncture-and-fascial-planes-junk-science-and-wasteful-research/ (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Imrie, R.H.; Ramey, D.W.; Buell, P.D.; Ernst, E.; Basser, S.P. Veterinary Acupuncture and Historical Scholarship: Claims for the Antiquity of Acupuncture. Sci. Rev. Altern. Med. 2001, 5, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, M.-S.; Yang, I.S. 34 Equine Diseases in “Sin Pyeon Jip Seong Ma Ui Bang”: A Veterinary Historical Study. Wiener Tieraerztliche Monatsschrift 2008, 95, 296–302. [Google Scholar]

- Alves, E.M.O.; Tubino, P. Proibição Das Dissecções Anatômicas: Fato Ou Mito? J. Bras. Hist. Med. 2017, 17, 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, W.-W.; Chen, K.-Y.; Liu, H.; Wu, L.-S.; Lin, J.-H. Acupuncture for General Veterinary Practice. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2001, 63, 1057–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaggar, D. History and Basic Introduction to Veterinary Acupuncture. Probl. Vet. Med. 1992, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Jaggar, D.H.; Robinson, N.G. History of Veterinary Acupuncture. In Veterinary Acupuncture: Ancient Art to Modern Medicine; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2001; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ramey, D.W.; Imrie, R.H.; Buell, P.D. Veterinary Acupuncture and Traditional Chinese Medicine: Facts and Fallacies. Compend. Contin. Educ. 2001, 23, 188–193. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, S. Developments in Veterinary Acupuncture. Acupunct. Med. 2001, 19, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouley, H.; Reynal, J. Nouveau Dictionnaire Pratique de Médecine, de Chirugie et D’Hygiène Vétérinaires; Labé: Paris, France, 1856. [Google Scholar]

- Bouley jeune. No Title. Recl. Méd. Vét. 1825, 2, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Gourdon, J. De l’Acupuncture. In Éléments de Chirurgie Vétérinaire; Labé: Paris, France, 1857; Chapter IV; Volume 2, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell, S.L. Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine: The Mechanism and Management of Acupuncture for Chronic Pain. Top. Companion Anim. Med. 2010, 25, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroz-González, S.; Torres-Castillo, S.; López-Gómez, R.E.; Jiménez Estrada, I. Acupuncture Points and Their Relationship with Multireceptive Fields of Neurons. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2017, 10, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roynard, P.; Frank, L.; Xie, H.; Fowler, M. Acupuncture for Small Animal Neurologic Disorders. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 48, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, A.C.; Colbert, A.P.; Anderson, B.J.; Martinsen, Ø.G.; Hammerschlag, R.; Cina, S.; Wayne, P.M.; Langevin, H.M. Electrical Properties of Acupuncture Points and Meridians: A Systematic Review. Bioelectromagnetics 2008, 29, 245–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramey, D.W. A Review of the Evidence for the Existence of Acupuncture Points and Meridians. In Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the AAEP 2000; American Association of Equine Practitioners: San António, TX, USA, 2000; Volume 46, pp. 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Langevin, H.M.; Wayne, P.M. What Is the Point? The Problem with Acupuncture Research That No One Wants to Talk About. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, N.G. One Medicine, One Acupuncture. Animals 2012, 2, 395–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 3rd ed.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, H.; Eckermann-Ross, C. Introduction to Traditional Chinese Veterinary Medicine in Pediatric Exotic Animal Practice. Vet. Clin. Exot. Anim. Pract. 2012, 15, 311–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.-Q.; Shi, G.-X.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Liu, C.-Z.; Wang, L.-P. Acupuncture Effect and Central Autonomic Regulation. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 267959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochrane. Cochrane Reviews in Acupuncture. 2018. Available online: https://www.scienceinmedicine.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/Cochrane-acupuncture-2018.pdf (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Habacher, G.; Pittler, M.H.; Ernst, E. Effectiveness of Acupuncture in Veterinary Medicine: Systematic Review. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2006, 20, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goiz-Marquez, G.; Caballero, S.; Solis, H.; Rodriguez, C.; Sumano, H. Electroencephalographic Evaluation of Gold Wire Implants Inserted in Acupuncture Points in Dogs with Epileptic Seizures. Res. Vet. Sci. 2009, 86, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, D.; Hopper, K. Small Animal Critical Care Medicine, 2nd ed.; Saunders: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pons, A.; Canfrán, S.; Benito, J.; Cediel-Algovia, R.; de Segura, I.A.G. Effects of Dexmedetomidine Administered at Acupuncture Point GV20 Compared to Intramuscular Route in Dogs. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2017, 58, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radkey, D.I.; Writt, V.E.; Snyder, L.B.C.; Jones, B.G.; Johnson, R.A. Gastrointestinal Effects Following Acupuncture at Pericardium-6 and Stomach-36 in Healthy Dogs: A Pilot Study. J. Small Anim. Pract. 2018, 60, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joaquim, J.G.F.; Luna, S.P.L.; Brondani, J.T.; Torelli, S.R.; Rahal, S.C.; de Paula Freitas, F. Comparison of Decompressive Surgery, Electroacupuncture, and Decompressive Surgery Followed by Electroacupuncture for the Treatment of Dogs with Intervertebral Disk Disease with Long-Standing Severe Neurologic Deficits. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2010, 236, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colquhoun, D.; Novella, S.P. Acupuncture Is Theatrical Placebo. Anesth. Analg. 2013, 116, 1360–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Shao, X.; Zhou, C.; Guo, X.; Jin, L.; Lian, L.; Yu, X.; Dong, Z.; Mo, Y.; Fang, J. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Regulates Organ Blood Flow and Apoptosis during Controlled Hypotension in Dogs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, F.D. The Placebo Effect in Animals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1999, 215, 992–999. [Google Scholar]

- Muñana, K.R.; Zhang, D.; Patterson, E.E. Placebo Effect in Canine Epilepsy Trials. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 2010, 24, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conzemius, M.G.; Evans, R.B. Caregiver Placebo Effect for Dogs with Lameness from Osteoarthritis. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2012, 241, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, G.; Larsen, S.; Moe, L. Stratification, Blinding and Placebo Effect in a Randomized, Double Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial of Gold Bead Implantation in Dogs with Hip Dysplasia. Acta Vet. Scand. 2005, 46, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, G.T.; Larsen, S.; Søli, N.; Moe, L. Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Pain-Relieving Effects of the Implantation of Gold Beads into Dogs with Hip Dysplasia. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158, 722–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jæger, G.T.; Larsen, S.; Søli, N.; Moe, L. Two Years Follow-up Study of the Pain-Relieving Effect of Gold Bead Implantation in Dogs with Hip-Joint Arthritis. Acta Vet. Scand. 2007, 49, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolliger, C.; DeCamp, C.E.; Stajich, M.; Flo, G.L.; Martinez, S.A.; Bennett, R.L.; Bebchuk, T. Gait Analysis of Dogs with Hip Dysplasia Treated with Gold Bead Implantation Acupuncture. Vet. Comp. Orthop. Traumatol. 2002, 15, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hielm-Bjorkman, A.; Raekallio, M.; Kuusela, E.; Saarto, E.; Markkola, A.; Tulamo, R.-M. Double-Blind Evaluation of Implants of Gold Wire at Acupuncture Points in the Dog as a Treatment for Osteoarthritis Induced by Hip Dysplasia. Vet. Rec. 2001, 149, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lie, K.-I.; Jæger, G.; Nordstoga, K.; Moe, L. Inflammatory Response to Therapeutic Gold Bead Implantation in Canine Hip Joint Osteoarthritis. Vet. Pathol. 2010, 48, 1118–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, L.R.; Luna, S.P.L.; Matsubara, L.M.; Cápua, M.L.B.; Santos, B.P.C.R.; Mesquita, L.R.; Faria, L.G.; Agostinho, F.S.; Hielm-Björkman, A. Owner Assessment of Chronic Pain Intensity and Results of Gait Analysis of Dogs with Hip Dysplasia Treated with Acupuncture. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2016, 249, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hale, B. Letters to the Editor–Disputing Strong Claims of Acupuncture’s Effects. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 250, 271–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, B. Letters to the Editor–Questions Study of Acupuncture for Dogs with Hip Dysplasia. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2017, 250, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.P. Neonatal Resuscitation–Improving the Outcome. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Small Anim. Pract. 2014, 44, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goe, A.; Shmalberg, J.; Gatson, B.; Bartolini, P.; Curtiss, J.; Wellehan, J.F.X. Epinephrine or Gv-26 Electrical Stimulation Reduces Inhalant Anesthestic Recovery Time in Common Snapping Turtles (Chelydra Serpentina). J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2016, 47, 501–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, L.; Altman, S.; Rogers, P.A. Respiratory and Cardiac Arrest under General Anaesthesia: Treatment by Acupuncture of the Nasal Philtrum. Vet. Rec. 1979, 105, 273–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleckenstein, J.; Baeumler, P.; Gurschler, C.; Weissenbacher, T.; Annecke, T.; Geisenberger, T.; Irnich, D. Acupuncture Reduces the Time from Extubation to ‘Ready for Discharge’ from the Post Anaesthesia Care Unit: Results from the Randomised Controlled AcuARP Trial. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millis, D.; Levine, D. Canine Rehabilitation and Physical Therapy, 2nd ed.; Saunders, Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Duclow, D.F. William James, Mind-Cure, and the Religion of Healthy-Mindedness. J. Relig. Health 2002, 41, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emotions and Disease: Self-Healing, Patents, and Placebos. Available online: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/emotions/self.html (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- Wager, T.D.; Atlas, L.Y. The Neuroscience of Placebo Effects: Connecting Context, Learning and Health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, H. Glucosamine and Chondroitin: Do They Really Work?—CSI. Available online: http://www.csicop.org/specialarticles/show/glucosamine_and_chondroitin_do_they_really_work (accessed on 3 January 2019).

- Robinson, N.G. Making Sense of the Metaphor: How Acupuncture Works Neurophysiologically. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 2009, 29, 642–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, W. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Evidence for the Efficacy of Acupuncture for Musculoskeletal Conditions in Dogs. University of Guelph Guelph Atrium 2017. Available online: https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/11610 (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Declaração de Madrid Sobre Pseudoterapias e Pseudociências. Ordem dos Médicos de Portugal and Consejo General de Colegios Oficiales de Médicos de España. 18 January 2019. Available online: https://ordemdosmedicos.pt/portugal-e-espanha-assinam-declaracao-conjunta-sobre-pseudoterapias-e-pseudociencias/ (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- College Publishes Complementary Medicines Statement–Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons. Available online: https://www.rcvs.org.uk/news-and-views/news/college-publishes-complementary-medicines-statement/ (accessed on 7 November 2017).

- Comunicado OMV–Medicinas Não Convencionais. Available online: https://www.omv.pt/assets/newsletters/newsletter_2018-07-05-10-10-17.html (accessed on 25 January 2019).

- Brennan, M.; Chambers, D.; Christley, R.; Penfold, H. A Cross-Sectional Study Investigating the Prevalence of and Motivations for Using Alternative Medicines by Equine Owners on Their Animals. Equine Vet. J. 2018, 50, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Magalhães-Sant’Ana, M. The Emperor’s New Clothes—An Epistemological Critique of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Acupuncture. Animals 2019, 9, 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9040168

Magalhães-Sant’Ana M. The Emperor’s New Clothes—An Epistemological Critique of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Acupuncture. Animals. 2019; 9(4):168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9040168

Chicago/Turabian StyleMagalhães-Sant’Ana, Manuel. 2019. "The Emperor’s New Clothes—An Epistemological Critique of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Acupuncture" Animals 9, no. 4: 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9040168

APA StyleMagalhães-Sant’Ana, M. (2019). The Emperor’s New Clothes—An Epistemological Critique of Traditional Chinese Veterinary Acupuncture. Animals, 9(4), 168. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9040168