Veterinary Professionals’ Understanding of Common Feline Behavioural Problems and the Availability of “Cat Friendly” Practices in Ireland

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey Design

2.2. Vignette Development

2.3. Ethical Approval and Administration of Survey

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

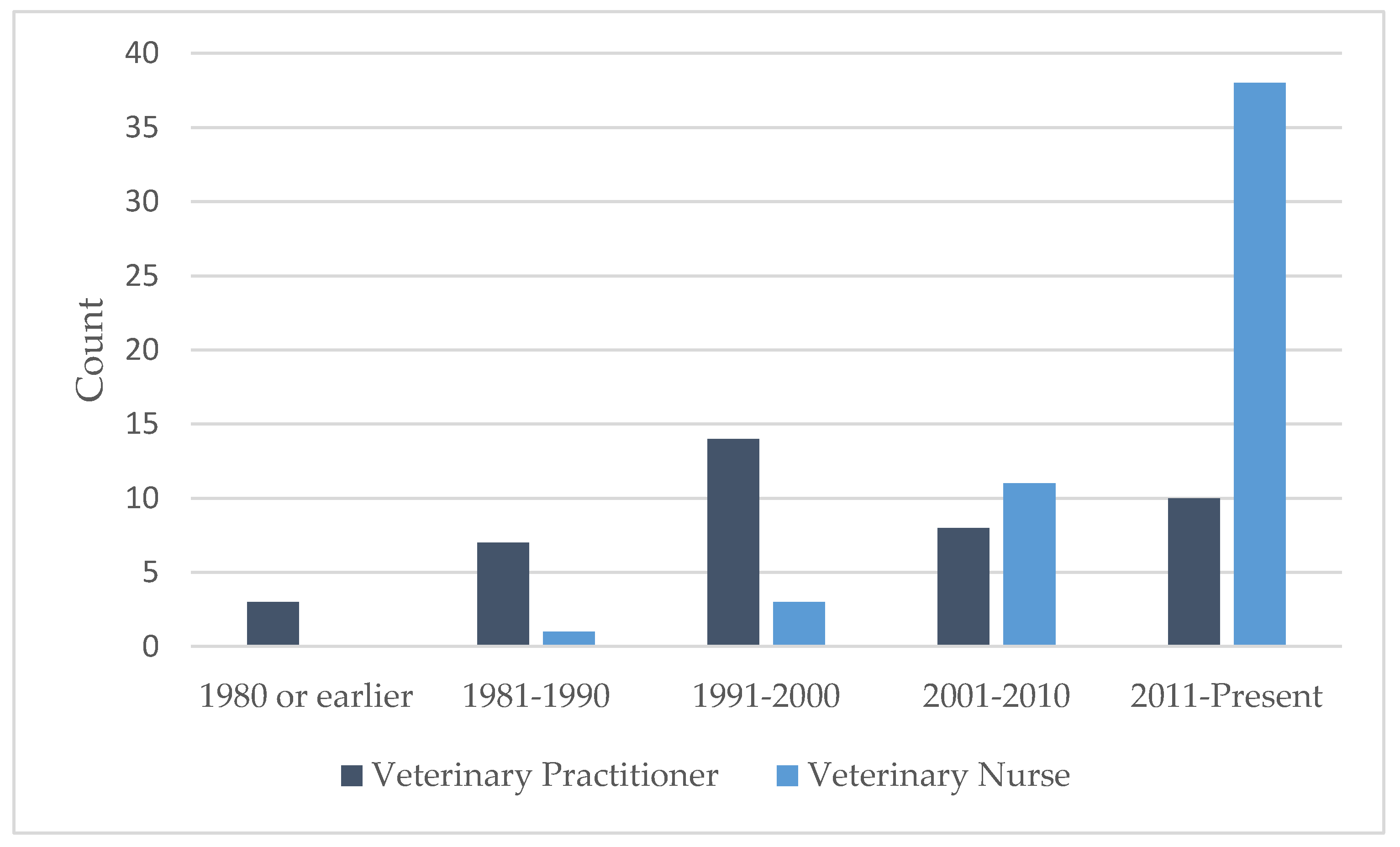

3.1. Respondent Demographics

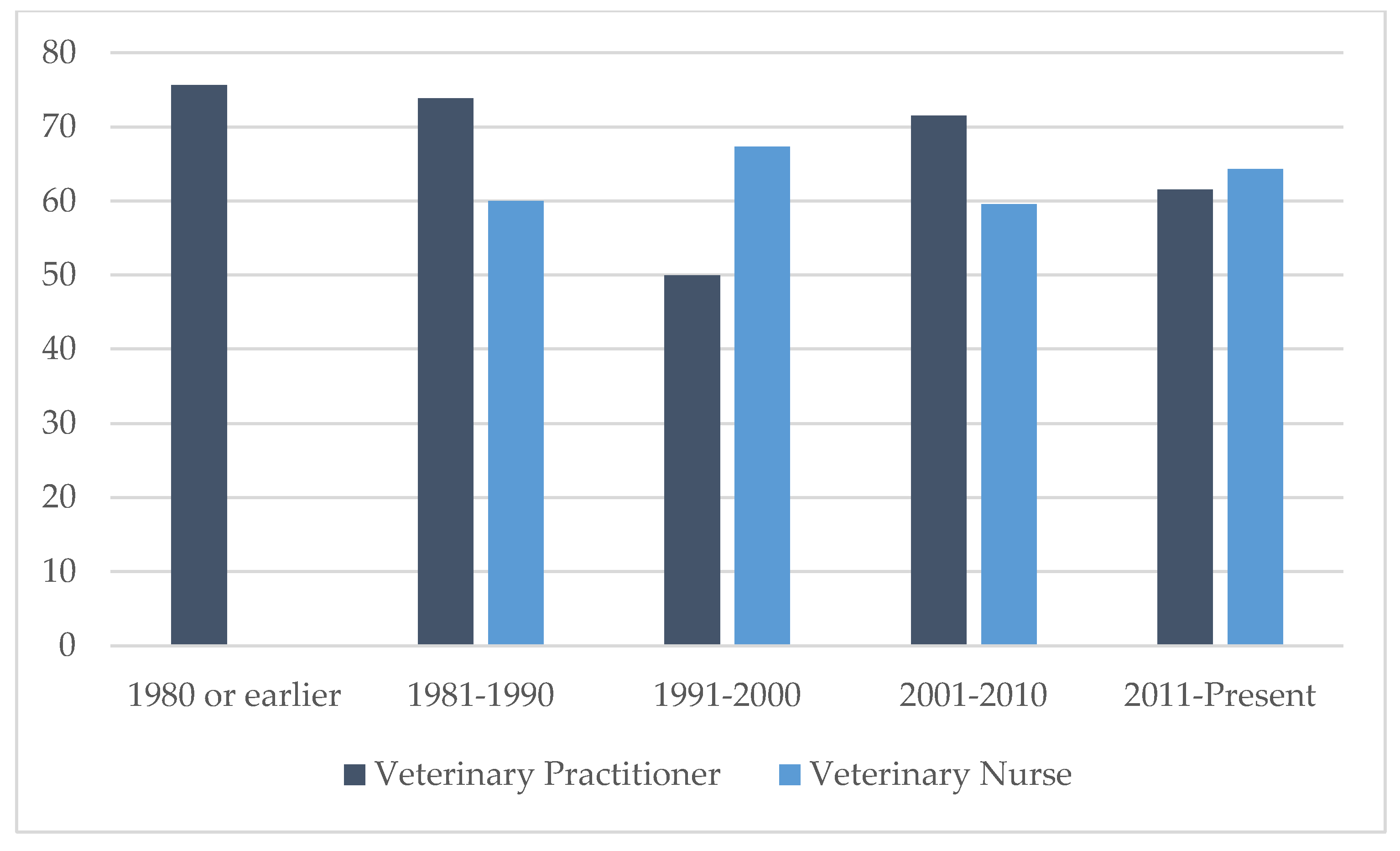

3.2. Confidence with Addressing Cats’ Behavioural Problems

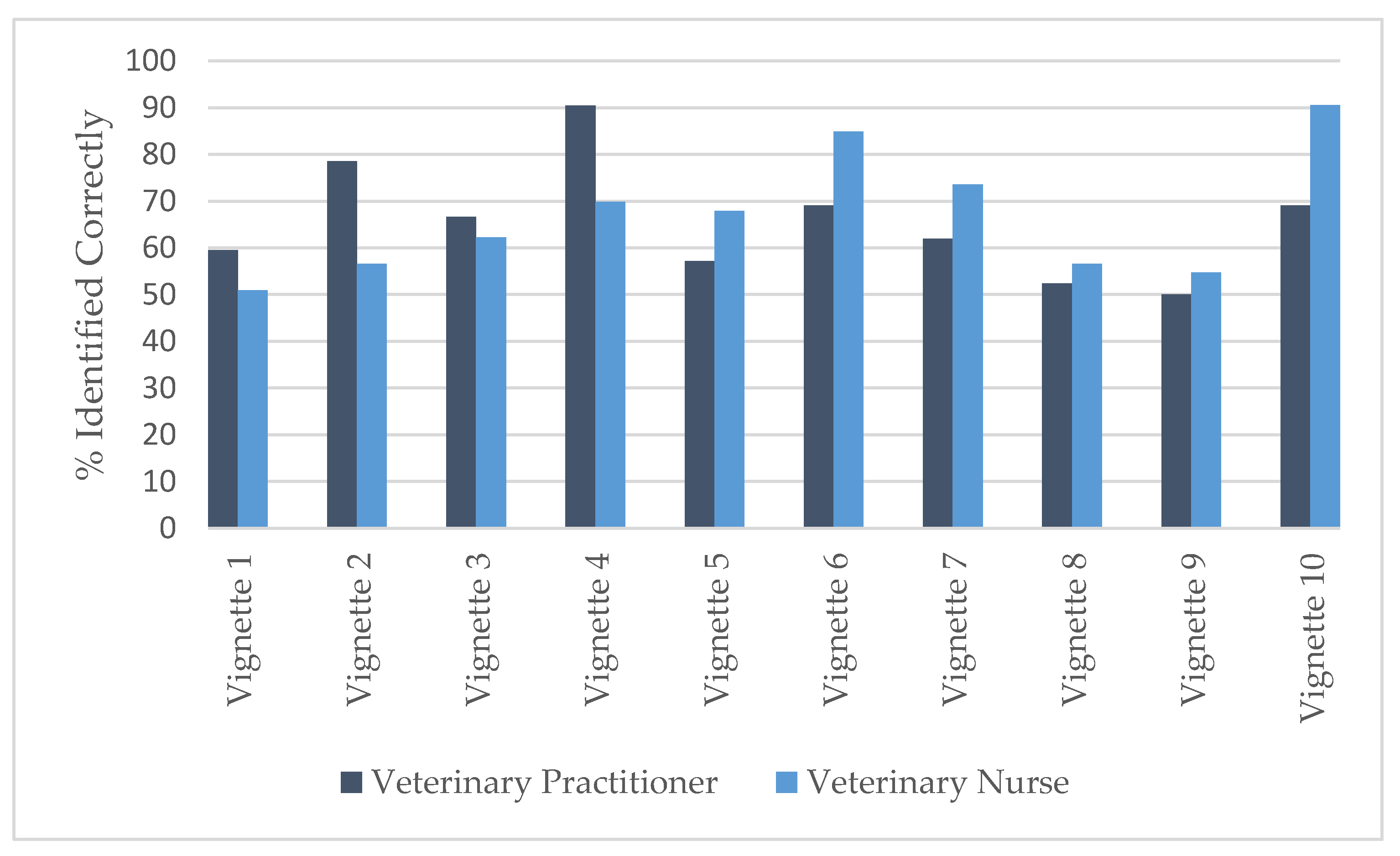

3.3. Likelihood of Correctly Categorising Vignettes

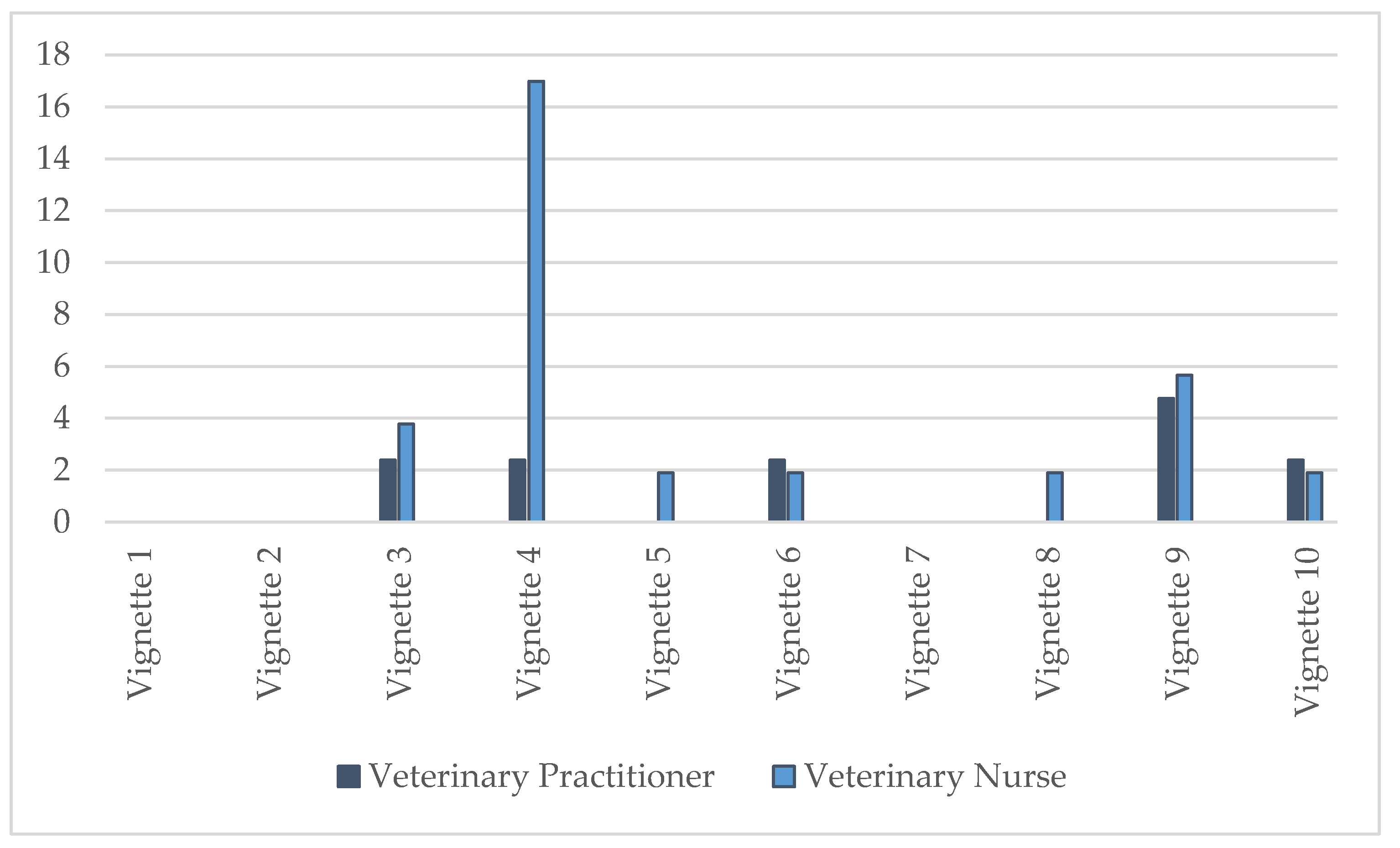

3.4. Comparison by Profession

3.5. “Cat Friendly” Practices

4. Discussion

4.1. Veterinary Demographic

4.2. Confidence with Addressing Cats’ Behavioural Problems

4.3. Likelihood of Achieving Best Outcome

4.4. Knowledge Gaps

4.5. Availability of Cat Friendly Practices

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golden, O.; Hanlon, A.J. Towards the development of day one competences in veterinary behaviour medicine: Survey of veterinary professionals experience in companion animals practice in Ireland. Ir. Vet. J. 2018, 71, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, L.R.; Hellyer, P.W.; Rishniw, M.; Schoenfeld-Tacher, R. Veterinary behavior: Assessment of veterinarians’ training, experience, and comfort level with cases. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2018, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Orihuela, A.; Strappini-Asteggiano, A.; Cajiao-Pachon, M.N.; AgueraBuendia, E.; Mora-Medina, P.; Ghezzi, M.; Alonso-Spilsbury, M. Teaching animal welfare in veterinary schools in Latin America. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Med. 2018, 6, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shivley, C.B.; Garry, F.B.; Kogan, L.R.; Grandin, T. Survey of animal welfare, animal behavior, and animal ethics courses in the curricula of AVMA council on education-accredited veterinary colleges and schools. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2016, 248, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoe, P.; Corr, S.; Palmer, C. Companion Animal Ethics; Luentokokoelma; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 2013, pp. 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Gardiner, A. The development and role of the veterinary and other professions. In Companion Animal Ethics, 1st ed.; Sandoe, P., Corr, S., Palmer, C., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; p. 26. [Google Scholar]

- PAW PDSA Animal Wellbeing Report 2018. Available online: https://www.pdsa.org.uk/media/4371/paw-2018-full-web-ready.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2019).

- Shalvey, E.; McCorry, M.; Hanlon, A. Exploring the understanding of best practice approaches to common dog behaviour problems by veterinary professionals in Ireland. Ir. Vet. J. 2019, 72, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerle, M.; Horst, C.; Levine, E.; Overall, K.; Radosta, L.; Rafter-Ritchie, M.; Yin, S. 2015 AAHA Canine and Feline Behavior Management Guidelines. J. Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2015, 51, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wassink-van der Schot, A.A.; Day, C.; Morton, J.M.; Rand, J.; Phillips, C.J.C. Risk factors for behavior problems in cats presented to an Australian companion animal behavior clinic. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 14, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horwitz, D. Common feline problem behaviors urine spraying. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelow, E. Diagnosing behaviour problems a guide for practitioners. Vet. Clin. Small Anim. 2018, 48, 339–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T. Advice for veterinary professionals. In Practical Feline Behaviour: Understanding Cat Behaviour and Improving Welfare, 1st ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2018; pp. 152–179. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J.A.; Hanlon, A.; More, S.J.; Wall, P.G.; Duggan, V. Policy Delphi with vignette methodology as a tool to evaluate the perception of equine welfare. Vet. J. 2009, 181, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhaes-Sant’Ana, M.; Hanlon, A.J. Straight from the Horse’s Mouth: Using vignettes to support student learning in veterinary ethics. J. Vet. Med. Educ. 2016, 43, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amat, M.; Camps, T.; Manteca, X. Stress in owned cats: Behavioural changes and welfare implications. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2016, 18, 577–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadek, T.; Hamper, B.; Horwitz, D.; Rodan, I.; Rowe, E.; Sundahl, E. Addressing behavioral needs to improve feline health and wellbeing. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2018, 20, 1049–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, S. Common feline problem behaviours unacceptable indoor elimination. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2019, 21, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Titeux, E.; Gilbert, C.; Briand, A.; Cochet-Faivre, N. From feline idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis to feline behavioral ulcerative dermatitis: Grooming repetitive behaviors indicators of poor welfare in cats. Front. Vet. Sci. 2018, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2017; Available online: https://www.R-project.org (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Sanchez-Vizcaino, F.; Noble, P.M.; Jones, P.H.; Menacere, T.; Buchan, I.; Reynolds, S.; Dawson, S.; Gaskell, R.M.; Everitt, S.; Radfor, A.D. Demographics of dogs, cats, and rabbits attending veterinary practices in Great Britain as recorded in the electronic health records. BMC Vet. Res. 2017, 13, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volk, J.O.; Felsted, K.E.; Thomas, J.G.; Siren, C.W. Executive summary of the Bayer veterinary care usage study. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2011, 238, 1275–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Carroll, A.; Montrose, T. Environmental methods used by veterinary centres to reduce stress of cats and dogs during veterinary visits. Vet. Nurs. J. 2019, 10, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodan, I.; Sundahl, E.; Carney, H.; Gagnon, A.; Heath, S.; Landsberg, G.; Seksel, K.; Yin, S. AAFP and ISFM Feline Friendly Handling Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2011, 13, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, S. How to reduce stress in the veterinary waiting room. Vet. Nurs. J. 2013, 4, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.K.F. Minimising Stress for Patients in the Veterinary Hospital: Why It Is Important and What Can Be Done about It. Vet. Sci. 2017, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endersby, S. Setting up a cat friendly clinic. Vet. Nurs. J. 2018, 9, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhant, C.; Horschlager, N.; Troxler, J. Attitudes of veterinarians and veterinary students to recommendations on how to improve dog and cat welfare in veterinary practice. J. Vet. Behav. 2019, 31, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CEVA Santé Animale Feliway Classic Diffuser. 2019. Available online: https://www.feliway.com/uk/Products/FELIWAY-CLASSIC-Diffuser (accessed on 28 August 2019).

- Ellis, S.L.H.; Rodan, I.; Carney, H.C.; Heath, S.; Rochlitz, I.; Shearburn, L.D.; Sundahl, E.; Westropp, J.L. AAFP and ISFM Feline Environmental Needs Guidelines. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2013, 15, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Theme | Vignette | Likelihood to Achieve Best Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Inappropriate Toileting | While at reception after a check-up, Sally asks the vet nurse, Ciara, why her cat has stopped using the litter box saying, “We’ve been having some work done on the house, but he won’t even go when the workers aren’t there.” Ciara tells Sally, “Try moving the litter box to a dark, quiet room away from the work and clean up accidents with any ammonia based cleaner. The harsh smell will encourage him to go elsewhere.” | Unlikely |

| 2. Spraying | John brings in his four year old unneutered cat, Marmalade, because he’s begun spraying next to the back door saying, “I’ve also recently noticed the neighbour’s cat sitting on the garden wall.” The vet advises John to have Marmalade neutered and says, “You should also make sure to clean the spots well with Dettol, spray the area with Feliway and put something up on the garden wall to block the neighbour’s cat.” | Likely |

| 3. Destructive Behaviour | Mary brings in her two year old DSH, Penny, for her yearly check-up. She tells the vet, “Penny won’t quit trying to scratch my new couch instead of her scratching posts. What should I do?” The vet replies, “Spot test and then spray your couch with Feliway to discourage the scratching. You can also use a catnip spray on the scratching posts to encourage Penny to scratch there instead.” | Likely |

| 4. Self-mutilation | Anne brings her elderly cat, Bob, in on a repeat visit for a single, large, crusted, non-healing, self-induced ulcer located between the scapulae. Past examinations have ruled out bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections as well as other common allergens. Due to the unique presentation of the ulcer and having ruled out most purely medical reasons, the vet diagnoses idiopathic ulcerative dermatitis and tells Anne, “Just keep wrapping the area each time it happens and the ulcer will heal on its own.” | Unlikely |

| 5. Anxiety—Child related | While purchasing flea treatment for her cat, Mary asks the vet nurse, Darren, for advice. “Whenever my nieces come over, my cat spends the whole day avoiding them and will bolt and then vomit up his dinner. What can I do to reduce his anxiety around them? He never settles.” Darren says, “Put up some baby gates, blocking off part of your house from your nieces for the cat. Make sure to feed him in one of these rooms.” | Likely |

| 6. Anxiety—Moving home | During a routine clinical examination, Lorraine asks the vet what she can do to reduce her cat’s anxiety during an upcoming move. The vet suggests, “Get some Feliway diffusers and use them in both houses for at least a few days before the move.” | Likely |

| 7. Fear—Loud Noises | Coming out of a routine consult, Sara asks the vet nurse “Socks always gets so scared of the fireworks. With New Year’s Eve this weekend, is there anything I can do?” The vet nurse tells Sara,“ Make sure to stay in so that you can cuddle and reassure him that everything will be okay.” | Unlikely |

| 8. Fear—Strangers | Clare recently adopted a twelve-week-old kitten, Tommy. After bringing him in for vaccinations and an exam, she asks the vet for advice because Tommy is nervous around guests. The vet says, “The best way to solve this is to introduce Tommy to as many different people as possible so that he gets used to it.” | Unlikely |

| 9. Aggression—Play related | Vanessa has brought her six month old kitten Freckles to the vet for vaccination. She asks how to stop Freckles from attacking her feet. The vet tells Vanessa, “Get a water gun or spray bottle and spray him whenever he jumps on your feet to discourage him.” | Unlikely |

| 10. Aggression—Cat/Cat resource-based aggression | Jo has brought in her two year old cats, Fred and George, for their annual check-up. She asks the vet how to stop Fred from pouncing on and attacking George when he’s done using the litter box and says, “They’ve used the same litter box since they were kittens. It’s only become a problem the last couple of months.” The vet offers her advice, “You need at least two litter boxes for two cats. Try putting in another one, preferably in an area George frequents.” | Likely |

| Vignette | Best Outcome | Most Frequent Response | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Veterinary Practitioner | Veterinary Nurse | Overall | ||

| 1. Inappropriate Toileting | Unlikely | 59.5% Unlikely | 50.9% Unlikely | 54.7% Unlikely |

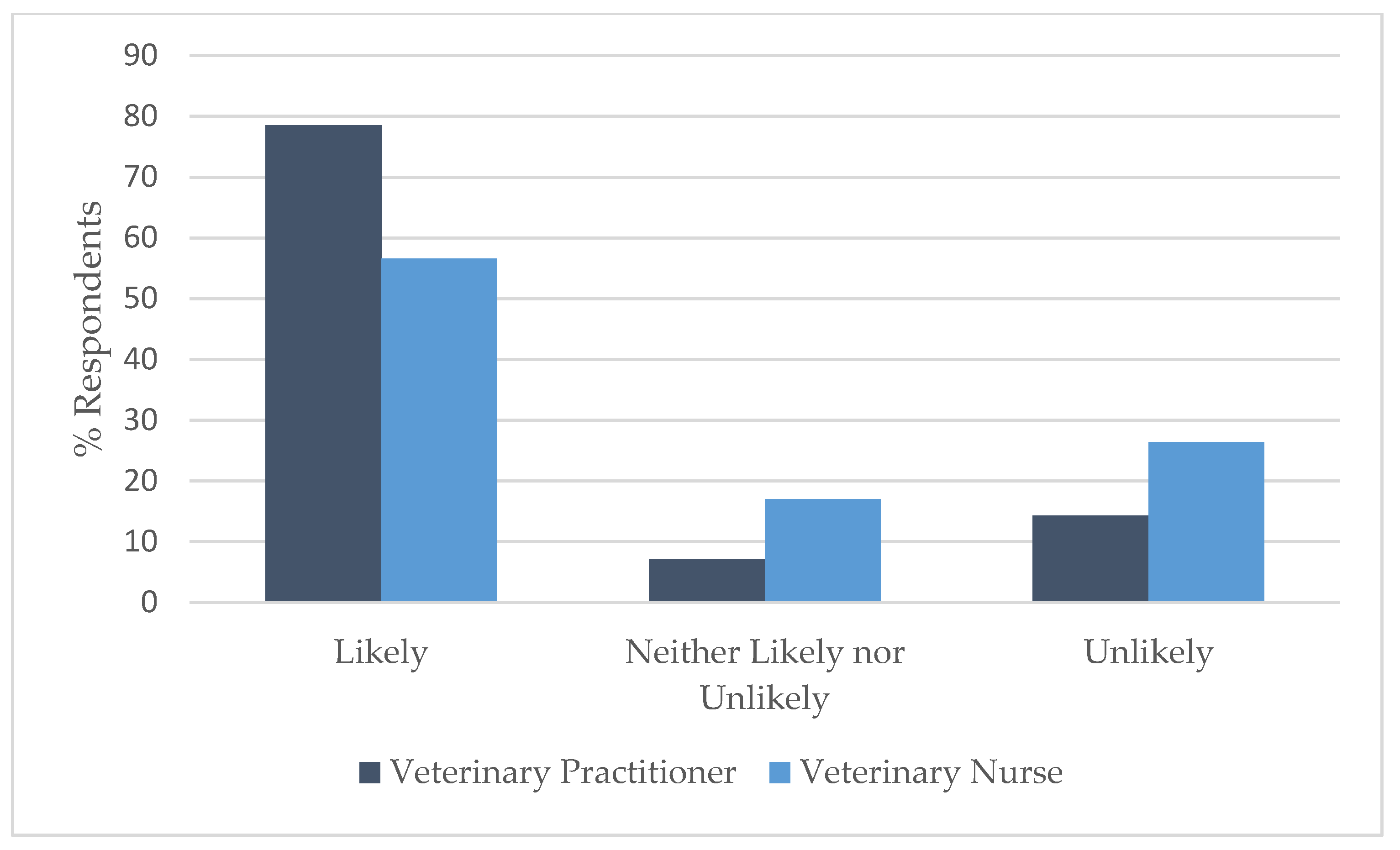

| 2. Spraying | Likely | 78.6% Likely | 56.6% Likely | 66.3% Likely |

| 3. Destructive Behaviour | Likely | 66.7% Likely | 62.3% Likely | 64.2% Likely |

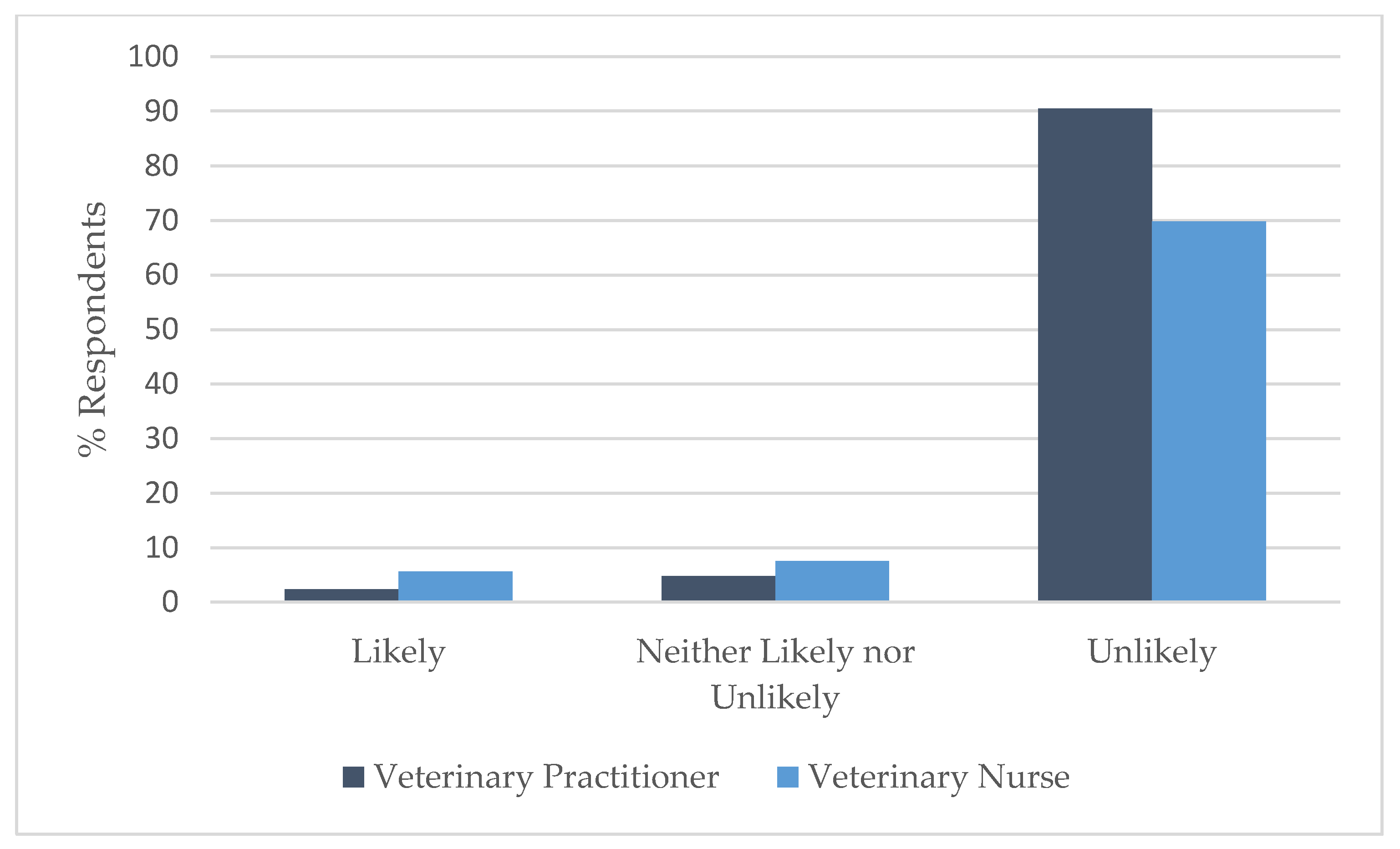

| 4. Self-mutilation | Unlikely | 90.5% Unlikely | 69.8% Unlikely | 77.9% Unlikely |

| 5. Anxiety—Child related | Likely | 57.1% Likely | 67.9% Likely | 62.1% Likely |

| 6. Anxiety—Moving home | Likely | 69.0% Likely | 84.9% Likely | 76.8% Likely |

| 7. Fear—Loud Noises | Unlikely | 61.9% Unlikely | 73.6% Unlikely | 67.4% Unlikely |

| 8. Fear—Strangers | Unlikely | 52.4% Unlikely | 56.6% Unlikely | 53.7% Unlikely |

| 9. Aggression—Play related | Unlikely | 50.0% Unlikely | 54.7% Unlikely | 52.6% Unlikely |

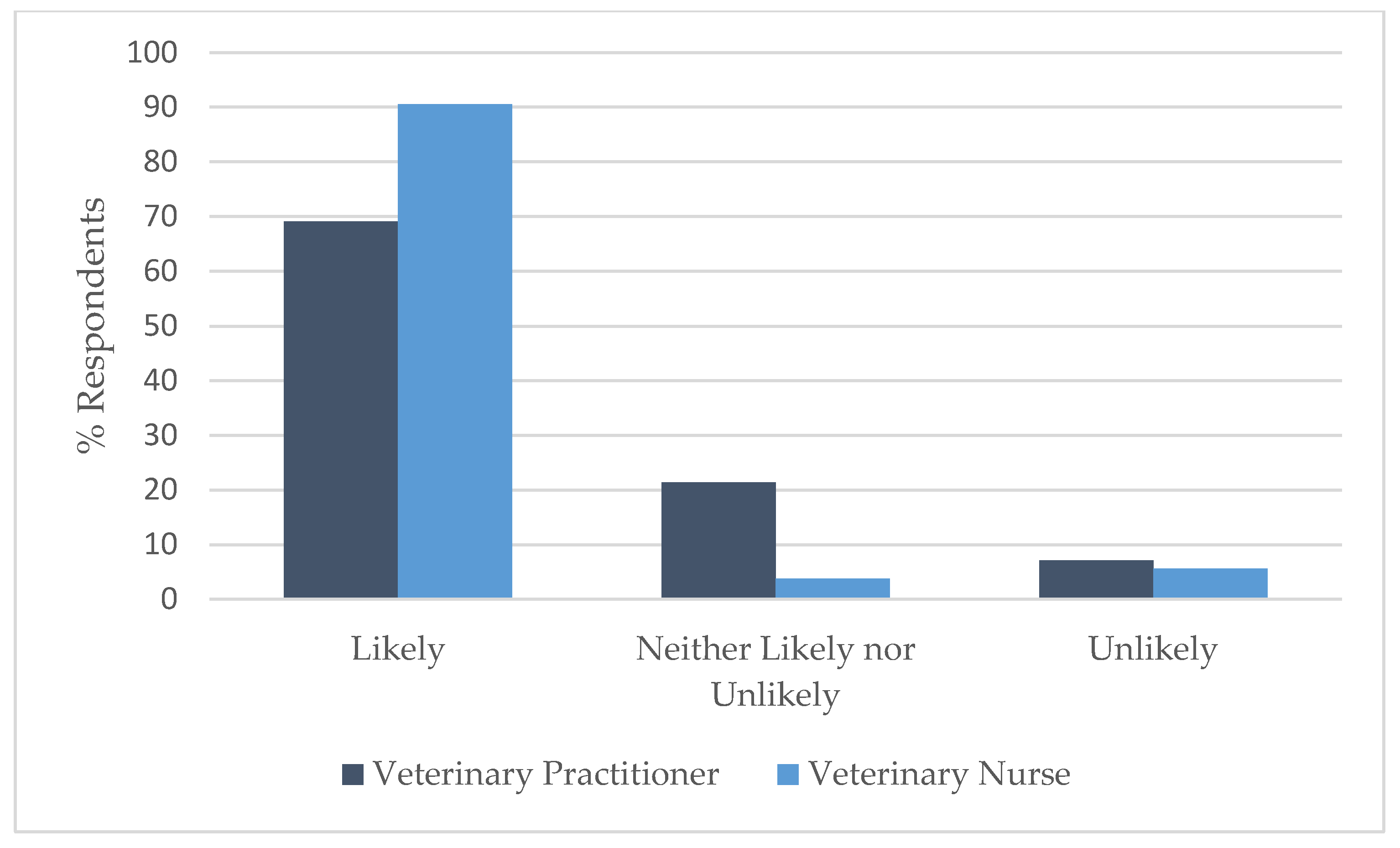

| 10. Aggression—Cat/Cat resource-based aggression | Likely | 69.0% Likely | 90.6% Likely | 81.1% Likely |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Goins, M.; Nicholson, S.; Hanlon, A. Veterinary Professionals’ Understanding of Common Feline Behavioural Problems and the Availability of “Cat Friendly” Practices in Ireland. Animals 2019, 9, 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121112

Goins M, Nicholson S, Hanlon A. Veterinary Professionals’ Understanding of Common Feline Behavioural Problems and the Availability of “Cat Friendly” Practices in Ireland. Animals. 2019; 9(12):1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121112

Chicago/Turabian StyleGoins, Matt, Sandra Nicholson, and Alison Hanlon. 2019. "Veterinary Professionals’ Understanding of Common Feline Behavioural Problems and the Availability of “Cat Friendly” Practices in Ireland" Animals 9, no. 12: 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121112

APA StyleGoins, M., Nicholson, S., & Hanlon, A. (2019). Veterinary Professionals’ Understanding of Common Feline Behavioural Problems and the Availability of “Cat Friendly” Practices in Ireland. Animals, 9(12), 1112. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121112