Salivary Vasopressin as a Potential Non–Invasive Biomarker of Anxiety in Dogs Diagnosed with Separation–Related Problems

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Study Setting

2.2. Study Protocol

2.3. Parameters Recorded: Behavioral Responses

2.4. Parameters Recorded: Endocrine Responses

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

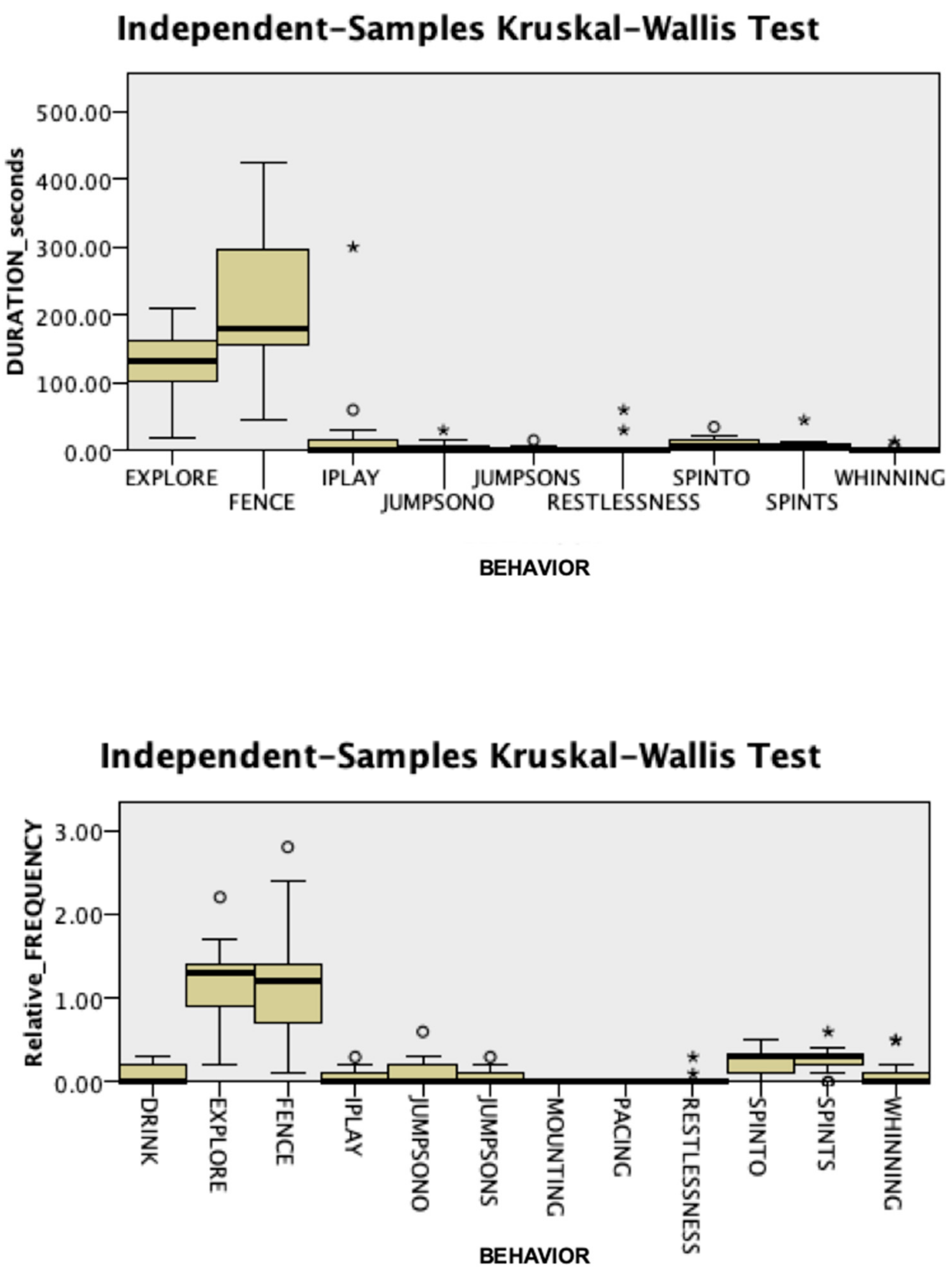

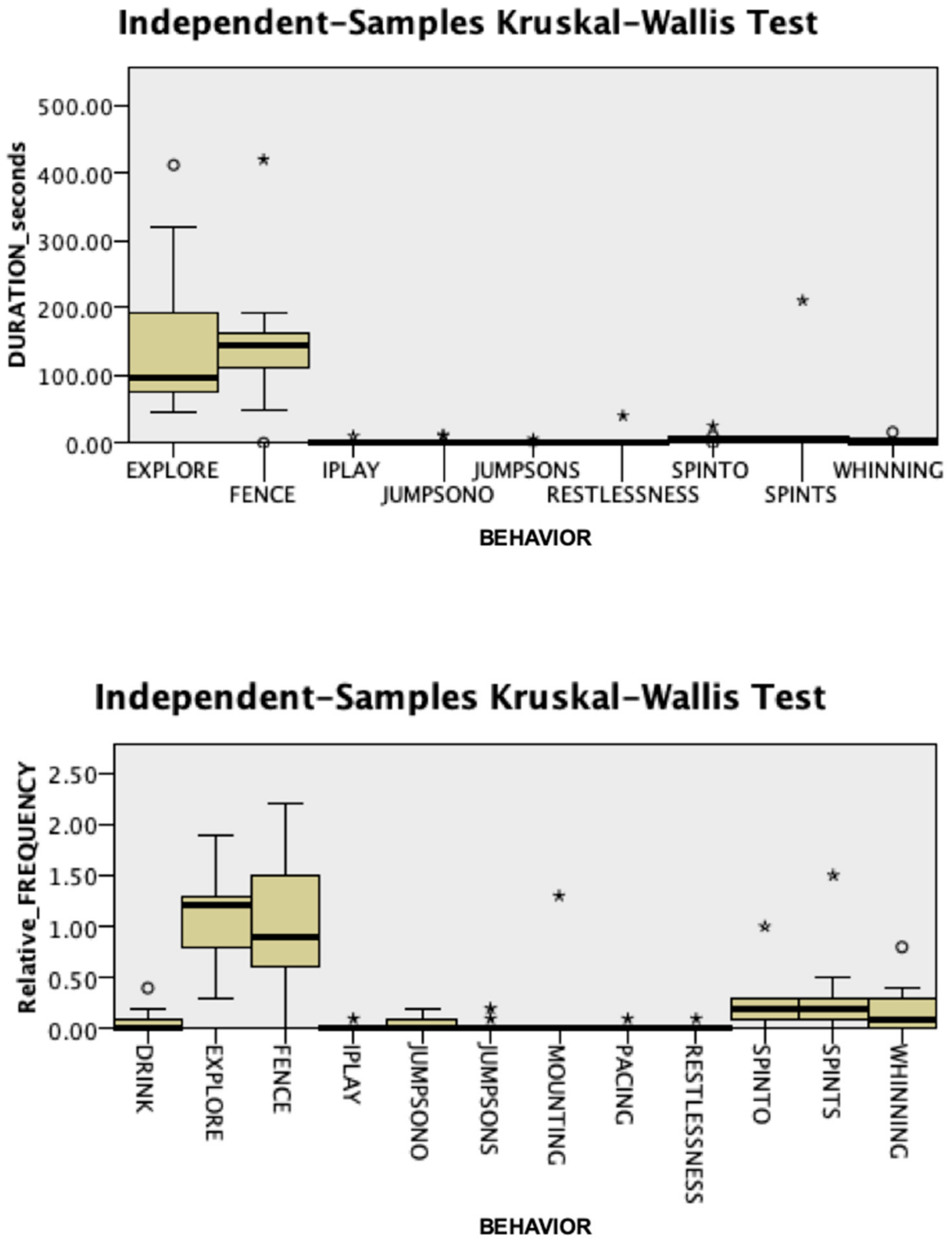

3.1. Behavioral Responses

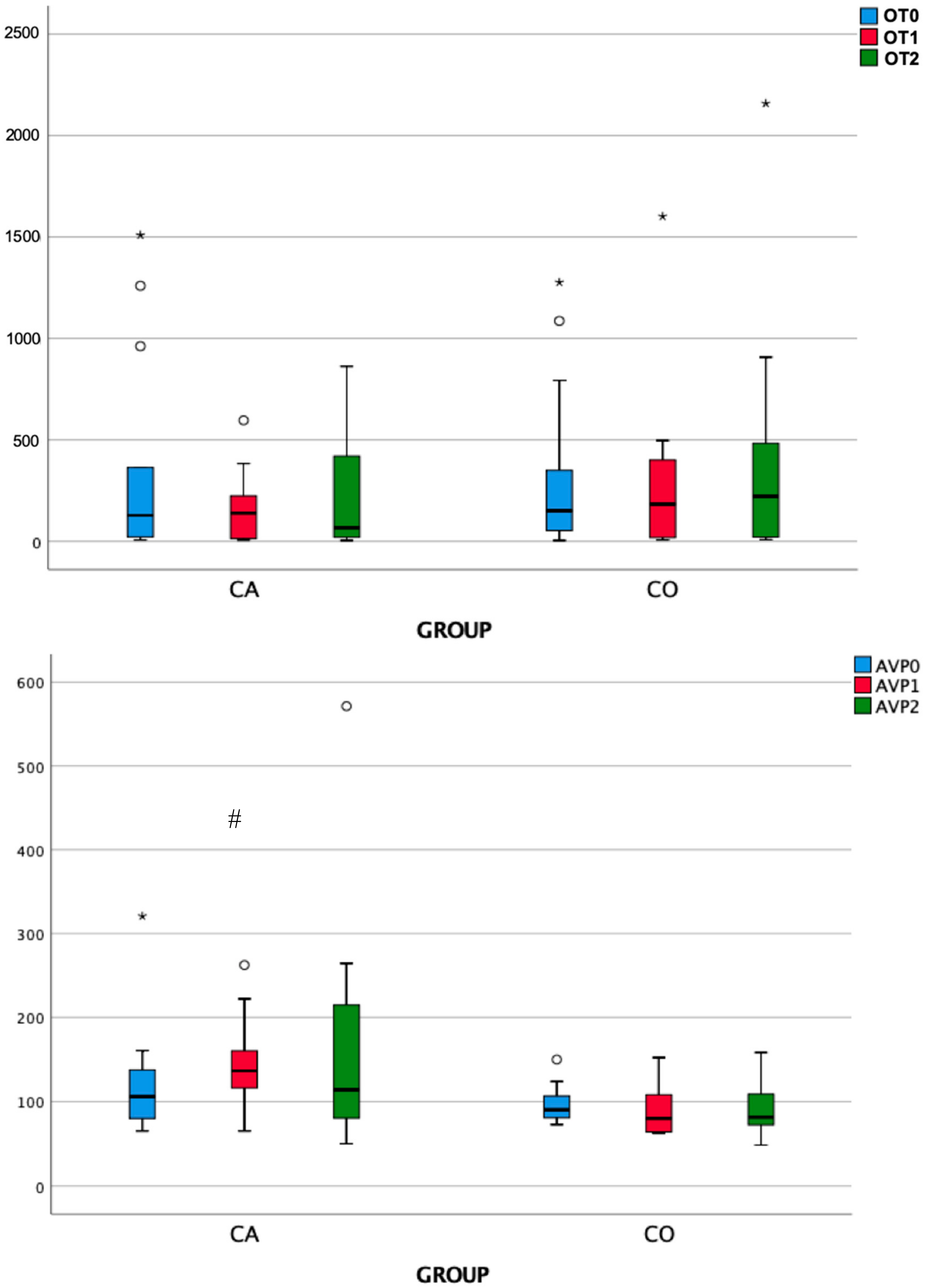

3.2. Endocrine Responses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carter, C.S. The Role of Oxytocin and Vasopressin in Attachment. Psychodyn. Psych. 2017, 45, 499–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariti, C.; Ricci, E.; Carlone, B.; Moore, J.L.; Sighieri, C.; Gazzano, A. Dog attachment to man: A comparison between pet and working dogs. J. Vet. Behav. 2013, 8, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehn, T.; Handlin, L.; Uvnäs–Moberg, K.; Keeling, L.J. Dogs’ endocrine and behavioural responses at reunion are affected by how the human initiates contact. Physiol. Behav. 2014, 124, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parthasarathy, V.; Crowell–Davis, S.L. Relationship between attachment to owners and separation anxiety in pet dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). J. Vet. Behav. 2006, 1, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konok, V.; Dóka, A.; Miklósi, Á. The behavior of the domestic dog (Canis familiaris) during separation from and reunion with the owner: A questionnaire and an experimental study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2011, 135, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palestrini, C.; Previde, E.P.; Spiezio, C.; Verga, M. Heart rate and behavioural responses of dogs in the Ainsworth’s Strange Situation: A pilot study. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2005, 94, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, L.; Bracci–Laudiero, L.; Allevat, E.; Lambiase, A.; Micera, A.; Tirassa, P. Emotional stress induced by parachute jumping enhances blood nerve growth factor levels and the distribution of nerve growth factor receptors in lymphocytes (str/nxet/hormone). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 10440–10444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aloe, L.; Allevat, E.; Bohm, A.; Levi–Montalcini, R. Aggressive behavior induces release of nerve growth factor from mouse salivary gland into the bloodstream (submaxillary salivary gland/adrenal gland). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 6184–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T.; Lin, S.; DeVries, C.; Lambert, K. Coping strategies in male and female rats exposed to multiple stressors. Physiol. Behav. 2003, 78, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, I.D.; Landgraf, R. Balance of brain oxytocin and vasopressin: Implications for anxiety, depression, and social behaviors. Trends Neurosci. 2012, 35, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uvnäs–Moberg, K. Oxytocin may mediate the benefits of positive social interaction and emotions. Psychoneuroendocrinology 1998, 23, 819–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wotjak, C.; Kubota, M.; Liebsch, G.; Montkowski, A.; Holsboer, F.; Neumann, I.; Landgraf, R. Release of vasopressin within the rat paraventricular nucleus in response to emotional stress: A novel mechanism of regulating adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion? Soc. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 7725–7732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, E.L.; Gesquiere, L.R.; Gee, N.R.; Levy, K.; Martin, W.L.; Carter, C.S. Effects of Affiliative Human–Animal Interaction on Dog Salivary and Plasma Oxytocin and Vasopressin. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagasawa, M.; Mitsui, S.; En, S.; Ohtani, N.; Ohta, M.; Sakuma, Y.; Onaka, T.; Mogi, K.; Kikusui, T. Oxytocin–gaze positive loop and the coevolution of human–dog bonds. Science 2015, 348, 333–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hydbring–Sandberg, E.; von Walter, L.; Höglund, K.; Svartberg, K.; Forkman, L.B.S. Physiological reactions to fear provocation in dogs. J. Endocrinol. 2004, 180, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, E.L.; Gesquiere, L.R.; Gruen, M.E.; Sherman, B.L.; Martin, W.L.; Carter, C.S. Endogenous Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and Aggression in Domestic Dogs. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, K.L. Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Dogs and Cats; Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; ISBN 9780323240659. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, A. Dogs behaving badly–Canine separation disorder research. Vet. Pr. 1999, 31, 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg, G.; Hunthausen, W.; Ackerman, L. Fear and Phobias, Separation Anxiety. In Handbook of Behavior Problems of the Dog and Cat, 2nd ed.; Landsberg, G.M., Hunthausen, W.L., Ackerman, L., Eds.; Saunders Company: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2003; pp. 258–267. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell, E.; Casey, R.; Bradshaw, J. Controlled trial of behavioural therapy for separation–related disorders in dogs. Vet. Rec. 2006, 158, 551–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overall, K.L.; Dunham, A.E.; Juarbe–Diaz, S.V. Phenotypic determination of noise reactivity in 3 breeds of working dogs: A cautionary tale of age, breed, behavioral assessment, and genetics. J. Vet. Behav. 2016, 16, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tami, G.A.G. Description of the behaviour of domestic dog (Canis familiaris) by experienced and inexperienced people. Appl. Anim. Behav. 2009, 120, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariti, C.; Gazzano, A.; Moore, J.; Baragli, P. Perception of dogs’ stress by their owners. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2012, 7, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagiannis, C.I.; Burman, O.H.; Mills, D.S. Dogs with separation–related problems show a “less pessimistic” cognitive bias during treatment with fluoxetine (ReconcileTM) and a behaviour modification plan. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradshaw, J.; McPherson, J.; Casey, R.; Larter, I. Aetiology of separation–related behaviour in domestic dogs. Vet. Rec. 2002, 151, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.; Pereira, J.; Paixão, R. Exploratory study of separation anxiety syndrome in apartment dogs. Cienc. Rural. 2010, 40, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statista Number of dogs in the United States from 2000 to 2017 (in millions). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/198100/dogs–in–the–united–states–since–2000/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Statista Number of dogs in the European Union in 2017, by country (in 1000s). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/414956/dog–population–european–union–eu–by–country/ (accessed on 15 July 2019).

- Diesel, G.; Brodbelt, D.; Pfeiffer, D.U. Characteristics of Relinquished Dogs and Their Owners at 14 Rehoming Centers in the United Kingdom. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 2010, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New, J.C., Jr.; Salman, M.D.; Scarlett, J.M.; Kass, P.H.; Vaughn, J.A.; Scherr, S.; Kelch, W.J. Moving: Characteristics of Dogs and Cats and Those Relinquishing Them to 12 U.S. Animal Shelters. J. Appl. Anim. Welf. Sci. 1999, 2, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLean, E.; Gesquiere, L.; Gee, N.; Levy, K. Validation of salivary oxytocin and vasopressin as biomarkers in domestic dogs. J. Neurosci. 2017, 293, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Farrell, V. Owner attitudes and dog behaviour problems. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 1997, 52, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, C.; Pirrone, F.; Balzarotti, F.; Faustini, M.; Pierantoni, L.; Albertini, M. Evaluation of physiological and behavioral stress–dependent parameters in agility dogs. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2011, 6, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirrone, F.; Ripamonti, A.; Garoni, E.C.; Stradiotti, S.; Albertini, M. Measuring social synchrony and stress in the handler–dog dyad during animal–assisted activities: A pilot study. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2017, 21, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prato–Previde, E.; Spiezio, C.; Sabatini, F.; Custance, D.M. Is the dog–human relationship an attachment bond? An observational study using Ainsworth’s strange situation. Behaviour 2003, 140, 225–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, E. Video analysis of adult dogs when left home alone. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2013, 8, 412–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Gácsi, M.; Miklósi, Á.; Virányi, Z.; Kubinyi, E.; Csányi, V. Attachment to humans: a comparative study on hand–reared wolves and differently socialized dog puppies. Anim. Behav. 2005, 70, 1367–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.W. Life is lognormal! What to do when your data does not follow a normal distribution. Anaesthesia 2016, 71, 1363–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Hara, R.B.; Kotze, D.J. Do not log-transform count data. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2010, 1, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannigan, G.; Dodman, N.H. Risk factors and behaviors associated with separation anxiety in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2001, 219, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, Y.; Houpt, K.A.; Scarlett, J.M. Evaluation of treatments for separation anxiety in dogs. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 2000, 217, 342–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, M.D.S. Individual Differences in Strange–Situational Behaviour of One–Year–Olds. In Determinants of Infant Behavior (Vol. 4); Foss, B.M., Ed.; Methuen: London, UK, 1969; pp. 111–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bard, K.A.; Nadler, R.D. The effect of peer separation in young chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Am. J. Primatol. 1983, 5, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, I.C.; Rosenblum, L.A. Effects of separation from mother on the emotional behavior of infant monkeys. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1969, 159, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topál, J.; Miklósi, Á.; Csányi, V.; Dóka, A. Attachment Behavior in Dogs (Canis familiaris): A New Application of Ainsworth’s (1969) Strange Situation Test. J. Comp. Psychol. 1998, 112, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White–Traut, R.; Watanabe, K.; Pournajafi–Nazarloo, H.; Schwertz, D.; Bell, A.; Carter, C.S. Detection of salivary oxytocin levels in lactating women. Dev. Psychobiol. 2009, 51, 367–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiira, K.; Lohi, H. Early Life Experiences and Exercise Associate with Canine Anxieties. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludwig, M.; Leng, G. Dendritic peptide release and peptide–dependent behaviours. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006, 7, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, E.L.; Caldwell, H.K. The vasopressin 1b receptor and the neural regulation of social behavior. Horm. Behav. 2012, 61, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baribeau, D.A.; Anagnostou, E. Oxytocin and vasopressin: Linking pituitary neuropeptides and their receptors to social neurocircuits. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pow, D.; Morris, J. Dendrites of hypothalamic magnocellular neurons release neurohypophysial peptides by exocytosis. Neuroscience 1989, 32, 435–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knobloch, H.S.; Charlet, A.; Hoffmann, L.C.; Eliava, M.; Khrulev, S.; Cetin, A.H.; Osten, P.; Schwarz, M.K.; Seeburg, P.H.; Stoop, R.; et al. Evoked Axonal Oxytocin Release in the Central Amygdala Attenuates Fear Response. Neuron 2012, 73, 553–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, R. Involvement of the brain oxytocin system in stress coping: Interactions with the hypothalamo–pituitary–adrenal axis. Trends Neurosci. 2002, 35, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisman, O.; Schneiderman, I.; Zagoory–Sharon, O.; Feldman, R. Salivary vasopressin increases following intranasal oxytocin administration. Peptides 2013, 40, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carson, D. Plasma vasopressin concentrations positively predict cerebrospinal fluid vasopressin concentrations in human neonates. Peptides 2014, 61, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griebel, G.; Beeské, S.; Stahl, S.M. The Vasopressin V 1b Receptor Antagonist SSR149415 in the Treatment of Major Depressive and Generalized Anxiety Disorders: Results From 4 Randomized, Double–Blind, Placebo–Controlled Studies. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2012, 73, 1403–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iijima, M.; Yoshimizu, T.; Shimazaki, T.; Tokugawa, K.; Fukumoto, K.; Kurosu, S.; Kuwada, T.; Sekiguchi, Y.; Chaki, S. Antidepressant and anxiolytic profiles of newly synthesized arginine vasopressin V 1B receptor antagonists: TASP0233278 and TASP0390325. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 171, 3511–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannas, S.; Frank, D.; Minero, M.; Aspesi, A.; Benedetti, R.; Palestrini, C. Video analysis of dogs suffering from anxiety when left home alone and treated with clomipramine. J. Vet. Behav. Clin. Appl. Res. 2014, 9, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrichs, M.; von Dawans, B.; Domes, G. Oxytocin, vasopressin, and human social behavior. Front. Neuroendocr. 2009, 30, 548–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Hackett, P.D.; DeMarco, A.C.; Feng, C.; Stair, S.; Haroon, E.; Ditzen, B.; Pagnoni, G.; Rilling, J.K. Effects of oxytocin and vasopressin on the neural response to unreciprocated cooperation within brain regions involved in stress and anxiety in men and women. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielke, L.E.; Udell, M.A.R. The role of oxytocin in relationships between dogs and humans and potential applications for the treatment of separation anxiety in dogs. Biol. Rev. 2017, 92, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Behaviors | Description | Measured Values (F/D) |

|---|---|---|

| Social behaviors | ||

| Jumping up | Both of the dog’s forelegs were out of contact with the ground, regardless of the position of the hind legs; the dog was in proximity to a person. The dog might also be entirely on a person’s lap | F, D |

| Spontaneous interactions | Staying close to and seeking attention and physical contact (nuzzling or pawing for attention, soliciting petting) from the owner or the stranger | F, D |

| Mounting | Sexual mounting of people or inanimate objects | F, D |

| Non–social behaviors | ||

| Explore | Activity directed towards physical aspects of the environment, including sniffing, visual inspection, and gentle licking | F, D |

| Individual play | Any behavior performed vigorously or at a galloping gait and directed towards an object when clearly not interacting with any human; these play behaviors included chewing, biting, shaking from side to side, scratching or batting with the paw, chasing rolling balls, and tossing objects using the mouth | F, D |

| Standing by the fence | Standing close to the fence (<1 m), regardless of whether the face was oriented towards the exit | F, D |

| Attention oriented towards the fence | Staring fixedly at the fence, either when close to it or from a distance | F, D |

| Behaviors oriented towards the fence | All activities, resulting in physical contact with the fence, including scratching the gate with the paws, jumping on the fence, and pulling on the fence with the forelegs or mouth. | F, D |

| Restlessness | A feeling of agitation expressed by continual motion; changing the state of locomotion; digging (scratching the floor with the forepaws in a way that is similar to when dogs are digging holes) | F |

| Drinking | Taking in fluids by lapping up water from the bowl with the tongue | F |

| Whining | High-pitched vocalization | F |

| Pacing | Increased motor activity, walking or running around without exploring the environment | F |

| Group | OT0 | OT1 | OT2 | Friedman test | |

| χ2 | P | ||||

| Case | 127.87 | 138.79 | 67.04 | 3.231 | 0.199 |

| Control | 149.99 | 183 | 221.60 | 0.462 | 0.794 |

| Mann–Whitney U test | 86 | 98 | 100 | ||

| Mann–Whitney U test p | 0.960 | 0.511 | 0.448 | ||

| Group | AVP0 | AVP1 | AVP2 | Friedman test | |

| χ2 | P | ||||

| Case | 105.97 | 136.61 | 114 | 2.923 | 0.232 |

| Control | 90.40 | 80.12 | 81.53 | 3.231 | 0.199 |

| Mann–Whitney U test | 71 | 29 | 55 | ||

| Mann–Whitney U test p | 0.511 | 0.003 | 0.139 | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pirrone, F.; Pierantoni, L.; Bossetti, A.; Uccheddu, S.; Albertini, M. Salivary Vasopressin as a Potential Non–Invasive Biomarker of Anxiety in Dogs Diagnosed with Separation–Related Problems. Animals 2019, 9, 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121033

Pirrone F, Pierantoni L, Bossetti A, Uccheddu S, Albertini M. Salivary Vasopressin as a Potential Non–Invasive Biomarker of Anxiety in Dogs Diagnosed with Separation–Related Problems. Animals. 2019; 9(12):1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121033

Chicago/Turabian StylePirrone, Federica, Ludovica Pierantoni, Andrea Bossetti, Stefania Uccheddu, and Mariangela Albertini. 2019. "Salivary Vasopressin as a Potential Non–Invasive Biomarker of Anxiety in Dogs Diagnosed with Separation–Related Problems" Animals 9, no. 12: 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121033

APA StylePirrone, F., Pierantoni, L., Bossetti, A., Uccheddu, S., & Albertini, M. (2019). Salivary Vasopressin as a Potential Non–Invasive Biomarker of Anxiety in Dogs Diagnosed with Separation–Related Problems. Animals, 9(12), 1033. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9121033