Exploring the Framing of Animal Farming and Meat Consumption: On the Diversity of Topics Used and Qualitative Patterns in Selected Demographic Contexts

Abstract

:Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

- Values: opinions about what is intrinsically important;

- Norms: translation of values into rules of conduct;

- Interests: including material (economic) as well as immaterial (social, moral) interests;

- Knowledge: constructed out of experiences, facts, stories, and impressions;

- Convictions: opinions about “the way things are”, assumptions that are taken for granted.

- Behaviours: what is done: pronounced personal past and present actions, including habits and exceptions;

- Values: rational concerns: conceptualisations about what and whom is considered important and to what extent;

- Norms: what is brought forward that should be done: ideal rules of conduct imposed on the self—and possibly others;

- Feelings: affective concerns: physical sensations, states, and emotions (while framing often accompanied by gestures and facial expressions);

- Interests: recognised stakes and goals that inner drives motivate us to strive for, both material (physical, economic) as well as immaterial (social, moral, aesthetical);

- Knowledge and convictions: opinions about the way things are, about (self-)efficacy and the effects certain situations will have, associations and assumptions about what is true, including the perceived behaviours, values, norms, feelings, interests, and knowledge and convictions of others.

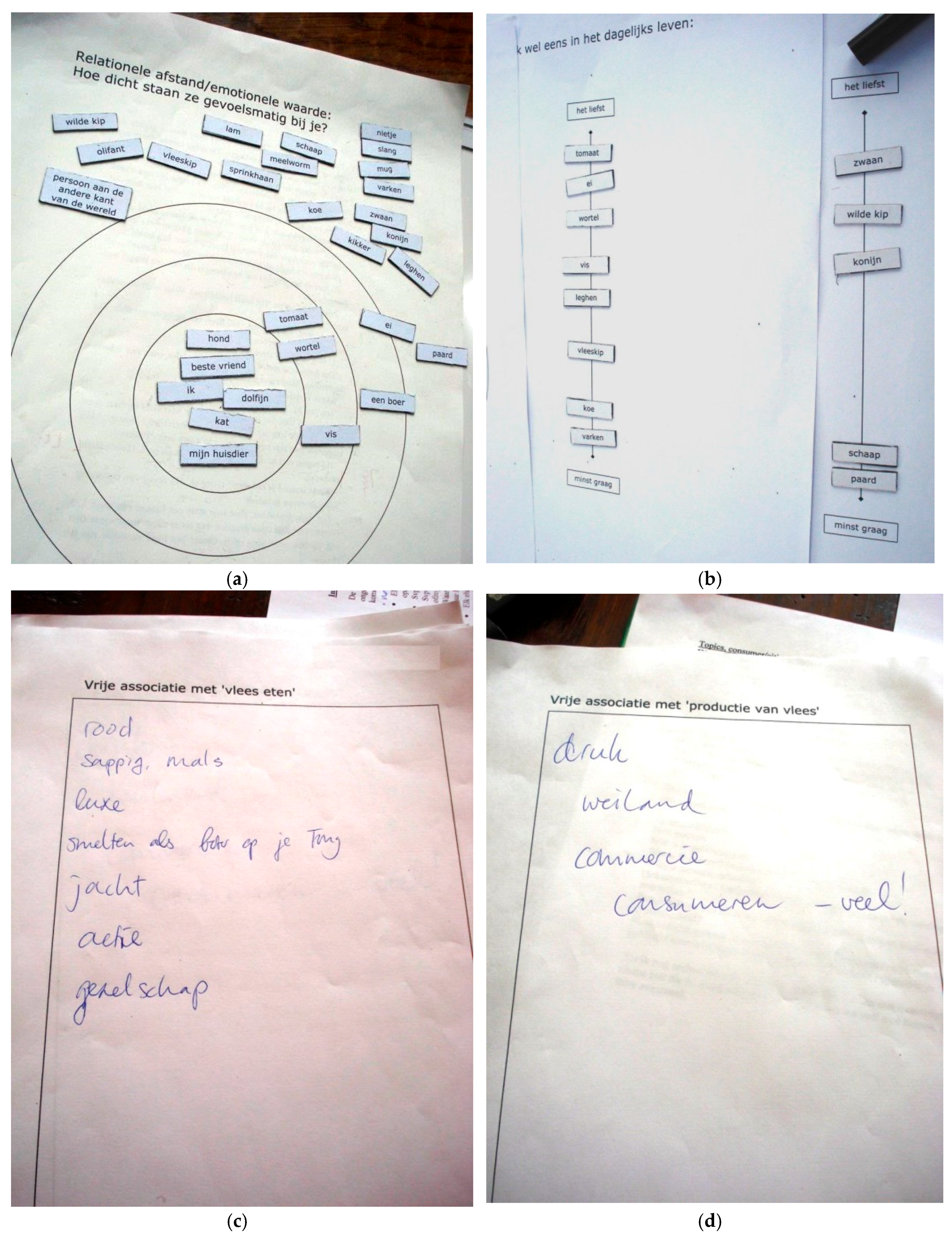

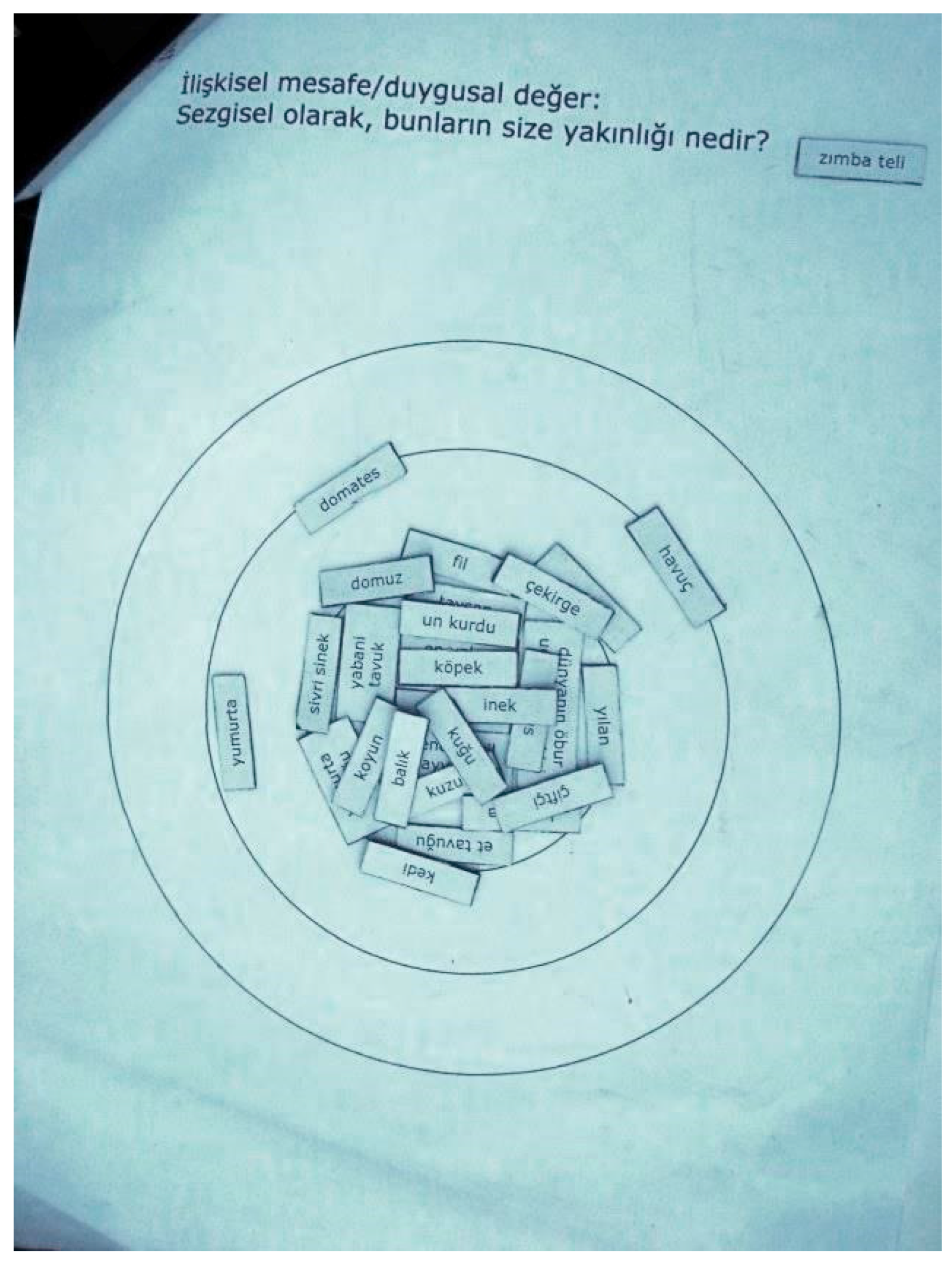

2.2. Research Design

3. Results

3.1. The Diversity of Topics Used to Frame Animal Farming and Meat Consumption

3.1.1. General Interpretation of the Use of Topics

3.1.2. Summary

3.2. Framing and Demographic Contexts in the Netherlands and Turkey

3.2.1. The Netherlands and Turkey

3.2.2. Age Groups, Education Levels, and Income

3.2.3. Urban and Rural Areas

3.2.4. Gender

3.2.5. Summary

4. Discussion

4.1. On the Diversity of Topics Used

4.2. On the Complex Influence of Context

4.3. Limitations and Extendibility of the Research

- The research focused on individual consumers and their framing. The interactions between consumers, as well as the frames of and interactions with other stakeholders, though very relevant for follow-up research, have not been part of this research.

- In the research, the exact definitions of farming systems (e.g., in terms of exact area available per animal, measures taken, kind of feed used, grazing/non-grazing, etc.) were only taken into account when respondents mentioned these. To better connect research on the social acceptability of animal farming such as ours with scientific debates in the field of animal sciences, a deeper focus on the (non-)acceptability of different systems is required.

- The positivist-empirical validation of the objective truthfulness of pronounced arguments regarding certain ways of animal farming and meat consumption and the effects they have on human health, the animals involved, or the environment—which is indispensable in the dialogue on animal farming and meat consumption related matters—has not been part of the current research, that purely regarded the interpretation hereof by consumers. Moreover, the research was focused only on pronounced behaviours, and did not check if actually performed behaviours matched these.

- The research was limited to specific urban and rural areas in the Netherlands and Turkey.

- Quantitative confirmations of the influence of demographic contextual factors or demographic distribution of the use of specific clusters of reasoning and behaviour in framing have not been carried out within the timeframe of this study.

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Main Location | Link with Animal Farming | Gender | Age Group | Education Level | Occupation Type | Income Level (Able to Buy Desired Food?) | Pronounced Protein Consumption | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NL | Urban | No | M | 15–30 | Student | High school student, not yet working | Sufficient | Regular meat eater (Halal) |

| 2 | NL | Urban | No | M | 15–30 | Middle | Sales, youth work | Sufficient | Regular meat eater (Halal) |

| 3 | NL | Urban | Half | M | 30–50 | High | NGO office work | Sufficient | Compromise (only from ‘good sources’) |

| 4 | NL | Urban | No | M | 50+ | Low | Retired labourer | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 5 | NL | Urban | No | F | 15–30 | Low | Cleaning | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 6 | NL | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Journalism, writing | Sufficient | Compromise (less meat and only organic) |

| 7 | NL | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Horticulture | Minimal | Compromise (less meat and only from ‘good sources’) |

| 8 | NL | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Aquatic science | Sufficient | Compromise, mostly vegetarian |

| 9 | NL | Urban | No | F | 50+ | High | High school teaching | Sufficient | Compromise (just fish) |

| 10 | NL | Mixed | No | M | 15–30 | Middle | Intern, communications | Minimal | Regular meat eater/Compromise (less meat) |

| 11 | NL | Mixed | No | M | 15–30 | High | Volunteer coordinator | Sufficient | Vegetarian |

| 12 | NL | Mixed | Half | M | 50+ | Low | Jobless and homeless | None | Meat eater (no compromise) |

| 13 | NL | Mixed | No | M | 50+ | High | Lawyer | Sufficient | Vegetarian |

| 14 | NL | Mixed | No | F | 15–30 | High | Campaigner | Minimal | Vegetarian |

| 15 | NL | Mixed | No | F | 30–50 | High | Secretary | Sufficient | Compromise |

| 16 | NL | Mixed | Half | F | 30–50 | High | Computer engineer | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 17 | NL | Mixed | No | F | 30–50 | High | Food scientist | Sufficient | Regular meat eater/Compromise |

| 18 | NL | Mixed | No | F | 50+ | High | Creative therapist | Sufficient | Vegetarian/Compromise |

| 19 | NL | Rural | No | M | 30–50 | Middle | Mechanic and fireman | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 20 | NL | Rural | Yes | M | 30–50 | Middle | Organic farmer | Sufficient | Compromise (only organic) |

| 21 | NL | Rural | Yes | M | 50+ | Low | Dairy farmer | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 22 | NL | Rural | Yes | F | 50+ | Low | Farm worker | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 23 | NL | Rural | Yes | F | 50+ | Low | Farmer’s wife | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 24 | NL | Rural | No | F | 50+ | Middle | Forest conservationist | Sufficient | Vegetarian/Compromise (sometimes fish) |

| 25 | NL | Urban | Half | F | 30–50 | High | Researcher | Sufficient | Flexible vegan |

| 26 | TR | Urban | No | M | 15–30 | High | Student, film director | Sufficient | Compromise |

| 27 | TR | Urban | No | M | 15–30 | High | Doctor’s assistant | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 28 | TR | Urban | No | M | 30–50 | High | Captain | Sufficient | Compromise (less meat, only chicken and fish) |

| 29 | TR | Urban | Yes | M | 30–50 | Low | Butcher | Sufficient | Regular meat eater/compromise |

| 30 | TR | Urban | No | M | 30–50 | High | NGO campaigner and radio host | Sufficient | Vegetarian |

| 31 | TR | Urban | No | M | 50+ | High | Retired leather shop owner | Sufficient | Vegetarian/Compromise (only wild animals) |

| 32 | TR | Urban | No | F | 15–30 | Stud. | High school student | Sufficient | Compromise (trying out vegetarianism) |

| 33 | TR | Urban | No | F | 15–30 | High | Social scientist | Sufficient | Vegetarian, thinking about going back to eating meat |

| 34 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Tourism guide | Sufficient | Compromise (was vegetarian, eats meat only on the job) |

| 35 | TR | Urban | No | F | 50+ | Middle | Secretary | Sufficient | Compromise (no red meat, less meat) |

| 36 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | Middle | Restaurant co-owner | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 37 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Nurse | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 38 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Mathematics teacher | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 39 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | High | Translator | Sufficient | Vegetarian |

| 40 | TR | Urban | No | F | 30–50 | Low | Mother, photographer, stray animal welfare worker | Minimal | Vegetarian/Compromise (feeds meat to her animals, sometimes eats a bit) |

| 41 | TR | Urban | No | F | 50+ | High | Banker, hotel owner | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 42 | TR | Mixed | No | M | 15–30 | Low | Janitor | Minimal | Compromise |

| 43 | TR | Mixed | No | M | 15–30 | High | Food scientist, factory owner | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 44 | TR | Mixed | No | M | 50+ | Middle | Accountant | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 45 | TR | Mixed | No | M | 50+ | High | Imam | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 46 | TR | Mixed | No | F | 15–30 | High | Ecologist | Sufficient | Vegetarian/ Vegan |

| 47 | TR | Rural | Yes | M | 15–30 | Student | Farmer’s son | Minimal | Regular meat eater |

| 48 | TR | Rural | Yes | M | 30–50 | Middle | Horse therapist and sheep farmer | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 49 | TR | Rural | Yes | M | 30–50 | Low | Part-time farmer and restaurant manager | Sufficient | Regular meat eater |

| 50 | TR | Rural | Yes | F | 50+ | Low | Farmer | Very low | Regular meat eater |

References

- Te Velde, H.; Aarts, N.; van Woerkum, C. Dealing with ambivalence: Farmers’ and consumers’ perceptions of animal welfare in livestock breeding. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2002, 15, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B. Defining sustainability as a socio-cultural concept: Citizen panels visiting dairy farms in the Netherlands. Livest. Sci. 2008, 117, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, J.J. Farm animal welfare in the context of other society issues: Toward sustainable systems. Livest. Prod. Sci. 2001, 72, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, H.J.; van Trijp, H.C.M.; Aarts, N.M.C.; Ingenbleek, P.T.M. What is careful livestock farming? Substantiating the layered meaning of the term ‘careful’ and drawing implications for the stakeholder dialogue. NJAS: Wagening. J. Life Sci. 2013, 66, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schicktanz, S. Ethical considerations of the human-animal relationship under conditions of asymmetry and ambivalence. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2006, 19, 7–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, H.J.; Aarts, N.M.C.; Renes, R.J. Frames and ambivalence in context: An analysis of hands-on experts’ perception of the welfare of animals in traveling circuses in the Netherlands. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 26, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frewer, L.; Kole, A.; Kroon, S.M.A.V.; Lauwere, C. Consumer attitudes towards the development of animal-friendly husbandry systems. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2005, 18, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Oosting, S.J.; Bock, B.B. Elements of societal perception of farm animal welfare: A quantitative study in The Netherlands. Livest. Sci. 2006, 104, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbeke, W.; Vanpoucke, E.; Tuyttens, F. Do citizens and farmers interpret the concept of farm animal welfare differently? Livest. Sci. 2008, 116, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassen, L.; Sandøe, P.; Forkman, B. Happy pigs are dirty!—Conflicting perspectives on animal welfare. Livest. Sci. 2006, 103, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpell, J.A. Factors influencing human attitudes to animals and their welfare. Anim. Welf. 2004, 13, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, S.; Herzog, H.A. Personality and attitudes toward the treatment of animals. Soc. Anim. 1997, 5, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.C.; Makatouni, A. Consumer perception of organic food production and farm animal welfare. Br. Food J. 2002, 104, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Marrewijk, M.; Werre, M. Multiple levels of corporate sustainability. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doerfler, R.L.; Peters, K.J. The relativity of ethical issues in animal agriculture related to different cultures and production conditions. Livest. Sci. 2006, 103, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanhonacker, F.; Verbecke, W.; Poucke, E.V.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Segmentation based on consumers percieved importance and attitude toward farm animal welfare. Int. J. Sociol. 2007, 15, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Willetts, A. “Bacon sandwiches got the better of me” Meat-eating and vegetarianism in South-East London. In Food, Health, and Identity; Caplan, P., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1997; pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- Einwohner, R.L. Gender, class and social movement outcomes: Identity and effectiveness in two animal rights campaigns. Gend. Soc. 1999, 13, 56–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, H.A.; Lobao, L.M.; Sharp, J.S. Public concern with animal well-being: Place, social structural location, and individual experience. Rural Sociol. 2006, 71, 399–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothgerber, H.; Mican, F. Childhood pet ownership, attachment to pets, and subsequent meat avoidance. The mediating role of empathy toward animals. Appetite 2014, 79, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herzog, H. Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat. Why It’s so Hard to Think about Animals; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Joy, M. Why We Love Dogs, Eat Pigs, and Wear Cows: An Introduction to Carnism; Conari Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Werf, H.M.G.; Petit, J. Evaluation of the environmental impact of agriculture at the farm level: A comparison and analysis of 12 indicator-based methods. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 93, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, B.; van Eijk, O. Programma van Eisen van de Burger/Consument Met Betrekking tot de Melkveehouderij. Kracht van Koeien. whitetree.nl; Wageningen UR, Animal Sciences Group: Lelystad, The Netherlands, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bock, B.B.; van Huik, M.M. Animal welfare: The attitudes and behaviour of European pig farmers. Br. Food J. 2007, 109, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, G.; Henson, S. Consumer Concerns about Animal Welfare and the Impact on Food Choice: Final Report EU FAIR CT98-3678; The University of Reading: Reading, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan, R.; Gavinelli, A. The expanding role of animal welfare within EU legislation and beyond. Livest. Sci. 2006, 103, 303–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, F.H.; Goewie, E.A. In Het Belang van Het Dier: Over Het Welzijn van Dieren in de Veehouderij; van Gorcum; Assen and Rathenau Instituut: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations across Nations; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Şayan, Y.; Polat, M. Development of organic animal production in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 3rd SAFO Workshop, Falenty, Poland, 16–18 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Aerni, P. Editorial: Agriculture in Turkey—Structural change, sustainability and EU-compatibility. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2007, 6, 429–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grethe, H. The challenge of integrating EU and Turkish agricultural markets and policies. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2007, 6, 440–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akder, A.H. Policy formation in the process of implementing agricultural reform in Turkey. Int. J. Agric. Resour. Gov. Ecol. 2007, 6, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkish Grand National Assembly (TBMM). Hayvanları Koruma Kanunu (‘Animal Protection Law’). Available online: http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/kanunlar/k5199.html. in Mevzuat (‘Legislation’): http://www.tbmm.gov.tr/genser/giris.htm (accessed on 13 September 2012).

- Tanrivermis, H. Agricultural land use change and sustainable use of land resources in the mediterranean region of Turkey. J. Arid Environ. 2003, 54, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, H.J. On the Welfare of Farmed Animals in the Republic of Turkey: The Meat Chicken Case. MSc Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, October 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nijland, H.J. Het Houden en Doden van Varkens Voor Voedsel Door de Mens: Acceptabel? Ethische en Andere Argumenten in Kaart Gebracht. MSc Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands, September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaard, B.K.; Bock, B.B.; Oosting, S.J.; Wiskerke, J.S.C.; Zijpp, A.J. Social Acceptance of Dairy Farming: The Ambivalence Between the Two Faces of Modernity. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2010, 24, 259–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- FAO Country Profile: Turkey. Available online: http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index/en/?iso3=TUR (accessed on 27 March 2016).

- FAO Country Profile: The Netherlands. Available online: http://www.fao.org/countryprofiles/index/en/?iso3=nld (accessed on 27 March 2016).

- Fraser, D. Toward a global perspective on farm animal welfare. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 113, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, W.B.; Littlejohn, S.W. Moral Conflict, When Social Worlds Collide; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, N.M.C.; Van Woerkum, C. Frame construction in interaction. In Multi-Organisational Partnerships, Alliances and Networks. Engagement, Proceedings of the 12th MOPAN International Conference, Wales, UK, 22–24 June 2005; Short Run Press: Exeter, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Te Molder, H. Discursive psychology. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication; Donsbach, W., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK; Malden, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Te Molder, H. Discourse communities as catalysts for science and technology communication. In Citizen Voices. Performing Public Participation in Science and Environment Communication; Phillips, L., Carvalho, A., Doyle, J., Eds.; Intellect/The University of Chicago Press: Bristol, UK; Chicago, IL, USA, 2012; pp. 97–118. [Google Scholar]

- Lindenberg, S. Why framing should be all about the impact of goals on cognitions and evaluations. In Hartmut Essers Erklärende Soziologie; Hill, P., Kalter, F., Kroneberg, C., Schnell, R., Eds.; Campus: Frankfurt, Germany, 2009; pp. 53–79. [Google Scholar]

- Entman, R.M. Framing: Towards clarification of a fractured paradigm. J. Commun. 1993, 43, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tannen, D.; Wallat, C. Interactive Frames and Knowledge Schemas in Interaction : Examples from a Medical Examination/Interview. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 50, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, A.; Gray, B.; Putnam, L.; Lewicki, R.; Aarts, N.; Bouwen, R.; Van Woerkum, C. Disentangling approaches to framing in conflict and negotiation research: A meta-paradigmatic perspective. Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 155–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.H.G. Analyzing Framing Processes in Conflicts and Communication by Means of Logical Argument Mapping. In Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication; Donohue, W., Rogan, R., Kaufman, S., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 136–166. [Google Scholar]

- Donohue, W.A.; Rogan, R.G.; Kaufman, S. Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A.; Kahneman, D. The Framing of Decisions and the Psychology of Choice. Science 1981, 211, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olekalns, M.; Smith, P.L. Mindsets: Sensemaking and Transition in Negotiation. In Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication; Donohue, W., Rogan, R., Kaufman, S., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Aarts, N.; Lieshout, M.; Van Woerkum, C. Competing claims in public space: The construction of frames in different relational contexts. In Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication; Donohue, W., Rogan, R., Kaufman, S., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 234–254. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D. Organizational change as shifting conversations. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 1995, 12, 480–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kickert, W.J.M.; Klijn, E.J.; Koppenjan, J.F.M. (Eds.) Managing Complex Networks. Strategies for the Public Sector; Sage Publications, Inc.: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rein, M.; Schön, D.A. Frame-Reflective Policy Discourse. Beleidsanalyse 1986, 15, 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bartunek, J.M. The dynamics of personal and organizational reframing. In Paradox and Transformation: Toward a Theory of Change in Organization and Management; Quinn, R.E., Cameron, K.S., Eds.; Ballinger: Cambridge, UK, 1988; pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- De Carlo, L. About change processes in intractable negotiations: From frames to ambivalence, paradox and creativity. In Proceedings of the IACM 18th Annual Conference, Seville, Spain, 12–15 June 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale, P.J. Dynamics of Frame Change: The Remarkable Lightness of Frames, and Sticky Frames. In Framing Matters: Perspectives on Negotiation Research and Practice in Communication; Donohue, W.A., Rogan, R.C., Kaufman, S., Eds.; Peter Lang: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 268–275. [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer, J.E.; Maio, G.R.; Pakizeh, A. Feeling torn when everything seems right: Semantic incongruence causes felt ambivalence. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2013, 39, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherner, K.R. Psychological Models of Emotion. In The Neuropsychology of Emotion; Borod, J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 137–162. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, R.W.; Hendriks, M.; Aarts, H. Smells like clean spirit: Noncsious effects of scent on cognition and behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2005, 16, 689–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, R.W. Fact and Opinion in Defamation: Recognizing the Formative Power of Context. Fordham Law Rev. 1990, 58, 761. [Google Scholar]

- Midgley, M. Why There Is Trouble Over Knowledge. In Can’t We Make Moral Judgements? Midgley, M., Ed.; Palgrave Macmillan US: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.D.; Ford, L.W.; McNamara, R.T. Resistance and the background conversations of change. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2002, 15, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, M. “The Four-Leggeds. The Two-Leggeds, and the Wingeds”: An Overview of Society and Animals, 1, 1. Soc. Anim. 1993, 1, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jonge, F.H.; Spruijt, B.M. Animal welfare, scientific uncertainty and public debate. In The Human-Animal Relationship: Forever and a Day; de Jonge, F.H., van den Bos, R., Eds.; Uitgeverij van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 164–180. [Google Scholar]

- Bormann, E.G. Symbolic convergence theory: A communication formulation. J. Commun. 1985, 35, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaffield, S. Frames of Reference: A Metaphor for Analyzing and Interpreting Attitudes of Environmental Policy Makers and Policy Influencers. Environ. Manag. 1998, 22, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Silverman, D. Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball Sampling: Problems and Techniques of Chain Referral Sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, G.A. Naturalistic inquiry and the saturation concept: A research note. Qual. Res. 2008, 8, 137–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, A. Antropologische Perspectieven; Dick Coutinho: Muiderberg, The Netherlands, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Flyvbjerg, B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual. Inq. 2006, 12, 219–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenz, P.S. Environmental Justice; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron, G. Rapid appraisal methods for the assessment, design, and evaluation of food security. Int. Food Policy Res. Inst. 1999, 6, 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, T.J.; Dethloff, C.; Westberg, S.J. Advancements in laddering. In Understanding Consumer Decision Making: The Means-end Approach to Marketing and Advertising Strategy; Reynolds, T.J., Olson, J.C., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Mateson, J.L. Computer-Aided Qualitative Data Analysis Software: General Issues for Family Therapy Researchers. In Research Methods in Family Therapy; Sprenkle, D.H., Piercy, F.P., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2005; pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar]

- Schurgers, E.; Capiot, R. Welke eter ben jij? Belang van Limburg, 30 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vegetarërsbond. Factsheet 1: Consumptiecijfers en aantallen vegetariërs. Available online: https://www.vegetariers.nl/bewust/veelgestelde-vragen/factsheet-consumptiecijfers-en-aantallen-vegetariers- (accessed on 20 August 2015).

- Diyetisyen Dunyası. Available online: http://www.diyetisyendunyasi.com/guncel-haberler/200-diyetisyen-yesim-ozcan-turkiyedeki-vejetaryen-sayisi (accessed on 20 August 2015).

- Hurriyet Daily News. Available online: http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/high-meat-prices-planned-imports-ruffle-feathers-in-turkey-86850 (accessed on 15 August 2015).

- Et ve Süt Kurumu. Available online: http://www.esk.gov.tr/tr/12197/Satis-Fiyatlari (accessed on 21 January 2017).

- NUMBEO. Available online: http://www.numbeo.com/food-prices/country_result.jsp?country=Netherlands (accessed on 21 January 2017).

- Popper, K. The Logic of Scientific Discovery; Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable; Random House: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.L. Sex differences in empathy and related behaviors. Psychol. Bull. 1977, 84, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisenberg, N.; Lennon, R. Sex differences in empathy and related capacities. Psychol. Bull. 1983, 94, 100–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.J.K.; Hodges, S.D. Gender differences, motivation, and empathic accuracy: When it pays to understand. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 720–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levenson, M. Gender and wisdom: The roles of compassion and moral development. Res. Hum. Dev. 2009, 6, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoe, E.E.A.; Cumberland, A.; Eisenberg, N.; Hansen, K.; Perry, J. The influences of sex and gender-role identity on moral cognition and prosocial personality traits. Sex Roles 2002, 46, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijland, H.J. De facetten van zorgvuldigheid. In Over Zorgvuldige Veehouderij: Veel Instrumenten, één Concert; Eijsackers, H., Scholten, M., van Arendonk, J., Backus, G., Bianchi, A., Gremmen, B., Hermans, T., van Ittersum, M., Jochemsen, H., Oude Lansink, A., et al., Eds.; Wageningen UR.: Wageningen, The Natherlands, 2010; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Teasdale, J.D.; Barnard, P.J. Affect, Cognition and Change: Remodelling Depressive Thought; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, M.L. Empathy and Moral Development. Development (I.); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman, P. Moods, Emotions, and Traits. In The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions; Ekman, P., Davidson, R., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1994; pp. 56–58. [Google Scholar]

- Esbjörn-Hargens, S. An Overview of Integral Theory: An All-Inclusive Framework for the 21st Century. Resource Paper No. 1; Integral Institute: Louisville, CO, USA, 2009; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, H.J.M. The construction and reconstruction of a dialogical self. J. Constr. Psychol. 2003, 16, 89–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleeson, W. Moving Personality beyond the Person-Situation Debate: The Challenge and the Opportunity of Within-Person Variability. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2004, 13, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, N.; Jephcott, E. The Civilizing Process; Pantheon Books: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Goudsblom, J. Balans van de Sociologie; Uitgeverij Het Spectrum: Utrecht, The Netherlands; Antwerpen, Belgium, 1983. [Google Scholar]

| me (placed in the centre of the circles) | staple (placed outside the circles) | someone on the other side of the world | my pet (if existent) |

| tomato | sheep | lamb | grasshopper |

| fish | a farmer | rabbit | broiler chicken |

| cow | dolphin | mosquito | wild chicken |

| pig | Swan | snake | my best friend |

| dog | carrot | laying hen | elephant |

| frog | flour worm | horse | cat |

| Red meat | Poultry | Fish | Eggs | Dairy | Honey | Grains | Roots | Vegetables | Fruits | Nuts and seeds | Beans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omnivore Eats animals, animal products, as well as plants | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Carnivore Eats mostly meat | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Vegetarian Refrains from eating meat or fish, does eat eggs and dairy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Vegan Refrains from eating and using any animal products | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lacto vegetarian Refrains from eating meat, fish and eggs, does eat dairy | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Ovo vegetarian Refrains from eating meat and dairy, does eat eggs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Pescotarian Refrains from meat and poultry, does eat fish | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Pollotarian Refrains from red meat and fish, does eat poultry | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Fruitarian Refrains from eating “living” plants (roots), does eat their products (fruits, nuts, beans) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Flexitarian Consciously eats less meat | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nijland, H.J.; Aarts, N.; Van Woerkum, C.M.J. Exploring the Framing of Animal Farming and Meat Consumption: On the Diversity of Topics Used and Qualitative Patterns in Selected Demographic Contexts. Animals 2018, 8, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8020017

Nijland HJ, Aarts N, Van Woerkum CMJ. Exploring the Framing of Animal Farming and Meat Consumption: On the Diversity of Topics Used and Qualitative Patterns in Selected Demographic Contexts. Animals. 2018; 8(2):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8020017

Chicago/Turabian StyleNijland, Hanneke J., Noelle Aarts, and Cees M. J. Van Woerkum. 2018. "Exploring the Framing of Animal Farming and Meat Consumption: On the Diversity of Topics Used and Qualitative Patterns in Selected Demographic Contexts" Animals 8, no. 2: 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8020017

APA StyleNijland, H. J., Aarts, N., & Van Woerkum, C. M. J. (2018). Exploring the Framing of Animal Farming and Meat Consumption: On the Diversity of Topics Used and Qualitative Patterns in Selected Demographic Contexts. Animals, 8(2), 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8020017