1. Introduction

All actions have reactions, but some moments in history are defining. On 2 July 2015, the killing of a 13-year old male lion, Panthera Leo (nicknamed “Cecil” by the researchers in our team who had tracked his movements by satellite since 2009) certainly prompted a reaction, and we argue that, in terms of attracting global attention, it was the largest reaction in the history of wildlife conservation. As a moment, measured by media coverage and public engagement, it was immense. But was it a defining moment, in the sense of changing, or at least offering an opportunity to change, history? Will the Cecil Moment presage the Cecil Movement?

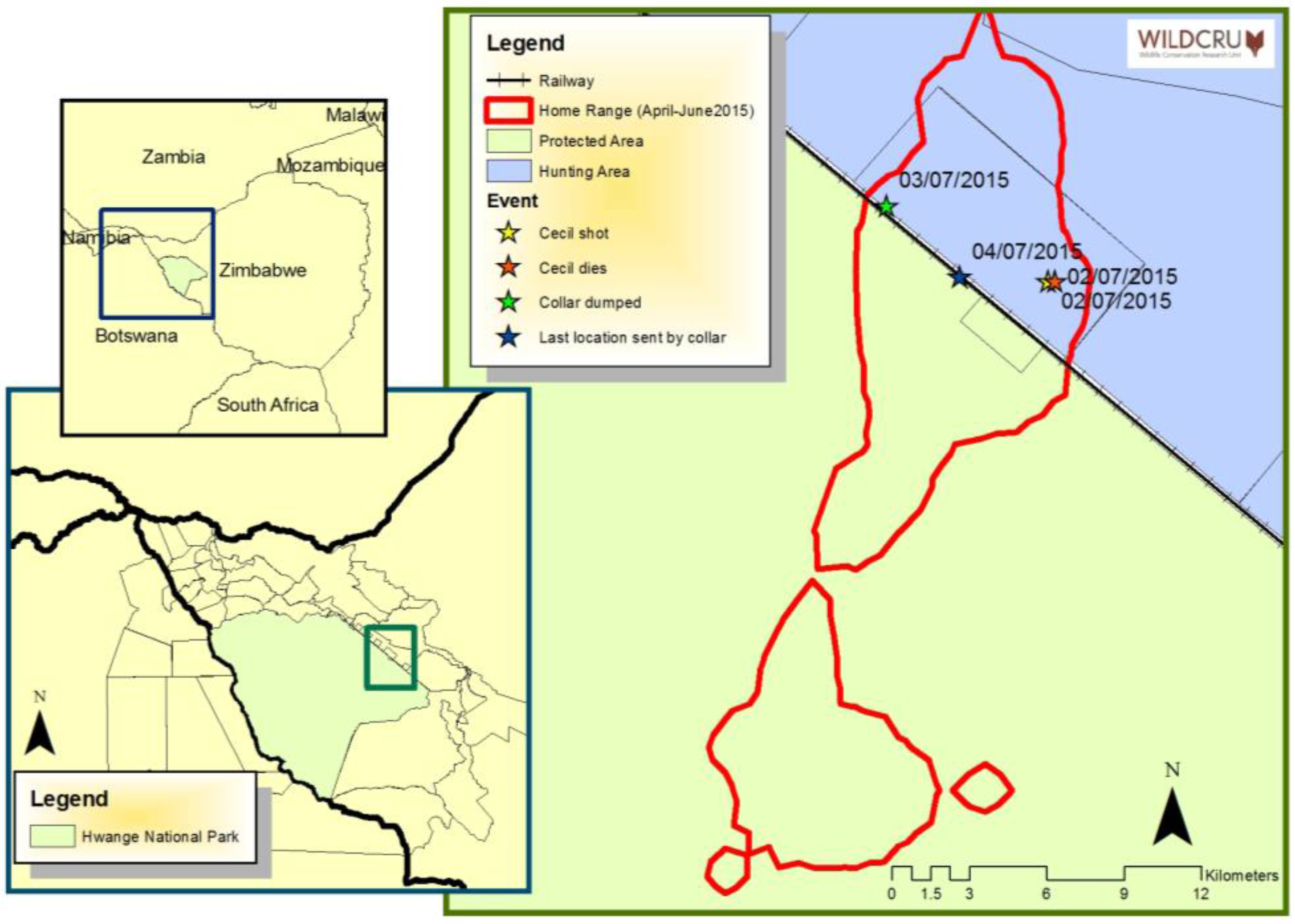

As a step towards considering that larger question, here we document and quantify the unfolding story. As background, in 1999, two of us (David W. Macdonald and Andrew J. Loveridge), researchers at Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU) established a study of lions in Hwange National Park, Zimbabwe, and parts of the surrounding Kavango Zambezi (KAZA) landscape. The motivation was to provide evidence to underpin the conservation of the lions populating this region while advancing the well-being of the human communities living alongside them. Following an early focus on the impact of trophy hunting around Hwange on lions, our evidence resulted in a

ca. 90% reduction of legally hunted lions as licensed by Zimbabwe’s National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority [

1,

2]. From 1999–2015, approximately 65 lions were hunted on the land surrounding the Protected Area, 45 of them were equipped with tracking devices. None of these deaths attracted much attention from the world’s media, including the two other satellite-collared lions, both also bearing nicknames, killed by trophy hunters in 2015. Similarly, the illegal shooting of a radio-collared cheetah nicknamed “Legolas” in October in Botswana scarcely gained a foothold in the press [

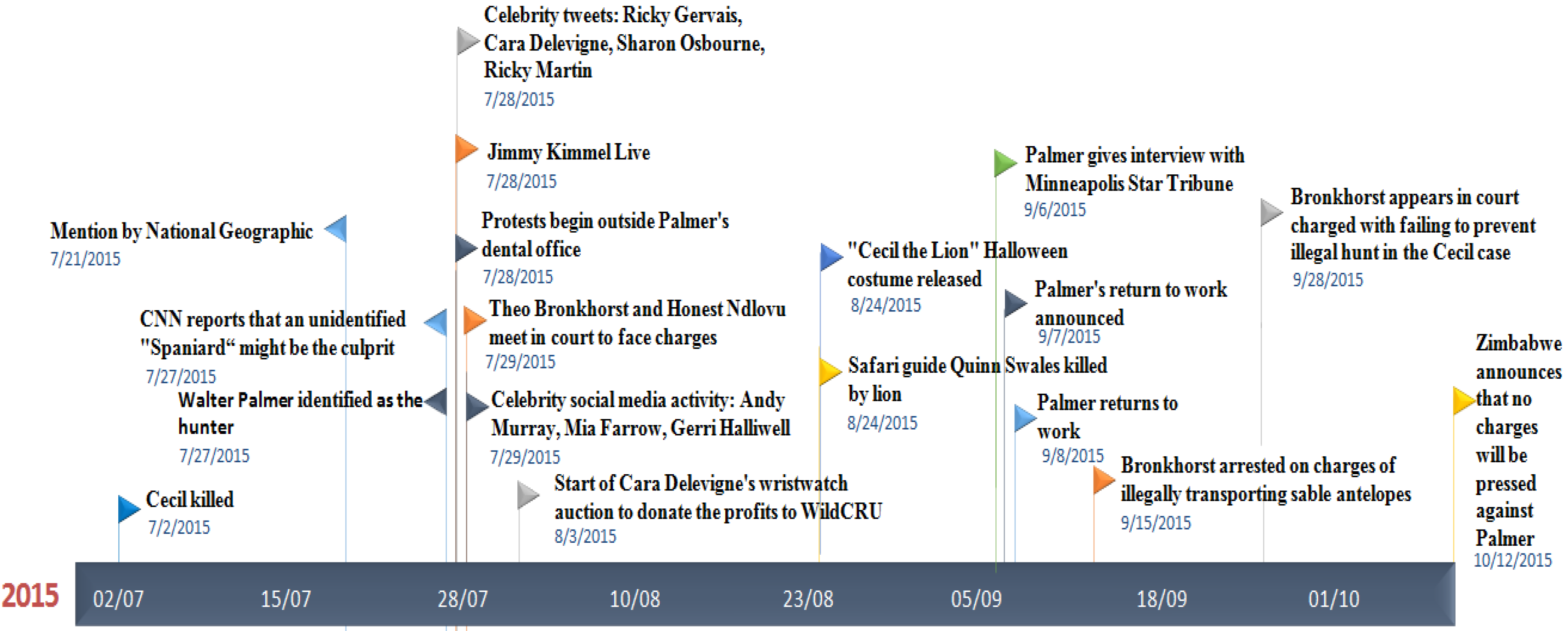

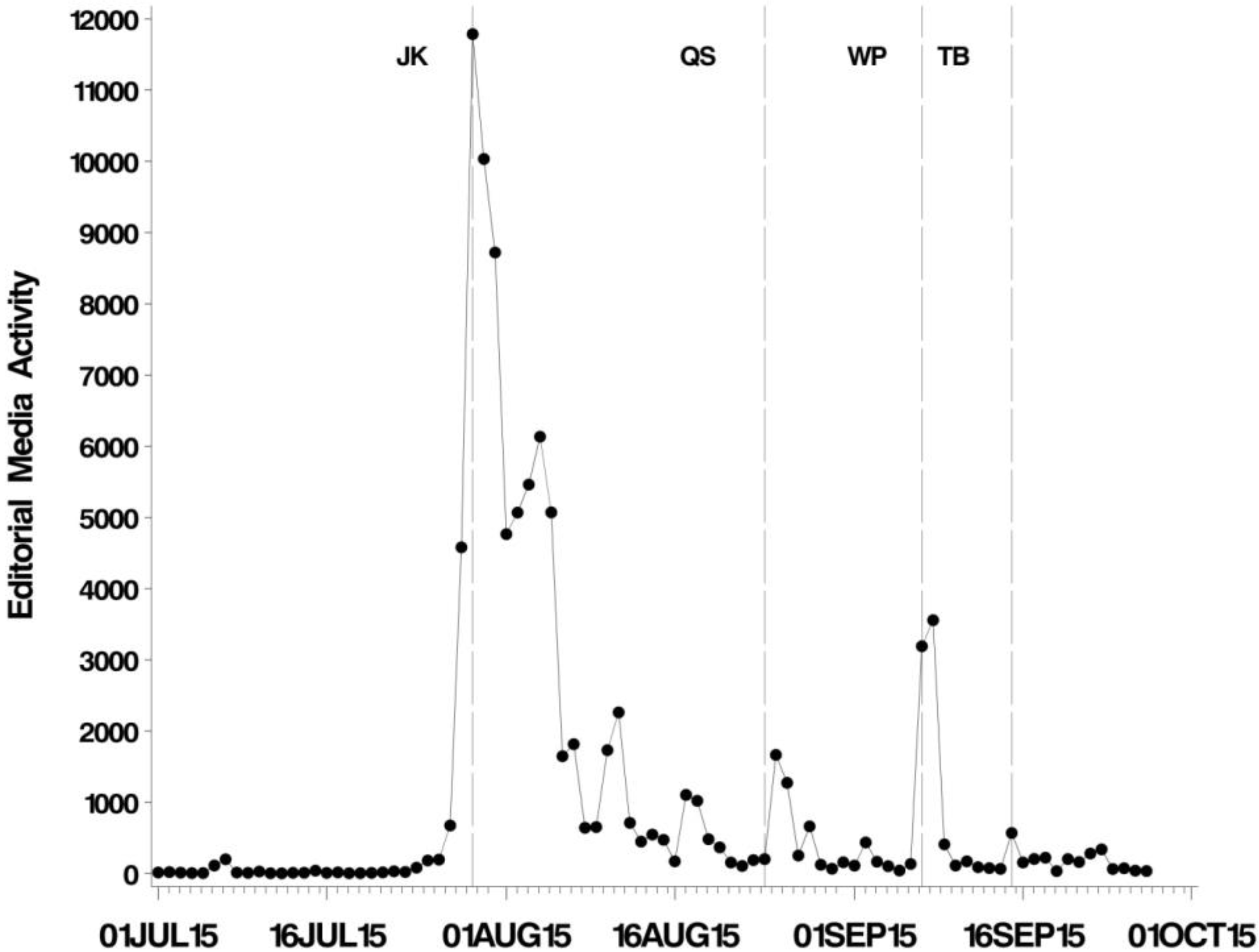

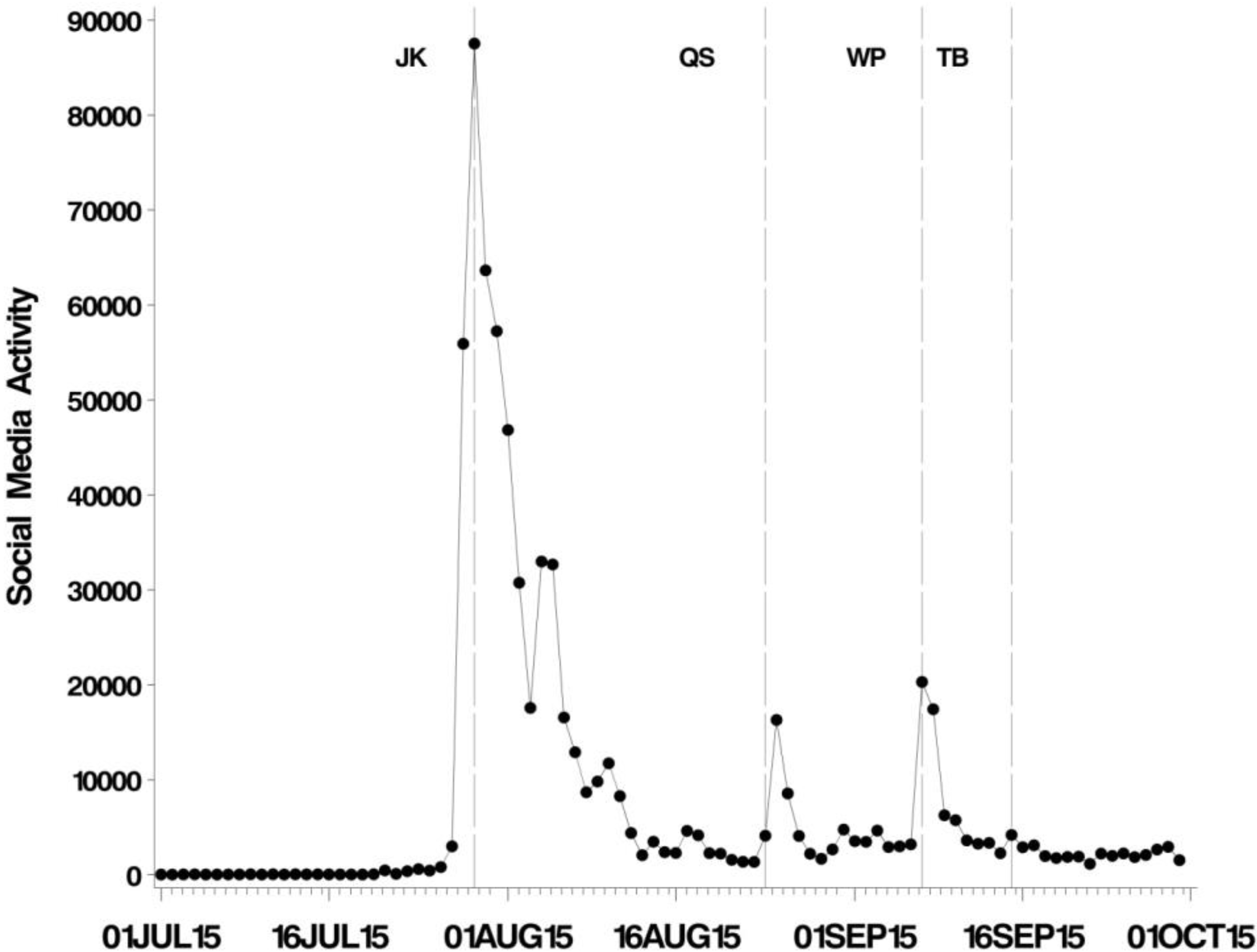

3]. In considering why Cecil attracted such a volume of interest, we report the chronology of events. The salient facts are that Cecil, equipped with a satellite tracking collar, was reported (incorrectly) to have been lured by bait out of the park, wounded by the bowhunter (on an allegedly illegal hunt) who finally despatched the lion the next day. Alerted to this, the Zimbabwean National Parks and Wildlife Management Authority initiated an investigation of the trophy hunter, the professional hunter who accompanied him and the land-owner. Media coverage of this was picked up by U.S. talk show host, Jimmy Kimmel, who, on 28 July, broadcast an impassioned criticism of the episode. With the WildCRU web address on the screen, he said “show the world not all Americans are like this jackhole” (a reference to the dentist), telling his television audience about WildCRU’s work on this lion and urging them to support it by visiting our website. In the following h an estimated 4.4 million people did so, causing the collapse of both WildCRU’s and Oxford University’s websites. It is noteworthy, however, that media coverage of the story was showing a steep upward trend before the Kimmel monologue. In subsequent days the story spread explosively on both traditional and social media. For example, on 30 July there were some 900 articles worldwide about the WildCRU in 24 h.

Both the traditional editorial media, and, more recently, the social media, can contribute to social change and have been implicated in political upheavals [

4] such as “the Arab Spring” [

5]. Against this background, we seek to characterise the contagion of media reporting of the Cecil episode in both time, from day to day, and space, as it spread around the world. Our purpose is to document the episode both qualitatively and quantitatively. This is not only because it was widely felt to be unique in the history of conservation, but principally to begin the ambitious process of evaluating whether the global interest in the killing of this lion diagnoses a moment in history at which a wide citizenry revealed their disposition to value, and thus to conserve, wildlife more broadly. If so, this is important in the politics of conservation and the wider environment, and raises the possibility that the Cecil Moment might become the Cecil Movement.

4. Discussion

The attention given to the Cecil story was immense, reaching 99,000 reports per day in the social and editorial media combined (nearly 1000 per day mentioning WildCRU). Strong feelings were clear in the content of social media postings. And in the non-digital world, protests took place outside Mr. Palmer’s dental surgery. Those protests started before Jimmy Kimmel delivered his monologue. The patterns are closely similar between the editorial and social media, and in both cases the huge peak of interest declines over the course of about one month. While thereafter the daily scores seem small in comparison to the peak, they remain large by comparison with most conservation stories. At the least, the Cecil Moment is a prolonged one.

The editorial media peaked in synchrony across the world’s regions but after the peak there were differences. Media saturation was highest in North America, the home of the trophy hunter dentist, and where the Jimmy Kimmel appealed to patriotism. The Cecil story showed the most dramatic behaviour in this region. In contrast, it took longer before Africa experienced its largest increase in hits from one day to the next, and had a more sustained interest level after the peak, with fewer spikes defined as events. Thus, the coverage of the Cecil story seems to have been more moderate and more sustained in Africa compared to other world regions.

The coverage in both editorial and social media was similar. The peaks occurred at the same time, and there were no obvious differences in the trajectories. This does not support assumptions that viral phenomena of this nature are primarily driven by social media (we use the expression “viral” in the same sense as Berger and Milkman 2012) [

11]. Also when comparing three of the largest social media channels to each other the synchrony is striking. There are no clear forerunners within the social media sphere or between editorial and social media, suggesting instead a highly interconnected media universe: this is the reality with which conservationists must interact, and involved Cecil’s story spreading synchronously across media channels, and geographically across the globe, over the span of about two days.

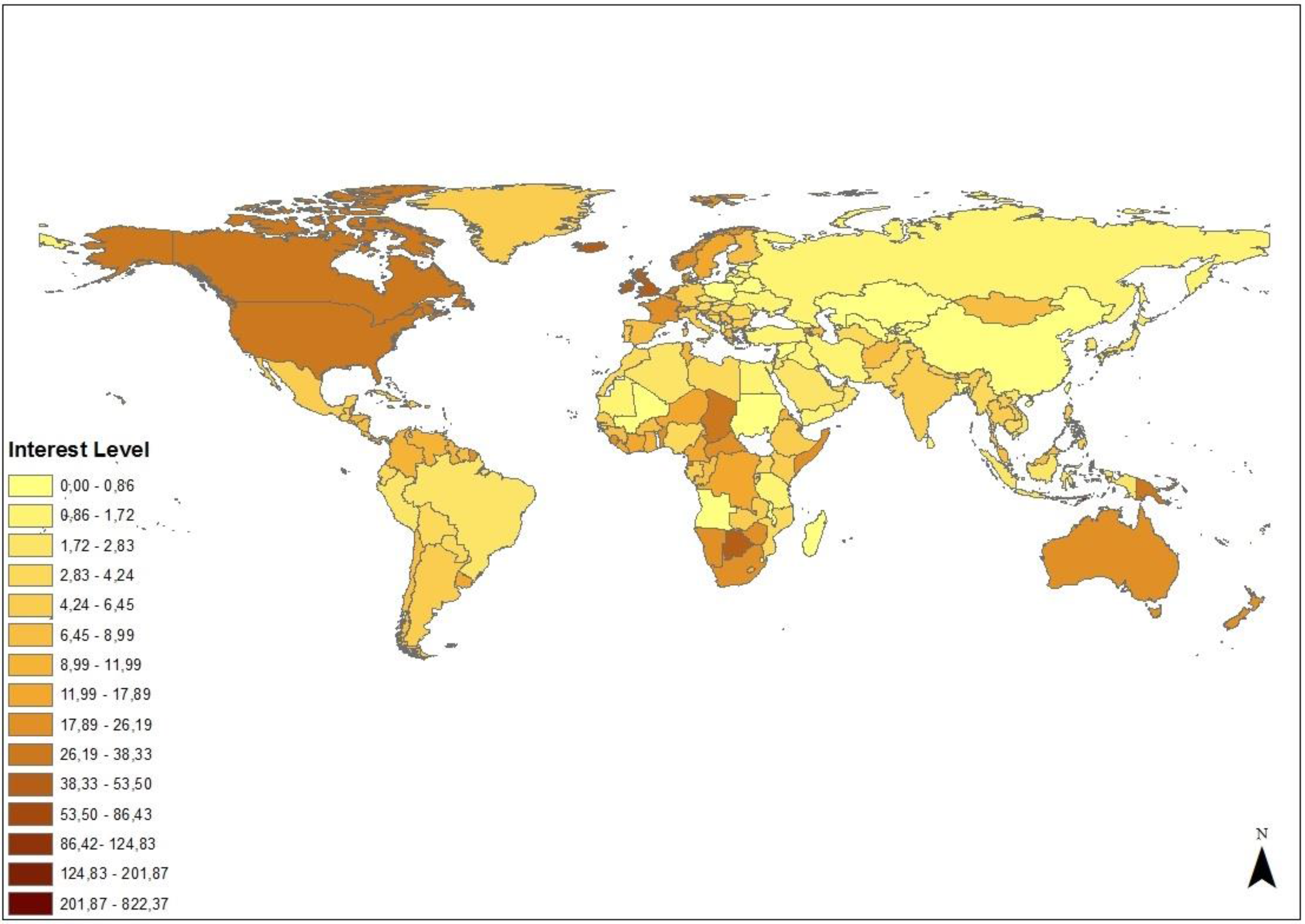

The distribution of social media interest across the globe (

Figure 5) indicates that interest in the Cecil case was not limited to wealthier countries. There is a high level of engagement across certain sub-Saharan countries and the interest levels in large parts of South and Central America are comparable to those in Europe. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that media saturation in each country was unrelated to infant mortality (data for 2011–2015 obtained from The World Bank [

12]) which is an indicator of population health [

13], or to the indices of governance, economic success or conservation policy derived by Dickman

et al. [

14] (|r| < 0.15,

p > 0.07). This has to be interpreted in light of the fact that a significant portion of the population in many of these countries will have limited access to internet or printed media, so the media saturation/interest levels will be determined by the segments of society that do.

We cannot say exactly which aspect of the case was attracting attention at a given time in a given place or, for example, whether it was motivated by distaste for trophy hunting or concern for either animal welfare or conservation (we are mindful that further content analysis, which we plan, could reveal much about the motivations of underlying the public and media responses). Hits may also be generated by people expressing opposing views or denouncing the media attention given to Cecil’s death (e.g., [

15]), so we can only document the degree to which the editorial media and social media users in a country engage in coverage and debate about Cecil’s death.

Why did this particular story touch a wide public so forcefully when such trophy hunting events are far from unusual? The lion in question was majestic, rather well-studied, bore an English nickname (more memorable than its data code of MAGM1); it was allegedly lured to its death (although it routinely left the park of its own volition), was wounded with an arrow and endured a lingering death, was killed in apparently dubious circumstances, by a client who was identifiable (as opposed to amorphous villains such as polluting industries in the case of climate change), wealthy, white, male and American and who, to judge by media reports, had previously been associated with problematic hunting episodes. Each of these elements might seem problematic and, to some, not just reprehensibly illegal but morally deplorable [

16], but neither separately nor in many partial combinations are they unique. It seems plausible then that it is their combination, certainly unusually and perhaps uniquely, that led to the viral explosion. It might also be the case that the episode was so remote from the daily experience of many people, that they felt able to make a straightforward condemnation of it, with no feeling of related guilt about their own behavior [

17]. Studies of the forces that shape viral episodes online have found that physiological arousal is important [

11]. Negative emotions increase transmission rates – but anger is a more potent stimulant for sharing posts than is sadness because it is accompanied by greater arousal. It is clear from the most cursory exploration of the social media content that visible anger was a very common thread running through posts concerning Cecil. Something else that may have contributed to the virality of the episode was its breadth of appeal. Surprise and anger were not confined to any geographic region. There is some evidence that, while cascades of “sharing” on social media are difficult to predict, breadth in the sense of the number of ‘roots’ a re-sharing tree has is a good predictor of large cascades [

18]. We might compare the Cecil episode to that which surrounded a man-eating tiger in India [

19]. A decision to relocate the tiger from a National Park caused very different reactions across Indian society, with strong feelings and anger on both sides of the debate, and wide coverage on social media. However, the debate attracted little coverage outside India. There is some evidence that negative stories have lower persistence than positive ones [

20]; the trajectory of the ‘Cecil’ story coverage fits more closely that of the ‘bad news’ than ‘good news’ stories studied by those authors.

Although we have not quantified the content of the media coverage or the opinions expressed in the social media, we have gained impressions from these, and also from direct correspondence to our Unit, about why the hunt provoked the anger that it did. For example, from the many emails and letters, we inferred that people were more concerned that the hunt was for a trophy rather than for meat, that the quarry was a carnivore rather than an ungulate, and that it was a large species rather than a small one. There was overwhelming distaste for trophy hunting of a big cat, and a sense that this approbation was fuelled by moral indignation at the act, generally articulated more in terms of a concern for animal welfare (including the family factor of concern for the surviving pride members) than for conservation. These motivations, and particularly the perceived framing of distaste in terms of animal welfare, and possible conflation between this topic and conservation, are subjects that merit further research. It was clear from many interviewers and correspondents that there was widespread ignorance that trophy hunting still occurs widely across Africa, or that much more land is in fact set aside for trophy hunting than for National Parks, or that some mainstream conservationists believe that properly managed trophy hunting can contribute to conservation [

21], even if it is uncertain how often it does so [

22].

Indeed, the suggestion that trophy hunting of lions could be a tool for conservation (a proposition that requires urgent critical analysis), through giving commercial value to animals that in some parts of Africa would otherwise be considered as pests and not tolerated, was seemingly widely regarded as morally despicable. This raises interesting and urgent societal (and ethical) issues: not just in the wider context of wildlife conservation, but specifically in the case of lions and other big predators. The revenues of both trophy hunting and photo-tourism are widely discussed, and often said to be not only engines for conservation and incentives for maintaining wildlife habitat instead of conversion to alternative land-uses, but also a driver for the development of poor communities. In the case of lion economics, these claims merit more careful analysis than has hitherto been the case. Our team has identified, and is now tackling, two critical questions: to what extent would the cessation of trophy hunting for lions cause a reduction, or even collapse, of the financial support that trophy hunting makes to wildlife conservation, and thus what sum of money would be required to make good the loss of revenue to conservation should trophy hunting of lions cease? It is urgent to quantify this figure insofar as an alternative source for it would have to be found in the event that trophy hunting of lions ceased. Insofar as global opinion might create circumstances which made lion trophy hunting unviable (or banned it outright), and insofar as such hunting might indeed currently contribute to financing conservation of lions and beyond, it would seem prudent to plan for a journey towards that outcome, rather than to jump precipitously to it. That said, our sense of the global interest in Cecil was that it suggested a prevailing moral standpoint whereby ethical consideration rendered it inappropriate to consider economic ones. We sensed that the prevailing opinion was that ethics trumped finance in this context, and that arguing against that was perceived as morally equivalent to, for example, justifying slavery on the basis of its revenue generating capacity. Conservationists seeking the best consequentialist compromise, then, were likely to be judged harshly by history. If this is indeed the prevalent global mood, and insofar as trophy hunting does indeed give lions a value that prevents their eradication, it is obviously urgent to find an alternative means of encouraging (presumably paying) people to tolerate them In addition to media attention, which costs the individuals involved almost nothing, by 25 September 2015, WildCRU had received $1.06 million dollars from 13,335 donors (the majority from North America). We can assume that these were a persistent subset of the 4.4 million visitors to the WildCRU website on the night of the Jimmel Kimmel plea that were thwarted in their attempts to donate. If conservationists are able to harness this enthusiasm and action then perhaps there is hope that global society could pay for global commons and secure the protection of lions in Africa. Indeed, the particular charismatic appeal of big cats [

23], combined with the unique response to Cecil, in the face of the species’ rapidly deteriorating status [

24], suggest to us that lions might have a unique capacity to galvanize populist funding from the public to foster their own conservation and thereby to act as ambassadors for wildlife more widely.

The urgency to find means to make good any loss of funds for lion conservation that might follow from a reduction or cessation in trophy hunting is enhanced by the radical shifts in related policy that have already been prompted by Cecil’s death. For example the banning of transporting lion trophies from Africa to Europe and America by several airlines [

25] may precipitate, very quickly, a state change in the viability of lion trophy hunting. Similarly, the requirement of the USFWS amendments to the Endangered Species Act, requiring nations to demonstrate that lion hunting is managed in ways that give a net advantage to lion conservation may set a bar that cannot easily be jumped, and it would not be surprising if similar strictures were adopted by the European Union [

26]. In short, insofar as lion conservation is affected by trophy hunting, the conservation community would be wise to prepare for rapid change. This is a moment that offers an opportunity for radical thinking about the conservation of lions, and indeed of wildlife more generally: It raises a deep question that is ultimately about how, in the 21st Century, the human enterprise is to co-exist with nature.The answers will lie beyond conservation biology and, while fostering the very best that existing approaches can, and may yet offer, will require innovative thinkers to stand back, seek new strategic ideas and ask: can the mold be broken? The answers are likely to lie at the interface of cutting edge economics, development, governance, regulation and, ultimately, politics. In particular, does the global interest in lion conservation unleashed by the killing of this lion create a moment, the Cecil Moment, that can be grasped to enable conservationists to lead wider society in stopping, and indeed reversing, the decline in lions? Maybe there is no such opportunity, given the pressures of a burgeoning human population set to double in Africa by 2050 [

27]; but, there is a chance that the opportunity does exist and, fearful of squandering it, now is the moment to take a fresh look at high level strategic thinking for lion conservation.