Impact of the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster on the Endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Rice Fields of Mabi Town, Kurashiki City, Western Japan: Changes in Population Structure over Five Years

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

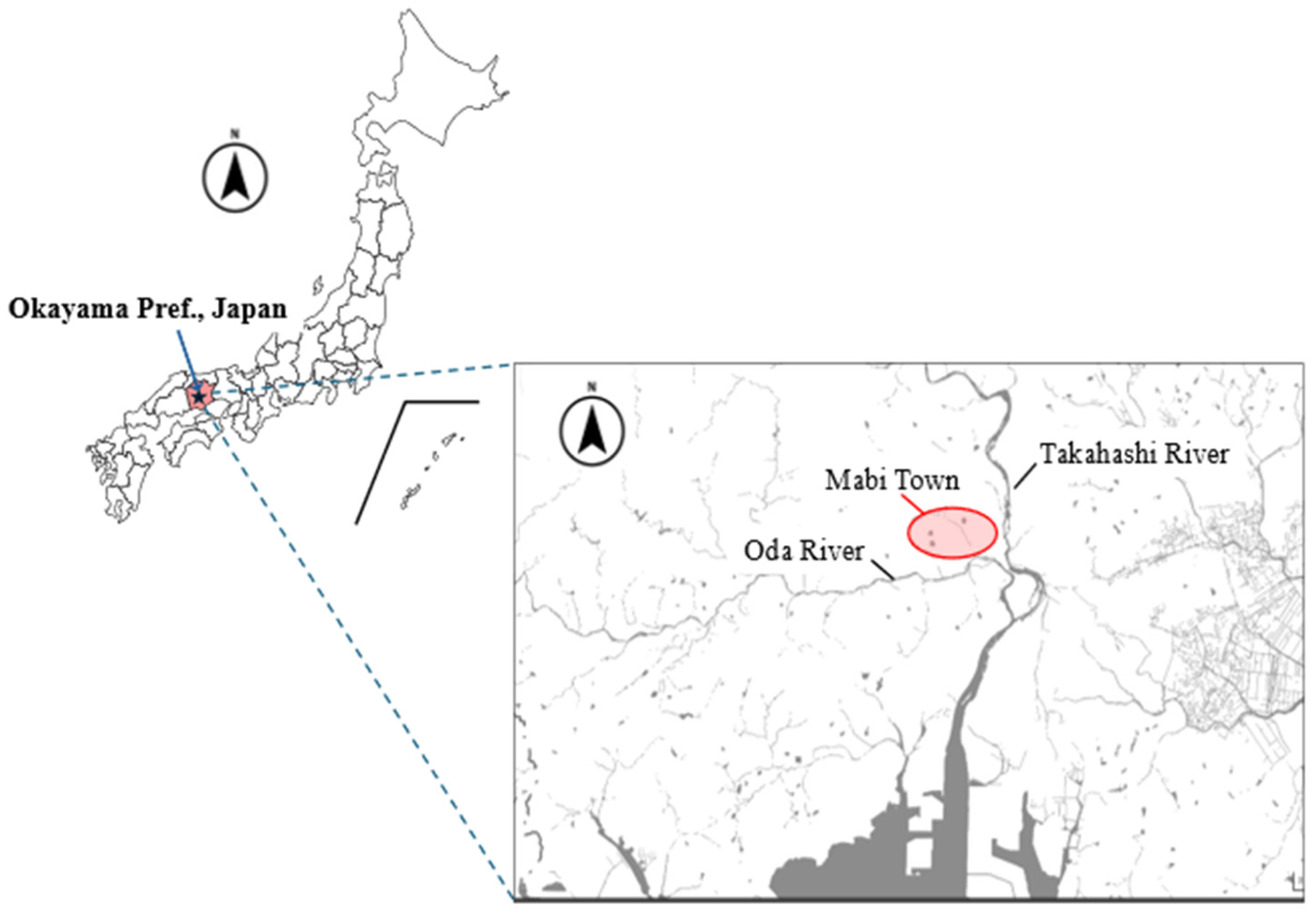

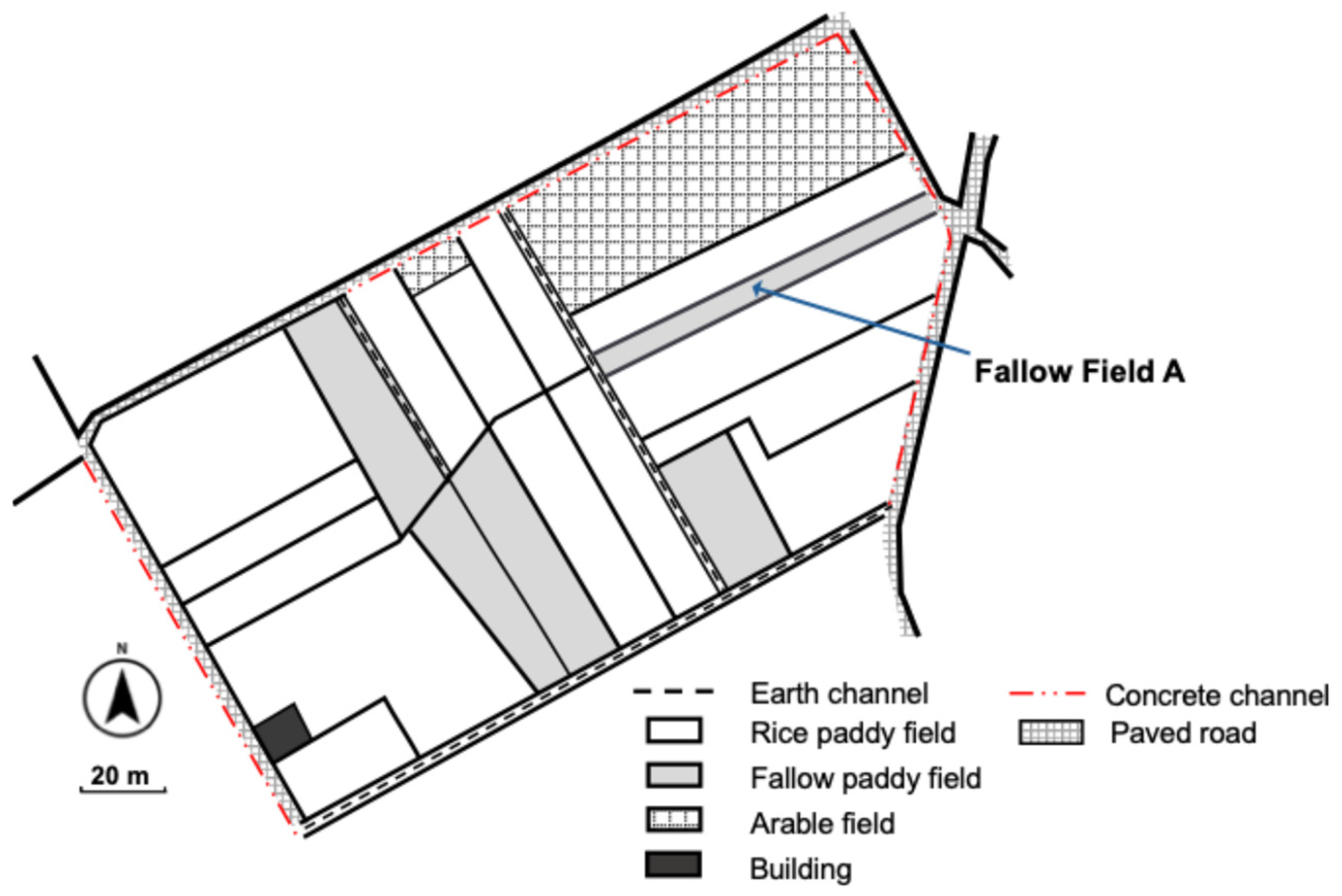

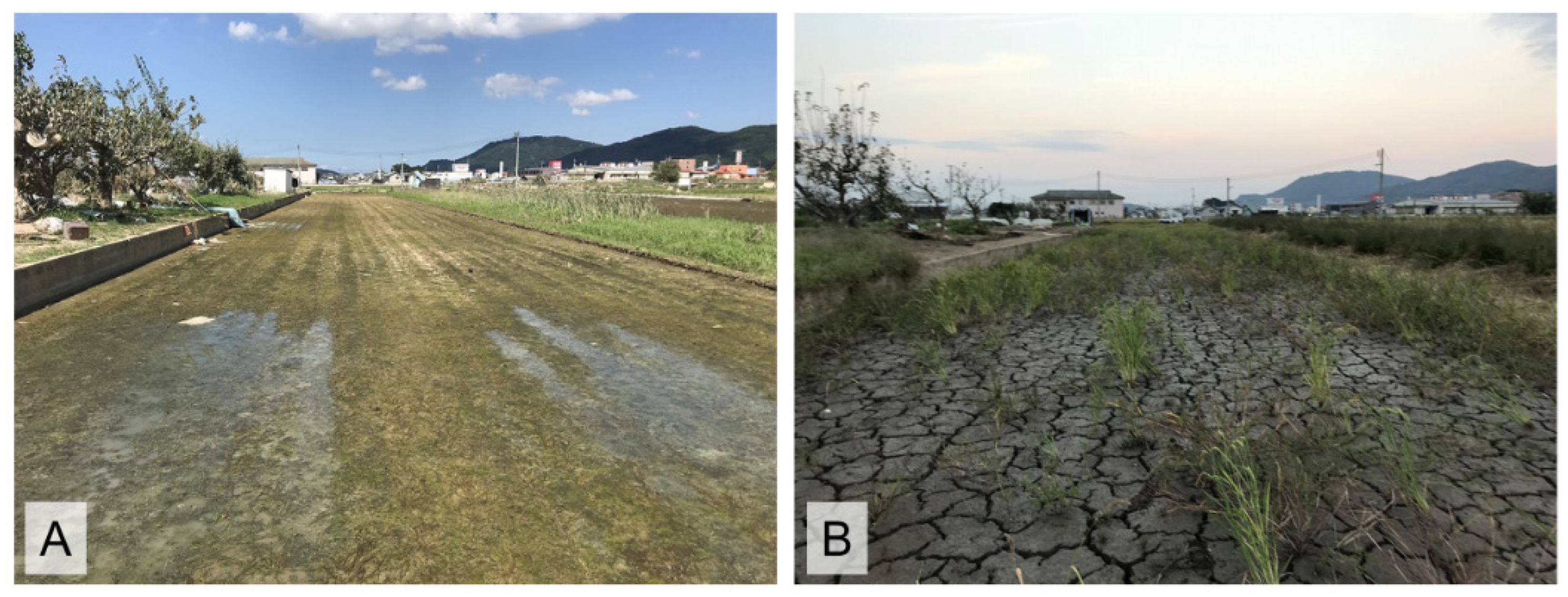

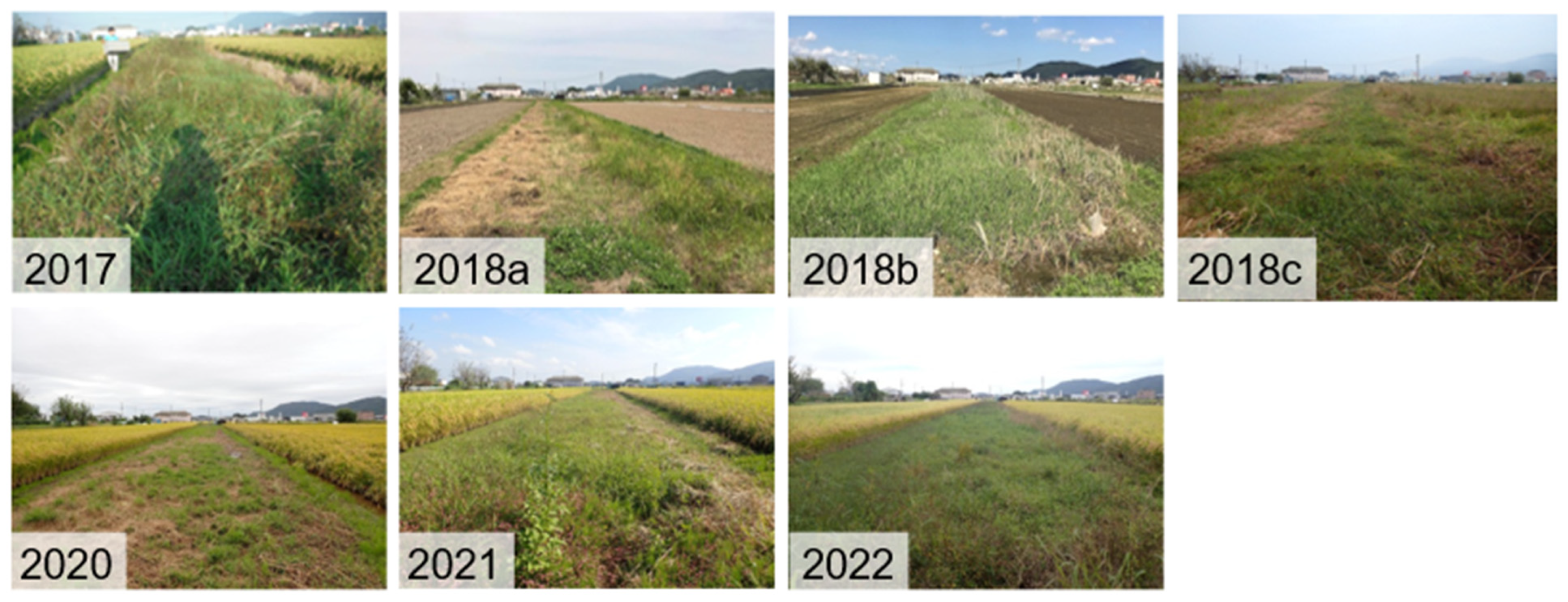

2.1. Study Site

2.2. Frog Surveys

2.3. Satistical Analyses

3. Results

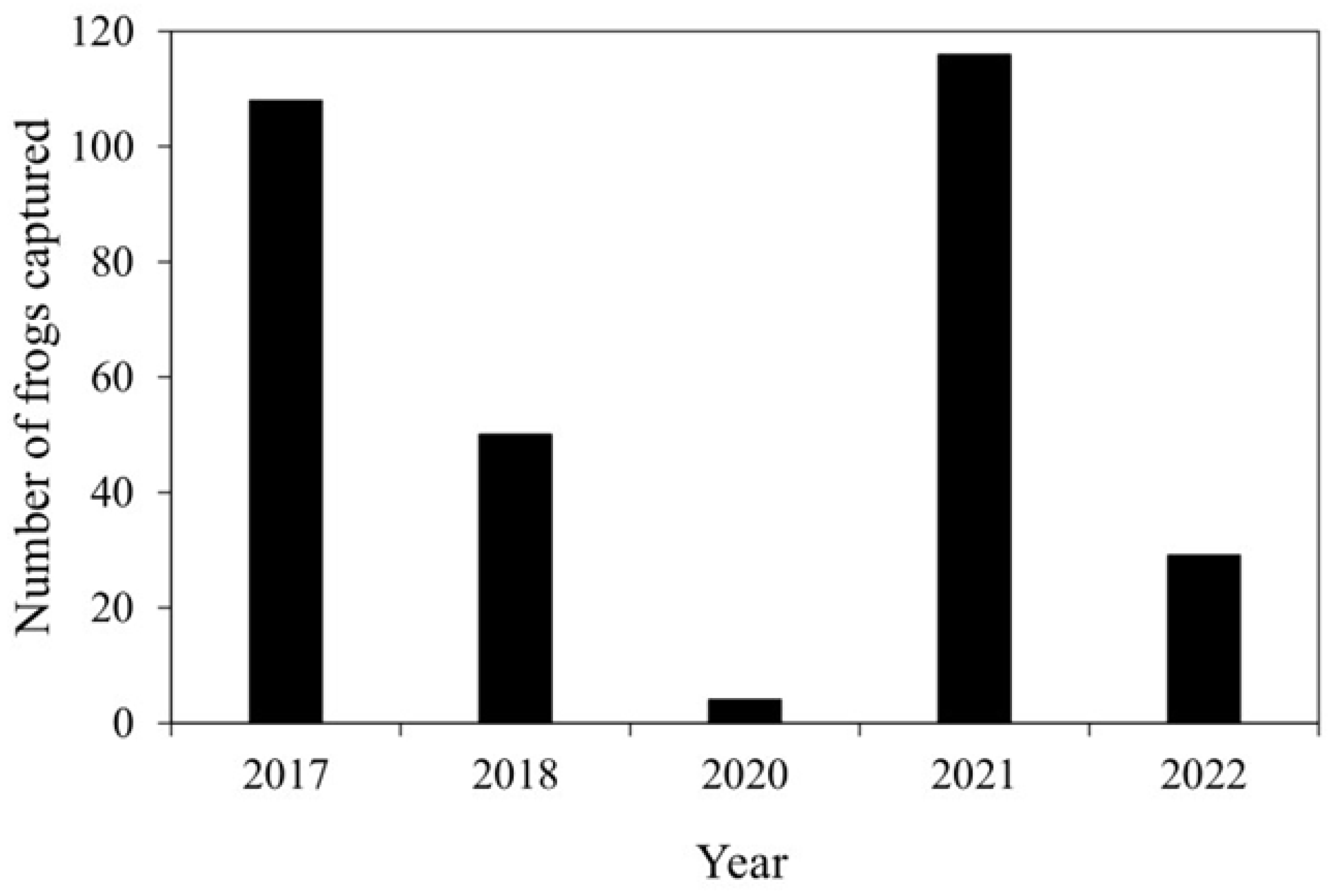

3.1. Number of Frogs Captured During the Survey Period

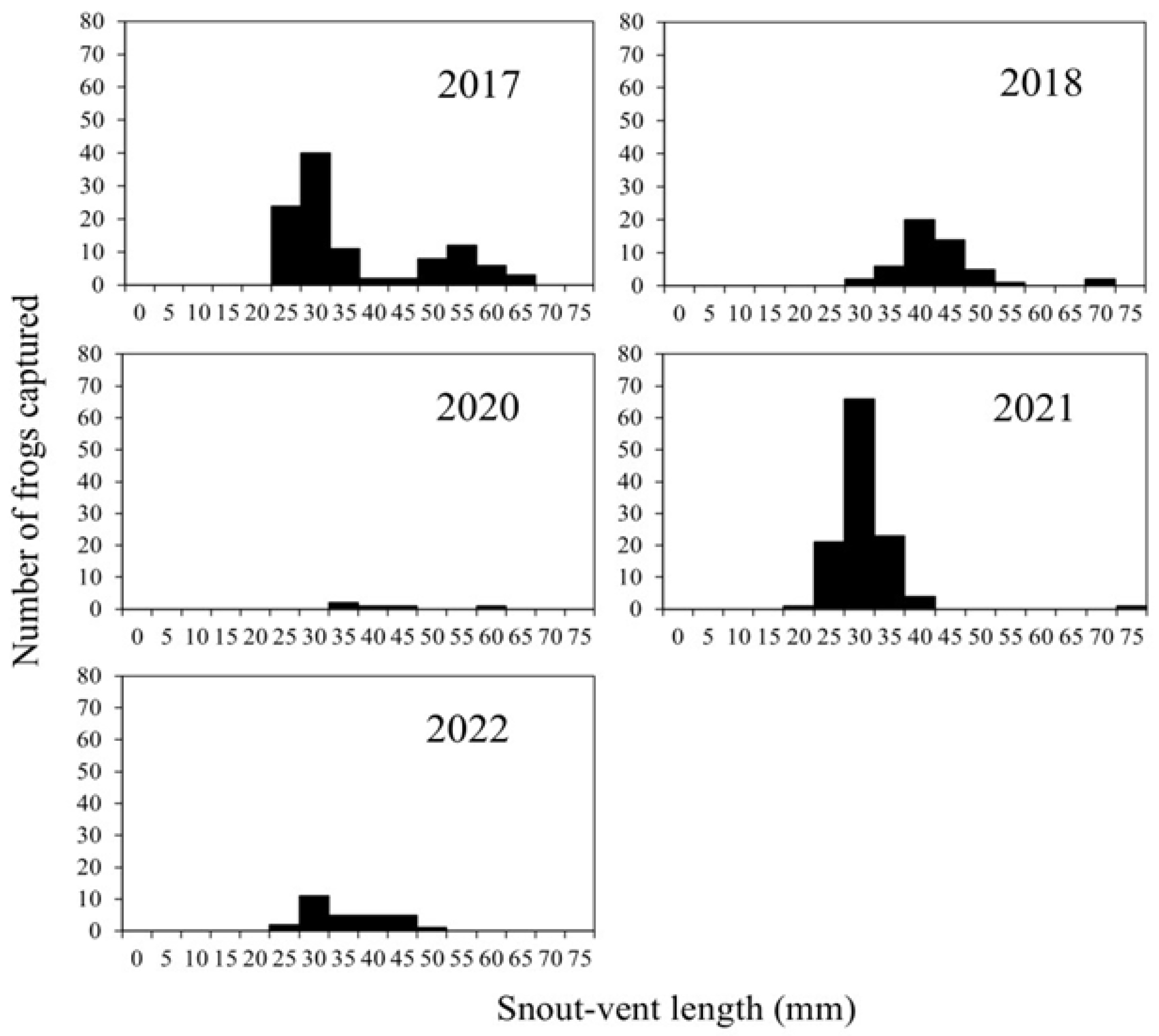

3.2. Comparison of Body Size Distribution Between the Survey Years

4. Discussion

4.1. Reproductive Pattern of P. porosus brevipodus Under Pre-Flood Conditions and Breeding Response During the 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster

4.2. Effects of the 2018 Flood, as Reflected in the Low Recruitment Observed in 2020

4.3. Importance of the Resumption of Rice Cultivation in 2019, as Indicated by Increased Recruitment in 2021

4.4. Time Lag Required for Population Dynamics to Stabilize, as Suggested by Capture Numbers up to 2022

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bobbink, R.; Whigham, D.F.; Beltman, B.; Verhoeven, J.T.A. Wetlands: Functioning, Biodiversity Conservation, and Restoration, Ecological Studies; Bobbink, R., Beltman, B., Verhoeven, J.T.A., Whigham, D.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; Volume 191, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler, P.S. Rice fields as temporary wetlands: A review. Isr. J. Zool. 2001, 47, 513–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elphick, S.C. Functional equivalency between rice fields and seminatural wetland habitats. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiritani, K. A Comprehensive List of Organisms Associated with Paddy Ecosystems in Japan; Institute of Agriculture and Nature, Itoshima & Biodiversity Agriculture Support Center: Machida, Japan, 2010; 427p. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, K. Indicators for functional agro-biodiversity: Outline of the research project. Plant Prot. 2010, 64, 600–604, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Watabe, K.; Mori, A.; Koizumi, N.; Takemura, T.; Park, M. Experiment for development of simple escape countermeasures for frogs falling into concrete canals. Trans. JSIDRE 2011, 79, 215–221, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, T. Chapter 12: Where did organisms exclusive to rice fields live before rice fields existed? In Why Do Diverse Organisms Live in Rice Fields? Otsuka, T., Mineta, T., Eds.; Kyoto University Press: Kyoto, Japan, 2020; pp. 255–273. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Eda, S.; Yamada, M. 4 Amphibians. In Okayama Prefecture Red Data Book 2020; Okayama Prefecture Wild Flora and Fauna Survey and Review Committee , Ed.; Okayama Prefecture Environmental Culture Department Natural Environment Division: Okayama, Japan, 2020; pp. 117–127. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. Manual for Survey and Evaluation of Indicator Species of Biodiversity Useful for Agriculture—I Survey Methods and Evaluation Methods. Available online: http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/archive/niaes/techdoc/shihyo/ (accessed on 26 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Mabi Town History Compilation Committee. Mabi Town History; Mabi Town History Compilation Committee: Okayama, Japan, 1979; 1282p. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa, T. Reproductive traits of the Rana nigromaculata-brevipoda complex in Japan. II. Egg-laying of Rana brevipoda brevipoda and R. nigromaculata in places dried up in early spring. Jpn. J. Herpetol. 1985, 11, 11–19, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Ito, K.; Saito, M.; Mori, Y.; Fukumasu, J.; Nakata, K. Wintering site environment for the Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Kurashiki, Okayama Prefecture, western Japan. Trans. Jpn. Soc. Irrig. Drain. Rural Eng. 2019, 87, I_179–I_187, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Okayama Prefecture. Record of the Heavy Rain Disaster in July 2018. Available online: https://www.pref.okayama.jp/page/653529.html (accessed on 26 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Tada, M.; Miyake, Y.; Nakashima, Y.; Ito, K.; Saito, M.; Nakata, K. Habitat preference of the endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in paddy levees and fallow paddy fields of Kurashiki, Okayama, western Japan. Ecol. Civ. Eng. 2023, 25, 71–85, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, K. Precious Natural Heritage of Okayama: Population of the Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog in Okayama. Takahashi River Basin Fed. Bull. Takahashi River 2013, 71, 78–91. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Japan Meteorological Agency. Climate Change Monitoring Report 2021, Japan. Available online: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/cpdinfo/monitor/index.html (accessed on 26 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Yoon, J.D.; Jang, M.H.; Joo, G.J. Effect of flooding on fish assemblages in small streams in South Korea. Limnology 2011, 12, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroon, F.J.; Ludwig, J.A. Response and recovery of fish and invertebrate assemblages following flooding in five tributaries of a sub-tropical river. Mar. Freshw. Res. 2010, 61, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cover, M.R.; de la Fuente, J.A.; Resh, V.H. Catastrophic disturbances in headwater streams: The long-term ecological effects of debris flows and debris floods in the Klamath Mountains, northern California. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2010, 67, 1596–1610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunga-Llauce, J.A.; Pacheco, A.S. Impacts of earthquakes and tsunamis on marine benthic communities: A review. Mar. Environ. Res. 2021, 171, 105481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasada, M.; Uchida, K.; Shinohara, N.; Yoshida, T. Ecosystem-based disaster risk reduction can benefit biodiversity conservation in a Japanese agricultural landscape. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 699201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, K.; Honma, A.; Furukawa, M.; Takakura, K.; Fujii, N.; Morii, K.; Terasawa, Y.; Nishida, T. Habitat partitioning of two closely related pond frogs, Pelophylax nigromaculatus and Pelophylax porosus brevipodus, during their breeding season. Evol. Ecol. 2020, 34, 855–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayzulin, A.I.; Chikhlyaev, I.V.; Ermakov, O.A.; Ruchin, A.B.; Lada, G.A. New data on the distribution and ecological peculiarities of the Edible Frog Pelophylax esculentus in the Mordovian Reserve and Smolny National Park. Inland Water Biol. 2025, 18, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigeta, S.; Suzuki, T.; Komaki, S.; Tojo, K. Changes over a 10-year period in the distribution ranges and genetic hybridization of three Pelophylax pond frogs in central Japan. Ecol. Evol. 2025, 15, e71856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, I.; Vershinin, X.; Vershinina, S.; Lebedinskii, A.; Trofimov, A.; Sitnikov, I.; Ito, M. Hybridogenesis in the water frogs from western Russian territory: Intrapopulation variation in genome elimination. Genes 2021, 12, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geospatial Information Authority of Japan. Information on the Heavy Rain in July 2018. Available online: https://www.gsi.go.jp/BOUSAI/H30.taihuu7gou.html (accessed on 26 March 2025). (In Japanese)

- Matsui, M.; Maeda, N. Encylopaedia of Japanese Frogs; Bun-ichi Sogo Shuppan: Tokyo, Japan, 2018; 272p. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Benaglia, T.; Chauveau, D.; Hunter, D.R.; Young, D. Mixtools: An R package for analyzing finite mixture models. J. Stat. Softw. 2009, 32, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venables, W.N.; Ripley, B.D. Modern Applied Statistics with S, 4th ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; 498p. [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa, T. Reproductive traits of the Rana nigromaculata brevipodus complex in Japan. I. Growth and egg-laying in Tatsuda and Saya, Aichi prefecture. Jpn. J. Herpetol. 1983, 10, 7–19, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, C.; Bryant, C.J. Possible interrelations among environmental toxicants, amphibian development, and decline of amphibian populations. Environ. Health Perspect. 1995, 103, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa, T.; Tanigawa, Y.; Serizawa, S. Reproductive traits of the Rana nigromaculata-porosa complex in Japan IV. Clutch size and ovum size. J. Herpetol. 1990, 13, 80–86, (In Japanese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naito, J.; Sakamura, A.; Nakayama, T.; Matsubara, C. The conservation of the Daruma Pond Frog (Rana porosa brevipoda) in the biotope area of Haizuka Dam. Hibakagaku 2014, 250, 1–27. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Amin, H.; Borzée, A. Understanding the distribution, behavioural ecology, and conservation status of Asian Pelophylax. Diversity 2024, 16, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of Models Selected as the Best Model/Did Not Converge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | k = 1 | k = 2 | k = 3 | k = 4 | k = 5 |

| 2017 | 0/0 | 788/0 | 171/0 | 33/0 | 8/0 |

| 2018 | 248/0 | 404/14 | 219/6 | 92/6 | 37/4 |

| 2021 | 566/0 | 290/314 | 66/310 | 35/294 | 43/270 |

| 2021 * | 847/0 | 140/0 | 13/0 | 0/0 | 0/0 |

| 2022 | 250/0 | 575/0 | 115/0 | 41/0 | 19/5 |

| First Cohort | Second Cohort | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| 2017 | 27.26 (26.51–28.12) | 3.23 (2.63–3.96) | 52.11 (49.30–54.28) | 5.72 (3.73–8.28) |

| 2018 | 39.77 (31.98–42.15) | 3.89 (0.21–9.26) | 52.13 (40.49–66.60) | 5.29 (0.08–14.17) |

| 2021 * | 28.30 (27.69–28.92) | 3.12 (2.84–3.78) | ||

| 2022 | 28.52 (25.88–33.17) | 2.60 (0.52–6.30) | 39.89 (34.71–43.23) | 3.43 (0.74–6.38) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakajima, R.; Azumi, D.; Tada, M.; Nakaichi, J.; Katsuhara, K.R.; Nakata, K. Impact of the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster on the Endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Rice Fields of Mabi Town, Kurashiki City, Western Japan: Changes in Population Structure over Five Years. Animals 2026, 16, 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030369

Nakajima R, Azumi D, Tada M, Nakaichi J, Katsuhara KR, Nakata K. Impact of the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster on the Endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Rice Fields of Mabi Town, Kurashiki City, Western Japan: Changes in Population Structure over Five Years. Animals. 2026; 16(3):369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030369

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakajima, Ryo, Daisuke Azumi, Masakazu Tada, Junya Nakaichi, Koki R. Katsuhara, and Kazuyoshi Nakata. 2026. "Impact of the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster on the Endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Rice Fields of Mabi Town, Kurashiki City, Western Japan: Changes in Population Structure over Five Years" Animals 16, no. 3: 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030369

APA StyleNakajima, R., Azumi, D., Tada, M., Nakaichi, J., Katsuhara, K. R., & Nakata, K. (2026). Impact of the July 2018 Heavy Rain Disaster on the Endangered Nagoya Daruma Pond Frog (Pelophylax porosus brevipodus) in Rice Fields of Mabi Town, Kurashiki City, Western Japan: Changes in Population Structure over Five Years. Animals, 16(3), 369. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16030369