Porcine FRZB (sFRP3) Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via the Wnt Signaling Pathway

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.2. C2C12 Cell Culture and RNA Interference

2.3. RNA Extraction and mRNA Level Measurement

2.4. Cell Proliferation Measurement

2.5. Transwell Migration Assay

2.6. Immunofluorescence (IF)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Tissue Distribution and Breed-Specific Expression of FRZB in Pigs

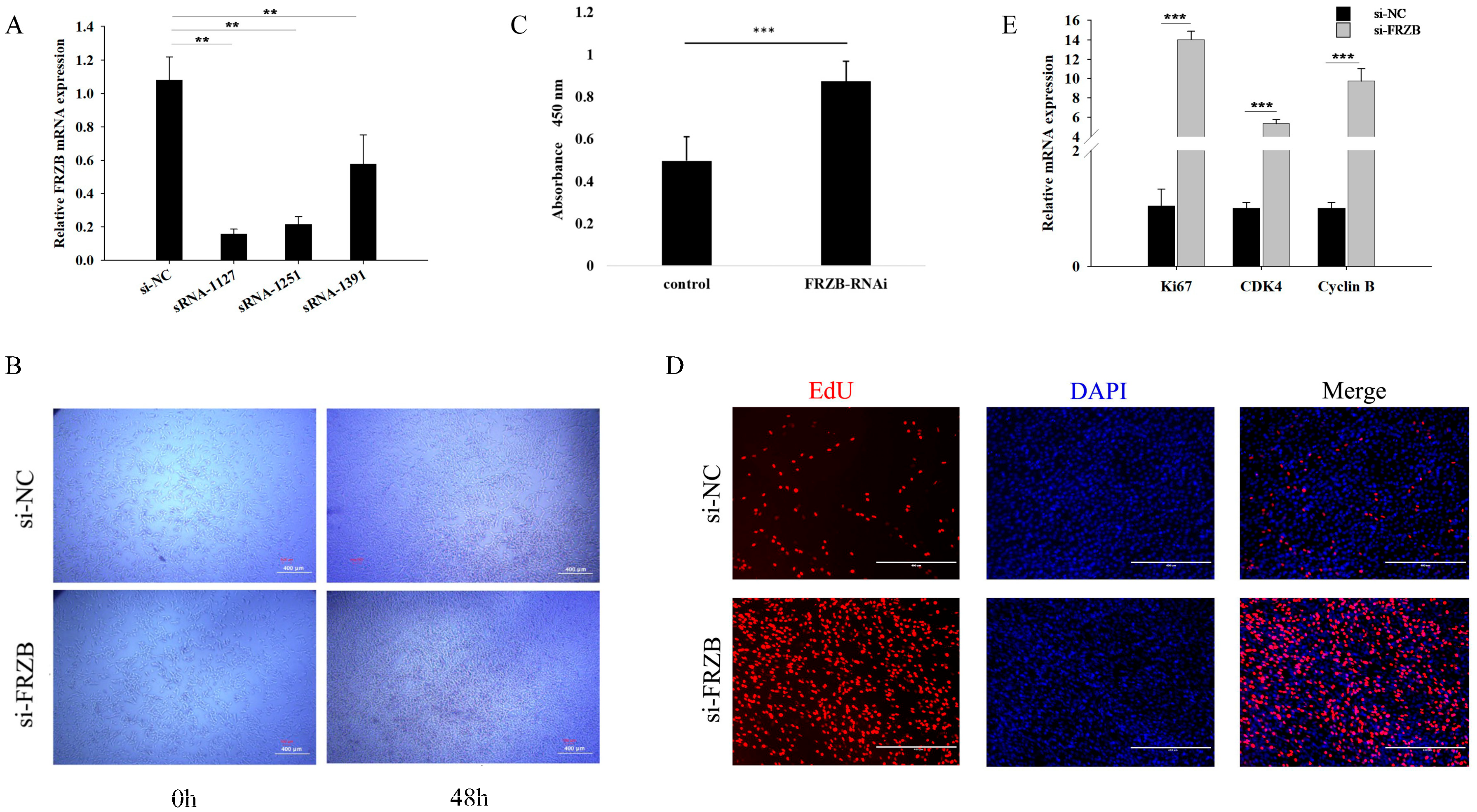

3.2. FRZB Knockdown Enhances Proliferation of C2C12 Myoblasts

3.3. FRZB Knockdown Markedly Increases Transwell Migration of C2C12 Myoblasts

3.4. FRZB Knockdown Accelerates Myogenic Differentiation and Augments Myotube Formation in C2C12 Cells

3.5. FRZB Knockdown Skews C2C12 Transcription Toward a Pro-Hypertrophic Profile

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| BF | Back fat |

| Bmp4 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 |

| CCK-8 | Cell counting kit-8 |

| CDK4 | Cyclin dependent kinase 4 |

| CRD | Cysteine-rich domain |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium |

| DSP | Diannan small-eared pig |

| EdU | 5-Ethynyl-2-deoxyuridine |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| Foxo3 | Forkhead box o3 |

| FRZB | Frizzled-related protein |

| Fst | Follistatin |

| IF | Immunofluorescence |

| LD | Longissimus dorsi |

| LL | Landrace pig |

| LW | Large White pig |

| MRFs | Myogenic regulatory factors |

| MyHC | Myosin heavy chain |

| MyoD | Myogenic differentiation antigen |

| MyoG | Myogenin |

| Nog | Noggin |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| qRT-PCR | quantitative real-time PCR |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| sFRP3 | secreted frizzled-related protein 3 |

| sqRT-PCR | semi-quantitative reverse transcription PCR |

| TP | Tibetan pig |

| WJ | Wujin pig |

| YY | Yorkshire pig |

References

- Mohammadabadi, M.; Bordbar, F.; Jensen, J.; Du, M.; Guo, W. Key Genes Regulating Skeletal Muscle Development and Growth in Farm Animals. Animals 2021, 11, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, M.; Vincent, S.D. Distinct and dynamic myogenic populations in the vertebrate embryo. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2009, 19, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigmore, P.M.; Stickland, N.C. Muscle development in large and small pig fetuses. J. Anat. 1983, 137, 235–245. [Google Scholar]

- Reis, E.P.; Paixao, D.M.; Brustolini, O.J.; Silva, F.F.; Silva, W.; Araujo, F.M.; Salim, A.C.; Oliveira, G.; Guimaraes, S.E. Expression of myogenes in longissimus dorsi muscle during prenatal development in commercial and local Piau pigs. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2016, 39, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, J.D.; Kothary, R. The myogenic kinome: Protein kinases critical to mammalian skeletal myogenesis. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, D.; Zhang, J.; Raza, S.H.A.; Song, Y.; Jiang, C.; Song, X.; Wu, H.; Alotaibi, M.A.; Albiheyri, R.; Al-Zahrani, M.; et al. Interaction of MyoD and MyoG with Myoz2 gene in bovine myoblast differentiation. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 152, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skapek, S.X.; Rhee, J.; Kim, P.S.; Novitch, B.G.; Lassar, A.B. Cyclin-mediated inhibition of muscle gene expression via a mechanism that is independent of pRB hyperphosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996, 16, 7043–7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skapek, S.X.; Rhee, J.; Spicer, D.B.; Lassar, A.B. Inhibition of myogenic differentiation in proliferating myoblasts by cyclin D1-dependent kinase. Science 1995, 267, 1022–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi Majd, S.; Gholami, M.; Bazgir, B. PAX7 and MyoD Proteins Expression in Response to Eccentric and Concentric Resistance Exercise in Active Young Men. Cell J. 2023, 25, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Chamba, Y.; Zhang, B.; Shang, P.; Zhang, H.; Wu, C. Correction: Identification of Genes Related to Growth and Lipid Deposition from Transcriptome Profiles of Pig Muscle Tissue. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0172930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.T.; Kohn, A.D.; De Ferrari, G.V.; Kaykas, A. WNT and beta-catenin signalling: Diseases and therapies. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2004, 5, 691–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawano, Y.; Kypta, R. Secreted antagonists of the Wnt signalling pathway. J. Cell Sci. 2003, 116, 2627–2634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Hao, M.; Zhu, J.; Yi, L.; Cheng, W.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, S. Comparison of differentially expressed genes in longissimus dorsi muscle of Diannan small ears, Wujin and landrace pigs using RNA-seq. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1296208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgwi, I.H.; Halas, V.; Grunvald, P.; Schiavon, S.; Jocsak, I. Genes Related to Fat Metabolism in Pigs and Intramuscular Fat Content of Pork: A Focus on Nutrigenetics and Nutrigenomics. Animals 2022, 12, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentzinger, C.F.; Wang, Y.X.; Rudnicki, M.A. Building muscle: Molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012, 4, a008342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, N.A.; Bentzinger, C.F.; Sincennes, M.C.; Rudnicki, M.A. Satellite cells and skeletal muscle regeneration. Compr. Physiol. 2015, 5, 1027–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Maltzahn, J.; Chang, N.C.; Bentzinger, C.F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Wnt signaling in myogenesis. Trends Cell Biol. 2012, 22, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borello, U.; Coletta, M.; Tajbakhsh, S.; Leyns, L.; Robertis, E.M.D.; Buckingham, M.; Cossu, G. Transplacental delivery of the Wnt antagonist Frzb1 inhibits development of caudal paraxial mesoderm and skeletal myogenesis in mouse embryos. Development 1999, 126, 4247–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scardigli, R.; Gargioli, C.; Tosoni, D.; Borello, U.; Sampaolesi, M.; Sciorati, C.; Cannata, S.; Clementi, E.; Brunelli, S.; Cossu, G. Binding of sFRP-3 to EGF in the extra-cellular space affects proliferation, differentiation and morphogenetic events regulated by the two molecules. PLoS ONE 2008, 3, e2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagathu, C.; Christodoulides, C.; Virtue, S.; Cawthorn, W.P.; Franzin, C.; Kimber, W.A.; Nora, E.D.; Campbell, M.; Medina-Gomez, G.; Cheyette, B.N. Dact1, a nutritionally regulated preadipocyte gene, controls adipogenesis by coordinating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling network. Diabetes 2009, 58, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestwich, T.C.; MacDougald, O.A. Wnt/β-catenin signaling in adipogenesis and metabolism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 612–617. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.E.; Hemati, N.; Longo, K.A.; Bennett, C.N.; Lucas, P.C.; Erickson, R.L.; MacDougald, O.A. Inhibition of adipogenesis by Wnt signaling. Science 2000, 289, 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Chow, S.K.H.; Cui, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, Q.; Chai, S.; Wong, R.M.Y.; Zhang, N.; Cheung, W.H. Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway as an important mediator in muscle and bone crosstalk: A systematic review. J. Orthop. Transl. 2024, 47, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Chu, Q.; Shi, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Lu, J.; Li, L. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: Mechanisms and therapeutic advances. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, Q.; Zhang, B.; Lu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ban, D.; Zhang, H. Single nucleotide polymorphism scanning and expression of the FRZB gene in pig populations. Gene 2014, 543, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NY/T 65-2004; Feeding Standard for Swine. Ministry of Agriculture of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2004.

- Ye, J.; Coulouris, G.; Zaretskaya, I.; Cutcutache, I.; Rozen, S.; Madden, T.L. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Shang, P.; Zhang, B.; Tian, X.; Nie, R.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H. Function of the Porcine TRPC1 Gene in Myogenesis and Muscle Growth. Cells 2021, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leyns, L.; Bouwmeester, T.; Kim, S.-H.; Piccolo, S.; De Robertis, E.M. Frzb-1 is a secreted antagonist of Wnt signaling expressed in the Spemann organizer. Cell 1997, 88, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polesskaya, A.; Seale, P.; Rudnicki, M.A. Wnt signaling induces the myogenic specification of resident CD45+ adult stem cells during muscle regeneration. Cell 2003, 113, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzahor, E.; Kempf, H.; Mootoosamy, R.C.; Poon, A.C.; Abzhanov, A.; Tabin, C.J.; Dietrich, S.; Lassar, A.B. Antagonists of Wnt and BMP signaling promote the formation of vertebrate head muscle. Genes. Dev. 2003, 17, 3087–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bovolenta, P.; Esteve, P.; Ruiz, J.M.; Cisneros, E.; Lopez-Rios, J. Beyond Wnt inhibition: New functions of secreted Frizzled-related proteins in development and disease. J. Cell Sci. 2008, 121, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esteve, P.; Sandonìs, A.; Cardozo, M.; Malapeira, J.; Ibanez, C.; Crespo, I.; Marcos, S.; Gonzalez-Garcia, S.; Toribio, M.L.; Arribas, J. SFRPs act as negative modulators of ADAM10 to regulate retinal neurogenesis. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Dagnone, D.; Jones, P.J.; Smith, H.; Paddags, A.; Hudson, R.; Janssen, I. Reduction in obesity and related comorbid conditions after diet-induced weight loss or exercise-induced weight loss in men: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med. 2000, 133, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, T.; Olea-Flores, M.; Imbalzano, A.N. Regulation of the Wnt signaling pathway during myogenesis by the mammalian SWI/SNF ATPase BRG1. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1160227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwan, T.; Kazamel, M.; Thoenes, K.; Si, Y.; Jiang, N.; King, P.H. Wnt antagonist FRZB is a muscle biomarker of denervation atrophy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 16679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Brolosy, M.A.; Kontarakis, Z.; Rossi, A.; Kuenne, C.; Gunther, S.; Fukuda, N.; Kikhi, K.; Boezio, G.L.M.; Takacs, C.M.; Lai, S.L.; et al. Genetic compensation triggered by mutant mRNA degradation. Nature 2019, 568, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Brolosy, M.A.; Stainier, D.Y.R. Genetic compensation: A phenomenon in search of mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodewyckx, L.; Cailotto, F.; Thysen, S.; Luyten, F.P.; Lories, R.J. Tight regulation of wingless-type signaling in the articular cartilage—Subchondral bone biomechanical unit: Transcriptomics in Frzb-knockout mice. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nie, J.; Fu, Y.; Hao, X.; Yan, D.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, H. Porcine FRZB (sFRP3) Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via the Wnt Signaling Pathway. Animals 2026, 16, 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020276

Nie J, Fu Y, Hao X, Yan D, Zhang B, Zhang H. Porcine FRZB (sFRP3) Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via the Wnt Signaling Pathway. Animals. 2026; 16(2):276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020276

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Jingru, Yu Fu, Xin Hao, Dawei Yan, Bo Zhang, and Hao Zhang. 2026. "Porcine FRZB (sFRP3) Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via the Wnt Signaling Pathway" Animals 16, no. 2: 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020276

APA StyleNie, J., Fu, Y., Hao, X., Yan, D., Zhang, B., & Zhang, H. (2026). Porcine FRZB (sFRP3) Negatively Regulates Myogenesis via the Wnt Signaling Pathway. Animals, 16(2), 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020276