Fatty Liver in Fish: Metabolic Drivers, Molecular Pathways and Physiological Solutions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Factors and Mechanism of Triggering Fatty Liver

2.1. Factors

2.1.1. Feed Composition

| Feed Composition | Impact | Fish | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dietary lipid | Excessive fat intake can hinder growth and disrupt lipid metabolism, inducing liver damage in fish. | Tilapia | Qiang et al. (2017); Tao et al. (2018) [25,31] |

| Fructose | Fructose treatment induces hepatic lipid accumulation, inflammation, and oxidative stress. | Zebrafish fry | Sapp et al. (2014) [37] |

| Fish oil | Fish oil is an ideal lipid source for a fish-based diet. | Tilapia | Kohen et al. (2002); Radovanović et al. (2010); Stoneham et al. (2018) [38,39,41] |

2.1.2. High Feeding Rate

2.1.3. Environment

2.2. Mechanism

2.2.1. Abnormal Fat Accumulation

2.2.2. Oxidative Stress

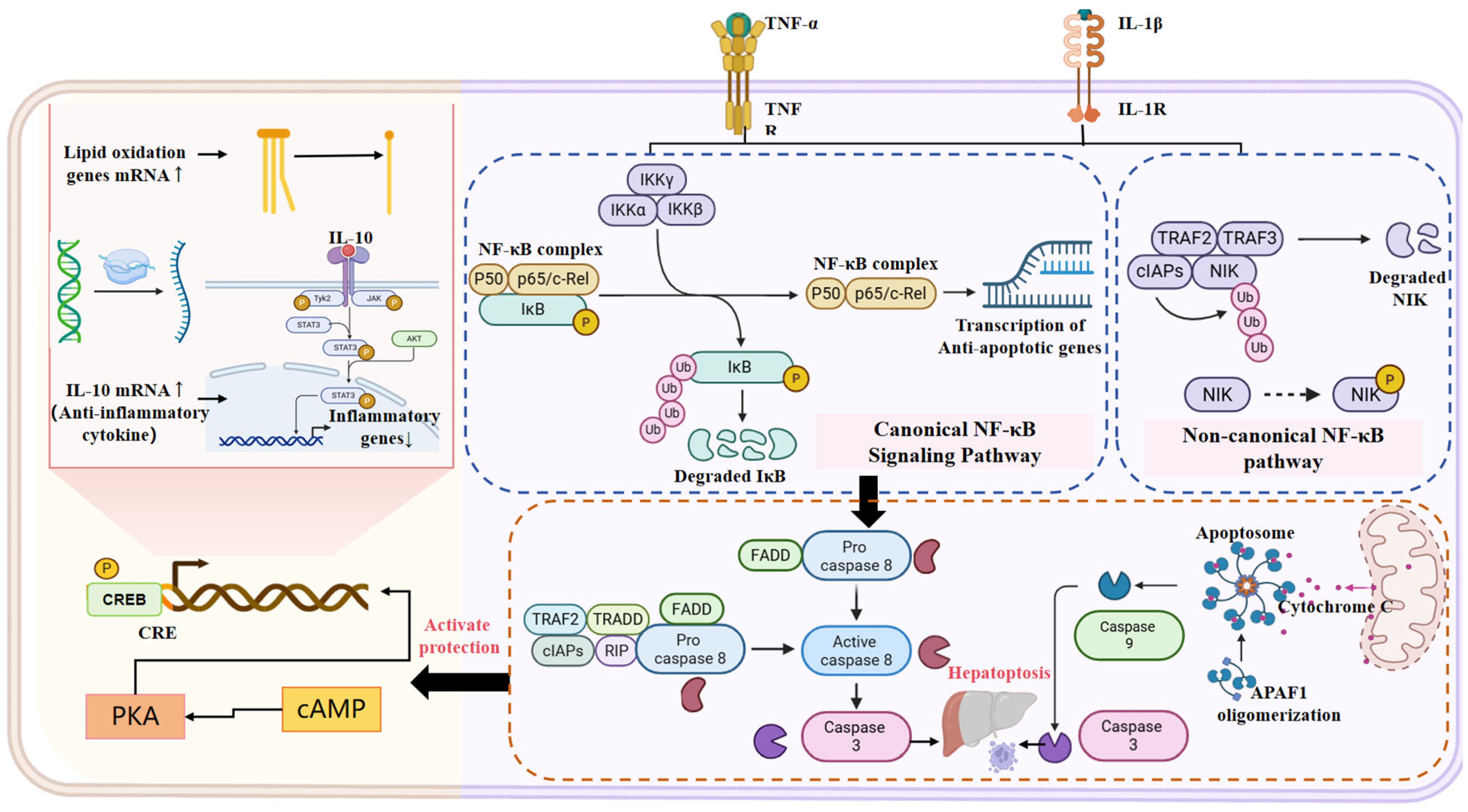

2.2.3. Inflammation

2.2.4. Cell Death

3. Proposed Strategies and Solutions

3.1. Environmental Adaptability

3.2. Genetic Improvement Techniques

3.3. Changing Feeding Habits and Contents

3.4. Rapamycin

4. Conclusions and Future Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zou, J.M.; Song, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Lu, J.C. Research Progress on the Formation Mechanism of Nutritional Quality of Main Freshwater Aquatic Products During the Conversion of Aquaculture Models. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. 2019, 35, 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Cao, Q.; Yan, M.; Ye, Y.; Faggio, C.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Dietary vitamin D3 improves growth performance and hepatic glycolipid metabolism in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2025, 327, 116429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.D.; Kim, K.W.; Yong, J.K.; Lee, S.M. Influence of lipid level and supplemental lecithin in diet on growth, feed utilization and body composition of juvenile flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) in suboptimal water temperatures. Aquaculture 2006, 251, 484–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhang, Y.; Cao, Q.; Shan, H.; Zong, J.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; et al. Hepatic Oxidative Stress and Cell Death Influenced by Dietary Lipid Levels in a Fresh Teleost. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.M.; Han, G.M.; Lv, F.; Yang, W.P.; Huang, J.T.; Yin, X.L. Effects of Dietary Lipid Levels on Growth Performance, Apparent Digestibility Coefficients of Nutrients, and Blood Characteristics of Juvenile Crucian Carp (Carassius auratus gibelio). Turk. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, I.; Glencross, B.; Santigosa, E. The importance of essential fatty acids and their ratios in aquafeeds to enhance salmonid production, welfare, and human health. Front. Anim. Sci. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.M. Safety Production and Inspection Technology of Animal Products; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D.K.; Kim, K.D.; Seo, J.Y.; Lee, S.M. Effects of Dietary Lipid Source and Level on Growth Performance, Blood Parameters and Flesh Quality of Sub-adult Olive Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 869–879. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Z.Y. Causes and related thoughts of fatty liver in farmed fish. J. Fish. China 2014, 38, 1628–1638. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.B. The causes of fatty liver formation in fish and anti-fatty liver factors. Jiangxi Aquat. Sci. Technol. 2006, 2, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Guo, D.J. Inducing factors and regulatory measures of nutritional fatty liver in fish. Beijing Aquat. Prod. 2007, 6, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Shan, H.; Zhao, J.; Deng, J.; Xu, M.; Kang, H.; Li, T.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Liver fibrosis in fish research: From an immunological perspective. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2023, 139, 108885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A.Y.; Ning, L.J.; Chen, L.Q.; Chen, Y.L.; Xing, Q.; Li, J.M.; Qiao, F.; Li, D.L.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. Systemic adaptation of lipid metabolism in response to low- and high-fat diet in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eide, M.; Goksøyr, A.; Yadetie, F.; Gilabert, A.; Bartosova, Z.; Frøysa, H.G.; Fallahi, S.; Zhang, X.; Blaser, N.; Jonassen, I.; et al. Integrative omics-analysis of lipid metabolism regulation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor a and b agonists in male Atlantic cod. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1129089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheridan, M.A.; Kao, Y.H. Regulation of metamorphosis-associated changes in the lipid metabolism of selected vertebrates. Am. Zool 1998, 38, 350–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, I.; Gutiérrez, J. Fasting and starvation. Biochem. Mol. Biol. Fishes 1995, 4, 393–434. [Google Scholar]

- Tocher, D.R. Metabolism and functions of lipids and fatty acids in teleost fish. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2003, 11, 107–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minghetti, M.; Leaver, M.J. A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ gene from the marine teleost, the Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2010, 44, 355–367. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, R.; Cao, L.P.; Du, J.L.; He, Q.; Gu, Z.Y.; Jeney, G.; Xu, P.; Yin, G.J. Effects of high-fat diet on antioxidative status, apoptosis and inflammation in liver of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) via Nrf2, TLRs and JNK pathways. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2020, 104, 391–401. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.X.; Qiao, F.; Zhang, M.L.; Chen, L.Q.; Du, Z.Y.; Luo, Y. Double-edged effect of sodium citrate in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus): Promoting lipid and protein deposition vs. causing hyperglycemia and insulin resistance. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 14, 303–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Zhou, L.; Lu, W.J.; Du, W.X.; Mi, X.Y.; Li, Z.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, Z.W.; Wang, Y.; Duan, M.; et al. Comparative transcriptomic analysis reveals an association of gibel carp fatty liver with ferroptosis pathway. BMC Genom. 2021, 22, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Z.; Liu, H.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, J. Dietary Methionine Hydroxy Analog Regulates Hepatic Lipid Metabolism via SIRT1/AMPK Signaling Pathways in Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmodies. Biology 2025b, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, G.; Xu, J.; Teng, Y.; Ding, C.; Yan, B. Effects of dietary lipid levels on the growth, digestive enzyme, feed utilization and fatty acid composition of Japanese sea bass (Lateolabrax japonicus L.) reared in freshwater. Aquacult. Res. 2010, 41, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.Y.; Guo, X.L.; Yang, X.Y.; Niu, Z.Y.; Li, S.H.; Wang, S.Y.; Chen, H.; Pan, L. PTEN and rapamycin inhibiting the growth of K562 cells through regulating mTOR signaling pathway. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. Vol. 2008, 27, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Qiang, J.; He, J.; Yang, H.; Sun, Y.Z.; Tao, Y.F.; Xu, P.; Zhu, Z.X. Dietary lipid require ments of larval genetically improved farmed tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, and effects on growth performance, expression of digestive enzyme genes, and immune response. Aquacult. Res. 2017, 48, 2827–2840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.F.; Dai, Y.J.; Liu, M.Y.; Yuan, X.Y.; Wang, C.C.; Huang, Y.Y.; Liu, W.B.; Jiang, G.Z. High-fat diet induces aberrant hepatic lipid secretion in blunt snout bream by activating endoplasmic reticulum stress-associated IRE1/XBP1 pathway. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2019, 1864, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, D.; Wang, H.; Chen, X. Hepatic lipid metabolism and oxidative stress responses of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) fed diets of two different lipid levels against Aeromonas hydrophila infection. Aquaculture 2019, 509, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limbu, S.M.; Ma, Q.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. High fat diet worsens the adverse effects of antibiotic on intestinal health in juvenile Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 680, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.J.; Cao, X.F.; Zhang, D.D.; Li, X.F.; Liu, W.B.; Jiang, G.Z. Chronic inflammation is a key to inducing liver injury in blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed with high-fat diet. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2019, 97, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.L.; Xu, W.N.; Li, X.F.; Liu, W.B.; Wang, L.N.; Zhang, C.N. Hepatic triacylglycerol secretion, lipid transport and tissue lipid uptake in blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala) fed high-fat diet. Aquaculture 2013, 408, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.F.; Qiang, J.; Bao, J.W.; Chen, D.J.; Yin, G.J.; Xu, P.; Zhu, H.J. Changes in Physiological Parameters, Lipid Metabolism, and Expression of MicroRNAs in Genetically Improved Farmed Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) With Fatty Liver Induced by a High-Fat Diet. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Xu, P.; Wen, H.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; He, J.; He, C.; Kong, C.; Li, X.; Li, H.; et al. A High-Fat-Diet-Induced Microbiota Imbalance Correlates with Oxidative Stress and the Inflammatory Response in the Gut of Freshwater Drum (Aplodinotus grunniens). Antioxidants 2024, 13, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.Q.; Liu, W.B.; Zhou, M.; Dai, Y.J.; Xu, C.; Tian, H.Y.; Xu, W.N. Effects of berberine on the growth and immune performance in response to ammonia stress and high-fat dietary in blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 55, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.X.; Qian, Y.F.; Zhou, W.H.; Wang, J.X.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Luo, Y.; Qiao, F.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. The Adaptive Characteristics of Cholesterol and Bile Acid Metabolism in Nile Tilapia Fed a High-Fat Diet. Aquac. Nutr. 2022, 2022, 8016616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawasaki, T.; Igarashi, K.; Koeda, T.; Sugimoto, K.; Nakagawa, K.; Hayashi, S.; Yamaji, R.; Inui, H.; Fukusato, T.; Yamanouchi, T. Rats fed fructose-enriched diets have characteristics of nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis. J. Nutr. 2009, 139, 2067–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Yamanouchi, T. The role of fructose-enriched diets in mechanisms of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2012, 23, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapp, V.; Gaffney, L.; EauClaire, S.F.; Matthews, R.P. Fructose leads to hepatics nml nteatosis in zebrafish that is reversed by mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition. Hepatology 2014, 60, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohen, R.; Nyska, A. Oxidation of biological systems: Oxidative stress phenomena, antioxidants, redox reactions, and methods for their quantification. Toxicol. Pathol. 2002, 30, 620–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, T.B.; Borkovi-Miti, S.S.; Perendija, B.R.; Despotovi Svetlana, S.G.; Pavlovi, S.Z.; Caki, P.D.; Saii Zorica, Z.S. Superoxide dismutase and catalase activities in the liver and muscle of barbel (Barbus barbus) and its intestinal parasite (Pomphoryinchus laevis) from the Danube river. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2010, 62, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, X.; Ribas, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Dietary Cottonseed Protein Substituting Fish Meal Induces Hepatic Ferroptosis Through SIRT1-YAP-TRFC Axis in Micropterus salmoides: Implications for Inflammatory Regulation and Liver Health. Biology 2025, 14, 748. [Google Scholar]

- Stoneham, T.R.; Kuhn, D.D.; Taylor, D.P.; Neilson, A.P.; Smith, S.A.; Gatlin, D.M.; Chu, H.S.S.; O’Keefe, S.F. Production of omega-3 enriched tilapia through the dietary use of algae meal or fish oil: Improved nutrient value of fillet and offal. PloS ONE 2018, 13, e0194241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Li, X.; Han, F.; Li, E.; Qin, J.G.; Chen, L. Time-dependent effects of high-fat diet on muscle nutrient composition and texture properties in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Rep. 2025, 37, 102189. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobazzi, V.; Infantino, V. Citrate—New functions for an old metabolite. Biol. Chem. 2014, 395, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.J.; Yang, J.; Qu, H.T. Effects of high feeding rate on hepatic antioxidant, immune function and lipid metabolism in juvenile largemouth bronze gudgeon (Coreius guichenoti). J. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 35, 5870–5885. [Google Scholar]

- Tech, C.Y.; Ng, W.K. The implications of substituting dietary fish oil with vegetable oils on the growth performance, fillet fatty acid profile and modulation of the fatty acid elongase, desaturase and oxidation activities of red hybrid tilapia, Oreochromis sp. Aquaculture 2016, 465, 311–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanck, M.W.T.; Booms, G.H.R.; Eding, E.H.; Wendelaar Bonga, S.E.; Komen, J. Cold shocks: A stressor for common carp. J. Fish Biol. 2000, 57, 881–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawall, H.; Torres, J.; Sidell, B.; Somero, G. Metabolic cold adaptation in Antarctic fishes: Evidence from enzymatic activities of brain. Mar. Biol. 2002, 140, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, R.J.; Hennessey, T.M. Cold tolerance and homeoviscous adaptation in freshwater alewives (Alosa pseudoharengus). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2003, 29, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, N.; Guerra-Castro, E.; Diaz, F.; Rodríguez-Fuentes, G.; Simoes, N.; Robertson, D.R.; Rosas, C. Cold temperature tolerance of the alien Indo- Pacific damselfish Neopomacentrus cyanomos from the Southern Gulf of Mexico. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020, 524, 151308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Sun, J.; Chang, Z.G.; Gou, N.N.; Wu, W.Y.; Luo, X.L.; Zhou, J.S.; Yu, H.B.; Ji, H. Energy response and fatty acid metabolism in Onychostoma macrolepis exposed to low-temperature stress. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 94, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Y.; Limbu, S.M.; Zhao, S.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.L.; Qiao, F.; Du, Z.Y. Dietary L-carnitine supplementation recovers the increased pH and hardness in fillets caused by high-fat diet in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Food Chem. 2022, 382, 132367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Z. Effects of Hypoxia Stress on Oxidative Stress, Gut Microbiota, and Immune related Genes in Juvenile Rachycentron canadum. Master′s Thesis, Guangdong Ocean University, Zhanjiang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Shen, X.; Yuan, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, T.; Wu, H.; Wu, Q.; Fan, Y.; et al. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein resists hepatic oxidative stress by regulating lipid droplet homeostasis. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 3213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.C.; Limbu, S.M.; Wang, J.G.; Wang, M.; Chen, L.Q.; Qiao, F.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. Dietary docosahexaenoic acid reduces fat deposition and alleviates liver damage induced by D-galactosamine and lipopolysaccharides in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 268, 109603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arechavala-Lopez, P.; Cabrera-Álvarez, M.J.; Maia, C.M.; Saraiva, J.L. Environmental enrichment in fish aquaculture: A review of fundamental and practical aspects. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 1197–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; He, L.; Shan, H.; Faggio, C.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, J. 18β-Glycyrrhetinic acid mitigates adverse effects of high fat diet on liver fibrosis in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) by reducing mitochondrial Ca2+ level. Anim. Nutr. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Stapleton, D.S.; Schueler, K.L.; Rabaglia, M.E.; Oler, A.T.; Keller, M.P.; Kendziorski, C.M.; Broman, K.W.; Yandell, B.S.; Schadt, E.E.; et al. Tsc2, a positional candidate gene underlying a quantitative trait locus for hepatic steatosis. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yecies, J.L.; Zhang, H.H.; Menon, S.; Liu, S.; Yecies, D.; Lipovsky, A.I.; Gorgun, C.; Kwiatkowski, D.J.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Lee, C.H.; et al. Akt stimulates hepatic SREBP1c and lipogenesis through parallel mTORC1-dependent and independent pathways. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenerson, H.L.; Yeh, M.M.; Yeung, R.S. Tuberous sclerosis complex-1 deficiency attenuates diet-induced hepatic lipid accumulation. PloS ONE 2011, 6, e18075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, T.R.; Sengupta, S.S.; Harris, T.E.; Carmack, A.E.; Kang, S.A.; Balderas, E.; Guertin, D.A.; Madden, K.L.; Carpenter, A.E.; Finck, B.N.; et al. mTOR complex 1 regulates lipin 1 localization to control the SREBP pathway. Cell 2011, 146, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; He, G.; Mai, K.; Xu, W.; Zhou, H.; Wang, X.; Mei, L. Chronic rapamycin treatment on the nutrient utilization and metabolism of juvenile turbot (Psetta maxima). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Gu, W.; Sun, P.; Bai, Q.; Wang, B. Transcriptome Analyses Reveal Lipid Metabolic Process in Liver Related to the Difference of Carcass Fat Content in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Int. J. Genom. 2016, 2016, 7281585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushchak, V.I. Contaminant-induced oxidative stress in fish: A mechanistic approach. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 42, 711–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sies, H.; Jones, D.P. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) as pleiotropic physiological signalling agents. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittler, R.; Zandalinas, S.I.; Fichman, Y.; Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species signalling in plant stress responses. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nathan, C.; Cunningham-Bussel, A. Beyond oxidative stress: An immunologist’s guide to ROS. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2013, 13, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sies, H. Oxidative stress: A concept in redox biology and medicine. Redox Biol. 2015, 4, 180–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circu, M.L.; Aw, T.Y. Reactive oxygen species, cellular redox systems, and apoptosis. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2010, 48, 749–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zulfahmi, I.; Batubara, A.S.; Perdana, A.W.; Rahmah, A.; Nafis, B.; Ali, R.; Rahman, M.M. Chronic exposure to palm oil mill effluent induces oxidative stress and histopathological changes in zebrafish (Danio rerio). J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 490, 137844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Jin, M.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zong, J.; Shan, H.; Kang, H.; Xu, M.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Oxytetracycline-induced oxidative liver damage by disturbed mitochondrial dynamics and impaired enzyme antioxidants in largemouth bass (Microprerus salmoides). Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 261, 106616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Cao, Q.; Jiang, J. miRNA-seq analysis of liver tissue from largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) in response to oxytetracycline and enzyme-treated soy protein. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part D Genom. Proteom. 2024, 49, 101202. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, S.J. Ferroptosis: Bug or feature? Immunol. Rev. 2017, 277, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesilova, Z.; Yaman, H.; Oktenli, C.; Ozcan, A.; Uygun, A.; Cakir, E.; Sanisoglu, S.Y.; Erdil, A.; Ates, Y.; Aslan, M.; et al. Systemic markers of lipid peroxidation and antioxidants in patients with nonalcoholic Fatty liver disease. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2005, 100, 850–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majmundar, A.J.; Wong, W.J.; Simon, M.C. Hypoxia-inducible factors and the response to hypoxic stress. Mol. Cell 2010, 40, 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schofield, C.J.; Ratcliffe, P.J. Oxygen sensing by HIF hydroxylases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunwoodie, S.L. The role of hypoxia in development of the Mammalian embryo. Dev. Cell 2009, 17, 755–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, H.; Ge, J.; Guo, L.; Tahir, R.; Luo, J.; He, K.; Yan, H.; Zhang, X.; Cao, Q.; et al. Mechanism of acclimation to chronic intermittent hypoxia in the gills of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 51, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Spahis, S.; Delvin, E.; Borys, J.M.; Levy, E. Oxidative Stress as a Critical Factor in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Pathogenesis. Antiox. Redox Sign 2017, 26, 519–541. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, D.; Xie, L.; Ke, H.; Zheng, X.; Chen, W. Procyanidin B2 ameliorates free fatty acids-induced hepatic steatosis through regulating TFEB-mediated lysosomal pathway and redox state. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 126, 269–286. [Google Scholar]

- Adjoumani, J.Y.; Wang, K.; Zhou, M.; Liu, W.; Zhang, D. Effect of dietary betaine on growth performance, antioxidant capacity and lipid metabolism in blunt snout bream fed a high-fat diet. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Li, L.; Xia, T.; Wang, L.; Xiao, L.; Ding, N.; Wu, Y.; Lu, K. Oxidative Stress Can Be Attenuated by 4-PBA Caused by High-Fat or Ammonia Nitrogen in Cultured Spotted Seabass: The Mechanism Is Related to Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sariçam, T.; Kircali, B.; Köken, T. Assessment of lipid peroxidation and antioxidant capacity in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Turk. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2005, 16, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Liu, H.; Jiang, J. Evaluation of glycyrrhetinic acid in attenuating adverse effects of a high-fat diet in largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim. Nutr. 2024, 19, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albano, E.; Mottaran, E.; Occhino, G.; Reale, E.; Vidali, M. Review article: Role of oxidative stress in the progression of non-alcoholic steatosis. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 22, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, P.C.; Stuckenholz, C.; Rivera, M.R.; Davison, J.M.; Yao, J.K.; Amsterdam, A.; Sadler, K.C.; Bahary, N. Lack of de novo phosphatidylinositol synthesis leads to endoplasmic reticulum stress and hepatic steatosis in cdipt-deficient zebrafish. Hepatology 2011, 54, 452–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cinaroglu, A.; Gao, C.; Imrie, D.; Sadler, K.C. Activating transcription factor 6 plays protective and pathological roles in steatosis due to endoplasmic reticulum stress in zebrafish. Hepatology 2011, 54, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zulfahmi, I.; El Rahimi, S.A.; Suherman, S.D.; Almunawarah, A.; Sardi, A.; Helmi, K.; Nafis, B.; Perdana, A.W.; Adani, K.H.; Admaja Nasution, I.A.; et al. Acute toxicity of palm oil mill effluent on zebrafish (Danio rerio Hamilton-Buchanan, 1822): Growth performance, behavioral responses and histopathological lesions. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, A. Vaso-dilator axon-reflexes. Q. J. Exp. Physiol. 1913, 6, 339–354. [Google Scholar]

- Calixto, J.B.; Otuki, M.F.; Santos, A.R. Anti-inflammatory compounds of plant origin. Part I. Action on arachidonic acid pathway, nitric oxide and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kappaB). Planta Medica 2003, 69, 973–983. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan, C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature 2002, 420, 846–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Ahluwalia, N.; Albers, R.; Bosco, N.; Bourdet-Sicard, R.; Haller, D.; Holgate, S.T.; Jönsson, L.S.; Latulippe, M.E.; Marcos, A.; et al. A consideration of biomarkers to be used for evaluation of inflammation in human nutritional studies. Br. J. Nutr. 2013, 109, S1–S34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathan, C.; Ding, A. Nonresolving inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 871–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ley, K.; Laudanna, C.; Cybulsky, M.I.; Nourshargh, S. Getting to the site of inflammation: The leukocyte adhesion cascade updated. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singer, A.J.; Clark, R.A. Cutaneous wound healing. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 341, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bordés Gonzalez, R.; Martínez Beltrán, M.; García Olivares, E.; Guisado Barrilao, R. El Proceso Inflamatorio. Rev. Enferm. 1994, 4, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hawiger, J.; Zienkiewicz, J. Decoding inflammation, its causes, genomic responses, and emerging countermeasures. Scand. J. Immunol. 2019, 90, e12812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanden Berghe, T.; Linkermann, A.; Jouan-Lanhouet, S.; Walczak, H.; Vandenabeele, P. Regulated necrosis: The expanding network of non-apoptotic cell death pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 15, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhong, S.; Qu, H.; Xie, Y.; Cao, Z.; Li, Q.; Yang, P.; Varghese, Z.; Moorhead, J.F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Chronic inflammation aggravates metabolic disorders of hepatic fatty acids in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 10222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, M.; Pan, T.T.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, T.T.; Sun, P.; Zhou, F.; Ding, X.Y.; Zhou, C.C. Effects of supplemental dietary L-carnitine and bile acids on growth performance, anti- oxidant and immune ability, histopathological changes and inflammatory response in juvenile black seabream (Acanthopagrus schlegelii) fed high-fat diet. Aquaculture 2019, 504, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Galluzzi, L.; Vitale, I.; Aaronson, S.A.; Abrams, J.M.; Adam, D.; Agostinis, P.; Alnemri, E.S.; Altucci, L.; Amelio, I.; Andrews, D.W.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: Recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2018. Cell Death Dif. 2018, 25, 486–541. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, Y.S.; Seki, E. Toll-like receptors in alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and carcinogenesis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 28, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Linkermann, A. Death and fire-the concept of necroinflammation. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Tsurusaki, S.; Tsuchiya, Y.; Koumura, T.; Nakasone, M.; Sakamoto, T.; Matsuoka, M.; Imai, H.; Yuet-Yin Kok, C.; Okochi, H.; Nakano, H.; et al. Hepatic ferroptosis plays an important role as the trigger for initiating inflammation in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkhouri, N.; Carter-Kent, C.; Feldstein, A.E. Apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 5, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riedl, S.J.; Shi, Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004, 5, 897–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolan, C.J.; Larter, C.Z. Lipotoxicity: Why do saturated fatty acids cause and monounsaturates protect against it? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2009, 24, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.Z.; Berk, M.; McIntyre, T.M.; Feldstein, A.E. Hepatic lipid partitioning and liver damage in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Role of stearoyl-CoA desaturase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 5637–5644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, X.; Wang, S.; Zhao, K.; Li, Y.; Williams, J.A.; Li, T.; Chavan, H.; Krishnamurthy, P.; He, X.C.; Li, L.; et al. Impaired TFEB-Mediated Lysosome Biogenesis and Autophagy Promote Chronic Ethanol-Induced Liver Injury and Steatosis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 865–879.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, S.; Than, T.A.; Zhang, J.; Oo, C.; Min, R.W.M.; Kaplowitz, N. New insights into the role and mechanism of c-Jun-N-terminal kinase signaling in the pathobiology of liver diseases. Hepatology 2018, 67, 2013–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarantino, G.; Caputi, A. JNKs, insulin resistance and inflammation: A possible link between NAFLD and coronary artery disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 17, 3785–3794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.L.; Wang, L.N.; Zhang, D.D.; Liu, W.B.; Xu, W.N. Berberine attenuates oxidative stress and hepatocytes apoptosis via protecting mitochondria in blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala fed high-fat diets. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 43, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.Y.; Dixon, S.J. Mechanisms of ferroptosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2016, 73, 2195–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambright, W.S.; Fonseca, R.S.; Chen, L.; Na, R.; Ran, Q. Ablation of ferroptosis regulator glutathione peroxidase 4 in forebrain neurons promotes cognitive impairment and neurodegeneration. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Schneider, M.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Hammond, V.J.; Herbach, N.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; Eggenhofer, E.; et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, B.; Fisher, R. Temperature influences swimming speed, growth and larval duration in coral reef fish larvae. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2004, 299, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szekeres, P.; Brownscombe, J.; Cull, F.; Danylchuk, A.; Shultz, A.; Suski, C.; Murchie, K.; Cooke, S. Physiological and behavioural consequences of cold shock on bonefish (Albula vulpes) in the Bahamas. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 459, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, H.; Huang, B.; Wagle, M.; Guo, S. Identification of environmental stressors and validation of light preference as a measure of anxiety in larval zebrafish. BMC Neurosci. 2016, 17, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, B.J.; Lewin, H.A.; Goddard, M.E. The future of livestock breeding: Genomic selection for efficiency, reduced emission intensity, and adaptation. Trends Genet. 2013, 29, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robledo, D.; Matika, O.; Hamilton, A.; Houston, R.D. Genome-wide association and genomic selection for resistance to amoebic gill disease in Atlantic salmon. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 2018, 8, 1195–1203. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, R.P.; Lorent, K.; Mañoral-Mobias, R.; Huang, Y.; Gong, W.; Murray, I.V.; Blair, I.A.; Pack, M. TNFalpha-dependent hepatic steatosis and liver degeneration caused by mutation of zebrafish S-adenosylhomocysteine hydrolase. Development 2009, 136, 865–875. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S.W.; Dalton, D.A.; Kramer, S.; Christensen, B.L. Physiological (antioxidant) responses of estuarine fishes to variability in dissolved oxygen. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. Toxicol. Pharmacol. CBP 2001, 130, 289–303. [Google Scholar]

- Bhagat, J.; Ingole, B.S.; Singh, N. Glutathione s-transferase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase, and lipid peroxidation as biomarkers of oxidative stress in snails: A review. Isj-Invertebr. Surviv. J. 2016, 13, 336–349. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H.; Gao, Q.; Dong, S.; Lan, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wen, B. Regulation of dietary glutamine on the growth, intestinal function, immunity and antioxidant capacity of sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus (Selenka). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2016, 50, 56–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf2 signaling in coordinated activation of antioxidant gene expression. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2004, 36, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chambel, S.S.; Santos-Gonçalves, A.; Duarte, T.L. The Dual Role of Nrf2 in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Regulation of Antioxidant Defenses and Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 597134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Yuan, C.; Si, B.; Wang, M.; Da, S.; Bai, L.; Wu, W. Combined effects of ambient particulate matter exposure and a high-fat diet on oxidative stress and steatohepatitis in mice. PloS ONE 2019, 14, e0214680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, G.; Gong, X.; Yang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wang, G.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, H.; Lin, C.; Zhang, J. Effects of extracts from soothing-liver and invigorating-spleen formulas on the injury induced by oxidative stress in the hepatocytes of rats with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease induced by high-fat diet. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2018, 38, 535–547. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, H.; Park, J.; Kim, A.; Kim, N.; Lee, Y.; Kim, B.S.; Vijayan, J.; Lee, M.K.; Park, C.I.; Kim, D.H. Overfeeding-Induced Obesity Could Cause Potential Immuno-Physiological Disorders in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Animals 2020, 10, 1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Li, S.; Niu, H.; Chang, J.; Hu, Z.; Han, Y. Influence of dietary linseed oil as substitution of fish oil on whole fish fatty acid composition, lipid metabolism and oxidative status of juvenile Manchurian trout, Brachymystax lenok. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.F.; Mao, L.Z.; Yu, S.Y.; Huang, J.; Xie, Q.Y.; Hu, M.J.; Mao, L.M. DHA and EPA improve liver IR in HFD-induced IR mice through modulating the gut microbiotas-LPS-liver axis. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 112, 105917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ouyang, H.; Zhu, J. Traditional Chinese medicines and natural products targeting immune cells in the treatment of metabolic-related fatty liver disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1195146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wong, Y.T.; Tang, K.Y.; Kwan, H.Y.; Su, T. Chinese Medicinal Herbs Targeting the Gut-Liver Axis and Adipose Tissue-Liver Axis for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Treatments: The Ancient Wisdom and Modem Science. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 572729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Nie, L.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Q.; Zhou, X. Lingguizhugan Decoction in the Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2025, 25, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebold, K.M.; Kirkwood, J.S.; Taylor, A.W.; Choi, J.; Barton, C.L.; Miller, G.W.; La Du, J.; Jump, D.B.; Stevens, J.F.; Tanguay, R.L.; et al. Novel liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry method shows that vitamin E deficiency depletes arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids in zebrafish (Danio rerio) embryos. Redox Biol. 2013, 2, 105–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, J.; Wasipe, A.; He, J.; Tao, Y.F.; Xu, P.; Bao, J.W.; Chen, D.J.; Zhu, J.H. Dietary vitamin E deficiency inhibits fat metabolism, antioxidant capacity, and immune regulation of inflammatory response in genetically improved farmed tilapia (GIFT, Oreochromis niloticus) fingerlings following Streptococcus iniae infection. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 92, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.C.; Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Wang, J.; Limbu, S.M.; Li, R.X.; Zhou, W.H.; Qiao, F.; Zhang, M.L.; Du, Z.Y. Different effects of two dietary levels of tea polyphenols on the lipid deposition, immunity and antioxidant capacity of juvenile GIFT tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) fed a high-fat diet. Aquaculture 2021, 542, 736896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, V.; Figueroa, F.; González-Pizarro, K.; Jopia, P.; Ibacache-Quiroga, C. Probiotics and Prebiotics as a Strategy for Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, a Narrative Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashimada, M.; Honda, M. Effect of Microbiome on Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and the Role of Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Biogenics. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.Z.; Yang, G.H.; Liu, Y.L. Study on formation and prevention of fatty liver in blunt snout bream. Fish. Sci. Technol. Inf. 1992, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Yan, M.; Luo, Z.; Luo, F.; Feng, L.; Jiang, W.; Wu, P.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; et al. Vitamin D3 activates the innate immune response and xenophagy against Nocardia seriolae through the VD receptor in liver of largemouth bass (Microperus salmoides). Aquaculture 2024, 578, 740008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxton, R.A.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR Signaling in Growth, Metabolism, and Disease. Cell 2017, 168, 960–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichhart, T.; Hengstschläger, M.; Linke, M. Regulation of innate immune cell function by mTOR. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 15, 599–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Xie, X.; Zhang, C.; Zulfahmi, I.; Mbokane, E.; Cao, Q. Fatty Liver in Fish: Metabolic Drivers, Molecular Pathways and Physiological Solutions. Animals 2026, 16, 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020236

Xie X, Zhang C, Zulfahmi I, Mbokane E, Cao Q. Fatty Liver in Fish: Metabolic Drivers, Molecular Pathways and Physiological Solutions. Animals. 2026; 16(2):236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020236

Chicago/Turabian StyleXie, Xiyu, Chaoyang Zhang, Ilham Zulfahmi, Esau Mbokane, and Quanquan Cao. 2026. "Fatty Liver in Fish: Metabolic Drivers, Molecular Pathways and Physiological Solutions" Animals 16, no. 2: 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020236

APA StyleXie, X., Zhang, C., Zulfahmi, I., Mbokane, E., & Cao, Q. (2026). Fatty Liver in Fish: Metabolic Drivers, Molecular Pathways and Physiological Solutions. Animals, 16(2), 236. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020236