Non-Invasive Assessment of Adrenal Activity in the Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum in Field and Laboratory Conditions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Housing

2.2. Blood Collection and Stress Markers

2.3. Feces Collection

2.4. Enzyme Immunoassay Validation for FGCs

2.5. Extraction of FGC Metabolites and Enzyme Immunoassay

2.6. Behavior

2.7. Statistical Procedures

3. Results

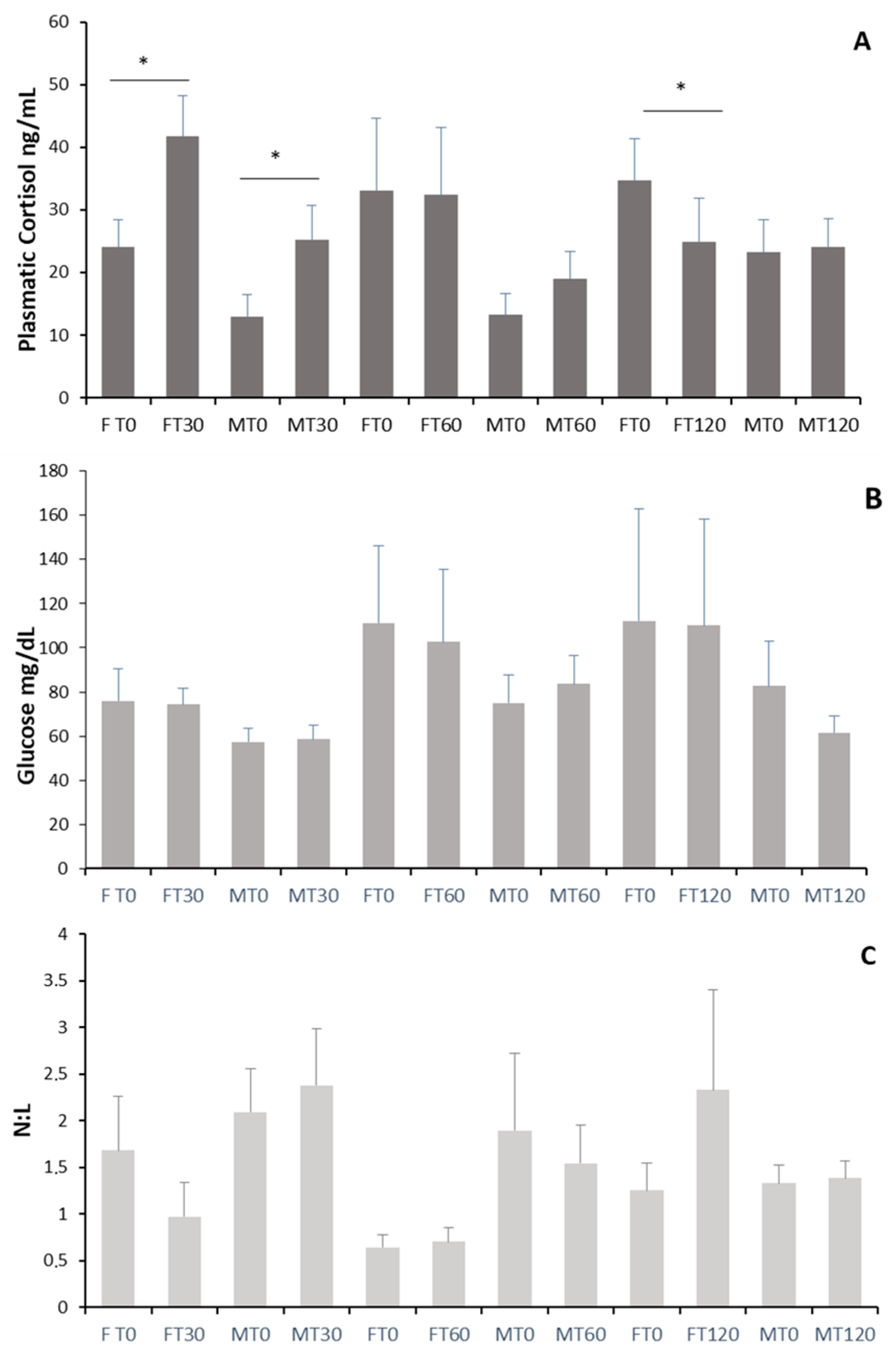

3.1. Stress Response to Blood Collection

3.2. Enzyme Immunoassay Validation for FGCs

3.2.1. Effect of Capture, Transportation and Captivity

3.2.2. ACTH Challenge Test

3.2.3. Immobilization

3.2.4. Sample Stability

3.2.5. Sex and Reproductive Seasonality

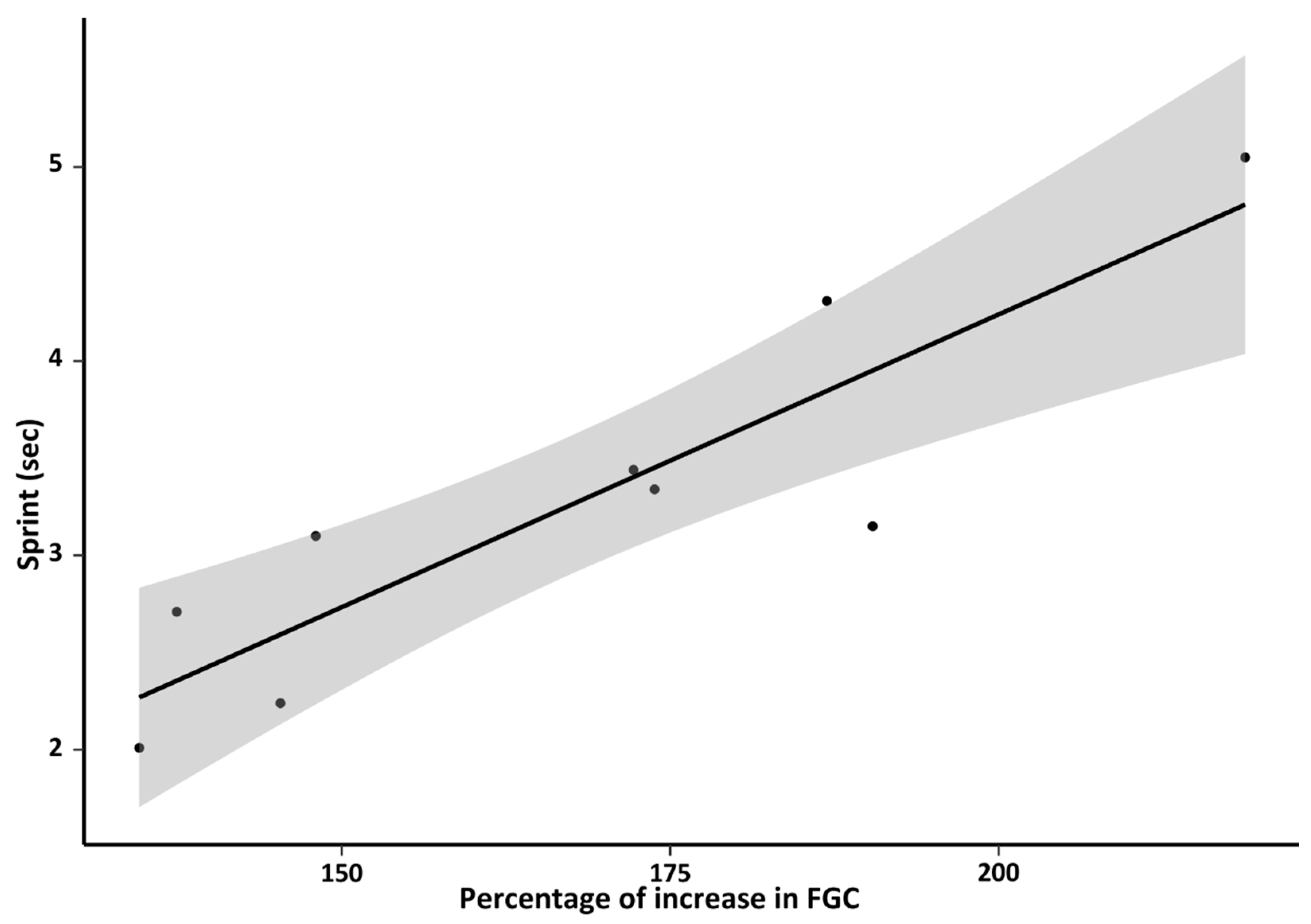

3.2.6. Behavior

4. Discussion

4.1. Stress Response to Blood Collection

4.2. Enzyme Immunoassay Validation for FGCs

4.2.1. Capture, Transportation and Captivity

4.2.2. ACTH Challenge Test

4.2.3. Immobilization

4.2.4. Sample Stability

4.2.5. Sex and Reproduction

4.2.6. Behavior and Adrenal Activity

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis |

| SAM | Sympathetic–adrenal–medullary axis |

| ACTH | Adreconocorticotropic hormone |

| GCs | Glucocorticoids |

| FGCs | Fecal metabolite of glucocorticoids |

| N/L | Neutrophils/ Lymphocytes rate |

Appendix A

References

- Armario, A. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis: What can it tell us about stressors? CNS Neurol. Disord.—Drug Targets 2006, 5, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, B.; Fletcher, Q.E.; Boonstra, R.; Sheriff, M.J. Measures of physiological stress: A transparent or opaque window into the status, management and conservation of species? Conserv. Physiol. 2014, 2, cou023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, J.C.; Breuner, C.; Jacobs, J.; Lynn, S.; Maney, D.; Ramenofsky, M.; Richardson, R. Ecological bases of hormone-behavior interactions: The “Emergency Life History Stage”. Am. Zool. 1998, 38, 191–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricklefs, R.E.; Wikelski, M. The physiology-life history nexus. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2002, 17, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, D.M.; Kramer, K.M. Stress in free-ranging mammals: Integrating physiology, ecology, and natural history. J. Mammal. 2005, 86, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingfield, J.C. The concept of allostasis: Coping with a capricious environment. J. Mammal. 2005, 86, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M.; Wikelski, M. Corticosterone levels predict survival probabilities of Galápagos marine iguanas during El Niño events. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 7366–7370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M.; Dickens, M.J.; Cyr, N.E. The reactive scope model: A new model integrating homeostasis, allostasis, and stress. Horm. Behav. 2009, 55, 375–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapolsky, R.M.; Romero, L.M.; Munck, A.U. How do glucocorticoids influence stress responses? integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr. Rev. 2000, 21, 55–89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dhabhar, F.S. Effects of stress on immune function: The good, the bad, and the beautiful. Imm. Res. 2014, 58, 193–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charbonnel, N.; Chaval, Y.; Berthier, K.; Deter, J.; Morand, S.; Palme, R.; Cosson, J.F. Stress and demographic decline: A potential effect mediated by impairment of reproduction and immune function in cyclic vole populations. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2008, 81, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palme, R. Monitoring stress hormone metabolites as a useful, non-invasive tool for welfare assessment in farm animals. Anim. Welf. 2012, 21, 331–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaer, M.C.; Čebulj-Kadunc, N.; Snoj, T. Stress in wildlife: Comparison of the stress response among domestic, captive, and free-ranging animals. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1167016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, U.K.; Mikolajczak, L.; Fefferman, N.; Romero, L.M. Neophobia, but not perch hopping, is sensitive to long-term chronic stress intensity. J. Exp. Zool. A 2023, 339, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolhaas, J.M.; Korte, S.M.; De Boer, S.F.; Van Der Vegt, B.J.; Van Reenen, C.G.; Hopster, H.; De Jong, I.C.; Ruis, M.A.W.; Blokhuis, H.J. Coping styles in animals: Current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1999, 23, 925–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, R. Equipped for life: The adaptive role of the stress axis in male mammals. J. Mammal. 2005, 86, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, M.J.; Dantzer, B.; Delehanty, B.; Palme, R.; Boonstra, R. Measuring stress in wildlife: Techniques for quantifying glucocorticoids. Oecologia 2011, 166, 869–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, J.M.; Austad, S.N. Fecal glucocorticoids: A noninvasive method of measuring adrenal activity in wild and captive rodents. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2000, 73, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palme, R. Measuring fecal steroids—Guidelines for practical application. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1046, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palme, R. Non-invasive measurement of glucocorticoids: Advances and problems. Physiol. Behav. 2019, 199, 229–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soulsbury, C.D.; Gray, H.E.; Smith, L.M.; Braithwaite, V.; Cotter, S.C.; Elwood, R.W.; Wilkinson, A.; Collins, L.M. The welfare and ethics of research involving wild animals: A primer. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2020, 11, 1164–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calisi, R.M.; Bentley, G.E. Lab and field experiments: Are they the same animal? Horm. Behav. 2009, 56, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möstl, E.; Messmann, S.; Bagu, E.; Robia, C.; Palme, R. Measurement of glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations in faeces of domestic livestock. J. Vet. Med. 1999, 46, 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Palme, R.; Rettenbacher, S.; Touma, C.; El-Bahr, S.M.; Möstl, E. Stress hormones in mammals and birds: Comparative aspects regarding metabolism, excretion and noninvasive measurement in fecal samples. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1040, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheriff, M.J.; Krebs, C.J.; Boonstra, R. Assessing stress in animal populations: Do fecal and plasma glucocorticoids tell the same story? Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 166, 614–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touma, C.; Palme, R. Measuring fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in mammals and birds: The importance of validation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1046, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, P.D.; Mooney, S.J.; Bosson, C.; Toor, I.; Palme, R.; Holmes, M.M.; Boonstra, R. The stress of being alone: Removal from the colony, but not social subordination, increases cortisol in eusocial naked mole-rats. Horm. Behav. 2020, 121, 104720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millspaugh, J.J.; Washburn, B.E. Use of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite measures in conservation biology research: Considerations for application and interpretation. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2004, 138, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lafferty, D.J.R.; Zimova, M.; Clontz, L.; Hackländer, K.; Mills, L.S. Noninvasive measures of physiological stress are confounded by exposure. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berl, J.L.; Voorhees, M.W.; Wu, J.W.; Flaherty, E.A.; Swihart, R.K. Collection of blood from wild-caught mice (Peromyscus) via submandibular venipuncture. Wild. Soc. Bull. 2017, 41, 816–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, X.; Billy, G.; Lakusic, M. Puncture versus capture: Which stresses animals the most? J. Comp. Physiol. B 2020, 190, 341–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenuto, R.; Malizia, A.I.; Busch, C. Sexual size dimorphism, relative testes size and mating system in two populations of Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia: Octodontidae). J. Nat. Hist. 1999, 33, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, C.; Malizia, A.I.; Scaglia, O.A.; Reig, O.A. Spatial distribution and attributes of a population of Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia: Octodontidae). J. Mammal. 1989, 70, 204–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antinuchi, D.; Busch, C. Burrow structure in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. Mamm. Biol. 1992, 57, 163–168. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, C.; Antinuchi, D.; Del Valle, J.; Kittlein, M.; Malizia, A.; Vassallo, A.; Zenuto, R. Population ecology of subterranean rodents. In Life Underground: The Biology of Subterranean Rodents; Lacey, E.A., Patton, J.L., Cameron, G.N., Eds.; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2000; pp. 183–226. [Google Scholar]

- Vera, F.; Antenucci, C.D.; Zenuto, R. Cortisol and corticosterone exhibit different seasonal variation and responses to acute stress and captivity in tuco-tucos (Ctenomys talarum). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 170, 550–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Zenuto, R.; Antenucci, C.D. Seasonal variations in plasma cortisol, testosterone, progesterone and leukocyte profiles in a wild population of tuco-tucos. J. Zool. 2013, 289, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Zenuto, R.; Antenucci, C.D. Differential responses of cortisol and corticosterone to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) in a subterranean rodent (Ctenomys talarum). J. Exp. Zool. A 2012, 317, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Antenucci, C.D.; Zenuto, R.R. Different regulation of cortisol and corticosterone in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum: Responses to dexamethasone, angiotensin II, potassium, and diet. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2019, 273, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brachetta, V.; Schleich, C.E.; Zenuto, R.R. Differential antipredatory responses in the tuco-tuco (Ctenomys talarum) in relation to endogenous and exogenous changes in glucocorticoids. J. Comp. Physiol. A 2020, 206, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizo, M.C.; Zenuto, R.R.; Luna, F.; Cutrera, A.P. Varying intensity of simulated infection partially affects the magnitude of the acute-phase immune response in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. J. Exp. Zool. A 2023, 339, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanjul, M.S.; Cutrera, A.P.; Luna, F.; Zenuto, R.R. Individual differences in behaviour are related to metabolism, stress response, testosterone, and immunity in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. Behav. Proc. 2023, 212, 104945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanjul, M.S.; Cutrera, A.P.; Luna, F.; Schleich, C.E.; Brachetta, V.; Antenucci, C.D.; Zenuto, R.R. Ecological Physiology and Behavior in the Genus Ctenomys. In Tuco-Tucos. An Evolutionary Approach to the Diversity of a Neotropical Subterranean Rodent; Freitas, T.R.O., Gonçalves, G.L., Maestri, R., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone, C.P.; Reina, R.D.; Lill, A. Interpreting indices of physiological stress in free-living vertebrates: A review. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2012, 182, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Zenuto, R.; Antinuchi, C.D. Decreased glucose tolerance but normal blood glucose levels in the field in the caviomorph rodent Ctenomys talarum: The role of stress and physical activity. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2008, 151, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schleich, C.E.; Zenuto, R.R.; Cutrera, A.P. Immune challenge but not dietary restriction affects spatial learning in the wild subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. Physiol. Behav. 2015, 139, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, A.K.; Maney, D.L.; Maerz, J.C. The use of leukocyte profiles to measure stress in vertebrates: A review for ecologists. Funct. Ecol. 2008, 22, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.K.; Maney, D.L. The use of glucocorticoid hormones or leucocyte profiles to measure stress in vertebrates: What’s the difference? Methods Ecol. Evol. 2018, 9, 1556–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, M.; Hickman, D. Evaluation of the neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio as a measure of distress in rats. Lab. Anim. 2014, 43, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, N.S.; Zenuto, R.R.; Busch, C. Nutritional responses to different diet quality in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum (tuco-tucos). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2007, 147, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perissinotti, P.P.; Antinuchi, C.D.; Zenuto, R.R.; Luna, F. Effect of diet quality and soil hardness on basal metabolic rate in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2009, 154, 298–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna, F.; Antinuchi, C.D.; Busch, C. Ritmos de actividad locomotora y uso de las cuevas en condiciones seminaturales en Ctenomys talarum (Rodentia, Octodontidae). Rev. Chil. Hist Nat. 2000, 73, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrera, A.P.; Antinuchi, C.D.; Mora, M.S.; Vassallo, A.I. Home-Range and Activity Patterns of the South American Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum. J. Mammal. 2006, 87, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St Juliana, J.R.; Khokhlova, I.S.; Wielebnowski, N.; Kotler, B.P.; Krasnov, B.R. Ectoparasitism and stress hormones: Strategy of host exploitation, common host–parasite history and energetics matter. J. Anim. Ecol. 2014, 83, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touma, C.; Sachser, N.; Mostl, E.; Palme, R. Effects of sex and time of day on metabolism and excretion of corticosterone in urine and feces of mice. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2003, 130, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Ross, X.; Taha, H.B.; Press, E.; Rhone, S.; Blumstein, D.T. Validating an immunoassay to measure fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in yellow-bellied marmots. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A 2024, 298, 111738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro-Castilla, Á.; Garrido, M.; Hawlena, H.; Barja, I. Non-invasive monitoring of adrenocortical activity in three sympatric desert gerbil species. Animals 2021, 11, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, B.; McAdam, A.G.; Palme, R.; Fletcher, Q.E.; Boutin, S.; Humphries, M.M.; Boonstra, R. Fecal cortisol metabolite levels in free-ranging North American red squirrels: Assay validation and the effects of reproductive condition. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2010, 167, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleftheriou, A.; Palme, R.; Boonstra, R. Assessment of the stress response in North American deermice: Laboratory and field validation of two enzyme immunoassays for fecal corticosterone metabolites. Animals 2020, 10, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiglio, P.O.; Pelletier, F.; Palme, R.; Garant, D.; Humphries, M.; Reale, D.; Boonstra, R. Non-invasive monitoring of fecal cortisol metabolites in the Eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus): Validation and comparison of two enzyme immunoassays. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2012, 85, 183–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotjan, H.E.; Keel, B.A. Data interpretation and quality control. In Immunoassay; Diamandis, E.P., Christopoulos, T.K., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1996; pp. 51–95. [Google Scholar]

- Palme, R.; Touma, C.; Arias, N.; Dominchin, M.F.; Lepschy, M. Steroid extraction: Get the best out of fecal samples. Vet. Med. Aust. 2013, 100, 238–246. [Google Scholar]

- Fanjul, M.S.; Zenuto, R.R. Personality underground: Evidence of behavioral types in the solitary subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. PeerJ 2020, 8, e8490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Réale, D.; Reader, S.M.; Sol, D.; McDougall, P.T.; Dingemanse, N.J. Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution. Biol. Rev. 2007, 82, 291–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piquet, J.C.; López-Darias, M.; van der Marel, A.; Nogales, M.; Waterman, J. Unraveling behavioral and pace-of-life syndromes in a reduced parasite and predation pressure context: Personality and survival of the Barbary ground squirrel. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2018, 72, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnani, P.; Careau, V. The fast and the curious III: Speed, endurance, activity, and exploration in mice. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2023, 77, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, J.; Bates, D.; DebRoy, S.; Sarkar, D.; R Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Pinheiro, J.C.; Bates, D.M. Mixed-Effects Models in Sand S-PLUS; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 1989, 43, 223–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaherty, E.A.; Noakes, A.G.; Ben-David, M. Saphenous venipuncture for field collection of blood from least chipmunks. Wild. Soc. Bull. 2014, 38, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M. Physiological stress in ecology: Lessons from biomedical research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2004, 19, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, C.M.; Skaff, N.K.; Bernard, A.B.; Trevino, J.M.; Ho, J.M.; Romero, L.M.; Ebensperger, L.A.; Hayes, L.D. Habitat type influences endocrine stress response in the degu (Octodon degus). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 186, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammond, T.T.; Vo, M.; Burton, C.T.; Surber, L.L.; Lacey, E.A.; Smith, J.E. Physiological and behavioral responses to anthropogenic stressors in a human-tolerant mammal. J. Mammal. 2019, 100, 1928–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künzl, C.; Sachser, N. The behavioral endocrinology of domestication: A comparison between the domestic guinea pig (Cavia aperea f. porcellus) and its wild ancestor, the cavy (Cavia aperea). Horm. Behav. 1999, 35, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, J.F.; Ryan, C.P.; Enright, C.; Gardiner, L.E.; Skyner, L.J.; Berkvens, C.N.; Anderson, W.G. Validation of a radioimmunoassay-based fecal corticosteroid assay for Richardson’s ground squirrels Urocitellus richardsonii and behavioural correlates of stress. Curr. Zool. 2014, 60, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, M.; Monarca, R.I.; Aparício, G.; Mathias, M.D.L.; Tapisso, J.T.; von Merten, S. Physiological and behavioural adjustment of a wild rodent to laboratory conditions. Physiol. Behav. 2023, 273, 114385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodruff, J.A.; Lacey, E.A.; Bentley, G. Contrasting fecal corticosterone metabolite levels in captive and free-living colonial tuco-tucos (Ctenomys sociabilis). J. Exp. Zool. A 2010, 313, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickens, M.J.; Romero, L.M. A consensus endocrine profile for chronically stressed wild animals does not exist. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2013, 191, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, L.M.; Beattie, U.K. Common myths of glucocorticoid function in ecology and conservation. J. Exp. Zool. A 2021, 337, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, C.P.; Romero, L.M. Chronic captivity stress in wild animals is highly species-specific. Conserv. Physiol. 2019, 7, coz093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möstl, E.; Palme, R. Hormones as indicators of stress. Dom. Anim. Endocrinol. 2002, 23, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalliokoski, O.; Teilmann, A.C.; Abelson, K.S.P.; Hau, J. The distorting effect of varying diets on fecal glucocorticoid measurements as indicators of stress: A cautionary demonstration using laboratory mice. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2015, 211, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauteux, D.; Gauthier, G.; Berteaux, D.; Bosson, C.; Palme, R.; Boonstra, R. Assessing stress in arctic lemmings: Fecal metabolite levels reflect plasma free corticosterone levels. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2017, 90, 370–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Gamboa, M.; Gonzalez, S.; Hayes, L.D.; Ebensperger, L.A. Validation of a radioimmunoassay for measuring fecal cortisol metabolites in the hystricomorph rodent, Octodon degus. J. Exp. Zool. A 2009, 311, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipari, S.; Ylönen, H.; Palme, R. Excretion and measurement of corticosterone and testosterone metabolites in bank voles (Myodes glareolus). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2017, 243, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepschy, M.; Touma, C.; Hruby, R.; Palme, R. Non-invasive measurement of adrenocortical activity in male and female rats. Lab. Anim. 2007, 41, 372–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vobrubová, B.; Fraňková, M.; Štolhoferová, I.; Kaftanová, B.; Rudolfová, V.; Chomik, A.; Chumová, P.; Stejskal, V.; Palme, R.; Frynta, D. Relationship between exploratory activity and adrenocortical activity in the black rat (Rattus rattus). J. Exp. Zool. A 2021, 335, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelini, M.O.; Otta, E.; Yamakita, C.; Palme, R. Sex differences in the excretion of fecal glucocorticoid metabolites in the Syrian hamster. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2010, 180, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, S.L.; Irian, C.G.; Bentley, G.E.; Lacey, E.A. Sex, not social behavior, predicts fecal glucocorticoid metabolite concentrations in a facultatively social rodent, the highland tuco-tuco (Ctenomys opimus). Horm. Behav. 2022, 141, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, J.H.; Du, S.Y.; Wu, Y.; Cao, Y.F.; Nie, X.H.; He, H.; You, Z.B. Maternal effects and population regulation: Maternal density-induced reproduction suppression impairs offspring capacity in response to immediate environment in root voles Microtus oeconomus. J. Anim. Ecol. 2015, 84, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, C.M.; Ebensperger, L.A.; León, C.; Ramírez-Estrada, J.; Hayes, L.D.; Romero, L.M. Postnatal development of the degu (Octodon degus) endocrine stress response is affected by maternal care. J. Exp. Zool. A 2016, 325, 304–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateo, J.M. Ecological and hormonal correlates of antipredator behavior in adult Belding’s ground squirrels (Spermophilus beldingi). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007, 62, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goymann, W. On the use of non-invasive hormone research in uncontrolled, natural environments: The problem with sex, diet, metabolic rate and the individual. Methods Ecol Evol. 2012, 3, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barja, I.; Escribano-Ávila, G.; Lara-Romero, C.; Virgós, E.; Benito, J.; Rafart, E. Non-invasive monitoring of adrenocortical activity in European badgers (Meles meles) and effects of sample collection and storage on faecal cortisol metabolite concentrations. An. Biol. 2012, 62, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donini, V.; Iacona, E.; Pedrotti, L.; Macho-Maschler, S.; Palme, R.; Corlatti, L. Temporal stability of fecal cortisol metabolites in mountain-dwelling ungulates. Sci. Nat. 2022, 109, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arias, N.; Requena, M.; Palme, R. Measuring faecal glucocorticoid metabolites as a non-invasive tool for monitoring adrenocortical activity in South American camelids. Anim. Welf. 2013, 22, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möstl, E.; Rettenbacher, S.; Palme, R. Measurement of corticosterone metabolites in birds’ droppings: An analytical approach. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1046, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lexen, E.; El-Bahr, S.; Sommerferfeld-Stur, I.; Palme, R.; Möstl, E. Monitoring the adrenocortical response to disturbances in sheep by measuring glucocorticoid metabolites in the faeces. Vet. Med. Aust. 2008, 95, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Romero, L.M. Seasonal changes in plasma glucocorticoid concentrations in free living vertebrates. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2002, 128, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenuto, R.; Vassallo, A.; Busch, C. Comportamiento social y reproductivo del roedor subterráneo Ctenomys talarum en condiciones de semicautiverio. Rev. Chil. Hist. Nat. 2002, 75, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenuto, R.; Antinuchi, C.D.; Busch, C. Bioenergetics of reproduction and strategy of pup development in the subterranean rodent Ctenomys talarum. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 2002, 75, 469–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, F.; Zenuto, R.; Antenucci, C.D. Expanding the actions of cortisol and corticosterone in wild vertebrates: A necessary step to overcome the emerging challenges. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2017, 246, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dantzer, B.; Santicchia, F.; van Kesteren, F.; Palme, R.; Martinoli, A.; Wauters, L.A. Measurement of fecal glucocorticoid metabolite levels in Eurasian red squirrels (Sciurus vulgaris): Effects of captivity, sex, reproductive condition, and season. J. Mammal. 2016, 97, 1385–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeder, D.M.; Kosteczko, N.S.; Kunz, T.H.; Widmaier, E.P. Changes in baseline and stress-induced glucocorticoid levels during the active period in free-ranging male and female little brown myotis, Myotis lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2004, 136, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westrick, S.E.; van Kesteren, F.; Palme, R.; Lane, J.E.; Bputin, S.; McAdam, A.G.; Dantzer, B. Stress activity is not predictive of coping style in North American red squirrels. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2019, 73, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Pasquaretta, C.; Carere, C.; Cavallone, E.; von Hardenberg, A.; Réale, D. Testing for the presence of coping styles in a wild mammal. An. Behav. 2013, 85, 1385–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clary, D.; Skyner, L.J.; Ryan, C.P.; Gardiner, L.E.; Anderson, W.G.; Hare, J.F. Shyness-boldness, but not exploration, predicts glucocorticoid stress response in Richardson’s ground squirrels (Urocitellus richardsonii). Ethology 2014, 120, 1101–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raulo, A.; Dantzer, B. Associations between glucocorticoids and sociality across a continuum of vertebrate social behavior. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 7697–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, D. The race goes to the swift: Fitness consequences of variation in sprint performance in juvenile lizards. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2004, 6, 63–75. [Google Scholar]

- Sevenello, M.; Luna, P.; De La Rosa-Perea, D.; Guevara-Fiore, P. Direct and correlated responses to artificial selection on foraging in Drosophila. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2023, 77, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husak, J.F. Does Survival Depend on How Fast You Can Run or How Fast You Do Run? Funct. Ecol. 2006, 20, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, R.S.; Pavlic, T.P.; Wheatley, R.; Niehaus, A.C.; Levy, O. Modeling escape success in terrestrial predator–prey interactions. Integr. Comp. Biol. 2020, 60, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husak, J.F.; Fox, S.F.; Lovern, M.B.; van der Bussche, R.A. Faster lizards sire more offspring: Sexual selection on whole-animal performance. Evolution 2006, 60, 2122–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C.C.; Husak, J.F. Locomotor performance and sexual selection: Individual variation in sprint speed of collared lizards (Crotaphytus collaris). Copeia 2006, 2, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clutton-Brock, T. Social evolution in mammals. Science 2021, 373, eabc9699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olivier, C.A.; Schradin, C.; Makuya, L. Global change and conservation of solitary mammals. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 906446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikes, R.S. The Animal Care and Use Committee of the American Society of Mammalogists Guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists for the use of wild mammals in research and education. J. Mammal. 2016, 97, 663–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zenuto, R.; Brachetta, V.; Carrizo, M.C.; Fanjul, M.S.; Schleich, C.E. Non-Invasive Assessment of Adrenal Activity in the Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum in Field and Laboratory Conditions. Animals 2026, 16, 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020234

Zenuto R, Brachetta V, Carrizo MC, Fanjul MS, Schleich CE. Non-Invasive Assessment of Adrenal Activity in the Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum in Field and Laboratory Conditions. Animals. 2026; 16(2):234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020234

Chicago/Turabian StyleZenuto, Roxana, Valentina Brachetta, María Celina Carrizo, María Sol Fanjul, and Cristian Eric Schleich. 2026. "Non-Invasive Assessment of Adrenal Activity in the Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum in Field and Laboratory Conditions" Animals 16, no. 2: 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020234

APA StyleZenuto, R., Brachetta, V., Carrizo, M. C., Fanjul, M. S., & Schleich, C. E. (2026). Non-Invasive Assessment of Adrenal Activity in the Subterranean Rodent Ctenomys talarum in Field and Laboratory Conditions. Animals, 16(2), 234. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020234