The Welfare Impact of Heat Stress in South American Beef Cattle and the Cost-Effectiveness of Shade Provision

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Climate Data and Heat Stress Assessment

2.2. Chronic Heat Stress: Annual Thermal Load

2.3. Heat Stress Scenarios

2.4. Welfare Impact Quantification

2.5. Shade Mitigation Modeling

2.6. Economic Analysis

3. Results

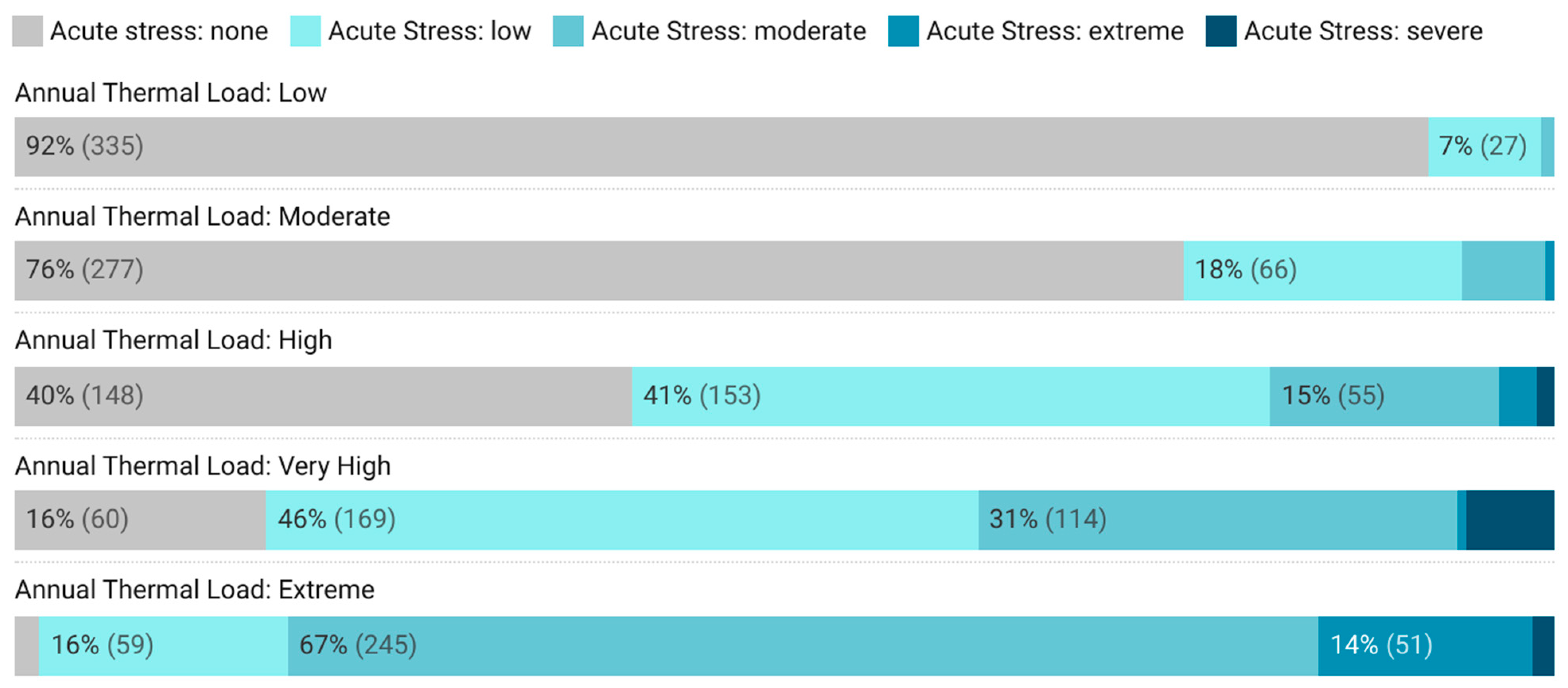

3.1. Heat Stress Exposure Patterns

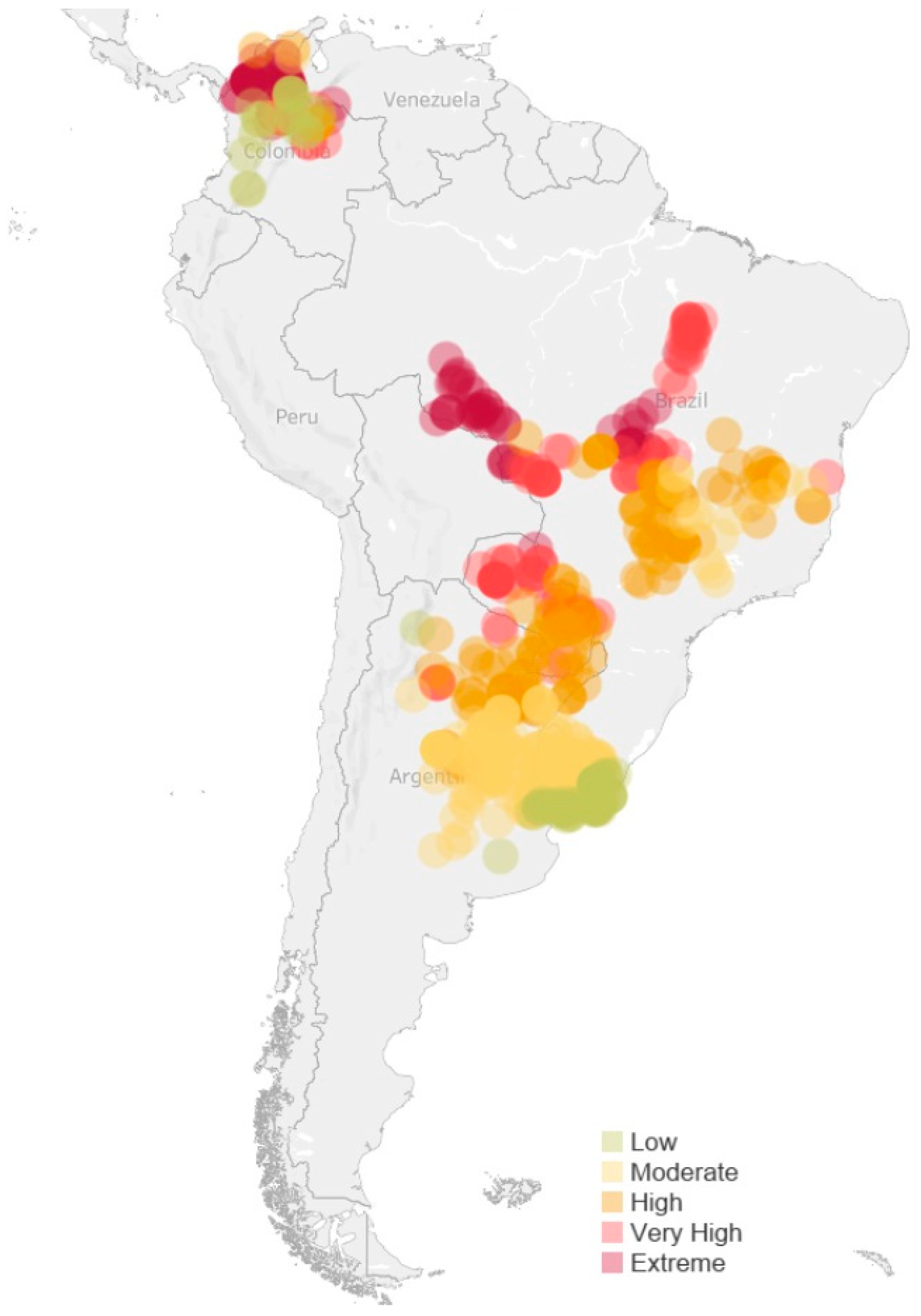

3.2. Geographic Distribution of Thermal Risk

3.3. Quantification of Welfare Impacts

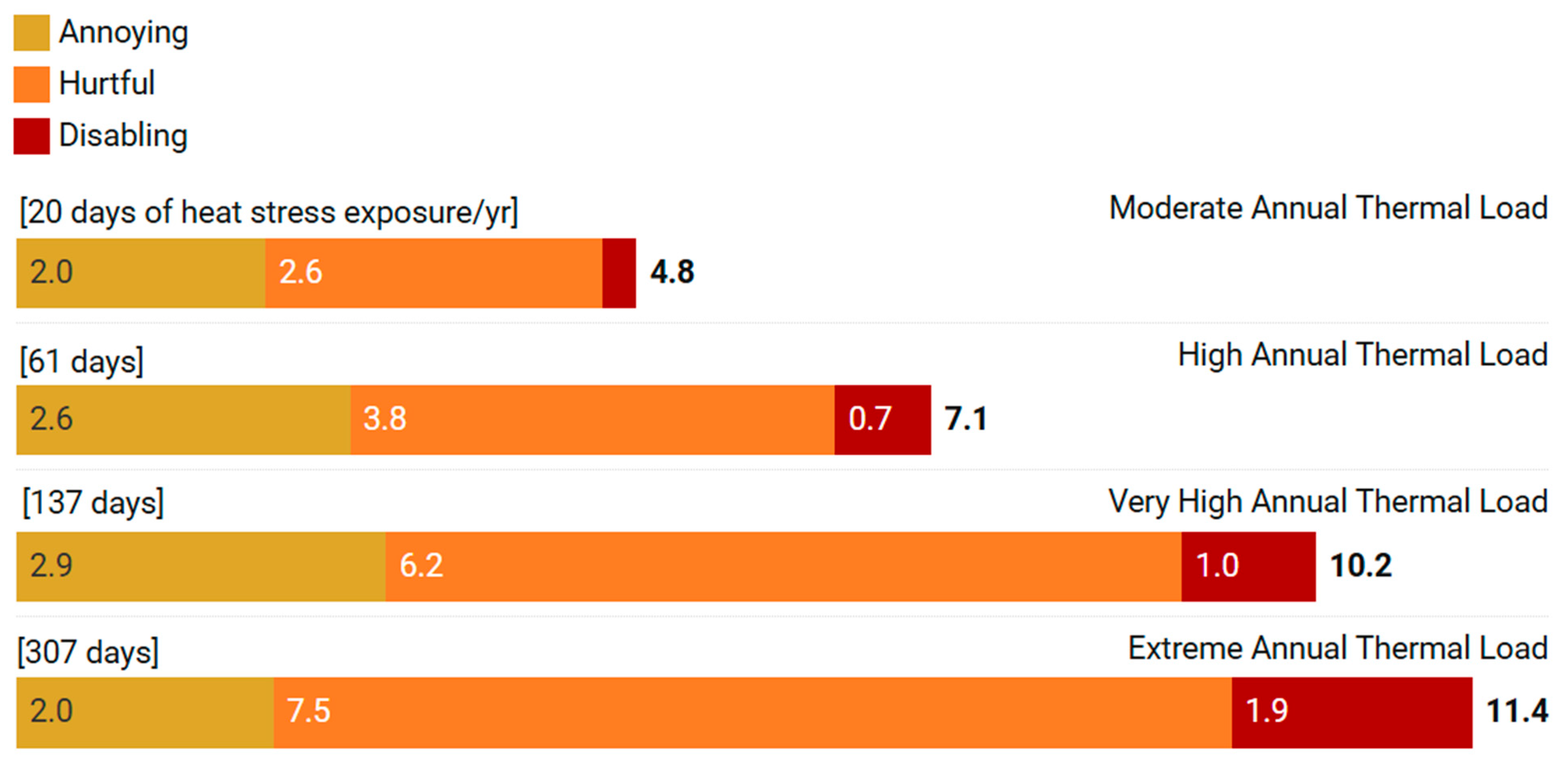

3.3.1. Duration of Thermal Discomfort from Daily Heat Stress Episodes

3.3.2. Intensity of Thermal Discomfort from Heat Stress Episodes

3.3.3. Cumulative Time in Thermal Discomfort

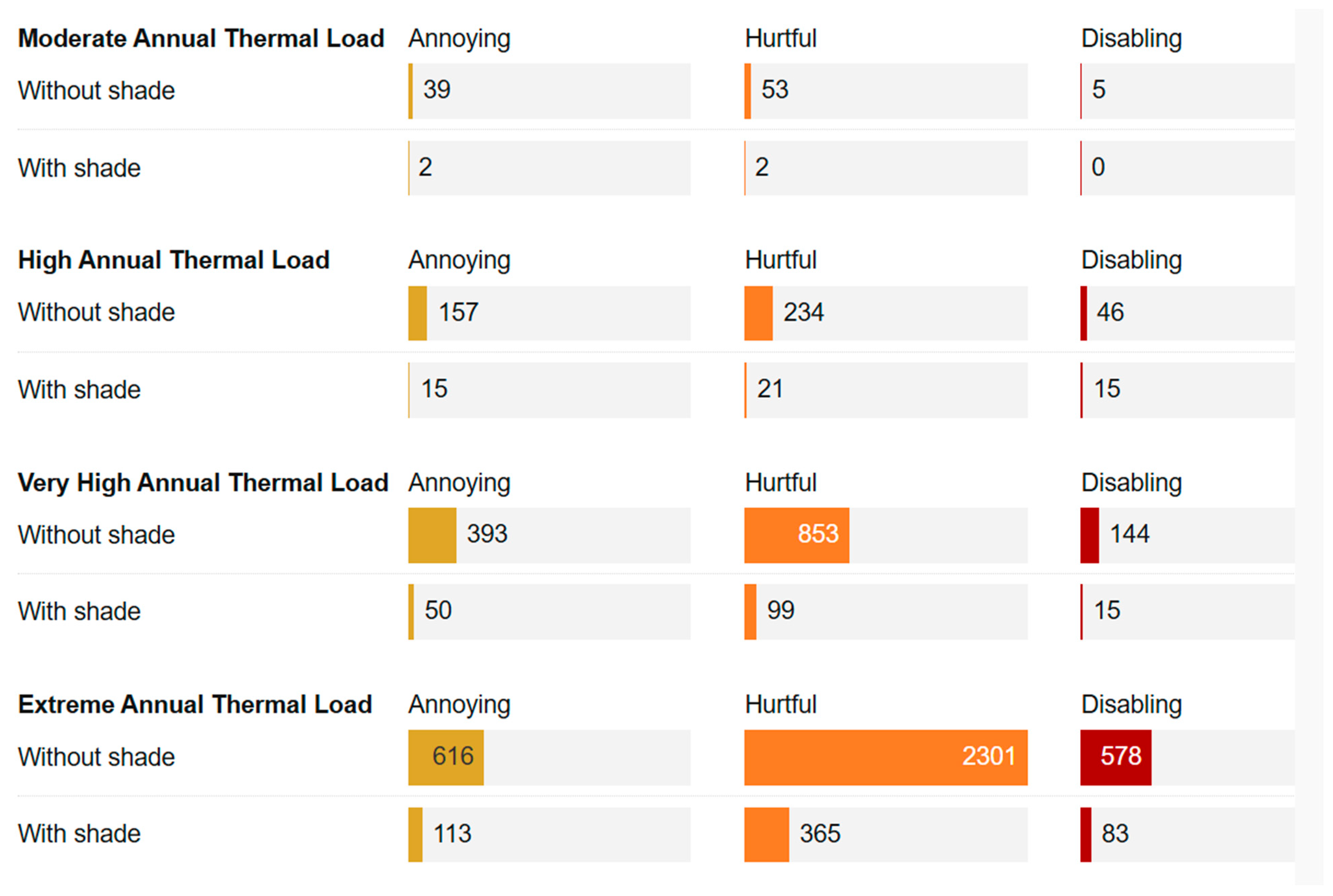

3.3.4. Welfare Impact and Cost-Effectiveness of Shading

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thornton, P.; Nelson, G.; Mayberry, D.; Herrero, M. Impacts of heat stress on global cattle production during the 21st century: A modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 2022, 6, e192–e201. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, M.; Vaidya, M.; Kumar, S.; Singh, G.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Chauhan, S.S. Heat stress: A major threat to ruminant reproduction and mitigating strategies. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2025, 69, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Osei-Amponsah, R.; Clarke, I.; Sejian, V.; Warner, R.; Dunshea, F.R. Impact of heat stress on ruminant livestock production and meat quality, and strategies for amelioration. Anim. Front. 2023, 13, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvatte, N. Índices Microclimáticos e Indicadores de Estresse Térmico em Bovinos de Corte. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia, Brazil, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mitlohener, M.; Laube, R.B. Chronobiological indicators of heat stress in Bos indicus cattle in the tropics. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 2003, 2, 654–659. [Google Scholar]

- Moura, G.A.B.; Costa, C.C.M.; Fonsêca, V.F.C.; Wijffels, G.; Castro, P.A.; Neto, M.C.; Maia, A.S.C. Are crossbred cattle (F1, Bos indicus × Bos taurus) thermally different from purebred Bos indicus cattle under moderate conditions? Livest. Sci. 2021, 246, 104457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aurambout, J.-P.; Benke, K.K.; O’Leary, G.J. Accumulative heat stress in ruminants at the regional scale under changing environmental conditions. Environments 2024, 11, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, R.; Arablouei, R.; McCosker, K.; Bishop-Hurley, G.; Bagnall, N.; Hayes, B.; Reverter, A.; Ingham, A.; Bernhardt, H. Insights into thermal stress effects on performance and behavior of grazing cattle via multimodal sensor monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 27941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruselli, P.S.; Abreu, L.A.; Menchaca, A.; Bó, G.A. The future of beef production in South America. Theriogenology 2025, 231, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Melo Costa, C.C.; Maia, A.S.C.; Brown-Brandl, T.M.; Neto, M.C.; de França Carvalho Fonsêca, V. Thermal equilibrium of Nellore cattle in tropical conditions: An investigation of circadian pattern. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 74, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, C.C.N.; Fonseca, V.F.C.; Fuller, A.; de Melo Costa, C.C.; Beletti, M.E.; Nascimento, M.R.B.M. Can Bos indicus cattle breeds be discriminated by seasonal changes in sweat gland traits? J. Therm. Biol. 2019, 86, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Barreto, A.; Jacintho, M.A.C.; Barioni, W., Jr.; Pereira, A.M.F.; Costa, L.N.; Brandão, F.Z.; Romanello, N.; Azevedo, G.N.; Garcia, A.R. Adaptive integumentary features of beef cattle raised on afforested or non-shaded tropical pastures. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, R.G.; Guilhermino, M.M.; de Morais, D.A.E.F. Thermal radiation absorbed by dairy cows in pasture. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2010, 54, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mader, T.L.; Johnson, L.J.; Gaughan, J.B. A comprehensive index for assessing environmental stress in animals. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 2153–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Pierre, N.R.; Cobanov, B.; Schnitkey, G. Economic losses from heat stress by US livestock industries. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, E52–E77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, S.G.C.G.D.; Saraiva, E.P.; Neto, S.G.; Maia, M.I.L.; Lees, A.M.; Sejian, V.; Maia, A.S.C.; de Medeiros, G.R.; Fonsêca, V.D.F.C. Heat tolerance, thermal equilibrium and environmental management strategies for dairy cows in intertropical regions. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 988775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alonso, W.J.; Schuck-Paim, C. Welfare Footprint Framework: Methodological Foundations and Quantitative Assessment Guidelines; Center for Welfare Metrics: São Paulo, Brazil, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schuck-Paim, C.; Alonso, W.J.; Pereira, P.A.; Saraiva, J.L.; Cerqueira, M.; Chiang, C.; Sneddon, L.U. Quantifying the welfare impact of air asphyxia in rainbow trout slaughter for policy and practice. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 19850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuck-Paim, C.; Alonso, W.J.; Verkuijl, C.; Hegwood, M.; Hartcher, K. The Welfare Footprint Framework can help balance animal welfare with other food system priorities. Nat. Food 2025, 6, 737–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khire, I.; Ryba, R. Are slow-growing broiler chickens actually better for animal welfare? Br. Poult. Sci. 2025, 66, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W.J.; Schuck-Paim, C. Pain-Track: A time-series approach for the description and analysis of the burden of pain. BMC Res. Notes 2021, 14, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, W.J.; Schuck-Paim, C. (Eds.) Quantifying Pain in Laying Hens: A Blueprint for the Comparative Analysis of Welfare in Animals; Center for Welfare Metrics: São Paulo, Brazil, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, R.G.; Maia, A.S.C.; de Macedo Costa, L.L. Index of thermal stress for cows under high solar radiation in tropical environments. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2015, 59, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowan, T.; Wheeler, M.C.; Cobon, D.H.; Gaughan, J.B.; Marshall, A.G.; Sharples, W.; McCulloch, J.; Jarvis, C. Observed climatology and variability of cattle heat stress in Australia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 2024, 63, 645–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Moriasi, D.; Cibils, A.; Barker, P. Increasing frequency and spatial extent of cattle heat stress conditions in the Southern Plains of the USA. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morignat, E.; Gay, E.; Vinard, J.-L.; Calavas, D.; Hénaux, V. Quantifying the influence of ambient temperature on dairy and beef cattle mortality in France. Environ. Res. 2015, 140, 524–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernabucci, U.; Lacetera, N.; Baumgard, L.H.; Rhoads, R.P.; Ronchi, B.; Nardone, A. Metabolic and hormonal acclimation to heat stress in domesticated ruminants. Animal 2010, 4, 1167–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shephard, R.W.; Maloney, S.K. A review of thermal stress in cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 2023, 101, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, A.S.C.; Moura, G.A.B.; Fonsêca, V.F.C.; Gebremedhin, K.G.; Milan, H.M.; Neto, M.C.; Simão, B.R.; Campanelli, V.P.C.; Pacheco, R.D.L. Economically sustainable shade design for feedlot cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1110671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MEPS International. Latin America Steel Prices. Available online: https://mepsinternational.com/gb/en/products/latin-america-steel-prices (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Edwards-Callaway, L.N.; Cramer, M.C.; Cadaret, C.N.; Bigler, E.J.; Engle, T.E.; Wagner, J.J.; Clark, D.L. Impacts of shade on cattle well-being in the beef supply chain. J. Anim. Sci. 2021, 99, skaa375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, D.; Maloney, S.K.; Snelling, E.P.; Fonsêca, V.F.C.; Fuller, A. Measurement of microclimates in a warming world: Problems and solutions. J. Exp. Biol. 2024, 227, jeb246481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajjanar, B.; Aalam, M.T.; Khan, O.; Dhara, S.K.; Ghosh, J.; Gandham, R.K.; Gupta, P.K.; Chaudhuri, P.; Dutt, T.; Singh, G.; et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation profiles regulate distinct heat stress responses in zebu and crossbred cattle. Cell Stress Chaperones 2024, 29, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lees, A.M.; Sejian, V.; Wallage, A.L.; Steel, C.C.; Mader, T.L.; Lees, J.C.; Gaughan, J.B. The impact of heat load on cattle. Animals 2019, 9, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, R.J.; Baumgard, L.H.; Zimbelman, R.B.; Xiao, Y. Heat stress: Physiology of acclimation and adaptation. Anim. Front. 2019, 9, 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz, M. From molecular and cellular to integrative heat defense during exposure to chronic heat. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2002, 131, 475–483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown-Brandl, T.M. Understanding heat stress in beef cattle. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2018, 47, e20160414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.; Uddin, J.; Sullivan, M.; McNeill, D.M.; Phillips, C.J.C. Non-invasive physiological indicators of heat stress in cattle. Animals 2021, 11, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, D.T. Prolonged and Continuous Heat Stress in Cattle. Ph.D. Thesis, Murdoch University, Perth, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, M.D.; Rhoads, R.P.; Sanders, S.R.; Duff, G.C.; Baumgard, L.H. Metabolic adaptations to heat stress in growing cattle. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2010, 38, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, J.B.; Bonner, S.; Loxton, I.; Mader, T.L.; Lisle, A.; Lawrence, R. Effect of shade on body temperature and performance of feedlot steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2010, 88, 4056–4067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Shu, H.; Sun, F.; Yao, J.; Gu, X. Impact of heat stress on blood, production, and physiological indicators in heat-tolerant and heat-sensitive dairy cows. Animals 2023, 13, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Devaraj, C.; Rashamol, V.P.; Pragna, P.; Lees, A.M.; Sejian, V. The impact of heat stress on the immune system in dairy cattle: A review. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 126, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires, B.V.; Stafuzza, N.B.; Lima, S.B.G.P.N.P.; Negrão, J.A.; Paz, C.C.P. Differential expression of heat shock protein genes associated with heat stress in Nelore and Caracu beef cattle. Livest. Sci. 2019, 230, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-S.; Jo, Y.-H.; Nejad, J.G.; Lee, H.-G. Effects of heat shock protein 70 gene polymorphism on heat resistance in beef and dairy calves. Animals 2025, 15, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.-S.; Nejad, J.G.; Park, K.-K.; Lee, H.-G. Heat stress effects on physiological and blood parameters and behavior in early fattening beef steers. Animals 2023, 13, 1130. [Google Scholar]

- Slayi, M.; Jaja, I.F. Strategies for mitigating heat stress and their effects on behavior, physiological indicators, and growth performance in communally managed feedlot cattle. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1513368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idris, M. Behavioural Alterations in Heat-Stressed Cattle. Anim. Behav. Welf. Cases 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, C.C.; Peripolli, V.; Amador, S.A.; Brandão, E.G.; Esteves, G.I.F.; Sousa, C.M.Z.; França, M.F.M.S.; Gonçalves, F.G.; Barbosa, F.A.; Montalvão, T.C.; et al. Physiological and thermographic response to heat stress in zebu cattle. Livest. Sci. 2015, 182, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, W.C.; Silva, J.A.R.; Silva, É.B.R.; Barbosa, A.V.C.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Carvalho, K.C.; Santos, M.R.P.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Martorano, L.G.; Júnior, R.N.C.; et al. Characterization of thermal patterns using infrared thermography in cattle reared in three systems in the Eastern Amazon. Animals 2023, 13, 2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, S.R. Behavioural, physiological, neuro-endocrine and molecular responses of cattle against heat stress: An updated review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2021, 53, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.M.D.; Souza-Junior, J.B.F.; Dantas, M.R.T.; de Macedo Costa, L.L. An updated review on cattle thermoregulation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 30471–30485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhardt, E.P.; Kim, J. Prolonged heat stress impacts molecular responses of skeletal muscle and growth performance in finishing beef steers. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, 223–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, J.B.; Mader, T.L. Body temperature and respiratory dynamics in unshaded beef cattle. Int. J. Biometeorol. 2014, 58, 1443–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, M.; Sullivan, M.; Gaughan, J.B.; Phillips, C.J.C. Behavioural responses of beef cattle to hot conditions. Animals 2024, 14, 2444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashamol, V.P.; Sejian, V.; Bagath, M.; Krishnan, G.; Archana, P.R.; Bhatta, R. Physiological adaptability of livestock to heat stress. J. Anim. Behav. Biometeorol. 2018, 6, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.E.; Eletu, T.A.; Akosile, O.A.; Fasasi, L.O.; Adeniji, O.E.; Ojedokun, M.Z.; Oni, A.I. Behavioural adaptations of livestock to environmental stressors. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2025, 53, 2583108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, V.S.; da Silva Menezes, B.; Lopes, M.G.; Malaguez, E.G.; Lopes, F.; Pereira, F.M.; Brauner, C.C.; Moriel, P.; Corrêa, M.N.; Schmitt, E.; et al. Rumen-protected methionine modulates body temperature in grazing heat-stressed Bos indicus cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2024, 95, e13980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beatty, D.T.; Barnes, A.; Taylor, E.; Pethick, D.; McCarthy, M.; Maloney, S.K. Physiological responses of Bos taurus and Bos indicus cattle to prolonged heat and humidity. J. Anim. Sci. 2006, 84, 972–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, W.C.; da Silva, J.A.R.; Martorano, L.G.; da Silva, É.B.R.; de Carvalho, K.C.; Sousa, C.E.L.; Neves, K.A.L.; Camargo, R.N.C.; Belo, T.S.; Santos, A.G.S. Thermal comfort of Nellore cattle in silvopastoral and traditional systems in the Eastern Amazon. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 236. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, D.W.; Barnes, A.L.; Collins, T.; Pannier, L.; Aleri, J.; Maloney, S.K.; Anderson, F. Welfare and performance benefits of shade provision during summer for feedlot cattle. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Laer, E.; Moons, C.P.H.; Ampe, B.; Sonck, B.; Vandaele, L.; De Campeneere, S.; Tuyttens, F.A.M. Effect of summer conditions and shade on behavioural indicators of thermal discomfort in cattle on pasture. Animal 2015, 9, 1536–1546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turcios, S.E.M.; Rotz, C.A.; McGlone, J.; Rivera, C.R.; Mitloehner, F.M. Effects of heat stress mitigation strategies on feedlot cattle performance and economic outcomes. Animal 2024, 18, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero, M.J.; Palhares, J.C.P.; Novelli, T.I.; Martello, L.S.; Pérez-Márquez, S.; Cooke, A.S. Shade provision and drinking behaviour of Nellore cattle in tropical feedlots. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0331238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, L.A.; Canozzi, M.E.A.; Rodhermel, J.C.B.; Schwegler, E.; La Manna, A.; Clariget, J.; Bianchi, I.; Moreira, F.; Olsson, D.C.; Peripolli, V. Strategies to alleviate heat stress in feedlot cattle: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Therm. Biol. 2024, 119, 103798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashiru, H.A.; Oseni, S.O. Simplified climate change adaptation strategies for livestock development in low- and middle-income countries. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oke, O.E.; Uyanga, V.A.; Oretomiloye, F.; Abioja, M.O. Climate-smart livestock production: Strategies for enhanced sustainability and resilience. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1638289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei-Ahvanooei, M.R.; Lamanna, M.; Colleluori, R.; Formigoni, A.; Norouzian, M.A.; Assadi-Alamouti, A.; Cavallini, D. Effects of microminerals on performance and metabolic adaptation in heat-stressed dairy cows. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2025, 213, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.R. Risk factors for bovine respiratory disease in beef cattle. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2020, 21, 149–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Risk Category | ATL (°C) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Low | <100 | Days exceeding threshold are rare or show minimal excess (e.g., ATL of 50 °C could result from 10 days at CCI 35 °C–5 °C excess daily or 50 days at 31 °C–1 °C excess daily). Animals experience minimal thermoregulatory challenges above stress thresholds. |

| Moderate | 100–500 | More frequent exposure to challenging thermal conditions. Animals regularly experience “moderate stress” days (30–35 °C) or fewer days at higher stress levels. Periods requiring active thermoregulation occur with some regularity. |

| High | 500–1200 | Considerable and frequent exposure to significant heat stress. Animals likely experience multiple days of “moderate to severe stress” (often >35 °C). For example, an ATL of 1000 °C could emerge from 100 days at CCI of 40 °C. |

| Very High | 1200–2000 | Substantial thermal load with frequent days of “severe stress” CCI level and some probable “extreme stress” days (>40 °C). |

| Extreme | >2000 | Highest criticality level. Animals face prolonged “severe stress” periods and frequent “extreme stress” CCI or “extreme danger” CCI days, indicating chronic exposure to extremely adverse thermal conditions. |

| CCI Stress Category | Thermal Risk Based on the Average Annual Thermal Load | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate Risk | High Risk | Very High Risk | Extreme Risk | |

| Moderate (30–35 °C) | (1) M-M | (2) M-H | (3) M-VH | (4) M-E |

| Strong (35–40 °C) | (5) S-M | (6) S-H | (7) S-VH | (8) S-E |

| Extreme (40–45 °C) | — | (9) E-H | (10) E-VH | (11) E-E |

| Extreme Danger (>45 °C) | — | — | (12) ED-VH | (13) ED-E |

| Scenario | Duration | Justification |

|---|---|---|

| (1) M-M | 5–7 | Locations predominantly in subtropical regions with moderate humidity and higher diurnal variation. CCI is expected to cross the 30 °C threshold from approximately 10–11 am to 4–5 pm when solar radiation peaks. Nights drop below threshold allowing recovery. |

| (2) M-H | 7–9 | Transitional tropical zones (Goiás, southern Cerrado) with increasing humidity. Higher humidity extends morning and evening discomfort periods. CCI expected to exceed 30 °C by ~9–10 am until 5–6 pm. |

| (3) M-VH | 9–11 | Northern Mato Grosso, Amazon edges. High humidity (>70%) means even 25–27 °C air temperature at 8 am produces CCI > 30 °C. Discomfort likely to persist until 7 pm despite moderate air temperatures. |

| (4) M-E | 10–12 | Scenario represents coolest days in extreme tropical zones. Even on moderate days, humidity > 75% and nighttime temperatures of about 24–25 °C mean CCI rarely drops below 30 °C. Nearly all daylight hours thermal stress. |

| (5) S-M | 5–7 | Regions with large diurnal variation allows brief but intense peaks. CCI reaches 35–40 °C for the afternoon period (12–5 pm) but substantial cooling at night. |

| (6) S-H | 8–10 | Humidity reduces nighttime cooling. CCI exceeds 35 °C from 10 am−6 pm with slower morning warming and evening cooling due to moisture. |

| (7) S-VH | 10–12 | High humidity throughout the day. Even at 8–9 am, temp of 28 °C + humidity + early sun produces CCI > 35 °C. Remains high past sunset. |

| (8) S-E | 11–13 | Common pattern in Rondônia. Minimal diurnal variation (nighttime CCI ~31–32 °C) means achieving a daily average of 35–40 °C requires nearly continuous elevation. Relief only in pre-dawn hours. |

| (9) E-H | 7–9 | Rare combination. When extreme days occur in high chronic areas, usually from dry heat waves allowing some nighttime recovery despite intense day stress. |

| (10) E-VH | 9–11 | Peak days in very hot regions. To average 40–45 °C requires sustained extreme conditions throughout daylight. |

| (11) E-E | 10–12 | Nighttime CCI remains >35 °C, daytime exceeds 45 °C. Daily averaging implies 10+ h in extreme range. |

| (12) ED-VH | 8–10 | Exceptional heat events. Despite catastrophic peaks, some diurnal variation still exists in VH regions, concentrating most severe stress in an 8 to 10 h window. |

| (13) ED-E | 10–12 | Extreme events in extreme regions. A daily average > 45 °C requires most of the day above this threshold. Nighttime may only drop slightly. |

| Scenario | I | II | III | Justification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) M-M | 1–2 | 2–3 | 1–2 | Initial: Respiratory rate gradually increases from baseline to first-stage panting, core temperature rises. This mobilization was estimated at 1–2 h. Overload: sustained panting with increased water consumption and reduced feed intake before metabolic shifts occur. Recovery: as evening cooling begins, respiratory rate gradually decreases toward baseline |

| (2) M-H | 1.5–2.5 | 3–4 | 2–2.5 | Initial: Similar physiological progression but chronic exposure may blunt HPA response, delaying vasodilation, sweating. Overload: Reduced sweating may require maintaining panting longer to achieve similar cooling. Recovery: Higher cortisol and incomplete cooling extend recovery. |

| (3) M-VH | 2–2.5 | 4–5 | 3–3.5 | Initial: receptor downregulation expected to delay initial panting response and vasodilation. Overload: With sweat glands potentially lower efficiency, animals may need to sustain compensatory panting longer. Recovery: With nighttime CCI remaining high, only partial RR reduction is expected. |

| (4) M-E | 2–3 | 5–6 | 3–3.5 | Initial: Severe chronic exhaustion may maximally delay autonomic responses, longer to first-stage panting. Overload: Extreme depletion force prolonged low-efficiency compensation. Recovery: No return to baseline. |

| (5) S-M | 1–1.5 | 2.5–3.5 | 1.5–2 | Initial: Higher thermal gradient (CCI 35–40 °C) expected to trigger panting within 1–1.5 h. Overload: Second-stage panting with intact reserves. Recovery: Large evening temperature drop allows RR to normalize. |

| (6) S-H | 1.5–2 | 4–5 | 2.5–3 | Initial: Emergency panting response potentially delayed by chronic fatigue. Overload: Depleted reserves may require panting longer before exhaustion. Recovery: Smaller diurnal cooling prolongs high RR. |

| (7) S-VH | 2–2.5 | 5–6 | 3–3.5 | Initial: Despite strong stress, severe chronic fatigue may delay maximum panting. Overload: Near-maximal respiratory effort with compromised efficiency. Recovery: Minimal temperature relief means RR remains high. |

| (8) S-E | 2.5–3 | 6–7 | 2.5–3 | Initial: Extreme exhaustion may severely delay even emergency response. Overload: Prolonged struggle at minimal efficiency. Recovery: No respiratory normalization, only reduced panting |

| (9) E-H | 0.5–1 | 3–4 | 3.5–4 | Initial: Extreme heat may trigger crisis panting. Overload: Physiological ceiling reached more quickly but respiratory alkalosis may limit duration. Recovery: Cellular damage from extreme panting likely. |

| (10) E-VH | 0.5–1 | 4–5 | 4.5–5 | Initial: Immediate crisis response with maximum panting. Overload: ceiling-level panting despite alkalosis risk. Recovery: Severe physiological damage may prolong dysfunction. |

| (11) E-E | 0.5–1 | 4.5–5.5 | 5–5.5 | Initial: Despite exhaustion, life-threat likely triggers maximum panting quickly. Overload: Sustained at respiratory ceiling until exhaustion. Recovery: thermoregulatory failure maintains dysfunction. |

| (12) ED-VH | 0.25–0.5 | 3–4 | 4.75–5.5 | Initial: Extreme heat likely triggers immediate maximum response. Overload: Acute respiratory failure may limit active panting. Recovery: If survival occurs, critical dysfunction is expected |

| (13) ED-E | 0.25–0.5 | 3.5–4.5 | 6.25–7 | Initial: Immediate but potentially impaired crisis panting. Overload: Slightly prolonged by inability to mount full response. Recovery: Maximum thermoregulatory dysfunction. |

| Summary of Evidence | Intensity Hypothesis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | A | H | D | E | ||

| I | Respiratory rate increases from baseline to first-stage panting | − | + | + | − | R |

| Animals reduce but maintain grazing, seeking shade intermittently (CI) | − | + | + | R | R | |

| Core temperature rises above normal range (38.0–39.3 °C) (CI) | ? | + | ? | ? | − | |

| Cortisol levels show initial elevation above baseline | − | + | + | ? | ? | |

| Animals maintain social interactions but reduce exploratory behavior (CI) | − | + | + | R | R | |

| From evolutionary perspective, moderate thermal challenge requires aversive signaling to motivate behavioral adjustments | − | + | + | + | − | |

| II | Respiratory rate includes open-mouth panting | − | ? | + | + | − |

| Behavioral depression, cessation of voluntary activities. prolonged standing | R | − | + | + | − | |

| Core temperature rises even more above normal, approaching 41 °C | − | − | ? | ? | − | |

| Sustained cortisol elevation likely indicating severe physiological stress | − | + | + | ? | − | |

| Drooling and signs of respiratory alkalosis from excessive panting | R | − | + | ? | − | |

| Feed intake suppressed, water consumption typically increases | R | − | + | + | − | |

| Evolutionary perspective: prolonged, although moderate, thermal challenge requires aversive signaling | R | ? | + | + | − | |

| III | Respiratory rate gradually decreases but often still high (CI) | − | + | ? | ? | − |

| Gradual resumption of grazing and social behaviors | − | + | ? | R | R | |

| Core temperature slowly returns toward baseline | − | ? | ? | − | − | |

| Cortisol levels decline but may remain above baseline | ? | + | ? | ? | − | |

| Residual metabolic disruption from lactate accumulation during overload (CI) | − | + | ? | ? | − | |

| (A) Pain-Track | I. Initial Stress | II. Overload | III. Recovery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excruciating | |||||||

| Disabling | 10% | ||||||

| Hurtful | 30% | 80% | 10% | ||||

| Annoying | 60% | 10% | 60% | ||||

| None | 10% | 30% | |||||

| Duration: | 1–2 h | 2–3 h | 1–2 h | ||||

| (B) Cumulative Pain | I. Initial Stress | II. Overload | III. Recovery | Cumulative Pain | |||

| Excruciating | |||||||

| Disabling | 0.2–0.3 h | 0.2–0.3 h | |||||

| Hurtful | 0.3–0.6 h | 1.6–2.4 h | 0.1–0.2 h | 2–3.2 h | |||

| Annoying | 0.6–1.2 h | 0.2–0.3 h | 0.6–1.2 h | 1.4–2.7 h | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Schuck-Paim, C.; Alonso, W.J.; Freitas, A.d.P.; de Oliveira, C.P.; Fonseca, V.d.F.C.; Borges, T.D. The Welfare Impact of Heat Stress in South American Beef Cattle and the Cost-Effectiveness of Shade Provision. Animals 2026, 16, 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020231

Schuck-Paim C, Alonso WJ, Freitas AdP, de Oliveira CP, Fonseca VdFC, Borges TD. The Welfare Impact of Heat Stress in South American Beef Cattle and the Cost-Effectiveness of Shade Provision. Animals. 2026; 16(2):231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020231

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchuck-Paim, Cynthia, Wladimir Jimenez Alonso, Anielly de Paula Freitas, Camila Pereira de Oliveira, Vinicius de França Carvalho Fonseca, and Tâmara Duarte Borges. 2026. "The Welfare Impact of Heat Stress in South American Beef Cattle and the Cost-Effectiveness of Shade Provision" Animals 16, no. 2: 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020231

APA StyleSchuck-Paim, C., Alonso, W. J., Freitas, A. d. P., de Oliveira, C. P., Fonseca, V. d. F. C., & Borges, T. D. (2026). The Welfare Impact of Heat Stress in South American Beef Cattle and the Cost-Effectiveness of Shade Provision. Animals, 16(2), 231. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020231