Genomic Differentiation and Diversity in Persian Gulf Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) Revealed by the First Whole-Genome Sequencing Study

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection, DNA Extraction, and Sequencing

2.2. Alignment, Genotyping and Variant Calling

2.3. Genetic Structure and Phylogenetic Inference

2.4. Genetic Diversity and Inbreeding Parameters

3. Results

3.1. Mapping Outputs

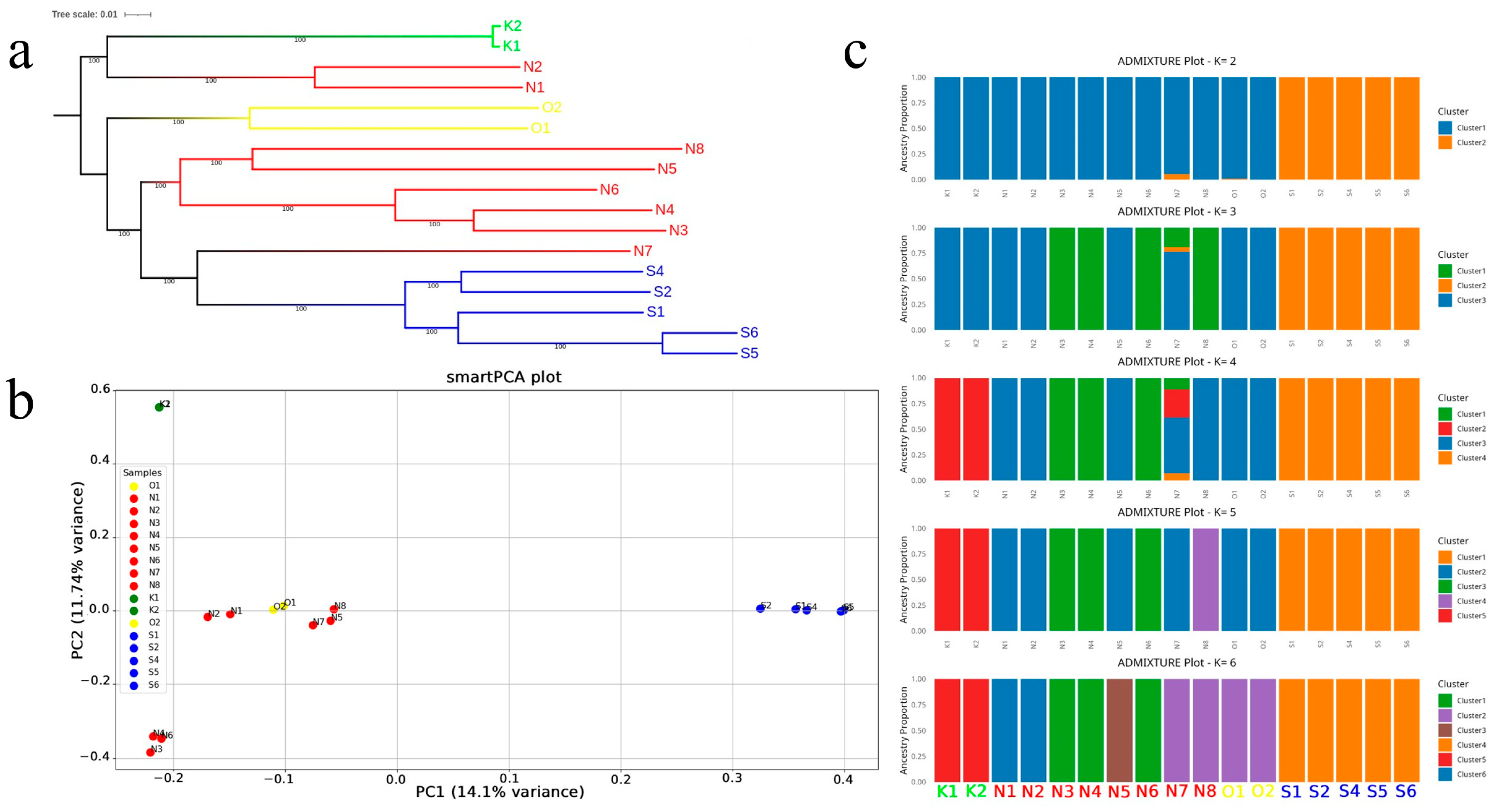

3.2. Population Structure Analysis

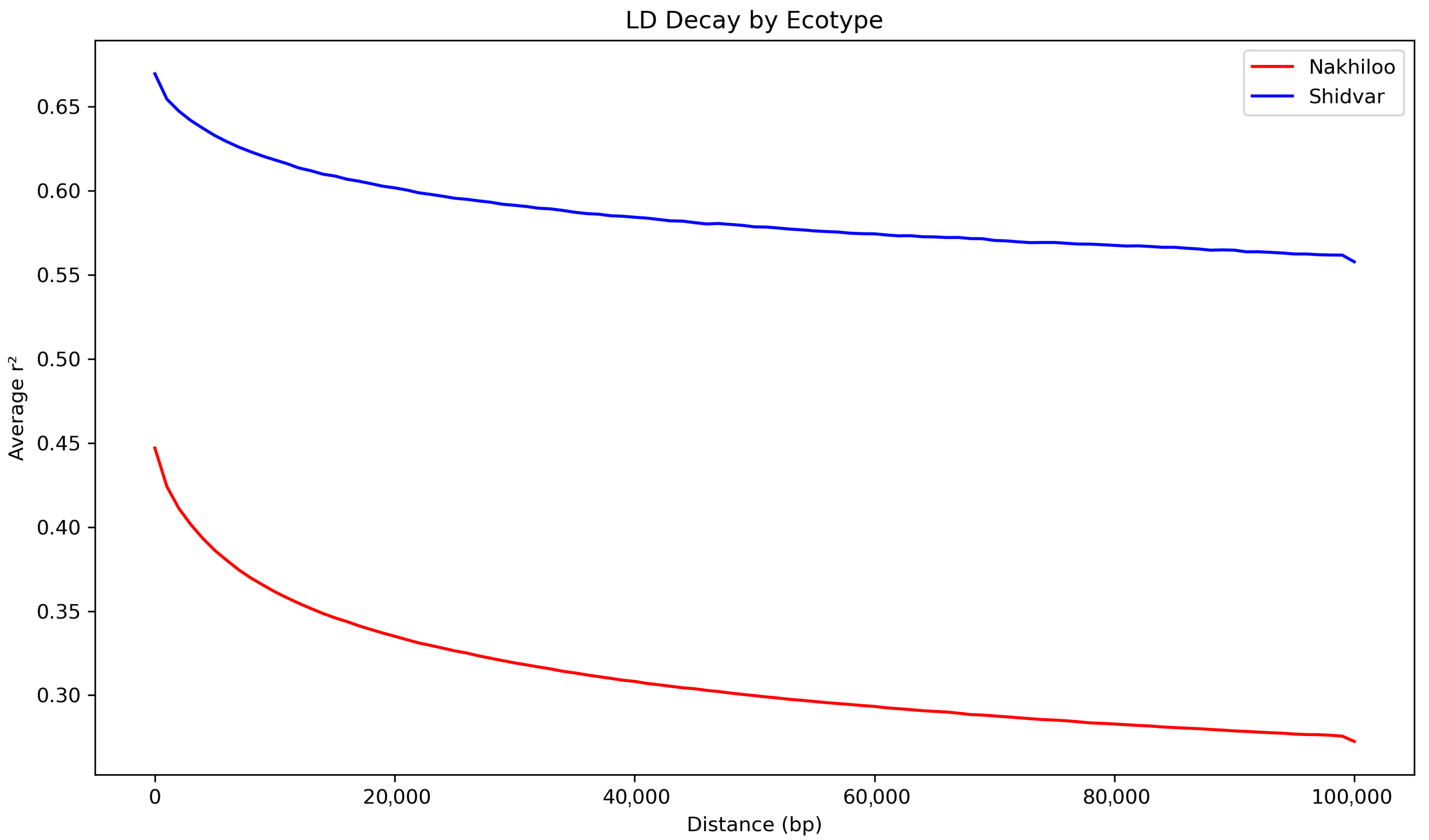

3.3. Genomic Diversity and Inbreeding

4. Discussion

4.1. Population-Level Genetic Structure

4.2. Genetic Diversity and Inbreeding

4.3. Conservation Implications and Recommendations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kämpf, J.; Sadrinasab, M. The circulation of the Persian Gulf: A numerical study. Ocean Sci. 2006, 2, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori Koupaei, A.; Mostafavi, P.G.; Mehrabadi, J.; Fatemi, S. Molecular diversity of coral reef-associated zoanthids off Qeshm Island, northern Persian Gulf. Int. Aquat. Res. 2014, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spalding, M.D.; Fox, H.E.; Allen, G.R.; Davidson, N.; Ferdaña, Z.A.; Finlayson, M.; Halpern, B.S.; Jorge, M.A.; Lombana, A.; Lourie, S.A.; et al. Marine Ecoregions of the World: A Bioregionalization of Coastal and Shelf Areas. BioScience 2007, 57, 573–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, B.C.C.; Voolstra, C.R.; Arif, C.; D’Angelo, C.; Burt, J.A.; Eyal, G.; Loya, Y.; Wiedenmann, J. Ancestral genetic diversity associated with the rapid spread of stress-tolerant coral symbionts in response to Holocene climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 4416–4421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.G.; Vaughan, G.O.; Ketchum, R.N.; McParland, D.; Burt, J.A. Symbiont community stability through severe coral bleaching in a thermally extreme lagoon. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howells, E.J.; Bauman, A.G.; Vaughan, G.O.; Hume, B.C.C.; Voolstra, C.R.; Burt, J.A. Corals in the hottest reefs in the world exhibit symbiont fidelity not flexibility. Mol. Ecol. 2020, 29, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salimi, M.; Ghavam-Mostafavi, P.; Fatemi, S.M.R.; Aeby, G.S. Health status of corals surrounding Kish Island, Persian Gulf. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2017, 124, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riegl, B.M.; Purkis, S.J.; Al-Cibahy, A.S.; Abdel-Moati, M.A.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O. Present limits to heat-adaptability in corals and population-level responses to climate extremes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwmeester, J.; Riera, R.; Range, P.; Ben-Hamadou, R.; Samimi-Namin, K.; Burt, J.A. Coral and reef fish communities in the thermally extreme Persian/Arabian Gulf: Insights into potential climate change effects. In Perspectives on the Marine Animal Forests of the World; Rossi, S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobaraki, A.; Rastegar-Pouyani, E.; Kami, H.; Khorasani, N. Population study of foraging green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in the Northern Persian Gulf and Oman Sea, Iran. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2020, 39, 101433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, B.W.; Karl, S.A. Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 4886–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, B.P.; DiMatteo, A.D.; Bolten, A.B.; Chaloupka, M.Y.; Hutchinson, B.J.; Abreu-Grobois, F.A.; Mortimer, J.A.; Seminoff, J.A.; Amorocho, D.; Bjorndal, K.A.; et al. Global conservation priorities for marine turtles. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e24510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, L.A.; Broderick, A.C.; Godfrey, M.H.; Godley, B.J. Investigating the potential impacts of climate change on a marine turtle population. Glob. Change Biol. 2007, 13, 923–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witt, M.J.; Hawkes, L.A.; Godfrey, M.H.; Godley, B.J.; Broderick, A.C. Predicting the impacts of climate change on a globally distributed species: The case of the loggerhead turtle. J. Exp. Biol. 2010, 213, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloë, J.O.; Schofield, G.; Hays, G.C. Climate warming and sea turtle sex ratios across the globe. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IUCN. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, Version 2024-1. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org (accessed on 18 July 2024).

- Nasiri, Z.; Gholamalifard, M.; Ghasempouri, S.M. Determining nest site selection by hawksbill sea turtles in the Persian Gulf using unmanned aerial vehicles. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2022, 21, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaghian, H.; Shams-Esfandabad, B.; Askari Hesni, M.; Vafaei, R.; Toranjzar, H.; Miller, J. Distribution patterns of epibiotic barnacles on the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting in Iran. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2019, 27, 100527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, Y.M.; Bjorndal, K.A. Selective feeding in the hawksbill turtle, an important predator in coral reef ecosystems. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2002, 245, 249–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Brandis, R.; Mortimer, J.; Reilly, B.; van Soest, R.; Branch, G. Diet composition of hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Republic of Seychelles. Herpetol. Conserv. Biol. 2014, 13, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Frankham, R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 126, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baas, P.; van der Valk, T.; Vigilant, L.; Ngobobo, U.; Binyinyi, E.; Nishuli, R.; Caillaud, D.; Guschanski, K. Population-level assessment of genetic diversity and habitat fragmentation in critically endangered Grauer’s gorillas. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2018, 165, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ji, X.Y.; Dai, G.; Gu, Z.; Ming, C.; Yang, Z.; Ryder, O.A.; Li, W.H.; Fu, Y.X.; Zhang, Y.P. Large numbers of vertebrates began rapid population decline in the late 19th century. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 14079–14084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yao, M. Low genetic diversity in a critically endangered primate: Shallow evolutionary history or recent population bottleneck? BMC Evol. Biol. 2019, 19, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, D.J. Genetic diversity of small populations: Not always “doom and gloom”? Mol. Ecol. 2017, 26, 6499–6501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casillas, S.; Barbadilla, A. Molecular population genetics. Genetics 2017, 205, 1003–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, B.; Charlesworth, D. Population genetics from 1966 to 2016. Heredity 2017, 118, 2–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grueber, C.E.; Wallis, G.P.; Jamieson, I.G. Heterozygosity-fitness correlations and their relevance to studies on inbreeding depression in threatened species. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 3978–3984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primmer, C.R. From conservation genetics to conservation genomics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2009, 1162, 357–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wakeley, J. Recent trends in population genetics: More data! More math! Simple models? J. Hered. 2004, 95, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, H.; Hu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Nie, Y.; Yan, L.; Wei, F. Conservation genetics and genomics of threatened vertebrates in China. J. Genet. Genom. 2018, 45, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouborg, N.J. Integrating population genetics and conservation biology in the era of genomics. Biol. Lett. 2010, 6, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoridis, S.; Fordham, D.A.; Brown, S.C.; Li, S.; Rahbek, C.; Nogués-Bravo, D. Evolutionary history and past climate change shape the distribution of genetic diversity in terrestrial mammals. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, A.V.; Hansson, B.; Patramanis, I.; Morales, H.E.; van Oosterhout, C. The impact of habitat loss and population fragmentation on genomic erosion. Conserv. Genet. 2024, 25, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza, J.A.; Sánchez-Fernández, B.; Fandos, P.; Soriguer, R. Intensive management and natural genetic variation in red deer (Cervus elaphus). J. Hered. 2017, 108, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, A.B.A.; Wolf, J.B.W.; Alves, P.C.; Bergström, L.; Bruford, M.W.; Brännström, I.; Colling, G.; Dalén, L.; De Meester, L.; Ekblom, R.; et al. Genomics and the challenging translation into conservation practice. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2015, 30, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, C.C.; Putnam, A.S.; Hoeck, P.E.A.; Ryder, O.A. Conservation genomics of threatened animal species. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2013, 1, 261–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; FitzSimmons, N.N.; Dutton, P.H. Molecular genetics of sea turtles. In The Biology of Sea Turtles; Wyneken, J., Lohmann, K.J., Musick, J.A., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2013; Volume III, pp. 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, B.P.; Carrasco-Valenzuela, T.; Ramos, E.K.S.; Pawar, H.; Souza, L.; Alexander, A.; Banerjee, S.M.; Masterson, P.; Kuhlwilm, M.; Pippel, M.; et al. Divergent sensory and immune gene evolution in sea turtles with contrasting demographic and life histories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2201076120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hesni, M.A.; Rezaie-Atagholipour, M.; Zangiabadi, S.; Tollab, M.A.; Moazeni, M.; Jafari, H.; Talebi Matin, M.; Ghorbanzadeh Zafarani, G.; Shojaei, M.; Motlaghnejad, A. Monitoring hawksbill turtle nesting sites in some protected areas from the Persian Gulf. Acta Oceanol. Sin. 2019, 38, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarei, M.; Moradi, A.; Rezai, M.; Ibrahim, Z. Investigating the effect of recreation on the sustainability of tourism in the raised shores of the international lagoon of Shidvar Island. J. Geogr. Plan. 2024, 28, 119–138. [Google Scholar]

- Debler, J.W.J.; Jones, A.W.; Nagar, R.; Sharp, A.; Schwessinger, B. High-Molecular Weight DNA Extraction and Small Fragment Removal of Ascochyta lentis. Protocols.io. 2020. Available online: https://www.protocols.io/view/high-molecular-weight-dna-extraction-and-small-fra-3byl478jjlo5/v1 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data; Babraham Bioinformatics: Cambridge, UK, 2010; Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Schubert, M.; Lindgreen, S.; Orlando, L. AdapterRemoval v2: Rapid adapter trimming, identification, and read merging. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhuo, Z.; Huang, J.; Fu, Z.; Song, J.; Liu, M.; Dong, Z.; Wang, Z. The first high-quality chromosome-level genome of Eretmochelys imbricata using HiFi and Hi-C data. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N.; Marth, G.; Abecasis, G.; Durbin, R.; 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broad Institute. Picard Tools. Available online: https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- McKenna, A.; Hanna, M.; Banks, E.; Sivachenko, A.; Cibulskis, K.; Kernytsky, A.; Garimella, K.; Altshuler, D.; Gabriel, S.; Daly, M.; et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: A MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010, 20, 1297–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darriba, D.; Posada, D.; Kozlov, A.M.; Stamatakis, A.; Morel, B.; Flouri, T. ModelTest-NG: A new and scalable tool for the selection of DNA and protein evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 291–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, B.Q.; Schmidt, H.A.; Chernomor, O.; Schrempf, D.; Woodhams, M.D.; von Haeseler, A.; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020, 37, 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v6: An online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.; Neale, B.; Todd-Brown, K.; Thomas, L.; Ferreira, M.A.R.; Bender, D.; Maller, J.; Sklar, P.; de Bakker, P.I.W.; Daly, M.J.; et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007, 81, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, N.; Price, A.L.; Reich, D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006, 2, e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.H.; Novembre, J.; Lange, K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danecek, P.; Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.; Albers, C.A.; Banks, E.; DePristo, M.A.; Handsaker, R.E.; Lunter, G.; Marth, G.T.; Sherry, S.T.; et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 2156–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speciation Genomics. LD Decay Analysis. Speciation Genomics How-To Guide 2023. Available online: https://speciationgenomics.github.io/ld_decay (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Karimi, K.; Farid, A.H.; Sargolzaei, M.; Myles, S.; Miar, Y. Linkage disequilibrium, effective population size and genomic inbreeding rates in American mink using genotyping-by-sequencing data. Front. Genet. 2020, 11, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabib, M.; Zolgharnein, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Salari-Aliabadi, M.A.; Qasemi, A.; Roshani, S.; Rajabi-Maham, H.; Frootan, F. mtDNA variation of the critically endangered hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting on Iranian islands of the Persian Gulf. Genet. Mol. Res. 2011, 10, 1499–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolgharnein, H.; Salari-Aliabadi, M.A.; Forougmand, A.M.; Roshani, S. Genetic population structure of hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) using microsatellite analysis. Iran. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 9, 56–62. Available online: https://www.ijbiotech.com/article_7147.html (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Nasiri, Z.; Gholamalifard, M.; Mohammadi, M.; Jebeli, S.; Dakhteh, S.; Ghavasi, M.; Tollab, A.; Ghasempouri, S.M. Population genetics of the hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata; Linnaeus, 1766) in the Persian Gulf: Structure and historical demography. Aquat. Sci. 2025, 87, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabib, M.; Frootan, F.; Askari Hesni, M. Genetic diversity and phylogeography of hawksbill turtle in the Persian Gulf. J. Biodivers. Environ. Sci. 2014, 4, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Sani, L.M.I.; Jamaludin; Hadiko, G.; Herma, E.; Inoguchi, E.; Jensen, M.P.; Madden, C.A.; Nishizawa, H.; Maryani, L.; Farajallah, A.; et al. Unraveling fine-scale genetic structure in endangered hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in Indonesia: Implications for management strategies. Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1358695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vélez-Zuazo, X.; Ramos, W.D.; Van Dam, R.; Diez, C.E.; Miller, M.W.; McMillan, W.O. Dispersal, recruitment and migratory behaviour in a hawksbill sea turtle aggregation. Mol. Ecol. 2008, 17, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blumenthal, J.M.; Abreu-Grobois, F.A.; Austin, T.J.; Broderick, A.C.; Bruford, M.W.; Coyne, M.S.; Ebanks-Petrie, G.; Formia, A.; Meylan, P.A.; Meylan, A.B.; et al. Turtle groups or turtle soup: Dispersal patterns of hawksbill turtles in the Caribbean. Mol. Ecol. 2009, 18, 4841–4853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, M.C.; Reisser, J.; Marins, L.F.; Marcovaldi, M.A.; Soares, L.S.; Monteiro, D.S.; Wijeratne, S.; Pattiaratchi, C.; Secchi, E.R. Hawksbill × loggerhead sea turtle hybrids at Bahia, Brazil: Where do their offspring go? PeerJ 2014, 2, e255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lohmann, K.J.; Lohmann, C.M.F. There and back again: Natal homing by magnetic navigation in sea turtles and salmon. J. Exp. Biol. 2019, 222, jeb184077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H.D.; Xue, P.; Eltahir, E.A.B. Multiple salinity equilibria and resilience of Persian/Arabian Gulf basin salinity to brine discharge. Front. Mar. Sci. 2020, 7, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayani, N. Ecology and environmental challenges of the Persian Gulf. Iran. Stud. 2016, 49, 1047–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilcher, N.J.; Antonopoulou, M.; Perry, L.; Abdel-Moati, M.A.; Al Abdessalaam, T.Z.; Albeldawi, M.; Al Ansi, M.; Al-Mohannadi, S.F.; Al Zahlawi, N.; Baldwin, R.; et al. Identification of important sea turtle areas (ITAs) for hawksbill turtles in the Arabian region. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 460, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simões, T.N.; Maranhão dos Santos, E.; Souza Santos, A.; Amato Gaiotto, F.; Costa, M.A.; Cardoso de Menezes Assis, E.T.; Chimendes da Silva Neves, V.; Mendes de Santana Magalhães, W.; Mascarenhas, R.; Gomes Bonfim, W.A.; et al. Low diversity and strong genetic structure between feeding and nesting areas in Brazil for the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2021, 9, 704838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiong, R.; Dacanay, J.; Uchida, A.; Desai, A.; Kalsi, N.; Tong, C.; Kim, H.L. Population genomic analysis reveals high inbreeding in a hawksbill turtle population nesting in Singapore. bioRxiv 2023. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, A.B.A.; Kardos, M. Runs of homozygosity and inferences in wild populations. Mol. Ecol. 2025, 34, e17641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosse, M.; Megens, H.J.; Madsen, O.; Paudel, Y.; Frantz, L.A.F.; Schook, L.B.; Groenen, M.A.M. Regions of homozygosity in the porcine genome: Consequence of demography and the recombination landscape. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8, e1003100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, M.; Wang, J.; Liu, L.; Su, S.; Zhao, F.; Chen, H.; et al. Genome-wide detection of genetic structure and runs of homozygosity analysis in Anhui indigenous and Western commercial pig breeds using PorcineSNP80k data. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Prado-Martinez, J.; Sudmant, P.H.; Narasimhan, V.; Ayub, Q.; Szpak, M.; Frandsen, P.; Chen, Y.; Yngvadottir, B.; Cooper, D.N.; et al. Mountain gorilla genomes reveal the impact of long-term population decline and inbreeding. Science 2015, 348, 242–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arantes, L.S.; Vilaça, S.T.; Mazzoni, C.J.; Santos, F.R. New genetic insights about hybridization and population structure of hawksbill and loggerhead turtles from Brazil. J. Hered. 2020, 111, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Farahvashi, M.; Mohammadabadi, M.; Askari-Hesni, M.; Amiri Ghanatsaman, Z.; Asadollahpour Nanaei, H. Genomic Differentiation and Diversity in Persian Gulf Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) Revealed by the First Whole-Genome Sequencing Study. Animals 2026, 16, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020169

Farahvashi M, Mohammadabadi M, Askari-Hesni M, Amiri Ghanatsaman Z, Asadollahpour Nanaei H. Genomic Differentiation and Diversity in Persian Gulf Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) Revealed by the First Whole-Genome Sequencing Study. Animals. 2026; 16(2):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020169

Chicago/Turabian StyleFarahvashi, Mohammadali, Mohammadreza Mohammadabadi, Majid Askari-Hesni, Zeinab Amiri Ghanatsaman, and Hojjat Asadollahpour Nanaei. 2026. "Genomic Differentiation and Diversity in Persian Gulf Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) Revealed by the First Whole-Genome Sequencing Study" Animals 16, no. 2: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020169

APA StyleFarahvashi, M., Mohammadabadi, M., Askari-Hesni, M., Amiri Ghanatsaman, Z., & Asadollahpour Nanaei, H. (2026). Genomic Differentiation and Diversity in Persian Gulf Hawksbill Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) Revealed by the First Whole-Genome Sequencing Study. Animals, 16(2), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020169