Functional Role and Diagnostic Potential of Biomarkers in the Early Detection of Mastitis in Dairy Cows

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Mastitis Classification

3. Current Diagnostic Methods for Bovine Mastitis

4. Characteristics of a Valid Biomarker

5. Structural and Functional Classes of Mastitis Biomarkers

5.1. Protein Biomarkers for Mastitis

5.1.1. Lactoferrin

5.1.2. β-Defensin 4

5.1.3. Vitronectin

5.1.4. Paraoxonase 1

5.1.5. N-Acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase

5.1.6. Cathelicidins

5.1.7. β-Lactoglobulin

5.1.8. General Considerations on Protein Biomarkers for the Diagnosis of Mastitis

5.2. Glucidic Biomarkers for Mastitis

Lactose

5.3. Molecular Biomarkers for Mastitis

5.3.1. Mitochondrial DNA

5.3.2. MicroRNAs

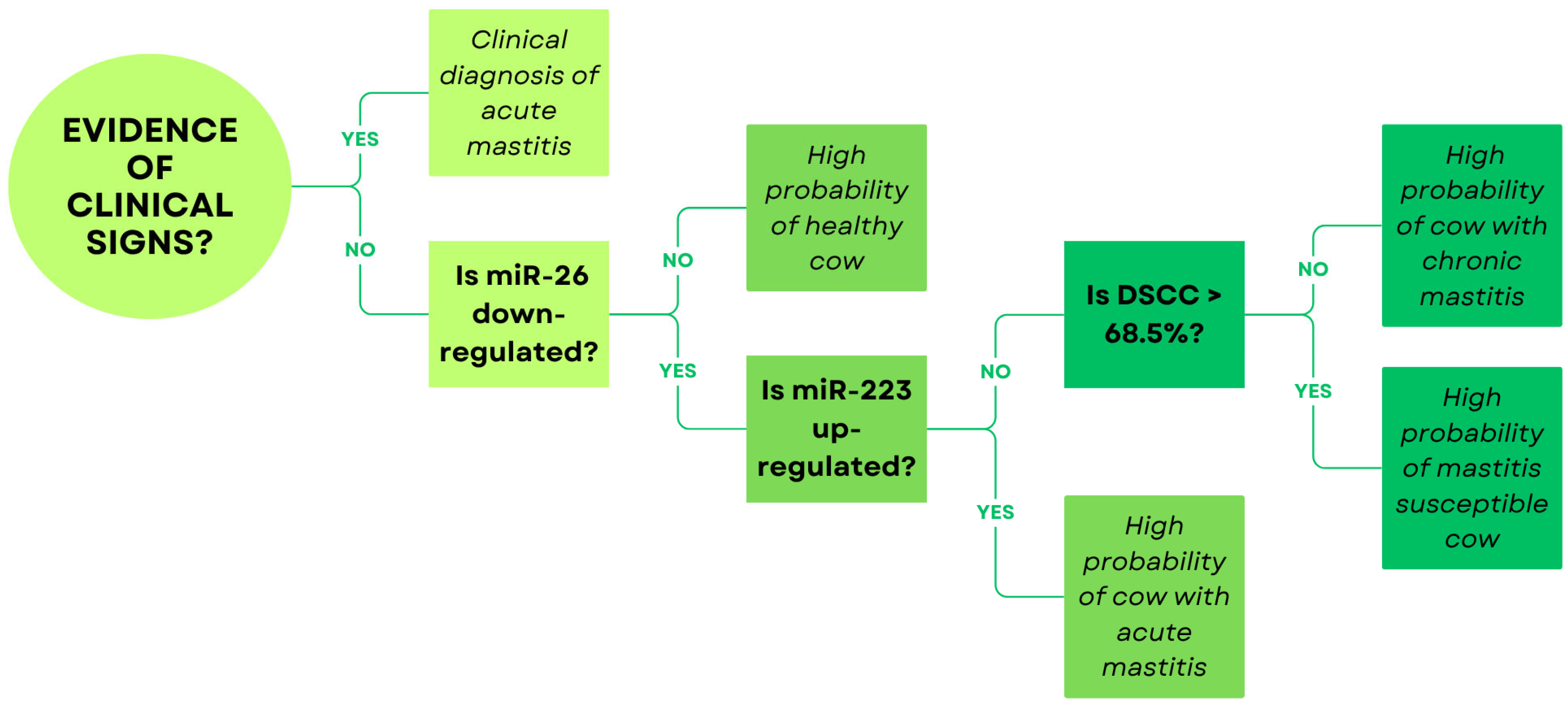

5.3.3. Concluding Remarks on Molecular Biomarkers

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| aDCT | Antibiotic dry cow therapy |

| S. aureus | Staphylococcus aureus |

| S. agalactiae | Streptococcus agalactiae |

| E. coli | Escherichia coli |

| SCC | Somatic cell count |

| CMT | California mastitis test |

| miRNA | MicroRNA |

| LTF | Lactoferrin |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| Hp | Haptoglobin |

| AGP | α-1-acid glycoprotein |

| SAA | Serum amyloid A |

| MAA | Milk amyloid A |

| DEFB4 | β-defensin 4 |

| PMECs | Primary mammary epithelial cells |

| PON1 | Paraoxonase 1 |

| HDL | High-density lipoprotein |

| NAGase | N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase |

| BLG | β-lactoglobulin |

| DAMPs | Damage-associated molecular patterns |

| mtDNA | Mitochondrial DNA |

| DSCC | Differential somatic cell count |

| CM | Clinical mastitis |

| SCM | Subclinical mastitis |

| EIM | Experimentally induced mastitis |

References

- Raboisson, D.; Barbier, M.; Maigné, E. How Metabolic Diseases Impact the Use of Antimicrobials: A Formal Demonstration in the Field of Veterinary Medicine. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerto, M.A.; Shepley, E.; Cue, R.I.; Warner, D.; Dubuc, J.; Vasseur, E. The hidden cost of disease: I. Impact of the first incidence of mastitis on production and economic indicators of primiparous dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 7932–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtolainen, T.; Røntved, C.; Pyörälä, S. Serum amyloid A and TNF alpha in serum and milk during experimental endotoxin mastitis. Vet. Res. 2004, 35, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antanaitis, R.; Juozaitienė, V.; Jonike, V.; Baumgartner, W.; Paulauskas, A. Milk lactose as a biomarker of subclinical mastitis in dairy cows. Animals 2021, 11, 1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharun, K.; Dhama, K.; Tiwari, R.; Gugjoo, M.B.; Iqbal Yatoo, M.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Karthik, K.; Khurana, S.K.; Singh, R.; et al. Advances in therapeutic and managemental approaches of bovine mastitis: A comprehensive review. Vet. Q. 2021, 41, 107–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hogeveen, H.; Steeneveld, W.; Wolf, C.A. Production diseases reduce the efficiency of dairy production: A review of the results, methods, and approaches regarding the economics of mastitis. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lacasse, P. Mammary tissue damage during bovine mastitis: Causes and control. J. Anim. Sci. 2008, 86, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruegg, P.L. A 100-Year Review: Mastitis detection, management, and prevention. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 10381–10397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huszenicza, G.; Jánosi, S.; Kulcsár, M.; Kóródi, P.; Reiczigel, J.; Kátai, L.; Peters, A.R.; De Rensis, F. Effects of clinical mastitis on ovarian function in post-partum dairy cows. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2005, 40, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavon, Y.; Kaim, M.; Leitner, G.; Biran, D.; Ezra, E.; Wolfenson, D. Two approaches to improve fertility of subclinical mastitic dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, J.M. Mastitis—The struggle for understanding. J. Dairy Sci. 1956, 39, 17–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, R.E.; Hovinen, M.; Rajala-Schultz, P.J. Selective dry cow therapy effect on milk yield and somatic cell count: A retrospective cohort study. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 1387–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.; Kabera, F.; Dufour, S.; Godden, S.; Roy, J.P.; Nydam, D. Selective dry-cow therapy can be implemented successfully in cows of all milk production levels. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 1953–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odegård, J.; Klemetsdal, G.; Heringstad, B. Genetic improvement of mastitis resistance: Validation of somatic cell score and clinical mastitis as selection criteria. J. Dairy Sci. 2003, 86, 4129–4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikonen, T.; Morri, S.; Tyrisevä, A.M.; Ruottinen, O.; Ojala, M. Genetic and phenotypic correlations between milk coagulation properties, milk production traits, somatic cell count, casein content, and pH of milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2004, 87, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, D.; Stamer, E.; Junge, W.; Kalm, E. Genetic analyses of mastitis data using animal threshold models and genetic correlation with production traits. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 2260–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heringstad, B.; Gianola, D.; Chang, Y.M.; Odegård, J.; Klemetsdal, G. Genetic associations between clinical mastitis and somatic cell score in early first-lactation cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 2236–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cha, E.; Hertl, J.; Schukken, Y.; Tauer, L.; Welcome, F.; Gröhn, Y. Evidence of no protection for a recurrent case of pathogen specific clinical mastitis from a previous case. J. Dairy Res. 2016, 83, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, R.; Prenafeta, A.; González-González, L.; Pérez-Pons, J.A.; Sitjà, M. Probing vaccine antigens against bovine mastitis caused by Streptococcus uberis. Vaccine 2016, 34, 3848–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misra, N.; Wines, T.F.; Knopp, C.L.; Hermann, R.; Bond, L.; Mitchell, B.; McGuire, M.A.; Tinker, J.K. Immunogenicity of a Staphylococcus aureus-cholera toxin A2/B vaccine for bovine mastitis. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3513–3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhylkaidar, A.; Oryntaev, K.; Altenov, A.; Kylpybai, E.; Chayxmet, E. Prevention of Bovine Mastitis through Vaccination. Arch. Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 1381–1387. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, W.N.; Han, S.G. Bovine mastitis: Risk factors, therapeutic strategies, and alternative treatments—A review. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 33, 1699–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannerman, D.D.; Paape, M.J.; Lee, J.W.; Zhao, X.; Hope, J.C.; Rainard, P. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus elicit differential innate immune responses following intramammary infection. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 2004, 11, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Freu, G.; Garcia, B.L.N.; Tomazi, T.; Di Leo, G.S.; Gheller, L.S.; Bronzo, V.; Moroni, P.; Dos Santos, M.V. Association between Mastitis Occurrence in Dairy Cows and Bedding Characteristics of Compost-Bedded Pack Barns. Pathogens 2023, 12, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rambeaud, M.; Almeida, R.A.; Pighetti, G.M.; Oliver, S.P. Dynamics of leukocytes and cytokines during experimentally induced Streptococcus uberis mastitis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2003, 96, 193–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petzl, W.; Zerbe, H.; Günther, J.; Yang, W.; Seyfert, H.M.; Nürnberg, G.; Schuberth, H.J. Escherichia coli, but not Staphylococcus aureus triggers an early increased expression of factors contributing to the innate immune defense in the udder of the cow. Vet. Res. 2008, 39, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genini, S.; Badaoui, B.; Sclep, G.; Bishop, S.C.; Waddington, D.; Pinard van der Laan, M.H.; Klopp, C.; Cabau, C.; Seyfert, H.M.; Petzl, W.; et al. Strengthening insights into host responses to mastitis infection in ruminants by combining heterogeneous microarray data sources. BMC Genom. 2011, 12, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.S.; Koo, H.C.; Joo, Y.S.; Jeon, S.H.; Hur, D.S.; Chung, C.I.; Jo, H.S.; Park, Y.H. Application of a new portable microscopic somatic cell counter with disposable plastic chip for milk analysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2253–2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piccinini, R.; Binda, E.; Belotti, M.; Casirani, G.; Zecconi, A. Comparison of blood and milk non-specific immune parameters in heifers after calving in relation to udder health. Vet. Res. 2005, 36, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, J.M.; Hawkins, D.M.; Kinsel, M.L.; Reneau, J.K. Bulk tank somatic cell counts analyzed by statistical process control tools to identify and monitor subclinical mastitis incidence. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 3944–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valldecabres, A.; Clabby, C.; Dillon, P.; Silva Boloña, P. Association between quarter-level milk somatic cell count and intramammary bacterial infection in late-lactation Irish grazing dairy cows. JDS Commun. 2023, 4, 274–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zecconi, A.; Vairani, D.; Cipolla, M.; Rizzi, N.; Zanini, L. Assessment of subclinical mastitis diagnostic accuracy by differential cell count in individual cow milk. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2019, 18, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhussien, M.N.; Dang, A.K. Milk somatic cells, factors influencing their release, future prospects, and practical utility in dairy animals: An overview. Vet. World 2018, 11, 562–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mondini, S.; Gislon, G.; Zucali, M.; Sandrucci, A.; Tamburini, A.; Bava, L. Factors influencing somatic cell count and leukocyte composition in cow milk: A field study. J. Dairy Sci. 2025, 108, 2721–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, S.; Dhama, K.; Tiwari, R.; Iqbal Yatoo, M.; Khurana, S.K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Munuswamy, P.; Kumar, M.A.; Singh, M.; et al. Technological interventions and advances in the diagnosis of intramammary infections in animals with emphasis on bovine population—A review. Vet. Q. 2019, 39, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalm, O.W.; Noorlander, D.O. Experiments and observations leading to development of the California mastitis test. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1957, 130, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sanford, C.J.; Keefe, G.P.; Sanchez, J.; Dingwell, R.T.; Barkema, H.W.; Leslie, K.E.; Dohoo, I.R. Test characteristics from latent-class models of the California Mastitis Test. Prev. Vet. Med. 2006, 77, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepe, M.S.; Feng, Z.; Janes, H.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Potter, J.D. Pivotal evaluation of the accuracy of a biomarker used for classification or prediction: Standards for study design. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008, 100, 1432–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Devanarayan, V.; Barrett, Y.C.; Weiner, R.; Allinson, J.; Fountain, S.; Keller, S.; Weinryb, I.; Green, M.; Duan, L.; et al. Fit-for-purpose method development and validation for successful biomarker measurement. Pharm. Res. 2006, 23, 312–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.C.; Waterston, M.; Hastie, P.; Parkin, T.; Haining, H.; Eckersall, P.D. The major acute phase proteins of bovine milk in a commercial dairy herd. BMC Vet. Res. 2015, 11, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoreng, Z.M.; Wang, X.P.; Mei, C.G.; Zan, L.S. Comparison of microRNA profiles between bovine mammary glands infected with Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 14, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luoreng, Z.M.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.P.; Wei, D.W.; Zan, L.S. Expression Profiling of microRNA From Peripheral Blood of Dairy Cows in Response to Staphylococcus aureus-Infected Mastitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 691196. [Google Scholar]

- Dall’Olio, E.; De Rensis, F.; Martignani, E.; Miretti, S.; Ala, U.; Cavalli, V.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Andrani, M.; Baratta, M.; Saleri, R. Differential Expression of miR-223-3p and miR-26-5p According to Different Stages of Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 235. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, S.; Siegert, S.; Fischer, A. β-defensin-4 as an endogenous biomarker in cows with mastitis. Front. Vet. Sci. 2023, 10, 1154386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedić, S.; Vakanjac, S.; Samardžija, M.; Borozan, S. Paraoxonase 1 in bovine milk and blood as marker of subclinical mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 125, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Leishangthem, G.D.; Singh, N.K.; Singh, N.D.; Filia, G.; Singh, A. Cell free mitochondrial DNA in serum and milk associated with bovine mastitis: A pilot study. Vet. Res. Commun. 2018, 42, 275–282. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, A.; Kulangara, V.; Vareed, T.P.; Melepat, D.P.; Chattothayil, L.; Chullipparambil, S. Variations in the levels of acute-phase proteins and lactoferrin in serum and milk during bovine subclinical mastitis. J. Dairy Res. 2021, 88, 321–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, R.; Piras, C.; Kovačić, M.; Samardžija, M.; Ahmed, H.; De Canio, M.; Urbani, A.; Meštrić, Z.F.; Soggiu, A.; Bonizzi, L.; et al. Proteomics of inflammatory and oxidative stress response in cows with subclinical and clinical mastitis. J. Proteom. 2012, 75, 4412–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galfi, A.L.; Radinović, M.Ž.; Boboš, S.F.; Pajić, M.J.; Savić, S.S.; Milanov, D.S. Lactoferrin concentrations in bovine milk during involution of the mammary glands, with different bacteriological findings. Vet. Arh. 2016, 86, 487–497. [Google Scholar]

- Musayeva, K.; Sederevičius, A.; Zelvyte, R.; Monkevičiene, I.; Beliavska-Aleksiejune, D.; Kerziene, S. Concentration of lactoferrin and immunoglobulin G in cows’ milk in relation to health status of the udder, lactation and season. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2016, 19, 737–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.A.; El-Razik, K.A.E.H.A.; Gomaa, A.M.; Elbayoumy, M.K.; Abdelrahman, K.A.; Hosein, H.I. Milk amyloid A as a biomarker for diagnosis of subclinical mastitis in cattle. Vet. World 2018, 11, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovinen, M.; Simojoki, H.; Pösö, R.; Suolaniemi, J.; Kalmus, P.; Suojala, L.; Pyörälä, S. N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminidase activity in cow milk as an indicator of mastitis. J. Dairy Res. 2016, 83, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolenski, G.A.; Wieliczko, R.J.; Pryor, S.M.; Broadhurst, M.K.; Wheeler, T.T.; Haigh, B.J. The abundance of milk cathelicidin proteins during bovine mastitis. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2011, 143, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, U.; Deb, R.; Kumar, S.; Singh, R.; Sengar, G.; Sharma, A. Association of prolactin and beta-lactoglobulin genes with milk production traits and somatic cell count among Indian Frieswal (HF × Sahiwal) cows. Biomark. Genom. Med. 2015, 7, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musayeva, K.; Sederevičius, A.; Želvytė, R.; Monkevičienė, I.; Beliavska-Aleksiejūnė, D.; Garbenytė, Ž. Lactoferrin and immunoglobulin g content in cow milk in relation to somatic cell count and number of lactations. Vet. Med. Zoot 2018, 76, 98. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, S.I.; Kawai, K.; Anri, A.; Nagahata, H. Lactoferrin Concentrations in Milk from Normal and Subclinical Mastitic Cows. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2003, 65, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, S.; Javed, Q.; Blumenberg, M. Meta-analysis of transcriptional responses to mastitis-causing Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0148562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodowska, P.; Zwierzchowski, L.; Marczak, S.; Jarmuż, W.; Bagnicka, E. Associations between bovine β-defensin 4 genotypes and production traits of polish holstein-friesian dairy cattle. Animals 2019, 9, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, S.; Lang, A.; Rohde, M.; Agarwal, V.; Rennemeier, C.; Grashoff, C.; Preissner, K.T.; Hammerschmidt, S. Integrin-linked kinase is required for vitronectin-mediated internalization of Streptococcus pneumoniae by host cells. J. Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 256–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, B.K.; Hamann, J.; Grabowski, N.T.; Singh, K.B. Variation in the composition of selected milk fraction samples from healthy and mastitic quarters, and its significance for mastitis diagnosis. J. Dairy Res. 2005, 72, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyörälä, S.; Hovinen, M.; Simojoki, H.; Fitzpatrick, J.; Eckersall, P.D.; Orro, T. Acute phase proteins in milk in naturally acquired bovine mastitis caused by different pathogens. Vet. Rec. 2011, 168, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirala, N.R.; Shtenberg, G. Bovine mastitis inflammatory assessment using silica coated ZnO-NPs induced fluorescence of NAGase biomarker assay. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 257, 119769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongthaisong, P.; Katawatin, S.; Thamrongyoswittayakul, C.; Roytrakul, S. Milk protein profiles in response to Streptococcus agalactiae subclinical mastitis in dairy cows. Anim. Sci. J. 2016, 87, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addis, M.F.; Bronzo, V.; Puggioni, G.M.G.; Cacciotto, C.; Tedde, V.; Pagnozzi, D.; Locatelli, C.; Casula, A.; Curone, G.; Uzzau, S.; et al. Relationship between milk cathelicidin abundance and microbiologic culture in clinical mastitis. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 2944–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puppel, K.; Kalińska, A.; Kot, M.; Slósarz, J.; Kunowska-Slósarz, M.; Grodkowski, G.; Kuczyńska, B.; Solarczyk, P.; Przysucha, T.; Gołębiewski, M. The effect of Staphylococcus spp., Streptococcus spp. and Enterobacteriaceae on the development of whey protein levels and oxidative stress markers in cows with diagnosed mastitis. Animals 2020, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alim, M.A.; Sun, D.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, L. DNA Polymorphisms in the lactoglobulin ans K-casein Gense Associated with Milk Production Traits on Dairy Cattle. Bioresearch Commun. 2015, 1, 82–86. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, A.; Lopez-Villalobos, N.; Sneddon, N.W.; Shalloo, L.; Franzoi, M.; De Marchi, M.; Penasa, M. Invited review: Milk lactose—Current status and future challenges in dairy cattle. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5883–5898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cant, J.P.; Trout, D.R.; Qiao, F.; Purdie, N.G. Milk synthetic response of the bovine mammary gland to an increase in the local concentration of arterial glucose. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobbo, T.; Ruegg, P.L.; Stocco, G.; Fiore, E.; Gianesella, M.; Morgante, M.; Pasotto, D.; Bittante, G.; Cecchinato, A. Associations between pathogen-specific cases of subclinical mastitis and milk yield, quality, protein composition, and cheese-making traits in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 4868–4883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, L.M.; Shook, G.E. Prediction of Mastitis Using Milk Somatic Cell Count, N-Acetyl-β-D-Glucosaminidase, and Lactose. J. Dairy Sci. 1992, 75, 1840–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilde, C.J.; Addey, C.V.P.; Peaker, M. Effects of immunization against an autocrine inhibitor of milk secretion in lactating goats. J. Physiol. 1996, 491, 465–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, A.N.; Czajka, A. Is mitochondrial DNA content a potential biomarker of mitochondrial dysfunction? Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miretti, S.; Martignani, E.; Taulli, R.; Bersani, F.; Accornero, P.; Baratta, M. Differential expression of microRNA-206 in skeletal muscle of female Piedmontese and Friesian cattle. Vet. J. 2011, 190, 412–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tewari, R.S.; Ala, U.; Accornero, P.; Baratta, M.; Miretti, S. Circulating skeletal muscle related microRNAs profile in Piedmontese cattle during different age. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.W.; Shen, Y.J.; Shi, J.; Yu, J.G. MiR-223-3p in Cardiovascular Diseases: A Biomarker and Potential Therapeutic Target. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 7, 610561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.C.; Fujikawa, T.; Maemura, T.; Ando, T.; Kitahara, G.; Endo, Y.; Yamato, O.; Koiwa, M.; Kubota, C.; Miura, N. Inflammation-related microRNA expression level in the bovine milk is affected by mastitis. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0177182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheedy, F.J.; Palsson-McDermott, E.; Hennessy, E.J.; Martin, C.; O’Leary, J.J.; Ruan, Q.; Johnson, D.S.; Chen, Y.; O’Neill, L.A. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taganov, K.D.; Boldin, M.P.; Chang, K.J.; Baltimore, D. NF-kappaB-dependent induction of microRNA miR-146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12481–12486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.P.; Luoreng, Z.M.; Zan, L.S.; Raza, S.H.A.; Li, F.; Li, N.; Liu, S. Expression patterns of miR-146a and miR-146b in mastitis infected dairy cattle. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2016, 30, 342–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzelos, T.; Ho, W.; Charmana, V.I.; Lee, S.; Donadeu, F.X. MiRNAs in milk can be used towards early prediction of mammary gland inflammation in cattle. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srikok, S.; Patchanee, P.; Boonyayatra, S.; Chuammitri, P. Potential role of MicroRNA as a diagnostic tool in the detection of bovine mastitis. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 182, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocco, G.; Summer, A.; Cipolat-Gotet, C.; Zanini, L.; Vairani, D.; Dadousis, C.; Zecconi, A. Differential Somatic Cell Count as a Novel Indicator of Milk Quality in Dairy Cows. Animals 2020, 10, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, Y.C.; Habiby, G.H.; Jasing Pathiranage, C.C.; Rahman, M.M.; Chen, H.W.; Husna, A.A.; Kubota, C.; Miura, N. Bovine serum miR-21 expression affected by mastitis. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021, 135, 290–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample | Marker | Mastitis | Molecule | Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk and serum | PR | SCM | DEFB4 | Down | [44] |

| PR | SCM | PON1 | Down | [45] | |

| MO | SCM | mtDNA | Over | [46] | |

| Serum | PR | SCM | SAA | Over | [47] |

| PR | CM | DEFB4 | Over | [44] | |

| PR | CM, SCM | Vitronectin | Over | [48] | |

| Milk | PR | CM, SCM | LTF | Over | [49] |

| PR | CM, SCM | IgG | Over | [50] | |

| PR | SCM | Hp and AGP | Over | [47] | |

| PR | SCM | MAA | Over | [51] | |

| PR | CM, SCM | NAGase | Over | [52] | |

| PR | CM, SCM | Cathelicidins | Over | [53] | |

| GL | SCM | Lactose | Down | [4] | |

| PR | CM, SCM | BLG | Down | [54] |

| Healthy (mg/mL) | Subclinical Mastitis (mg/mL) | Method of Detection | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.1 ± 0.02 | ELISA kit (Biopanda Reagents, Belfast, UK) | [50] |

| 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA) | [55] |

| 5.12 ± 1.77 | 5.45 ± 1.68 (major mastitis pathogens) | ELISA kit (Bethyl Laboratories Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA) | [49] |

| 5.95 ± 1.65 (minor mastitis pathogens) | |||

| ~0.25 ± 0.04 | ~0.84 ± 0.15 | ELISA kit (Life Diagnostics, West Chester, PA, USA) | [47] |

| Sample | Mastitis | MiRNA | Expression | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milk | CM, SCM | miR-21 | Up | [76] |

| miR-146a | Up | |||

| miR-155 | Up | |||

| miR-222 | Up | |||

| miR-383 | Up | |||

| Serum | CM, SCM | miR-21 | Up | [83] |

| Milk | EIM (E. coli) | miR-144, miR-451 | Down | [41] |

| EIM (S. aureus) | miR-144, miR-451 | Up | ||

| EIM (E. coli, S. aureus) | miR-7863 | Up | ||

| Blood | EIM (S. aureus) | miR-1301 | Up | [42] |

| EIM (S. aureus) | miR-2284r | Down | ||

| Skim milk | CM, SCM | miR-29b-2 | Up | [81] |

| miR-184 | Up | |||

| miR-146a | Down | |||

| miR-148a | Down | |||

| miR-155 | Down | |||

| Milk | SCM | miR-142-5p | Up | [80] |

| miR-146a | Up | |||

| miR-223 | Up | |||

| Milk | CM, SCM | miR-26 | Up | [43] |

| miR-223 | Up |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dall’Olio, E.; Andrani, M.; Baratta, M.; Rensis, F.D.; Saleri, R. Functional Role and Diagnostic Potential of Biomarkers in the Early Detection of Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Animals 2026, 16, 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020159

Dall’Olio E, Andrani M, Baratta M, Rensis FD, Saleri R. Functional Role and Diagnostic Potential of Biomarkers in the Early Detection of Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Animals. 2026; 16(2):159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020159

Chicago/Turabian StyleDall’Olio, Eleonora, Melania Andrani, Mario Baratta, Fabio De Rensis, and Roberta Saleri. 2026. "Functional Role and Diagnostic Potential of Biomarkers in the Early Detection of Mastitis in Dairy Cows" Animals 16, no. 2: 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020159

APA StyleDall’Olio, E., Andrani, M., Baratta, M., Rensis, F. D., & Saleri, R. (2026). Functional Role and Diagnostic Potential of Biomarkers in the Early Detection of Mastitis in Dairy Cows. Animals, 16(2), 159. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16020159