Molecular Characterization and Functional Insights into Goose IGF2BP2 During Skeletal Muscle Development

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. RNA Extraction, DNA Isolation, and cDNA Synthesis

2.3. Molecular Cloning and Sequence Analysis of Goose IGF2BP2 Gene

2.4. Identification of Genetic Variants

2.5. Tissue-Specific Expression Profiling of Goose IGF2BP2 mRNA

2.6. Isolation and Culture of Goose SMSCs

2.7. Plasmid Construction, Lentiviral Production, and Cell Transduction

2.8. Library Preparation and Transcriptome Analysis

2.9. Validation of DEG Results by qRT-PCR

2.10. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

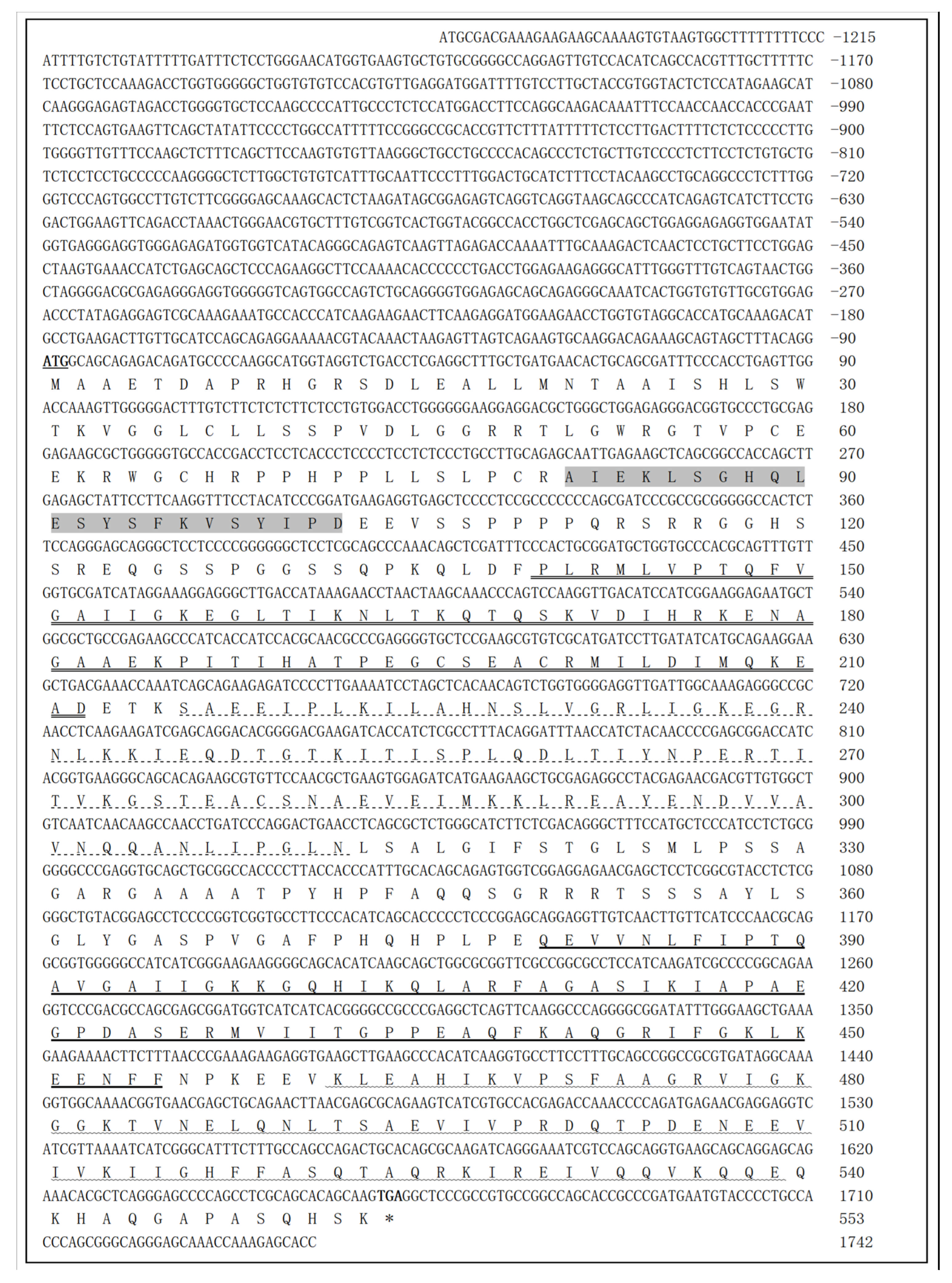

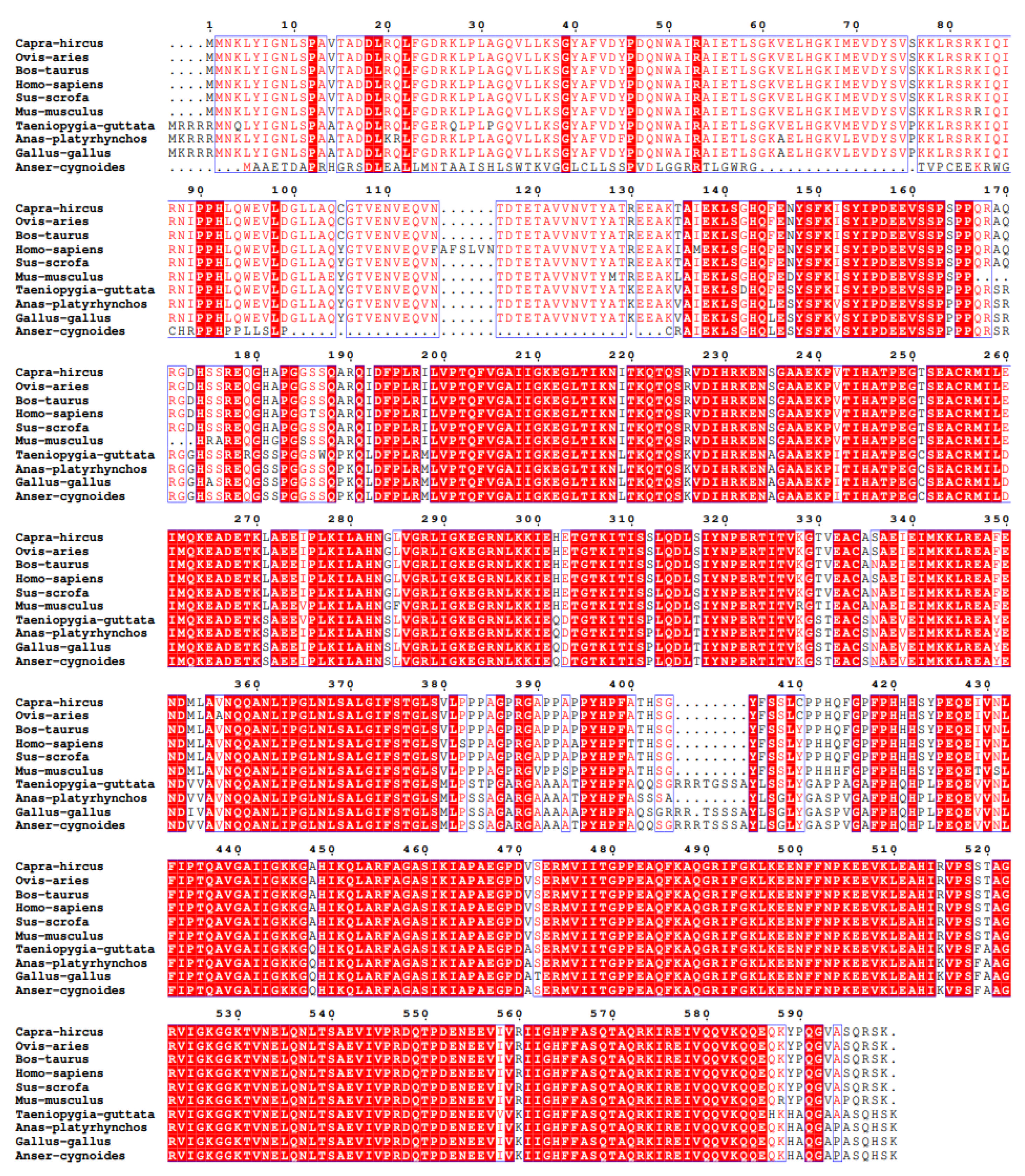

3.1. cDNA Sequence Analysis of Goose IGF2BP2 Gene

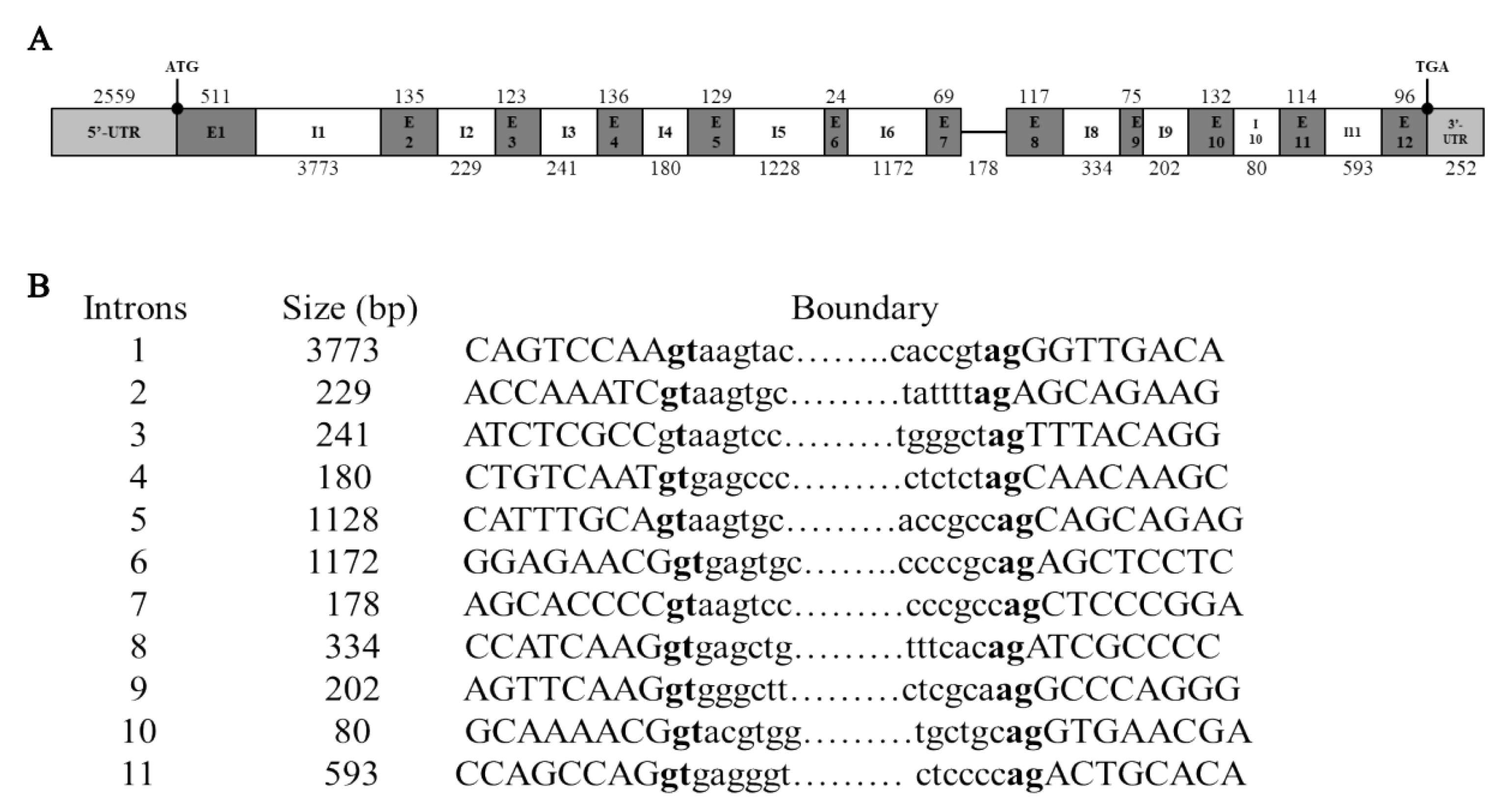

3.2. Genomic Organization and SNP Survey of Goose IGF2BP2

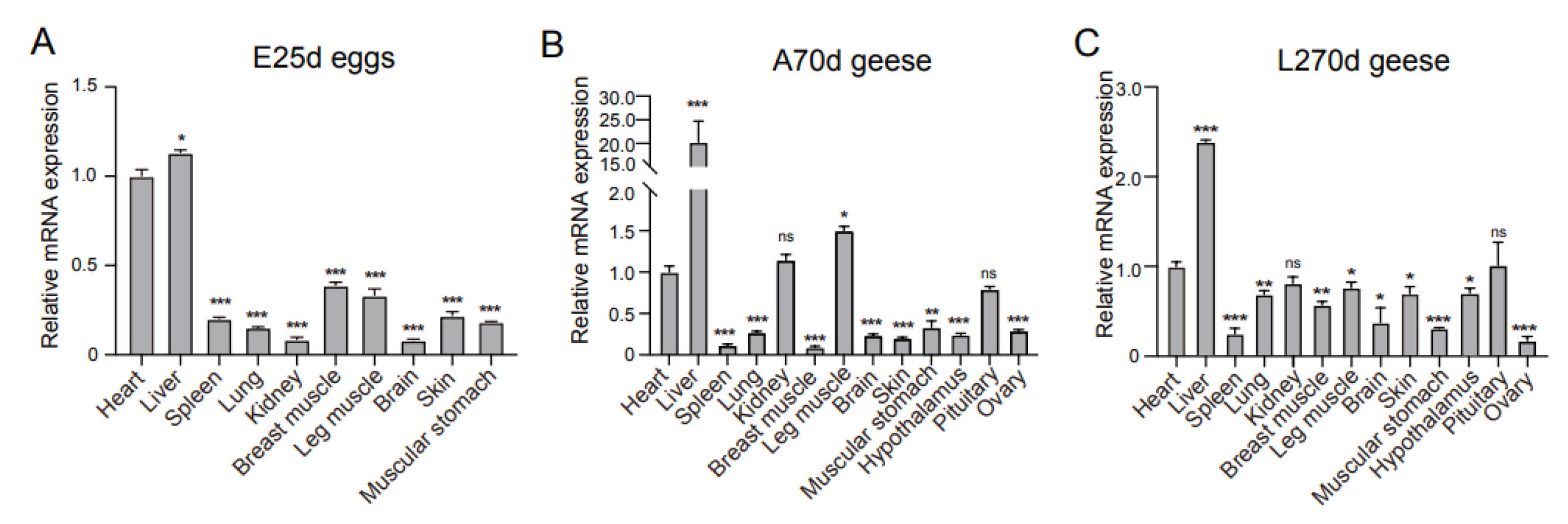

3.3. Tissue Expression Profile of IGF2BP2 mRNA in ZW Geese

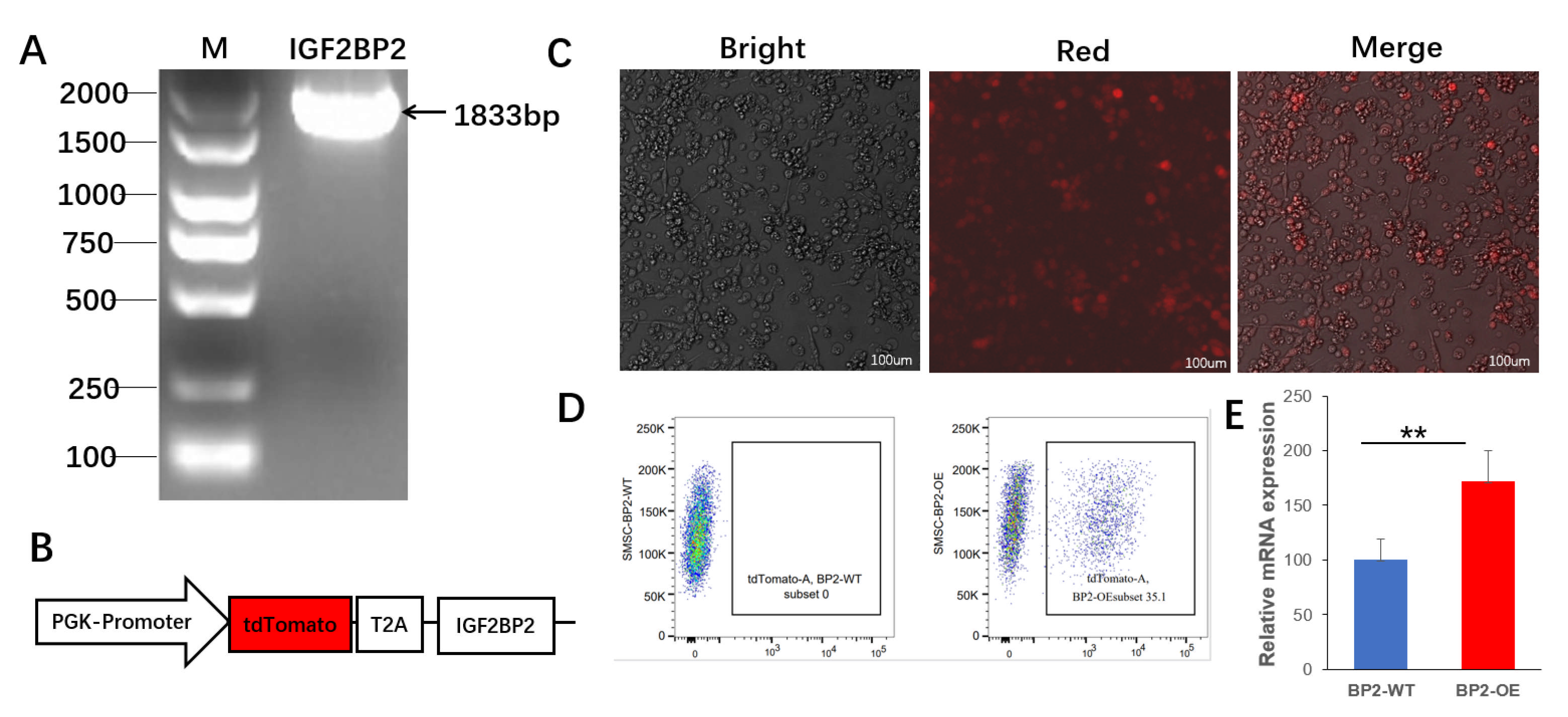

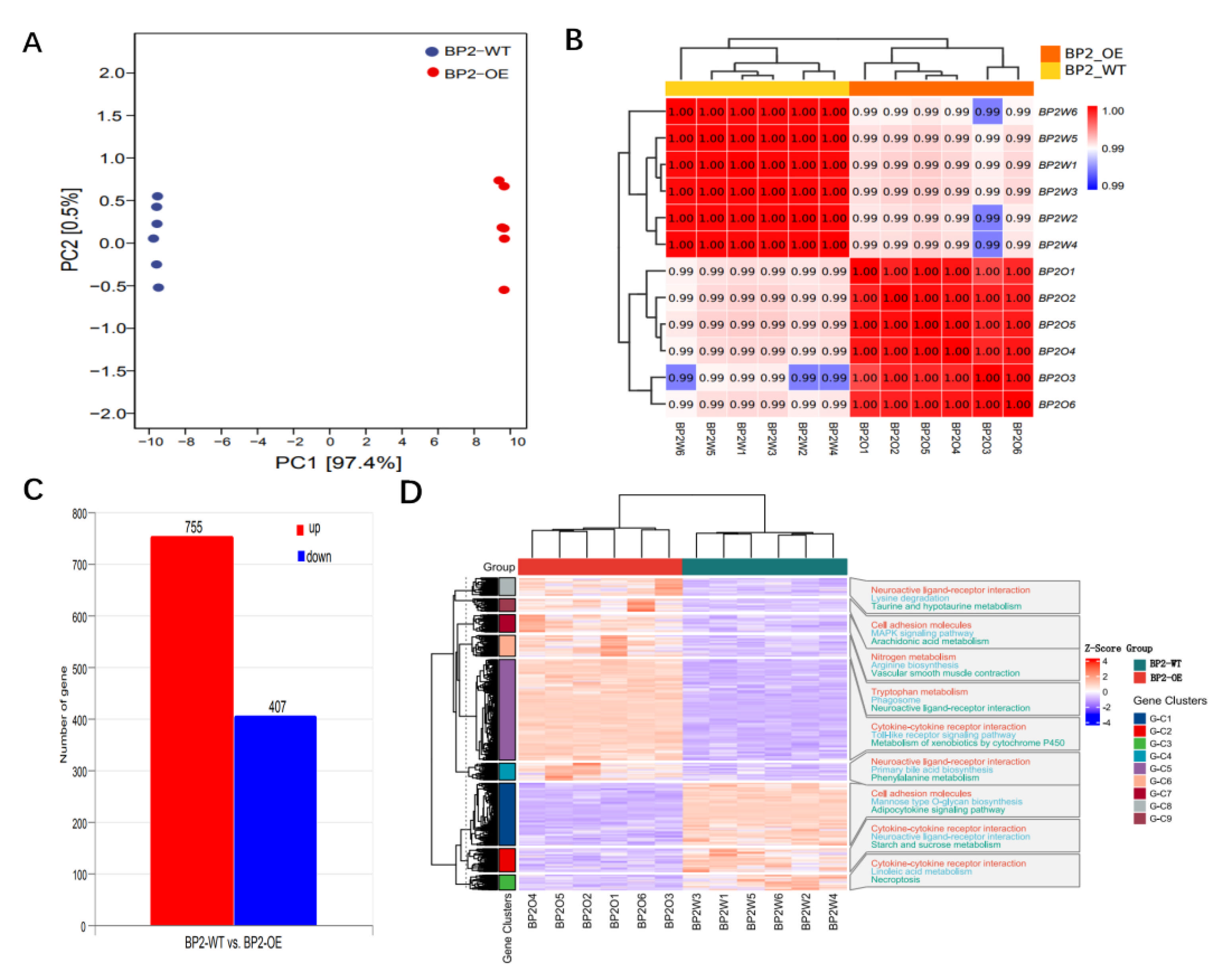

3.4. Gene Expression Analysis of IGF2BP2-Overexpressed Cells

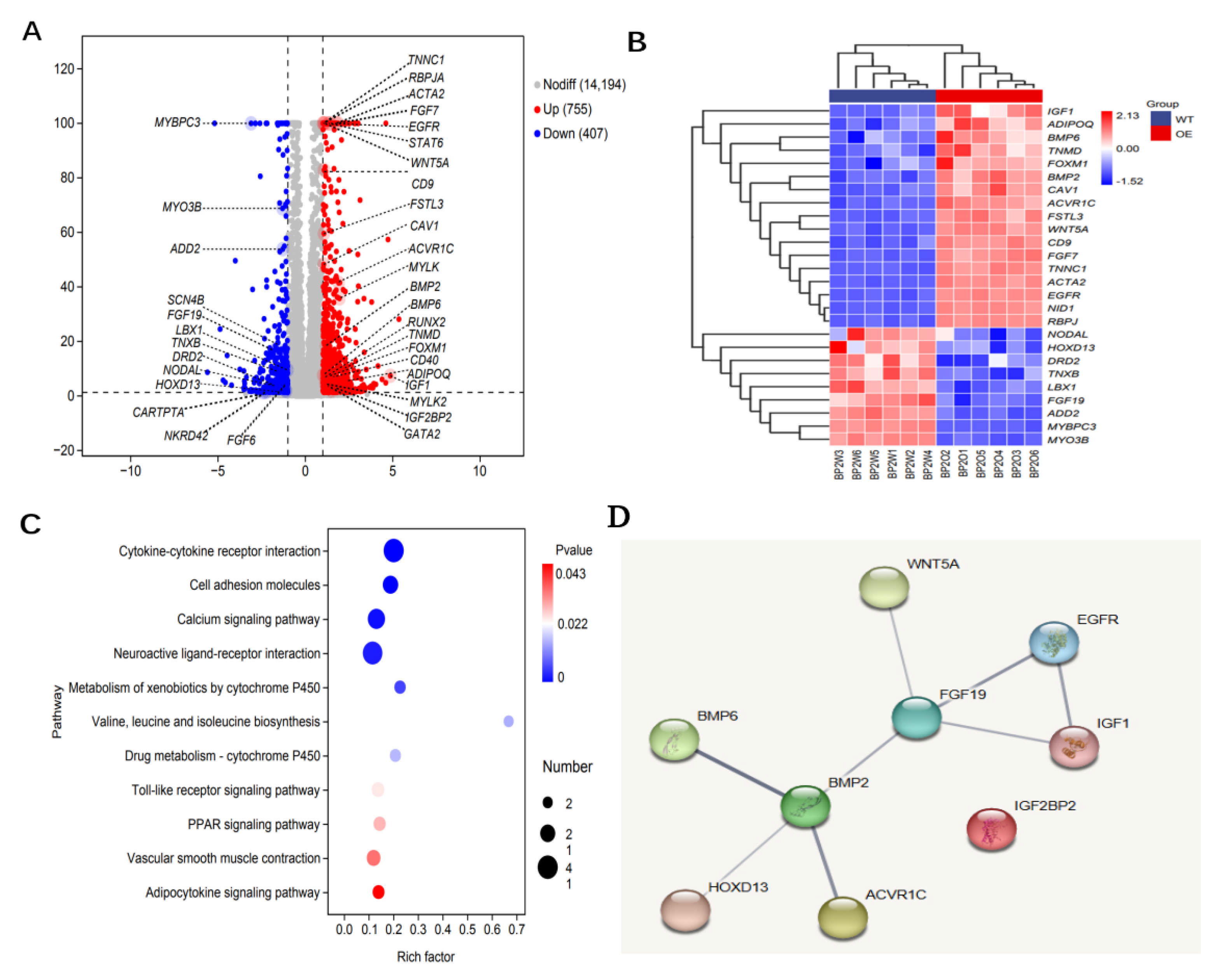

3.5. Identification of Key Genes Associated with SMSCs Development

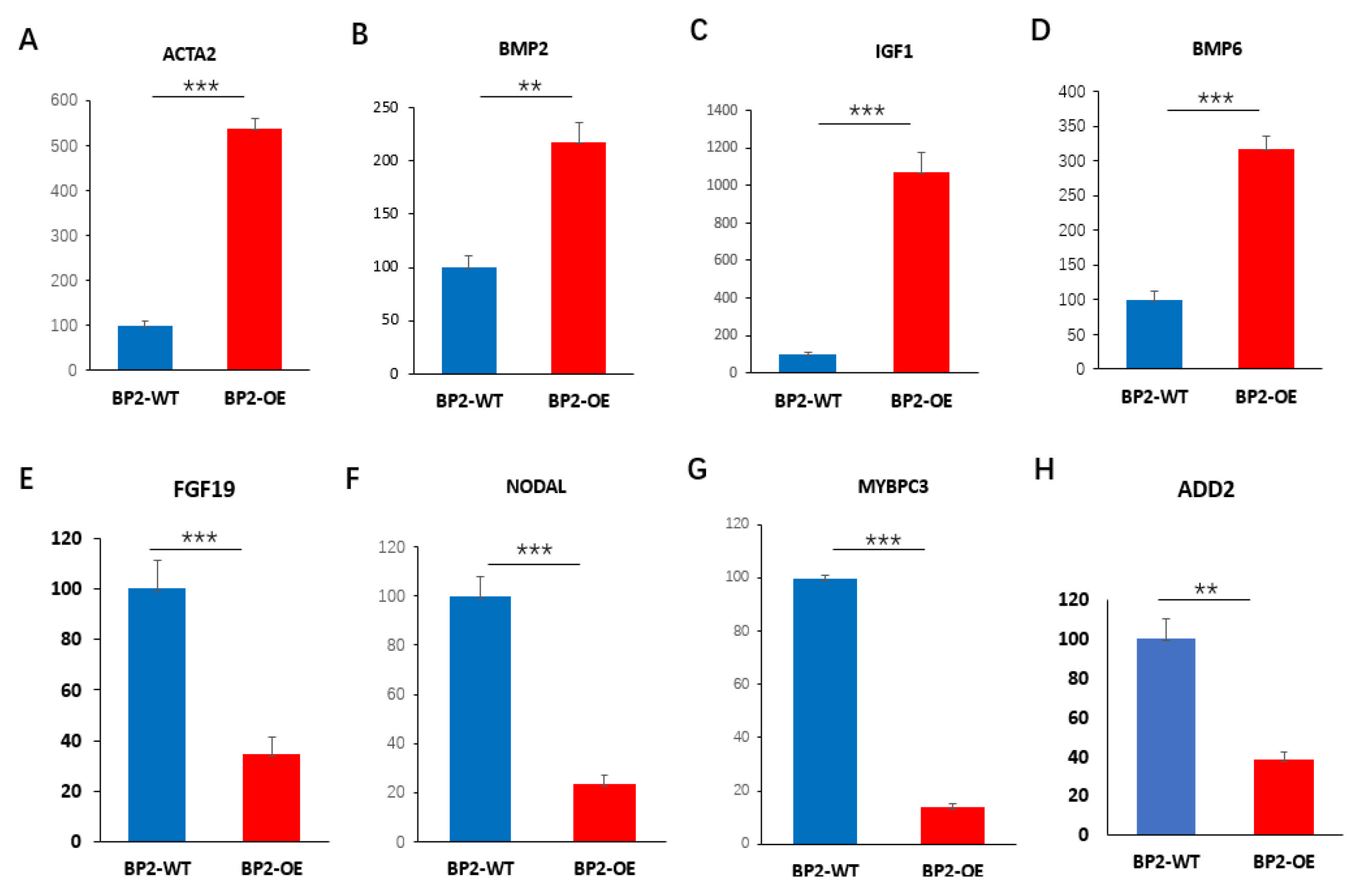

3.6. Validation of DEGs by qPCR

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Stöhr, N.; Köhn, M.; Lederer, M.; Glass, M.; Reinke, C.; Singer, R.H.; Hüttelmaier, S. IGF2BP1 promotes cell migration by regulating MK5 and PTEN signaling. Genes Dev. 2012, 26, 176–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, M.; Cheng, H.; Fan, W.; Yuan, Z.; Gao, Q.; Xu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; et al. An intercross population study reveals genes associated with body size and plumage color in ducks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Gowda, C.P.; Singh, V.; Ganapathy, A.S.; Karamchandani, D.M.; Eshelman, M.A.; Yochum, G.S.; Nighot, P.; Spiegelman, V.S. The mRNA-binding protein IGF2BP1 maintains intestinal barrier function by up-regulating occludin expression. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 8602–8612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Weng, H.; Sun, W.; Qin, X.; Shi, H.; Wu, H.; Zhao, B.S.; Mesquita, A.; Liu, C.; Yuan, C.L.; et al. Recognition of RNA N6-methyladenosine by IGF2BP proteins enhances mRNA stability and translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, N.; Zhao, L.; Wrighting, D.; Krämer, D.; Majithia, A.; Wang, Y.; Cracan, V.; Borges-Rivera, D.; Mootha, V.K.; Nahrendorf, M.; et al. IGF2BP2/IMP2-Deficient mice resist obesity through enhanced translation of Ucp1 mRNA and other mRNAs encoding mitochondrial proteins. Cell Metab. 2015, 21, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Li, Z.; Ramanujan, K.; Clay, I.; Zhang, Y.; Lemire-Brachat, S.; Glass, D.J. A long non-coding RNA, LncMyoD, regulates skeletal muscle differentiation by blocking IMP2-mediated mRNA translation. Dev. Cell 2015, 34, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Gilbert, J.A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Qiu, Q.; Ramanujan, K.; Shavlakadze, T.; Eash, J.K.; Scaramozza, A.; Goddeeris, M.M.; et al. An HMGA2-IGF2BP2 axis regulates myoblast proliferation and myogenesis. Dev. Cell 2012, 23, 1176–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Li, M.; Huang, H.; Chen, K.; Yuan, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Nie, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, L.; et al. HMGB2 regulates satellite-cell-mediated skeletal muscle regeneration through IGF2BP2. J. Cell Sci. 2016, 129, 4305–4316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, D.; Bai, Y.; Bi, Y.; He, L.; Kang, Y.; Pan, C.; Zhu, H.; Chen, H.; Qu, L.; Lan, X. Insertion/deletion variants within the IGF2BP2 gene identified in reported genome-wide selective sweep analysis reveal a correlation with goat litter size. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. 2021, 22, 757–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Q.; Zhang, G.; Li, T.; Ling, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J. Transcriptomic profile of leg muscle during early growth in chicken. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.E.; Huang, K.; Gibril, B.A.A.; Xiong, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J. Identification of Novel Genetic Loci Involved in Testis Traits of the Jiangxi Local Breed Based on GWAS Analyses. Genes 2015, 16, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Lin, B.; Yan, Z.; Tong, Y.; Liu, H.; He, X.; Zhang, H. Phenotypic Identification, Genetic Characterization, and Selective Signal Detection of Huitang Duck. Animals 2024, 14, 1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Lin, S.; Gu, L.; Lu, L.; Liao, Z.; Peng, Q.; Zhang, L. Research note: Detection of IGF2BP2 gene polymorphism associated with growth and reproduction traits of pigeon. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, F.Y.; Chang, K.C.; Chang, C.S.; Wang, P.H. Development of a Rapid Sex Identification Method for Newborn Pigeons Using Recombinase Polymerase Amplification and a Lateral-Flow Dipstick on Farm. Animals 2022, 12, 2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Dai, J.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; He, D. Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Role of the FST Gene in Goose Muscle Development. Animals 2025, 15, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISATgenotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, S.; Pyl, P.T.; Huber, W. HTSeq-a Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2014, 31, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Williams, B.A.; Pertea, G.; Mortazavi, A.; Kwan, G.; van Baren, M.J.; Salzberg, S.L.; Wold, B.J.; Pachter, L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Feng, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, X. DEGseq: An R package for identifying differentially expressed genes from RNAseq data. Bioinformatics 2009, 26, 136–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, M.; Ball, C.A.; Blake, J.A.; Botstein, D.; Butler, H.; Cherry, J.M.; Davis, A.P.; Dolinski, K.; Dwight, S.S.; Eppig, J.T.; et al. Gene ontology: Tool for the unification of biology. Gene Ontol. Consort. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Wang, L.; Han, Y.; He, Q. clusterProfiler: An R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS J. Integr. Biol. 2012, 16, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, A.; Szklarczyk, D.; Frankild, S.; Kuhn, M.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Lin, J.; Minguez, P.; Bork, P.; von Mering, C.; et al. STRING v9.1: Protein-protein interaction networks, with increased coverage and integration. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, D808–D815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nielsen, J.; Christiansen, J.; Lykke-Andersen, J.; Johnsen, A.H.; Wewer, U.M.; Nielsen, F.C. A family of insulin-like growth factor II mRNA-binding proteins represses translation in late development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 1262–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaniv, K.; Yisraeli, J.K. The involvement of a conserved family of RNA binding proteins in embryonic development and carcinogenesis. Gene 2002, 287, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yisraeli, J.K. VICKZ proteins: A multi-talented family of regulatory RNA-binding proteins. Biol. Cell 2005, 97, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, C.; Dominguez, C.; Allain, F.H. The RNA recognition motif, a plastic RNA-binding platform to regulate post-transcriptional gene expression. FEBS J. 2005, 272, 2118–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowler, E.; Oltean, S. Alternative Splicing in Angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, H.T.; Sorrell, A.M.; Siddle, K. Two isoforms of the mRNA binding protein IGF2BP2 are generated by alternative translational initiation. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e33140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaripour, S.; Esmaeili, H.R.; Gholamhosseini, A.; Rezaei, M.; Sadeghi, S. Assessment of genetic diversity of an endangered tooth-carp, Aphanius farsicus (Teleostei: Cyprinodontiformes: Cyprinodontidae) using microsatellite markers. Mol. Biol. Res. Commun. 2017, 6, 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Relaix, F.; Zammit, P.S. Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration: The cell on the edge returns centre stage. Development 2012, 139, 2845–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cserjesi, P.; Olson, E.N. Myogenin induces the myocyte-specific enhancer binding factor MEF-2 independently of other muscle-specific gene products. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991, 11, 4854–4862. [Google Scholar]

- Megeney, L.A.; Kablar, B.; Garrett, K.; Anderson, J.E.; Rudnicki, M.A. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1173–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Mandel, E.M.; Thomson, J.M.; Wu, Q.; Callis, T.E.; Hammond, S.M.; Conlon, F.L.; Wang, D.Z. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 2006, 38, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Grand, F.; Rudnicki, M.A. Skeletal muscle satellite cells and adult myogenesis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2007, 19, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, R.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yong, W.; Zhao, R.; Pang, W. Lnc-ORA interacts with microRNA-532-3p and IGF2BP2 to inhibit skeletal muscle myogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, K.; Zeng, X.; Zhou, X.; Yan, F.; Yang, S.; Zhao, A. Isolation and identification of goose skeletal muscle satellite cells and preliminary study on the function of C1q and tumor necrosis factor-related protein 3 gene. Anim. Biosci. 2021, 34, 1078–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Primer Purpose | Primer Name | Primer Sequence (5′→3′) | Product Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex test | CHD1-F CHD1-R | TGCAGAAGCAATATTACAAGT AATTCATTATCATCTGGTGG | 466/326 |

| RT-PCR | BP2-F1 BP2-R1 | TGCCTGAAGACTTGTTGCATCC CAAGTTGACAACCTCCTGCTCC | 1246 |

| BP2-F2 BP2-R2 | GCCACCAGCTTGAGAGCTATTCC GGTGCTCTTTGGTTTGCTCCCTG | 1483 | |

| 5′-RACE | GSP-5R NGSP-5R | GAGGAGGGGAGGGTGAGGAGGTCGG GAGAAGAGAGAAGACAAAGTCCCCC | 2292 |

| Genomic DNA cloning and genetic variants identification | BP2-gF1 BP2-gR1 | CCCAAAAGCACCCCACCGCACC GCAAATGACACAGCCAAGAGCC | 1480 |

| BP2-gF2 BP2-gR2 | CATTGCCCTCTCCATGGACCTT CTCCCTCTCGCATCCCCTAACC | 707 | |

| BP2-gF3 BP2-gR3 | AGAGGGCATTTGGGTTTGTCAGT CAAATCCCAAGGGCAAAGAGTGT | 1245 | |

| BP2-gF4 BP2-gR4 | ACACTCTTTGCCCTTGGGATTT AGCCGAGGAAGAGGATGGTTGA | 1358 | |

| BP2-gF5 BP2-gR5 | ATCCTCTTCCTCGGCTGTCCTC AGGGAGAGGGGGAGCAGCAGGG | 836 | |

| BP2-gF6 BP2-gR6 | TTCCCTCCTCGGTGCTTAGATG CGGGCTCCTTTCAACATCTGCT | 1163 | |

| BP2-gF7 BP2-gR7 | TGCCCCGTCGTGGTGTTGGATG TGTCTTCTCCACTTGGCTGCTC | 1643 | |

| BP2-gF8 BP2-gR8 | CGGCCACCCCTTACCACCCATT CTGTTTGGGGTGATGTTTTGGG | 1602 | |

| BP2-gF9 BP2-gR9 | ACCATGGTTTAGCACGTCGGAG TTAGGAATGCCACCCCAAACAG | 848 | |

| BP2-gF10 BP2-gR10 | AGTTCTCGCCAAATCTTCTCCA AGGCAGCCATCAGGAAAAGGGT | 1568 | |

| BP2-gF11 BP2-gR11 | GTTGTGAATATTCCCGCCTGGT AACCCTCTGCCTATGTTAGTC | 923 | |

| qPCR analysis | ACTA2-F ACTA2-R | GGTGTGATGGTTGGTATGGGT TTGTAGAAAGAATGGTGCCAG | 152 |

| BMP2-F BMP2-R | CCAACACCGTGCGCAGCTTCC GTGATGGTAGCTGCTGTTGTT | 191 | |

| IGF1-F IGF1-R | CTGTGTGGTGCTGAGCTGGTT AGTACATCTCCAGCCTCCTCA | 169 | |

| BMP6-F BMP6-R | GGAATTCACGCCTCACCAGCA GGATGTTCATGCAGCACTTGG | 174 | |

| FGF19-F FGF19-R | GCACGGGCAGCTCAGGTATTC TGACTCCACTGGCACCGTGTT | 202 | |

| NODAL-F NODAL-R | GCAACGTCACCCTGGACATCT CTGAGCGTGCCGGTGAGGTTG | 148 | |

| MYPBC3-F MYPBC3-R | GATGTGAGGTGTCTACTAAGG GCACTAAAATTCAACTCTCCA | 196 | |

| ADD2-F ADD2-R | CATCGCCTGCTCGACCTCTAC GCTGGCTGCTGTCACCTCGCT | 132 | |

| β-actin-F β-actin-R | TCCGTGACATCAAGGAGAAG CATGATGGAGTTGAAGGTGG | 224 |

| No | Variations | Region | No | Variations | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | g.240A>G | 5′UTR | 31 | g.8193C>T | Intron 5 |

| 2 | g.531T>C | 5′UTR | 32 | g.8301G>A | Intron 5 |

| 3 | g.1597C>A | 5′UTR | 33 | g.9015–9018del | Intron 6 |

| 4 | g.1973T>C | 5′UTR | 34 | g.9105G>A | Intron 6 |

| 5 | g.2067–2068AG/CA | 5′UTR | 35 | g.9226T>C | Intron 6 |

| 6 | g.2124–2137del | 5′UTR | 36 | g.9769T>A | Intron 6 |

| 7 | g.2299delG | Exon 1 | 37 | g.10383C>T | Intron 8 |

| 8 | g.2304A>C | Exon 1 | 38 | g.10414G>A | Intron 8 |

| 9 | g.2317G>C | Exon 1 | 39 | g.10493G>A | Intron 8 |

| 10 | g.2364C>CTTCT | Exon 1 | 40 | g.10624C>T | Intron 8 |

| 11 | g.3147T>G | Intron 1 | 41 | g.10635C>T | Intron 8 |

| 12 | g.4281A>G | Intron 1 | 42 | g.10695G>A | Exon 9 |

| 13 | g.4487T>C | Intron 1 | 43 | g.10731–10766del | Intron 9 |

| 14 | g.4489G>A | Intron 1 | 44 | g.10780–10786AATGGCA>CTGATGGC | Intron 9 |

| 15 | g.4576G>A | Intron 1 | 45 | g.10818C>T | Intron 9 |

| 16 | g.4600G>C | Intron 1 | 46 | g.10820G>A | Intron 9 |

| 17 | g.4605G>A | Intron 1 | 47 | g.10824C>T | Intron 9 |

| 18 | g.4621A>G | Intron 1 | 48 | g.10848T>C | Intron 9 |

| 19 | g.5102G>A | Intron 1 | 49 | g.10861T>C | Intron 9 |

| 20 | g.6109T>C | Intron 1 | 50 | g.10869A>G | Intron 9 |

| 21 | g.6980C>T | Intron 3 | 51 | g.10875–10876TT>CC | Intron 9 |

| 22 | g.7824G>A | Intron 5 | 52 | g.10927G>A | Exon 10 |

| 23 | g.7898G>A | Intron 5 | 53 | g.11292T>C | Intron 11 |

| 24 | g.7951A>G | Intron 5 | 54 | g.11301T>C | Intron 11 |

| 25 | g.8005A>G | Intron 5 | 55 | g.11318C>T | Intron 11 |

| 26 | g.8116A>G | Intron 5 | 56 | g.11067C>T | Intron 11 |

| 27 | g.8121delC | Intron 5 | 57 | g.11868T>G | Intron 11 |

| 28 | g.8127T>C | Intron 5 | 58 | g.11705C>A | Intron 11 |

| 29 | g.8138T>C | Intron 5 | 59 | g.11723C>A | Intron 9 |

| 30 | g.8154G>A | Intron 5 | 60 | g.12082G>C | 3′UTR |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, C.; Liu, Y.; Dai, J.; Chen, S.; He, D. Molecular Characterization and Functional Insights into Goose IGF2BP2 During Skeletal Muscle Development. Animals 2026, 16, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010058

Wang C, Liu Y, Dai J, Chen S, He D. Molecular Characterization and Functional Insights into Goose IGF2BP2 During Skeletal Muscle Development. Animals. 2026; 16(1):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010058

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Cui, Yi Liu, Jiuli Dai, Shufang Chen, and Daqian He. 2026. "Molecular Characterization and Functional Insights into Goose IGF2BP2 During Skeletal Muscle Development" Animals 16, no. 1: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010058

APA StyleWang, C., Liu, Y., Dai, J., Chen, S., & He, D. (2026). Molecular Characterization and Functional Insights into Goose IGF2BP2 During Skeletal Muscle Development. Animals, 16(1), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010058