The Wrong Assumptions of the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Turtle Nests with Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Mechanisms of Heat Transfer in Soil

2.1. Factors Influencing Soil Beach Heat Transfer

2.1.1. Soil Properties

2.1.2. Environmental Conditions

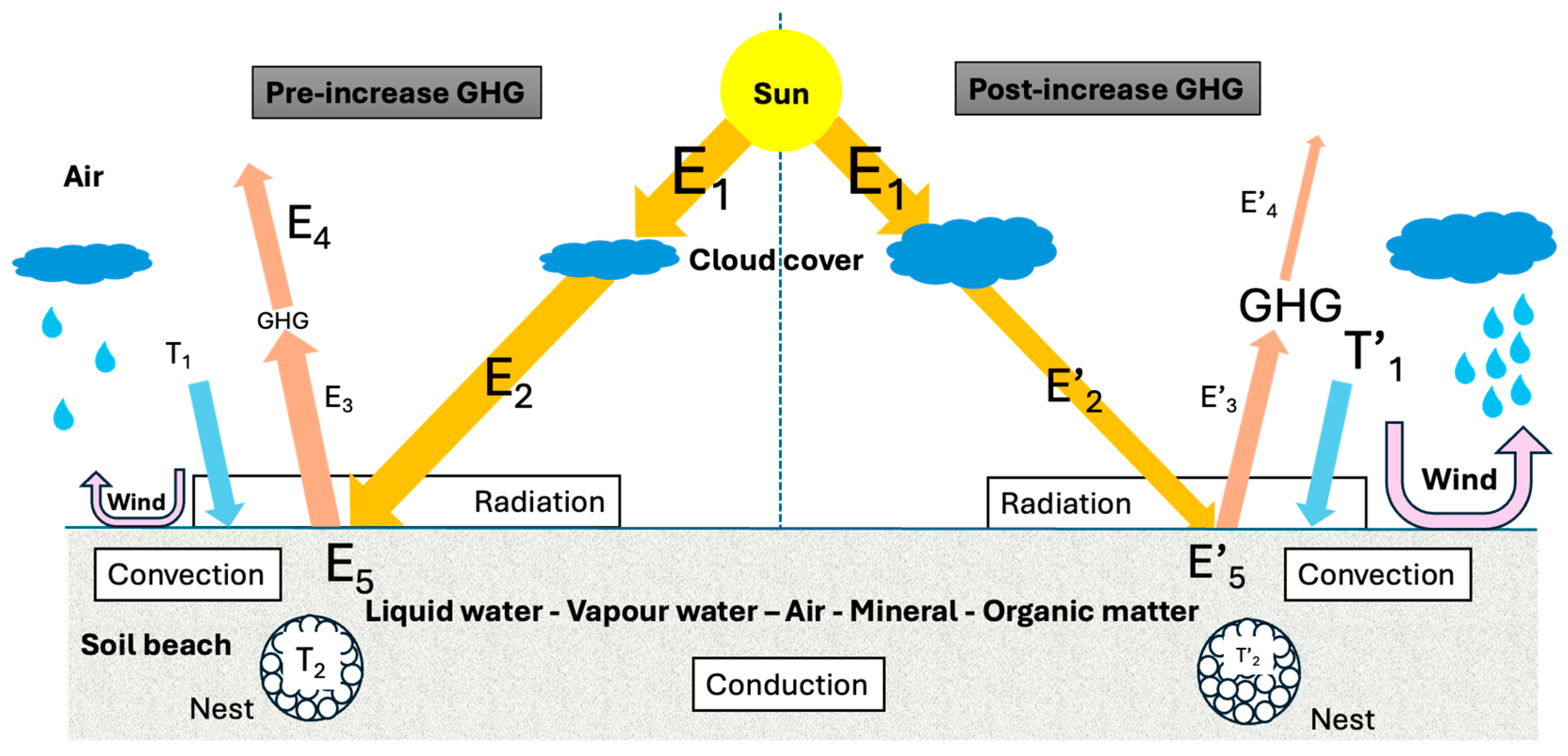

3. Interplay of Factors Changing Beach Soil Temperature

4. Discussion

5. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CTE | Constant Temperature Equivalent |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| TSD | Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination |

| TRT | Transitional Range of Temperatures |

| TSP | Thermosensitive Period of development for sex determination |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 35–115. [Google Scholar]

- Bull, J.J. Sex determination in reptiles. Q. Rev. Biol. 1980, 55, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girondot, M.; Monsinjon, J.; Guillon, J.-M. Delimitation of the embryonic thermosensitive period for sex determination using an embryo growth model reveals a potential bias for sex ratio prediction in turtles. J. Therm. Biol. 2018, 73, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mrosovsky, N.; Pieau, C. Transitional range of temperature, pivotal temperatures and thermosensitive stages for sex determination in reptiles. Amphibia-Reptilia 1991, 12, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, C.J.; Girondot, M.; Janzen, F.J. The tortoise and the air: Climate shapes sex-ratio reaction norm variation in turtles. Evolution 2025, 79, qpaf126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girondot, M.; Carvajal, G.A.; Scott, K. Estimating hatchling sex ratios. In Research and Management Techniques for the Conservation of Sea Turtles; Phillott, A., Rees, A.F., Fuentes, M.M.P.B., Eds.; IUCN SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group: Gland, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Monsinjon, J.; Guillon, J.-M.; Wyneken, J.; Girondot, M. Thermal reaction norm for sexualization: The missing link between temperature and sex ratio for temperature-dependent sex determination. Ecol. Model. 2022, 473, 110119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.M.P.B.; Monsinjon, J.; Lopez, M.; Lara, P.; Santos, A.; dei Marcovaldi, M.A.G.; Girondot, M. Sex ratio estimates for species with temperature-dependent sex determination differ according to the proxy used. Ecol. Model. 2017, 365, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davenport, J. Sea turtles and the greenhouse effect. Br. Herpetol. Soc. Bull. 1989, 29, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Davenport, J. Temperature and the life-history strategies of sea turtles. J. Therm. Biol. 1997, 22, 479–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrosovsky, N. Sex ratios of sea turtles. J. Exp. Zool 1994, 270, 16–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janzen, F.J. Climate change and temperature-dependent sex determination in reptiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1994, 91, 7487–7490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santidrián Tomillo, P.; Genovart, M.; Paladino, F.V.; Spotila, J.R.; Oro, D. Climate change overruns resilience conferred by temperature-dependent sex determination in sea turtles and threatens their survival. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 2980–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, G.C.; Broderick, A.C.; Glen, F.; Godley, B.J. Climate change and sea turtles: A 150-year reconstruction of incubation temperatures at a major marine turtle rookery. Glob. Change Biol. 2003, 9, 642–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloë, J.-O.; Cozens, J.; Renom, B.; Taxonera, A.; Hays, G.C. Effects of rising temperature on the viability of an important sea turtle rookery. Nat. Clim. Change 2014, 4, 513–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloë, J.-O.; Esteban, N.; Berkel, J.; Hays, G.C. Sand temperatures for nesting sea turtles in the Caribbean: Implications for hatchling sex ratios in the face of climate change. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2016, 474, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laloë, J.-O.; Cozens, J.; Renom, B.; Taxonera, A.; Hays, G.C. Climate change and temperature-linked hatchling mortality at a globally important sea turtle nesting site. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4922–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esteban, N.; Laloë, J.O.; Mortimer, J.A.; Guzman, A.N.; Hays, G.C. Male hatchling production in sea turtles from one of the world’s largest marine protected areas, the Chagos Archipelago. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, A.R.; Marques, A.; Barbosa, C.; Broderick, A.C.; Godley, B.J.; Hawkes, L.A.; Rebelo, R.; Regalla, A.; Catry, P. Balanced primary sex ratios and resilience to climate change in a major sea turtle population. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2017, 577, 189–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, A.R.; Varela, M.R.; Barbosa, C.; Broderick, A.C.; Catry, P.; Hawkes, L.A.; Regalla, A.; Godley, B.J. Climate change resilience of a globally important sea turtle nesting population. Glob. Change Biol. 2019, 25, 522–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, M.M.P.B.; Maynard, J.A.; Guinea, M.; Bell, I.P.; Werdell, P.J.; Hamann, M. Proxy indicators of sand temperature help project impacts of global warming on sea turtles in northern Australia. Endanger. Species Res. 2009, 9, 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girondot, M.; Kaska, Y. Nest temperatures in a loggerhead-nesting beach in Turkey is more determined by sea surface temperature than air temperature. J. Therm. Biol. 2015, 47, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, B.P.; Kearney, M.R.; Whiting, S.D.; Mitchell, N.J. Microclimate modelling of beach sand temperatures reveals high spatial and temporal variation at sea turtle rookeries. J. Therm. Biol. 2020, 88, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrício, A.R.; Hawkes, L.A.; Monsinjon, J.R.; Godley, B.J.; Fuentes, M. Climate change and marine turtles: Recent advances and future directions. Endanger. Species Res. 2021, 44, 363–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S). ERA5: Fifth Generation of ECMWF Atmospheric Reanalyses of the Global Climate; C3S: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, G.S.; Norman, J.M. Heat flow in the soil. In An Introduction to Environmental Biophysics; Campbell, G.S., Norman, J.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Bristow, R.L.; Campbell, G.S. On the relationship between incoming solar radiation and daily maximum and minimum temperature. Agric. For. Meteorol. 1984, 31, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, I.; Siddiqui, O. Heat transfer aspects of energy. Compr. Energy Syst. 2018, 1, 422–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluft, L.; Stevens, B.; Brath, M.; Buehler, S.A. A conceptual framework for understanding longwave cloud effects on climate sensitivity. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2025, 25, 9075–9084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, M.R.; Porter, W.P. NicheMapR—An R package for biophysical modelling: The microclimate model. Ecography 2017, 40, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammon, M.; Fossette, S.; Karrech, A.; McGrath, G.; Alkhatib, S.; Mitchell, N.J. An application of finite element analysis predicts unique temperatures and fates for flatback sea turtle embryos. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, 250238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M.P.; Allen, C.D.; Eguchi, T.; Bell, I.P.; LaCasella, E.L.; Hilton, W.A.; Hof, C.A.M.; Dutton, P.H. Environmental warming and feminization of one of the largest sea turtle populations in the world. Curr. Biol. 2018, 28, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uçar, A.H.; Kaska, Y.; Ergene, S.; Aymak, C.; Kaçar, Y.; Kaska, A.; İli, P. Sex ratio estimation of the most eastern main loggerhead sea turtle nesting site: Anamur beach, Mersin, Turkey. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2012, 58, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarı, F.; Kaska, Y. Loggerhead sea turtle hatchling sex ratio differences between two nesting beaches in Turkey. Isr. J. Ecol. Evol. 2015, 61, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, P.; Lazar, B.; Pont, S.; Tomas, J.; Zizzo, N.; Alegre, F.; Badillo, J.; Di Summa, A.; Freggi, D.; Lackovic, G.; et al. Sex ratios of juvenile loggerhead sea turtles Caretta caretta in the Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2006, 324, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casale, P.; Freggi, D.; Maffucci, F.; Hochscheid, S. Adult sex ratios of loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in two Mediterranean foraging grounds. Sci. Mar. 2014, 78, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocci, P.; Bracchetti, L.; Angelini, V.; Bucchia, M.; Pari, S.; Mosconi, G.; Palermo, F.A. Development and pre-validation of a testosterone enzyme immunoassay (EIA) for predicting the sex ratio of immature loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) recovered along the western coast of the central Adriatic Sea. Mar. Biol. 2014, 161, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.; Boura, L.; Venizelos, L. Population structure for sea turtles at drini bay: An important nearshore foraging and developmental habitat in Albania. Chelonian Conserv. Biol. 2013, 12, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, A.F.; Margaritoulis, D.; Newman, R.; Riggall, T.E.; Tsaros, P.; Zbinden, J.A.; Godley, B.J. Ecology of loggerhead marine turtles Caretta caretta in a neritic foraging habitat: Movements, sex ratios and growth rates. Mar. Biol. 2013, 160, 519–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, A.F.; Alfaro-Shigueto, J.; Barata, P.C.R.; Bjorndal, K.A.; Bolten, A.B.; Bourjea, J.; Broderick, A.C.; Campbell, L.M.; Cardona, L.; Carreras, C.; et al. Review: Are we working towards global research priorities for management and conservation of sea turtles? Endanger. Species Res. 2016, 31, 337–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Girondot, M. The Wrong Assumptions of the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Turtle Nests with Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination. Animals 2026, 16, 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010097

Girondot M. The Wrong Assumptions of the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Turtle Nests with Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination. Animals. 2026; 16(1):97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010097

Chicago/Turabian StyleGirondot, Marc. 2026. "The Wrong Assumptions of the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Turtle Nests with Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination" Animals 16, no. 1: 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010097

APA StyleGirondot, M. (2026). The Wrong Assumptions of the Effects of Climate Change on Marine Turtle Nests with Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination. Animals, 16(1), 97. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010097