Effect of Preweaning Socialization on Postweaning Biomarkers of Stress, Inflammation, Immunity and Metabolism in Saliva and Serum of Iberian Piglets

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

2.2. Data and Sample Collection

2.2.1. Saliva Sampling

2.2.2. Blood Samples

2.2.3. Growth Measurements

2.3. Biomarker Analyses

2.3.1. Salivary Biomarker Analyses

2.3.2. Serum Biomarker Analyses

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Salivary Biomarkers

3.2. Serum Biomarker Results

3.2.1. Stress and Inflammation Biomarkers

3.2.2. Metabolic Biomarkers

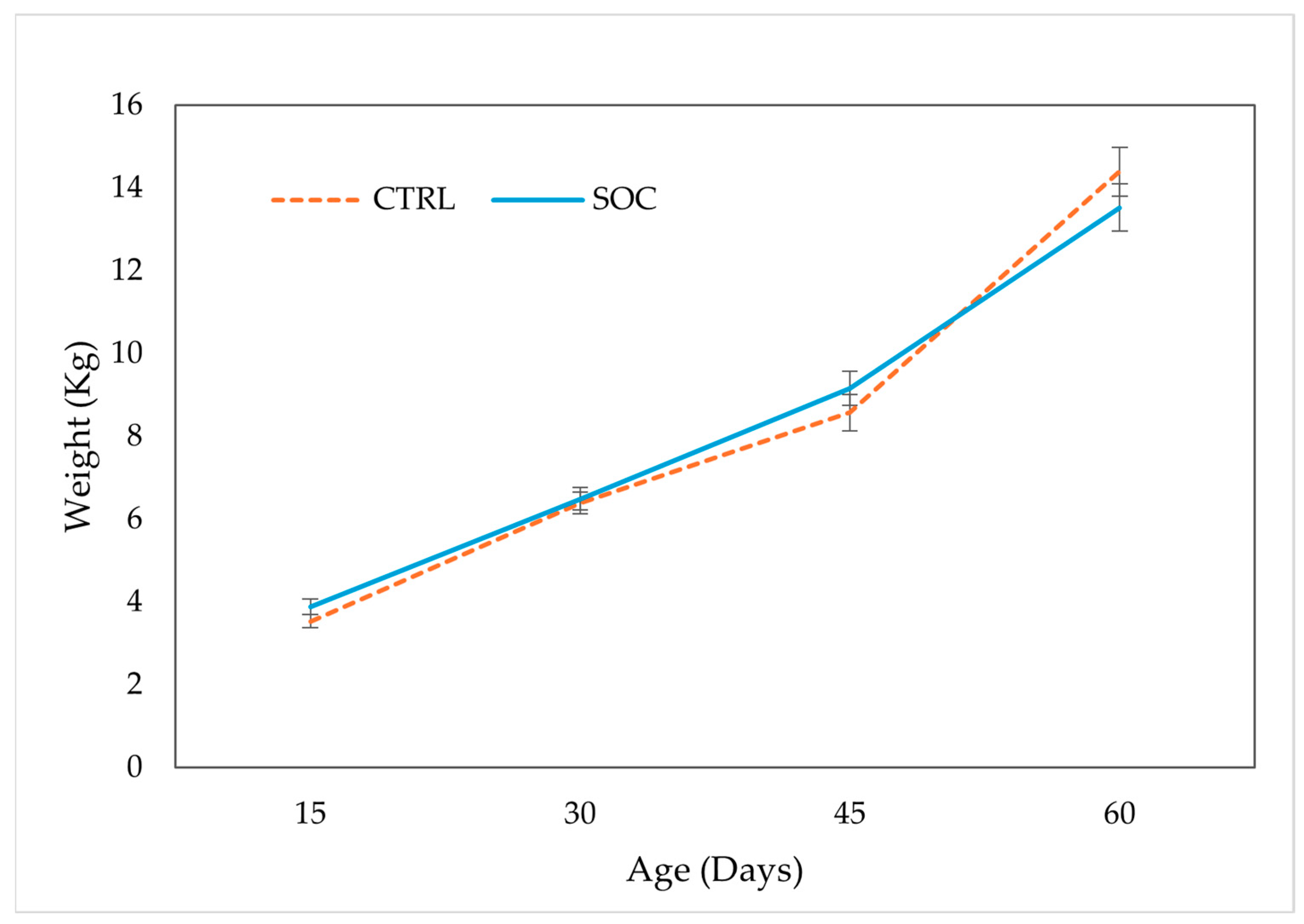

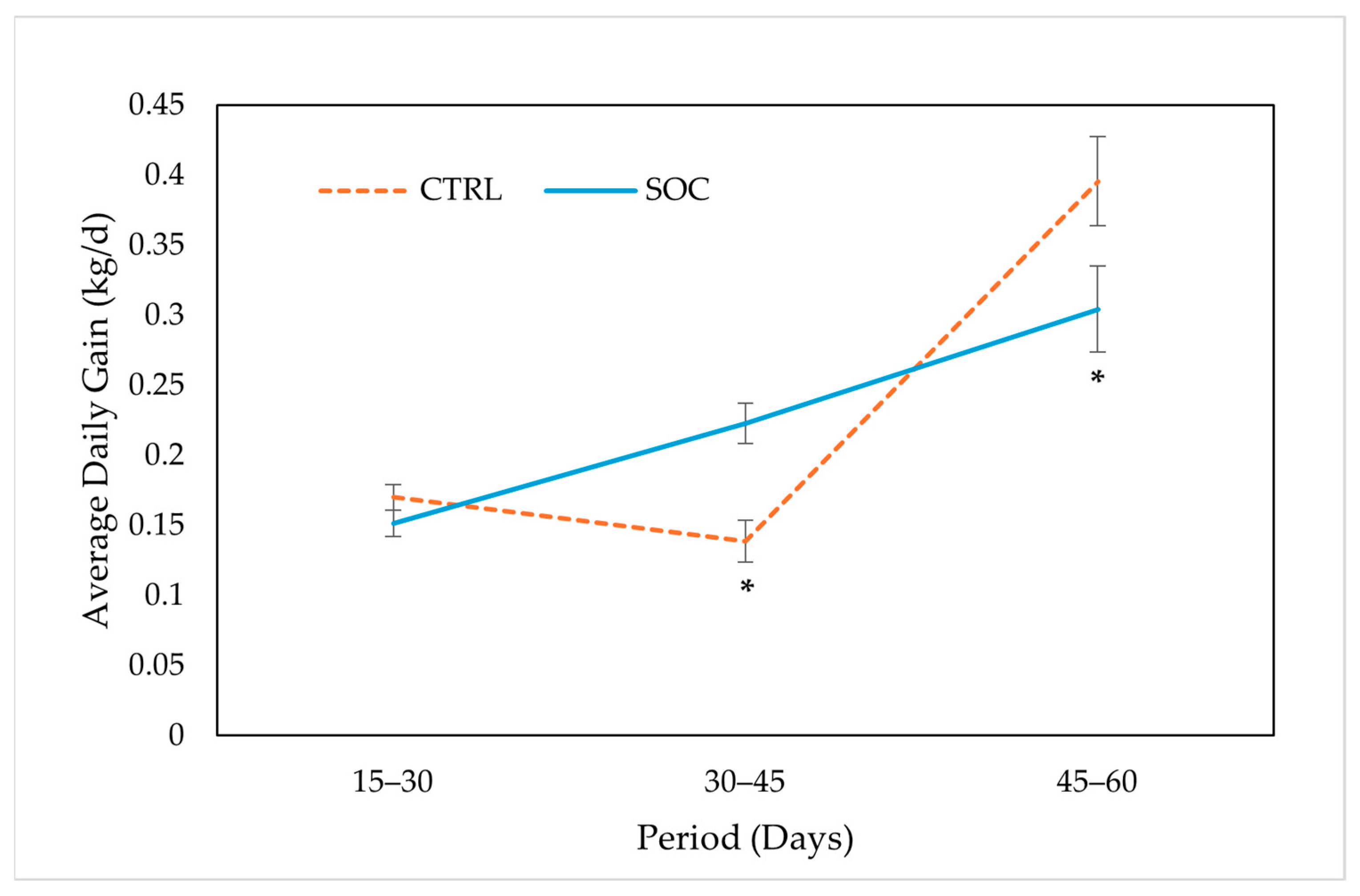

3.3. Growth Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Stress-Related Biomarkers

4.2. Inflammatory and Immune Markers

4.3. Metabolic Parameters

4.4. Growth Performance

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADA | Adenosine Deaminase |

| ADG | Average Daily Gain |

| BChE | Butyryl-cholinesterase |

| BW | Body Weight |

| BUN | Blood Urea Nitrogen |

| CgA | Chromogranin A |

| Cort | Cortisol |

| Crts | Cortisone |

| CRP | C-Reactive Protein |

| CTRL | Control group |

| D30 | Day 30 of age |

| D45 | Day 45 of age |

| D60 | Day 60 of age |

| F | Female |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

| HDL | High Density Lipoprotein |

| Hp | Haptoglobin |

| HPA | Hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| LD0 | Lactation day 0 (birth) |

| LD15 | Lactation day 15 |

| LD30 | Weaning |

| LDL | Low Density Lipoprotein |

| M | Male |

| n | Number of observations (litters/animals) per group |

| OT | Oxytocin |

| PON-1 | Paraoxonase 1 |

| pwD0 | Weaning |

| pwD7 | Post-weaning day 7 |

| pwD15 | Post-weaning day 15 |

| pwD30 | Post-weaning day 30 |

| sAA | Salivary Alpha-Amylase |

| SAM | Sympatho-adreno-medullary |

| SOC | Socialization group |

| TEA | Total Esterase Activity |

| ZnO | Zinc Oxide |

References

- Campbell, J.M.; Crenshaw, J.D.; Polo, J. The biological stress of early weaned piglets. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2013, 4, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minton, J.E. Function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic nervous system in models of acute stress in domestic farm animals. J. Anim. Sci. 1994, 72, 1891–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colson, V.; Martin, E.; Orgeur, P.; Prunier, A. Influence of Housing and Social Changes on Growth, Behaviour and Cortisol in Piglets at Weaning. Physiol. Behav. 2012, 107, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Kerschaver, C.; Vandaele, M.; Van Tichelen, K.; Van De Putte, T.; Fremaut, D.; Van Ginneken, C.; Michiels, J.; Degroote, J. Effect of co-mingling non-littermates during lactation and feed familiarity at weaning on the performance, skin lesions and health of piglets. Livest. Sci. 2023, 259, 104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, L.C.; Ko, H.-L.; Yang, C.-H.; Llonch, L.; Manteca, X.; Camerlink, I.; Llonch, P. Early socialisation as a strategy to increase piglets’ social skills in intensive farming conditions. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2018, 206, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto, R.; García-Casco, J.; Lara, L.; Palma-Granados, P.; Izquierdo, M.; Hernandez, F.; Batorek-Lukač, N. Ibérico (Iberian) pig. In European Local Pig Breeds—Diversity and Performance. A Study of Project TREASURE; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ibérico General—Ganado Porcino. Available online: https://rfeagas.es/razas/porcino/iberico-general/ (accessed on 13 August 2025).

- Ji, W.; Bi, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Liu, R.; Zhang, X.; Shu, Y.; Li, X.; Bao, J.; Liu, H. Impact of early socialization environment on social behavior, physiology and growth performance of weaned piglets. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2021, 238, 105314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Toribio, J.-A. Does pre-weaning socialisation with non-littermates reduce piglet’s weaning stress when regrouped with unfamiliar piglets post-weaning? Vet. Evid. 2023, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, J.; Matas, M.; Ibáñez-López, F.J.; Lázaro-Carrasco Hernández, I.; Sotillo, J.; Gutierrez, A.M. The Connection Between Stress and Immune Status in Pigs: A First Salivary Analytical Panel for Disease Differentiation. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 881435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerón, J.J.; Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Escribano, D.; Martínez-Miró, S.; López-Martínez, M.J.; Ortín-Bustillo, A.; Franco-Martínez, L.; Rubio, C.P.; Muñoz-Prieto, A.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; et al. Basics for the potential use of saliva to evaluate stress, inflammation, immune system, and redox homeostasis in pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2022, 18, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pomorska-Mól, M.; Markowska-Daniel, I.; Kwit, K.; Wierzchosławski, K. Major acute phase proteins in pig serum from birth to slaughter. J. Vet. Res. 2012, 56, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruis, M.A.W.; Te Brake, J.H.A.; Engel, B.; Ekkel, E.D.; Buist, W.G.; Blokhuis, H.J.; Koolhaas, J.M. The Circadian Rhythm of Salivary Cortisol in Growing Pigs: Effects of Age, Gender, and Stress. Physiol. Behav. 1997, 62, 623–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Botía, M.; Llamas-Amor, E.; Cerón, J.J.; Ramis-Vidal, G.; López-Juan, A.L.; Benedé, J.L.; Escribano, D.; Martínez-Subiela, S.; López-Arjona, M. Cortisone in saliva of pigs: Validation of a new assay and changes after thermal stress. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tecles, F.; Cerón, J.J. Determination of whole blood cholinesterase in different animal species using specific substrates. Res. Vet. Sci. 2001, 70, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blavi, L.; Solà-Oriol, D.; Llonch, P.; López-Vergé, S.; Martín-Orúe, S.M.; Pérez, J.F. Management and feeding strategies in early life to increase piglet performance and welfare around weaning: A review. Animals 2021, 11, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moscovice, L.R.; Gimsa, U.; Otten, W.; Eggert, A. Salivary cortisol, but not oxytocin, varies with social challenges in domestic pigs: Implications for measuring emotions. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 899397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, K.; Rauh, A.; Harlizius, J.; Weiß, C.; Scholz, T.; Schulze-Horsel, T.; Escribano, D.; Ritzmann, M.; Zöls, S. Pain and distress responses of suckling piglets to injection and castration under local anaesthesia with procaine and lidocaine—Part 1: Cortisol, chromogranin A, wound healing, weights, losses. Tierärztliche Prax. Ausg. G Großtiere/Nutztiere 2019, 47, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rault, J.L.; van den Munkhof, M.; Buisman-Pijlman, F.T.A. Oxytocin as an indicator of psychological and social well-being in domesticated animals: A critical review. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valros, A.; Lopez-Martinez, M.J.; Munsterhjelm, C.; Lopez-Arjona, M.; Cerón, J.J. Novel saliva biomarkers for stress and infection in pigs: Changes in oxytocin and procalcitonin in pigs with tail-biting lesions. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022, 153, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarpia, L.; Grandone, I.; Contaldo, F.; Pasanisi, F. Butyrylcholinesterase as a prognostic marker: A review of the literature. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2013, 4, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Aguilar, M.; Escribano, D.; Martinez-Miro, S.; Lopez-Arjona, L.; Rubio, C.; Martinez-Subiela, S.; Ceron, J.J.; Tecles, F. Application of a score for evaluation of pain, distress and discomfort in pigs with lameness and prolapses: Correlation with saliva biomarkers and severity of the disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019, 126, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Oohashi, T.; Sato, K.; Oikawa, S. Bovine paraoxonase 1 activities in serum and distribution in lipoproteins. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2005, 67, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-Aguilar, M.D.; Tvarijonaviciute, A.; Monkeviciene, I.; Martín-Cuervo, M.; González-Arostegui, L.G.; Franco-Martínez, L.; Cerón, J.J.; Tecles, F.; Escribano, D. Characterization of total adenosine deaminase activity (ADA) and its isoenzymes in saliva and serum in health and inflammatory conditions in four different species: An analytical and clinical validation pilot study. BMC Vet. Res. 2020, 16, 384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piñeiro, C.; Piñeiro, M.; Morales, J.; Carpintero, R.; Campbell, F.M.; Eckersall, P.D.; Toussaint, M.J.M.; Alava, M.A.; Lampreave, F. Pig acute-phase protein levels after stress induced by changes in the pattern of food administration. Animal 2007, 1, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanitz, E.; Tuchscherer, M.; Puppe, B.; Tuchscherer, A.; Stabenow, B. Consequences of repeated early isolation in domestic piglets (Sus scrofa) on their behavioural, neuroendocrine, and immunological responses. Brain Behav. Immun. 2004, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Tang, H.; Ren, P.; Kong, X.; Wu, G.; Yin, Y.; Wang, Y. Dietary Supplementation with l-Arginine Partially Counteracts Serum Metabonome Induced by Weaning Stress in Piglets. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 5214–5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wen, Z.; Jiang, X.; Ma, X.; Han, X. Weaning Stress Perturbs Gut Microbiome and Its Metabolic Profile in Piglets. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarratt, L.; James, S.E.; Kirkwood, R.N.; Nowland, T.L. Effects of Caffeine and Glucose Supplementation at Birth on Piglet Pre-Weaning Growth, Thermoregulation, and Survival. Animals 2023, 13, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, D.; Shen, C.; Luo, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Xu, J. Remodeling of Hepatic Glucose Metabolism in Response to Early Weaning in Piglets. Animals 2024, 14, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, D.H.; Xiong, X.; Yang, H.S.; Wang, M.W.; He, Y.J.; Liu, Y.H.; Yin, Y.L. Effect of dietary soy oil, glucose, and glutamine on growth performance, amino acid profile, blood profile, immunity, and antioxidant capacity in weaned piglets. Sci. China Life Sci. 2018, 61, 1233–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Wu, C.C.; Feng, J. Effect of dietary antibacterial peptide and zinc-methionine on performance and serum biochemical parameters in piglets. Czech J. Anim. Sci. 2011, 56, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, J.M.; Kim, J.C.; Hansen, C.F.; Mullan, B.P.; Hampson, D.J.; Pluske, J.R. Effects of feeding low protein diets to piglets on plasma urea nitrogen, faecal ammonia nitrogen, the incidence of diarrhoea and performance after weaning. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2008, 62, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Floc’h, N.; Furbeyre, H.; Prunier, A.; Louveau, I. Effect of Surgical or Immune Castration on Postprandial Nutrient Profiles in Male Pigs. Arch. Anim. Nutr. 2019, 73, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colson, V.; Orgeur, P.; Foury, A.; Mormède, P. Consequences of weaning piglets at 21 and 28 days on growth, behaviour and hormonal responses. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2006, 98, 70–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanaan, V.T.; Pajor, E.A.; Lay, D.C.; Richert, B.T.; Garner, J.P. A note on the effects of co-mingling piglet litters on pre-weaning growth, injuries and responses to behavioural tests. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2008, 110, 386–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients | Content | Nutrient Levels | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Barley | 21.00 | Crude protein | 16.99 |

| Wheat | 16.00 | Crude fat | 4.76 |

| Corn | 13.50 | Crude fiber | 4.14 |

| Soybean meal | 11.80 | Lysine | 1.25 |

| Yeast products | 8.00 | Methionine | 0.50 |

| Soybean concentrate | 7.00 | Sodium | 0.32 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 6.50 | Calcium | 0.40 |

| Corn flakes | 3.00 | Phosphorus | 0.50 |

| Barley flakes | 2.50 | Crude ashes | 4.25 |

| Sodium chloride | 1.30 | ||

| Calcium carbonate | 1.10 | ||

| Sodium salts | 1.00 | ||

| Dehydrated seaweed (Chlorella vulgaris) | 0.90 | ||

| Aspergillus by-products | 0.85 | ||

| Vegetable protein | 0.80 | ||

| Sweet whey | 0.75 | ||

| Re-fatted whey | 0.70 | ||

| Beet pulp | 0.60 | ||

| Soybean oil | 0.58 | ||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 0.53 | ||

| L-Lysine | 0.37 | ||

| DL-Methionine | 0.18 | ||

| L-Threonine | 0.22 | ||

| L-Tryptophan | 0.07 | ||

| L-Valine | 0.09 | ||

| Vitamin-Mineral premix 1 | 0.50 | ||

| Preservatives (E237) | 0.16 |

| Saliva Biomarkers at Weaning and on Day 7 Post-Weaning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Group | Sex | p Value | |||

| CTRL | SOC | F | M | Group | Sex | |

| At weaning | ||||||

| Cortisol D0 (µg/dL) | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | 0.29 ± 0.04 | 0.23 ± 0.04 | 0.961 | 0.263 |

| Cortisone D0 (ng/mL) | 2.88 ± 0.37 | 2.80 ± 0.36 | 2.93 ± 0.38 | 2.75 ± 0.35 | 0.879 | 0.725 |

| Oxytocin D0 (pg/mL) | 5845.15 ± 459.01 † | 4688.75 ± 445.31 † | 5404.36 ± 470.72 | 5129.53 ± 436.17 | 0.080 | 0.674 |

| CgA D0 (ng/mL) | 641.51 ± 77.89 | 692.21 ± 75.57 | 663.83 ± 79.88 | 669.88 ± 74.02 | 0.645 | 0.956 |

| sAA D0 (U/L) | 6688.66 ± 2183.37 | 8566.50 ± 2118.20 | 8481.67 ± 2239.08 | 6773.50 ± 2074.74 | 0.543 | 0.582 |

| ADA D0 (U/L) | 5723.08 ± 674.42 a | 2522.03 ± 654.29 b | 4437.46 ± 691.63 | 3807.66 ± 640.87 | 0.002 | 0.512 |

| Day 7 post-weaning | ||||||

| Cortisol D7 (µg/dL) | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.12 ± 0.04 | 0.13 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.661 | 0.469 |

| Cortisone D7 (ng/mL) | 2.93 ± 0.44 | 1.88 ± 0.44 | 2.12 ± 0.47 | 2.69 ± 0.43 | 0.102 | 0.381 |

| Oxytocin D7 (pg/mL) | 4974.40 ± 475.04 † | 6125.50 ± 472.98 † | 5435.60 ± 501.11 | 5664.31 ± 457.11 | 0.094 | 0.741 |

| CgA D7 (ng/mL) | 787.80 ± 69.64 a | 518.38 ± 69.34 b | 732.79 ± 73.47 | 573.38 ± 67.01 | 0.009 | 0.122 |

| sAA D7 (U/L) | 7900.96 ± 1531.57 | 5774.75 ± 1524.92 | 6313.43 ± 1615.63 | 7362.28 ± 1473.75 | 0.332 | 0.639 |

| ADA D7 (U/L) | 5478.00 ± 672.74 † | 3789.83 ± 669.82 † | 4928.38 ± 709.66 | 4339.45 ± 647.34 | 0.084 | 0.549 |

| Serum Parameters on Day 7 Post-Weaning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Group | Sex | p Value | |||

| CTRL | SOC | F | M | Group | Sex | |

| BChE (µmol mL/minute) | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.46 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.01 a | 0.50 ± 0.01 b | 0.311 | <0.0001 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 56.91 ± 5.91 | 51.70 ± 5.88 | 56.19 ± 6.23 | 52.42 ± 5.68 | 0.537 | 0.662 |

| Haptoglobin (g/L) | 1.54 ± 0.14 a | 1.12 ± 0.14 b | 1.48 ± 0.15 | 1.18 ± 0.13 | 0.036 | 0.132 |

| PON-1 (U/L) | 47.99 ± 2.58 | 51.21 ± 2.57 | 49.14 ± 2.73 | 50.06 ± 2.49 | 0.383 | 0.807 |

| Immunoglobulin G (mg/L) | 4.69 ± 0.27 | 4.37 ± 0.27 | 4.54 ± 0.29 | 4.53 ± 0.26 | 0.405 | 0.972 |

| Serum Parameters on Day 7 Post-Weaning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Group | Sex | p Value | |||

| CTRL | SOC | F | M | Group | Sex | |

| HDL * (mg/dL) | 32.56 ± 1.60 a | 45.71 ± 1.54 b | 41.26 ± 1.66 † | 37.02 ± 1.48 † | <0.0001 | 0.064 |

| LDL * (mg/dL) | 25.67 ± 1.70 a | 37.26 ± 1.64 b | 31.59 ± 1.77 | 31.34 ± 1.57 | <0.0001 | 0.918 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 76.33 ± 3.76 a | 102.77 ± 3.62 b | 92.69 ± 3.90 | 86.41 ± 3.47 | <0.0001 | 0.236 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 52.40 ± 3.72 | 49.72 ± 3.58 | 53.79 ± 3.85 | 48.34 ± 3.43 | 0.606 | 0.297 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.46 ± 0.02 | 0.45 ± 0.01 | 0.47 ± 0.02 † | 0.43 ± 0.01 † | 0.607 | 0.057 |

| Urea (mg/dL) | 19.10 ± 1.04 a | 12.06 ± 1.00 b | 18.90 ± 1.08 a | 12.26 ± 0.96 b | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Total Proteins (g/L) | 55.13 ± 0.66 | 54.51 ± 0.63 | 55.34 ± 0.68 | 54.30 ± 0.61 | 0.505 | 0.264 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 101.85 ± 2.91 a | 119.13 ± 2.81 b | 108.52 ± 3.02 | 112.47 ± 2.69 | 0.0001 | 0.335 |

| Lactate (mg/dL) | 64.00 ± 3.41 | 57.92 ± 3.28 | 61.57 ± 3.54 | 60.35 ± 3.15 | 0.206 | 0.798 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Becerra, C.; Hernández-García, F.I.; Gómez-Quintana, A.; Cerón, J.J.; Botía, M.; Mateos, C.; Izquierdo, M. Effect of Preweaning Socialization on Postweaning Biomarkers of Stress, Inflammation, Immunity and Metabolism in Saliva and Serum of Iberian Piglets. Animals 2026, 16, 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010088

Becerra C, Hernández-García FI, Gómez-Quintana A, Cerón JJ, Botía M, Mateos C, Izquierdo M. Effect of Preweaning Socialization on Postweaning Biomarkers of Stress, Inflammation, Immunity and Metabolism in Saliva and Serum of Iberian Piglets. Animals. 2026; 16(1):88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010088

Chicago/Turabian StyleBecerra, Carolina, Francisco Ignacio Hernández-García, Antonia Gómez-Quintana, José Joaquín Cerón, María Botía, Clara Mateos, and Mercedes Izquierdo. 2026. "Effect of Preweaning Socialization on Postweaning Biomarkers of Stress, Inflammation, Immunity and Metabolism in Saliva and Serum of Iberian Piglets" Animals 16, no. 1: 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010088

APA StyleBecerra, C., Hernández-García, F. I., Gómez-Quintana, A., Cerón, J. J., Botía, M., Mateos, C., & Izquierdo, M. (2026). Effect of Preweaning Socialization on Postweaning Biomarkers of Stress, Inflammation, Immunity and Metabolism in Saliva and Serum of Iberian Piglets. Animals, 16(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010088