Gouldian Finches (Chloebia gouldiae) Increase the Frequency of Head Movements with Increasing Risk at Water-holes but Prolong Interscan Intervals While Drinking: Two Different Strategies?

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Location

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

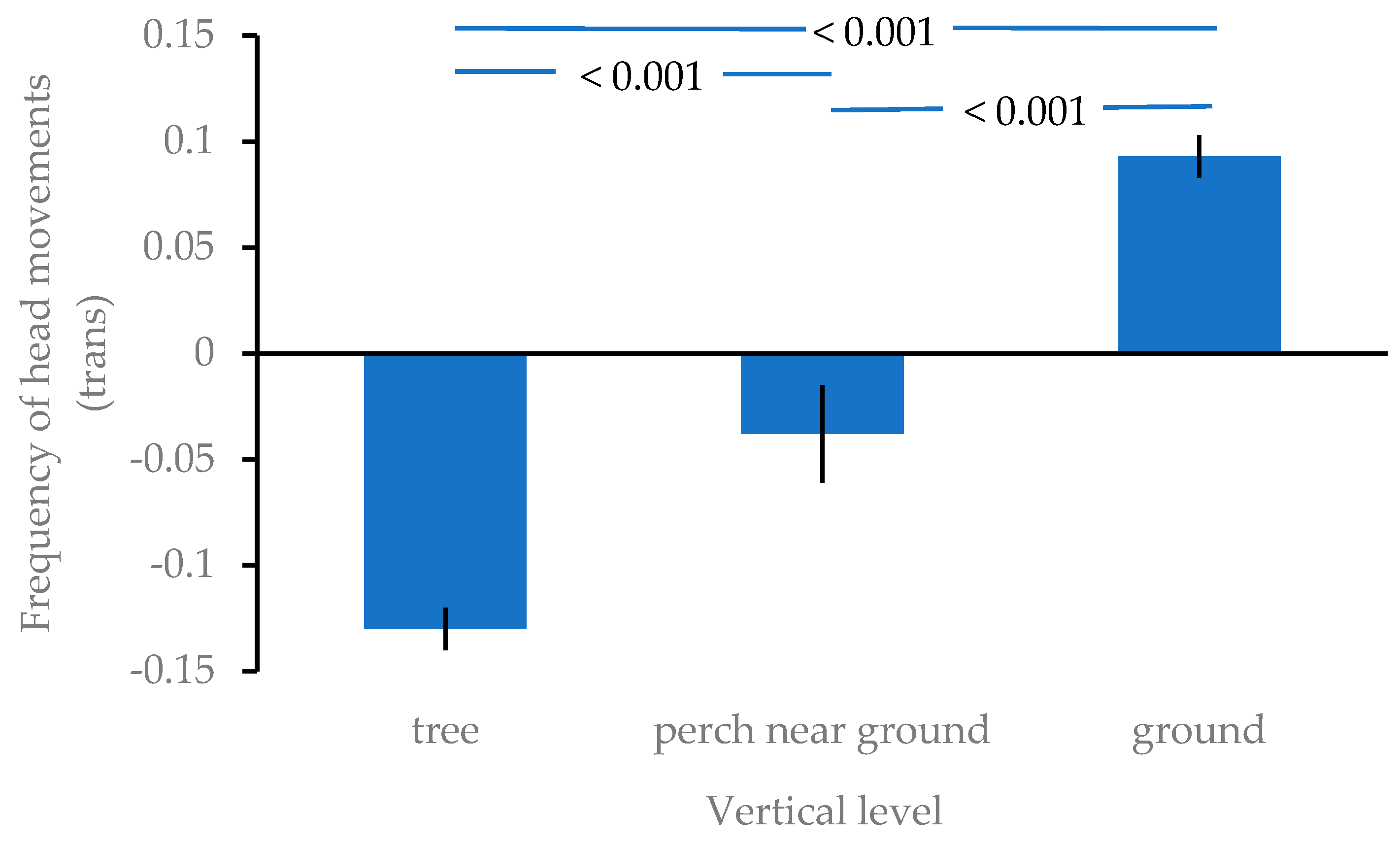

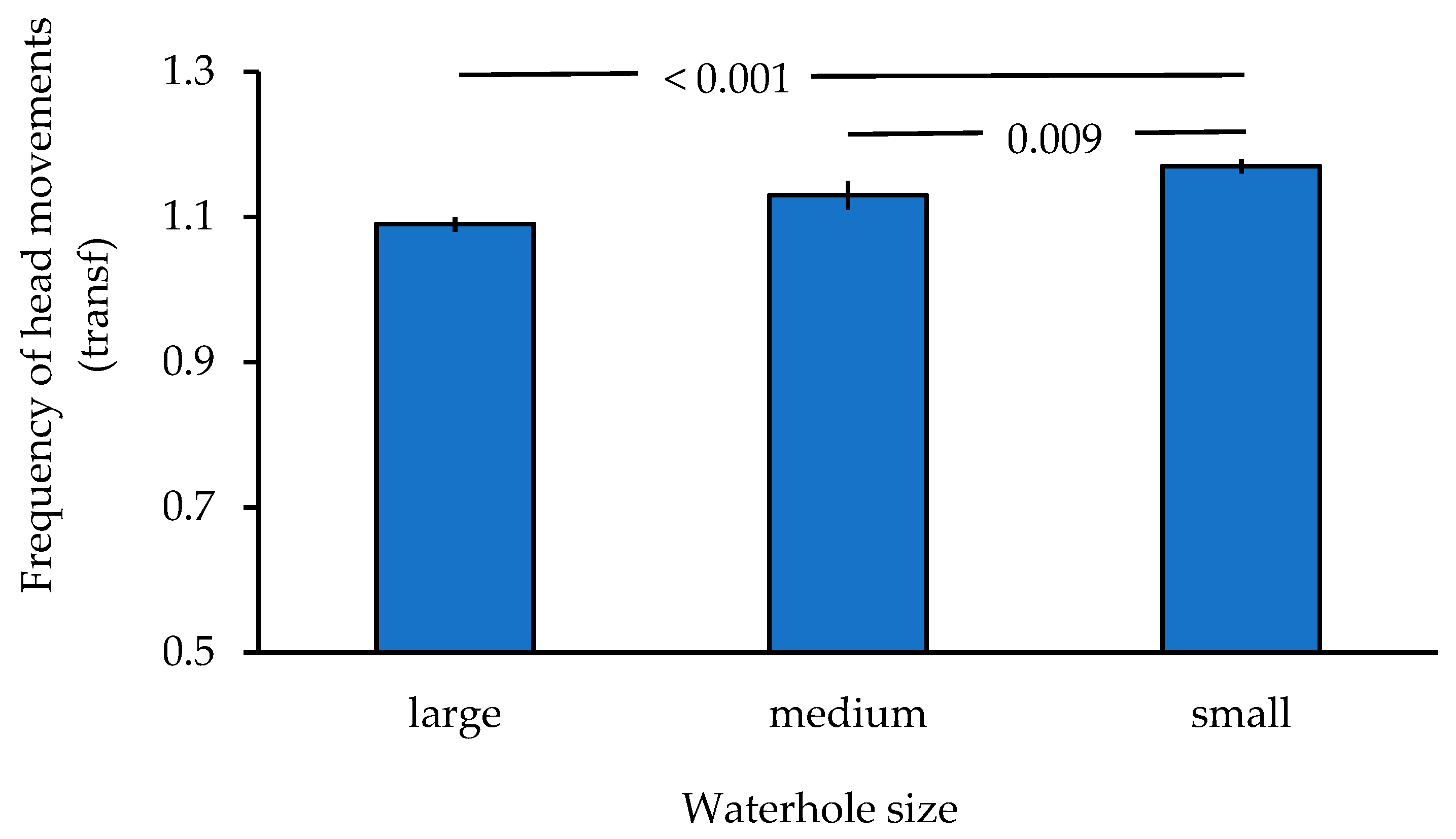

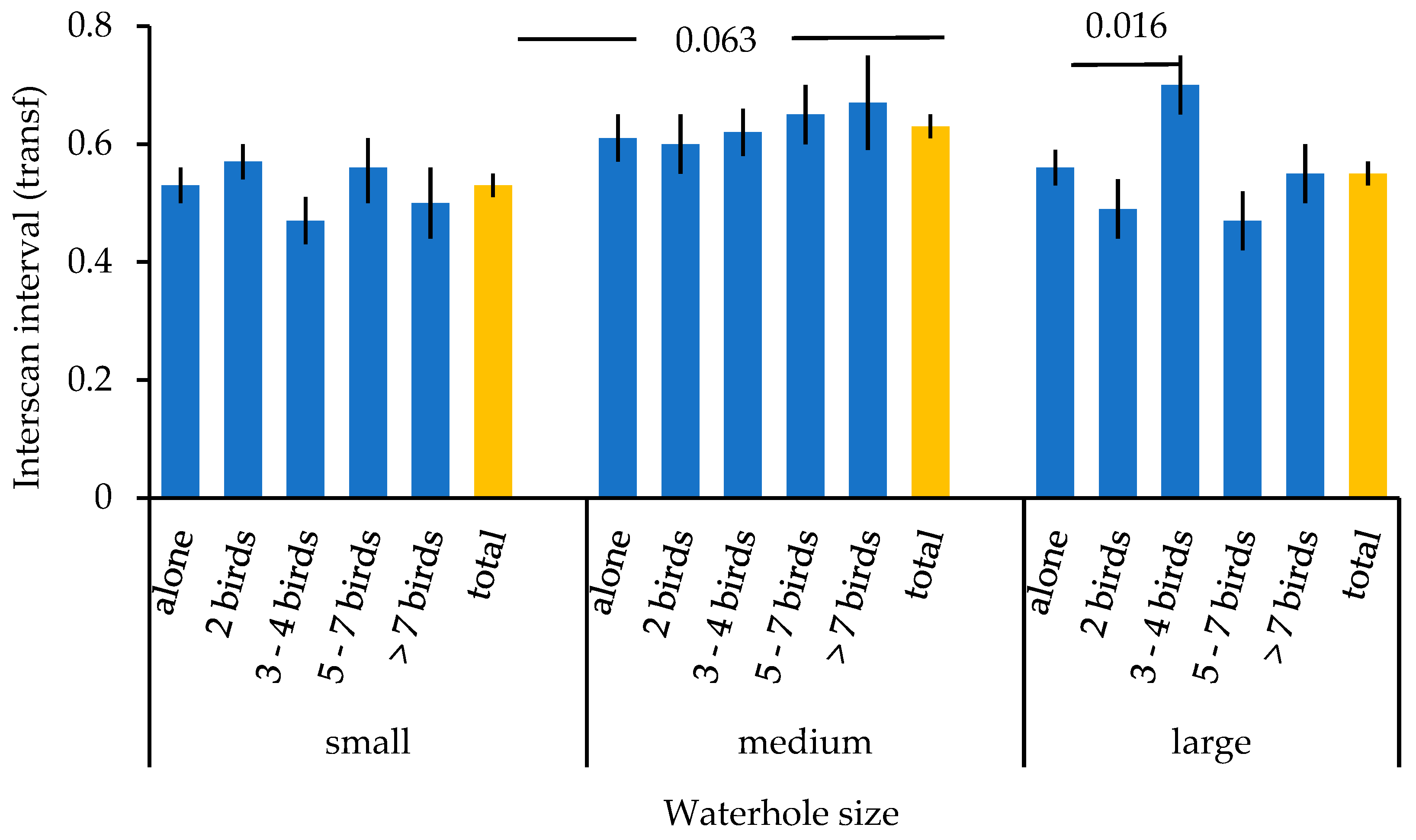

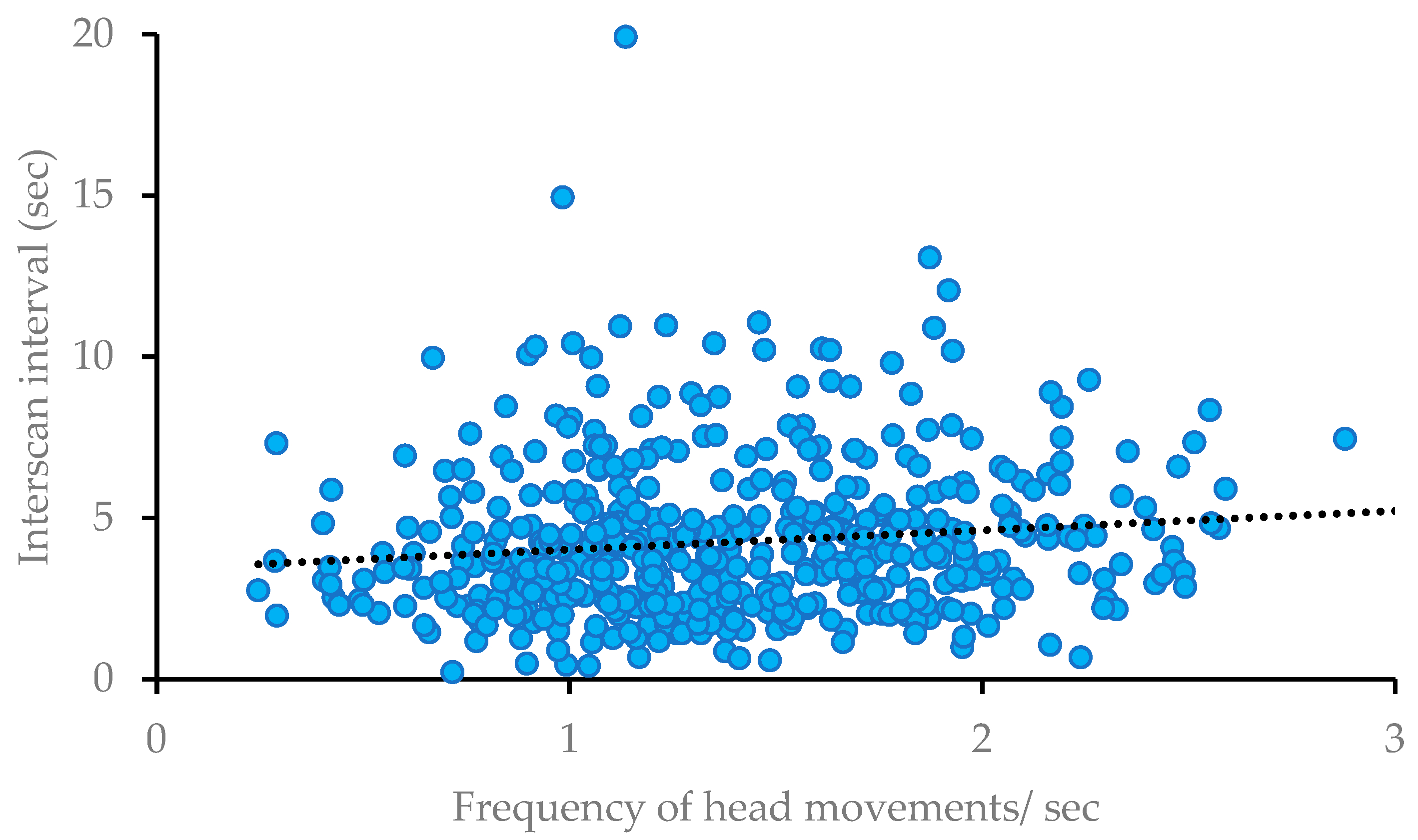

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Watson, M.; Aebischer, N.J.; Cresswell, W. Vigilance and fitness in grey partridges Perdix perdix: The effects of group size and foraging-vigilance trade-offs on predation mortality. J. Anim. Ecol. 2007, 76, 211–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Senar, J.C. Differential effects of predation risk and competition over vigilance variables and feeding success in Eurasian siskins (Carduelis spinus). Behaviour 2013, 150, 1665–1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, G. The effect of age on vigilance: A longitudinal study with a precocial species. Behaviour 2018, 155, 1011–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattorini, N.; Lovari, S.; Brunetti, C.; Baruzzi, C.; Cotza, A.; Macchi, E. Age, seasonality, and correlates of aggression in female Apennine chamois. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2018, 72, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.-M.; Lyu, N.; Sun, Y.-H.; Zhou, L.-Z. Number of neighbors instead of group size significantly affects individual vigilance levels in large animal aggregations. J. Avian Biol. 2019, 50, e02065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Stillman, R.A.; Smart, S.L.; Bullock, J.M.; Norris, K.J. Are the costs of routine vigilance avoided by granivorous foragers? Funct. Ecol. 2011, 25, 617–627. [Google Scholar]

- Stears, K.; Schmitt, M.H.; Wilmer, C.C.; Shrader, A.M. Mixed-species herding levels the landscape of fear. Proc. R. Soc. B 2020, 287, 20192555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blank, D.A. Vigilance, staring and escape running in antipredator behavior of goitered gazelle. Behav. Proc. 2018, 157, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Esattore, B.; Rossic, A.C.; Bazzonic, F.; Riggioc, C.; Oliveirac, R.; Leggieroc, I.; Ferretti, F. Erent time, head up: Multiple antipredator responses to a recolonizing apex predator. Curr. Zool. 2020, 69, 703–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannock, R.J.; Pays, O.; Renaud, P.-C.; Marond, M.; Goldizen, A.W. Assessing blue wildebeests’ vigilance, grouping and foraging responses to perceived predation risk using playback experiments. Behav. Proc. 2019, 164, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fattorini, N.; Ferretti, F. To scan or not to scan? Occurrence of the group-size effect in a seasonally nongregarious forager. Ethology 2019, 125, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hume, G.; Brunton, E.; Burnett, S. Eastern grey kangaroo (Macropus giganteus) vigilance behaviour varies between human-modified and natural environments. Animals 2019, 9, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carbone, C.; Thompson, W.A.; Zadorina, L.; Rowcliffe, J.M. Competition, predation risk and patterns of flock expansion in barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis). J. Zool. Lond. 2003, 259, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childress, M.J.; Lung, M.A. Predation risk, gender and the group size effect: Does elk vigilance depend upon the behaviour of conspecifics? Anim. Behav. 2003, 66, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimers, E.; Eftestol, S.; Colman, J.E. Vigilance in reindeer (Rangifer tarandus); evolutionary history, predation and human interference. Polar. Biol. 2021, 44, 997–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, W.; Quinn, J.L.; Whittingham, M.J.; Butler, S. Good foragers can also be good at detecting predators. Proc. R. Soc. B 2003, 270, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devereux, C.L.; Whittingham, M.J.; Fernandez-Juricic, E.; Vickery, J.A.; Krebs, J.R. Predator detection and avoidance by starlings under differing scenarios of predation risk. Behav. Ecol. 2006, 17, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, J.L.; Whittingham, M.J.; Butler, S.J.; Cresswell, W. Noise, predation risk compensation and vigilance in the chaffinch Fringilla coelebs. J. Avian Biol. 2006, 37, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Senar, J.C. Antipredator behavioural compensation of proactive personality trait in male Eurasian siskins. Anim. Behav. 2014, 90, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Senar, J.C.; Domenech, J. Plumage brightness, vigilance, escape potential, and predation risk in male and female Eurasian Siskins (Spinus spinus). Auk 2014, 131, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirot, E.; Pays, O. On the dynamics of predation risk perception for a vigilant forager. J. Theor. Biol. 2011, 276, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beale, C.M.; Monaghan, P. Behavioural responses to human disturbance: A matter of choice? Anim. Behav. 2004, 68, 1065–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Juricic, E. Sensory basis of vigilance behavior in birds: Synthesis and future prospects. Behav. Proc. 2012, 89, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, G.; Mettke-Hofmann, C. Watch out! High vigilance at small waterholes when alone in open trees. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, K.A.; Krebs, J.R.; Whittingham, M.J. Vigilance in the third dimension: Head movement not scan duration varies in response to different predator models. Anim. Behav. 2007, 74, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Juricic, E.; Beauchamp, G.; Treminio, R.; Hoover, M. Making heads turn: Association between head movements during vigilance and perceived predation risk in brown-headed cowbird flocks. Anim. Behav. 2011, 82, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griesser, M. Nepotistic vigilance behavior in Siberian jay parents. Behav. Ecol. 2003, 14, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, E.R.; van Deelen, T.R. Competition and sex-age class alter the effects of group size on vigilance in white-tailed deer Odocoileus virginianu. Acta Ethol. 2024, 27, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, M.; Blank, D.; Alves da Silva, A.; Yang, W.; Ruckstuhl, K.E.; Alves, J. Goitered gazelle Gazella subgutturosa responded to human disturbance by increasing vigilance rather than changing the group size. Biology 2022, 11, 1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J. Visibility, group size, vigilance, and drinking behavior in coati (Nasua narica) and white-faced capuchins (Cebus capucinus): Experimental evidence. Acta Ethol. 2001, 3, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Luo, W.; Pape Moller, A.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X. Vigilance strategy differentiation between sympatric threatened and common crane species. Behav. Proc. 2020, 176, 104119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecorella, I.; Fattorini, N.; Macchi, E.; Ferretti, F. Sex/age differences in foraging, vigilance and alertness in a social herbivore. Acta Ethol. 2019, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taraborelli, P.; Moreno, P.; Mosca Torres, M.E. Are there different vigilance strategies between types of social units in Lama guanicoe? Behav. Proc. 2019, 167, 103914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Zhuom, C.J.; Li, Z. Group size effects on vigilance of wintering Black-necked cranes (Grus nigricollis) in Tibet, China. Waterbird 2016, 39, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashley, M.A.; Chitwood, C.; Biggerstaff, M.T.; Morina, D.L.; Moorman, C.E.; DePerno, C.S. White-tailed deer vigilance: The influence of social and environmental factors. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangle, W.M.; Holekamp, K.E. Functions of vigilance behaviour in a social carnivore, the spotted hyaena, Crocuta crocuta. Anim Behav. 2010, 80, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burger, J.; Gochfeld, M. Effect of group size on vigilance while drinking in the coati, Nasua narica in Costa Rica. Anim. Behav. 1992, 44, 1053–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi-Gomez, C.; Valdivieso-Cortadella, S.; Llorente, M.; Aureli, F.; Amici, F. Vigilance has mainly a social function in a wild group of spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi). Am. J. Primatol. 2023, 85, e23559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klose, S.M.; Welbergen, J.A.; Goldizen, A.W.; Kalko, E.K.V. Spatio-temporal vigilance architecture of an Australian flying-fox colony. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2009, 63, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, L.M.; Fedigan, L.M. Vigilance in white-faced capuchins, Cebus capucinus, in Costa Rica. Anim. Behav. 1995, 49, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoist, S.; Garel, M.; Cugnasse, J.-M.; Blanchard, P. Human disturbances, habitat characteristics and social environment generate sex-specific responses in vigilance of Mediterranean mouflon. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monclus, R.; Roedel, H.G. Influence of different individual traits on vigilance behaviour in European rabbits. Ethology 2009, 115, 758–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Blank, D.; Wang, M.; Yanget, W. Vigilance behaviour in Siberian ibex (Capra sibirica): Effect of group size, group type, sex and age. Behav. Proc. 2020, 170, 104021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flamand, A.; Rebout, N.; Bordes, C.; Guinnefollau, L.; Berges, M.; Ajak, F. Hamsters in the city: A study on the behaviour of a population of common hamsters (Cricetus cricetus) in urban environment. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0225347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieucau, G.; Blanchard, P.; Martin, J.G.A.; Favreau, F.-R.; Goldizen, A.W.; Pays, O. Investigating differences in vigilance tactic use within and between the sexes in Eastern Grey Kangaroos. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e44801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberts, S.C. Vigilance in young baboons: Effects of habitat, age, sex and maternal rank on glance rate. Anim. Behav. 1994, 47, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, D.F.; Chamaille-Jammes, S.; Shrader, A.M. Herbivores employ a suite of antipredator behaviours to minimize risk from ambush and cursorial predators. Anim. Behav. 2017, 127, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courbin, N.; Loveridge, A.J.; Macdonald, D.W.; Fritz, H.; Valeix, M.; Makuwe, E.T.; Chamaillé-Jammes, S. Reactive responses of zebras to lion encounters shape their predator–prey space game at large scale. Oikos 2015, 125, 829–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosmary, W.-G.; Valeixa, M.; Fritza, H.; Madzikandad, H.; Côté, S.D. African ungulates and their drinking problems: Hunting and predation risks constrain access to water. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periquet, S.; Valeix, M.; Loveridge, A.J.; Madzikanda, H.; Macdonald, D.W.; Fritz, H. Individual vigilance of African herbivores while drinking: The role of immediate predation risk and context. Anim. Behav. 2010, 79, 665–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosmary, W.G.; Makumbe, P.; Cote, S.D.; Fritz, H. Vulnerability to predation and water constraints limit behavioural adjustments of ungulates in response to hunting risk. Anim. Behav. 2012, 83, 1367–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valeix, M.; Fritz, H.; Loveridge, A.J.; Davidson, Z.; Hunt, J.E.; Murindagomo, F.; Macdonald, D.W. Does the risk of encountering lions influence African herbivore behaviour at waterholes? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2009, 63, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrascal, L.M.; Alonso, C.L. Habitat use under latent predation risk. A case study with wintering forest birds. Oikos 2006, 112, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taette, K.; Ibanez-Alamo, J.D.; Marko, G.; Maend, R.; Moeller, A.P. Antipredator function of vigilance re-examined: Vigilant birds delay escape. Anim. Behav. 2019, 156, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-M.; Xie, W.-T.; Shuai, L.-Y. Flush early and avoid the rush? It may depend on where you stand. Ethology 2020, 126, 987–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, A. Habitat use and space preferences of Eurasian Bullfinches (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) in northwestern Iberia throughout the year. Avian Res. 2021, 12, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Votto, S.E.; Schlesinger, C.; Dyer, F.; Caron, V.; Davis, J. The role of fringing vegetation in supporting avian access to arid zone waterholes. Emu Austral Orn. 2022, 122, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kullberg, C.; Lafrenz, M. Escape take-off strategies in birds: The significance of protective cover. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2007, 61, 1555–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumstein, D.T.; Fernandez-Juricic, E.; LeDee, O.; Larsen, E.; Rodriguez-Prieto, I.; Zugmeyer, C. Avian risk assessment: Effects of perching height and detectability. Ethology 2004, 110, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, G.; Mettke-Hofmann, C. Conspicuous animals remain alert when under cover but do not differ in the temporal course of vigilance from less conspicuous species. Animals 2025, 15, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamanda, M.; Ndiweni, V.; Imbayarwo-Chikosi, V.E.; Muvengwi, J. The impact of tourism on sable antelope (Hippotragus niger) vigilance behavior at artificial waterholes during the dry season in Hwange National Park. J. Sust. Dev. Afr. 2008, 10, 299–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dostine, P.L.; Johnson, G.C.; Franklin, D.C.; Zhang, Y.; Hempel, C. Seasonal use of savanna landscapes by the Gouldian finch, Erythrura gouldiae, in the Yinberrie Hills area, Northern Territory. Wildl. Res. 2001, 28, 445–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazill-Boast, J.; Dessmann, J.K.; Davies, G.T.O.; Pryke, S.R.; Griffith, S.C. Selection of breeding habitat by the endangered Gouldian Finch (Erythrura gouldiae) at two spatial scales. Emu 2011, 111, 304–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Christie, D.A. Handbook of the Birds of the World: Weavers to New World Warblers; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 2010; Volume 15. [Google Scholar]

- Del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. Handbook of the Birds of the World: New World Vultures to Guineafowl; Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Brush, A.H.; Seifried, H. Pigmentation and feather structure in genetic variants of the Gouldian finch, Poephila gouldiae. Auk Ornithol. Adv. 1968, 85, 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NT Government. Threatened Species of the Northern Territory. 2021. Available online: https://nt.gov.au/environment/animals/threatened-animals (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- 68; Diniz, P. Sex-dependent foraging effort and vigilance in coal-crested finches, Charitospiza eucosma (Aves: Emberizidae) during the breeding season: Evidence of female-biased predation? Zoologia 2011, 28, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Brazill-Boast, J.; Pryke, S.R.; Griffith, S.C. Nest-site utilisation and niche overlap in two sympatric, cavity-nesting finches. Emu 2010, 110, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.M.; Collins, J.A.; Evans, R.; Miller, S. Patterns of drinking behaviour of some Australian estrildine finches. Ibis 1985, 127, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBM. Bootstrapping 28. 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/SSLVMB_28.0.0/pdf/IBM_SPSS_Bootstrapping.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- IBM. Omnibus Test. 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/docs/en/spss-statistics/29.0.0?topic=models-omnibus-test (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Australian Government. Australia’s National Climate Risk Assessment. 2025. Available online: https://www.preventionweb.net/media/110589/download?startDownload=20251228 (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Beauchamp, G. External body temperature and vigilance to a lesser extent track variation in predation risk in domestic fowls. BMC Zoology 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, A.O.; Hofmann, G.; Mettke-Hofmann, C. Gouldian finches are followers with blackheaded females taking the lead. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0214531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertram, B.C.R. Living in groups: Predators and prey. In Behavioural Ecology: An Evolutionary Approach; Krebs, J.R., Davies, N.B., Eds.; Blackwell Scientific: Oxford, UK, 1978; pp. 64–96. [Google Scholar]

| Distance Between Adjacent Sites (km) | Waterhole Size | Recording Method | Number of Birds Sampled 2023 | Number of Birds Sampled 2024 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 * | small | D (2023) & V (2024) | 142 | 128 ** |

| 2 | 11.1 | medium | D & V | 94 | |

| 3 | 13.8 | large | D | 58 | |

| 4 | 1.5 | small | D | 30 | |

| 5 | 8.6 | medium | D | 26 | |

| 6 | 38.8 | large | D | 7 | |

| 7 | 11.7 | large | D & V | 21 | 98 |

| 8 | 80.6 | medium | D | 34 | |

| 9 | small | D | 10 |

| Variable | df | F-Value | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrected model | 2 | 210.567 | <0.001 |

| Intercept | 1 | 12.331 | <0.001 |

| Vertical level | 2 | 210.567 | <0.001 |

| Variable | df | Chi-Square | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 989.105 | <0.001 |

| Waterhole size | 2 | 27.515 | <0.001 |

| Year | 1 | 425.567 | <0.001 |

| Variable | Df | Chi-Square | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1 | 99.738 | <0.001 |

| Waterhole size | 2 | 12.398 | 0.002 |

| Group size | 4 | 1.788 | 0.775 |

| Waterhole size x group size | 8 | 18.198 | 0.020 |

| Year | 1 | 8.960 | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hofmann, G.; Mettke-Hofmann, C. Gouldian Finches (Chloebia gouldiae) Increase the Frequency of Head Movements with Increasing Risk at Water-holes but Prolong Interscan Intervals While Drinking: Two Different Strategies? Animals 2026, 16, 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010087

Hofmann G, Mettke-Hofmann C. Gouldian Finches (Chloebia gouldiae) Increase the Frequency of Head Movements with Increasing Risk at Water-holes but Prolong Interscan Intervals While Drinking: Two Different Strategies? Animals. 2026; 16(1):87. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010087

Chicago/Turabian StyleHofmann, Gerhard, and Claudia Mettke-Hofmann. 2026. "Gouldian Finches (Chloebia gouldiae) Increase the Frequency of Head Movements with Increasing Risk at Water-holes but Prolong Interscan Intervals While Drinking: Two Different Strategies?" Animals 16, no. 1: 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010087

APA StyleHofmann, G., & Mettke-Hofmann, C. (2026). Gouldian Finches (Chloebia gouldiae) Increase the Frequency of Head Movements with Increasing Risk at Water-holes but Prolong Interscan Intervals While Drinking: Two Different Strategies? Animals, 16(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010087