A Hypothesis of Gut–Liver Mediated Heterosis: Multi-Omics Insights into Hybrid Taimen Immunometabolism (Hucho taimen ♀ × Brachymystax lenok ♂)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Methods

2.2. Gut Microbiome Analysis

2.3. Intestinal and Liver Transcriptome Analysis

2.4. qRT-PCR

3. Results

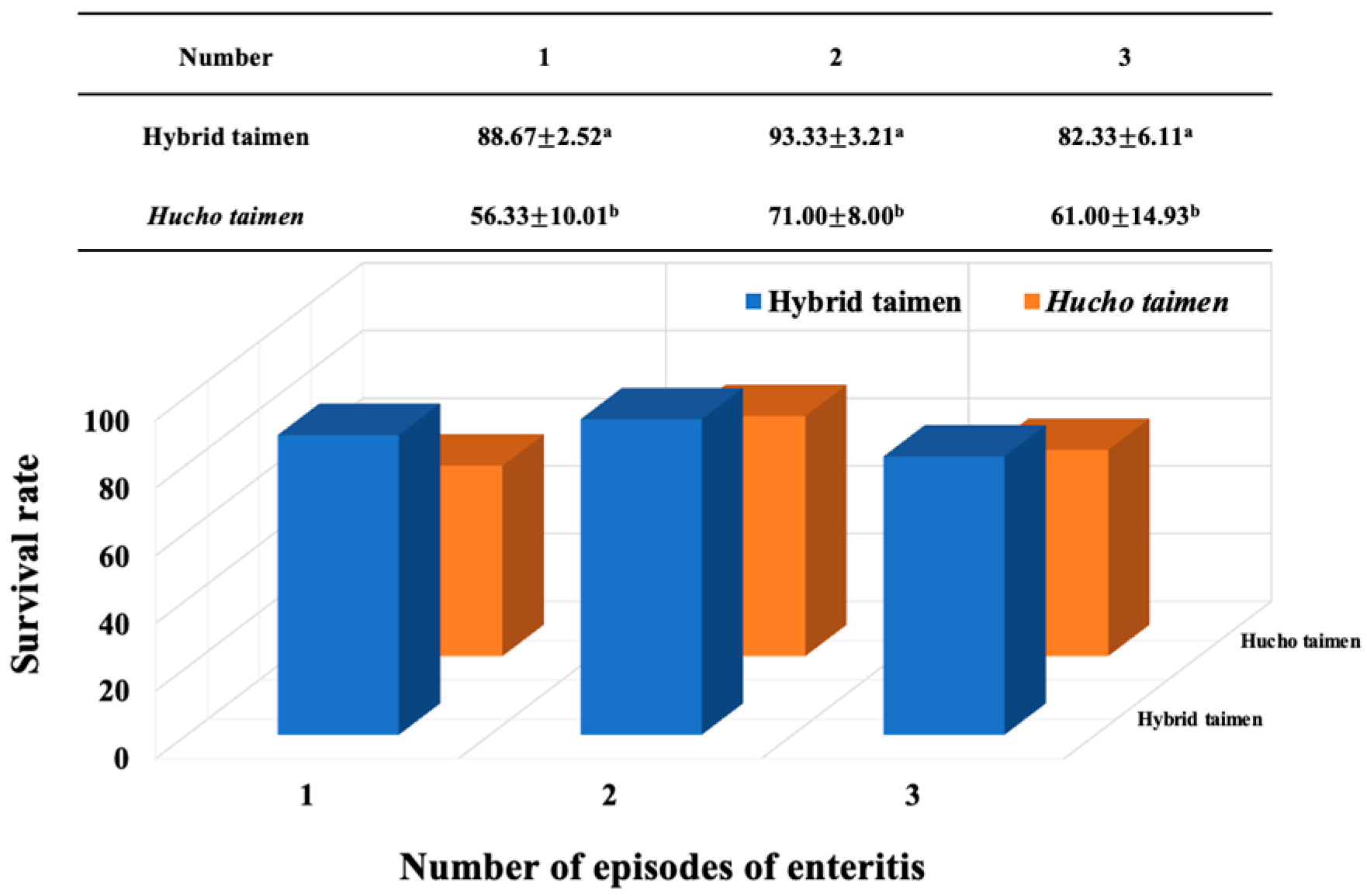

3.1. Survival Rates of Intestinal Inflammation in Hybrid Taimen Versus Hucho taimen

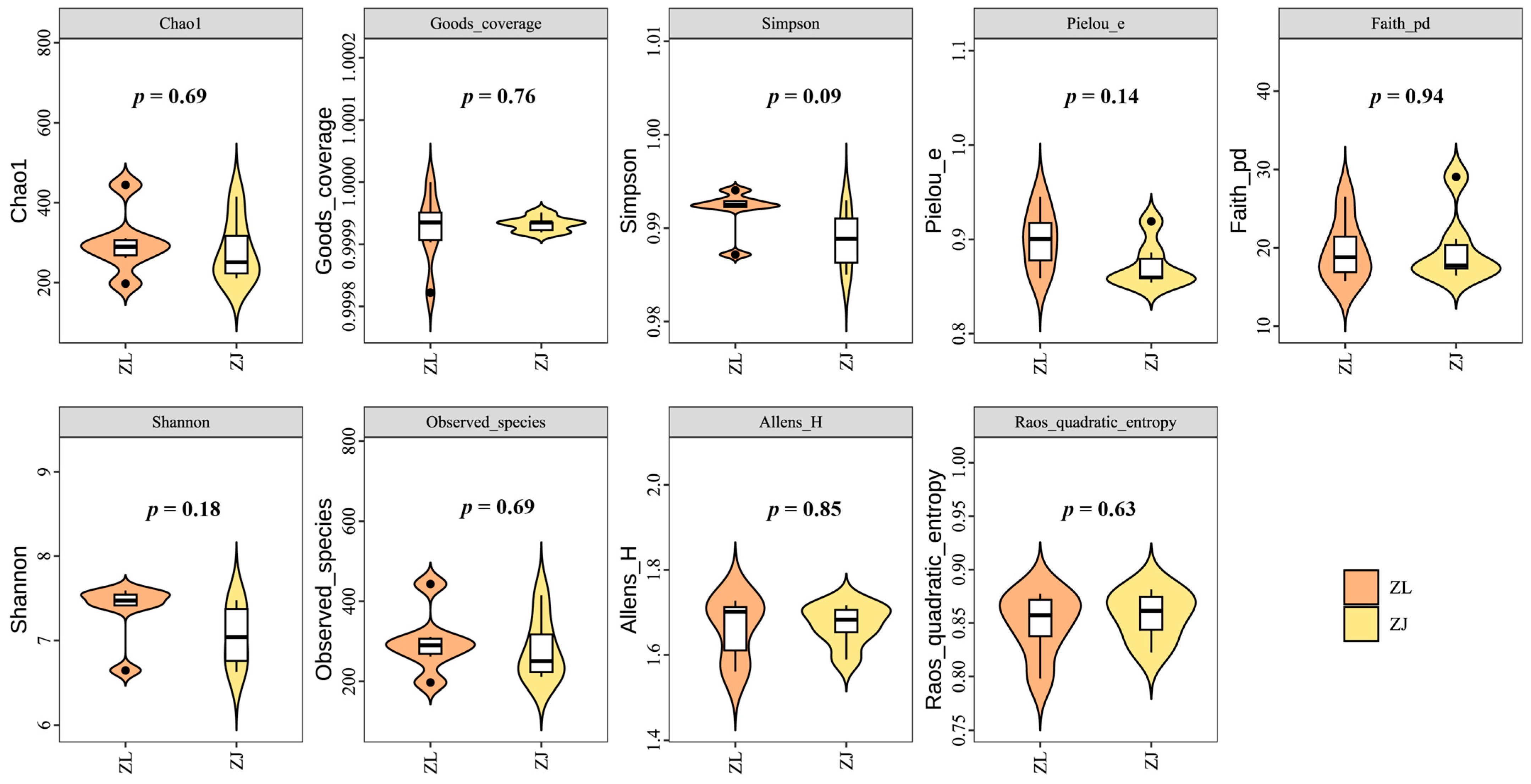

3.2. Abundance and Diversity of Microbial Communities

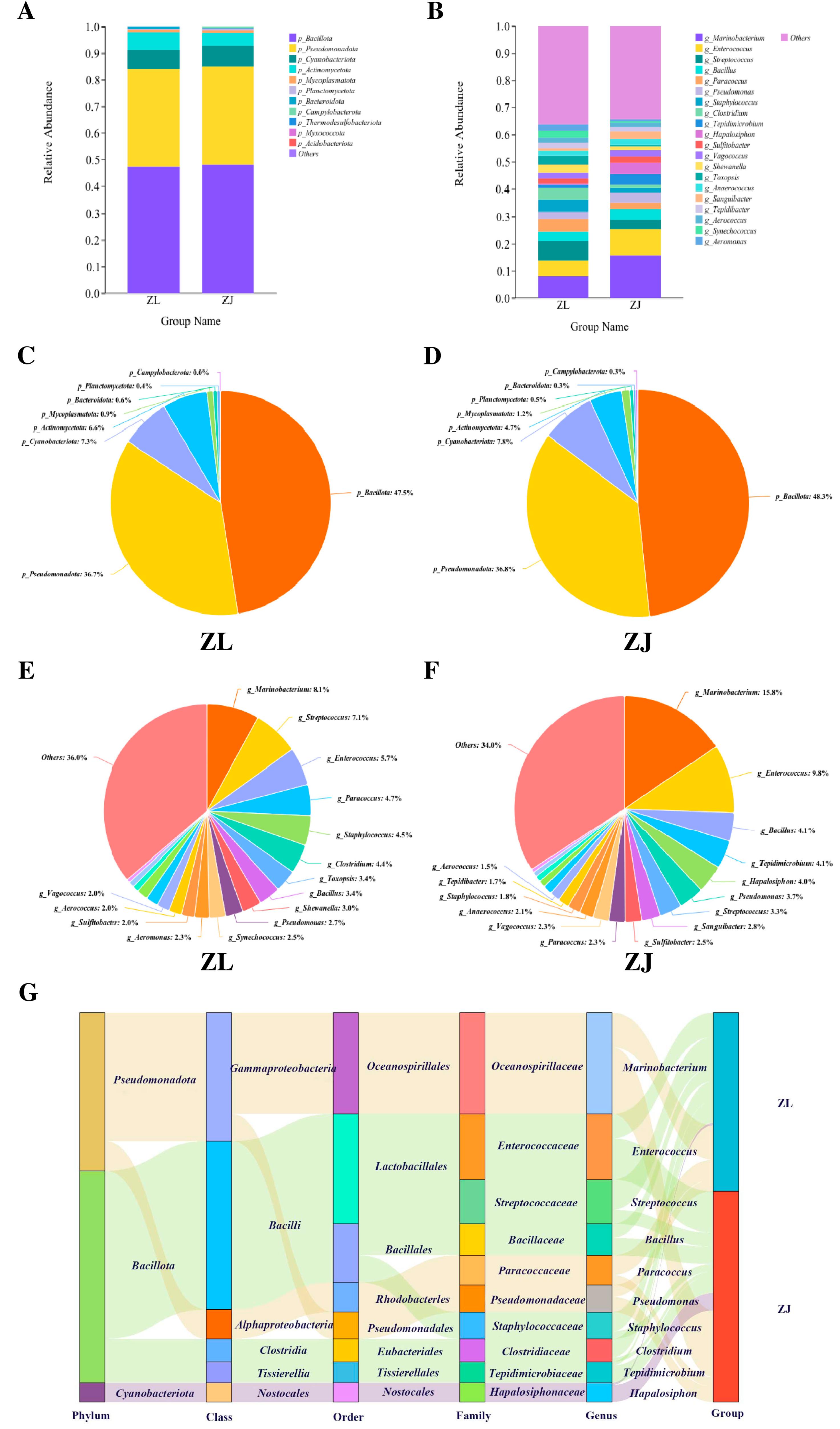

3.3. Microbial Community Composition

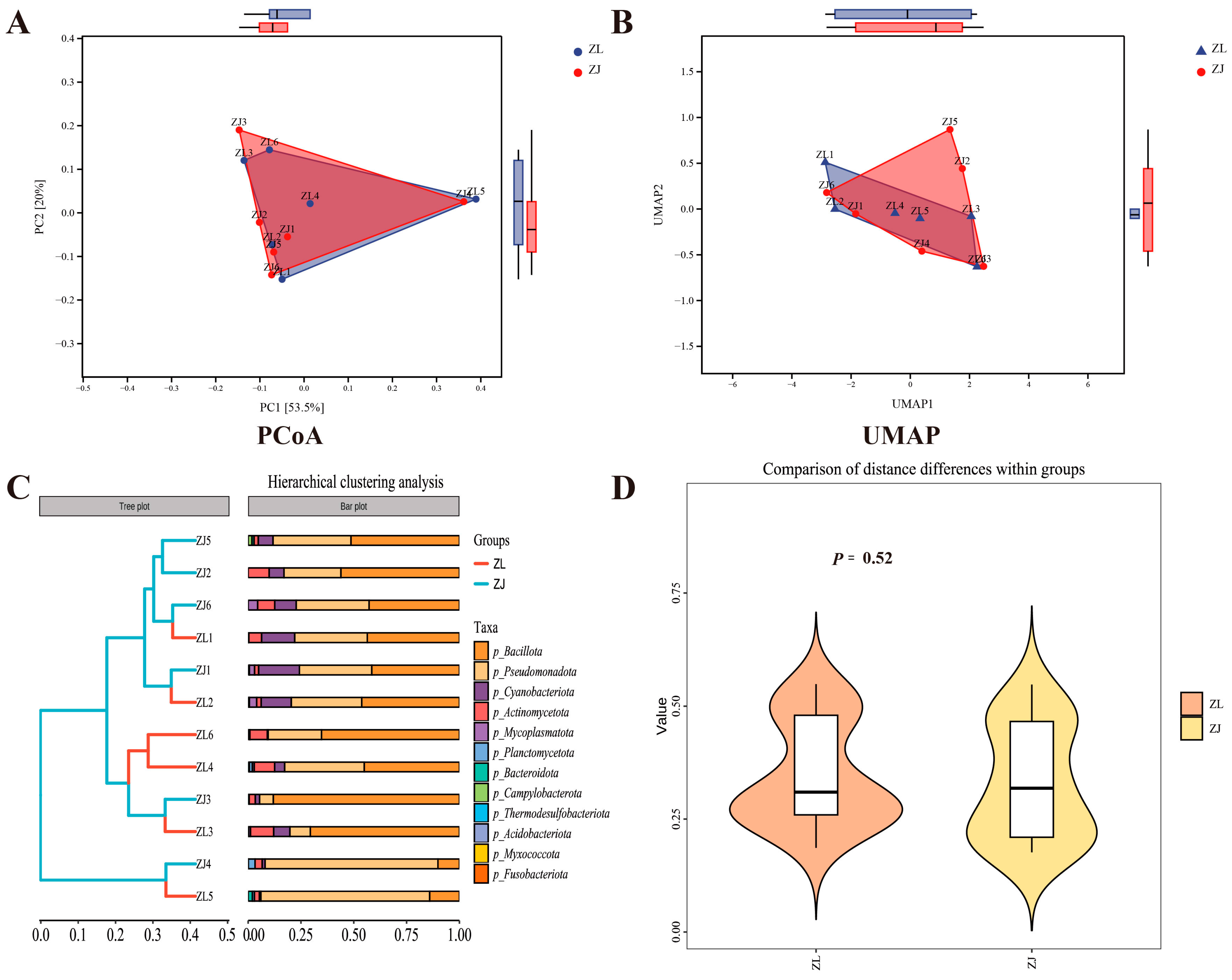

3.4. Microbial Community Structure Shifts

3.5. Functional Prediction of Gut Microbiota

3.6. Transcriptome Analysis of Liver and Intestinal Tissues

3.6.1. Identification of DEGs

3.6.2. Functional Enrichment Analysis Based on GSEA

3.6.3. qRT-PCR Analysis

4. Discussion

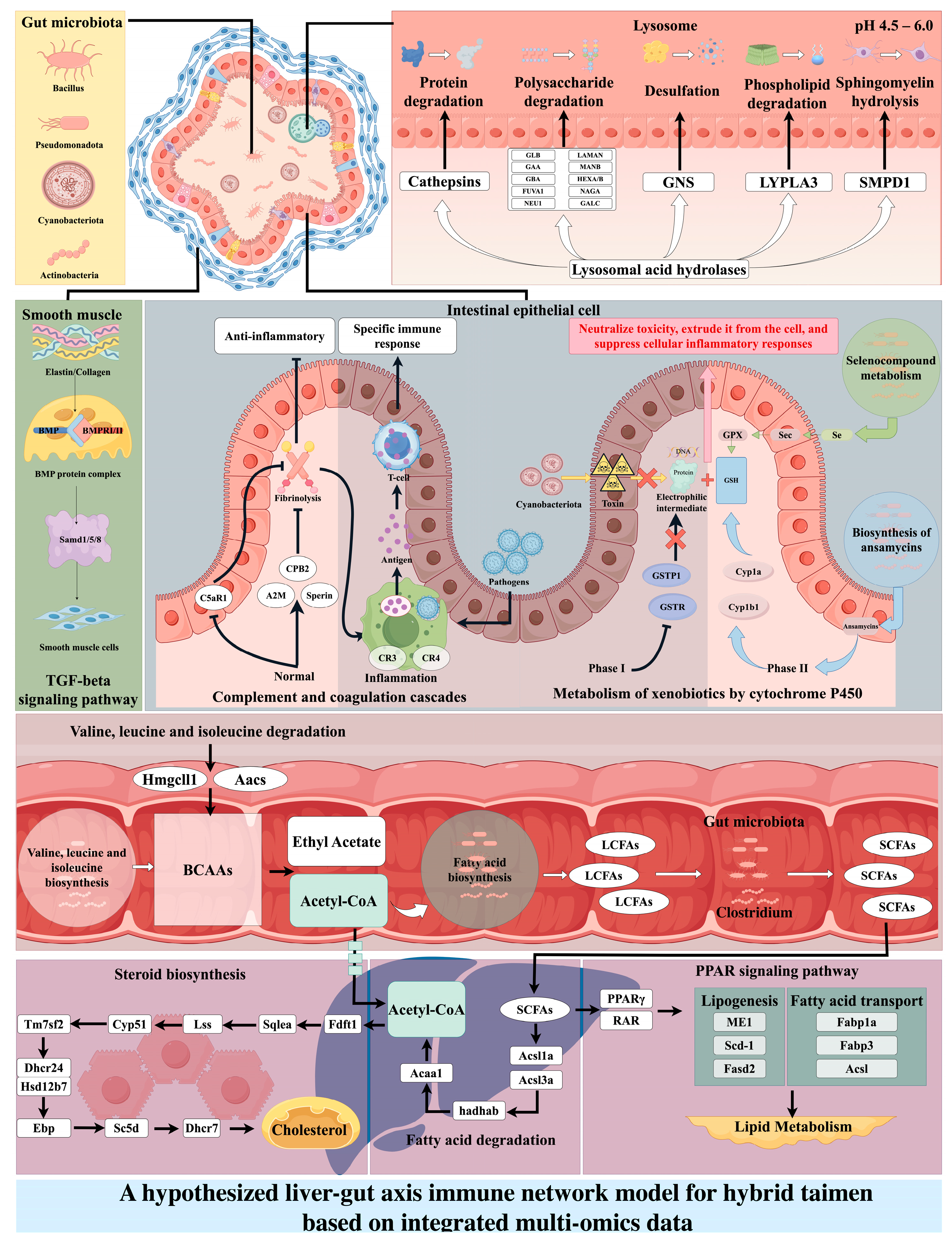

4.1. A Multi-Level Synergistic Mechanism of Intestinal Immunity in Hybrid taimen

4.2. Potential Roles of Gut Microbiota in Shaping Immune Function of Hybrid taimen

4.3. Omics-Guided Hypothesis: Gut–Liver Axis Ignition of Cholesterol Synthesis as a Metabolic Edge in Hybrid taimen

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ZL | Hucho taimen |

| ZJ | Hybrid taimen |

| ZLC | Intestinal tissue of Hucho taimen |

| ZJC | Intestinal tissue of Hybrid taimen |

| ZLG | Liver tissue of Hucho taimen |

| ZJG | Liver tissue of Hybrid taimen |

| RAS | Recirculating Aquaculture System |

| GSEA | Gene Set Enrichment Analysis |

| SCFAs | Short-Chain Fatty Acids |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| TGF-β | Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| PPAR | Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor |

| VU | Vulnerable |

| IUCN | International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| KEGG | Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes |

| PCoA | Principal Coordinates Analysis |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| ASVs | Operational Taxonomic Units |

| LEfSe | Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| fasd | fas-associated via death domain |

| dpep1 | dipeptidase 1 |

| a2m | alpha-2-macroglobulin |

| serpin | serine protease inhibitor |

| cyp1b1 | cytochrome P450 family one subfamily B member 1 |

| acsf2 | acyl-CoA synthetase family member 2 |

| ECM | Extracellular Matrix protein |

| bmps | bone morphogenetic proteins |

| bmprI/II | BMP receptors I/II |

| smad1/5/8 | small mothers against decapentaplegic 1/5/8 |

| cr3 | complement receptor 3 |

| cr4 | complement receptor 4 |

| c5ar1 | complement 5a receptor 1 |

| cpb2 | carboxypeptidase B2 |

| tnf-α | tumour necrosis factor-alpha |

| il-6 | interleukin-6 |

| cyp1a | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily A |

| cyp1b1 | cytochrome P450 family 1 subfamily B member 1 |

| gstp1 | glutathione S-transferase pi 1 |

| gstt1 | glutathione S-transferase theta 1 |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| Sec | Selenocysteine |

| gpx | glutathione peroxidase |

| pgd2 | prostaglandin d2 |

| hpgds | hematopoietic Prostaglandin D Synthase |

| ICSP | International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes |

| BCAAs | branched-chain amino acids |

| hmgcll1 | 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA lyase-like 1 |

| AACS | Acetoacetyl-CoA Synthetase |

| TCA | Tricarboxylic Acid |

| acsl1a | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 1a |

| acsl3a | acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 3a |

| hadhab | hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase trifunctional multienzyme complex subunit alpha B |

| acaa1 | acetyl-CoA acyltransferase 1 |

| fdft1 | arnesyl diphosphate farnesyltransferase 1 |

| sqlea | squalene synthase |

| lss | lateral splicing site |

| cyp51 | cytochrome P450 family 51 |

| tm7sf2 | transmembrane 7 superfamily domain-containing protein 2 |

| pparγ | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ |

| rar | retinoic acid receptor |

| scd-1 | stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 |

| cyp27 | cytochrome P450 family 27 |

References

- Tong, G.X.; Xue, S.Q.; Geng, L.W.; Zhou, Y.; Yin, J.; Sun, Z.R.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Han, Y.; Kuang, Y.Y. First high-resolution genetic linkage map of taimen (Hucho taimen) and its application in QTL analysis of growth-related traits. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Kuang, Y.Y.; Tong, G.X.; Yin, J.S. Genetics analysis on incompatibility of intergeneric hybridizations between Hucho taimen(♂) and Brachymystax lenok(♀) by using 30 polymorphic SSR markers. J. Fish. Sci. China 2013, 18, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuciński, M.; Fopp-Bayat, D. Phylogenetic analysis of Brachymystax and Hucho genera—Summary on evolutionary status within the Salmoninae subfamily. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2022, 38, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Niu, L.; Chang, J.B.; Kou, X.M.; Wang, W.T.; Hu, W.J.; Liu, Q.G. Population genomic analysis reveals genetic divergence and adaptation in Brachymystax lenok. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1293477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.X.; Tong, G.X.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Wang, X.J.; Qi, P.; Yin, J.S. Study on large-scale breeding on hybrids of Hucho taimen (♀) ×Brachymystax lenok (♂) and its growth characters. Freshw. Fish. 2015, 45, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.F.; Huang, T.Q.; Gu, W.; Wang, B.Q. Comparison of Muscular Fatty Acid Composition and Level Among Reared Lenok Brachymystax lenok, Taimen Hucho taimen and their Hybrid. Chin. J. Fish. 2018, 31, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Yu, D.; Zheng, S.J.; Ouyang, R.; Wang, Y.T.; Xu, G.W. Gut microbiota-related metabolome analysis based on chromatography-mass spectrometry. Trends Anal. Chem. 2021, 143, 116375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Guo, X.W.; Gooneratne, R.; Lai, R.F.; Zeng, C.; Zhan, F.B.; Wang, W.M. The gut microbiome and degradation enzyme activity of wild freshwater fishes influenced by their trophic levels. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 24340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbis, C.R.; Rawlin, G.T.; Mitchell, G.F.; Anderson, J.W.; McCauley, I. The histopathology of carp, Cyprinus carpio L., exposed to microcystins by gavage, immersion and intraperitoneal administration. J. Fish Dis. 1996, 19, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Xie, P.; Chen, J. In vivo studies on toxin accumulation in liver and ultrastructural changes of hepatocytes of the phytoplanktivorous bighead carp i.p.-injected with extracted microcystins. Toxicon 2005, 46, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, D.C.; Passos, S.L.; Freitas, d.N.N.P.; Souza, d.O.A.; Pinto, E. Impacts of Cyanobacterial metabolites on fish: Socioeconomic and environmental considerations. Rev. Aquac. 2024, 16, 1186–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, J.; Xia, R.J.; Kim, M.A.; Oblie, N.; Hefferan, S.; Xie, H.; Slitt, A.; Jenkins, D.B.; Bertin, J.M. Temporal Dynamics of Cyanobacterial Bloom Community Composition and Toxin Production from Urban Lakes. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 3423–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chilczuk, T.; Steinborn, C.; Breinlinger, S.; Zimmermann-Klemd, M.A.; Huber, R.; Enke, H.; Enke, D.; Niedermeyer, J.H.T.; Gründemann, C. Hapalindoles from the Cyanobacterium Hapalosiphon sp. Inhibit T Cell Proliferation. Planta Medica 2019, 86, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.S.; Qi, Y.Q.; Wang, L.D.; Zhang, Y.N.; Chen, H.Q.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Min, H.; Nie, G.J.; Liang, H.X. Lysosome-Targeting Nanochimeras Attenuating Liver Fibrosis by Interconnected Transforming Growth Factor-β Reduction and Activin Receptor-Like Kinase 5 Degradation. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 25645–25661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, A.; Pettinato, M.; Dulja, A.; Colucci, S.; Aghajan, M.; Furiosi, V.; Muckenthaler, U.M.; Guo, S.L.; Nai, A.; Silvestri, L. Dissecting the Mechanisms of Hepcidin and BMP-SMAD Pathway Regulation By FKBP12. Blood 2021, 138, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Zhang, X.M.; Xu, J.Q.; Luo, R.; Li, S.; Su, H.; Wang, Q.S.; Hou, L.Y. Complement Receptor 3 Regulates Microglial Exosome Release and Related Neurotoxicity via NADPH Oxidase in Neuroinflammation Associated with Parkinson’s Disease. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.C.; Choi, Y.I.; Bok, E.; Lin, Y.X.; Cheon, M.Y.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, J.W. Complement receptor 4 mediates the clearance of extracellular tau fibrils by microglia. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 3499–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, L.; Poire, A.; Jeong, J.K.; Zhang, D.; Ozmen, T.Y.; Chen, G.; Sun, C.Y.; Mills, G.B. C5aR1 inhibition reprograms tumor associated macrophages and reverses PARP inhibitor resistance in breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Li, Y.S.; Yang, K.; Lü, T.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.H.; Liu, C.; Yu, M.; Wang, M.N.; Cheng, Z.B.; et al. Regulatory Effects of SLC7A2-CPB2 on Lymphangiogenesis: A New Approach to Suppress Lymphatic Metastasis in HNSCC. Cancer Med. 2024, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, P. Alpha-2-Macroglobulin Mitigates Glucocorticoid-Induced Osteonecrosis via Keap1/Nrf2 Pathway Activation. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2024, 225, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.S.; Bao, J.L.; Li, B.N.; Shi, Y.L.; Yang, W.X.; Meng, X.Z.; Chen, J.; Wei, J.H.; Long, M.X.; Li, T.; et al. Microsporidian Nosema bombycis secretes serine protease inhibitor to suppress host cell apoptosis via Caspase BmICE. PLoS Pathog. 2025, 21, e1012373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, C.; Handa, N.; Hao, Y.Y.; Alshalalfa, M.; Alexander, K.; Hakansson, J.; Davicioni, E.; Ashley, E.R.; William, J.C.; Matthew, R.C.; et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha signaling activity and NCCN risk, adverse pathology, and progression during active surveillance in prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahab, N.; Anouti, B.; Basu, S.; Zhang, Y.W.; Bentebibel, S.; Abdel-Wahab, R.; Cho, S.; Nurieva, R.; Allison, J.P.; Ekmekçioğlu, S.; et al. Interrogating the interleukin-6 (IL-6)/IL-23/T-helper (Th)17 axis in immunotherapy toxicity: Mechanistic insights and therapeutic implications. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, 12134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.H.; Dang, W.W.; Wang, C.M. Lysosomes signal through the epigenome to regulate longevity across generations. Science 2025, 389, 1353–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Roy, C.; Allison, A.C. Changes in Cellular Enzyme Levels and Extracellular Release Of Lysosomal Acid Hydrolases in Macrophages Exposed to Group A Streptococcal Cell Wall Substance. J. Exp. Med. 1974, 139, 1262–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Cho, Y.S.; Jung, Y.K. Failure of lysosomal acidification and endomembrane network in neurodegeneration. Exp. Mol. Med. 2025, 57, 2418–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorgen-Ritchie, M.; Clarkson, M.; Chalmers, L.; Taylor, J.F.; Migaud, H.; Martin, S.A.M. A Temporally Dynamic Gut Microbiome in Atlantic Salmon During Freshwater Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) Production and Post-seawater Transfer. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 2296–7745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- August, R.P.; Tang, L.; Yoon, J.Y.; Ning, S.; Müller, R.; Yu, T.Y.; Taylor, M.; Hoffmann, D.; Kim, C.G.; Zhang, X.H.; et al. Biosynthesis of the ansamycin antibiotic rifamycin: Deductions from the molecular analysis of the rif biosynthetic gene cluster of Amycolatopsis mediterranei S699. Chem. Biol. 1998, 5, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihlaja, T.L.M.; Niemissalo, S.M.; Sikanen, T.M. Cytochrome P450 inhibition by antimicrobials and their mixtures in rainbow trout liver microsomes in vitro. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2022, 41, 663–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bian, D.D.; Jiang, Q.; Jiang, J.J.; Jin, Y.; Chen, F.X.; Zhang, D.Z.; Liu, Q.N.; Tang, B.P.; Dai, L.S. Insights into chlorantraniliprole exposure via activating cytochrome P450-mediated xenobiotic metabolism pathway in the Procambarus clarkii: Identification of P450 genes involved in detoxification. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, R.; Dalvie, K.D. Cytochrome P450 and Non-Cytochrome P450 Oxidative Metabolism: Contributions to the Pharmacokinetics, Safety, and Efficacy of Xenobiotics. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2016, 44, 1229–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajaud, J.; Ribault, C.; Mosbah, B.I.; Raush, C.; Henderson, C.; Bellaud, P.; Aninat, C.; Loyer, P.; Morel, F.; Corlu, A. Glutathione transferases P1/P2 regulate the timing of signaling pathway activations and cell cycle progression during mouse liver regeneration. Cell Death Dis. 2015, 6, e1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.S.; Wang, J.N.; Qu, Y.L.; Ning, J.; Zhang, Y.T.; Xu, G.X.; Shi, Y.X.; Li, Y.; Guo, L.; Han, X.B.; et al. GSTP1 improves CAR-T cell proliferation and cytotoxicity to combat lymphoma. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1665407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dylgjeri, S.; Bartoszek, M.E.; Hrúz, P.; Melhem, H.; Niess, H.J. Cytochrome P450 Cyp2s1 regulation of the intestinal metabolome and microbiome. Mucosal Immunol. 2025. In Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monikh, F.A.; Chupani, L.; Smerkova, K.; Bosker, T.; Cizar, P.; Krzyzanek, V.; Richtera, L.; Franek, R.; Zuskova, E.; Skoupy, R.; et al. Engineered nano selenium supplemented fish diet: Toxicity comparison with ionic selenium and stability against particle dissolution, aggregation and release. Environ. Sci. Nano 2020, 7, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Jiang, L.Q. Research Progress on the Immunomodulatory Effect of Trace Element Selenium and Its Effect on Immune-Related Diseases. Food Ther. Health Care 2020, 2, 86–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, A.J.; McKay, M.D.; Raman, M. Selenium Immunity and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, L.; Qiu, D.J.; Fu, X.; Wu, A.P.; Yang, P.Y.; Yang, Z.G.; Wang, Q.; Yan, L.; Xiao, R. Overexpressing HPGDS in adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells reduces inflammatory state and improves wound healing in type 2 diabetic mice. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, J.M.; Pandeya, A.; Bauer, R.; Christopher, T.; Krug, S.; Honodel, R.; Smita, S.; Warner, L.; Mooney, B.; Gibson, R.A.; et al. Enteric tuft cell inflammasome activation drives NKp46+ILC3 IL22 via PGD2 and inhibits Salmonella. J. Exp. Med. 2025, 222, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.Z.; Wang, Z.T.; Wang, W.L.; Lei, K.K.; Zhou, J.S. Effects of Different Farming Modes on Salmo trutta fario Growth and Intestinal Microbial Community. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumerov, M.V.; Ulrich, E.L.; Zhulin, B.L. MiST 4.0: A new release of the microbial signal transduction database, now with a metagenomic component. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, D1, D647–D653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.M.; Zhao, H.; Wang, X.Y.; Zhang, L.; Mou, C.Y.; Huang, Z.P.; Ke, H.Y.; Duan, Y.L.; Zhou, J.; Li, Q. Effects of different temperatures on Leiocassis longirostris gill structure and intestinal microbial composition. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 7150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, S.; Terova, G.; Ascione, C.; Giannico, R.; Brambilla, F. Next generation sequencing for gut microbiome characterization in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed animal by-product meals as an alternative to fishmeal protein sources. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0193652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.L.; Song, L.; Liu, X.L.; Dong, X.Z. Tepidimicrobium xylanilyticum sp. nov., an anaerobic xylanolytic bacterium, and emended description of the genus Tepidimicrobium. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2009, 59, 2698–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.M.; Ye, Y.L.; Zhong, Y.; Liu, W.K.; Chen, M.L.; Guo, A.L.; Lv, J.; Ma, H.W. Microbial diversity and functional genes of red vinasse acid based on metagenome analysis. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1025886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnedo, M.; Menao, S.; Puisac, B.; Teresa-Rodrigo, T.E.; Gil-Rodríguez, C.M.; López-Viñas, E.; Gómez-Puertas, P.; Casals, N.; Casale, H.C.; Hegardt, G.F.; et al. Characterization of a novel HMG-CoA lyase enzyme with a dual location in endoplasmic reticulum and cytosol. J. Lipid Res. 2012, 53, 2046–2056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, G.X.; Xu, W.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Yin, J.; Kuang, Y.Y. De novo assembly and characterization of the Hucho taimen transcriptome. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 8, 1271–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.H.; Zeng, X.F.; Ren, M.; Mao, X.B.; Qiao, S.Y. Novel metabolic and physiological functions of branched chain amino acids: A review. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holohan, B.C.; Duarte, M.S.; Szabo-Corbacho, M.A.; Cavaleiro, A.J.; Salvador, A.F.; Pereira, M.A.; Ziels, R.M.; Frijters, C.T.M.J.; Pacheco-Ruiz, S.; Carballa, M.; et al. Principles, Advances, and Perspectives of Anaerobic Digestion of Lipids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 49–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Luo, G. Novel Long Chain Fatty Acid (LCFA) Degrading Bacteria and Pathways in Anaerobic Digestion Promoted by Hydrochar as Revealed by Genome-Centric Metatranscriptomics Analysis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2022, 88, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, K.; Qu, H.Y.; Zhou, K.R.; Wang, L.F.; Zhu, C.M.; Chen, H.Q.; Gu, Z.N.; Cui, J.; Fu, G.L.; Li, J.Q.; et al. Distinct Gut Microbiota Induced by Different Fat-to-Sugar-Ratio High-Energy Diets Share Similar Pro-obesity Genetic and Metabolite Profiles in Prediabetic Mice. mSystems 2019, 4, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clements, D.K.; Gleeson, P.V.; Slaytor, M. Short-chain fatty acid metabolism in temperate marine herbivorous fish. J. Comp. Physiol. B-Biochem. Syst. Environ. Physiol. 1994, 164, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rimoldi, S.; Gliozheni, E.; Ascione, C.; Gini, E.; Terova, G. Effect of a specific composition of short- and medium-chain fatty acid 1-Monoglycerides on growth performances and gut microbiota of gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). PeerJ 2018, 6, e5355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angom, S.R.; Nakka, R.M.N. Zebrafish as a Model for Cardiovascular and Metabolic Disease: The Future of Precision Medicine. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.L.; Li, X.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, C.; Liu, Y.; Jin, H.X.; Cao, Y. Effect of the ACAA1 Gene on Preadipocyte Differentiation in Sheep. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 649140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.W.; Lu, C.Y.; Hao, Q.; Zhang, Q.S.; Yang, Y.L.; Olsen, E.R.; Ringø, E.; Ran, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Z.G. Dietary Succinate Impacts the Nutritional Metabolism, Protein Succinylation and Gut Microbiota of Zebrafish. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 894278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, B.B.; Zhou, J.L.; Xia, B.; Li, X.Q.; Wang, R.; Xu, Y.Q.; Li, C.Q. Therapeutic potential of a choline-zinc-vitamin E nutraceutical complex in ameliorating thioacetamide-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver pathology in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.J.; Ye, W.D.; Clements, D.K.; Zan, Z.Y.; Zhao, W.S.; Zou, H.; Wang, G.T.; Wu, S.G. Bacillus licheniformis FA6 Affects Zebrafish Lipid Metabolism through Promoting Acetyl-CoA Synthesis and Inhibiting β-Oxidation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 24, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortés, D.H.; Gómez, A.F.; Marshall, H.S. The Phagosome–Lysosome Fusion Is the Target of a Purified Quillaja saponin Extract (PQSE) in Reducing Infection of Fish Macrophages by the Bacterial Pathogen Piscirickettsia salmonis. Antibiotic 2021, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Xing, X.R.; Wang, H.Y.; Kang, W.; Fan, R.M.; Liu, C.D.; Wang, Y.J.; Wu, W.J.; Wang, Y.B.; Wang, R. SCD1 is the critical signaling hub to mediate metabolic diseases: Mechanism and the development of its inhibitors. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 170, 115586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.X.; Li, B.; Hou, L.J.; Zhou, L.J.; Yang, Q.T.; Zhang, C.F.; Li, H.W.; Zhu, J.; Jia, R. Integrated Metabolomics and Transcriptomics Reveals Metabolic Pathway Changes in Common Carp Muscle Under Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shefer, S.; Erickson, S.K.; Lear, S.R.; Batta, A.K.; Salen, G. Upregulation of hepatic cholesterol 27-hydroxy-lase (CYP27) activity and normal levels of hepatic cholesterol synthesis in cholesterol 7A-hydroxylase (cyp7A1) gene knockout mice. Gastroenterology 2000, 118, A998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Table | Df | SumsOfSqs | MeanSqs | F.Model | R2 | Pr (>F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat1 | 1 | 0.0255 | 0.0255 | 0.3952 | 0.038 | 0.785 |

| Residuals | 10 | 0.6444 | 0.0644 | NA | 0.962 | NA |

| Total | 11 | 0.6699 | NA | NA | 1 | NA |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, M.; Wang, S.; Lin, F.; Han, S.; Zhang, T.; Kuang, Y.; Tong, G. A Hypothesis of Gut–Liver Mediated Heterosis: Multi-Omics Insights into Hybrid Taimen Immunometabolism (Hucho taimen ♀ × Brachymystax lenok ♂). Animals 2026, 16, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010074

Wei M, Wang S, Lin F, Han S, Zhang T, Kuang Y, Tong G. A Hypothesis of Gut–Liver Mediated Heterosis: Multi-Omics Insights into Hybrid Taimen Immunometabolism (Hucho taimen ♀ × Brachymystax lenok ♂). Animals. 2026; 16(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010074

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Mingliang, Shuqi Wang, Feng Lin, Shicheng Han, Tingting Zhang, Youyi Kuang, and Guangxiang Tong. 2026. "A Hypothesis of Gut–Liver Mediated Heterosis: Multi-Omics Insights into Hybrid Taimen Immunometabolism (Hucho taimen ♀ × Brachymystax lenok ♂)" Animals 16, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010074

APA StyleWei, M., Wang, S., Lin, F., Han, S., Zhang, T., Kuang, Y., & Tong, G. (2026). A Hypothesis of Gut–Liver Mediated Heterosis: Multi-Omics Insights into Hybrid Taimen Immunometabolism (Hucho taimen ♀ × Brachymystax lenok ♂). Animals, 16(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010074