1. Introduction

Body weight and size are closely related to the health and production performance of live sows [

1]. With the development of intensive and precise breeding, monitoring livestock body weight and size has become crucial for optimizing production management and assessing animal welfare [

2]. Traditional methods of weighing with a scale and tape measure are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and can cause stress in animals [

3]. Machine vision technology offers intuitive and non-contact measurement advantages [

4]. In recent years, advancements in sensor and artificial intelligence technology have accelerated research on using machine vision to estimate animal body weight and size [

5].

The images obtained by visual sensors can be divided into two-dimensional (2D) images and three-dimensional (3D) images. The technique for determining body weight and size from 2D images is generally to collect 2D RGB images [

6,

7] or grayscale images [

8] of the animal’s back or side, to identify key points of body size measurement through 2D image processing to estimate length, width, and height of body size [

9], and to establish a model to correlate body size with body weight to estimate body weight [

10]. However, 2D images do not include in-depth information and cannot measure 3D body size parameters involving chest circumference, waist circumference, and hip circumference [

11]. At the same time, due to the characteristic of the target being large in the near and small in the far, the image processing process is influenced by the target position and camera perspective [

12]. In addition, the complexity of light, lighting, and background can also affect the results [

13]. For example, when the light is weak or the sow body and the background color are similar, it will make the segmentation of the target and recognition of feature points more difficult [

14].

The 3D images used in current research mainly include depth images and point clouds [

15,

16]. Body size is generally measured through steps such as point cloud segmentation, point cloud 3D reconstruction, feature point recognition of the depth images and point clouds, and point cloud calculation to further estimate body weight [

17]. In some studies, depth images or point clouds of the back of sows can be obtained from a top-view perspective [

18,

19], and body size feature points can be labeled using point cloud calculations based on the anatomical characteristics of the sow’s back [

20,

21]. In order to improve the accuracy of body size point recognition, methods for 3D reconstruction of sow bodies are also commonly used [

22]. Multiple depth cameras were used to capture images of the back and different sides of the sow body [

23]. The sow body and scene were restored through 3D reconstruction, and the background was removed through point cloud segmentation to extract the sow body. After preprocessing processes such as posture normalization, body size feature points were extracted from the reconstructed sow body [

24]. Body size features typically include hip width, hip height, chest width, chest height, body length, chest circumference, abdominal circumference, and hip circumference [

25]. Some studies extract multiple width features of the back for estimating body weight [

26], and the volume of the top view covered by the back depth map is often used as a weight estimation feature [

27,

28]. In order to facilitate the acquisition of features for weight estimation, Nguyen et al. [

29] used the original point cloud as input and extracted 64 potential features using a generative network. Three methods were used to establish models correlating body size features with body weight: Support Vector Regression (SVR), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and AdaBoost. To improve the accuracy of body measure point recognition, Hu et al. [

30] employed a PointNet++ point cloud segmentation model to divide the pig’s body into various parts, including the ears, head, trunk, limbs, and tail. Within these segmented regions, point cloud processing was utilized to pinpoint key body size measurements, achieving a minimum relative error of 2.28%.

In summary, current methods use image or point cloud processing to identify feature points and extract body size traits. Body weight is then estimated through machine learning algorithms. However, these approaches face several major limitations. First, to ensure data consistency and comparability, sows are often required to maintain a uniform posture during image acquisition. This requirement is difficult to achieve in practical settings, reducing the broad applicability of such methods. Second, the processing pipeline involves multiple complex steps, including 3D reconstruction of point clouds, identification of feature points, and calculation of body size measurements. These operations are computationally intensive and time-consuming. The complexity of feature engineering may also introduce errors, affecting the accuracy and stability of feature extraction. Most importantly, relying on hand-crafted features to build machine learning models may constrain both feature representation and the model’s ability to capture complex patterns, ultimately limiting prediction performance.

In recent years, some studies have explored the feasibility of end-to-end body size and weight estimation using automatic feature extraction. Using depth images as input, body weight and size estimation models such as the Xception model [

31], EfficientNets model [

32], and Faster RCNN model [

33] were established. He et al. [

34] preprocessed the point cloud and used distance independent algorithms to map it to 2D grayscale images, establishing a botnet weight estimation model. Both depth and grayscale images are structured data with fixed adjacent positions between them. However, almost all the estimation models used 2D convolution to extract the feature relationship between neighboring positions, thus the extraction accuracy is limited. Point cloud, as an irregular data structure, are able to better characterize 3D space and are therefore a better way to characterize 3D features of sow bodies. Recently, significant advancements have been made in the development of end-to-end algorithms for point cloud segmentation and classification. Extracting features from point clouds is crucial for analyzing 3D scenes. Notably, there are several algorithms that have gained significant attention due to their broad applications and improved results in point cloud classification and segmentation. Some of these algorithms include PointNet++ [

35], DGCNN [

36], KPConv [

37], PointCNN [

38], RandLANet [

39]. Although existing algorithms have made significant progress in enhancing local feature extraction, they often exhibit limitations due to predefined or fixed receptive fields, and primarily perform neighborhood construction and feature aggregation within a single domain. This often results in an inability to fully capture the multifaceted relationships between points, thereby restricting the representational capacity of the features.

To overcome these limitations, this study aims to develop a novel framework for accurate and robust, non-contact estimation of sow body weight and size from 3D point clouds. The specific objectives are as follows:

To establish an effective point cloud segmentation model for extracting the sow‘s back from complex barn backgrounds.

To propose a dual-branch network architecture (DbmoNet) that integrates feature extraction from both Euclidean and feature spaces, enhancing the representation of key geometric features.

To validate the performance of the proposed framework and compare it with existing methods under practical farming conditions.

The overall workflow of this framework follows a four-stage pipeline, as illustrated in

Figure 1: data collection, data preprocessing and dataset construction, point cloud segmentation, and estimation of body weight and size.

The remainder of this paper is organized accordingly:

Section 2 details the data collection and processing pipeline.

Section 3 introduces the methodology, including the KPConv segmentation model and the DbmoNet regression model.

Section 4 presents the experimental results.

Section 5 provides discussion, and

Section 6 concludes the study.

5. Discussion

5.1. Estimation of Body Weight and Size Based on Depth Images

To compare the feature representation capabilities of depth images and point cloud as well as the feature extraction capabilities of 2D and 3D algorithms, the 2D feature extraction algorithm Xception from the literature [

31] was used to build a depth image-based model for the estimation of body weight and size. It was tested in comparison with the performance of the 3D feature extraction model DbmoNet, which was built based on point cloud in this study. The results are shown in

Table 5. The point cloud-based model works better and is lower than the depth image-based model by 0.19%, 0.12%, 0.06%, 0.58%, 0.09%, and 0.04% on MAPE, respectively.

Two-dimensional feature extraction models based on depth images did not perform very well. One aspect of the reason is that the depth image contains background that can interfere with the estimation results. On the other hand, depth images are still structured 2D images with depth values represented by only 256 quantized values with limited feature representation. Point cloud has better representation of 3D features. Therefore, the point cloud was chosen as the basis for the estimation of body weight and size in this study.

5.2. Estimation Results for Different Sow Breeds

The test set of the above model includes all three varieties, and the test results describe the average performance of the mixed samples of the three varieties.

Table 6 shows the average values of the body weight and size and the quantity of three varieties in the test samples. It can be seen that the three varieties have different body shape characteristics. The width CW and HW values of Landrace sows are relatively large, and the length value BL is relatively large. The average body weight BW of Large White sows is smaller, with CW, HW, and BL being smaller than the other two breeds. The body size of cross-breeding is between Landrace and Large White sows.

Separate test sets are established for Landrace, Large White, and Cross-breeding sows, and the test results are shown in

Table 7. It can be seen that the MAPE values between different breeds are at roughly the same level, and the MAPE values of body weight and length of Cross-breeding sows are smaller. This indicates that the model has the best adaptability to cross-breeding sows, its prediction ability of different breeds is similar, and it has good generalization ability.

Compared with the sows in this study, the Landrace, Large White, and Cross-breeding fattening sows have similar body sizes, but the difference is that the average weight of the fattening sows is smaller and the average weight of the sows is larger. Therefore, in order to apply the model in this article to fattening sows, parameter tuning can be performed through transfer learning to estimate the body weight and size of fattening sows. The proposed method for estimating body weight and size through back point cloud and DbmoNet models can also be applied to other farm animals.

In summary, while the three breeds exhibit distinct morphological characteristics, the model maintains comparable estimation accuracy across them. This indicates that the inherent breed variation within the studied population does not substantially degrade the model’s performance, supporting its robustness for application across these common sow breeds.

5.3. Feature Visualization

The interpretable methods for deep learning models currently include Class Activation Maps (CAMs) [

40] and Gradient Weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad CAM) [

41], but these methods cannot be applied to algorithms that directly handle point cloud. In order to enhance the interpretability of point cloud processing algorithms and understand from which points the model learns features, inspired by the idea of pixel gradient weighting in Grad-CAM, a feature visualization method of point cloud Gradient Weighted Point Activation Mapping (PAM) is established. The basic idea of PAM is to obtain 11 feature vector of n original points by taking the maximum value method in the layers of feature extraction before feature compression. The size of the feature value of a point can measure its contribution to the final result. The weight is assigned based on the size of the feature value, and the final n points are assigned different weight values. A heat map is used to represent the size of weights.

For the DbmoNet model, the specific steps to generate PAM are as follows:

Step 1: An n-dimensional feature vector is obtained. In the dual-branch model, the branch based on feature nearest neighbors retains the positional coordinates of n sampled points, while the branch based on location nearest neighbors includes a downsampling process. To obtain the features of n points at different levels, the method of nearest neighbor upsampling is used to align the current layer point cloud to the original points. Then, the features of the two branches are connected to obtain the features of n points at the current layer.

Step 2: Feature compression is performed. The vector is compressed by the maximum value method and the calculation is shown in Equation (19), where

fi is the feature value of the

i-th point,

fij is the

j-th feature value of the

i-th point, max is the maximizing function,

i = 1...

n,

j = 1... 384. The

n × 384 feature vector is compressed to the

n × 1 feature vector.

Step 3: Weights are assigned to points. The features of n points are normalized to generate weights, as shown in Equation (20), where

ωi represents the weight of the

i-th point,

i = 1...

n. Max is the maximum function and min is the minimum function.

Step 4: A heat map is generated. Values are assigned to the RGB components of the n original points of the point cloud based on the weights. According to the weight, the value is assigned in the order of R component, G component, and B component. The larger the weight value, the larger the R component assignment and the smaller the B component assignment. The smaller the weight value, the smaller the R component assignment and the larger the B component assignment.

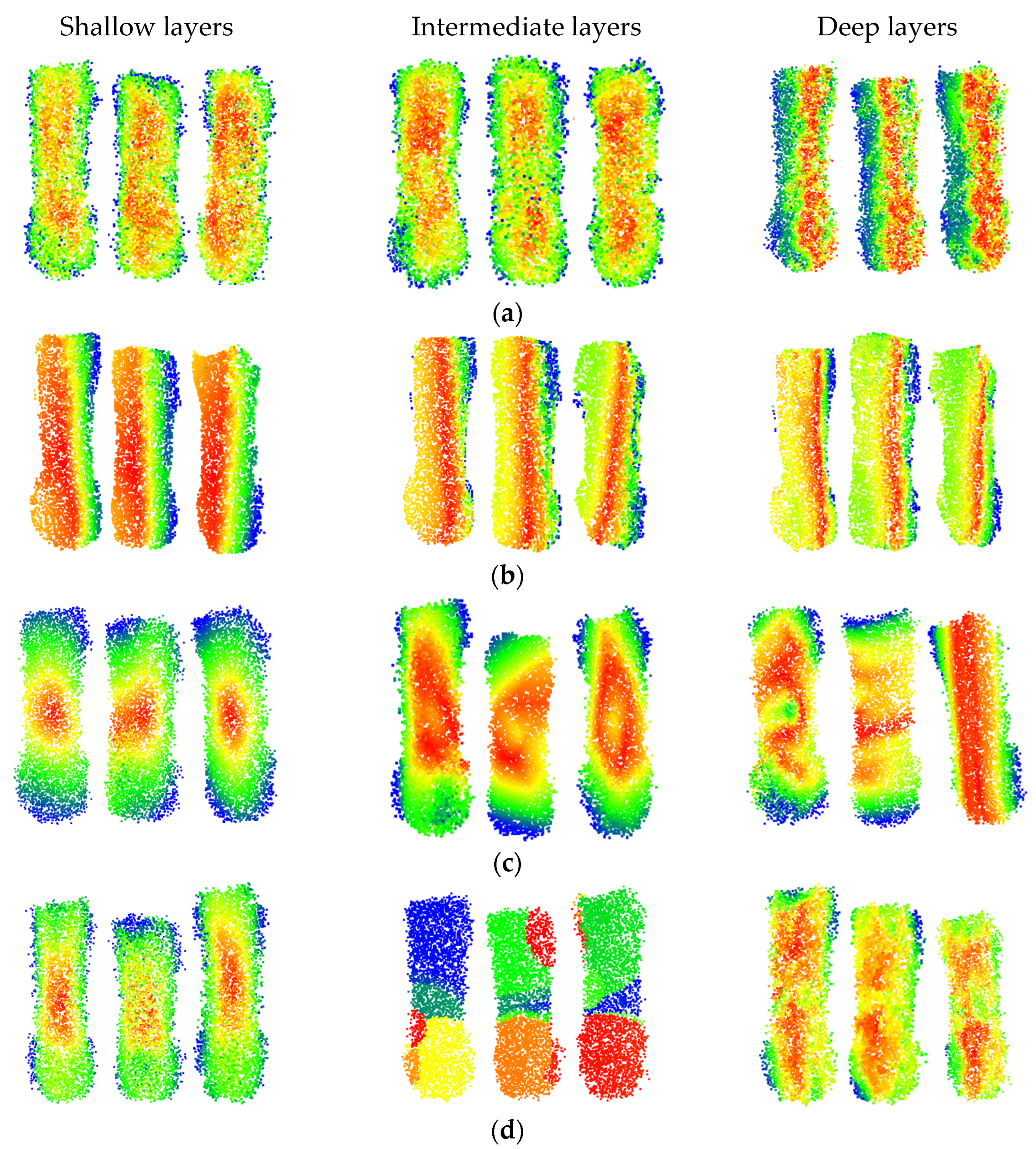

The PAM maps of partial samples at different depths for various models are shown in

Figure 11. The red points represent the maximum activation level, the blue points represent the activation level, and points of other colors have intermediate activation levels. The PAM maps of different models at various layers provide a better understanding of the process of feature learning.

It can be observed that the DbmoNet model predominantly learns features of adjacent points in the central region of the body at shallow and intermediate layers, while it learns features of the spine region and one side of the body at deeper layers. From the biological characteristics of sows, points on the spine belong to positions with similar features and adjacent positions, including the length and height characteristics of the sow’s body. One side of the sow body is the nearby points in the position. Due to the roughly symmetrical shape of the sow’s body, width features can be derived from the point cloud on one side. Therefore, there is no need to learn additional body features on the other side, which is more conducive to the rapid convergence of the model.

This effective learning pattern arises from the dual-branch design of DbmoNet. The location-based branch captures stable spatial structures, such as the linear spine and body-side contour, which are fundamental for estimating length, height, and width. Concurrently, the feature-based branch groups points with similar characteristics (e.g., along the curved spine), enabling the model to sensitively perceive continuous shape variations. This complementary mechanism allows the model to fully leverage the body’s approximate symmetry—learning the spine and one side thoroughly provides sufficient information to characterize the entire back accurately and efficiently.

The DGCNN model primarily learns features from points that are similar in nature, and as the depth increases, the learned features gradually tend towards the length direction of the body. Features learned by the KPConv model tend to cover the entire sow’s body as the depth increases, aligning with its principle of continuously extracting features from a larger range of points through point convolution. In contrast, the PointNet++ model learns features of the central region of the sow’s body at shallow layers, gradually extending to features of different areas such as the buttocks, waist, and chest as the model deepens. At deeper levels, the model focuses on features of the central area between the chest and buttocks. Thus, the features learned by the DbmoNet model are more conducive to reflecting the dimensions of the subject, such as length, width, and height.

5.4. Comparison to Previous Works

Typical methods of estimating body weight body size in recent years were compared and the results are shown in

Table 8.

Compared to previous work, this study has the following advantages:

Firstly, the DbmoNet can achieve simultaneous prediction of body weight and size, including six dimensions: BW, CW, HW, BL, CH, and HH. The training of multi-regression models is more complex than that of single regression models. The Loss value of a multi-regression model needs to be fed back to adjust each of the multiple outputs, thus training the shared network weights. In this study the Loss value is set to the sum of the six output dimensions of MSE, which improves the sensitivity of feedback. Currently, in most research, only body size estimation is generally achieved [

11,

15,

17,

22,

23,

30,

36,

40], or only body weight estimation is achieved [

32,

33,

34], or body size is estimated first and then body weight is estimated based on body size [

8,

26,

27,

28,

29].

Secondly, the back point cloud-based method for body weight and body size estimation is not affected by environmental light as compared to the 2D image-based method. The accuracy of the estimation is higher in the point cloud-based method compared to the 3D depth image-based methods. From

Figure 2, it can be seen that the sample contains samples under strong and weak light conditions. Even for samples like

Figure 2c that cannot be distinguished by the naked eye in RGB images, the integrity of the point cloud is basically not affected. However, the volume measurement estimation method based on 2D RGB images requires image recognition of volume measurement feature points within the visible light range of the naked eye [

6]. The MAE values of methods in different studies in

Table 8 are not directly comparable due to different experimental samples in different studies. The previous comparison experiments in this study show that the point cloud-based body weight and size estimation model performs better than the depth image-based estimation model.

Thirdly, the method proposed in this study does not involve complex image processing and point cloud processing, and the segmentation of point cloud and the estimation of body weight and size are end-to-end, avoiding the gradual and complex segmentation process of fences, ground, and sow heads and tails in most current studies [

8,

28]. At the same time, it also avoids the complex process of volumetric feature recognition [

27,

28,

30]. Other methods for estimating body weight and size through deep learning models require preprocessing processes such as resizing [

31], cropping [

32], and complex point cloud denoising and smoothing [

34]. In contrast to the experiment of He et al. [

34], the samples in this study were more complete, containing 60 sows of three breeds. Meanwhile, although the initial data collected in the study of He et al. [

34] was also point cloud, it was processed as a 2D grayscale image as input to the body weight estimation model, and a 2D convolutional algorithm was used. In contrast, the algorithm used in this study is 3D, which directly processes the point cloud to better preserve the 3D visual features of the sow body.

The subjects of this study are sows in confinement pens, with each image containing only a single animal and no overlap between individuals. Consequently, the direct applicability of this method to free-range conditions with multiple animals is limited and was not evaluated. Acknowledging the sample size of 60 sows, two key considerations arise regarding the model’s wider application. First, for sows, the model’s performance may decline for individuals with body shapes that fall far outside the range captured in our current dataset as its learned features are optimized for the predominant morphology in the study. More fundamentally, the DbmoNet architecture and its effectiveness are intrinsically linked to the specific geometric characteristics of the porcine back. Therefore, direct application to other livestock species with fundamentally different torso topologies and contours is not straightforward and would likely require significant architectural adaptation and retraining. Thus, while this study establishes a robust, non-contact framework for sow body measurement, future work is needed to explicitly test its limits across a wider sow population and to explore transfer learning strategies for adapting the approach to other species.

The automated, non-contact monitoring system presented in this study is expected to generate significant economic benefits for intensive sow production. First, by replacing manual weighing and measuring, it substantially reduces labor costs and minimizes stress-induced productivity losses. Second, the continuous, high-frequency data on body weight and size enable precise feeding strategies and early detection of health issues, potentially improving feed conversion efficiency and reducing veterinary costs. Overall, this technology provides a tool for data-driven management decisions that can enhance both the economic sustainability and animal welfare standards of modern pig farms.