iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals the Potential Mechanisms Underlying Diet Supplementation with Stevia Isochlorogenic Acid That Alleviates Immunosuppression in Cyclophosphamide-Treated Broilers

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SICA, Animals, and Dietary Treatments

2.2. Animal Groups and Sample Collection

2.3. Determination of Immune Organ Indices

2.4. Determination of Histological Examination

2.5. Determination of Serum Biochemistry

2.6. Preparation of Protein and Peptide Samples for iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Analysis

2.7. DIA Mass Spectrometry Detection

2.8. Protein Identification and Bioinformatics Analysis

2.9. Quantitative PCR Analysis

2.10. Molecular Docking Analysis

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

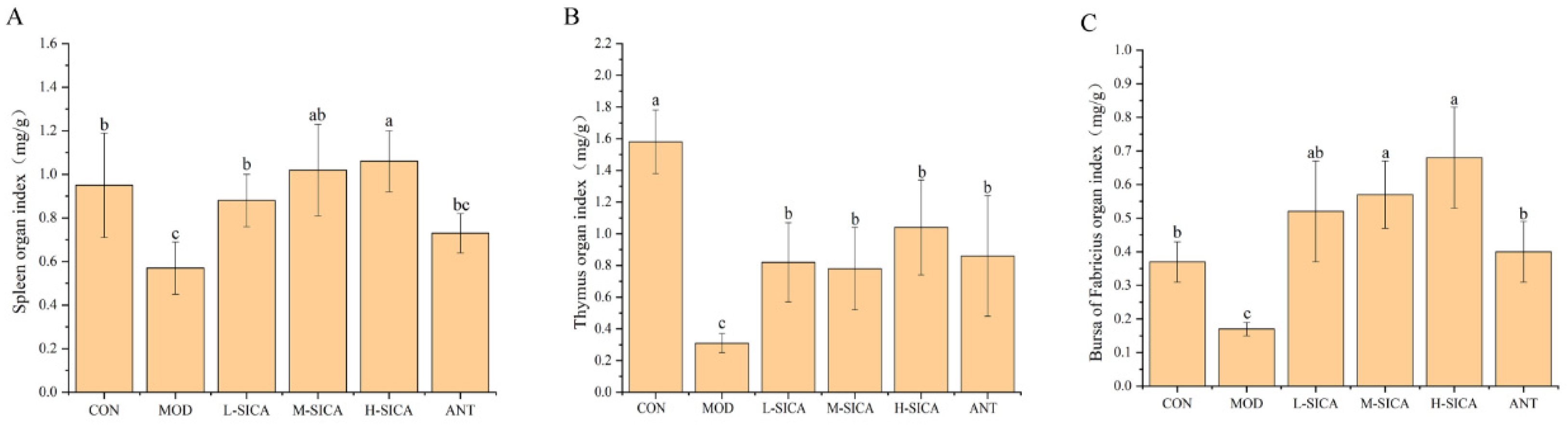

3.1. Effect of SICA on the Immune Organ Indices

3.2. Effect of SICA on the Spleen Histological Examination

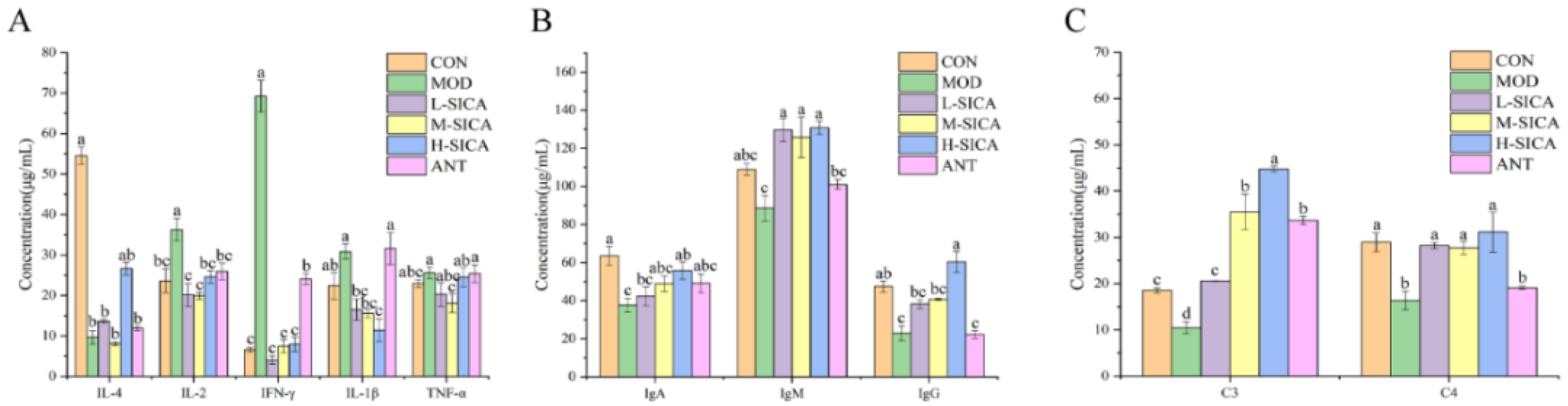

3.3. Effect of SICA on the Serum Biochemistry

3.4. Identification of Protein by iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Analysis

3.5. Identification of DEPs

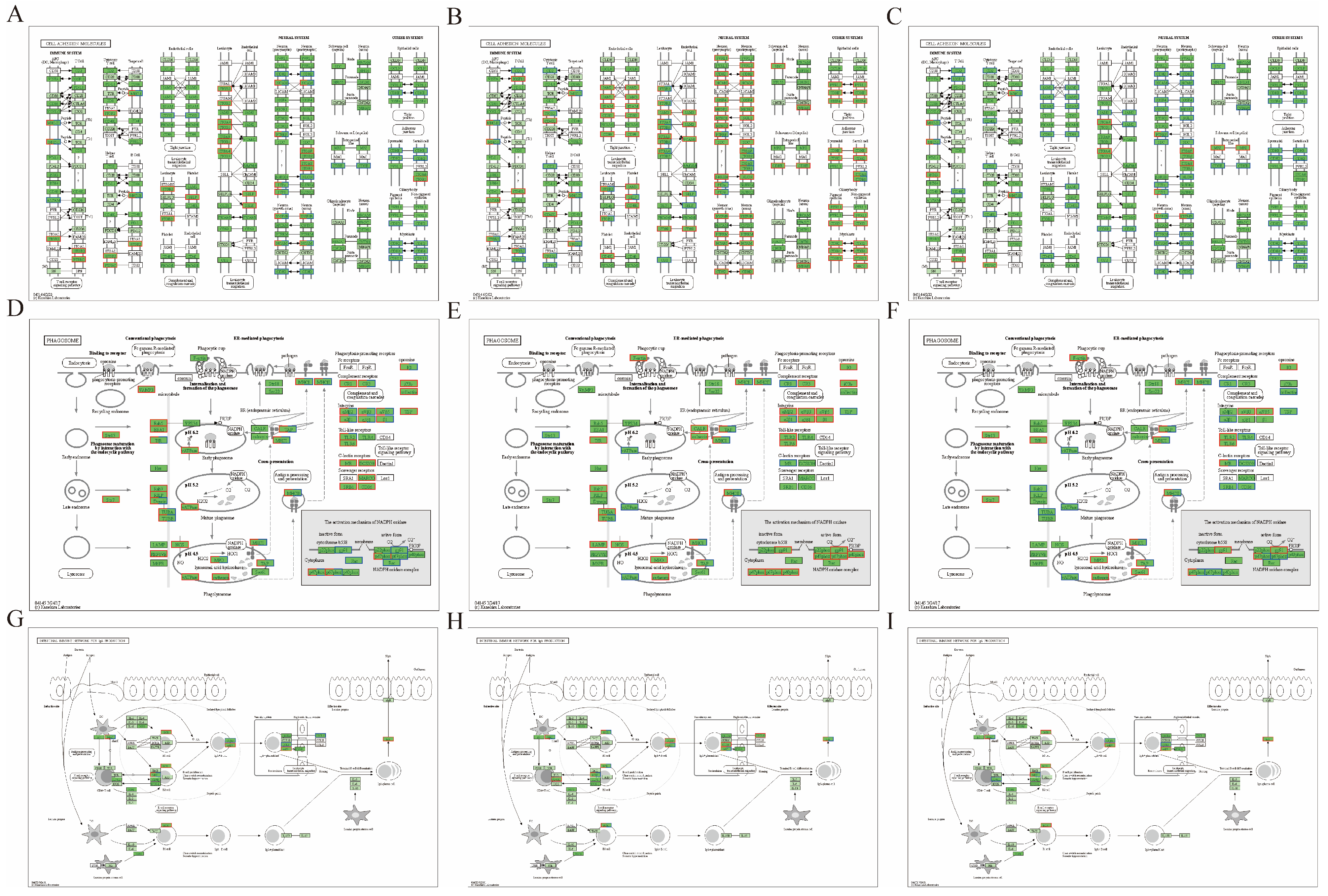

3.6. GO Enrichment Classification of DEPs

3.7. KEGG Enrichment Classification of DEPs

3.8. Selection of DEPs

3.9. Effect of SICA on mRNA Expression of DEPs

3.10. Molecular Docking Studies of SICA and DEPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hashim, M.S.; Yusop, S.M.; Rahman, I.A. The impact of gamma irradiation on the quality of meat and poultry: A review on its immediate and storage effects. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Production Quantities of Meat of Chickens, Fresh or Chilled by Country. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (accessed on 19 October 2025).

- Guerrini, A.; Zago, M.; Avallone, G.; Brigandì, E.; Tedesco, D.E.A. A field study on Citrus aurantium L. var. dulcis peel essential oil and Yucca schidigera saponins efficacy on broiler chickens health and growth performance during coccidiosis infection in rural free-range breeding system. Livest. Sci. 2024, 282, 105437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.W.; Wang, Y.Z.; Zhao, X.H. Research on the drug resistance mechanism of foodborne pathogens. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 162, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.P.; Liu, Z.M.; Liang, Z.Y.; Zhu, C.L.; Li, D.Y.; Kong, Q.; Mou, H.J. Development strategies and application of antimicrobial peptides as future alternatives to in-feed antibiotics. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 927, 172150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.L.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, J.X.; Han, S.W.; Liu, X.C.; Yuan, C.Y.; Ndayisenga, F.; Shi, J.P.; Zhang, B.G. Optimized strategy valorizing unautoclaved cottonseed hull as ruminant alternative feeds via solid-state fermentation: Detoxifying polyphenols, restraining hazardous microflora and antibiotic-resistance gene hosts. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 28, 102937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, K.; Zhang, K.; Gao, W.; Bai, S.; Wang, J.; Song, W.; Zeng, Q.; Peng, H.; Lv, L.; Xuan, Y.; et al. Effects of stevia extract on production performance, serum biochemistry, antioxidant capacity, and gut health of laying hens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, M.; Naveen, P.; Pal, P.K. Agronomical and biotechnological strategies for modulating biosynthesis of steviol glycosides of Stevia rebaudiana Bertoni. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aromat. Plants 2024, 43, 100580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.W.; Li, X.M.; Zhang, K.; Lv, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, P.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, J. Integrated multi-omics reveals the beneficial role of chlorogenic acid in improving the growth performance and immune function of immunologically stressed broilers. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 14, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.B.; Ji, Y.R.; Miao, Z.G.; Lv, H.Y.; Lv, Z.P.; Guo, Y.M.; Nie, W. Effects of baicalin and chlorogenic acid on growth performance, slaughter performance, antioxidant capacity, immune function and intestinal health of broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.Q.; Zhen, W.R.; Bai, D.Y.; Liu, K.; He, X.; Ito, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; et al. Effects of dietary chlorogenic acid on intestinal barrier function and the inflammatory response in broilers during lipopolysaccharide-induced immune stress. Poult. Sci. 2023, 102, 102623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.Y.; Jiang, H.T.; Wang, Y.J.; Yan, A.; Liu, G.; Liu, S.; Chen, B. Dietary supplementation with isochlorogenic acid improves growth performance and intestinal health of broilers. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 21, 472–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateya, A.I.; Arafat, N.; Saleh, R.M.; Ghanem, H.M.; Naguib, D.; Radwan, H.A.; Elseady, Y.Y. Intestinal gene expressions in broiler chickens infected with Escherichia coli and dietary supplemented with probiotic, acidifier and synbiotic. Vet. Res. Commun. 2019, 43, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegazy, A.M.E.; Morsy, A.M.; Salem, H.M.; Al-Zaban, M.I.; Alkahtani, A.M.; Alshammari, N.M.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Altarjami, L.R.; Bahshwan, S.M.A.; Al-Qurashi, M.M.; et al. The therapeutic efficacy of neem (Azadirecta indica) leaf extract against coinfection with Chlamydophila psittaci and low pathogenic avian influenza virus H9N2 in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, C.L.; Miao, F.J. Immunomodulatory and antioxidant effects of hydroxytyrosol in cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppressed broilers. Poult. Sci. 2022, 101, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Sultana, N.; Haque, Z.; Rafiqul Islam, M. Effect of dietary dexamethasone on the morphologic and morphometric adaptations in the lymphoid organs and mortality rate in broilers. Vet. Med. Sci. 2023, 9, 1656–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathi, M.; Saeidian, S.; Baghaeifar, Z.; Varzandeh, S. Chitosan oligosaccharides in the diet of broiler chickens under cold stress had anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effects and improved hematological and biochemical indices, cardiac index, and growth performance. Livest. Sci. 2023, 276, 105338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.X.; Lin, S.Q.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.Z.; Liu, Y.X.; Wang, K.K.; Zhu, T.Y.; Li, G.M.; Yin, B.; Wan, R.Z. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomic analysis reveals the toxic mechanism of diclofenac sodium on the kidney of broiler chicken. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 249, 109129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.S.; Zheng, H.J.; Yan, R.; Lang, L.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, B.; Zhang, D.Y.; Lin, H.S.; Jia, Y.X.; Pan, S.Y.; et al. Vinculin identified as a potential biomarker in hand-arm vibration syndrome based on iTRAQ and LC–MS/MS-based proteomic analysis. J. Proteome Res. 2023, 22, 2714–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, D.; Lei, A.T.; Nie, C.C.; Chen, Y. The protective effect of Ganoderma atrum polysaccharide on intestinal barrier function damage induced by acrylamide in mice through TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB based on the iTRAQ analysis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 171, 113548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.M.; Gao, P.; Zhao, J.H.; Wang, G.D.; Zhang, H.M.; Cao, W.L.; Xue, X.; Zhang, Y.F.; Ma, Y.; Hua, R.; et al. iTRAQ-based quantitative proteomics analysis of defense responses triggered by the pathogen Rhizoctonia solani infection in rice. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 139–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Q.; Liu, T.G.; Bai, C.; Ma, X.Y.; Liu, H.; Zheng, Z.A.; Wan, Y.X.; Yu, H.; Ma, Y.L.; Gu, X.H. iTRAQ-based proteomics reveals the mechanism of action of Yinlai decoction in treating pneumonia in mice consuming a high-calorie diet. J. Tradit. Chin. Med. Sci. 2024, 11, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzy, A.; Giel, A.S.; Fenske, L.; Bach, A.; Herden, C.; Engel, K.; Heuser, E.; Boelhauve, M.; Ulrich, R.G.; Vogel, K.; et al. Development and validation of a triplex real-time qPCR for sensitive detection and quantification of major rat bite fever pathogen Streptobacillus moniliformis. J. Microbiol. Methods 2022, 199, 106525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesvadbova, M.; Dziedzinska, R.; Hulankova, R.; Babak, V.; Kralik, P. Quantification of the percentage proportion of individual animal species in meat products by multiplex qPCR and digital PCR. Food Control 2023, 154, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.X.; Yan, H.J.; Feng, Y.; Cui, L.; Hussain, H.; Park, J.H.; Kwon, S.W.; Xie, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Characterization of the structure, anti-inflammatory activity and molecular docking of a neutral polysaccharide separated from American ginseng berries. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 174, 116521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.J. Analysis of environmental pollutant bisphenol F elicited prostate injury targets and underlying mechanisms through network toxicology, molecular docking, and multi-level bioinformatics data integration. Toxicology 2024, 506, 153847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; Banerjee, A.; Manna, K.; Sarkar, D.; Shil, A.; Sikdar Ne E Bhakta, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Maji, B.K. Quercetin counteracts monosodium glutamate to mitigate immunosuppression in the thymus and spleen via redox-guided cellular signaling. Phytomedicine 2024, 126, 155226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.R.; Liu, X.B.; Lv, H.Y.; Guo, Y.M.; Nie, W. Effects of Lonicerae flos and Turmeric extracts on growth performance and intestinal health of yellow-feathered broilers. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 103488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Sun, W.J.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, J.W.; Jia, X.T.; Guo, X.Q.; Zhao, Q.Y.; Tang, C.H.; Yin, J.D.; Zhang, J.M. Selenium deficiency induces spleen pathological changes in pigs by decreasing selenoprotein expression, evoking oxidative stress, and activating inflammation and apoptosis. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2021, 12, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.X.; Li, X.Q.; Bello, B.K.; Zhang, T.M.; Yang, H.T.; Wang, K.; Dong, J.Q. Difenoconazole causes spleen tissue damage and immune dysfunction of carp through oxidative stress and apoptosis. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 237, 113563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.H.; Wang, J.M.; Li, B.Y.; Gong, M.Z.; Cao, C.; Song, L.L.; Qin, L.Y.; Wang, Y.M.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Li, Y.M. Chlorogenic acid, rutin, and quercetin from Lysimachia christinae alleviate triptolide-induced multi-organ injury in vivo by modulating immunity and AKT/mTOR signal pathway to inhibit ferroptosis and apoptosis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2023, 467, 116479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.H.; Ge, S.; Xiao, P.; Liu, Y.L.; Yu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sun, L.P.; Yang, L.; Wang, D.Q. UV-stimulated riboflavin exerts immunosuppressive effects in BALB/c mice and human PBMCs. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 173, 116278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herwig, E.; Classen, H.L.; Schwean-Lardner, K.V. Assessing the effect of rate and extent of starch digestion in broiler and laying hen feeding behaviour. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2019, 211, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, G.J.; Liu, S.Y.; Zhu, R.; Li, D.L.; Meng, S.T.; Wang, Y.T.; Wu, L.F. Chlorogenic acid improves common carp (Cyprinus carpio) liver and intestinal health through Keap-1/Nrf2 and NF-κB signaling pathways: Growth performance, immune response and antioxidant capacity. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 146, 109378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.W.; Zhang, L.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.Y.; Luan, X.Q.; Xia, X.L.; Gu, W.; Du, J.; Bi, K.R.; Wang, L.; et al. Proteome and gut microbiota analysis of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) in response to Hepatospora eriocheir infection. Aquaculture 2024, 582, 740572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, F.Y.; Zhai, W.Y.; Yin, Y.; Peng, C.; Ning, C.Q. Advanced protein adsorption properties of a novel silicate-based bioceramic: A proteomic analysis. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.L.; Meng, J.Y.; Zhou, J.Y.; Zhang, J.S.; Zhang, C.Y. Integrated transcriptomic and proteomic analyses reveal the molecular mechanism underlying the thermotolerant response of Spodoptera frugiperda. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, H.; Wang, J.H.; Ma, L.L.; Li, S.G.; Wang, J.Q.; Geng, F. Applied Research Note: Proteomic analysis reveals potential immunomodulatory effects of egg white glycopeptides on macrophages. J. Appl. Poult. Res. 2024, 33, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xiao, J.; Wu, S.H.; Liu, L.; Zeng, X.M.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Z.W. Clinical application of serum-based proteomics technology in human tumor research. Anal. Biochem. 2023, 663, 115031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.L.; Zhao, X.L.; Hu, Z.Y.; Liu, J.; Ma, J.; Fan, Y.L.; Liu, D.H. iTRAQ-based proteomics identifies proteins associated with betaine accumulation in Lycium barbarum L. J. Proteom. 2024, 290, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.T.; Wang, S.F.; Tao, F.Q.; Ma, X.M.; Zhang, J.; Li, G.F.; Li, M.Z.; Huang, Y.L. Immunomodulation of thymus by Cistanche deserticola polysaccharides analyzed via transcription-associated proteomic techniques. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauser, J.T.; Lindner, R. Coalescence of B cell receptor and invariant chain MHC II in a raft-like membrane domain. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2014, 96, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Lital, N.A.; Henriette, M.; Elizabeth, D.M. Synergy between B cell receptor/antigen uptake and MHCII peptide editing relies on HLA-DO tuning. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Shi, Y.; Liu, R.; Song, K.C.; Chen, L. Structure of human phagocyte NADPH oxidase in the activated state. Nature 2024, 627, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahan, M.I.; Antony, S.; Juhasz, A.; Jiang, G.; Konate, M.; Lu, J.; Meitzler, J.; Wu, Y.; Roy, K.; Doroshow, J.H. Abstract 876: CD40-induced growth inhibition of Burkitt lymphoma: A possible role for NADPH oxidase by upregulation of p67phox. Cancer Res. 2019, 79, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Zou, Z.; Li, J.; Shen, Q.; Liu, L.; An, X.; Yang, S.; Xing, D. Photoactivation of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated Src and protein kinase C pathway enhances MHC class II-restricted T cell immunity to tumours. Cancer Lett. 2021, 523, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, M.; Lal, G. The Regulatory Function of CCR9+ Dendritic Cells in Inflammation and Autoimmunity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 536326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deh Sheikh, A.A.; Akatsu, C.; Abdu-Allah, H.H.M.; Suganuma, Y.; Imamura, A.; Ando, H.; Takematsu, H.; Ishida, H.; Tsubata, T. The Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase SHP-1 (PTPN6) but Not CD45 (PTPRC) Is Essential for the Ligand-Mediated Regulation of CD22 in BCR-Ligated B Cells. J. Immunol. 2021, 206, 2544–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agace, W. Tissue-tropic effector T cells: Generation and targeting opportunities. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2006, 6, 682–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehara, Y.; Miyano, K.; Yuzawa, S.; Akimoto, R.; Takeya, R.; Sumimoto, H. A conserved region between the TPR and activation domains of p67phox participates in activation of the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 31435–31445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, C.; Marcotte, E.M. Insights into the regulation of protein abundance from proteomic and transcriptomic analyses. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2012, 13, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasir, M.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Z.; Luo, M.; Wang, G. NAD(P)H-dependent thioredoxin-disulfide reductase TrxR is essential for tellurite and selenite reduction and resistance in Bacillus sp. Y3. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Dong, Y.L.; Wang, G.R.; Huang, Z.S.; Song, W.T.; Zheng, X.Y.; Zhang, P.; Yao, M.J. Exploring the pharmacological mechanism of Tongluo Qingnao formula in treating acute ischemic stroke: A combined approach of network pharmacology, molecular docking and experimental evidences. Pharmacol. Res. Mod. Chin. Med. 2024, 13, 100550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Component | Content (g/kg) | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Period | Growth Period | |

| Corn (7.5% CP) | 508.7 | 506.7 |

| Soybean meal (44% CP) | 346.5 | 338.7 |

| Corn gluten meal (60% CP) | 50.0 | 50.0 |

| Cottonseed bioactive peptides (46% CP) | 0.0 | 6.0 |

| Wheat bran (14.8% CP) | 20.3 | 22.6 |

| Soybean oil | 26.7 | 26.7 |

| DL-methionine | 2.8 | 2.8 |

| L-lysine | 4.0 | 4.0 |

| L-threonine | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| Choline chloride | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Monocalcium phosphate (15% Ca, 22.5% P) | 15.5 | 15.3 |

| Calcium carbonate | 16.5 | 16.0 |

| Sodium chloride | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Sodium bicarbonate | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Premix | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Calculated composition | ||

| Metabolizable energy, kcal/kg | 3000.0 | 3000.0 |

| Crude protein | 230.0 | 233.0 |

| Lysine | 14.4 | 14.4 |

| Methionine | 6.95 | 6.94 |

| Threonine | 9.70 | 9.70 |

| Tryptophan | 2.50 | 2.50 |

| Arginine | 14.9 | 15.0 |

| Isoleucine | 11.4 | 11.2 |

| Leucine | 21.7 | 21.5 |

| Ca | 9.6 | 9.6 |

| Available P | 4.8 | 4.8 |

| Gene Name | Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Amplicon Length (bp) | Temperature | GenBank Accession Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward | CCGTCCTCTCTGGCAAAGTC | 90 | 60.39 | ENSGALT00010053593.1 |

| Reverse | CCCTTGAAGTGTCCGTGTGT | 60.18 | |||

| BCR | Forward | CCAGTGGCAAGCTGAAGGTA | 109 | 59.96 | ENSGALT00010064499.1 |

| Reverse | CGCAGTGGTGCATTTGTTCA | 59.97 | |||

| CCR9 | Forward | GCACAGTGGGAAATGCCTTG | 281 | 60.04 | ENSGALT00010042152.1 |

| Reverse | TCCGCCTTTGCTTGGAAGAT | 59.96 | |||

| BLB2 | Forward | CGGCGTTCTTCTTCTACGGT | 58 | 60.11 | ENSGALT00010007045.1 |

| Reverse | CCTGTCCAGAAACCTCACCC | 59.96 | |||

| PTPRC | Forward | TCCTTCTCAAACTCCGACGC | 60 | 60.04 | ENSGALT00010029609.1 |

| Reverse | CCAGCACTGCAATGAACCAC | 60.04 | |||

| NCF2 | Forward | TGTTGTGTGAAACGGTTGGG | 249 | 59.19 | XM_040677543.2 |

| Reverse | GCTAGAAAGCAAGCTTAGCAGA | 58.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jin, J.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Q. iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals the Potential Mechanisms Underlying Diet Supplementation with Stevia Isochlorogenic Acid That Alleviates Immunosuppression in Cyclophosphamide-Treated Broilers. Animals 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010025

Jin J, Zhao S, Zhao P, Zhang Y, Wu L, Zhou L, Sun Y, Zhao W, Zhou Q. iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals the Potential Mechanisms Underlying Diet Supplementation with Stevia Isochlorogenic Acid That Alleviates Immunosuppression in Cyclophosphamide-Treated Broilers. Animals. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Jiatong, Shuqi Zhao, Pengyu Zhao, Yushuo Zhang, Lifei Wu, Liangfu Zhou, Yasai Sun, Wen Zhao, and Qian Zhou. 2026. "iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals the Potential Mechanisms Underlying Diet Supplementation with Stevia Isochlorogenic Acid That Alleviates Immunosuppression in Cyclophosphamide-Treated Broilers" Animals 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010025

APA StyleJin, J., Zhao, S., Zhao, P., Zhang, Y., Wu, L., Zhou, L., Sun, Y., Zhao, W., & Zhou, Q. (2026). iTRAQ-Based Proteomics Reveals the Potential Mechanisms Underlying Diet Supplementation with Stevia Isochlorogenic Acid That Alleviates Immunosuppression in Cyclophosphamide-Treated Broilers. Animals, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010025