1. Introduction

Early-weaned piglets exhibit a high capacity for rapid growth and protein deposition, and therefore have high protein requirements. Protein, as a core nutrient for building body tissues and maintaining metabolic activities, directly affects a piglet’s growth performance [

1,

2]. Lower protein levels in diets reduced gastrointestinal burden and decreased harmful bacterial proliferation caused by undigested protein, thereby improving intestinal microecological balance [

3]. However, protein levels that are too low may not meet the needs of piglets with high growth potential, limiting their growth rate [

4]. On the other hand, previous studies suggested that diets containing approximately 22–24% CP may enhance Average Daily Gain (ADG) and Average Daily Feed Intake (ADFI) in early-weaned piglets when dietary amino acid balance and energy density were optimized [

5]. However, this effect may vary with breed, sex, weaning age, weight, or amino acid profile. In addition, high protein intake may cause undigested protein to remain in the gastrointestinal tract, increasing ammonia emissions and intestinal health risks [

6,

7]. Based on this, it is essential to verify the extent of compensatory growth and protein deposition, specifically alongside the interaction with antibiotic withdrawal, when feeding piglets a diet with a protein level of 19% during the subsequent rearing phase.

Due to physiological immaturity, such as low disease resistance and underdeveloped digestive tracts, post-weaned piglets often experience ‘early weaning syndrome’ [

8]. This syndrome is characterized by poor appetite, slow growth, diarrhea, and increased mortality [

9]. To mitigate these issues, the swine industry has traditionally used in-feed antibiotics to reduce pathogenic bacterial load and prevent post-weaning diarrhea, thereby indirectly improving nutrient utilization and allowing for piglets to realize their growth potential [

10]. However, the overuse of antibiotics can spread antibiotic-resistant bacteria and disrupt the intestinal microecology, posing threats to public health [

11,

12]. Consequently, there is a global regulatory trend toward restricting or banning antibiotic growth promoters. While total prohibition is the ultimate goal, immediate withdrawal without effective alternatives often leads to significant declines in performance and increased mortality rates [

13]. To address this transition, a strategic reduction approach may be necessary. Therefore, the present study applied antibiotics strictly during the highly vulnerable S1 phase, then discontinued their use during the S2 phase. This design allows for investigation into the effects of this phased strategy on growth performance, body composition, and gut health in piglets.

The aim of this study is to investigate how early dietary protein restriction (18% and 24% CP) during the S1 phase, followed by restoration to 19% CP in the S2 phase, induces compensatory growth and enhances protein deposition efficiency without impairing intestinal integrity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals and Experimental Design

One hundred weaned piglets (21 days of age; 6.39 ± 0.03 kg BW; Duroc × Landrace × Yorkshire) were randomly assigned to 4 treatments: 18% CP antibiotic-free group, 18% CP with antibiotics group, 24% CP antibiotic-free group, 24% CP with antibiotics group with 5 animals per pen and 5 pens (3 pens with 3 barrows and 2 gilts, 2 pens with 2 barrows and 3 gilts) per group. The added antibiotics were 30 mg/kg bacitracin methylene disalicylate, 75 mg/kg chlortetracycline, and 300 mg/kg calcium oxytetracycline. During the restriction phase, the weaned piglets in different treatment groups were fed their respective experimental diets. Subsequently, from day 15 post-weaning until reaching 25 kg, all piglets were fed the same antibiotic-free diet (19% CP) until their average BW reached the average target BW of 25 ± 0.15 kg. The schematic diagram for the experimental design is shown in

Figure 1. Experimental diets were formulated as pelleted feeds for piglets from 0 to 14 days post-weaning and from 15 days to 25 kg BW, based on a corn-soybean meal diet and formulated with reference to the NRC (2012) [

14] nutrient requirements for 7–11 kg and 11–25 kg pigs. Ingredient composition and nutrient composition of the diets are presented in

Table 1.

Piglets were housed in a nursery facility (2.20 × 1.50 m2), which had a hard plastic fully slatted floor, a multi-hole stainless feeder, and a single bowl drinker. Pigs had free access to feed and water throughout the experiment period.

2.2. Sample Collection

On day 0, day 14, and when the piglets reached approximately 25 kg, each piglet was weighed individually after a 12 h fast. The feed consumption of the piglets was recorded, and the Average Daily Gain (ADG), Average Daily Feed Intake (ADFI), and Gain-to-Feed (G:F) ratio were calculated for days 0–14 and from day 15 until the piglets reached 25 kg. On day 14 of the experiment, and when the piglets reached a BW of 25 kg, 10 mL of blood was collected from one piglet per pen (with BW close to the group average) via the anterior vena cava. The samples were centrifuged at 3500 r/min for 10 min to separate the serum, which was then transferred into sterile centrifuge tubes, labeled, and stored at −80 °C for later use. Fresh feces from each pen of piglets were collected for three consecutive days during the S1 phase (6–8 days post-weaning) and the S2 phase (27–29 days post-weaning) using the partial fecal collection method [

15]. The samples were weighed, and for every 100 g of sample, 10 mL of 10% sulfuric acid was added and thoroughly mixed for nitrogen fixation. The treated samples were then stored at −20 °C for later use. On the 14th day after the start of the trial, 5 piglets were randomly selected from each group (two barrows and three gilts per treatment). After anesthesia with sodium pentobarbital, the piglets were slaughtered. The abdominal cavity was opened, and the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine were quickly ligated. The pH of the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and colon contents was immediately measured using a portable pH meter (HI 9024C, HANNA Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA), with three repeated measurements taken and the average value recorded. The middle segment of the colon contents was collected in a sterile centrifuge tube and quickly frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80 °C for later use. Approximately 2 cm of the middle duodenum, jejunum, and distal ileum were taken, gently flushed with pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline solution to remove contents, and then placed in 4% paraformaldehyde sample tubes for preservation.

Additionally, before the start of the experiment, five pigs (three barrows and two gilts) were selected as the initial slaughter group to measure baseline body composition. On day 14 of the experiment, and when the piglets reached 25 kg, following a 12 h fast and individual weighing, five piglets per group (three barrows and two gilts per treatment at each phase) with BW close to the group average were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital and slaughtered by exsanguination, with all blood carefully collected from each piglet. The slaughter followed the procedure outlined by Hou et al. [

16] and Jones et al. [

17].

2.3. Serum Biochemical Parameter Measurement

Serum total protein, albumin, blood urea nitrogen, glucose, triglycerides, total cholesterol, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and creatinine levels were determined using an automated biochemical analyzer (Selectra Pro XL, Vital Scientific, Woerden, The Netherlands) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All reagent kits were purchased from Sinopharm Beijing Bio-Technology Co., Ltd, located in Beijing, China.

2.4. Serum Free-Amino-Acid Concentration Determination

Briefly, 0.4 mL of the serum sample was accurately pipetted into a sterile centrifuge tube. Then, 1.2 mL of 10% sodium sulfosalicylate was added to the precipitate sample proteins. After thorough vortexing, the sample was centrifuged at 12,000 r/min for 15 min at 4 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.22 μm aqueous phase filter before analysis. Free amino acid concentrations in the serum were determined using an automated amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) based on the principle of post-column ninhydrin derivatization.

2.5. Feed and Fecal Nutrients Determination

Water content was determined by drying to constant weight in an oven at 103 °C ± 2 °C; CP content was estimated by multiplying the total nitrogen content, determined using a Kjeltec 8400 analyzer (FOSS Analytical AB, Höganäs, Sweden), by a factor of 6.25. The ether extract content was determined using an automated extraction analyzer (Ankom Technology, Macedon, NY, USA). Ash content was determined by incineration in a muffle furnace at 550 °C to constant weight. Gross energy content of the diets and fecal samples was determined using an oxygen bomb calorimeter (Parr Instrument Company, Moline, IL, USA). Furthermore, the amino acid content in the feed was measured by hydrolyzing with 6 mol/L hydrochloric acid at 110 °C for 24 h, and then analyzing the sample using a fully automatic amino acid analyzer (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) based on the post-column derivatization principle with the indanone method.

2.6. Body Composition Measurement

The dry matter, CP, ether extract, ash, and gross energy content of the whole empty body were determined as described in the feed and fecal nutrients determination. By dividing the differences in body composition content by the corresponding experimental days, the daily deposition of water, protein, lipid, and ash (g/d) in piglets was calculated, as follows:

2.7. Intestinal Morphology Measurement

The intestinal segments fixed in 4% polyformaldehyde solution were processed through trimming, washing, dehydration, wax immersion, embedding, sectioning, and hematoxylin-eosin staining. The tissue samples were cut into sections of 3 µm thickness. To ensure representative sampling and avoid resampling the same structure, 5 serial sections were skipped between each evaluation. A total of 10 intact villi and crypts were measured per section using the Case Viewer image analysis software (3DHISTECH, CaseViewer2.2, Budapest, Hungary).

2.8. Colon Gut Microbiota

According to the method by He et al. [

18], total genomic DNA was extracted from the colon contents using the QIAamp PowerFecal DNA Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The V3–V4 hypervariable regions of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using primers 338F (5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′) and 806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′). Sequencing libraries were generated using the TruSeq

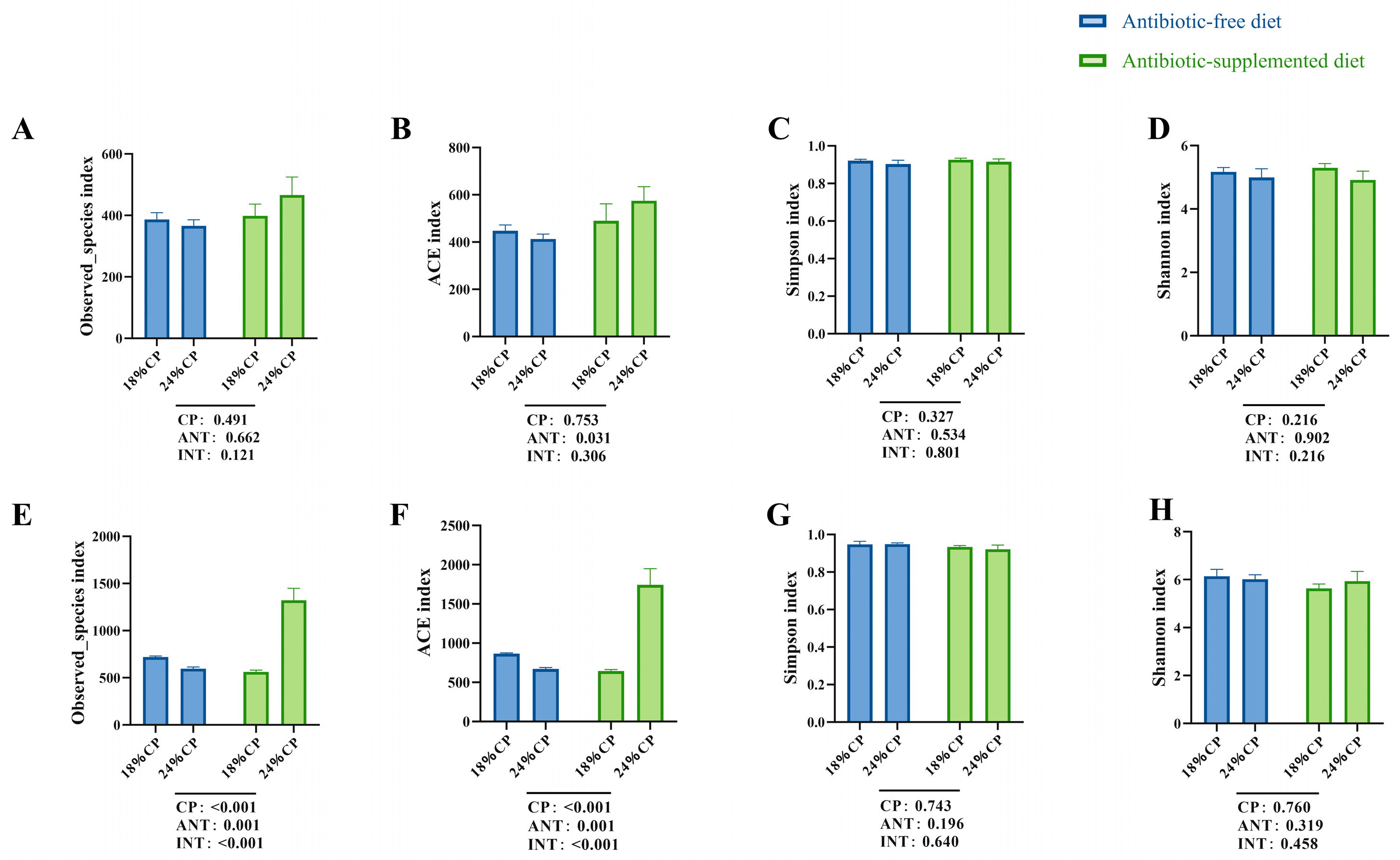

® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation Kit and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform. Raw reads were quality-filtered based on Q20/Q30 scores, and chimeric sequences were removed to obtain effective tags. These valid sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% identity using Uparse (v7.0.1001). Taxonomic annotation was performed using the Mothur method against the SILVA 138 database, while phylogenetic relationships were analyzed using MUSCLE (Version 3.8.31). Finally, data were normalized to the minimum sample depth for α- and β-diversity calculations.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA using SPSS 20 software to analyze the general univariate linear model, determining the main effects of CP treatment, antibiotic treatment, and their interaction. For parameters showing a significant interaction effect (p < 0.05), an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was performed, and the means were separated using Duncan’s multiple range test at p < 0.05 significance. Prism 8.0 software was used for colonic microbiota analysis and visualization. Statistical significance was declared at p < 0.05, and tendencies were declared at 0.05 < p < 0.10. Data were presented as means ± SEM.

4. Discussion

This study found that a dietary CP level of 18% significantly decreased the growth performance of piglets two weeks post-weaning compared to a 24% CP diet, consistent with the findings from Wellock et al. [

19]. Additionally, this study found that although the 18% CP level groups from 0 to 14 days reduced the growth performance of weaned piglets, after restoring the feed to a 19% CP level during the S2 phase, the piglets exhibited some compensatory growth. Therefore, there was no difference in the number of experimental days and ADG from 0 to 25 kg among the piglet groups. Stein et al. investigated the effects of feeding weaned piglets diets containing either 20.8% or 15.7% CP from days 0 to 14, followed by either 17.5% or 19.3% CP from days 15 to 35 [

20]. They found that piglets receiving the 15.7% CP diet from days 0 to 14 exhibited reduced growth performance, but their growth was compensated when fed the 19.3% CP diet from days 15 to 35. Similarly, Shi et al. reported that piglets experiencing early-stage protein restriction, followed by restoration to normal protein levels, underwent compensatory growth [

21]. The findings of the present study were consistent with those previously reported. This study found that dietary antibiotic supplementation did not significantly improve the growth performance of weaned piglets, consistent with the findings of Holt et al. [

22], but inconsistent with those of Diana et al. [

23], Kyriakis et al. [

24], and Weber et al. [

25]. Holt et al. [

22] found that antibiotics had little effect on the growth performance of piglets reared in clean, isolated facilities with high labor input. The positive effects of antibiotics were usually associated with their ability to suppress the growth of certain pathogenic microorganisms [

10]. The lack of significant improvement in growth performance with antibiotic supplementation observed in this study may be attributed to the high sanitary conditions of the experimental environment. The piglets were housed in a controlled research facility with strict biosecurity measures, regular cleaning protocols, and optimal environmental management.

The early stage after weaning is considered one of the most effective periods for converting nutrients into animal tissue [

26]. As expected, the body composition of piglets in the first two weeks after weaning was closely related to the CP level in the feed. With the increase in CP level in the feed, the protein content, protein deposition rate, and protein deposition energy in the piglets’ bodies increased, which was consistent with the research results from Conde-Aguilera et al. [

27] and Ruiz-Ascacibar et al. [

28]. The protein deposition rate was mainly determined by the pig’s lean meat growth potential [

29], which suggested that the 18% CP supply in this study may have limited the pig’s genetic potential, despite the amino acid requirements being met. Therefore, it was not only necessary to ensure the required amino acid needs, but also to guarantee the protein (total nitrogen) needs to achieve the pig’s maximum protein deposition capacity. This study also found that with the increase in CP level in the feed, the ratio of body lipid to body protein decreased significantly, and the body lipid content, body lipid deposition rate, and body lipid energy decreased. Morazán et al. [

30] and Skiba et al. [

31] reported that pigs fed a low-protein, balanced, amino acid feed were more obese than those fed high-protein feed. This phenomenon may be due to the low protein deposition rate in animals fed low-protein feed, resulting in a large amount of energy being stored as body lipid. While the protein deposition rate increased with the increase in CP level in the feed, the energy stored as body lipid decreased [

32]. Studies have shown that body water or body ash content is closely related to body protein content, reflecting the accompanying changes in body protein [

33,

34]. Therefore, the ratio of body water to body protein or the ratio of body ash to body protein should remain constant under different CP treatments. This study found that increasing the CP level in the feed did not significantly affect the ratio of body water to body protein, but significantly decreased the ratio of body ash to body protein. Oresanya et al. [

35] also found that the body water–protein ratio was not affected by the feed level, but the ratio of body ash to protein decreased with the increase in feed level, and speculated that it was due to the faster protein deposition rate than the body ash deposition rate, resulting in a decrease in the ratio of body ash to protein. The results of this study were consistent with those of Oresanya et al. [

35], as the piglets in this study had a high protein deposition capacity and had not yet reached their protein deposition limit. This study found that although reducing the CP level from 0 to 14 days decreased the protein deposition rate of weaned piglets, there was no difference in the protein deposition rate from 0 to 25 kg among the groups after the feed was restored to a normal CP level from 15 days to 25 kg. This suggested that piglets fed low-protein feed may have undergone compensatory protein deposition in the later stage. Bikker et al. [

36], Carstens et al. [

37], and Drouillard et al. [

38] all reported that compensatory protein deposition occurred after a period of nutritional restriction, and the results of this study were consistent with theirs. Additionally, the present study revealed no significant impact of dietary antibiotics on body composition and deposition rates in weaned piglets at both day 14 and 25 kg BW.

Apparent digestibility of nutrients reflects the capacity of animals to digest and absorb nutrients from their diet. Greater digestive and absorptive capacity is beneficial for animal growth [

39]. Bikker et al. [

6] reported that piglets fed a 22% CP diet had higher apparent CP digestibility than those fed a 15% CP diet, but apparent ether extract digestibility was not significantly affected. These findings were largely consistent with the present study, where piglets fed a 24% CP diet had higher apparent CP and gross energy digestibility than those fed an 18% CP diet, with no significant effect on apparent ether extract digestibility. The apparent nutrient digestibility results from these studies indicated that apparent nutrient digestibility in piglets improved with age and also reflected the relatively low apparent CP digestibility in piglets immediately post-weaning, which explained why low-protein diets were used for weaned piglets at higher risk of diarrhea.

Serum urea nitrogen can serve as an indicator of dietary protein quality and animal nitrogen intake, as well as a response parameter for determining animal protein requirements [

40]. This study found that feeding 24% levels of CP increased serum urea nitrogen content in weaned piglets, which was consistent with previous reports [

39,

41,

42]. This may be due to the increased absorption and breakdown of CP in weaned piglets, leading to an increase in serum urea nitrogen content. Serum triglyceride and cholesterol content can reflect the lipid metabolism status of animals [

43]. This study found that 24% CP levels decreased serum triglyceride content, indicating that increasing dietary CP levels reduced lipid synthesis. Morise et al. [

44] reported that piglets consuming less protein between 7 and 28 days of age increased lipid deposition. Morazán et al. [

30] and Ruusunen et al. [

29] also reported that pigs fed low-protein diets were more obese compared to those fed normal-protein diets. This observation aligned with the protein leverage hypothesis, which suggested that animals prioritize meeting their protein requirements; consequently, when fed low-protein diets, they tended to overconsume total energy to reach their protein target, leading to increased fat accumulation [

45,

46]. Furthermore, the surplus energy not utilized for protein synthesis was repartitioned towards lipogenesis. Additionally, this study found that adding antibiotics to the feed did not affect serum urea nitrogen, triglyceride, and cholesterol content in weaned piglets. Furthermore, this study found that early dietary CP levels and antibiotics did not have a significant impact on subsequent serum biochemical parameters in piglets at 25 kg, which was consistent with the results of subsequent growth performance.

The concentration of free amino acids in serum can reflect the physiological condition and nutritional status of animals [

43]. Serum amino acid concentration is influenced by factors such as protein synthesis and degradation, amino acid transport and metabolism, and gut microbiota structure, and is an intermediate of the body’s metabolic process [

47,

48]. Proteins in feed are hydrolyzed into amino acids under the action of proteases and peptidases secreted by the host and gut microbiota, and are then absorbed by amino acid transporters in the gut. This study found that despite the consistent levels of lysine, threonine, valine, glycine, and isoleucine in each feed group, the 24% CP level in feed significantly decreased the serum concentrations of threonine, valine, isoleucine, glycine, and lysine in weaned piglets. The reason for this phenomenon may be that the increased CP level in feed reduced the amount of crystalline amino acids added, and the absorption rate of crystalline amino acids was much higher than that of amino acids produced by protein degradation. Meanwhile, this study also found that providing antibiotics in the diet from days 0 to 14 significantly increased glycine concentration but did not have a significant impact on subsequent serum amino acid concentrations when weaned piglets reached a BW of 25 kg. These findings were consistent with the research results reported by Yu et al. [

49].

The gastrointestinal tract is the primary site for the digestion and absorption of nutrients in animals, and its pH significantly affects the normal physiological function. A suitable acidic environment in the gastrointestinal tract not only ensures the activity of digestive enzymes, promotes the digestion and absorption of nutrients, but also improves the balance of the microbial community [

50]. Wellock et al. reported that the pH of the contents in the ileum, cecum, proximal colon, and distal colon of piglets 14 days after weaning was not affected by the level of crude protein in the diet (13%, 18%, and 23%) [

19]. Htoo et al. also reported that feeding piglets with high or low crude protein diets did not affect the pH of the contents in the ileum and cecum [

5]. This study found that the pH of the gastrointestinal tract contents in weaned piglets was not affected by the level of CP in the diet with or without antibiotics, which was consistent with their results. The morphological characteristics of the small intestine are an important indicator of the integrity of the intestinal mucosa and its absorptive function in pigs [

51]. The villi and crypts in the small intestine are tubular structures formed by the migration of epithelial cells towards the intestinal lumen, and their structure directly affects the digestion and absorption of nutrients [

52]. A decrease in villus height and an increase in crypt depth indicate atrophy of the intestinal mucosa and a decrease in absorptive capacity. Therefore, the villus height to crypt depth ratio is often used to reflect the functional status of the small intestine. Pearce et al. [

53] reported that feeding 17% CP and 24% CP diets to weaned piglets had no significant effect on the villus height, crypt depth, and villus height to crypt depth ratio in the small intestine, which was consistent with the results of this study.

The gut microbiota and its metabolites play a crucial role in animal health, and feed is one of the main factors influencing the composition of the gut microbiota [

16,

54,

55]. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of different CP levels in feed with or without antibiotics on the gut microbiota of weaned piglets. In the absence of antibiotics, this study found that compared to feed with 24% CP, the addition of 18% CP significantly improved the relative abundance of beneficial

Lactobacillus in the colon of weaned piglets at 25 kg BW, but not at 0–14 d. Lactobacillus is a beneficial bacterium that can help maintain gut health and enhance immune system function [

56]. This study found that compared to the diet without added antibiotics, the addition of antibiotics from day 0 to 14 significantly decreased the relative abundance of

Pseudoramibacter in the colon of weaned piglets on day 14. However, after stopping the use of antibiotics from day 15 to 25 kg, there was a significant increase in the relative abundance of

Megasphaera in the colon of piglets at 25 kg. In the context of the porcine gut,

Megasphaera is functionally important as a lactate-utilizing bacterium that produces short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), particularly butyrate and valerate [

57]. The increase in its abundance suggested a recovery of the gut’s capacity to convert lactate into beneficial metabolites following antibiotic withdrawal. The results of this study indicated that feeding high levels of CP during the S1 phase reduced the abundance of beneficial bacteria. Feeding antibiotics during the S1 phase reduced the production of harmful bacteria, while stopping antibiotics in the subsequent S2 phase increased the abundance of harmful bacteria.