Appropriate Rumen-Protected Glutamine Supplementation During Late Gestation in Ewes Promotes Lamb Growth and Improves Maternal and Neonatal Metabolic, Immune and Microbiota Functions

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Diets for Gestating Ewes

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Milk Composition Analysis

2.4. Measurement of Serum Biochemical Parameters, Antioxidant Indicators, and Inflammatory Cytokines

2.5. Microbial 16S rRNA Sequencing

2.6. Serum Metabolome Measurement

2.7. Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Processing of Microbiome Data

2.7.2. Processing of Metabolome Data

3. Results

3.1. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on Early Growth Performance and Organ Development of Offspring Lambs

3.2. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on the Composition of Colostrum and Mature Milk

3.3. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on Serum Biochemical Parameters in Ewes and Their Offspring

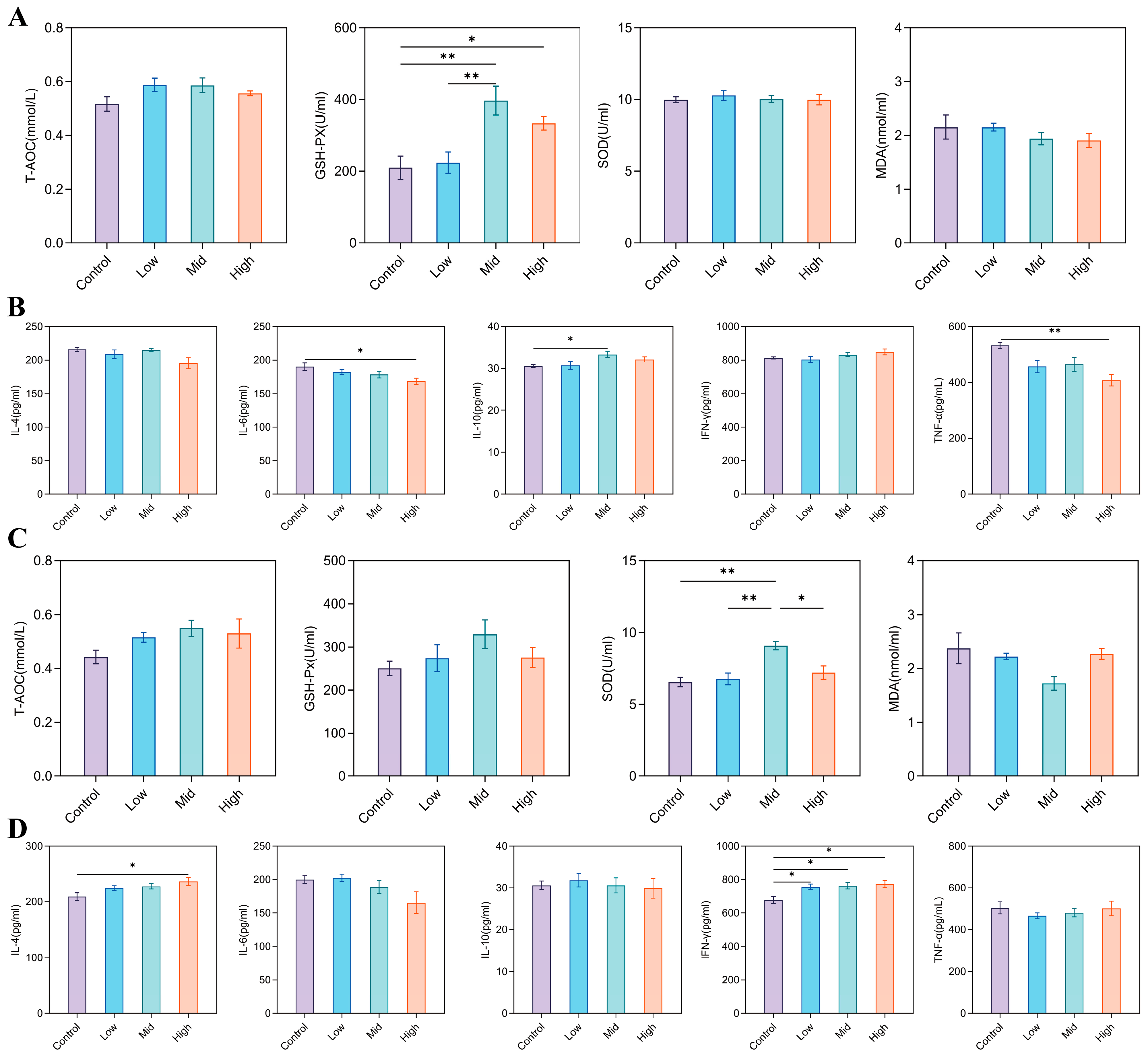

3.4. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on Serum Antioxidant Indicators and Inflammatory Cytokines in Ewes and Their Offspring

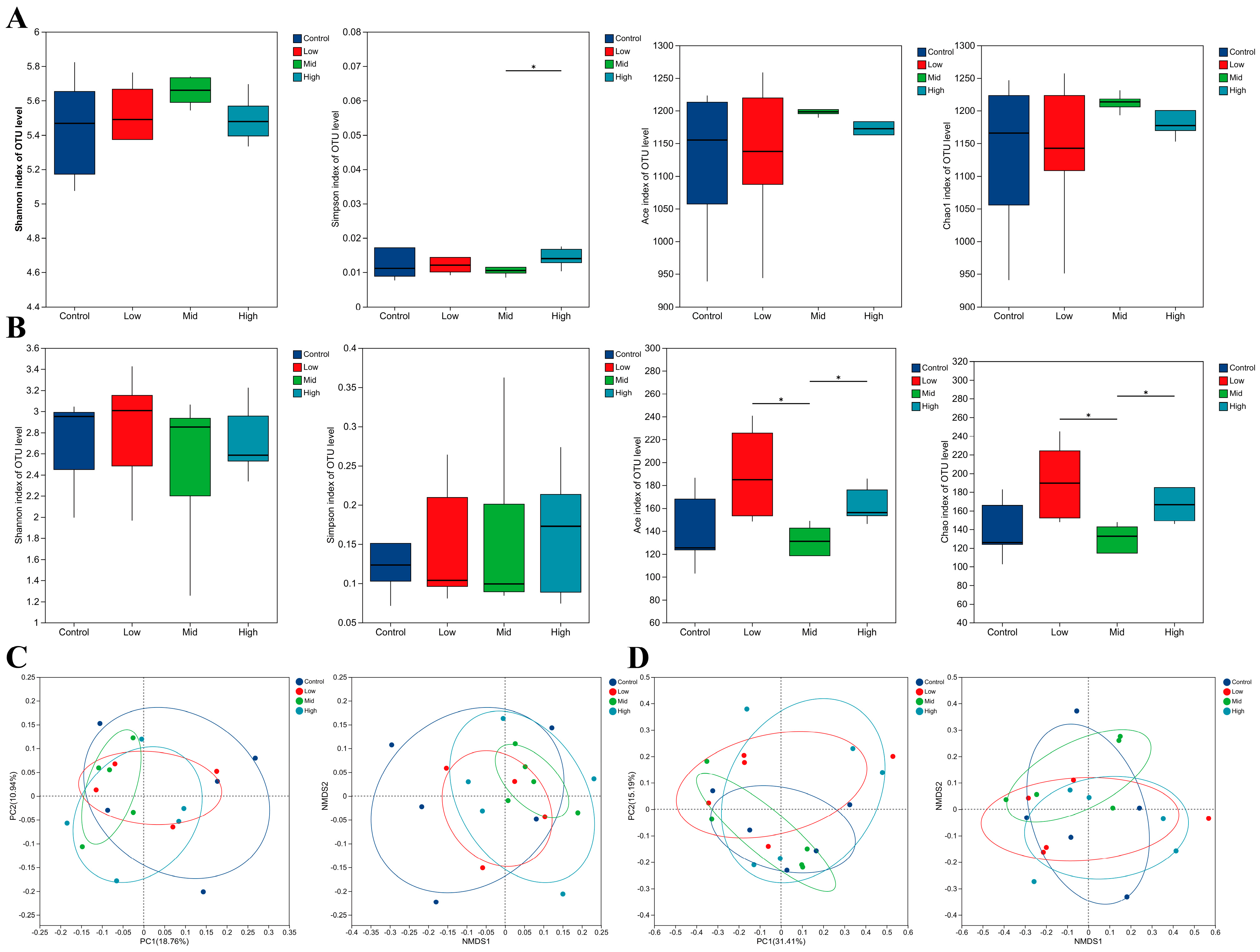

3.5. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on the Rectal Fecal Microbiota of Ewes and Their Offspring

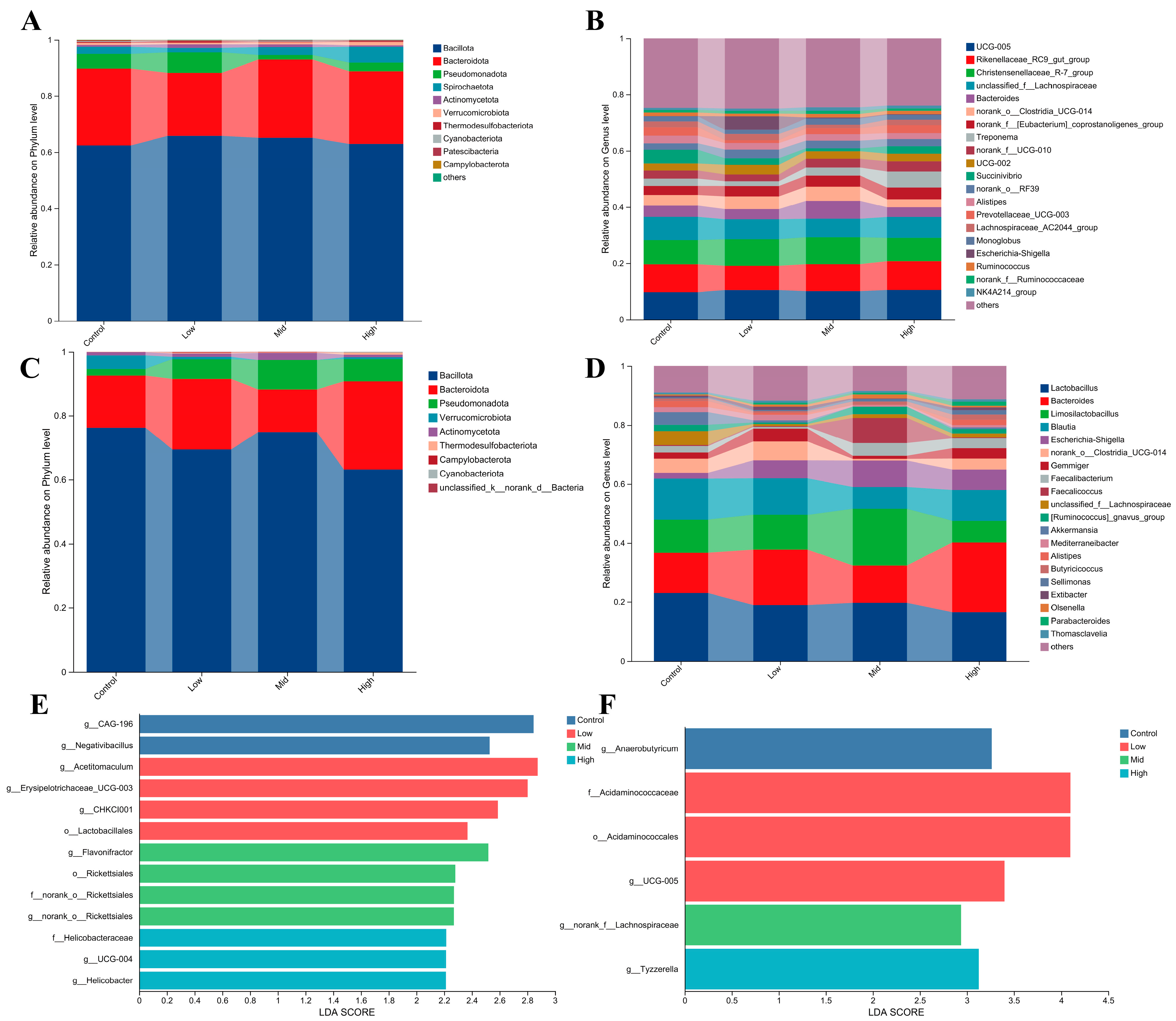

3.6. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on Rectal Microbiota Composition and Core Microbiota in Ewes and Their Offspring

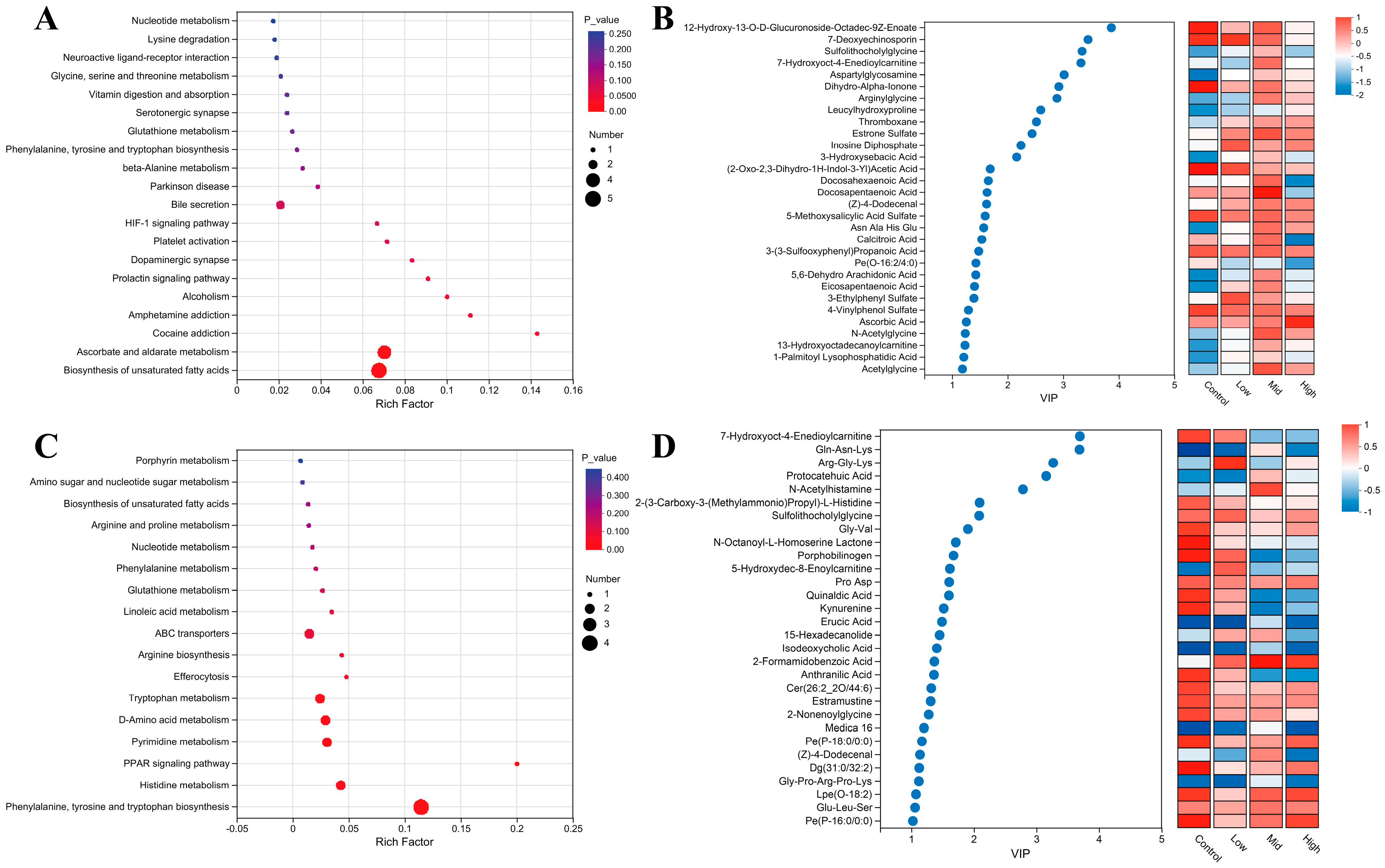

3.7. Serum Metabolic Profiling in Ewes and Lambs Following RP-Gln Supplementation

3.8. Effects of RP-Gln Supplementation in Ewes During Late Gestation on Serum Metabolic Pathways in Ewes and Their Offspring

3.9. Correlation Analysis of Rectal Microbiota-Metabolite Interactions and Their Associations with Oxidative and Inflammatory Status in Ewes and Their Offspring Supplemented with RP-Gln During Late Gestation

4. Discussion

4.1. Mid-Level RP-Gln Supplementation as the Optimal Dose for Enhancing Growth Performance

4.2. Improvements in Maternal and Offspring Metabolic and Antioxidant Status Following RP-Gln Supplementation

4.3. Dose-Dependent Immunomodulatory Effects and Gut Microbiota Remodeling Induced by RP-Gln

4.4. Divergent Microbial Responses: Enrichment of Beneficial Taxa at Mid Dose Versus Pathogen Expansion at High Dose

4.5. Metabolomic Evidence for Maternal–Fetal Metabolic Reprogramming Under RP-Gln Supplementation

4.6. Limitations and Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| A/G | Albumin-to-Globulin Ratio |

| ALB | Albumin |

| ALT | Alanine Aminotransferase |

| AST | Aspartate Aminotransferase |

| CK | Creatine Kinase |

| GGT | Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase |

| GLB | Globulin |

| GSH-Px | Glutathione Peroxidase |

| HBDH | Hydroxybutyrate Dehydrogenase |

| HDL | High-Density Lipoprotein |

| IFN-γ | Interferon-gamma |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| LDH | Lactate Dehydrogenase |

| LDL | Low-Density Lipoprotein |

| MDA | Malondialdehyde |

| PUFAs | Polyunsaturated fatty acids |

| RP-Gln | Rumen-protected glutamine |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

| T-AOC | Total Antioxidant Capacity |

| TC | Total Cholesterol |

| TG | Triglycerides |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| TP | Total Protein |

References

- Elgazzaz, M.; Berdasco, C.; Garai, J.; Baddoo, M.; Lu, S.; Daoud, H.; Zabaleta, J.; Mauvais-Jarvis, F.; Lazartigues, E. Maternal Western Diet Programs Cardiometabolic Dysfunction and Hypothalamic Inflammation via Epigenetic Mechanisms Predominantly in the Male Offspring. Mol. Metab. 2024, 80, 101864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, K.; Maldonado-Ruiz, R.; Camacho-Morales, A.; de la Garza, A.L.; Castro, H. Maternal Methyl Donor Supplementation Regulates the Effects of Cafeteria Diet on Behavioral Changes and Nutritional Status in Male Offspring. Food Nutr. Res. 2023, 67, 9828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symonds, M.E.; Stephenson, T.; Gardner, D.S.; Budge, H. Long-Term Effects of Nutritional Programming of the Embryo and Fetus: Mechanisms and Critical Windows. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2007, 19, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernigliaro, F.; Santangelo, A.; Nardello, R.; Lo Cascio, S.; D’Agostino, S.; Correnti, E.; Marchese, F.; Pitino, R.; Valdese, S.; Rizzo, C.; et al. Prenatal Nutritional Factors and Neurodevelopmental Disorders: A Narrative Review. Life 2024, 14, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, L.; Kongsted, A.H.; Ghoreishi, S.M.; Takhtsabzy, T.K.; Friedrichsen, M.; Hellgren, L.I.; Kadarmideen, H.N.; Vaag, A.; Nielsen, M.O. Pre- and Early-Postnatal Nutrition Modify Gene and Protein Expressions of Muscle Energy Metabolism Markers and Phospholipid Fatty Acid Composition in a Muscle Type Specific Manner in Sheep. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadzadeh-Gavahan, L.; Hosseinkhani, A.; Palangi, V.; Lackner, M. Supplementary Feed Additives Can Improve Lamb Performance in Terms of Birth Weight, Body Size, and Survival Rate. Animals 2023, 13, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, D.; Mukherjee, S.; Anand, P.S.S.; Kumar, P.; Suresh, V.R.; Vijayan, K.K. Nutritional Profiling of Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha) of Different Size Groups and Sensory Evaluation of Their Adults from Different Riverine Systems. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esperança-Martins, M.; Fernandes, I.; Soares do Brito, J.; Macedo, D.; Vasques, H.; Serafim, T.; Costa, L.; Dias, S. Sarcoma Metabolomics: Current Horizons and Future Perspectives. Cells 2021, 10, 1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.; Suh, D.H.; Lee, S.; Kim, H.S.; Cho, S.H.; Woo, Y.R. Associations between Skin Microbiome and Metabolome in the Pathogenesis of Atopic Dermatitis Patients with Scalp Involvement. Allergy Asthma Immunol. Res. 2024, 16, 668–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.-K.; Lin, C.-Y.; Kang, C.-J.; Liao, C.-T.; Wang, W.-L.; Chiang, M.-H.; Yen, T.-C.; Lin, G. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Metabolomics Biomarkers for Identifying High Risk Patients with Extranodal Extension in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuai, T.; Tian, X.; Xu, L.-L.; Chen, W.-Q.; Pi, Y.-P.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Q.-Q.; Li, X.-E. Oral Glutamine May Have No Clinical Benefits to Prevent Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis in Adult Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Han, W.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Qin, T.; Zhang, C.; Shi, M.; Han, S.; Gao, B.; et al. Glutamine Suppresses Senescence and Promotes Autophagy through Glycolysis Inhibition-Mediated AMPKα Lactylation in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeGrand, E.K. Beyond Nutritional Immunity: Immune-Stressing Challenges Basic Paradigms of Immunometabolism and Immunology. Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1508767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Bai, J.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Z. Low-Protein Diet Supplemented with 1% L-Glutamine Improves Growth Performance, Serum Biochemistry, Redox Status, Plasma Amino Acids, and Alters Fecal Microbiota in Weaned Piglets. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 17, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selle, P.H.; Macelline, S.P.; Toghyani, M.; Liu, S.Y. The Potential of Glutamine Supplementation in Reduced-Crude Protein Diets for Chicken-Meat Production. Anim. Nutr. 2024, 18, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reicher, N.; Melkman-Zehavi, T.; Dayan, J.; Uni, Z. Intra-Amniotic Administration of l-Glutamine Promotes Intestinal Maturation and Enteroendocrine Stimulation in Chick Embryos. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Q.; Xing, Z.; Liao, J.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, R.; Wang, S.; Wang, C.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y. Effects of Glutamine on Rumen Digestive Enzymes and the Barrier Function of the Ruminal Epithelium in Hu Lambs Fed a High-Concentrate Finishing Diet. Animals 2022, 12, 3418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, F.; Kong, F.; Cao, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Bi, Y.; Li, S. Effect of Supplementing Different Levels of L-Glutamine on Holstein Calves during Weaning. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G.; Bazer, F.W.; Johnson, G.A.; Satterfield, M.C.; Washburn, S.E. Metabolism and Nutrition of L-Glutamate and L-Glutamine in Ruminants. Animals 2024, 14, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, T.; Murtaza, G.; Metwally, E.; Kalhoro, D.H.; Kalhoro, M.S.; Rahu, B.A.; Sahito, R.G.A.; Yin, Y.; Yang, H.; Chughtai, M.I.; et al. The Role of Oxidative Stress and Antioxidant Balance in Pregnancy. Mediat. Inflamm. 2021, 2021, 9962860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaraju, I.; Sana, M.; Chakraborty, I.; Rahman, M.H.; Biswas, R.; Mazumder, N. Dietary Acrylamide: A Detailed Review on Formation, Detection, Mitigation, and Its Health Impacts. Foods 2024, 13, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, A.; Jagtap, S.; Vyavahare, S.; Deshpande, M.; Harsulkar, A.; Ranjekar, P.; Prakash, O. Phytochemicals in the Treatment of Inflammation-Associated Diseases: The Journey from Preclinical Trials to Clinical Practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1177050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Cai, X.; Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, H.; He, J.; Fang, Z.; Feng, B.; Tang, J.; Lin, Y.; et al. Effects of Melatonin Supplementation during Pregnancy on Reproductive Performance, Maternal–Placental–Fetal Redox Status, and Placental Mitochondrial Function in a Sow Model. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Nutrient Requirements of Meat-Type Sheep and Goat; NY/T 816-2021; Replaces NY/T 816-2004; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Xianbang, W.; Mingping, L.; Kunliang, L.; Qiang, H.; Dongkang, P.; Haibin, M.; Guihua, H. Effects of Intercropping Teak with Alpinia katsumadai Hayata and Amomum longiligulare T.L. Wu on Rhizosphere Soil Nutrients and Bacterial Community Diversity, Structure, and Network. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1328772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, S.; Wang, W.; Dai, Z.; Feng, C.; Wu, G.; Wang, J. Maternal L-Glutamine Supplementation during Late Gestation Alleviates Intrauterine Growth Restriction-Induced Intestinal Dysfunction in Piglets. Amino Acids 2018, 50, 1289–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, J.; Ochoa, J.B.; Correia, M.I.T.; Munera-Seeley, V.; Popovic, P.J. Effect of Citrulline and Glutamine on Nitric Oxide Production in RAW 264.7 Cells in an Arginine-Depleted Environment. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2008, 32, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosario, F.J.; Urschitz, J.; Razavy, H.; Elston, M.; Powell, T.L.; Jansson, T. PiggyBac Transposase-Mediated Inducible Trophoblast-Specific Knockdown of Mtor Decreases Placental Nutrient Transport and Fetal Growth. Clin. Sci. 2025, 139, 825–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olaniyi, K.S.; Olatunji, L.A. L-Glutamine Ameliorates Adipose-Hepatic Dysmetabolism in OC-Treated Female Rats. J. Endocrinol. 2020, 246, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Albrecht, E.; Sciascia, Q.L.; Li, Z.; Görs, S.; Schregel, J.; Metges, C.C.; Maak, S. Effects of Oral Glutamine Supplementation on Early Postnatal Muscle Morphology in Low and Normal Birth Weight Piglets. Animals 2020, 10, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.-S.; Chen, Y.-T.; Li, X.; Hsueh, P.-C.; Tzeng, S.-F.; Chen, H.; Shi, P.-Z.; Xie, X.; Parik, S.; Planque, M.; et al. Author Correction: CD40 Signal Rewires Fatty Acid and Glutamine Metabolism for Stimulating Macrophage Anti-Tumorigenic Functions. Nat. Immunol. 2023, 24, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazir, U.; Fu, Z.; Zheng, X.; Zafar, M.H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, H. Effects of Alanyl-Glutamine Dipeptide Supplementation on Growth Performance, Nutrient Digestibility, Digestive Enzyme Activity, Immunity, and Antioxidant Status in Growing Laying Hens. Animals 2024, 14, 2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalaifah, H.; Tolba, S.A.; Al-Nasser, A.; Gouda, A. Effects of Glutamine Supplementation and Early Cold Conditioning on Cold Stress Adaptability in Broilers. Animals 2025, 15, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Qiu, W.; Li, G.; Guo, H.; Dai, S.; Li, G. Effects of Glutamine Supplementation on the Growth Performance, Antioxidant Capacity, Immunity and Intestinal Morphology of Cold-Stressed Prestarter Broiler Chicks. Vet. Res. Commun. 2025, 49, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.L.; Pazdro, R. Impact of Supplementary Amino Acids, Micronutrients, and Overall Diet on Glutathione Homeostasis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, M.J.; Dudash, H.J.; Docherty, M.; Geronilla, K.B.; Baker, B.A.; Haff, G.G.; Cutlip, R.G.; Alway, S.E. Vitamin E and C Supplementation Reduces Oxidative Stress, Improves Antioxidant Enzymes and Positive Muscle Work in Chronically Loaded Muscles of Aged Rats. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 882–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zha, X.; Zhang, B.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, X.; Elsabagh, M.; Ma, Y.; Wang, H.; Shu, G.; Wang, M. Dietary Rumen-Protected L-Arginine or N-Carbamylglutamate Enhances Placental Amino Acid Transport and Suppresses Angiogenesis and Steroid Anabolism in Underfed Pregnant Ewes. Anim. Nutr. 2023, 15, 149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Yang, Q.; Liu, N.; Zhong, Q.; Sun, Z. The Effects of Glutamine Supplementation on Liver Inflammatory Response and Protein Metabolism in Muscle of Lipopolysaccharide-Challenged Broilers. Animals 2024, 14, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, K.D.; Wischmeyer, P.E. Glutamine Attenuates Inflammation and NF-kB Activation via Cullin-1 Deneddylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 373, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, L.; Xiong, D.; Kang, X.; Jiao, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wu, K.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, X.; Pan, Z. The Optimized Fusion Protein HA1-2-FliCΔD2D3 Promotes Mixed Th1/Th2 Immune Responses to Influenza H7N9 with Low Induction of Systemic Proinflammatory Cytokines in Mice. Antivir. Res. 2019, 161, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perna, S.; Alalwan, T.A.; Alaali, Z.; Alnashaba, T.; Gasparri, C.; Infantino, V.; Hammad, L.; Riva, A.; Petrangolini, G.; Allegrini, P.; et al. The Role of Glutamine in the Complex Interaction between Gut microbiota and Health: A Narrative Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saravanan, P.; Pooja, R.; Balachander, N.; Kesav, R.S.K.; Silpa, S.; Rupachandra, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Wound Healing Properties of Lactic Acid Bacteria and Its Peptides. Folia Microbiol. 2023, 68, 337–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Xie, Q.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Q.; Zhao, L.; Evivie, S.E.; Li, B.; Huo, G. Gut microbiota Modulation and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Mixed Lactobacilli in Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Colitis in Mice. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 5130–5143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.-J.; Chen, Y.-T.; Ko, J.-L.; Chen, J.-Y.; Zheng, J.-Y.; Liao, J.-W.; Ou, C.-C. Butyrate Modulates Gut microbiota and Anti-Inflammatory Response in Attenuating Cisplatin-Induced Kidney Injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 181, 117689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, L. Butyrate-Producing Bacteria Increase Gut microbiota Diversity to Delay Intestinal Inflammaging. Innov. Aging 2023, 7, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Rios-Covian, D.; Huillet, E.; Auger, S.; Khazaal, S.; Bermúdez-Humarán, L.G.; Sokol, H.; Chatel, J.-M.; Langella, P. Faecalibacterium: A Bacterial Genus with Promising Human Health Applications. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2023, 47, fuad039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.-B.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Huang, H.-H.; Lin, J. Prospects for Clinical Applications of Butyrate-Producing Bacteria. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2021, 10, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, T.; Zheng, C.; Wang, F.; Liu, T.; Yuan, C.; Lu, Z. Multi-Omics Insights into Key Microorganisms and Metabolites in Tibetan Sheep’s High-Altitude Adaptation. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1616555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Peng, C.; Geng, Y.; Zhou, F.; Han, Y.; Hou, X. Characteristics of Gut microbiota of Term Small Gestational Age Infants within 1 Week and Their Relationship with Neurodevelopment at 6 Months. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 912968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, S.-A.; Seifert, J.; Camarinha-Silva, A.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Hernández-Arriaga, A.; Hudler, M.; Windisch, W.; König, A. Microbiota and Nutrient Portraits of European Roe Deer (Capreolus capreolus) Rumen Contents in Characteristic Southern German Habitats. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 3082–3096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holecek, M. Side Effects of Long-Term Glutamine Supplementation. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2013, 37, 607–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.; He, B.; Qin, Y.; Yang, B.; Yu, Z.; Wang, J. Maternal Rumen Bacteriota Shapes the Offspring Rumen Bacteriota, Affecting the Development of Young Ruminants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03590-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Yan, H.; Tian, P.; Ji, S.; Zhao, W.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. The Effect of Early Colonized Gut microbiota on the Growth Performance of Suckling Lambs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1273444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, D.; Liu, C.; Qin, M.; Zhang, X.; Xi, T.; Yuan, S.; Hao, H.; Xiong, J. Metabolic Dysregulation and Emerging Therapeutical Targets for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 558–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, E.; Domaradzki, P.; Drabik, K.; Kasperek, K.; Puzio, I.; Burmańczuk, A.; Batkowska, J.; Arciszewski, M.B.; Muszyński, S. Long-Term Dietary Glutamine Supplementation Modulates Fatty Acid Profile and Health Indices in Quail Meat. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roque-Jiménez, J.A.; Oviedo-Ojeda, M.F.; Whalin, M.; Lee-Rangel, H.A.; Relling, A.E. Ewe Early Gestation Supplementation with Eicosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic Acids Affects the Liver, Muscle, and Adipose Tissue Fatty Acid Profile and Liver mRNA Expression in the Offspring. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, skad144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szilagyi, J.T.; Avula, V.; Fry, R.C. Perfluoroalkyl Substances (PFAS) and Their Effects on the Placenta, Pregnancy and Child Development: A Potential Mechanistic Role for Placental Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors (PPARs). Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 222–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, D.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.D.; Song, Z. Kynurenic Acid Acts as a Signaling Molecule Regulating Energy Expenditure and Is Closely Associated with Metabolic Diseases. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 847611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dooley, L.N.; Kuhlman, K.R.; Robles, T.F.; Eisenberger, N.I.; Craske, M.G.; Bower, J.E. The Role of Inflammation in Core Features of Depression: Insights from Paradigms Using Exogenously-Induced Inflammation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 94, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, L. Maternal Nutrient Metabolism in the Liver during Pregnancy. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1295677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa-Velazquez, M.; Pinos-Rodriguez, J.M.; Parker, A.J.; Relling, A.E. Maternal Supply of a Source of Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Methionine during Late Gestation on the Offspring’s Growth, Metabolism, Carcass Characteristic, and Liver’s mRNA Expression in Sheep. J. Anim. Sci. 2022, 100, skac032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Ingredient, % of DM 1 | Content |

|---|---|

| Corn silage | 20.00 |

| Alfalfa hay | 25.00 |

| Chinese wildrye hay | 20.00 |

| Corn | 19.00 |

| Soybean meal | 8.00 |

| Corn bran | 6.00 |

| Monocalcium phosphate | 0.50 |

| Salt | 0.50 |

| Premix 2 | 1.00 |

| Nutritional, % of DM 1 | |

| Metabolic energy 3, MJ/kg | 9.04 |

| Crude protein, % | 13.51 |

| Ether extract, % | 2.96 |

| Neutral detergent fiber, % | 43.45 |

| Acid detergent fiber, % | 27.21 |

| Crude ash, % | 0.59 |

| Calcium, % | 0.73 |

| Phosphorus, % | 0.44 |

| Rumen degradable protein, % | 8.99 |

| Rumen undegraded protein, % | 4.52 |

| Lysine, % | 0.64 |

| Methionine, % | 0.21 |

| Threonine, % | 0.49 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low | Mid | High | |||

| Colostrum (%) | ||||||

| Milk fat | 11.66 a | 9.29 b | 12.06 a | 10.86 ab | 0.54 | 0.01 |

| Non-fat milk solids | 21.74 | 19.99 | 21.02 | 20.20 | 1.53 | 0.84 |

| Lactose | 9.76 | 8.97 | 8.76 | 9.07 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| Solids | 1.66 | 1.52 | 1.61 | 1.54 | 0.11 | 0.80 |

| Milk protein | 10.30 | 9.48 | 9.95 | 9.56 | 0.72 | 0.84 |

| Regular milk (%) | ||||||

| Milk fat | 4.15 | 4.72 | 4.44 | 2.85 | 0.54 | 0.13 |

| Non-fat milk solids | 9.38 | 9.03 | 9.09 | 10.56 | 1.53 | 0.12 |

| Lactose | 4.20 | 4.05 | 4.08 | 4.74 | 0.80 | 0.12 |

| Solids | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.69 | 0.79 | 0.11 | 0.17 |

| Milk protein | 4.44 | 4.27 | 4.30 | 5.00 | 0.72 | 0.12 |

| Items | Groups | SEM | p-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Low | Mid | High | |||

| Ewes | ||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 16.70 | 16.80 | 15.90 | 17.40 | 2.27 | 0.95 |

| TP (g/L) | 65.39 | 66.94 | 59.96 | 64.27 | 2.62 | 0.11 |

| ALB (g/L) | 22.86 | 24.64 | 22.14 | 23.53 | 1.01 | 0.16 |

| GLB (g/L) | 42.53 | 42.39 | 37.82 | 40.74 | 2.23 | 0.20 |

| A/G | 0.55 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.60 | 0.04 | 0.54 |

| AST (U/L) | 85.00 | 83.60 | 68.60 | 78.00 | 6.00 | 0.07 |

| GGT (U/L) | 57.30 b | 65.20 ab | 70.70 a | 62.40 ab | 4.26 | 0.05 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 0.62 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 1.73 | 1.91 | 1.75 | 1.63 | 0.14 | 0.34 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.44 | 0.07 | 0.49 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 0.94 | 0.06 | 0.19 |

| CK (U/L) | 104.43 | 134.23 | 132.60 | 146.90 | 24.75 | 0.46 |

| HBDH (U/L) | 376.9 | 383.40 | 363.63 | 360.61 | 32.50 | 0.91 |

| LDH (U/L) | 382.06 | 365.67 | 387.82 | 365.49 | 33.84 | 0.90 |

| Lambs | ||||||

| ALT (U/L) | 7.00 ab | 9.40 a | 6.20 b | 6.00 b | 0.76 | 0.02 |

| TP/(g/L) | 64.30 | 66.12 | 66.68 | 65.34 | 1.39 | 0.65 |

| ALB (g/L) | 22.56 | 22.96 | 23.02 | 22.68 | 0.59 | 0.93 |

| GLB (g/L) | 41.74 | 43.16 | 43.66 | 42.86 | 1.28 | 0.75 |

| A/G | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.95 |

| AST (U/L) | 42.00 | 41.60 | 41.20 | 48.80 | 2.17 | 0.08 |

| GGT (U/L) | 124.20 b | 122.60 b | 216.60 a | 152.60 b | 15.04 | <0.01 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.04 | 0.41 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 1.94 b | 2.42 ab | 2.84 a | 3.03 a | 0.20 | 0.01 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 0.54 b | 0.72 ab | 0.93 a | 0.98 a | 0.07 | <0.01 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.03 b | 1.19 ab | 1.33 ab | 1.43 a | 0.08 | 0.01 |

| CK (U/L) | 356.84 a | 289.50 a | 211.76 b | 225.38 b | 17.96 | <0.001 |

| HBDH (U/L) | 409.12 b | 494.24 a | 401.76 b | 468.70 ab | 19.39 | 0.01 |

| LDH (U/L) | 494.88 ab | 566.42 ab | 484.08 b | 579.58 a | 21.80 | 0.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nie, Y.; Peng, X.; Li, J.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, F.; Jing, W.; Liu, Y.; Nie, C. Appropriate Rumen-Protected Glutamine Supplementation During Late Gestation in Ewes Promotes Lamb Growth and Improves Maternal and Neonatal Metabolic, Immune and Microbiota Functions. Animals 2026, 16, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010002

Nie Y, Peng X, Li J, Gao Z, Zhang F, Jing W, Liu Y, Nie C. Appropriate Rumen-Protected Glutamine Supplementation During Late Gestation in Ewes Promotes Lamb Growth and Improves Maternal and Neonatal Metabolic, Immune and Microbiota Functions. Animals. 2026; 16(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNie, Yifan, Xiangjian Peng, Jiahao Li, Zhentiao Gao, Fei Zhang, Wei Jing, Yanfeng Liu, and Cunxin Nie. 2026. "Appropriate Rumen-Protected Glutamine Supplementation During Late Gestation in Ewes Promotes Lamb Growth and Improves Maternal and Neonatal Metabolic, Immune and Microbiota Functions" Animals 16, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010002

APA StyleNie, Y., Peng, X., Li, J., Gao, Z., Zhang, F., Jing, W., Liu, Y., & Nie, C. (2026). Appropriate Rumen-Protected Glutamine Supplementation During Late Gestation in Ewes Promotes Lamb Growth and Improves Maternal and Neonatal Metabolic, Immune and Microbiota Functions. Animals, 16(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010002