Stable Isotope Analysis Reveals Habitat-Driven Dietary Niches of Lepus europaeus

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Population Decline and Environmental Drivers of the European Brown Hare

1.2. European Hare Diet

1.3. Hare Diet Investigation Methods

2. Materials and Methods

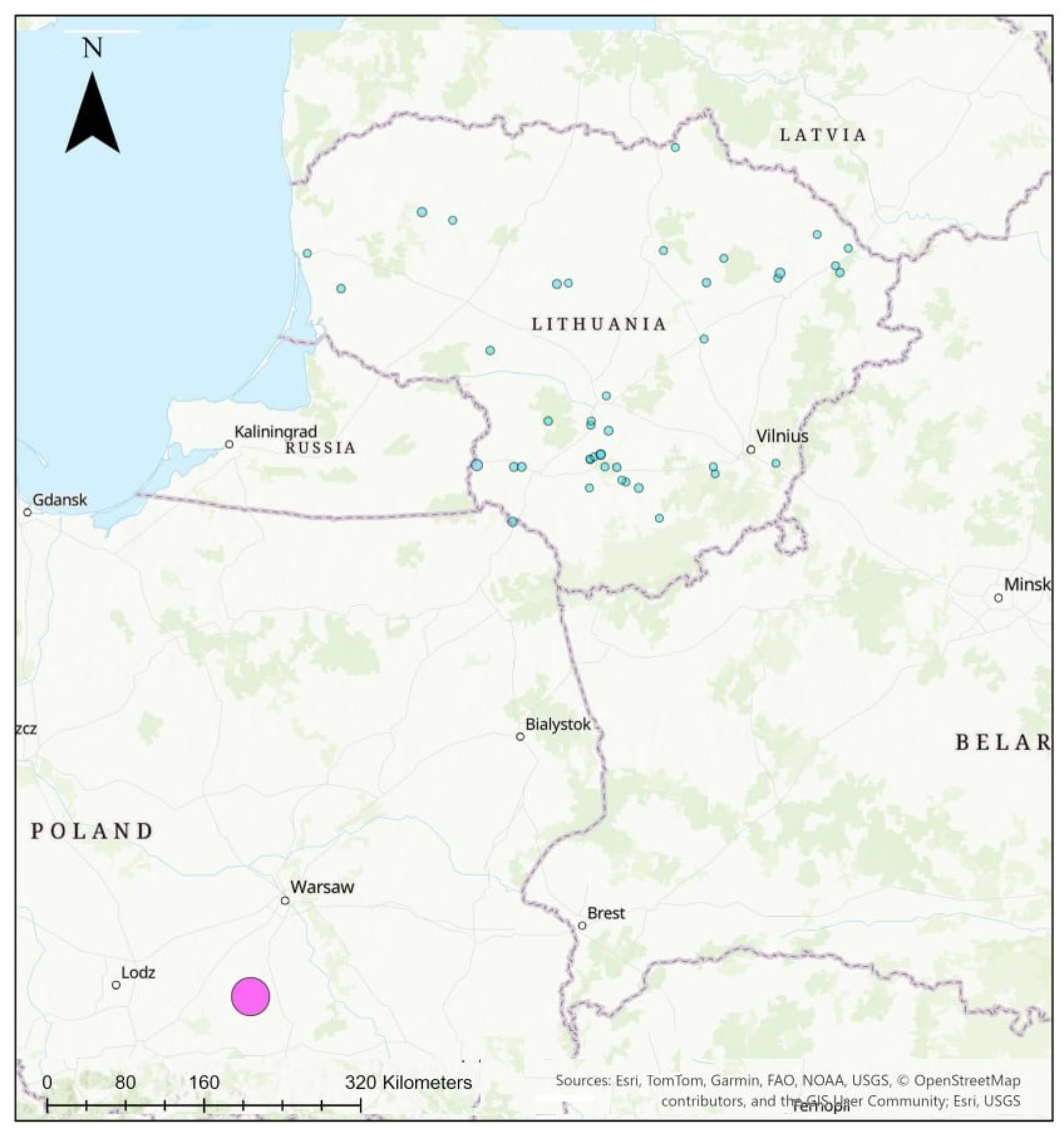

2.1. Study Sites and Habitats

2.2. Hair Collection and Sample Size

2.3. Age Identification in Sampled Hares

2.4. Stable Isotope Analysis of Hair

2.5. Statistical Data Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Environmental and Temporal Predictors of Stable Isotope Variation

3.2. Stable Isotope Variation Across Countries

3.3. Habitat Influence on Isotopic Signatures

3.4. Temporal Variation in Isotopic Signatures

3.5. Sex and Age Class Differences in Isotopic Signatures

4. Discussion

4.1. Decrease in European Brown Hare Numbers

4.2. Hare Dietary Specialization and Habitat Requirements

4.3. Agricultural Landscapes and Ecology of the European Brown Hare

4.4. Lepus Europaeus Diet Specific as Found from Isotopic Analysis

4.5. Ecological and Management Implications

4.6. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IUCN | The International Union for Conservation of Nature |

| AESs | Agri-environment Schemes |

| GLM | General Linear Model |

| SEAc | Small-sample Corrected Standard Ellipse Area |

| SEAb | Bayesian Standard Ellipse Area |

| SEA | Standard Ellipse Area |

| SIBER | Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R |

References

- Gryz, J.; Krauze-Gryz, D. Why Did Brown Hare Lepus europaeus Disappear from Some Areas in Central Poland? Diversity 2022, 14, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzarri, F.; Slamecka, J.; Sladecek, T.; Jurcik, R.; Ondruska, L.; Schultz, P. Long-Term Monitoring of European Brown Hare (Lepus europaeus) Population in the Slovak Danubian Lowland. Diversity 2024, 16, 486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Wieren, S.E.; Wiersma, M.; Prins, H.H. Climatic factors affecting a brown hare (Lepus europaeus) population. Lutra 2006, 49, 103–110. [Google Scholar]

- Johann, F.; Arnold, J. Scattered woody vegetation promotes European brown hare population. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2021, 56, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, A. Lepus europaeus (Lagomorpha: Leporidae). Mamm. Species 2020, 52, 125–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, P.J.; Fletcher, M.R.; Berny, P. Review of the factors affecting the decline of the European brown hare, Lepus europaeus (Pallas, 1778) and the use of wildlife incident data to evaluate the significance of paraquat. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2000, 79, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pėtelis, K.; Brazaitis, G. The European hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas) population in Lithuania: The status and causes of abundance change. Acta Biol. Univ. Daugavp. 2009, 9, 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kamieniarz, R.; Panek, M. Zwierzęta Łowne w Polsce na Przełomie XX i XXI Wieku [Game Animals in Poland at the Turn of the 20th and 21st Century]; Stacja Badawcza OHZ PZŁ: Czempiń, Poland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Panek, M. Habitat Factors associated with the decline in brown hare abundance in Poland in the beginning of the 21st century. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 915–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamieniarz, R.; Voigt, U.; Panek, M.; Strauss, E.; Niewęgłowski, H. The effect of landscape structure on the distribution of brown hare Lepus europaeus in farmlands of Germany and Poland. Acta Theriol. 2013, 58, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santilli, F.; Viviano, A.; Mori, E. Dietary habits of the European brown hare: Summary of knowledge and management relapses. Ethol. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 36, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belova, O. Foraging Character of Deer Cervidae and Brown Hare Lepus europaeus on the Littoral Area of Pure Pine Forests in Lithuania. Balt. For. 2005, 11, 94–108. [Google Scholar]

- Beuković, M.; Đorđević, N.; Popović, Z.; Beuković, D.; Đorđević, M. Nutrition specificity of brown hare (Lepus europaeus) as a cause of the decreased number of population. Savrem. Poljopr. 2011, 60, 403–412. [Google Scholar]

- Tscharntke, T.; Batáry, P.; Grass, I. Mixing on- and off-field measures for biodiversity conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buglione, M.; De Filippo, G.; Conti, P.; Fulgione, D. Eating in an extreme environment: Diet of the European hare (Lepus europaeus) on Vesuvius. Eur. Zool. J. 2022, 89, 1201–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokos, C.; Andreadis, K.; Papageorgiou, N. Diet adaptability by a generalist herbivore: The case of brown hare in a Mediterranean agroecosystem. Zool. Stud. 2015, 54, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katona, K.; Altbacker, V. Diet estimation by faeces analysis: Sampling optimisation for the European hare. Folia Zool. 2002, 51, 11–16. [Google Scholar]

- Dalerum, F.; Angerbjörn, A. Resolving temporal variation in vertebrate diets using naturally occurring stable isotopes. Oecologia 2005, 44, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibowski, P.; Brzeziński, M.; Suska-Malawska, M.; Zub, K. Diet/hair and diet/faeces trophic discrimination factors for stable carbon and nitrogen isotopes, and hair regrowth in the yellow-necked mouse and bank vole. Ann. Zool. Fenn. 2022, 59, 171–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Pineda-Munoz, S. The temporal scale of diet and dietary proxies. Ecol. Evol. 2016, 6, 1883–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, G.; Danieli, P.P.; Primi, R.; Amici, A.; Lauteri, M. Stable isotopes in tissues discriminate the diet of free-living wild boar from different areas of central Italy. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Careddu, G.; Ciucci, P.; Mondovì, S.; Calizza, E.; Rossi, L.; Costantini, M.L. Gaining insight into the assimilated diet of small bear populations by stable isotope analysis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balčiauskas, L.; Balčiauskienė, L.; Garbaras, A.; Stirkė, V. Diversity and Diet Differences of Small Mammals in Commensal Habitats. Diversity 2021, 13, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva, N.; Hobson, K.A.; Zalewski, A.; Cortés-Avizanda, A.; Donázar, J.A. Mammal communities of primeval forests as sentinels of global change. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e17045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankevičiūtė, J.; Pėtelis, K.; Baranauskaitė, J.; Narauskaitė, G. Comparison of two age determination methods of the European Hares (Lepus europaeus Pallas, 1778) in southwest Lithuania. Acta Biol. Univ. Daugavp. 2011, 11, 22–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mihajlović, N.; Stepić, S.; Lavadinović, V.; Beuković, D.; Ignjatović, A.; Popović, Z. Improving the method of lens mass preparation for age assessment in the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus). Acta Zool. Acad. Sci. Hung. 2023, 69, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A.L.; Inger, R.; Parnell, A.C.; Bearhop, S. Comparing Isotopic Niche Widths among and within Communities: SIBER—Stable Isotope Bayesian Ellipses in R. J. Anim. Ecol. 2011, 80, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Game Animal Census. Available online: https://am.lrv.lt/lt/veiklos-sritys-1/gamtos-apsauga/medziokle/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Mayer, M.; Ullmann, W.; Sunde, P.; Fischer, C.; Blaum, N. Habitat selection by the European hare in arable landscapes: The importance of small-scale habitat structure for conservation. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 11619–11633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sliwinski, K.; Ronnenberg, K.; Jung, K.; Strauß, E.; Siebert, U. Habitat requirements of the European brown hare (Lepus europaeus Pallas 1778) in an intensively used agricultural region (Lower Saxony, Germany). BMC Ecol. 2019, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selimovic, A.; Tissier, M.L.; Arnold, W. Maize monoculture causes niacin deficiency in free-living European brown hares and impairs local population development. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2022, 10, 1017691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schai-Braun, S.C.; Reichlin, T.S.; Ruf, T.; Klansek, E.; Tataruch, F.; Arnold, W.; Hackländer, K. The European hare (Lepus europaeus): A picky herbivore searching for plant parts rich in fat. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, F.D.; Hackländer, K.; Arnold, W.; Ruf, T. Effects of season and reproductive state on lipid intake and fatty acid composition of gastrointestinal tract contents in the European hare. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2011, 181, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benda, R.; Zsolt, B. Autumn diet of European hare (Lepus europaeus) in the Naszály hills. Rev. Agric. Rural Dev. 2022, 11, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rödel, H.G.; Völkl, W.; Kilias, H. Winter browsing of brown hares: Evidence for diet breadth expansion. Mamm. Biol. 2004, 69, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schai-Braun, S.C.; Weber, D.; Hackländer, K. Spring and autumn habitat preferences of active European hares (Lepus europaeus) in an agricultural area with low hare density. Eur. J. Wildl. Res. 2013, 59, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, F.; Schai-Braun, S.; Weber, D.; Amrhein, V. European hares select resting places for providing cover. Hystrix 2011, 22, 291–299. [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski, K.; Nowakowski, J.J. Studies on the European hare. 49. Spatial distribution of brown hare Lepus europaeus populations in habitats of various types of agriculture. Acta Theriol. 1993, 38, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavliska, P.L.; Riegert, J.; Grill, S.; Šálek, M. The effect of landscape heterogeneity on population density and habitat preferences of the European hare (Lepus europaeus) in contrasting farmlands. Mamm. Biol. 2018, 88, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K.; Vaughan Jennings, N.; Harris, S. A quantitative analysis of the abundance and demography of European hares Lepus europaeus in relation to habitat type, intensity of agriculture and climate. Mammal Rev. 2005, 35, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, E.; Carbone, R.; Viviano, A.; Calosi, M.; Fattorini, N. Factors affecting spatiotemporal behaviour in the European brown hare Lepus europaeus: A meta-analysis. Mammal Rev. 2022, 52, 454–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristić, Z.; Ponjiger, I.; Matejević, M.; Kovačević, M.; Ristić, N.; Marković, V. Effects of factors associated with the decline of brown hare abundance in the Vojvodina region (Serbia). Hystrix 2021, 32, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schai-Braun, S.C.; Hackländer, K. Home range use by the European hare (Lepus europaeus) in a structurally diverse agricultural landscape analysed at a fine temporal scale. Acta Theriol. 2014, 59, 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujhegyi, N.; Keller, N.; Patkó, L.; Biró, Z.; Tóth, B.; Szemethy, L. Agri-environment schemes do not support Brown Hare populations due to inadequate scheme application. Acta Zool. Acad. Sci. Hung. 2021, 67, 263–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ševčík, R.; Krivopalova, A.; Cukor, J. Přímý vliv struktury zemědělské krajiny na výměru domovských okrsků zajíce polního: Předběžné výsledky z České republiky. Zpr. Lesn. Výzk. 2023, 68, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metcalfe, J.Z. C3 Plant Isotopic Variability in a Boreal Mixed Woodland: Implications for Bison and Other Herbivores. PeerJ 2021, 9, e12167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sponheimer, M.; Robinson, T.; Ayliffe, L.; Passey, B.; Roeder, B.; Shipley, L.; Lopez, E.; Cerling, T.; Dearing, D.; Ehleringer, J. An Experimental Study of Carbon-Isotope Fractionation between Diet, Hair, and Feces of Mammalian Herbivores. Can. J. Zool. 2003, 81, 871–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Year | Month | Sex | Age Class | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | Nov | Dec | Jan | M | F | I | II | III | IV | |

| Lithuania | 14 | 55 | 14 | – | 27 | 56 | 31 | 34 | 39 | 9 | 16 | 15 |

| Poland | 18 | 50 | 18 | 50 | – | n/a | n/a | 42 | 6 | 13 | 3 | |

| Country | n | Mean δ13C (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) | Mean δ15N (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithuania | 83 | −26.81 ± 1.01 | −28.61–−23.24 | 4.58 ± 1.14 | 2.30–9.80 |

| Poland | 68 | −25.74 ± 0.90 | −27.11–−20.60 | 4.68 ± 0.65 | 3.27–6.48 |

| Habitat | n | Mean δ13C (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) | Mean δ15N (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Field | 19 | −26.55 ± 0.86 | −27.92–−25.05 | 4.58 ± 0.96 | 3.25–6.22 |

| Forest | 27 | −26.57 ± 1.11 | −28.01–−23.24 | 4.70 ± 1.01 | 2.67–6.48 |

| Shrub | 17 | −27.16 ± 1.11 | −28.61–−24.73 | 4.50 ± 0.99 | 3.15–6.37 |

| Riverside | 6 | −27.33 ± 0.59 | −27.94–−26.47 | 3.68 ± 0.77 | 2.30–4.43 |

| Settlement | 1 | −28.58 | −28.58–−28.58 | 4.87 | 4.87–4.87 |

| Orchard | 68 | −25.74 ± 0.90 | −27.11–−20.60 | 4.68 ± 0.65 | 3.27–6.48 |

| Country | Year/Month | n | Mean δ13C (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) | Mean δ15N (‰) ± SD | Range (Min–Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithuania | 2023 | 14 | −26.92 ± 0.81 | −28.01–−25.30 | 4.05 ± 0.86 | 2.67–6.01 |

| 2024 | 55 | −26.86 ± 1.12 | −28.61–−23.24 | 4.75 ± 1.26 | 2.30–9.80 | |

| 2025 | 14 | −26.53 ± 0.70 | −27.36–−25.31 | 4.41 ± 0.67 | 3.42–5.67 | |

| Poland | 2023 | 18 | −26.36 ± 0.50 | −27.11–−25.30 | 5.08 ± 0.43 | 3.96–5.60 |

| 2024 | 50 | −25.51 ± 0.91 | −26.99–−20.60 | 4.53 ± 0.66 | 3.27–6.48 | |

| Lithuania | December | 27 | −26.69 ± 0.88 | −28.01–−25.05 | 4.40 ± 0.98 | 2.67–6.48 |

| January | 56 | −26.87 ± 1.07 | −28.61–−23.24 | 4.66 ± 1.21 | 2.30–9.80 | |

| Poland | November | 18 | −26.36 ± 0.50 | −27.11–−25.30 | 5.08 ± 0.43 | 3.96–5.60 |

| December | 50 | −25.51 ± 0.91 | −26.99–−20.60 | 4.53 ± 0.66 | 3.27–6.48 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Balčiauskas, L.; Vaitkevičiūtė-Koklevičienė, R.; Garbaras, A.; Stankevičiūtė, J.; Garbarienė, I.; Balčiauskienė, L. Stable Isotope Analysis Reveals Habitat-Driven Dietary Niches of Lepus europaeus. Animals 2026, 16, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010015

Balčiauskas L, Vaitkevičiūtė-Koklevičienė R, Garbaras A, Stankevičiūtė J, Garbarienė I, Balčiauskienė L. Stable Isotope Analysis Reveals Habitat-Driven Dietary Niches of Lepus europaeus. Animals. 2026; 16(1):15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010015

Chicago/Turabian StyleBalčiauskas, Linas, Rasa Vaitkevičiūtė-Koklevičienė, Andrius Garbaras, Jolanta Stankevičiūtė, Inga Garbarienė, and Laima Balčiauskienė. 2026. "Stable Isotope Analysis Reveals Habitat-Driven Dietary Niches of Lepus europaeus" Animals 16, no. 1: 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010015

APA StyleBalčiauskas, L., Vaitkevičiūtė-Koklevičienė, R., Garbaras, A., Stankevičiūtė, J., Garbarienė, I., & Balčiauskienė, L. (2026). Stable Isotope Analysis Reveals Habitat-Driven Dietary Niches of Lepus europaeus. Animals, 16(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010015