Breed-Dependent Divergence in Breast Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Between White King and Tarim Pigeons

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

2.2. Slaughter and Sample Collection

2.3. Lipidomic Analysis

2.3.1. Metabolite Extraction

2.3.2. UPLC-MS/MS Conditions

2.3.3. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.3.4. Quality Control (QC) Strategy

2.4. Enzyme Activity and Muscle Glycogen Measurements

2.5. Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

3. Results

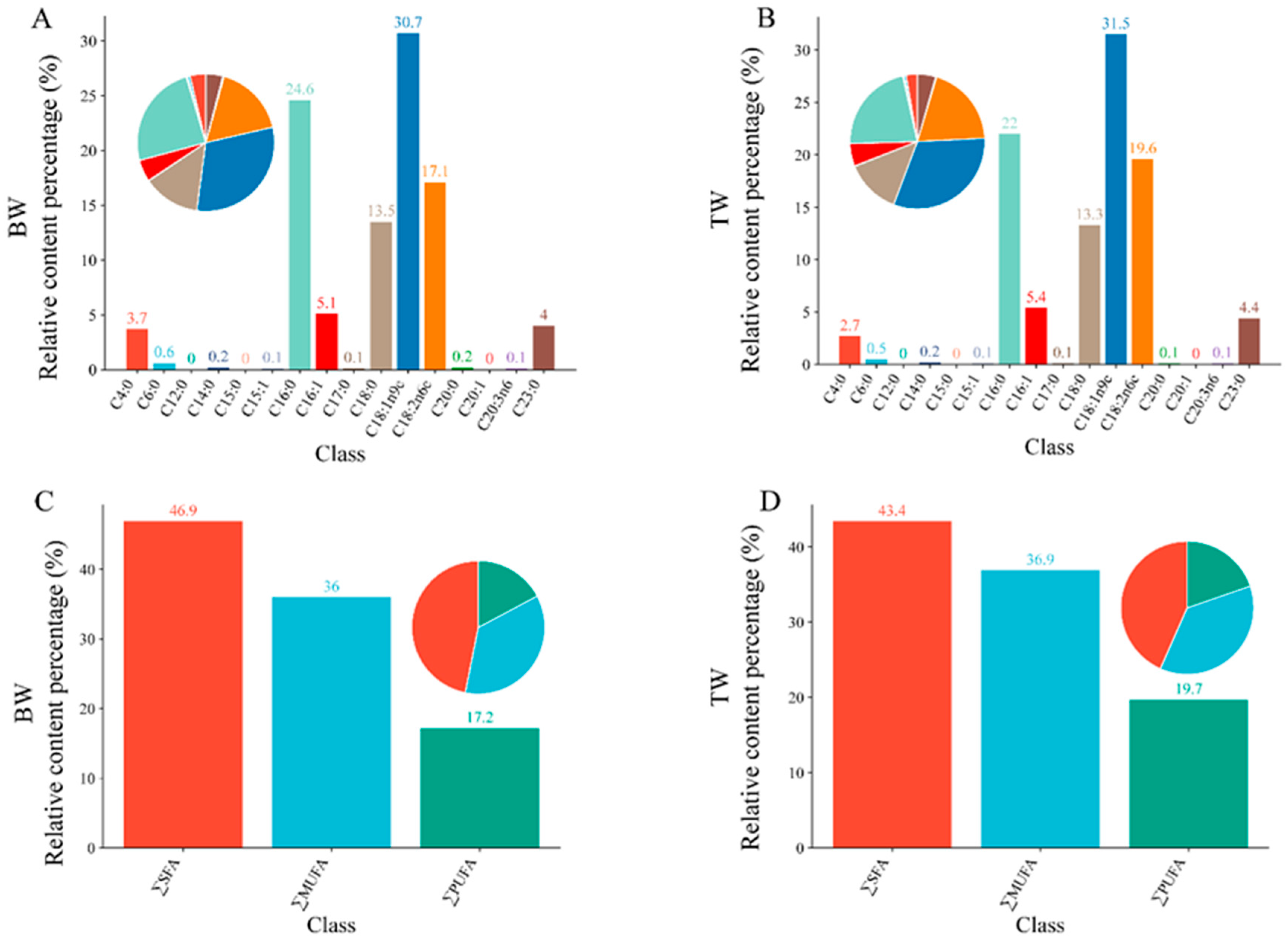

3.1. Comparison of Fatty Acid Composition Between BW and TM Pigeons

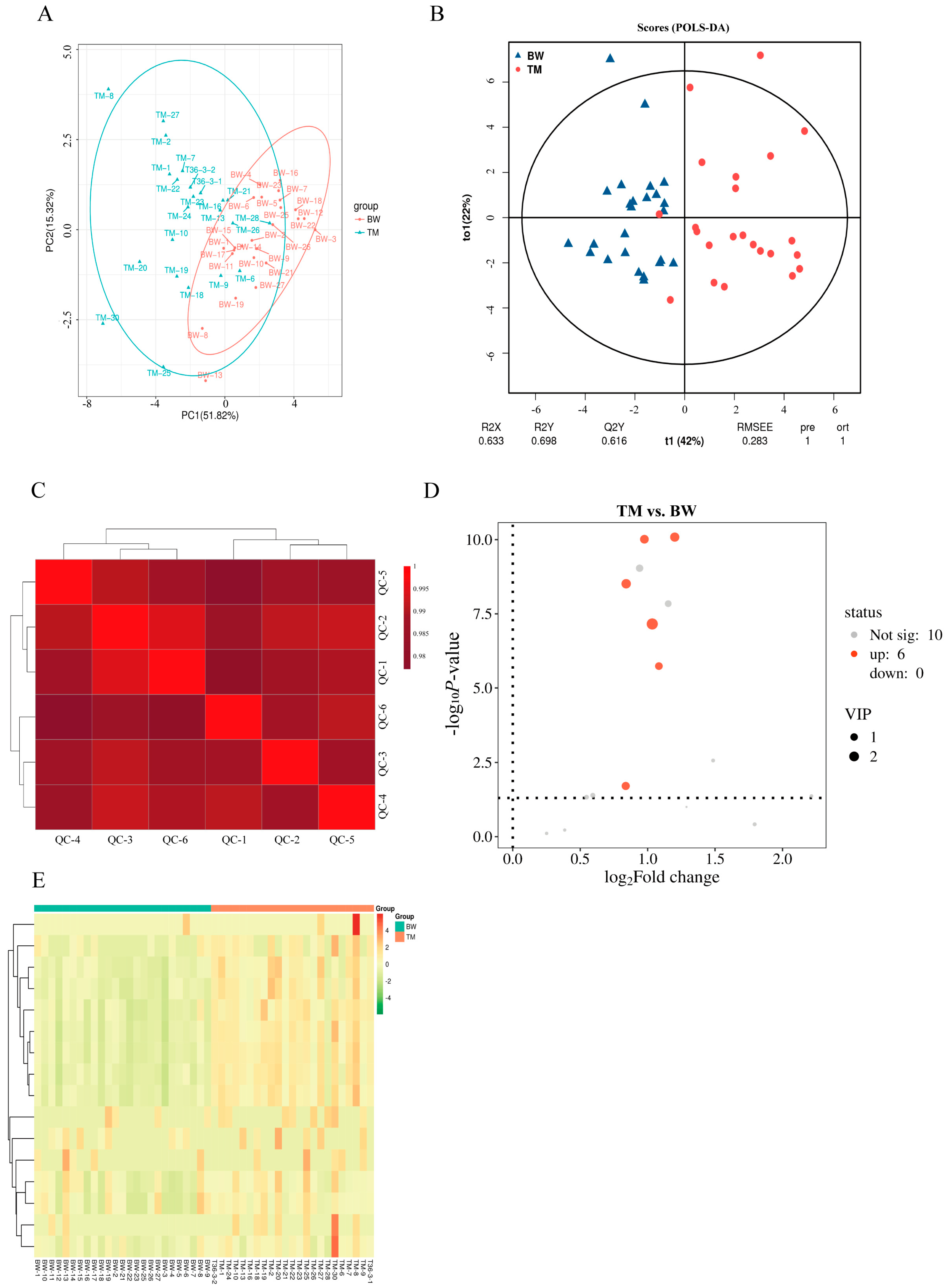

3.2. Comparative Fatty Acid Profiling Between BW and TM Pigeons

3.3. Breed-Dependent Differences in Fatty Acid Composition

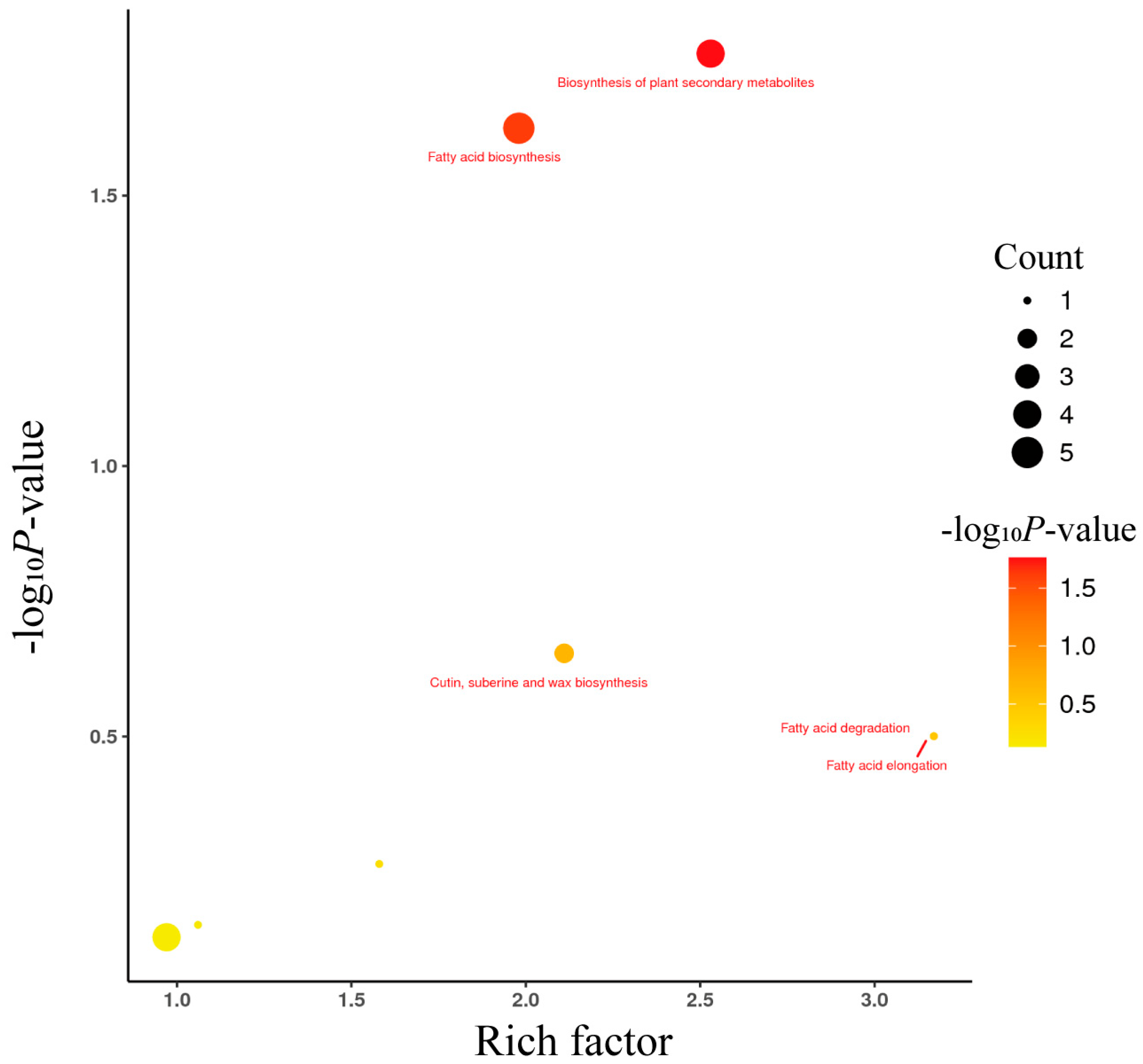

3.4. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway Enrichment Analysis of Differential Lipid Metabolites

3.5. Comparison of Muscle Metabolic Enzyme Activities Between BW and TM Pigeons

4. Discussion

4.1. Breed-Associated Differences in Fatty Acid Composition

4.2. Key Fatty Acids and Potential Physiological Relevance

4.3. Muscle Metabolic Enzyme Activities and Glycogen Content

4.4. Implications for Pigeon Breeding, Local Breed Conservation, and Future Research

4.5. Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ji, F.; Zhang, D.Y.; Shao, Y.X.; Yu, X.; Liu, X.; Shan, D.; Wang, Z. Changes in the diversity and composition of gut microbiota in pigeon squabs infected with Trichomonas gallinae. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brzoska, F. Squabs-fattened slaughter pigeons are exclusive poultry, part I. Pol. Poult. 2019, 3, 77–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, H.M.; Zi, C.; Gu, J.; Wang, Z.Y. The mediation of pigeon egg production by regulating the steroid hormone biosynthesis of pigeon ovarian granulosa cells. Poult. Sci. 2020, 99, 6075–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.G.; Pan, N.X.; Chen, M.J.; Wang, X.Q.; Yan, H.C.; Gao, C.Q. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with dl-Methionine and dl-Methionyl-dl-Methionine in Breeding Pigeons on the Carcass Characteristics, Meat Quality and Antioxidant Activity of Squabs. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.P.; Pu, Z.; Mu, C.Y.; Chang, L.L.; Fu, S.Y.; Zhang, R. The status and introduction of China’s meat pigeon breeding genetic resources. Chin. Livest. Poult. Breed. Ind. 2018, 14, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, L.L.; Tang, Q.P.; Zhang, R.; Fu, S.Y.; Mu, C.Y.; Shen, X.Y.; Bu, Z. Evaluation of meat quality of local pigeon varieties in china. Animals 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.H.; Zhou, H.; Huang, J.L.; Zhu, W.Q.; Hou, H.B.; Li, H.J.; Zhao, L.L.; Zhang, J.; Liu, J.J.; Qin, C. Near telomere-to-telomere assembly of the Tarim pigeon (Columba livia) genome. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Committee for Genetic Resources of Livestock and Poultry. Chinese Livestock and Poultry Genetic Resources: Poultry Volume; Agricultural Press of China: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lan, L.B.; Wei, B.N.; Xu, H.Z.; Su, Z.Q.; Wang, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z.P.; Chen, Y.T.; Huang, Y.M.; Zhang, X.X. Suggestions for the conservation and utilization of the pigeon germplasm resources of the Tarim region. Chin. Livest. Poult. Breed. Ind. 2024, 9, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Ma, J.Y.; Shen, L.; Li, Y.P.; Xie, S.X.; Li, H.X.; Li, J.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, Z. Genomic insights into pigeon breeding: GWAS for economic traits and the development of a high-throughput liquid phase array chip. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 104872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, J.D.; Richardson, R.I.; Nute, G.R.; Fisher, A.V.; Campo, M.M.; Kasapidou, E.; Sheard, P.R.; Enser, M. Effects of fatty acids on meat quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2004, 66, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.I.; Jo, C.; Tariq, M.R. Meat flavor precursors and factors influencing flavor precursors—A systematic review. Meat Sci. 2015, 110, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupsaite, D.; Buckiuniene, V.; Bliznikas, S.; Sidlauskiene, S.; Dauksiene, A.; Klementaviciute, J.; Jurkevicius, A.; Zaborskiene, G.; Bartkiene, E. Impact of Romanov breed lamb gender on carcass traits and meat quality parameters including biogenic amines and malondialdehyde changes during storage. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 11, 1745–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.P.; Fan, W.L.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.B.; Xu, Y.X.; Hu, J.; Liu, T.F.; Yu, S.M.; Zhang, H.; Tang, J.; et al. Metabolome genome-wide association analyses identify a splice mutation in AADAT affects lysine degradation in duck skeletal muscle. Sci. China Life Sci. 2025, 68, 2094–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smink, W.; Gerrits, W.J.; Hovenier, R.; Geelen, M.J.; Verstegen, M.W.; Beynen, A.C. Effect of dietary fat sources on fatty acid deposition and lipid metabolism in broiler chickens. Poult. Sci. 2010, 89, 2432–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skřivan, M.; Marounek, M.; Englmaierová, M.; Čermák, L.; Vlčková, J.; Skřivanová, E. Effect of dietary fat type on intestinal digestibility of fatty acids, fatty acid profiles of breast meat and abdominal fat, and mRNA expression of lipid-related genes in broiler chickens. PLoS ONE 2018, 19, e0196035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosotani, M.; Kametani, K.; Ohno, N.; Hiramatsu, K.; Kawasaki, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Iwasaki, T.; Watanabe, T. The unique physiological features of the broiler pectoralis major muscle as suggested by the three-dimensional ultrastructural study of mitochondria in type IIb muscle fibers. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2021, 83, 1764–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Xu, F.; Liu, Y. Research progress on regulating factors of muscle fiber heterogeneity in poultry: A review. Poult. Sci. 2024, 103, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.V.; Hausman, G.J.; Guan, L.; Du, M.; Rasmussen, T.P.; Poulos, S.P.; Mir, P.; Bergen, W.G.; Fernyhough, M.E.; McFarland, D.C.; et al. Lipid metabolism, adipocyte depot physiology and utilization of meat animals as experimental models for metabolic research. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2010, 22, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; He, X.F.; Ma, B.B.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, G.H.; Gao, F. Increased fat synthesis and limited apolipoprotein B cause lipid accumulation in the liver of broiler chickens exposed to chronic heat stress. Poult. Sci. 2019, 98, 3695–3704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbarian, A.; Michiels, J.; Degroote, J.; Majdeddin, M.; Golian, A.; De Smet, S. Association between heat stress and oxidative stress in poultry; mitochondrial dysfunction and dietary interventions with phytochemicals. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 28, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jump, D.B. Fatty acid regulation of hepatic lipid metabolism. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. Metab. Care 2011, 14, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Y.; Gao, P.; Xie, K. Effects of dietary Acremonium terricola culture supplementation on the quality, conventional characteristics, and flavor substances of Hortobágy goose meat. J. Anim. Sci. Technol. 2022, 64, 950–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, J.D.; Enser, M.; Fisher, A.V.; Nute, G.R.; Sheard, P.R.; Richardson, R.I.; Hughes, S.I.; Whittington, F.M. Fat deposition, fatty acid composition and meat quality: A review. Meat Sci. 2008, 78, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muir, W.M.; Wong, G.K.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Groenen, M.A.; Crooijmans, R.P.; Megens, H.J.; Zhang, H.; Okimoto, R.; Vereijken, A.; et al. Genome-wide assessment of worldwide chicken SNP genetic diversity indicates significant absence of rare alleles in commercial breeds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 17312–17317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.H.; Keightley, P.D. Understanding quantitative genetic variation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002, 3, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X.G.; Gao, L.B.; Zhang, H.J.; Wang, J.; Qiu, K.; Qi, G.H.; Wu, S.G. Discriminating eggs from two local breeds based on fatty acid profile and flavor characteristics combined with classification algorithms. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2021, 41, 936–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, D.; Dimovska, N.; Hajrulai-Musliu, Z.; Teodorović, V.; Nikolić, A.; Karabasil, N.; Dimitrijević, M.; Mirilović, M. Fatty acid profile as a discriminatory tool for the origin of lamb muscle and adipose tissue from different pastoral grazing areas in North Macedonia—A short communication. Meat Sci. 2020, 162, 108020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Bin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Cui, L.; Ma, J.; Chen, C.; Ai, H.; Xiao, S.; Ren, J.; Huang, L. Genome-wide association studies for fatty acid metabolic traits in five divergent pig populations. Sci. Rep. 2016, 21, 24718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Y.; Gu, J.; Li, H.; Wu, R.; Jia, J.; Shen, J.; Li, W.; Han, R.; Sun, G.; et al. Multi-Omics profiling of lipid variation and regulatory mechanisms in poultry breast muscles. Animals 2025, 15, 694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Abbreviation | BW | TM | Fold Change | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid | C4:0 | 5.15 | 7.53 | 1.46 | 0.0468 |

| Hexanoic acid | C6:0 | 0.865 | 1.31 | 1.51 | 0.0407 |

| Lauric acid | C12:0 | 0.0188 | 0.0458 | 2.44 | 0.0996 |

| Myristic acid | C14:0 | 0.326 | 0.626 | 1.92 | 9.19 × 10−10 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | C15:0 | 0.0124 | 0.0575 | 4.64 | 0.0425 |

| cis-10-Pentadecenoic acid | C15:1 | 0.154 | 0.183 | 1.19 | 0.777 |

| Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 34.0 | 60.8 | 1.79 | 3.07 × 10−9 |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16:1 | 7.04 | 14.9 | 2.12 | 1.83 × 10−6 |

| Heptadecanoic acid | C17:0 | 0.0940 | 0.263 | 2.80 | 0.00272 |

| Stearic acid | C18:0 | 18.6 | 36.6 | 1.97 | 9.71 × 10−11 |

| Oleic acid | C18:1n9c | 42.5 | 87.0 | 2.05 | 6.95 × 10−8 |

| Linoleic acid | C18:2n6c | 23.6 | 54.2 | 2.30 | 8.23 × 10−11 |

| Arachidic acid | C20:0 | 0.213 | 0.381 | 1.79 | 0.0196 |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid | C20:1 | 0.0157 | 0.0545 | 3.47 | 0.384 |

| cis-8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | C20:3n6 | 0.163 | 0.213 | 1.31 | 0.599 |

| Tricosanoic acid | C23:0 | 5.46 | 12.1 | 2.22 | 1.44 × 10−8 |

| ∑SFA | 64.7 | 120 | 1.85 | <0.001 | |

| ∑MUFA | 49.7 | 102 | 2.06 | <0.001 | |

| ∑PUFA | 23.7 | 54.4 | 2.29 | <0.001 | |

| ∑MUFA/∑SFA | 0.783 | 0.846 | 1.08 | 0.257 | |

| ∑PUFA/∑MUFA | 0.494 | 0.553 | 1.12 | 0.170 |

| Name | Abbreviation | VIP Score |

|---|---|---|

| Butyric acid | C4:0 | 0.235 |

| Hexanoic acid | C6:0 | 0.284 |

| Lauric acid | C12:0 | 0.0151 |

| Myristic acid | C14:0 | 0.962 |

| Pentadecanoic acid | C15:0 | 0.0857 |

| cis-10-Pentadecenoic acid | C15:1 | 0.0661 |

| Palmitic acid | C16:0 | 1.85 |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16:1 | 1.07 |

| Heptadecanoic acid | C17:0 | 0.115 |

| Stearic acid | C18:0 | 1.51 |

| Oleic acid | C18:1n9c | 2.81 |

| Linoleic acid | C18:2n6c | 1.75 |

| Arachidic acid | C20:0 | 1.26 |

| 11-Eicosenoic acid | C20:1 | 0.127 |

| cis-8,11,14-Eicosatrienoic acid | C20:3n6 | 0.0599 |

| Tricosanoic acid | C23:0 | 0.741 |

| Item | BW | TM | SEM | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CPT1 (nmol/min·mgprot) | 3.60 b | 9.37 a | 0.872 | <0.001 |

| Muscle glycogen (mg/g) | 0.185 b | 0.225 a | 0.0062 | <0.001 |

| CS (U/mgprot) | 2.94 b | 17.9 a | 2.28 | <0.001 |

| LDH (U/gprot) | 12.8 a | 6.70 b | 0.955 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, B.; Liu, J.; Wei, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, W.; Kishawy, A.T.Y.; Shen, L.; Ma, J.; Li, Y.; Xie, S.; et al. Breed-Dependent Divergence in Breast Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Between White King and Tarim Pigeons. Animals 2026, 16, 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010144

Zhang B, Liu J, Wei H, Liu L, Zhang W, Kishawy ATY, Shen L, Ma J, Li Y, Xie S, et al. Breed-Dependent Divergence in Breast Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Between White King and Tarim Pigeons. Animals. 2026; 16(1):144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Bo, Jiajia Liu, Hua Wei, Li Liu, Wanchao Zhang, Asmaa Taha Yaseen Kishawy, Li Shen, Jianyuan Ma, Yipu Li, Shuxian Xie, and et al. 2026. "Breed-Dependent Divergence in Breast Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Between White King and Tarim Pigeons" Animals 16, no. 1: 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010144

APA StyleZhang, B., Liu, J., Wei, H., Liu, L., Zhang, W., Kishawy, A. T. Y., Shen, L., Ma, J., Li, Y., Xie, S., Li, H., Li, J., & Wang, Z. (2026). Breed-Dependent Divergence in Breast Muscle Fatty Acid Composition Between White King and Tarim Pigeons. Animals, 16(1), 144. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani16010144